#allison bird treacy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Parable

“which is to say not an allegory. An opportunity for displacement. Faith steps into the footprint of a mountain, garbs itself in miniature birds. A debtor forgives a sheep for disguising itself as a son. Coins fall beside stalks of wheat and burn away thorns. Replace one part with another

to discover wine in your father’s urn. Neither grief nor drunkenness pleases the guests, but inside a fig, a wasp becomes a pearl.”

- Allison Bird Treacy, Parable.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Birds, LLC, $16

http://www.birdsllc.com/catalog/red

By Allison Bird Treacy

Erasure poetry, fundamentally an act of appropriation and reinvention, has been around a long time, but in 2017 it caught the attention of the New Republic. Since Trump’s election, reporter Rachel Stone noted, erasure poetry seemed to be undergoing a renaissance, specifically as a mode of commentary on Trump’s own pronouncements. In addressing this revival, though, Stone also observes the limits of erasure – the scope is restricted by the source, leading to the follow-up question, can erasure ever create something new? In the introduction to their 2018 collectoin R E D (Birds, LLC.), poet Chase Berggrun suggests that, at the very least, erasures can flip the script.

The poems in R E D apply the practice of erasure in specifically gendered manner. Based on Bram Stoker’s classic Victorian novel Dracula, Berggrun’s goal in R E D is to presents an alternative tale, “in which its narrator takes back the agency stolen from her predecessors,” to create something which is more than mere commentary. Their rules for construction, though – each poem is drawn from a single chapter of Dracula, with no alteration to the words – produce challenging, and not always productive, conditions under which to do so, as does the sheer length of the source text. Language is a tool, and Stoker’s language belongs to the master, leaving Berggun with white space as their primary means of alteration.

Typically, erasure poetry draws at least some of its power from use of white space; the silences are a central element. In working with such a lengthy text, Berggrun is forced to rethink how that white space will work, and while line lengths vary, the collection is largely made up of double-spaced lines, with occasional single-spaced stanzas interspersed. This use of double-spacing slows the pace of the poems considerably and, coupled with a heavy reliance on the word “I” to begin lines, turns the poems into lulling litanies. “Chapter II,” for example, begins:

I must have been asleep I must have been held in his trap I did not know what to do I waited in that nightmare I heard a heavy sound a noise of long disuse

Each line struggles to feel like a complete thought, and as Berggrun dispenses with punctuation throughout the collection, there is no impetus to join them. But there is also compelling use of white space throughout the collection, as seen in the fifth line above. Reminiscent of more tradition, short erasures, these applications of space serve as the reader’s only punctuation.

It may be a matter of pacing, but the most remarkable moments of R E D occur in the rare single-spaced stanzas. In “Chapter XV,” Berggrun reconstructs a section of text to read,

I start out lurid before outrage I unhinged explanation from its frame without permission without endorsement I violate limitation and I condemn the desecration of my body

While these lines lean equally heavy on the pronoun “I,” the single-spacing offers necessary propulsion to the words, setting them apart, unhinging them, even, from the framework otherwise imposed on the text. Similarly, the small break away from “I” as line opened in the line, “and I condemn” changes the readers’ internal metronome. Such disruptions are scarce, but forceful in their application in a text that is otherwise uniform.

Though – spoiler alert – Dracula’s former victim, the weak and delicate woman, wins in this version of the tale, Berggrun’s erasures are like many other: often compelling, but repetitive if only because they are bound to their source. It may take new language to go beyond comment, or in this case, beyond contradiction.

#birds llc#poetry review#poetry book review#book reviews#chase berggrum#allison bird treacy#red#erasure poems#nyc poetry#nyc poets

0 notes

Photo

Black Lawrence Press, 2018, $8.95 https://www.blacklawrence.com/acadiana/

By Allison Bird Treacy

Must we suffer what we predict, what we prophesy? In Nancy Reddy’s Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018), a collection filled with sibyls and saints, the act of prophesy carries a heavy load alongside the ethical implications of human activity. Indeed, the conjunction of the mythic and the scientific in Acadiana makes Reddy’s collection unique within the scope of ecopoetics, suggesting that we can love our personal mythology without eschewing responsibilities for our planet.

Having heard over and over that disaster is coming, having courted bad luck by adopting a big black dog, we are left to our own fates, but in the face of all this warning, Reddy declares the sibyls ready to abandon us. In “The Sibyls Swear Away Their Prophecy,” the mythical fortunetellers seem to have tired of us, declaring:

Do not come here

asking why your crops are taken by the waters

why the oyster beds are wind-wracked and scattered.

Go ask your robed men who teach the split-world after who read by rote that thin-skinned book of mercy and ruin

why this country is unseamed and stripped.

The sibyls have given their all and we have gone forward heedless of the consequences. Freely intervening throughout the opening of the collection, the sibyls will fall silent before it ends. And though it precedes this piece, Reddy seems to offer “Storm Pastoral” to startle us awake.

“Storm Pastoral” is perhaps the most dissonant of the poems in Acadiana, and not just because of its unusual visual structure, which underscores the strange new landscape that comes after the storm. Rather, in relating a radio report about a deer that has made its way into the waterlogged city, Reddy writes that it was

…like those men in the South Pacific

who survived shipwreck sharks the screams of other men rescue and when the hands descended from the rescue boats

the men’s skin was waterlogged and peeled off in sheets.

Of all scenes to be included in a “pastoral” poem, this one is stark and punishing, a reminder that even when help comes, it may be too late to change the course of things.

Guiding us through Katrina-era Louisiana, Reddy walks us through towns touched by oil rigs and storms, covered by mosquito spray and live oaks, and asks:

…if you prayed for mercy or wished away a strong storm’s landfall, weren’t you also wishing harm on someone else’s town?

(from “Holy Week, Acadiana”)

In other words, what does it mean to jilt the consequences of our actions? Though all is not hopeless, for Reddy it means that sibyls abandon their prophecy, that communities question their God, and that we all must look more closely at how our lives touch a changing ecosystem – even when the storm is in someone else’s town.

#black lawrence press#poetry chapbook#poetry review#nancy reddy#run and tell that reviews#allison bird treacy

0 notes

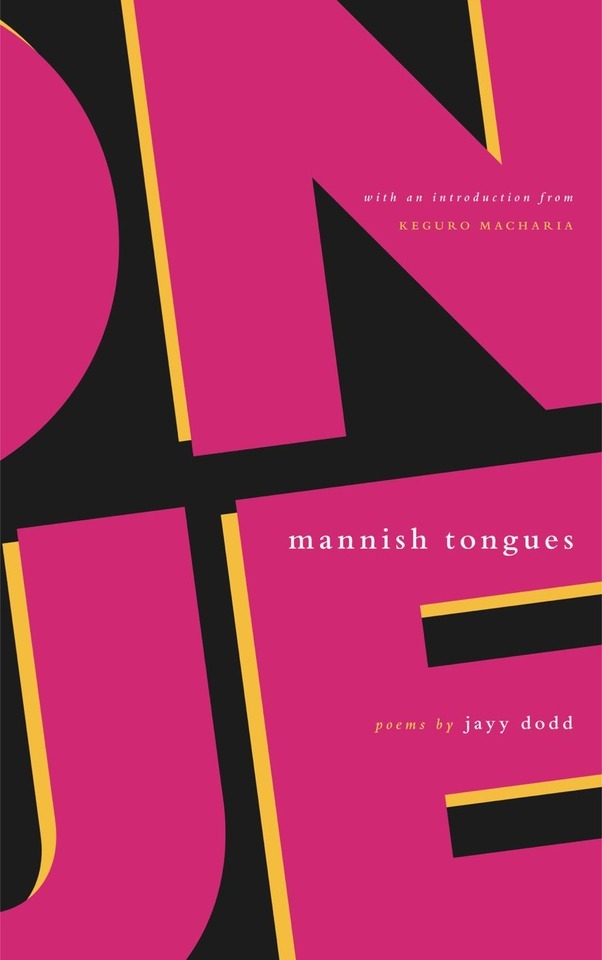

Photo

Platypus Press, 2017, $13.00 http://platypuspress.co.uk/mannishtongues

By Allison Bird Treacy

When we seek to magnify voices – of an individual, of a group – how do we go about it? According to Nick Cave’s 2011 installation, “Speak Louder,” the answer rests in the body. Silver spangled and forcefully resonant, Cave’s suits are sculptures, costumes, and instruments all at once, and rooted in ritual. And as the inspiration for Jayy Dodd’s poem by the same name, nearly everything that can be said of Cave’s “Speak Louder” can also be said of Dodd’s 2017 collection, Mannish Tongues. At its core, Mannish Tongues celebrates, mourns, and does this all while garbed in silver, demanding our attention.

Dodd’s Mannish Tongues contains prayerful, and riotous poems. Opening with epigraphs by Essex Hemphill and the Book of Proverbs and anchored by an array of core figures, including Tamir Rice, the artist Nick Cave, and Rodney King, Dodd’s poems are a liturgy of blackness, queerness, and boyness. In Dodd’s words:

if i fix my lips to speak themselves free, allow my voice to break in riot,

be vocabulary barreling through a nation’s mourning, be vernacular of bullets coming for the back of your throat. (from “Eloquent”)

A force to be reckoned with, these poems are necessary for our present moment.

In the church of Dodd’s poems, resurrection is a recurring theme. Because the Black body and the queer body are both continually subject to death, resurrection is a necessary part of their construction. After each death, one must return to the page and the poem. For Dodd’s speaker, this notion is instilled early in life by the mother, who is parent, preacher, and God in one. In “There’s Something Bout Being Raised In Church” Dodd writes,

i first learned fear as my mothers’ eyes, when i would act my age in the front row & that death was always subject to some sort of resurrection —

The constant fear of death that plagues the mothers of black sons is presented as inescapable repetition. It’s the oppression of living with the “end times/as regular occurrence” as the speaker in “Returning” notes. But returning and resurrection, they share a suffix, the “re-��� of repetition, the again and again that makes up any liturgy or rosary. Repetition is holy, as Nikky Finney once said and Dodd words play this out with every death, in each historical citation. It all comes back around.

Dodd meditates on the concept of the infinite monkey in their poem by the same name, though, the black body makes up this infinite populace. The infinite monkeys become

infinite Harambes infinite African bodies displaced infinite cages infinite Black mothers wailing in daylight for safe return

The list goes on. In the eyes of white society there is slippage between infinite monkeys of all stripes and “infinite Barack Obamas bopping out The Audacity of Hope.” The black body and the monkey’s body switch and fold into and over each other and the reader remembers how sympathy for Harambe, who holds space for this poem, exceeded any sympathy for actual black people facing needless death. And so the wailing goes on.

Dodd’s poems are rich in history, on poetic tradition as embodied in their “ars poetica” or “scene: waking up next to John Keats after a pleasant evening” and yet they balance all of their traditional art with vulnerability and transgression. Dodd dares us to come closer, to stand too close to choir boys (or girls), to unearth our own desire in the work. If it’s all been done before or could be done by infinite or immortal monkeys, in Mannish Tongues history is resurrected as the present with a new face, daring us to linger with this

#jayy dodd#allison bird treacy#mannish tongues#platypus press#poetry books#poetry reviews#national poetry month

0 notes

Photo

Silver Birch Press, $15 http://www.silverbirchpress.com/point_blank.html

by Allison Bird Treacy

The city is a song. Byron Lee & The Dragonaires fill a kitchen and neighbors shriek neighbors from a front porch; the author’s niece sings out an infant’s discovery and Stevie Wonder plays on the radio. This is the soundtrack supporting Alan King’s 2016 collection Point Blank from Silver Birch Press, pulsing through poems that deliver the urban scene as art piece.

Art in Point Blank is not just songs but also photographs on a restaurant wall, comic books, and the rich flavors of Trinidad’s traditional cuisine or a burger joint – and King weaves these together into an ekphrastic reflection on life as a Black man in America. The collection opens on the poem “Hulk,” a piece that, in a collection featuring several poems about superheroes, invokes images of the green comic book giant, instead positions the speaker as “defect” in the landscape because of his race –

Even the trees shudder at the sight of me walking the streets at night.

Though the trees may tower over him, they read the speaker’s race and transmit it back as fear.

In the honest tones signaled by its title, the collection offers equal parts critique of racialized violence and celebration of joy and innocence. And like the segregated scene represented in Ernie Barnes’ painting “Sugar Shack” from which one of the poems takes inspiration, King is committed to the intermingling of these two opposing forces and how together they constitute survival. The Black men and women in the painting

… danced as if it was the 1970s, the decade my parents emigrated here from Trinidad. U.S. soldiers were already dying in South Vietnam’s

rice paddies.

Art collides with personal experience collides with history and the violence of segregation becomes the pain of diaspora becomes the destruction of war. This slippage is where King pushes the limits of ekphrasis and turns Point Blank’s poems into Trojan horses, a hazard inside a gift, just as pain resides within pleasure and each poem delivers us deeper into King’s vision of the city.

Indeed, Trojan horses themselves appear several times in the book, as tattoos on cheating girlfriends and descriptions of friends who betray. Writing in “Getting a Little on the Side” of an undercover detective following a woman accused of cheating on her husband, King describes how the detective

… almost blurs the shot when he spots the woman’s Trojan horse tattoo on her left shoulder, the same one his ex-wife had on her right ankle.

The betrayal is palpable, inscribed as body art and then reinterpreted through both the camera and emotional lens gripped close by the detective.

Trust is a precious commodity for which, like the flavors of home, the love of a wife, there is no substitute. And trust is countered by figures like Trouble and Insecurity, who King draws into the poems like muses, named characters seeking to interfere and ignite an otherwise peaceful scene.

The poetry in Point Blank will leave you craving coconut bake and bananas, make you want to cook curry with the radio turned all the way up, simply to avoid leaving life unsavored. After all, King tells us, in a world that doesn’t love those on the margins, it could all be over too soon. Reading Point Blank we sneak in each moment of pleasure, taste “mom’s curry/lingering in every room, opening the house,” as we slip from Trojan horses and step into King’s depictions but also into our own lives.

#silver birch press#alan king#cave canem#point blank#poetry books#poetry reviews#poetry#poets#run and tell that

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Finishing Line Press, $14.99

https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/capricornucopia-the-dream-of-the-goats-by-paula-neves/

By Allison Bird Treacy

In the history of feminism, the kitchen is a sacred space. Indeed, as Barbara Smith once said, “the kitchen is the center of the home, the place where women in particular work and communicate with each other,” and in paulA neves’ 2018 chapbook capricornucopia (dream of the goats), the kitchen takes center stage from the very first poem, “Graciete.” Writing through the memory of the family kitchen as she does many times in the collection, neves’ spacious lines breathe out –

I will listen to her just once more

while she cradles the blade in one hand

insisting that I unravel.

The final stanzas of this poem set up a larger conceit for the collection, a combination of displeasure with the speaker mixed with a desire to understand her that runs counter to the speaker’s desire for inclusion in family traditions. That a certain degree of undoing is necessary to be legible as a same-sex attracted, gender non-conforming woman within an immigrant family is understood. As such, the blade that peels the potatoes also slices through the self-presentation of the speaker, though is does so tenderly as the hand “cradles the blade.”

One of the poems in which neves’ is most revealing about her relationship to family, gender, and sexuality, is the title poem, “Capricornucopia (The Dream of the Goats).” Centered on a family Christmas gathering, the goats are, at first glance, a destructive force, storming the house and chewing through the couches. What the speaker quickly reveals, however, is that her gender presentation is the real source of disruption. As goats eat the ornaments, the speaker hears a voice in her ear,

“Androgyny went out in the ‘80s, when you were still young,” … I hoped it was the voice of the devil I didn’t know – a future lover perhaps, her flutes as piercing, her heart as cloven as any Pan I could ask for (and have).

But it was only my mother,

Here, the speaker exists in complex relation to Pan, the highly sexualized half-goat shepherd god who falls in love with a wood-nymph – she wishes for a lover like Pan, but she is also an androgynous figure, as per the mother’s accusation. Indeed, the mother goes on to directly compare the speaker to the goats, and to Pan by proxy, saying that

… “You’re starting to get whiskers, just like them.” Tender, the words went through me like a horn.

The speaker is clearly loved, and yet her gender manages to be as much of a disruption around the table as the goats eating the couch during the family Christmas party. Still, the speaker is deeply comfortable with her own illegibility, and this is reflected in the way that she welcomes the goats. The speaker is gentle with them, as they clear the table with cannibalistic revelry, consuming the goat stew. “Let them be goats,” she says. “Let them eat everything – / even the bones.”

In a collection preoccupied with history and consumed by loss – many of the poems center on hospitals or are preoccupied by aging and death – this incantation is ultimately what the speaker wishes for herself. She wants to consume everything, whether that means turning back time to learn the family recipes or to pursue a lost lover. Though they may appeal most to those struggling to find their place at the table, these are poems for anyone who wants to devour life, who is hungry and seeks to be filled.

0 notes

Photo

Prelude Books, $15.95

https://preludebooks.com/jason-koo/

By Allison Bird Treacy

Just weeks before John Ashbery’s death last fall; I took the holy journey from New York City to Hudson, NY where the ninety-year-old poet made his home. What I didn’t realize at the time was that I was stepping directly into the poetic lineage recounted in Brooklyn Poets founder Jason Koo’s third full-length collection More Than Mere Light (Prelude, 2018). A close examination of the New York School’s genealogy, Koo’s poetry has expanded the forms developed by Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, and others during the 1950s and 1960s and expanded it to fit his own experiences as an Asian-American man, a half-century removed.

One remarkable feature of More Than Mere Light is how it is uniquely structured around a few long poems, particularly “No Longer See,” a fifty page epistolary-like piece, and to a reader the form could easily intimidate. Koo’s everyday language, like that of his stylistic predecessors, however, readily welcomes the reader into the poem. Absorption into the text overshadows both the length and the examination of the New York School or trendy books, opening the poem at multiple levels.

The first lines of Koo’s long poem, “No Longer See,” drop each other into the “I do this, I do that” style characteristic of O’Hara’s poems – and with the immediacy common to most of the New York School and the poem helps us navigate with intermittent time stamps. He begins,

Somehow it’s 2:43 PM and ready I’ve frittered away most of my day. How are you? Banal question for a banal, as usual, Day. Every day for the past few weeks I’ve been thinking of starting This letter

Though little is happening in these first lines from a narrative perspective, that is precisely Koo’s point; his style is built upon the banal, on observations of the city he lives in and of daily life. And what poet – what person – doesn’t know deeply the procrastination these lines describe? Koo strikes to the heart of our modern lives by highlighting that wasted time, and as he continues, observes how this poem is a manipulation of his time. He wants to write a letter but also “to write poems, /and writing this letter meant writing prose, which/Would get in the way of those…” Then again, why shouldn’t more of our communication be in poem?

The idea that we can communicate in poem is too rare in our work, despite dedications, yet if we look backward it has a long lineage. Shakespeare, Yeats, and, yes, O’Hara, among many others, call count poems of address as part of their oeuvres. And for Koo, as for his literary predecessors, our daily lives are deserving of such artful observation, while the prose line is worthy of poetry’s linguistic and spatial invention. He plays with this form in “No Longer See,” with its variation on the traditional prose poem, as he writes about reading Jack Gilbert:

In the dark of the apartment, a seductive cool without the annoyance of mosquitoed toes. The muffled sweet moans Changed as she changed from what she was not into the more she was. Amazing sentence. The original enjambs after sweet Then not. You have to read that sentence again to catch all the nifty nuances I’ve put in there, as I’ve added my own enjambment To complicate things, things sweet then not, become a sweet knot.

Koo does not flinch at the pleasure of sound play, pushing it beyond common consonance or assonance and instead spilling homonyms and repetition into his reimagining of Gilbert into the prose of a letter. And, perhaps more amusingly, he puts a puzzle into the poem, and then points it out. Koo says, I dare you to go back and look at that again. Look at how much these common words can do when split and rearranged. The space of the poem, the stanza and the page, are an infinite playground.

To continue reading “No Longer See” is to dig deeper into the entanglement of the arts world – the cursory reading of trendy poets published by Wave Press (wonderful, but here read for the hipster street cred), the way Jackson Pollock’s work causes people to say ‘I could do that,’ a response also occasioned by work like this long poem-letter – but what about the rest of More Than Mere Light? The title, shared with the first poem and taken from Karl Ove Knausgaard, welcomes us into the book:

The day always came with more than mere light, came hugely pawing through the windows, Frisking you up, no soft fortress of pillows cobbled around your head could help you. The sunlight in silence pouring down, insidiously weighted With all the expectations of the city, the street cleaners moving through Unearthing groggy zombies parking in pajamas, The drilling beginning, men tucked inside the scaffolding on the brownstone next door

Koo firmly roots his poems in New York City, particularly in Brooklyn, yet the idea that “The day always came with more than mere light” has broader implications. It comes with obligations and exhaustion, no matter how we push back against the, yet also with wonder if we pay attention. Notice, for example, how the annoyance of drilling also comes with the peculiar phrasing “men tucked inside the scaffolding,” so that the reader cannot help but imagine a miniature, urban dollhouse, the tiny figures posed on the ledges and in hidden crevices. This small change of perspective, here a plain verb made strange, transforms the ordinary.

Too often, we embed ourselves in one of two camps: constant boredom or persistent wonder, or in modern parlance, everything is either #fml or #blessed. But it doesn’t have to be one or the other, and we can find more pleasure and more play in that in between space, where there’s breathing room. After all –

Maybe stabbing is what the fire needs, not water, Maybe stabbing is what the self needs, not water, not mere light, holes to create some breathing, As when a child traps some caterpillars in a jar and punctures holes over the foil sealing its opening

And next morning fresh caterpillars have bloomed all over mom’s curtains.

When was the last time you looked between the buildings and room to grow, found more than just mere light filtering through? As he records quotidian New York scenes, Jason Koo pauses over those remarkable moments, lets them stand alongside the complaints and consumerism, the competition and social climbing. Here, surprises appear in all their strange glory, like caterpillars on the curtains, perhaps unwelcome and yet wondrous all at once

#jason koo#brooklyn poets#poetry review#new york school#new york city poets#new poetry books#Poetry Book Reviews

0 notes

Photo

Glass Lyre Press, $16 https://glass-lyre-press.myshopify.com/collections/full-length-collections-1/products/walking-toward-cranes

by Allison Bird Treacy

In her classic text, Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag tells us, “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place." But when we hold out that lesser identification, what happens? What lives in the kingdom of the sick?

As it turns out, many things reside there. In her second full-length collection, Walking Toward Cranes (Glass Lyre Press, 2016), Amy Small-McKinney invokes the borders of the tumor, cancer carrying its own passport as she opens for the reader the experience of dwelling within the territory claimed by breast cancer.

The second poem in Walking Toward Cranes, “Flying Low,” offers the reader an overview of the territory Small-McKinney will traverse. Settled within the speaker’s line of vision sits the question,

What are those birds called that flew in front of my car,

black dots, floaters in an eye? Near my home, I was driving home,

When a swarm flew so low I almost hit them

…

Inside of me, there is a swarm, surplus only heat will destroy.

Unnamed, the swarm moves from the outside to the inside, from threat that can put a car on a collision course to one that can irradiate life at its very core. Small-McKinney’s language is sparse, tight; it holds the swarm’s formation as it wends its way down the page. This is the nature of the writing throughout as Small-McKinney unburdens herself of unnecessary flourishes. As the “misshapen breast tattooed for surgical precision,” (“The Matter of Beginning”), these poems reach the reader with that same accuracy, an artistic exactitude.

Small-McKinney divides her text into three parts: Treatment, The Healing, and Walking Toward Cranes, and while Treatment is interested in the kingdom of the sick, The Healing struggles with reentry into a more everyday life. In fact, the process is so decidedly foreign that it becomes a new experience entirely. As Small-McKinney describes in the poem “Entry,”

we are not maps, nothing leads us to each other. I shake each hand, talk about weather. Accept the fig the housekeeper places in front of me, black coffee, the future.

There is no clear, mapped path, but there can be simple instruction for this unexpected new beginning. The future is bittersweet, it is the fig and the black coffee both, and it is all open-handed acceptance. This is what knowing does to a person, as in “Peacock, Home.” Here, the speaker says of the peacock:

In spite of its beauty, I am afraid it will become cruel.

This has happened before, to beauty.

It has happened before, it will happen again. Amy Small-McKinney shows us that, despite all this, we can walk forward, towards cranes and what is new, into loss that isn’t an ending but the border of a new country.

#amy small mckinney#walking toward cranes#2016 Kithara Prize#glass lyre press#poetry books#poetry reveiw

0 notes