#also the comedy relief (bee) playing the straight man is always fun

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

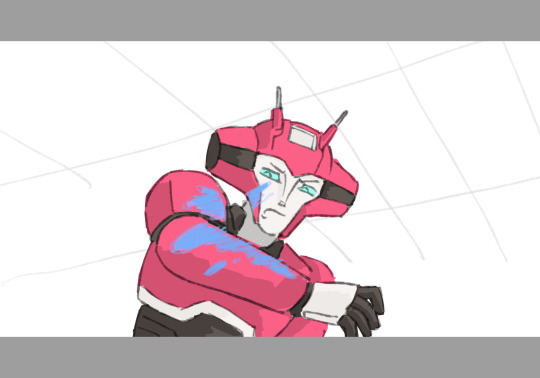

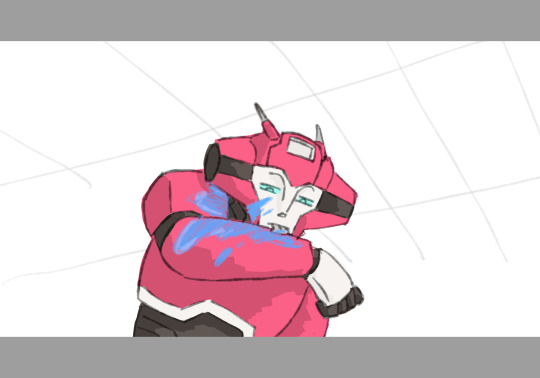

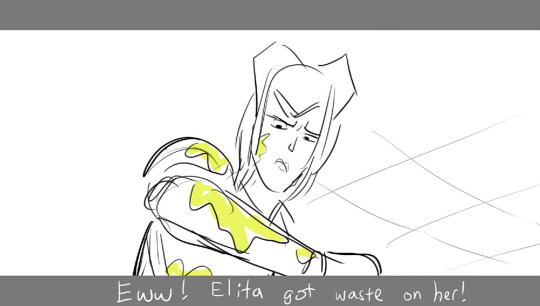

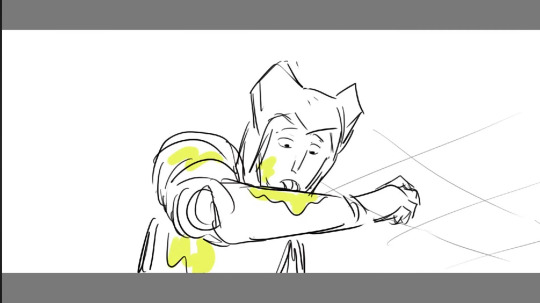

saw the new animatics n this was just so funny to me. i need more of elita being weird

original animatic frames:

#WAITER!!! more weirdo elita please#also the comedy relief (bee) playing the straight man is always fun#like ok clearly youre out of line if even the silly guy goes WHAT#transformers#transformers one#tf one#elita one#elita#bumblebee#b 127#my art

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephen Colbert Caps Comeback Year Hosting Emmys: "I Just Wanted to Do Jokes" (Q&A)

http://styleveryday.com/2017/09/11/stephen-colbert-caps-comeback-year-hosting-emmys-i-just-wanted-to-do-jokes-qa/

Stephen Colbert Caps Comeback Year Hosting Emmys: "I Just Wanted to Do Jokes" (Q&A)

The CBS host on his start in comedy, how Bill O’Reilly inspired his ‘Colbert Report’ character, David Letterman’s gracious handoff of ‘The Late Show’ and its comeback from a year-one fizzle: “I’ve allowed myself to become a pure performer.”

Just under two years ago, Stephen Colbert debuted as host of CBS’ The Late Show. And it hasn’t even been a year since sluggish ratings, an Emmys snub and a lack of buzz prompted some to begin writing off the onetime Comedy Central star whose Colbert Report had previously picked up two Emmys for variety series. His Late Show was so challenged that there even were whispers he’d be asked to swap time slots with James Corden.

What a difference a year — and a presidential election — can make. The Late Show (not NBC’s The Tonight Show) finished the season atop the late-night ratings for the first time in 22 years; The Late Show (not The Tonight Show) earned a series nom; and Colbert (not Corden) is set to host the Sept. 17 Emmy Awards, where The Late Show is also nominated for directing and writing (though both his series and Showtime election night special fell to the likes of Corden and Samantha Bee at the Creative Arts Emmys over the weekend).

In a wide-ranging August interview, Colbert kept his telecast plans close to the vest. But he spoke frankly about how he discovered comedy, the path that led him to Comedy Central’s The Daily Show and Colbert Report (led by a character modeled on Bill O’Reilly, “a well-intentioned, poorly-informed, high-status idiot”), that rocky first year on The Late Show (“I lost my mind!”) and the joy of becoming “pure performer.”

Below is an edited version of that conversation, which you can hear in full here.

You grew up in a large, observant Catholic family. How do you think you were shaped by that?

What is the role of religion in the life of the Colbert family? Where to begin? What is the role of marble in the shape of a statue? It was so important. On a certain pedestrian level, we went to church every Sunday, but we also said our prayers. Prayers every night. Prayers all the time. Offering it up to God, if there was something wrong, if you had some trouble. Well, Mom would say, “Offer it up. Offer it up. Whatever you’re suffering through right now.” She would say, “There’s another jewel in your crown, when you get to heaven.” Because we all have crowns when we get to heaven. We’d all say, “Oh, come on, that crown’s going to be so heavy when I get up there!” My mom made Halloween costumes of the saints, whatever your saint is — like Saint Stephen would wear rags and carry a stone because he was stoned to death. It was sort of infused in every aspect of our lives. My father was an intellectual. A real one, I believe. His idea of fun was reading French humanist philosophers, like Jacques Maritain. Christian Humanists. Faith was just enormous. My father and two of my brothers died when I was younger, and that brought home the needs of the faith. The faith served my mother and myself and my family in a profound way, because you’re faced with this enormous suffering.

How do you think you were changed by that tragedy?

I have said to myself more than once, “Gosh, I hope I live long enough to figure out what that did to me.” It’s almost like that event created a labyrinth in my mind, in which I could hide when I was younger. No one could find me if I went into the labyrinth of that experience, but I was also lost in there. Comedy was a relief. Every night for years, I played either George Carlin’s Class Clown or Bill Cosby’s Very Funny Fellow or Bill Cosby’s Wonderfulness or David Frye’s Richard Nixon: A Fantasy, Steve Martin’s Wild and Crazy Guy, Let’s Get Small… Comedy albums were the greatest drug. Religion is the opiate of the masses? Religion’s got nothing on comedy in terms of its opiate abilities. Comedy was my opiate. Comedy became… not my religion, but certainly, I heard a vocation there, like I wanted to be part of that. I wanted, in a way, without consciously knowing it, I wanted to be the person who made everybody feel better, and I saw comedy as a way to do it.

You started doing comedy professionally as part of Chicago’s Second City and later on the sketch show Exit 57, then The Dana Carvey Show, then a stint on Good Morning America, of all places. How did that happen — and how did that lead you to The Daily Show?

Somebody from ABC calls me and says “Hey, somebody from Good Morning America is going from the entertainment division to the news division,” because GMA had been entertainment. They said, “As we were metaphorically sort of handing over the keys, before we locked the door between the two divisions, somebody from news said, ‘Hey, is there anybody in entertainment who kind of looks straight, but could probably look like a reporter that we send out to do comedy pieces?’ And somebody said, ‘Stephen Colbert!’” I went over there, and they didn’t want me to be funny. They didn’t really want me to be funny. I did two pieces, and then they shot down 25 pitches in a row. But they had to pay me, so I was very grateful, because I could make rent.

While I was doing that, I got a call from my agent saying, “Do you want to go meet with The Daily Show? People are looking for correspondents.” I was like, “This is my career now? Now I’m a reporter?” I didn’t know anything about The Daily Show. This was before the first anniversary with Craig Kilborn. I watched it the night before I went. I didn’t like it. But I went over there and said I just loved it. I thought it was fantastic. The people there said, “Hey, so, you were a member of the Second City?” Yeah. “And you like, wrote and produced a TV show, a sketch show?” Yeah. “You were on The Dana Carvey Show?” Yeah. “And you’ve written for Saturday Night Live?” Yeah. “And now you’re a reporter for ABC News?” I go, “Yeah.” They were like, “You’re genetically engineered to do this job!” So I get the gig and I did that for a while, off and on. They weren’t thrilled with me.

You were also doing Strangers With Candy.

The third season of Strangers, I really wasn’t around there at The Daily Show, because it was really intensive and Paul Dinello and I were writing every word and breaking every story for Strangers. During that period, this guy named Jon Stewart took over The Daily Show. I knew Jon around from Short Attention Span Theater. My wife knew Jon, which was strange. When he got the gig, she was like, “What’s Jon Leibowitz doing up there?” She knew him back when he first came up to New York. His roommate dated her roommate or something like that, so he’s this quiet guy in the corner drinking an Amstel Light all the time. “He’s not funny. What’s going on?” So she knew him before I did. When I came back for the 2000 campaign, I remember the first day I really came back to the Jon show — I didn’t do much his first year — we hit it off immediately. I could feel that he was injecting the show with purpose. He invited us to put our own thoughts, to put our own feelings, to put our own editorial position in what we were doing. We weren’t widgets to him. We were creative partners. I realized immediately that I had kind of stumbled into the best possible job on TV, in the second greatest campaign of all time. We thought, at the time, “How could it possibly be stranger than this?”

So Indecision 2000 — was that the first introduction of the character Stephen Colbert?

In the ’90s, but specifically after 9/11, in the early aughts, punditry became this tremendous cash cow, because the nation’s whipped up into an emotional froth as it well should be, and punditry harvests emotion for profit. The folks at The Daily Show — I remember [co-creator] Madeleine Smithberg saying to me, like, “We want to do something that’s pundit-based and we think it should be you.” And so we started doing a commercial called “The Colbert Report” within The Daily Show. It was just an ad for a show that didn’t exist, called The Colbert Report, and I was “Stephen Colbert.” “Some people give you the truth, some people give you opinion, well, he’ll give you neither!” I forgot it was, something like, “It’s the no-fact zone!” That was when we first came up with the “no-fact zone,” and “Colbert: It’s French… bitch.”

And Bill O’Reilly was your primary model for the character?

Oh yeah, well he’s the king! If you’re going to model punditry, there were other people, like Aaron Brown, in a way, Anderson Cooper, bright as a shiny new penny, Aaron Brown, who would kind of like mull over the news and just have his moment of somewhat Ed Murrow-esque reflection on the day, but a little bit also adjunct professor of poetry, but there was no denying was O’Reilly. The number of words that could come out of that man’s mouth, and with seeming sincerity — I’ve never been able to figure out if O’Reilly meant what he said — over the years I have different levels of belief.

What were your personal feelings about this guy?

O’Reilly? I mean, I watched him professionally. I don’t think I would’ve watched him for pleasure. I watched him professionally, he was a model [for the character]. He just seemed like a bully. I don’t like bullies. I was bullied. Like a lot of people in comedy, I was bullied when I was younger, so he just seemed like a lot of bullies I knew growing up. It’s incredibly enjoyable to inhabit that skin, because then you just give yourself over. It’s sort of easy to improvise that person, because you are giving into your appetites, including your appetite to always be right, which is one of the greatest appetites. I really enjoyed him, because I really do think he’s a well-intentioned, poorly-informed, high-status idiot, which was my model.

So how did it become a show?

I really liked where [The Daily Show was] going with Jon, but I wanted to leave because there’s only so much I could do. Jon was always going to be the guy with the ball, and well he should be. There’s no greater runner. He’s the master, but I knew I could only do so much for him. It was a beautiful note, but only one note that I could do for him in his chorus of correspondents, and he wanted to do something with me. First, we pitched a show to NBC, which they bought the pilot idea — it would’ve been a good old sitcom — and then didn’t make the pilot. Then Comedy Central said, “Do you want to do a spinoff show of The Daily Show?” Jon and I talked about it and we said, well, “What about The Colbert Report?” We literally met for 45 minutes and — I have this page still on my Microsoft Word — and that page is just a scattering of words, but you look at it and go, “Oh yeah, that’s The Colbert Report.”

And the thesis was there from the start — truthiness, calling people out for their bullshit.

To be the bullshit. That was it. Everybody can smell bullshit. Our attempt was to manifest the turd. I am the turd in the punch bowl of our public discourse. That’s what I was trying to be. The thing we used to say is, “If you see something in politics or in entertainment or in the media, the closer it looks like me, the less you should trust it.”

You and Jon, separately and together, as much as you guys often like to downplay it, really became a primary source for a lot of people who maybe don’t consume traditional news media. When along the line did you realize that was the relationship a lot of people had with you and did it add a sense of responsibility on top of being funny?

I don’t want to speak for Jon, but I never heard him downplay, or I wouldn’t want to downplay, if people said they were informed by the work that I did. I think what I would say — and I think I’ve heard Jon say the same thing — is that we’re not downplaying where people got their information, but that’s not our intention. The information is there so that we can do the jokes on this information that’s very interesting to us. You can’t do these kinds of shows — The Late Show or the shows that I did before — without caring. Without giving a damn what you’re talking about. I mean, you can, but boy, that’ll get to pretty grinding work if you don’t have some emotional attachment to it. We’re running our jokes off of something that people care about and that is given a status of importance because it’s in the news. If people say that we influence them, that’s fine. I can’t dictate how people feel and what people get from the work that I did. I would only say that’s not the intention. Our intention or my intention and my responsibility always remains the same. It’s to tell jokes.

So it’s April 2014 and David Letterman announces he’s going to retire. How soon did you think, “I’m interested in this”?

Well, the very first thing I said to my agent [James “Baby Doll” Nixon] when I found out that they were making some overtures — it wasn’t a certain thing — was, “Baby Doll,” I said, “Baby Doll, the last thing I ever thought I’d do next is something harder.” And he said, “This won’t be harder! It’ll be easier. It’ll be easier, because you don’t have to do the character or anything like that.” Well. God bless him, he was wrong. It is a harder job. It is a harder job. But, as I said, I was wondering if they’d ever ask me. It was not my ambition, because I thought, I have always been something of a selective taste. I’m an acquired taste. That’s why cable seemed right for me. Do they really want to take a risk on me? On CBS? Because they know they’re higher, right? And Les was like, “No, this is what we want. We want to do something different.” My sister Mary was in town, and I was like, “Listen, I’ve got this thing, it’s all happening very fast, it’s possible.” And she just smiled. And I went, “Ugh! If I end up getting this gig, and this thing ends up being successful, somebody at CBS should send you flowers. I’m taking it because you just smiled.”

How was the handoff? Was Dave friendly, helpful, whatever?

He was so nice. Dave had always been really nice to me when I would come over. I was lucky enough to come on his show 10 times. A nice round number. Oh God, I always loved coming on! I’d go home and watch the show and just watch Dave’s face, to see, is he was really interested in what I was saying? Did I really make him laugh? That was a huge joy, if you could make Dave, for real, laugh. Really surprise him with a story. That was the greatest feeling in the world. So he’d always been really nice to me, and as soon as I got the gig and it was announced, he called me up. Actually, my assistant just found the transcript of our conversation. As soon as I got off, I wrote down everything that we said to each other so that I could remember it, and she found it the other day. Shortly before he left, I said, “Can I come talk to you?” And he’s like, “Sure.” I came over and I met him in one of these offices on this floor, and just had a couple bottles of water, and we sat there and talked and I asked him a ton of questions. He was extremely gracious about it. At one point, I said, “Do you mind me asking you all these questions?” And he said, “Nobody’s ever asked me these questions before.” And I said, “Really, never?” And he said, “Who would know to ask and who’d care what the answer is?” I was asking things about how to play this space and what his decisions have been — literally, “Why’d you put your desk there? Where do you put your producers? How do you deal with the balcony as opposed to the floor?” I’ve always thought that must be hard to deal with two separate audiences like that, because this theater is split up in a very interesting way, as I’ve discovered. “Where do you hide from your producers when you don’t want to be found?” That made him laugh. He was like, “I’ve got a great place for you and told me it later.” I haven’t used it yet.

You didn’t want a Late Show showrunner at first.

Absolutely. Why would I need a showrunner? I ran my old show. I’ll run the new one.

So eventually what made you recognize the need?

I lost my mind! What are you talking about? I couldn’t sleep at night, because A) clearly, aesthetically, or in terms of having an editorial intention, the show was not coalescing. People didn’t know what they were going to get. They didn’t know what it was about, because neither did I. I’d thrown out the baby with the bathwater in trying to be my character. I also threw out, kind of, my interests, which led to the character, which was politics, or just what happened today? What is the conversation that’s happening today?

What were you doing instead?

I don’t know. Very light, small stories. Maybe one big story, but we weren’t telling it in a story form. Just a couple of jokes and then we’d move on. Whereas, what we really are, as my exec Tom keeps reminding me, “Well, we’re storytellers!” We can’t just do one joke. We want to tell the story to the audience of why we even wanted to tell one joke about this thing, or why it’s interesting. It might be something that is the conversation. But also, we came to this realization that we’re not there at the old show because, I don’t know, we were often not doing the story that Jon did that night. We were doing other stories or stories with a little bit of a longer build to them, like more long-read kind of stories. We had to inform the audience a lot. We were breaking news to the audience unintentionally. Here, we learned that that’s not the job. Really, what works in one of these shows — at least, in my experience — is I’m going to talk to you about the thing you’ve already been talking about today and we’re going to give you our take on this thing that everybody’s been talking about, to give you some context, and maybe calm you down about it. That took a long time for for us to figure out, and we didn’t have the time or the space to figure that out until Chris Licht came on. Until I had an honest-to-God showrunner.

April 2016, you now have a showrunner, so you can focus more on the comedy?

Purely. Our deal was, he said, “Any moment you’re not thinking about comedy, I’ve failed.” And I said, “Let’s shake on it. You want the job?” You can boil down a two-hour conversation to that sentence. It’s a deal.

Last year, you were not an Emmy nominee; this year you’re an Emmy nominee, your primary competition has flipped and people can’t seem to get enough of it. How are you different?

I hope so. I’ll tell you, there’s a lot of things that have changed. I have an even deeper respect for Kimmel and Fallon and Conan and the people who came before us. I always respected their comedy, but I really respect them professionally. I didn’t know what they were doing until I got here. I’m in awe of a guy like Dave, doing 32 years, or Kimmel — what is Kimmel, now, 17 years? 15 years. Like that. I’ve always been friends with those guys. In late night now, people get disappointed that there isn’t a feud, but now I actually have a deeper respect for all of them than I did before. I’ve learned to trust my staff, because, being a control freak is mild form of distrust, if you know what I mean. Doing the live shows — we’ve done 17 or so over the past year — made me trust the staff and goddamnit, they’ve just killed it. They’ve done a fantastic job. I so admire what they’ve achieved and how the show now is far more bottom up, how they bring the ideas. I’m so grateful for the work that they’ve done. I’ve allowed myself to become sort of a pure performer now. I don’t try to produce the show in my head. People ask me, what’s going to happen today? I say, I just work here. I’ve been able to let go of the reins of control to — I don’t know if I can say to a large degree, that’s for someone else to say — but for me, it feels like an enormous degree. I walk into a meeting and Chris might say to me, “You’re not part of this meeting.” I go, “OK, I’ll leave,” which I think was a shock to people, because there was no meeting I was not in before. For years, for a decade. Letting go and just enjoying being on stage with the audience. That’s kind of where I realized why I took this job. I wanted to change as a performer. I wanted to change what my responsibilities were on a daily basis. I just wanted to go out there and do jokes for people. They might be about things, like I said, people think aren’t significant, but I want to go out there and do jokes for people. I want to go out there and be interested in my guest. The last two years has allowed me to do that. I could not do that for that first year. Chris gave us the space to do it, and then me trusting my staff allowed me to let go and just be the guy on stage. That’s the only way I could reveal myself, I could be myself for the audience.

And are you enjoying it more?

Oh, I love it! I love this job. I couldn’t love it more. This feels, right now, like the first year of the old gig. There’s a sense of excitement, and I hope, I hope that is throughout the whole building, that people feel like they’ve created something new, that wasn’t here a year ago and they paid their dues in that first year. It was hard on everybody. It’s just as hard if no one’s watching.

#Caps #Colbert #Comeback #Emmys #Hosting #Jokes #QA #Stephen #Wanted #Year

0 notes