#also wait did he cite.. elvis… as one of the greats? hey wait who did he get his inspo from again? 🤔

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

cant experience the full spectrum of emotions that is my 60s-70s escapism bc my shitty victrola vinyl player doesn’t work anymore >:(

I’m using the right cord and the power won’t turn on so I know it’s a hardware issue and I’ll have to send it in for repairs

#also guy at best buy rambled to my bf and i about better vinyl players to invest in#and also preached abt 50s music having the Bigger Better artists and how old music is so unappreciated n im like#amen brother i get that but im still pissed about my vinyl player breaking when i haven’t used it in literal years#also wait did he cite.. elvis… as one of the greats? hey wait who did he get his inspo from again? 🤔

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reading, Writing & Real Life

Sometimes I get asked who or what influenced me most in my deep-seated (and very early) desire to write.

I’ve named books and writers: Tristram Shandy (don’t miss the book, but don’t miss the movie either), Norse mythology, and Henry Green, Alice Munro, Grace Paley and Hubert Selby Jr., Ralph Ellison, Italo Svevo, Sigrid Undset and Zora Neale Hurston. For the last few years I’ve been working on a series of loosely connected short stories suggested by Dawn Powell’s novel My Home Is Far Away, a book that I can best describe as suggesting the tone of Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander transplanted to the world of Winesburg, Ohio. Which could lead me to Hemingway, or Hemingway’s Boat, or – well, I’m sure you get the point.

There were teachers, certainly. Omar Pound (Omar Shakespear Pound, son of Ezra) is the one who stands out the most. He came to Roxbury Latin when I was in the ninth grade and was greeted with almost universal rejection bordering on scorn by my classmates – for his oddity, for his self-determined eccentricities, for his stubborn scruffiness, both personal and intellectual. But for me, and a few others, he provided a wonderful opportunity for self-expression in the two or three extended writing exercises he assigned each week, suggested by a phrase or saying that he provided, of which the only one that comes immediately to mind is, “Only a fool learns from experience.” True? Untrue? I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now. But as I recall, I wrote a short story that I hope was as open-ended in a fifteen-year-old way and lent itself as much to individual interpretation as I have intended in my biographies of Elvis, Sam Cooke, and Sam Phillips, or any of the other books that I’ve written.

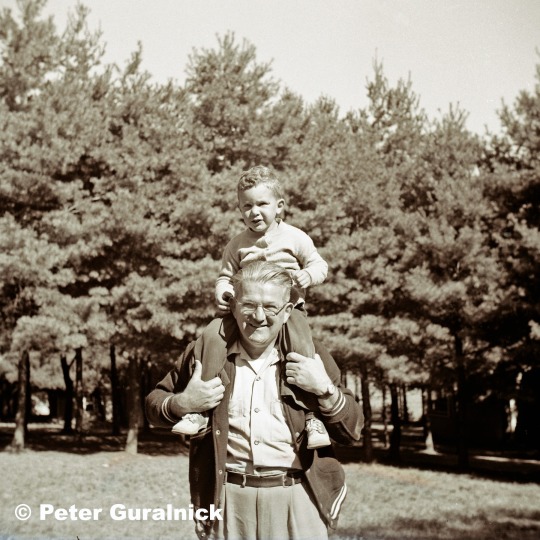

But there’s still that lingering question: what in the world would lead an eight or nine-year-old kid to want to be a writer – if he couldn’t be a be a Major League baseball player, that is. It was my grandfather, Philip Marson, who taught English for over thirty years at Boston Latin (no, not the same Latin School – it’s complicated), founded and ran Camp Alton (which I would later run) in what he conceived of as a fresh-air expansion of the educational experience, dreamed of having the time one day to finish Finnegans Wake (he finally did at seventy-eight, over his customary breakfast of shredded wheat), and explored the second-hand bookstores of Boston’s Cornhill for $.25 masterpieces like Jean Toomer’s Cane, without necessarily passing up a sidetrip to the Old Howard burlesque show in adjacent Scollay Square, where he pulled his hat down over his face for fear of running into one of his students. I wasn’t around for the Old Howard, which closed in 1953, but by the time I was ten or eleven I started accompanying him on his foraging trips to Cornhill (now the site of Government Center), which always included a mid-morning hot fudge sundae at Bailey’s, where the fudge sauce was so thick it could have been a meal by itself.

It was his enthusiasm, I think, that inspired me most of all, his enthusiasm and his unfettered appreciation for life, literature, sports (he was a three-sport athlete at Tufts – Tris Speaker, the Grey Eagle, he said, had praised him for his play in a college game at Fenway Park), grammatical niceties, and democratic ideals. More than just appreciation, it was his undisguised avidity for experience and people of every sort. “Hey, Pete,” he would shout out in his high-pitched voice, to my pre-adolescent, adolescent, and post-adolescent (does that count as adult?) embarrassment, “Will you look at that?” And I’m not going to tell you what that was – because it’s still embarrassing. But, you know, it was always interesting.

But none of that would have counted for anywhere near as much if he were not such an unrestrained fan of me – it just seemed like whatever I did was all right with him. He came to all my baseball games, naturally, but when I took up tennis, which he had always scorned as an artificially encumbered (don’t ask me why), pointless kind of sport, he embraced it wholeheartedly, coming to all my tournaments and swiftly learning the finer points of the game. If I recommended a book, he was quick to embrace it. And when at the age of eleven and twelve and into early adolescence, I suffered from fears that so crippled me that I found it difficult even to go to school, his belief in me never wavered. Or more to the point perhaps, he never seemed to see me as any less, or any different, a person.

I grew up in my grandparents’ house off and on from the time I was born. My father, whom I could cite as an equally inspiring influence in terms of both character and commitment, landed in England the day I was born and didn’t return from the War until I was more than two years old, nearly a year after V-E Day. So my mother and I camped out with my grandparents, very comfortably for me, though I’m not so sure about my mother. (One of the short stories I’ve written lately tries to imagine what it must have been like for her, twenty-three, twenty-four-years old, with no certainty of the future, an only child living with her only child in her parents’ house.) Then, when my father finally came home, we remained for another three years, until we could finally afford a place of our own, moving into the garden apartments that had recently opened up near-by as affordable housing for returning veterans. A year or two after that, my grandparents gave my parents the house and moved to a roomy old apartment in Coolidge Corner, not far away.

Staying with my grandparents on weekends in their new apartment, even more book-crammed than the house because it was crammed with the same books, was always a treat. We went to theater together, my grandmother, my grandfather, and I – I can remember seeing Charles Laughton in Don Juan in Hell, the stand-alone third act of George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman when I was nine or ten years old. (Shaw was always a great favorite of my grandfather’s, along with such native-born contrarians as H.L. Mencken.) We went to serious plays, musicals, Broadway try-outs, and revivals. Along with Shaw, Eugene O’Neill undoubtedly loomed largest in my grandfather’s theatrical cosmos, and it was as exciting to listen to my grandparents talk about seeing Paul Robeson make his Broadway debut in The Emperor Jones or attending O’Neill’s marathon nine-act Strange Interlude, which included a break for dinner, as it was to hear my grandfather tell the story of how he lost his hat when he stood up to cheer Franklin Roosevelt at the Boston Garden.

But it was books in the end that were the instigators of the most passionate discussions, books that inspired me to want to write books of my own, books that would always provide an impetus for dinner-time conversation and home décor. My grandfather introduced me to Romain Rolland’s Jean Christophe, to James Joyce and Knut Hamsun, Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford (he loved to discourse on what he called the shuttle-and-weave of their narrative technique), and Sigrid Undset. I’ll admit, I might well have been better off if I had stuck a little longer with the Landmark series of biographies that continued to excite me or the Scribner Classics editions of Jules Verne and Robert Louis Stevenson and James Fenimore Cooper, with those wonderful N.C. Wyeth illustrations, or any of the other children’s classics that I had indiscriminately devoured. But I was so bereft of self-awareness (while at the same time so consumed by self-consciousness) that I started to record my impressions of each of the books that I read in little tablet notebooks, earnest summaries not just of the books but of my own judgments of them. I could only express my “wonderment at, and admiration for, the author’s scope and ability,” I declared, writing about Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter when I was fifteen. And struggled for six handwritten pages to express more specifically my admiration for this 1000-page trilogy that takes place in fourteenth-century Norway, with its rare combination of epic sweep and unexpected intimacy. My grandfather considered it the greatest novel ever written, a judgment with which, as you can see, I struggled mightily to concur – and in fact still do. But I also knew, as my grandfather’s own omnivorous passion for discovery suggested, that all such judgments were nonsense. In the end, like the question of who was the greatest baseball player of all time, an early and abiding conversation of ours, it was a provisional title only, waiting for the next great thing to come along.

And yet, and yet, well, you know, when it comes right down to it, it wasn’t books or writing or epistemological fervor that were my primary inspiration. They would have meant nothing if it hadn’t been for everything else. What my grandfather communicated to me most of all was a hunger for life, for the raw stuff of life that served as the underpinning for every great book that either of us admired. I’m oversimplifying, I know, but it just seemed like, in the greater scheme of things, with my grandfather there was no exclusionary gene. There was no sense of high and low (no one appreciated a “dirty joke” more shamelessly than he) and, save for the inviolable principles of grammar and the strict standards of a “good education,” everything was in play, everything existed on the same human plane.

In many ways, I think that was what opened me up to the blues – not just the music but the experience of the music, the many different implications of the music – which turned out to be the single greatest revelation of my life. So many of the places where I started out are still the places where I am. Books, writing, playing sports (sadly, no more baseball), the blues. As my grandfather got older, his enthusiasm never diminished. When $100 Misunderstanding, an alternating dialogue between a fourteen-year-old black prostitute and her clueless white college john, came out in 1962, my grandfather got the idea that he and I could write a novel in the same manner about the generation gap, which was very much in the news then. We would write alternate chapters – well, you get the picture – and he was so excited about the idea that I couldn’t say no, though we never advanced to the point where we put anything down on paper. When the draft briefly threatened, he decided he would buy land in Canada and we could start a commune there, and while the threat went away before he was ever able to put his idea into practice, I had no doubt it would have been a very interesting (and well-ordered) commune.

A few years later, in 1970, he asked if I would help him run camp the following year. I’m not sure I need to explain, but this came like a bolt out of the blue. Alexandra and I had been working at camp for the last few years, and I was running the tennis program and coaching baseball. “No speculation,” I told my twelve-year-old charges, taking my cue, as always, from William Carlos Williams. It was a wonderful way to spend the summer, and it was certainly rewarding from any number of points of view, not least of which was being close to my grandparents. But not for one moment had the thought of running camp crossed my mind. I was twenty-six-years-old, working on my first full-length published book, Feel Like Going Home, and my fifth unpublished novel, Mister Downchild, and I thought I knew where my future lay.

At the same time, the idea of turning my grandfather down never crossed my mind. He was seventy-eight years old and had never asked for my help before – in fact, I couldn’t remember him ever asking anybody’s help. So, sure, yes, unequivocally. And yet I found it impossible to imagine how this could ever work. How exactly was I going to help? And if his idea was to defer to me, to withdraw and leave the day-to-day running of camp to me, well, this would require a lot more conviction, self-belief, and, above all, knowledge (since no one knew anything about the running of camp except for him) than I possessed. The question was, did I have it in me to be the person that I needed, that I wanted, for my grandfather’s sake, to be?

As it turned out, I never had to answer that question. My grandfather got sick – it appeared at first to be a stroke, it turned out to be a brain tumor – almost immediately after asking for my help. I kept things going over the winter in hopes that he would recover, and when he didn’t, it was like being thrown into the water and discovering, much to your surprise, that you actually knew how to swim. I ended up running camp by myself that summer, and I ran it for twenty-one years after that, and whatever my grandfather intended (and I suspect it was a great deal more than just providing me with an income to support my writing), it turned out to be one of the most rewarding, existentially engaging experiences of my life. And not just in the ways you might expect – camp was a thriving, self-sustaining community of 300 people that continued to grow and evolve, as did my own views of democratic institutions and possibilities – but because it inescapably exposed me to real life, it forced me out into a world in which my feelings were not the center of everything. A world of building things and balancing books, where you dealt of necessity (and to your own incalculable experiential benefit) with all kinds of different people, benefited from the wisdom and experience of others (could that have been what Omar Pound meant?), and learned not just to stand up for yourself but for everyone else, because no matter how much inner turmoil you might feel (and I think back to my ten- and –eleven-year-old self, curled up in a ball reading a book, afraid to leave the comforting familiarity of my room), you don’t have the luxury of dwelling on your own emotions. Because – why? Everyone is depending on you. It forced me, in other words, to grow up, in a way that deeply affected not only my writing but my ability to understand all the different personalities and perspectives that I wanted to portray in both my fiction and my nonfiction, in my biographies and profiles of such multifarious personalities as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Waylon Jennings, Sam Phillips, and Solomon Burke. It forced me, when it came right down to it, to embrace the world.

My grandfather used to come see me in my dreams sometimes. He always wore his tan windbreaker and stood by the tree on the right field line at camp, where he used to watch my games, both as a kid and as an adult. It was always good to see him – there was never a time I didn’t wish he would stay longer. But even though I rarely see him nowadays, I carry with me always the conviction that he communicated so unhesitantly: that everything is just out there waiting to be discovered. And I try to keep that belief in the forefront – well, maybe the backfront – of my mind. I continue to be drawn on by the prospect, I continue to struggle for its discovery.

3 notes

·

View notes