#also I need to lock in on the PhD applications while also focusing on my Arabic classes so I can’t be writing too much rn

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I feel like Crosshair’s (the rest of the batch’s too tbh) reaction to the people of Pabu would be like my reaction when I moved from the city I spent most of my life in to the one I went to college in. My home city has a (very well-deserved) reputation for being full of rude people (amongst other things) so I was used to that and didn’t think anything of it. However, when I moved to a different city for college and was at the supermarket someone in line with me started chatting with me and complimenting my outfit, and I was trying to act normal because internally I was freaking tf out I was like “who is this person and what do they want from me? Oh my goodness what if this is like the intro of a true crime show?” So then after I pay I RUSH to my dad and am looking over my shoulder like “we need to leave and be careful that person was very suspicious and asking how my day was and complimenting my outfit.” And my dad was like “umm…people are just friendly here? We’re not in X anymore.” It took a while for me to get used to it and I still haven’t fully.

But yeah I feel like that’s what Crosshair’s first reaction to Pabu would be.

#I want to write this#I have so many Pabu things in my drafts but they’re all like half-baked#also I need to lock in on the PhD applications while also focusing on my Arabic classes so I can’t be writing too much rn#but oddly enough writing fanfic helps get the academic writing juices flowing as well so there’s also a strategy#also no my home city is not NYC#plus NYC gets a bad rap people there are so friendly they’re just direct and no frills about it#like where else do you see some guy see a mother struggle to carry a stroller down the stairs and just carry the stroller for her#and then just go about his day like nothing happened#star wars tbb#star wars the bad batch#the bad batch#tbb crosshair#tbb pabu#pabu

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

141. Elly Thomas

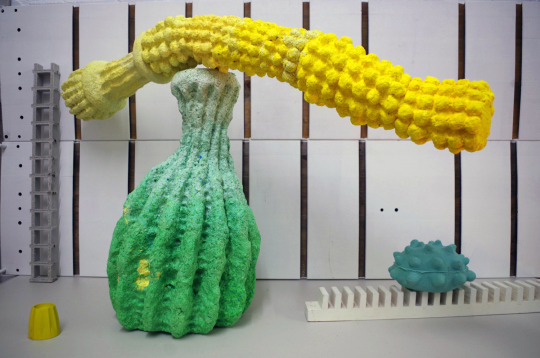

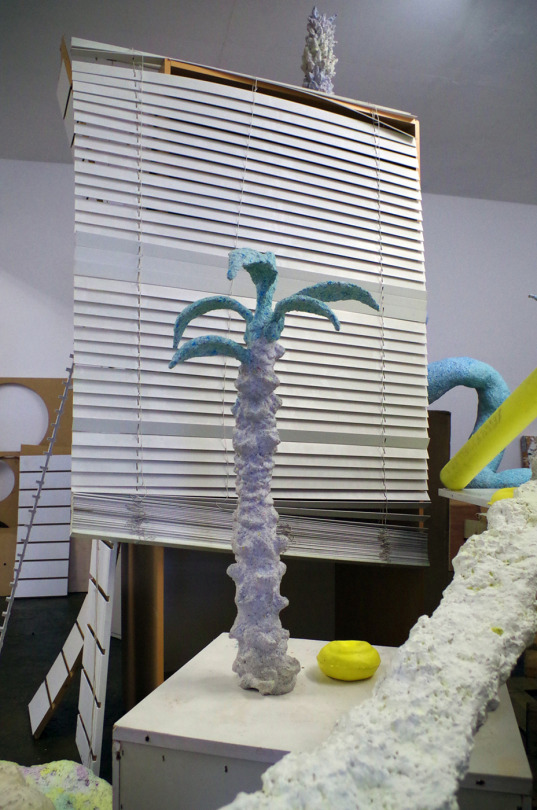

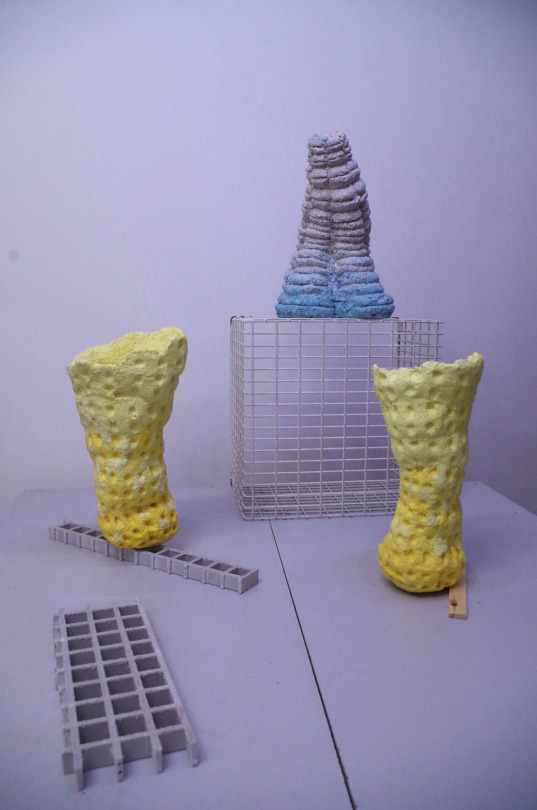

Elly Thomas, ‘Czar’, 2017. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

Elly Thomas is an emerging artist who uses sculptural forms to navigate how childhood play can inform adult creative processes. Creating a series of forms, which are then combined into various improvised assemblages, Thomas uses these impermanent structures to explore animism and autonomy of objects. Having completed a PhD in 2013 at Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, where her thesis was titled ‘Play as Evolving Process in the Work of Eduardo Paolozzi, Philip Guston and Tony Oursler’, Elly is now a leading mind on Paolozzi and Guston’s practices and will soon be releasing a book with Routledge discussing their processes and output. Here, Thomas talks with Charlotte Barnard for Traction.

You create sculpture and drawings, which use childhood play as set of paradigms to inform adult creative practice. How did you come to be so interested in this line of enquiry?

It was while I was enjoying working with children on an art project that I began noticing parallels between the way the children spoke about their work and my own ongoing concerns. Namely, at its most basic, we were concerned with transforming matter into something that seemed animate, that seemed to have a life of its own beyond one’s control, much as the way one would think about one’s toys as a child. So not representing something, but inventing - regarding a drawing or sculpture almost as a living thing, as a thing in itself.

I thought perhaps this space for play continued into adult life. I didn’t need to pretend to be a child again. How could I? It would only produce some sort of faux naivety. Instead I wondered whether I could learn from the children in a way that could be applicable to my own ongoing concerns, through a focus on animism and its expression through play methods, processes and objectives (rather than aesthetics).

Elly Thomas, ‘Kits and Building Blocks- Stage 1’, 2016. A collection of sculptures and found objects used as a kit of forms with which to improvise and experiment during a solo show at ASC Gallery. Mid-show the installation was dismantled and reconfigured. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

You create 'kits' of forms, which can then be assembled freely into a multitude of further configurations. What is it about this performative and non-static form of object creation that is so important to you?

This follows on directly from an animistic engagement with material. This particular form of engagement with matter had suggested that the landscape of play continues to age, evolve and develop throughout adult life. From here I asked ‘How can one treat sculpture and drawing as if they’re ‘toys’ as much as ‘art?’ So getting away from thinking in terms of a finished object or working towards a pre-visualised image, but instead finding a range of ways to experiment with these objects to see what they do, rather than the making existing as an end itself. So for me, making objects is just stage one. After this they become toys that are allowed to ‘live’ through endless reconfiguration.

The objects you make take on biomorphic forms, and seem to me to be suggestive of the domestic. Does this reading of them ring true?

It’s less about the domestic and more about the world of mass production set against the biological world. I’m interested in confusions between the two realms. This exists in childhood (after all what is a toy if not a man-made object that is confused with the living world), and in fact the pioneering child psychologist Jean Piaget asserted that children are often unable to distinguish between the mechanical and the biological – for children where there is movement there is life.

Elly Thomas, ‘Kits and Building Blocks- Stage 1’, 2016. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

I explore this confusion through parallels between the biological and manmade that centre on the functional – on engineering, living systems and potentially infinite structures comprised of a simple series of building blocks. This focuses on repetition and symmetry in the world of mass production as opposed to organic repetition (where no repeated form is identical) and organic asymmetry (anything that grows will inevitably be asymmetric).

However, I think you have hit on something about the domestic and the biomorphic, because both my parents are biologists and on the walls of my childhood home there were many reproductions of images from D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s book ‘On Growth and Form’. The landscape of childhood would seem to be re-emerging again! So, as is often the case, other people are able to see what you’re doing more clearly than you are yourself!

Elly Thomas, ‘Kits and Building Blocks- Stage 1’, 2016. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

What is your approach when initially coming to make these forms? How much do traditional considerations of form, material, texture and colour influence the outcome?

Everything comes from collecting. I collect images, objects and junk with no idea how things are going to come together (play is by definition open-ended). I’m also continually sketching, but allow myself to forget the source material the images are based on. This drift allows the forms to gain an independent identity, rather than be left locked in the world of representation. When it comes to moving the forms beyond the sketchbook and into sculpture I choose materials that will force time and change to be built into the process. I want the resulting forms to have ‘grown’ through a response to gravity and changing conditions. The sculptures then exist in physical time - time as layering, stacking and etching.

Elly Thomas, ‘Kits and Building Blocks- Stage 2’, 2016. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

You have written extensively about the practices of Philip Guston and Eduardo Paolozzi. You have a forthcoming book for Routledge titled, 'Play and the Artist’s Creative Process: The Work of Eduardo Paolozzi and Philip Guston'. What is it about their individual practices that so interests you? How much influence has your research into their working methods had on your own?

I was initially drawn to their work through their particular relationship with popular culture. Both artists seemed to have engaged with pop culture in a way that didn’t seem to fit into existing art historical labels (even if Eduardo Paolozzi is often described as the Father of British Pop Art, an epithet he first courted and then dismissed).

I began making comparisons between the cultural landscape of their individual childhoods and the work they made during artistic maturity. In the case of Paolozzi one could see a striking connection to toys that would have been available to him as a child, with Guston there is obviously a connection to the comic strips he loved as a boy. But more significantly, as I dug deeper I began to discover that both artists had a recurrent interest in animism and a need for the unexpected outcome.

From here I began to explore their studio methods and processes through the lens of play. Both artists have made a big impact on my work in terms of expanding the possibilities for play within a studio environment. Paolozzi and Guston were endlessly experimenting; they offer artists a vast tool kit of methods that allow one to reconnect with the landscape of play.

Elly Thomas, ‘Kits and Building Blocks- Stage 2’, 2016. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

Your sculptural work has recently been transformed into a 2D, static image for London Arts Board. It is an unexpected and intriguing departure for this facet of your output, transposing its normal mutability into something fixed, especially considering drawing seems to be such an integral element of your practice. How did this come about?

The London Arts Board is an innovative public arts project founded and run by Liberty Rowley on a notice board on Peckham Road. In the current climate with drastic cuts to arts funding and creativity and play pushed to the margins of the school curriculum, public art seems more important than ever. I think in many ways the ‘where’ is the most urgent political question for art – how one makes space to assure that access to the arts is available for everyone.

As to the static nature of my new work – I don’t see the piece as finalised, in a sense it’s on pause until the sculpture elements are reconfigured. In fact I’ve already been playing with different combinations of the elements in my studio. Philip Guston described his paintings as ‘pauses’ and imagined all his paintings as one work. I find that a very potent idea.

Elly Thomas, ‘Kits and Building Blocks- Stage 2’, 2016. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

What have you got coming up?

In mid-February an Eduardo Paolozzi retrospective opens at The Whitechapel Gallery. I’ve been working on the catalogue both as a contributing author and researcher. I’ll also appear in a short film discussing Paolozzi’s print suite General Dynamic F.U.N.

Interview by Charlotte Barnard.

You can see Elly’s work for London Arts Board online at http://londonartsboard.blogspot.co.uk/

You can also see it in person at the corner of Peckham Road and Vestry Road, Camberwell, London.

To see more of Elly’s work and to keep updated with her upcoming events, please follow http://www.ellythomas.com

#Elly Thomas#animism#play#growth#form#eduardo paolozzi#philip guston#LondonArtsBoard#ASC#drawing#biologocal#biomorphism#routledge#contemporary art#emerging art#slade#mass production#mechanical#childhood#sculpture

1 note

·

View note

Text

Drawing courtesy of the author

By Darya Tsymbalyuk

Just before the official lockdown was announced in Scotland, I moved all of my office plants home. There was no space for them in my room, but I rearranged my furniture to accommodate my office plants since they had been my closest companions during the crisis. There are numerous platforms, including Vogue and Independent, which have written about the positive effect houseplants have had on people during the lockdown, including their positive contribution to our mental health. Yet there are fewer platforms that have written about the effect the lockdown has had on houseplants left in apartments and offices, and even the ones that do, stress the importance of people’s wellbeing rather than the wellbeing of plants. For example, The Guardian quotes Hugo Meunier, a founder of the company in Paris that is rescuing plants, as saying:

Obviously, people had much more important things to worry about during the lockdown, but it’s depressing to come back and find the plants dying. And it’s good psychologically for people to think we will try to do something for the plant.

And the The New York Times quotes Ms. Vassilkioti, the founder of a company that installs and maintains plants in commercial spaces, as saying:

[…] it’s OK to say ‘goodbye’ and get a new plant. Plants are supposed to make us feel good, and right now we have so much other crazy stuff going on, we don’t need to feel sad.

In both of these quotes, plants are presented as a commodity, which are supposed to make us feel better while we are isolating in our homes, and which can be easily discarded and replaced if the realization that a plant is a living being that can die, and not an object, upsets us.

Lockdown companions (Photograph courtesy of the author)

Yesterday, for the first time since the lockdown, I stopped by the main library building of my university town. Last year, a new collaboration space was opened at the lowest level of the library. The room has been home to a variety of big and beautiful houseplants, among which are a Ficus benjamina (Weeping fig), a Dracaena, and a Schlumbergera. A massive glass window frames the collaboration space, and you can see the plants from the outside. When I visited the window for the first time in more than three months, the plants looked dry and wilted, their leaves fallen to the floor; the Schlumbergera was now a shade of red. Most of the plants still had green leaves that stood out among the dead, wilted ones. The leaves were pressed against the window, and it was just the glass separating me and them; and this glass was fatal: it meant that I was outside just like the lawn behind me, which was not dependent on humans to be watered; and it meant that as close as I was, and as much as I wanted, I could not reach the plants to offer them water. For now, glass separates us, and ironically, I can see my own reflection better than I can see the plants.

Plants in the collaboration space (Photograph courtesy of the author)

Plants in the collaboration space (Photographs courtesy of the author)

Plants in the collaboration space (Photographs courtesy of the author)

The vision of plants as immobile leads us to see them as passive and, therefore, as things that can be commodified and treated like objects. This is particularly true for houseplants, many of which are sold at shops alongside groceries, household items, and furniture. In literature on interior design, plants are often seen as accessories that help to create nicer environments for humans. The former Soviet Union, where I was born, developed the concept of phytodesign, which entailed the “design and practical application of plants in artificial environments.” [1] Giovanni Aloi, an author and editor of Why Look at Plants? The Botanical Emergence in Contemporary Art, writes about the “enforce[ment] of biopolitical regimes designed to standardize vegetal anatomy,” [2] which help to produce perfect specimens for the interiors of our houses and offices. The objectification of plants is perfectly demonstrated by the trend of coating succulents with bright colors and glitter. In the UK, you can often see painted succulents in Tesco or other supermarkets, particularly around Halloween or Christmas. Spray-painted succulents are there to please and amuse demanding customers, with little thought given to the effects of the paint on the plant (even if it is non-toxic) and how it effects their ability to stay alive and photosynthesize.

Plants surround us both indoors and outdoors, but we often see them only as a background. Plant blindness is a term referring to our inability to notice plants in spaces [3]. I remember many plants in different university buildings, some in the corridor on the way to my department, some in the lobby, some at the counter at the student services center. Walking through the empty streets of the town, I cannot stop wondering what happened to those very particular plants I passed by and observed almost every day.

Humans domesticated plants to make them live with us indoors. Most of the houseplants I keep in my room in Scotland originally come from very different climates. Isolated from their natural environment and being placed in pot, a houseplant in a room immediately calls for the creation of a collaboration space in which humans promise to provide water and food, as well as a larger pot when needed, in exchange for the plant’s company. This means that the collaboration space of the library is not just a nice place where students can meet and discuss projects but also a multispecies collaboration space between humans and plants. The lockdown and closure of the library disrupted this multispecies collaboration. There was no access to the building, humans had left, and the plants remained. There was no evacuation plan for the latter.

The question of multispecies relations in a moment of crisis is something I focus on in my PhD research. I study narratives of human-plant relations and their (re)configuration during and after experiences of displacement from the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in Ukraine. Since the outbreak of military conflict and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, more than 1.3 million people have been internally displaced from affected areas, according to the number of people who have registered in government-controlled territories [4]. The actual number is much higher.

Just like military conflict, the Covid-19 pandemic is a crisis to which humans have had to respond quickly, making urgent decisions, including what things to take with them from their offices before the impending lockdown. Seeing the window of the collaboration space of the library made me recall the many voices of my interviewees sharing stories of plants that they could not take with them as they fled, and that slowly died in their locked apartments. It is important to note that many internally displaced persons did not know that they were leaving for a long time. Since the conflict began in spring, many went on an unplanned vacation and hoped that things would calm down by the time they returned. In one of the interviews, a woman whom I call Iryna in order to preserve her anonymity recalls coming back home after several months of absence. Iryna was abroad when the conflict escalated and could not return home as planned. She recounted the experience of returning to her apartment after a long period of absence:

And when I entered the house… we had a lush plant in a big white pot, a hibiscus with red flowers… And I saw a wilted hibiscus… The rest… felt like in a film about the Apocalypse, yes… Everything remained where it was, toothpaste, toilet paper, and there was a feeling that someone left for 5 min… but the wilted plants – and I’ve got a lump in my throat…

Iryna’s description of the hibiscus is not much different from my experience of plants in the collaboration space; they are a reminder of disrupted multispecies relations. Wilted leaves are a plant’s final expression of their own aliveness, if only through death. The return journey that Iryna describes before entering her home is difficult and dramatic, but it is the death of the hibiscus that makes Iryna realize the irreversible rupture of displacement.

Stories about human-plant relations in the moment of crisis are not always about abandonment and death. For example, in one of my other interviews, Oleh [5] went through a long process of obtaining military permissions to return to the conflict area and evacuate approximately 40,000 plants from a plant nursery. During the interview, Oleh’s wife Oksana [6] comments on the fact that while Oleh was trying to obtain the necessary permissions, a lot of people found it surprising that he was so determined to evacuate the plants. In times of crisis, being concerned with plants does not seem to be the most pressing problem for most. Political commentary and the media tend to emphasize human life. In Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? Judith Butler analyzes the way the media frames and portrays certain lives as less valuable and, therefore, as less “grievable” than ours. In the introduction to her book, Butler writes:

…specific lives cannot be apprehended as injured or lost if they are not first apprehended as living. If certain lives do not qualify as lives or are, from the start, not conceivable as lives within certain epistemological frames, then these lives are never lived nor lost in the full sense. [7]

Butler focuses on human lives only; however, this argument can be easily extended to nonhuman lives. The lives of houseplants left in offices or plants in Oleg’s nursery are non-grievable precisely because we tend to see them as either objects or as non-sentient beings, and as the articles in The New York Times and The Guardian quoted earlier show, the death of plants potentially only matters in light of the sadness that it inflicts on humans.

I wrote to the library today offering to pick up the plants from the collaboration space if there was a possibility of accessing them. In most human-plant relations, whether it is the cultivation of monocultures or flower and houseplant markets, we often see a reflection of our own needs and desires. The Covid-19 crisis has made us question our relations with the nonhuman, whether it is the discussion about wet markets or the return of wildlife to urban areas. The UN, WHO, and WWF International claim that the destruction of the environment results in pandemics such as Covid-19. However, it is the threat to human lives that brings these discussions forward. Once again, it is our own reflection that we are concerned with the most. What is truly important though is continuing to question if we are capable of seeing nonhuman lives not just as resources and commodities but as a valuable in and of themselves. The window at the collaboration space of the library is a tragic example of our consistent failure to build a relationship with other species that truly recognizes their right to live.

Postscript Several days after I submitted the draft of this essay, the library replied to me and promised to do their best in taking care of the plants. However, many more remain locked in other office spaces.

[1] A.M. Hrodzinskiy, Sered Pryrody i v Laboratoriyi (Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 1983): 122.

[2] Giovanni Aloi, Why Look at Plants? The Botanical Emergence in Contemporary Art (Leiden, Boston: Brill Rodopi, 2018): 184.

[3] J. H. Wandersee and E. E. Schussler, “Preventing Plant Blindness,” The American Biology Teacher 61, no. 2 (1999): 82–86.

[4] UNHCR Ukraine, “Registration of Internal Displacement,” UNHCR Ukraine, published 04 June 2020.

[5] The name has been changed.

[6] The name has been changed.

[7] Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (London and New York: Verso, 2010): 1.

Lockdown and Locked-In: Houseplants and Covid-19 Drawing courtesy of the author By Darya Tsymbalyuk Just before the official lockdown was announced in Scotland, I moved all of my office plants home.

0 notes

Text

Sending clearer signals

In the secluded Russian city where Yury Polyanskiy grew up, all information about computer science came from the outside world. Visitors from distant Moscow would occasionally bring back the latest computer science magazines and software CDs to Polyanskiy’s high school for everyone to share.

One day while reading a borrowed PC World magazine in the mid-1990s, Polyanskiy learned about a futuristic concept: the World Wide Web.

Believing his city would never see such wonders of the internet, he and his friends built their own. Connecting an ethernet cable between two computers in separate high-rises, they could communicate back and forth. Soon, a handful of other kids asked to be connected to the makeshift network.

“It was a pretty challenging engineering problem,” recalls Polyanskiy, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT, who recently earned tenure. “I don’t remember exactly how we did it, but it took us a whole day. You got a sense of just how contagious the internet could be.”

Thanks to the then-recent fall of the Iron Curtain, Polyanskiy’s family did eventually connect to the internet. Soon after, he became interested in computer science and then information theory, the mathematical study of storing and transmitting data. Now at MIT, his most exciting work centers on preventing major data-transmission issues with the rise of the “internet of things” (IoT). Polyanskiy is a member of the of the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems, the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society, and the Statistics and Data Science Center.

Today, people carry around a smartphone and maybe a couple smart devices. Whenever you watch a video on your smartphone, for example, a nearby cell tower assigns you an exclusive chunk of the wireless spectrum for a certain time. It does so for everyone, making sure the data never collide.

The number IoT devices is expected to explode, however. People may carry dozens of smart devices; all delivered packages may have tracking sensors; and smart cities may implement thousands of connected sensors in their infrastructure. Current systems can’t divvy up the spectrum effectively to stop data from colliding. That will slow down transmission speeds and make our devices consume much more energy in sending and resending data.

“There may soon be a hundredfold explosion of devices connected to the internet, which is going to clog the spectrum, and there will be no way to ensure interference-free transmission. Entirely new access approaches will be needed,” Polyanskiy says. “It’s the most exciting thing I’m working on, and it’s surprising that no one is talking much about it.”

From Russia, with love of computer science

Polyanskiy grew up in a place that translates in English to “Rainbow City,” so named because it was founded as a site to develop military lasers. Surrounded by woods, the city had a population of about 15,000 people, many of them engineers.

In part, that environment got Polyanskiy into computer science. At the age of 12, he started coding — “and for profit,” he says. His father was working for an engineering firm, on a team that was programming controllers for oil pumps. When the lead programmer took another position, they were left understaffed. “My father was discussing who can help. I was sitting next to him, and I said, ‘I can help,’” Polyanskiy says. “He first said no, but I tried it and it worked out.”

Soon after, his father opened his own company for designing oil pump controllers and brought Polyanskiy on board while he was still in high school. The business gained customers worldwide. He says some of the controllers he helped program are still being used today.

Polyanskiy earned his bachelor’s in physics from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, a top university worldwide for physics research. But then, interested in pursuing electrical engineering for graduate school, he applied to programs in the U.S. and was accepted to Princeton University.

In 2005, he moved to the U.S. to attend Princeton, which came with cultural shocks “that I still haven’t recovered from,” Polyanskiy jokes. For starters, he says, the U.S. education system encourages interaction with professors. Also, the televisions, gaming consoles, and furniture in residential buildings and around campus were not placed under lock and key.

“In Russia, everything is chained down,” Polyanskiy says. “I still can’t believe U.S. universities just keep those things out in the open.”

At Princeton, Polyanskiy wasn’t sure which field to enter. But when it came time to select, he asked one rather discourteous student about studying under a giant in information theory, Sergio Verdú. The student told Polyanskiy he wasn’t smart enough for Verdú — so Polyanskiy got defiant. “At that moment, I knew for certain that Sergio would be my number one pick,” Polyanskiy says, laughing. “When people say I can’t do something, that’s usually the best way to motivate me.”

At Princeton, working under Verdú, Polyanskiy focused on a component of information theory that deals with how much redundancy to send with data. Each time data transmit, they are perturbed by some noise. Adding duplicate data means less data get lost in that noise. Researchers thus study the optimal amounts of redundancy to reduce signal loss but keep transmissions fast.

In his graduate work, Polyanskiy pinpointed sweet spots for redundancy when transmitting hundreds or thousands of data bits in packets, which is mostly how data are transmitted online today.

Getting hooked

After earning his PhD in electrical engineering from Princeton, Polyanskiy finally did come to MIT, his “dream school,” in 2011, but as a professor. MIT had helped pioneer some information theory research and introduced the first college courses in the field.

Some call information theory “a green island,” he says, “because it’s hard to get into but once you’re there, you’re very happy. And information theorists can be seen as snobby.” When he came to MIT, Polyanskiy says, he was narrowly focused on his work. But he experienced yet another cultural shock — this time in a collaborative and bountiful research culture.

MIT researchers are constantly presenting at conferences, holding seminars, collaborating, and “working on about 20 projects in parallel,” Polyanskiy says. “I was hesitant that I could do quality research like that, but then I got hooked. I became more broad-minded, thanks to MIT’s culture of drinking from a fire hose. There’s so much going on that eventually you get addicted to learning fields that are far away from you own interests.”

In collaboration with other MIT researchers, Polyanskiy’s group now focuses on finding ways to split up the spectrum in the coming IoT age. So far, his group has mathematically proven that the systems in use today do not have the capabilities and energy to do so. They’ve also shown what types of alternative transmission systems will and won’t work.

Inspired by his own experiences, Polyanskiy likes to give his students “little hooks,” tidbits of information about the history of scientific thought surrounding their work and about possible future applications. One example is explaining philosophies behind randomness to mathematics students who may be strictly deterministic thinkers. “I want to give them a little taste of something more advanced and outside scope of what they’re studying,” he says.

After spending 14 years in the U.S., the culture has shaped the Russian native in certain ways. For instance, he’s accepted a more relaxed and interactive Western teaching style, he says. But it extends beyond the classroom, as well. Just last year, while visiting Moscow, Polyanskiy found himself holding a subway rail with both hands. Why is this strange? Because he was raised to keep one hand on the subway rail, and one hand over his wallet to prevent thievery. “With horror, I realized what I was doing,” Polyanskiy says, laughing. “I said, ‘Yury, you’re becoming a real Westerner.’”

Sending clearer signals syndicated from https://osmowaterfilters.blogspot.com/

0 notes