#all the best character actors (the only right style of actor for marlowe) are in their 50s now

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Who's currently on your list of actors you would cast as Marlowe (and is Shea on there)?

Shea is of course on my list, but I would only cast him as Marlowe in the absolute most tender adaptation possible. In the same way that Bogart's little man energy brings an air of vulnerability and softness to the role, so too would Shea, and it would be important to capitalize on that as much as possible. Little man, subtext king, soft prince of my heart, it would be a waste to have him play the non-chandlerian tough guy conception of Marlowe.

Meanwhile, when I re-read the books, I do still imagine basically White Collar era Tim Dekay. He's too old for it now (though tbh Shea is also too old for it! Marlowe is 42 in The Long Goodbye!!), but he has a perfect blend of tall, square jaw american masculinity and weathered, scrunchy-mouth soft sadness that is so right for Marlowe, for me. Handsome but not pretty, physically big but very capable of being punched. He's my special marlowe man and I hold him in my heart and imagination always.

it's hard because where are my slightly weathered american men in hollywood these days? u know? everyone is so pretty these days. we are missing a whole demographic of american character actor. this would be a lot easier ten years ago

Others I turn around in my head include, without explanation: toby stephens, noah segan, steven yeun, sterling k. brown, logan marshall-green

idk dude it's hard and getting harder all the time! who's on your list?

#philip marlowe#all the best character actors (the only right style of actor for marlowe) are in their 50s now#and I need some 40s character men#where are they#guys in their 30s look like babies#also there are no slightly un-handsome guys in their 30s in hollywood these days#it's killer

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

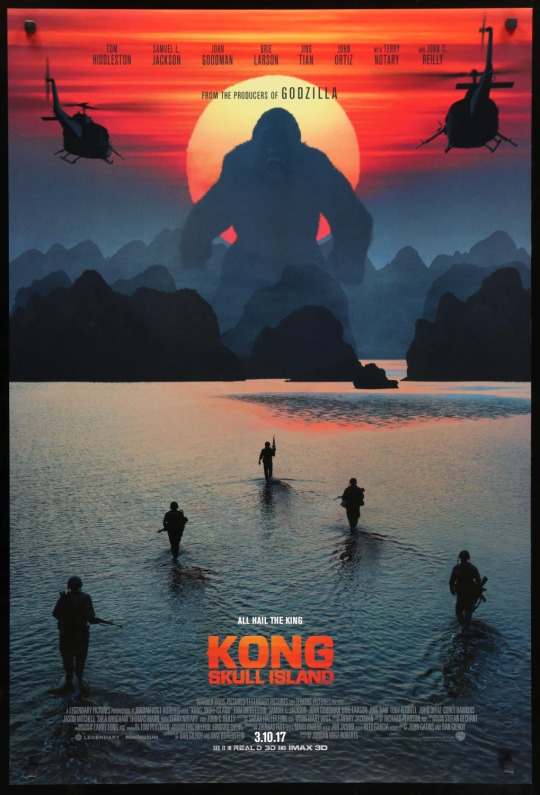

The Road To “Godzilla VS. Kong”, Day Four

(Sorry for the delay on this one, Life proved just a bit too busy the other day to finish it; my “Godzilla: King of the Monsters” review is gonna be pushed back as a result too. But! No worries, on we go. ^_^)

KONG: SKULL ISLAND (2017

Director: Jordan Vogt-Roberts

Writers: Dan Gilroy, Max Borenstein, Derek Connolly, John Gatins

Starring: Samuel L. Jackson, Tom Hiddleston, Brie Larson, John Goodman, John C. Reilly

youtube

Technically speaking, Gareth Edwards’ “Godzila” from 2014 was the first entry in what is now generally referred to as “The Monsterverse”, an attempt by Warner Bros. Studios and Legendary Pictures to do a Marvel Studios-style series of various interconnected movies (and which, like most such attempts to cash in on that particular trend, hasn’t really panned out; “Godzilla VS. Kong” seems likely to be its grand finale as far as movies are concerned, the only two “names” it had going for it are Godzilla and Kong themselves, and even at its most successful it was never exactly a Powerhouse Franchise). But the thing is, when that movie was made, the idea of a “Monsterverse” did not yet exist; it was only well after the fact that Legendary and Warner Bros. got the idea to turn a new “Kong” project into the building block of a Shared Universe of their own that they could connect with the 2014 “Godzilla”, with a clear eye on getting to remake one of the most singularly iconic (and profitable) Giant Monster Movies of all time. As you might guess from that description, however, said “Kong” project also had not originally been intended for such a purpose; it would not be until 2016 that it would be retooled from its original purpose (a prequel to the original “King Kong” titled simply “Skull Island”) into its present form, which goes out of its way to reference Monarch, the monster-tracking Science organization seen over in 2014’s “Godzilla” and which includes a very obviously Marvel-inspired post-credits stinger explicitly tying Kong and Godzilla’s existences together.

The resulting film is fun enough, all things told, but that graft is also really, distractingly obvious.

Honestly, I wish I knew why I’m not, generally, fonder of “Skull Island” than I am. It’s not as if, taken as a whole, it does anything especially bad; indeed it does a great deal that is actively good. Consider, for example, the rather unique choice to make it a Period Piece; that’s decently rare for a Monster Movie as it is (indeed one of the only other examples that springs to mind for me is Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake of “King Kong”, which chose to retain the original’s 1933 setting), and it’s rarer still that the era it chooses to inhabit is an immediately-post-Vietnam 1970’s. Aesthetically speaking, the movie takes a decent amount of fairly-obvious influence from that most classic of Vietnam-era films, “Apocalypse Now” (a fact that director Jordan Vogt-Roberts was always fairly open about), and it results in some of the movie’s strongest overall imagery (in particular a shot of Kong, cast in stark silhouette, standing against the burning sun on the horizon with a fleet of helicopters approaching him, one of a surprisingly small number of times the movie plays with visual scale to quite the same degree or with quite the same success as “Godzilla” 2014). It also means the movie is decked out in warm, lush colors that really do bring out all the personality of its Jungle setting in the most compelling way and, given how important the setting is to the film as a whole, that proves key; Skull Island maybe doesn’t become a character in its own right the way the best settings should (too much of our time is spent in fairly indistinct forests especially), but it does manage to feel exciting and unusual in the right ways more often than not. The “Apocalypse Now” influence also extends to our human cast, which is sizeable enough here (in terms of major characters we need to pay attention to played by notable actors, “Skull Island” dwarfs “Godzilla” 2014 by a significant margin) that the framework it provides-a mismatched group defined by various interpersonal/intergenerational tensions trying to make their way through an inhospitable wilderness, ostensibly in search of a lost comrade-is decently necessary. Though here we already run into one of those aspects of “Skull Island” that doesn’t quite land for me. Taken as a whole, it sure feels like the human characters here should be decently interesting; certainly, our leads are all much better defined and more engagingly performed than Ford Brody, to draw the most immediately obvious point of comparison. Brie Larson (as journalistic Anti-War photographer Mason Weaver), Tom Hiddleston (as former British Army officer turned Gun For Hire James Conrad), and John C. Reilly (as Hank Marlow, a World War II soldier stranded on Skull Island years ago) definitely turn in decently strong performances; I wouldn’t call it Career Best work for any of them (Hiddleston especially feels like he’s on auto-pilot half the time, while Larson has to struggle mightily against how little the script actually gives her to work with when you stop and look at it) but they at least prove decently enjoyable to watch (Reilly especially does a solid job of making his character funny without quite pushing him over the edge into Total Cartoon Territory). I likewise feel like Samuel L. Jackson’s Preston Packard has the potential to be a genuinely-great character; his lingering resentment at the way the Vietnam War played out and the way that feeds into his determination to find and defeat Kong is, again, a clever and compelling use of the 70’s period setting, it gives us a good, believable motivation with a clear and strong Arc to it, and Jackson does a really solid job of playing his Anger as genuine and poignant rather than simply petulant or crazed. But there’s just too much chaff amongst the wheat, too much time and energy devoted to characters and ideas that don’t have any real pay-off. This feels especially true of John Goodman’s Bill Randa, the Monarch scientist who arranges the whole expedition; the Monarch stuff in general mostly feels out of place, but Randa in particular gets all of these little notes and beats that seem meant to go somewhere and then just kind of don’t. Which is kind of what happens with most of the characters in the movie, is the thing; we spend a lot of screen-time dwelling on certain aspects of their backstories or personalities, and then those things effectively stop mattering at all after a certain point, even Packard’s motivations. A Weak Human Element was one of the problems in “Godzilla” 2014 as well, though, and you’ll recall I quite liked that movie. There, though, the human stuff was honestly only ever important for how it fed into the monster stuff; it was the connective tissue meant to get us from sequence to sequence and not much more. Here, though, it forms the heart and soul of the story, and that means its deficiencies feel a lot more harmful to the whole.

Still, those deficiencies really aren’t that severe, and moreover, like I was saying before, there’s a lot about “Skull Island” to actively enjoy. The Monsters themselves do remain the central draw, after all, and for the most part the movie does a solid job with that aspect of things. It does not, perhaps, recreate “Godzilla” 2014’s attempt to make believable animals out of them (even as it does design most of them with even more obvious, overt Real World Animal elements), but there is a certain playful energy that informs them at a conceptual level that I appreciate. Buffalos with horns that look like giant logs with huge strands of moss and grass hanging off their edges, spiders whose legs are adapted to look like tree trunks, stick bugs so big that their camouflage makes them look like fallen trees…the designs feel physically plausible (especially thanks to some strong effects work that makes them feel well inserted into the real environments), but there’s a slightly-humorous tilt to a lot of them that I appreciate, especially since it never outright winks at the audience in a way that would undercut the stakes of the story. Kong too is very well done; rather than the heavily realistic approach taken by the Peter Jackson version from 2005, this Kong is instead very much ape-like but also very clearly his own creature (in particular he stands fully erect most of the time), with a strong sense of Personality to him as well; some of the best parts of the movie are those times where we simply peek in on Kong simply living his life, even when that life is one that is, by nature, violent and dangerous. Less successful, sadly, are his nemeses, the Skullcrawlers; very much like “Godzilla” 2014, Kong is here envisioned as a Natural Protection against a potentially-dangerous species that threatens humanity (or in this case the Iwi Tribe who live on Skull Island, but we’ll talk more about them later), and while they’re hardly bad designs (the way their snake-like lower bodies give them a lot of neat tricks to play against their enemies in battle are genuinely fun in the right sort of Scary Way), they’re also pretty bland and forgettable, even compared to the MUTOS. That said, they serve their purpose well enough, and their big Action Scene showdowns with Kong are genuinely solid. Indeed, the movie’s big climactic brawl between Kong and the biggest of the Skullcrawlers has a lot of good pulpy energy to it (particularly with how Kong winds up using various tools picked up from all around the battlefield to give himself an edge), likewise there’s a certain Wild Fun to the sequence where our hapless humans have to try and survive a trek through the Crawlers’ home-turf.

Where things get a bit tricky again is when the movie attempts to put its own spin on “Godzilla”’s conception of its monsters as part of their own kind of unique ancient eco-system. The sense of Grandeur that gave a lot of that aspect such weight there is mostly absent here, especially; there are instances where some of that feeling comes through (Kong’s interactions with some of the non-Crawler species, for example, do a good job giving us an endearing sense of how Kong fits into this world), but far more often it treats the monsters as Big Set-Piece Attractions. Which is fine as far as it goes, it just also means a lot of them aren’t as memorable or impactful as I might like. Meanwhile, the way the Iwis have built their home to accommodate, interact with, and protect themselves from the island’s bestiary feels like a well-designed concept that manages to suggest a lot of History without having to spell it out for us in a way that I appreciated (I would also be inclined to apply this to the very neat multi-layered stone-art used to portray Kong and the Crawlers except that the sequence where we see them is the most overt “let’s stop and do some world-building” exposition dump in the whole movie). But the Iwis in general are one of the more difficult elements of the movie to process, too; it seems really clear there was a deliberate effort here to avoid the most grossly racist stuff that has been present in prior attempts to portray the Natives of Skull Island, and as far as it goes I do think those efforts bear some fruit; we are, at the very least, very far away from the Scary Ooga-Booga tone of, say, “King Kong VS. Godzilla”, and that feels like it counts for something. I just also feel like there’s some dehumanizing touches to their portrayal (in particular they never speak; I don’t mean to imply that Not Speaking equals Inhuman, but the fact that we are not made privy to how exactly they do communicate means we’re very much kept at arm’s length from them in a way that seems at least somewhat meant to alienate us from them), especially given their role in the story as a whole is relatively minor.

At the end of the day, though, all the movie’s elements, good and bad, don’t really feel like they add up together coherently enough to make an impact. And I think if I had to try and guess why, even as I find it wholly enjoyable with a lot to genuinely recommend it by, I don’t find myself especially enamored by “Skull Island”. It has a lot of different ideas of how to approach its story-70’s pastiche, worldbuilding exercise, Monster Mash-but doesn’t seem to quite succeed at realizing any of them fully, indeed often allowing them to get in each other’s ways. It isn’t, again, a bad movie as a result of that; there really isn’t any stretch of it where I found myself bored or particularly unentertained. But I did paradoxically find myself frequently wanting more, even as by rights the movie delivers on basically what I was looking for from it.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tenet

If someone tells you they got Tenet the first time, they’re probably lying.

As this is a spoiler-free review, in line with the marketing I won’t be discussing plot details. Suffice to say Christopher Nolan’s latest, starring John David Washington, Robert Pattinson and Elizabeth Debicki, is a sci-fi neo-noir heist thriller which begs questions of our understanding of time.

Nolan’s features offer that rare conflation of the frenetic and contemplative; grand ideas someone like Malick gives you time to reflect on while his contemporary lends you pause only once the months, or maybe days arrive between your intendedly first and here inevitably second viewing. The whole conception propels a phrenic overload tied not, at least at the time of viewing, to purely philosophical musings but the welcome sensory realisation that you are amidst something most viewers (this author included) will not immediately reckon with and enjoy teasing out with the friends, as we did, for at least the immediate hour following and no doubt many more.

Inception alarm bells may be ringing in many heads; a straightforward point of comparison, they are very different. The former remaining a predominantly speculative piece of fiction, Tenet, while more labyrinthine, importantly, and this author is willing to revise this opinion on repeat viewings, offers fewer interpretations, for this is in every sense a noir.

The exception to this rule are the motivations of characters, or a character, as your reading may have it, who while hugely consequential in events do/does not appear on screen; an eerie, thrilling story innovation likely to engender the deepest dives into this mythology.

Progressing with the pace and stylings of a Chandler novel, the tighter frames and shadows that befitted those centred in Nolan’s breakout Memento, absent here, better set the tone for a tumble down a rabbit hole. Unlike the Big Sleeps, Chinatowns and best of the genre, in Tenet our cast of characters by and large are evidently assembled relatively early (things were fine, given the premise, when mysterious strangers passed in the night), by which time the noir imprint overstays its welcome and we all fall into large-scale action fare that barely begets Marlowe or his ilk.

And the action is good; very good. A car chase, a later raid, hanger antics, an ‘abseil’ and a mesmerising third act among highlights, the particular premise (and there are too shades of The Matrix here) proffers us something we’ve barely or ever gotten to see alongside such significantly practical production values. The buy-in will not be unfamiliar to say Star Trek or Doctor Who fans who will easily pinpoint familiar stories and arcs, but Nolan, overly interested in the practical applications and furnished with many bags of money, here possesses a much bigger canvas to play.

Deserving of attention to detail as regards the layers and intricate set pieces necessary to this action, these sequences are better for, as Nolan is want, their having actually been filmed; with the intrusions of CGI emerging overly obvious and grating. The only other appearance that takes us out of this universe is Michael Caine. As good as it is to see him, Caine’s about one step up from phoning it in and Nolan should have known by now to throw out his checklist.

Spectacular for its plot, staging and that visual which the premise atypically permits, conversely lacking and glaringly so is that otherwise so essential; character. Thankfully absent the need for spoilers I will tell you everything one could glean about every character in the next paragraph.

Washington’s Protagonist (that’s what they call him) has a sense of honour, wants to do the right thing and save the innocent. He’s none too au fait with high society types, but that’s quickly forgotten. Debicki’s Kat, admirably and statedly, will do anything for her son. Pattinson’s Neil, well, he’s a physicist, and nifty with a bungee cord. There is one other character whose casting is treated as a reveal and even as it’s a very lax one I won’t ruin it here. They are by far the most interesting figure, their motivations being mired in the desperation and uncertainty characteristic of late Soviet-era Russia, though that compelling falls away with the likes of his hammy invective lifted directly from Casino Royale’s Le Chiffre.

It doesn’t help that the actor is very bad at playing this sinister figure; their casting only further undermined by a lousy Russian accent they too deployed to ill-effect as a villain in a film this author had graciously forgotten to this point. Debicki saves a lot of their shared sequences; her performance and physical presence here-in lending Tenet much of the gravitas not suggested by Kat’s undercooked characterisation.

The figure opposite Kat being evidently intended to reflect the struggle of the film, there is a conflict in Tenet, a thrilling one, philosophically and present in any decision characters make, between fatalism and nihilism. For they are different things, positing question of action versus reaction and the value of morality itself in the face of its very absence should doom impend. It’s a crucial distinction the movie and those in the firing lines largely acknowledge and use to account for their choices; too inevitably reflective of the divergent readings to come. It all could have played out to such greater heights with a more empathetic, nuanced foil that might have been had he not, say, threatened to feed someone their testicles.

Amidst a long delay and notwithstanding any detractions Tenet was well worth the wait; Nolan gave us something we were excited for and even better left us with something we’re thrilled to see again.

Tenet is in cinemas from August 27

#xl#reviews#tenet#christopher nolan#elizabeth debicki#john david washington#michael caine#robert pattinson

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Long Goodbye is by now an acknowledged classic. It wasn’t always so. As Pauline Kael writes in her 1973 review, ‘It’s a knockout of a movie that has taken eight months to arrive in New York because after being badly reviewed in Los Angeles last March and after being badly received (perfect irony) it folded out of town. It’s probably the best American movie ever made that almost didn’t open in New York.’ Charles Champlin, one of the initial culprits, titled his review ‘A Private Eye’s Honour Blackened’. But as early as 1974, Stewart Garrett in Film Quarterly was already underlining its importance and influence: ‘‘the masterwork of America’s most interesting working director….In watching Chinatown, one can feel The Long Goodbye lurking behind it with the latent force of a foregone conclusion’. All I want to do here is add my praise, point to a couple of aspects of the film’s particular brilliance, and also indicate some problems with the film that its biggest fans have been too quick to gloss over.

The movie begins and ends with an extract from the song ‘Hooray for Hollywood’, a nod to dreamland and part of the film’s homage to noir and the detective genre. Elliot Gould is a different Marlowe than Humphrey Bogart, looser, gentler, even more addicted to tobacco, with cigarettes constantly dangling from his thick, sensuous lips. The car he drives, the apartment building he lives in, the bars he frequents, all conjure up the forties. But the LA he moves through, a character of its own in this film (the skyline, the highways, the all-night supermarkets, Malibu), with the women in the apartment next door making hash brownies, practicing yoga, and dancing topless, all point to the film’s present. And that interplay between past and present, figured through the casting of Elliot Gould as the central character, is one of joys of the film.

Gould’s Marlow, unkempt, seeming to offer a wry, disbelieving and humours look at everything he sees, is convincingly single, marginal, and over-reliant on his cat for company. He is the most unkempt and bedraggled of leading man: loose, irreverent but convincingly embodying someone who carries the night with him like a halo; a knight errant reeking of stale tobacco, too much booze and too little sleep. His friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouten) calls hims a born loser.

David Thomson writes of how Altman ‘spends the whole film concentrating on the way Elliott Gould moves, murmurs, sighs, and allows silence or stillness to prevail’. And this at a time when as Pauline Kael writes in her review of the film, by 1973 , ‘Audiences may have felt that they’d already had it with Elliot Gould; the young men who looked like him in 1971 have got cleaned up and barbered and turned into Mark Spitz. But it actually adds poignancy to the film that Gould himself is already an anachronism…Gould comes back with his best performance yet. It’s his movie.’ It certainly is. Next to M*A*S*H and Bob &Carol&Ted&Alice, it’s also become the one he’s most associated with.

The first few scenes in the film dazzle. The whole sequence with the cat at the beginning where Marlowe gets up to feed it, the cat jumping from counter, to fridge, and onto Marlowe’s shoulder is disarming and rather wondrous. Even those who don’t love cats will be charmed. But the scene also conveys quite a bit about who Marlowe is: someone lonely, who relies on cats for company; someone responsible and loving who cares that the cat is well fed and willing to go out in the middle of the night to buy the cat’s preferred brand; a good neighbour too, prepared to get the brownie mix the women next door ask for and unwilling to charge them for it: a gent or a chump? The choices Altman makes to show and tell us the story are constantly surprising, witty and wondrous on their own. See above, a minor example, that begins inside the apartment, showing us the city’s skyline, then the women, then the women in the city, before dollying down, something that looks like a peek at a little leg action before showing us, perfectly framed, Marlowe arriving in his vintage car.

In The Long Goodbye much is filmed through windows, which sometimes look onto something else, allowing action to happen on at least two planes. However the dominant use of this is to show the play of what’s happening between foreground and background, with the pane of glass, allowing partial sight of what’s beyond the glass and the reflection itself only partially showing what’s in front of it; and both together still only adding up to two partial views that don’t make a whole but which suggest there’s a background to things, and things themselves are but pale reflections of a greater underlying reality. You can see an example of this in the still above, from the the interrogation scene at the police station with the two way mirror. It’s a beautiful, expressive composition. According to Richard K. Ferncase, ‘the photography by Vilmos Zsigmond is unlike the heavy chiaroscuro of traditional noir’. However, as evident in the still above, whilst it might be unlike, it certainly nods to and references it. In fact it’s part of a series of references: the gatekeeper who does imitations of James Stewart, Walter Brennan, Barbara Stanwyck etc; the way Marlowe lights matches a la Walter Neff, the hospital scene where it seems like the Invisible Man or Bogart before his plastic surgery in Dark Passage, etc.

This must be one of Vilmos Zsigmond’s greatest achievements as a cinematographer. Garret writes of how, ‘Altman accentuated the smog-drenched haze of his landscape by slightly overexposing, or ‘fogging’ the entire print.’ Ferncase admires the ‘diaphanous ozone of pastel hues, blue shadowns, and highlights of shimmering gossamer’ Zsigmond created by post-flashing the film. Zsigmond himself attributes this to a low budget: ‘We…flashed the film heavily, even more than we flashed it on McCabe. And the reason was basically because we didn’t have a big budget there for big lights and all that. So we were really very creative about how, with the little amount of equipment that we had, how we are going to do a movie in a professional way. A couple of things we invented on that movie — like flashing fifty per cent, which is way over the top. But by doing that we didn’t have to hardly use any lights when go from outside or inside and go outside again.’.

Robert Reed Altman notes how, ‘On Long Goodbye the camera never stopped moving. The minute the dolly stopped the camera started zooming. At the end of the zoom it would dolly and then it would zoom again, and it just kept moving. Why did he do it? Just to give the story a felling, a mood, to keep the audience an an edge’. Zsigmond describes how this came to be, ”On Images, when we wanted to have something strange going on, because the woman is crazy, we decided to do this thing — zooming and moving sideways. And zooming, and dollying sideways. Or zooming forward. What is missing? Up and down! So we had to be able to go up and down, dolly sideways, back and forth, and zoom in and out. Then we made The Long Goodbye and Robert said, ‘Remember that scene we shot in Images? Let’s shoot this movie all that way’.

They did. But it’s worth remarking that whilst Altman was happy to let actors improvise and to grab and use anything useful or interesting that happened to pass by the camera’s path (the funeral procession, the dogs fucking in Mexico, etc.), the use of the camera seems to me to be highly conscious and controlled. See the scene below when Marlowe brings Roger Wade (a magnificent Sterling Hayden, like wounded lion on its last legs) home to his wife.

In the scene above Marlowe has just brought Wade back home to his wife Eileen (Nina van Pallandt), who’d hired Marlowe to do just that. As Marlowe heads to the beach, note how they’re both filmed outside a window, Wade cornered into the left side of the frame, his wife on the right; the palm trees reflected on the glass but outside. Inside the house is dark, the conversation pointed. In the next shot we get closer to Wade but stil framed within frames, encased in his situation, with window shades acting like bars behind him. In the third shot, we get closer to where the first shot was but Wade seems even murkier, hidden. When Eileen says ‘milk, is that what you really want,’ The camera zooms in, first on him, then her, then him, and as he walks over to her, we see Marlow behind a second window in the back. So we are seeing a domestic scene through a window, sunny California reflected in the palms in front, in the surf behind, something dark happening inside the house, and Marlow, pondering outside, for the moment their plaything, and playing on the surf behind, seen through two sets of glass. Much of the scene will be played like that until Wade goes to join Marlowe outside. Brilliantly evocative images, vey expressive of the characters, their situation and their dynamic, and they seem to me to be perfectly controlled to express just that. In fact that series of images evoke what the film’s about (see below)

The scene where the Wades and Marlowe are gathered together for the first time, rhymes with their last one. This time it’s Marlowe and Eileen who talk, and the discussion is on the husband, who as the camera zooms past Eileen and Marlowe’s conversation, and through the window, we see heading fully dressed to the ocean. The camera cuts to them from the outside, once more seeing through a window, but the darkness is on the outside now, and we don’t hear what they’re saying. What we hear now is the darkness, and what we see, clearly and without mediation is Wade letting the surf engulf him. It’s a perfect riposte to the first scene, taking elements of the same style, but accenting different ones, and creating a series of images that remain beautiful and startling in themselves but beautifully express what’s going on, what’s led to this. Had I extended the scene longer, you’d be able to see Eileen and Marlow also engulfed by the sea, the Doberman prancing by the shore, and that indelible image of the dog returning only with Wade’s walking stick. It’s great.

Schwarzenegger makes an uncredited appearance in The Long Goodbye, screaming for attention by flexing his tits, and looking considerably shorter than Elliot Gould. An interesting contrast between a characteristic leading man of the 70s and how what that represents gave way to Schwarzenegger’s dominance in the 80s and 90s, and what that in turn came to represent. But though this is a fun moment in the film, its also what I liked least about it: i.e. the stunt casting. Nina van Pallandt is beautiful and she’s ok. But think of what Faye Dunaway might have brought to the role. Director Mark Rydell as gangster Marty Augustine is also ok but imagine Joe Pesci. As to Jim Bouton, a former ballplayer and TV presenter as Terry Lennox, to say that he’s wooden is to praise too highly. There’s a place in in cinema for this type of casting– and a history of much success — but see what a talented pro like David Carradine brings to the prison scene — not to mention Sterling Hayden and Elliot Gould both so great — and imagine the dimensions skilled and talented actors might have brought to the movie The Long Goodbye is great in spite of, not because of, the casting of these small but important roles.

José Arroyo

The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, USA, 1973) The Long Goodbye is by now an acknowledged classic. It wasn't always so. As Pauline Kael writes in her 1973 review, 'It's a knockout of a movie that has taken eight months to arrive in New York because after being badly reviewed in Los Angeles last March and after being badly received (perfect irony) it folded out of town.

#Bogart#David Carradine#Elliot Gould#James Stewart#Jim Bouton#Mark Rydell#Marlowe#Nina Van Pallandt#noir#Pauline Kael#the detective genre#The Long Goodbye#Vilmos Zsigmond

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rider

Rider Insurance Motorcycle

Rider The App

Rider Furniture. 'Voted Best Independently Owned and Operated Furniture Store in Central New Jersey' is a family owned business located in Kingston, NJ (Just north of Princeton). We have one of central New Jersey’s largest selections of quality manufacturers, styles, finishes and fabrics always at discounted prices. Rider also offers insurance for scooters and mopeds, ATVs, UTVs & Off-road vehicles, off-road and trail motorcycles, and dirt bikes. Rider Exists to Serve the Motorcycle Community In addition to offering low cost motorcycle insurance coverage, Rider is proud to serve the greater motorcycle community.

The RiderDirected byChloé ZhaoProduced by

Chloé Zhao

Mollye Asher

Bert Hamelinck

Sacha Ben Harroche

Written byChloé ZhaoStarring

Brady Jandreau

Lilly Jandreau

Tim Jandreau

Lane Scott

Cat Clifford

Music byNathan HalpernCinematographyJoshua James RichardsEdited byAlex O'FlinnDistributed bySony Pictures Classics

Release date

May 20, 2017 (Cannes)

April 13, 2018 (United States)

105 minutesCountryUnited StatesLanguageEnglishBox office$4.2 million[1]

The Rider is a 2017 American contemporary westerndrama film written, produced and directed by Chloé Zhao. The film stars Brady Jandreau, Lilly Jandreau, Tim Jandreau, Lane Scott, and Cat Clifford and was shot in the Badlands of South Dakota. It premiered in the Directors' Fortnight section at the Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2017,[2][3] where it won the Art Cinema Award.[4] It was released in theaters in the United States on April 13, 2018. It grossed $4.2 million dollars, making it a small commercial success. The film was critically praised for its story, performances, and its depiction of the people and events that influenced the film.

Plot[edit]

All of the characters are Lakota Sioux of the Pine Ridge Reservation.[5] Brady lives in poverty with his father Wayne and his autistic teenaged sister, Lilly. Once a rising rodeo star, Brady suffered brain damage from a rodeo accident, weakening his right hand and leaving him prone to seizures. Doctors have told him that riding will make them worse.

Brady regularly visits his friend, Lane, who lives in a care facility after suffering brain damage from a similar accident. Brady's father does little for the family, spending their income on drinking and gambling. Once, to fund their trailer, he sells their horse, Gus, infuriating Brady.

Brady takes a job in a local convenience store to raise money for the family. He also makes some money breaking in horses. With his savings, he intends to buy another horse, specifically a temperamental horse named Apollo, but his father actually buys it for him and Brady bonds with it, as he had with Gus. However, his riding and refusal to rest cause him to have a near-fatal seizure. Doctors warn him that more riding could be fatal. Upon returning home, Brady finds that his horse has had an accident, permanently injuring a leg. Knowing that the horse will never be able to be ridden ever again, and not being able to bring himself to put his own horse down, he must have his father to do it for him.

After an argument with his father, Brady decides to take part in a rodeo competition, despite the doctors' warnings. At the competition, just before he competes, he sees his family watching him. He finally decides to walk away from the competition and life as a rodeo rider.

Cast[edit]

Brady Jandreau as Brady Blackburn

Tim Jandreau as Wayne Blackburn

Lilly Jandreau as Lilly Blackburn

Cat Clifford as Cat Clifford

Terri Dawn Pourier as Terri Dawn Pourier

Lane Scott as Lane Scott

Tanner Langdeau as Tanner Langdeau

James Calhoon as James Calhoon

Release[edit]

Rider Insurance Motorcycle

Sony Pictures Classics acquired the distribution rights in the U.S. and other territories two days following its premiere at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival.[6]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

The Rider grossed $2.4 million in the United States and Canada, and $1.1 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $3.5 million.[1]

Critical response[edit]

On review aggregatorRotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 97% based on 182 reviews, and an average rating of 8.44/10. The website's critical consensus reads, 'The Rider's hard-hitting drama is only made more effective through writer-director Chloé Zhao's use of untrained actors to tell the movie's fact-based tale.'[7] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 92 out of 100, based on 42 critics, indicating 'universal acclaim'.[8]

Godfrey Cheshire of RogerEbert.com gave the film 4 out of 4 stars, writing that its 'style, its sense of light and landscape and mood, simultaneously give it the mesmerizing force of the most confident cinematic poetry.'[9]

Former United States President Barack Obama listed The Rider among his favorite films of 2018, in his annual list of favorite films.[10]

Top ten lists[edit]

The Rider was listed on numerous critics' top ten lists for 2018.[11]

1st – Michael Phillips, Chicago Tribune

1st – Alison Willmore, BuzzFeed

1st – Randy Myers, San Jose Mercury News

1st – Peter Debruge, Variety

2nd – Godfrey Cheshire, RogerEbert.com

3rd – Stephen Farber, The Hollywood Reporter

3rd – Owen Gleiberman, Variety

3rd – Ann Hornaday, The Washington Post

4th – David Edelstein, New York Magazine

4th – Nick Schager, Esquire

5th – Matt Singer, ScreenCrush

6th – Seongyong Cho & Sheila O'Malley, RogerEbert.com

6th – Emily Yoshida, New York Magazine

6th – Marlow Stern, The Daily Beast

7th – Jake Coyle, Associated Press

7th – David Fear, Rolling Stone

7th – Todd McCarthy, The Hollywood Reporter

7th – Justin Chang, Los Angeles Times

7th – Nicholas Barber, BBC

8th – Donald Clarke & Tara Brady, The Irish Times

8th – Scott Tobias, Filmspotting

9th – Christopher Orr, The Atlantic

10th – Philip Martin, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette

10th – Sara Stewart, New York Post

Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Gary Thompson, Philadelphia Daily News

Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Moira Macdonald, Seattle Times

Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – James Verniere, Boston Herald

Best of 2018 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Gary M. Kramer, Salon.com

Best of 2018 (listed alphabetically, not ranked), NPR

Best of 2018 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Ty Burr, The Boston Globe

Accolades[edit]

AwardDate of ceremonyCategoryRecipient(s) and nominee(s)ResultRef(s)Film Independent Spirit AwardsMarch 3, 2018Best FeatureMollye Asher, Sacha Ben Harroche, Bert Hamelinck and Chloé ZhaoNominated[12]Best DirectorChloé ZhaoNominatedBest EditingAlex O'FlinnNominatedBest CinematographyJoshua James RichardsNominatedGotham Independent Film AwardNovember 26, 2018Best FeatureThe RiderWon[13][14]Audience AwardThe RiderNominatedBritish Independent Film AwardsDecember 8, 2018Best Foreign Independent FilmChloé Zhao, Mollye Asher, Sacha Ben Harroche and Bert HamelinckNominated[15]National Board of ReviewJanuary 8, 2019Top Ten Independent FilmsThe RiderWon[16]National Society of Film CriticsJanuary 5, 2019Best PictureThe RiderWon[17]Best DirectorChloe ZhaoNominated

References[edit]

^ ab'The Rider (2018) - Financial Information'. The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

^'Fortnight 2017: The 49th Directors' Fortnight Selection'. Quinzaine des Réalisateurs. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

^Keslassy, Elsa (April 19, 2016). 'Cannes: Juliette Binoche-Gerard Depardieu Drama to Kick Off Directors Fortnight'. Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

^Hopewell, John (May 26, 2017). 'Cannes: Chloe Zhao's 'The Rider' Tops Cannes' Directors' Fortnight'. Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

^Cheshire, Godfrey. 'The Rider movie review'. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

^Setoodeh, Ramin (May 23, 2017). 'Cannes: Sony Pictures Classics Buys Cowboy Drama 'The Rider' (EXCLUSIVE)'. Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

^'The Rider (2018)'. Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

^'The Rider Reviews'. Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

^Cheshire, Godfrey (April 13, 2018). 'The Rider'. RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

^Sharf, Zack (December 28, 2018). 'Barack Obama's Favorite Movies of 2018 List Is Here, and It's Pretty Damn Amazing'. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

^'Best of 2018: Film Critic Top Ten Lists'. Metacritic. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

^D'Alessandro, Anthony (November 21, 2017). 'Spirit Award Nominations: 'Call Me By Your Name', 'Lady Bird', 'Get Out', 'The Rider', 'Florida Project' Best Pics'. Deadline Hollywood. Penske Business Media. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

^Wagmeister, Elizabeth (November 26, 2018). 'Gotham Awards: A24 Sweeps With Five Wins, Including 'First Reformed,' 'Eighth Grade' (Full Winners List)'. Variety. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

^Mandinach, Zach (October 18, 2018). 'Nominations Announced for the 28th Annual IFP Gotham Awards'. Independent Filmmaker Project. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

^Brown, Mark (October 31, 2018). 'The Favourite dominates British independent film award nominations'. The Guardian. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

^Lewis, Hilary (November 27, 2018). ''Green Book' Named Best Film by National Board of Review'. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

^Ramos, Dino-Ray (January 5, 2019). 'National Society Of Film Critics Names Chloe Zhao's 'The Rider' As Best Picture'. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

External links[edit]

Official website

The Rider at IMDb

The Rider at AllMovie

The Rider at Box Office Mojo

Rider The App

Retrieved from 'https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Rider_(film)&oldid=1015566981'

0 notes

Link

The bottom line: Kong rules again.

Mix King Kong with The Lost World, spike it with a bracing dash of Apocalypse Now and you've got Kong: Skull Island, in which Warner Bros. finally gets the effects-driven fantasy adventure formula right again after numerous misfires. This highly entertaining return of one of the cinema's most enduring giant beasts moves like crazy — the film feels more like 90 minutes than two hours — and achieves an ideal balance between wild action, throwaway humor, genre refreshment and, perhaps most impressively, a nonchalant awareness of its own modest importance in the bigger scheme of things; unlike most modern franchise blockbusters, it doesn't try to pummel you into submission.

Leagues better than Peter Jackson's bloated, three-hour Kong of 2005, this one looks poised for strong returns and potential sequels co-starring hinted-at monsters from movie lore.

It may have seemed like a stretch to entrust this giant project to a director whose career hitherto consisted of one small, kid-centric Sundance film, the 2013 The Kings of Summer. But it was Jordan Vogt-Roberts who had the crucial inspiration to set this Kong redo in 1973, specifically at the moment the United States pulled out of Vietnam, a decision that nourishes nearly every aspect of the film. Certainly the specter of Col. Kurtz looms over the perilous journey undertaken by this tale's small band of mostly military explorers into unknown tropical territory, but what awaits them is a whole lot bigger and scarier than Marlon Brando.

Smartly operating under the theory that exposition in this sort of thing should quickly be dispatched in order to get to the good stuff, the director, screenwriters Dan Gilroy, Max Borenstein and Derek Connolly and story creator John Gatins have made Skull Island and its environs into a storm-enshrouded location in the Pacific Ocean that has never been charted or found. As the war ends, old-time secret op Bill Randa (John Goodman) convinces the Nixon Administration to back a small expedition to try to find and map the place “where God didn't finish the creation, a place where myth and science meet,” as Randa alluringly puts it. Goodman gets several of the writers' best lines, including one designed to reference Vietnam but that will register with modern viewers: “Mark my word, there'll never be a more screwed up time in Washington.”

A crew is ferried by about a dozen choppers that penetrate the dense fog and rain to find what Skull Island has to offer. Among the key members are Samuel Jackson's bitter Lt. Colonel Packard, who's pissed that the U.S. didn't finish the job in Nam and brings with him his team of “Sky Devils” with quick trigger fingers; Tim Hiddleston's Capt. Conrad, a sleek SAS black ops vet now at loose ends; Brie Larson as combat photographer Mason Weaver; and Corey Hawkins as a bookish biologist, all of whom have their own agendas to pursue in a land unknown to man.

Unknown, that is, except to one man, Hank Marlow (John C. Reilly), a pilot who crashed there during World War II and has lived peaceably among a few silent natives ever since. Looking like an old hippie with his tattered uniform and untended beard, Marlow has somehow survived through the years with his humor and good will intact, and Reilly's warmly funny performance becomes the heart of the film; he could have been just comic relief in an old coot Walter Brennan-style turn but, in stressing the character's generous acceptance of his strange fate, the actor makes the man embraceably multidimensional and accessible (one of the Chicagoan's first questions of his visitors, along with who won World War II, is whether the Cubs have won anything yet).

In the end, though, it's not the characters the audiences will have come to see, but the monsters, and the film doesn't stint in supplying them. This Kong, who makes his entrance a well-timed half hour in, is far bigger than any before him, about 100 feet tall. Still, he faces fierce competition on the island from, among others, some toothsome lizards who happily take advantage of the change in diet offered by the new human visitors.

As before, Kong himself is portrayed as fearsome but also observant and sensitive. The tragic element to his character is carried over from previous incarnations; he's the last of his species, and the bones of his family are strewn about the ground. Unfortunately, he's got a new enemy in Packard, who is determined to settle his unfinished business in Nam by taking out Kong, as if that would somehow right the balance.

Its numbers steadily decreasing as it goes, the expedition struggles against rugged terrain and a nasty environment to make it to the far side of the island, where they're due to be picked up in three days. Mason snaps away at all the freakish wonders to provide photographic evidence, while Capt. Conrad, the nominal handsome male lead, really doesn't engage in many heroics, perhaps the better to allow Hiddleston's neatly styled hair to remain perfectly in place throughout. And despite his helping Mason out of a jam or two, the expected romantic sparks remain unlit, which may be a sign not only of the times, but of the director's relentless determination to avoid cliches and eliminate the “boring parts,” as kids used to call the inevitably bland love scenes in such films.

Instead, there is considerable emotional investment to be made in Reilly's character, who is no doubt not named Marlow for nothing. Despite his decades of deprivation, he's the best-adjusted character on hand, his relaxed acceptance of his odd destiny becoming palpably moving at times, a reaction never sought or expected in this sort of film. At least as far as the humans are concerned, Reilly steals the film.

That said, Vogt-Roberts and his collaborators make sure to take care of business where it really counts, which is in the invention and excitement of the monster scenes. Fully realistic creatures are now nothing new, but the filmmakers, notably led by visual effects supervisors Stephen Rosenbaum and Jeff White, have engineered scenes of bestial combat that are not only hyper-credible but shot through with unexpected, and often gruesomely funny, moves. The digital zoo is colorful indeed, from a towering spider to a giant water buffalo and an all-embracing octopus, making it clear that Kong has his hands full of worthy opponents on a regular basis. It's no wonder the old guy seems world-weary.

All the requisite elements are served up here in ideal proportion, and the time just flies by, which can rarely be said for films of this nature, which, in a trend arguably started by Peter Jackson, have for years now tended to be heavy, lumbering and overlong. A post-end credits bit suggests that Warner Bros. already has some famous opponents lined up for Kong's heavyweight belt, beginning perhaps with Rodan. Whoever undertakes any follow-ups will have a high bar to clear.

Production company: Legendary Pictures Distributor: Warner Bros. Cast: Tom Hiddleston, Samuel L. Jackson, John Goodman, Brie Larson, John C. Reilly, Jing Tian, Toby Kebbell, John Ortiz, Corey Hawkins, Jason Mitchell, Shea Whigham, Thomas Mann, Terry Notary Director: Jordan Vogt-Roberts Screenwriters: Dan Gilroy, Max Borenstein, Derek Connolly, story by John Gatins Producers: Jon Jashni, Alex Garcia, Thomas Tull, Mary Parent Executive producers: Eric McLeod, Edward Cheng Director of photography: Larry Fong Production designer: Stefan Dechant Costume designer: Mary E. Vogt Editor: Richard Pearson Music: Henry Jackman Senior visual effects supervisor: Stephen Rosenbaum Visual effects supervisor: Jeff White Casting: Sarah Haley Finn

Rated PG-13, 119 minutes

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://www.classicfilmfreak.com/2017/08/10/big-sleep-1946-starring-humphrey-bogart-lauren-bacall/

The Big Sleep (1946) starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall

“Let me do the talking, angel. I don’t know yet what I’m going to tell them. It’ll be pretty close to the truth.”-Philip Marlowe

Seven bodies! At least that’s the rumored total in Raymond Chandler’s novel The Big Sleep. When William Faulkner and Leigh Brackett were working on the film’s screenplay and couldn’t discern who had murdered one character, they called the author. Chandler told them his identity was in the book, to read it. After checking his own novel, Chandler called back sometime later and told the writers that he didn’t know, that they could designate the killer as they liked.

The two screenwriters, even with the talents of a third, Jules Furthman, remained confused by the already confusing first novel of Chandler, and generally retained that murkiness, which might be one of the film’s charms. The Big Sleep is the best of the few detective films Warner Bros. made after The Maltese Falcon during the 1940s. If not plot, then, the big pluses include the tight direction of Howard Hawks, the sharp-edged dialogue—there’s a lot of talking—and the romantic repartee between its two stars, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

Despite Bacall’s come-hither, deep-voiced overtures to her leading man, anyone who has seen the first scene will be astounded by the schoolgirl teasings, no less provocative, of Martha Vickers as a precocious nymph, Bacall’s sister in the film, and wonder why she’s not seen more.

In fact, Vickers’ sexy chemistry was so threatening to the studio’s new discovery—this only Bacall’s fourth film after her sensational début in To Have and Have Not (1944)—that most of the younger (by about eight months) star’s scenes were cut. A major overhaul of Bacall’s part by the studio and director ensued, with reshoots, new scenes and added sexual innuendos between her and Bogart.

Filming was further complicated by the tension of Bogart’s impending divorce from his third wife and the affair he was conducting on the set with Bacall. Rumor had it that Bacall was so nervous over the divorce, and, from some sources, that the actor was still debating whether to proceed with the divorce, that during filming her hands shook when she poured a drink or lighted a cigarette.

Bacall had written in her autobiography, By Myself, that, despite the anxiety over the divorce, much fun was had on the set, which prompted a cautionary memo from studio head Jack L. Warner. And when the most famous of the screenwriters, William Faulkner, author of The Sound and the Fury and other stories of the South, asked Hawks if he could write “from home,” since the studio atmosphere unnerved him, Hawks okayed the request, assuming the writer meant his office at the studio. The director was quite displeased when he learned that Faulkner was writing from“home” all right—in Oxford, Mississippi.

Some brave souls have tried to condense the impenetrable plot into a nutshell, though, at best, it’s of minimum importance. Let’s see, how does it go, or appears to go. . . .

Private detective Philip Marlowe (Bogart) visits a decaying old man, General Sternwood (Charles Waldron, who died before the film was released), who sits, wheelchair-bound, shawl-enshrouded, in his putrefying greenhouse. (In the 1978 remake, James Stewart’s portrayal of the role seems more a copy of Waldron’s performance than any original approach of his own.) The dialogue in this one scene, and coming so early in the film, can be seen as setting the ethical tone of the movie and the nature of the characters, the private eye included.

The General says to Marlowe:

“You may smoke, too. I can still enjoy the smell of it. Hum, nice state of affairs when a man has to indulge his vices by proxy. You’re looking, sir, at a very dull survival of a very gaudy life—crippled, paralyzed in both legs, barely I eat and my sleep is so near waking it’s hardly worth the name. I seem to exist largely on heat, like a newborn spider.”

He tells Marlowe that he’s being blackmailed, again, and asks him to check on the gambling debts his younger daughter, Carmen (Vickers), owes to a book dealer named Geiger (Theodore von Eltz). (Carmen is a nymphomaniac in Chandler’s novel, but the Hollywood censors would permit no more than what is seen; any inferences otherwise must be the viewer’s own.)

As Marlowe is leaving, the butler (Charles D. Brown) tells him Mrs. Vivian Rutledge (Bacall) would like to see him. In trying to feel him out, she confides that she believes her father has asked him to search for his friend Sean Regan, who has been missing for a month.

Next scene, Marlowe visits Geiger’s rare bookstore (a source for pornography in Chandler’s novel). With the front of his hat turned up, he assumes a clipped speech and eccentric manner, asking for specific editions of two books. The proprietor (Sonia Darrin) says she doesn’t have them.

He then goes across the street to another book store run by a proprietress (Dorothy Malone) who comes on to Marlowe, and he to her. He asks her for the same editions of the books and she rightly tells him there are none. “The girl in Geiger’s bookstore,” he says, “didn’t know that.”

He asks her if she knows Geiger on sight, she describes him down to his glass eye and he requests she let him know when he comes out of the bookstore. (The three-and-a-half-minute scene is one of the best in the film, and, interesting, like Marlowe’s scene with Sternwood, it exudes rapport and chemistry without Bacall.)

When Geiger does emerge, Marlowe follows him to a house. Hearing a woman’s scream and a gunshot, he enters to find a dead Geiger, a drugged Carmen and a hidden camera, without any film. After taking Carmen home, he returns to the house, only to find . . . the body is gone.

It’s just the beginning, and from here on it’s nothing but a convoluted, indecipherable mess, first and most prominent, murder, then gambling, blackmail, car chases (not the apoplectic ones of today), love triangles, red herrings, organized crime, subtle suggestions of pornography and general mayhem.

Although no threat to the overwhelming charisma between Bogart and Bacall, the dialogue has its own fascination, often poetic and occasionally unforgettable, however “written” it may sometimes sound. This is true of General Sternwood’s lines in his one scene and in some of Marlowe’s, particularly this retort during his first scene with Vivian, when she says she deplores his manners:

“And I’m not crazy about yours. I didn’t ask to see you. I don’t mind if you don’t like my manners. I don’t like them myself. They are pretty bad. I grieve over them on long, winter evenings. I don’t mind you ritzing me or drinking your lunch out of a bottle, but don’t waste your time trying to cross-examine me.”

These lines, some given at a fast, breathless pace, are reminiscent of a Bogart scene in The Maltese Falcon—the address to the district attorney about “the only chance I’ve got of catching them [the murderers], and tying them up, and bringing them in, is by staying as far away as possible from you and the police . . . ”

The most famous dialogue exchange, with its sexual innuendos, is between Bogart and Bacall, sitting across from each other at a nightclub table:

“Speaking of horses,” she says, “I like to play them myself. But I like to see them work out a little first, see if they’re front runners or come from behind, find out what their hole card is, what makes them run. . . . I’d say you don’t like to be rated. You like to get out in front, open up a little lead, take a little breather in the backstretch and then come home free.”

“You don’t like to be rated yourself,” he says.

“I haven’t met any one yet who can do it. Any suggestions?”

“Well, I can’t tell till I’ve seen you over a distance of ground. You’ve got a touch of class, but I don’t know how far you can go.”

“A lot depends on who’s in the saddle.”

This scene doesn’t need, and doesn’t receive, any underpinning music. Max Steiner’s musical score is one of his more problematic, containing both the strong and weak points of his style. The main title is something of a nondescript blur, noisy and tuneless, serving, if nothing else, as a foretaste of the impervious plot and unsavory characters.

In the insouciant motif for Philip Marlowe, Steiner captures the detective’s sluggish, yet quixotic nature, which serves to brighten the predominantly dark music. The slowly ascending notes at the start of the main love theme suggest, perhaps—assuming Steiner’s thinking was this nuanced—the hostile beginning of Marlowe and Vivian’s relationship, the rest of the theme infused with a kind of smothered passion their love would become by the end.

In scoring for two similar settings, it is interesting to compare the disparate approaches to the greenhouse scene, with all its tropical trees and ferns, and Violet Venable’s (Katharine Hepburn) jungle garden in Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). For whatever the reason, Steiner elects to ignore representing the humid atmosphere General Sternwood has prepared for his orchids, while composers Malcolm Arnold and Buxton Orr convey almost breathable damp and mildew for Violet’s steamy surroundings.

The Big Sleep is a film where everyone except General Sternwood—perhaps he, too, if he had another scene—carries a gun, and when guns are unavailable, then fists do quite well. With the moral slant of the film, that is, with less than admirable characters and their ugly motives, it’s hard to like any of them.

Truth is, you’re not supposed to like the characters in a film noir, sympathize with them maybe.. But the actors you can like. It’s hard not to like Bogart and Bacall—not as accomplished actors, but as personalities of the screen, as stars were viewed in the ’30s and ’40. Then movie-goers didn’t go to see Philip Marlowe or Vivian Rutledge, not that any one coming out of the theater would remember her last name; they went to see Bogart and Bacall.

Bogart, like Cagney and Flynn, is a personality, a man who always, or generally always, plays himself. Bacall, who still hadn’t learned to act at the time of The Big Sleep, would have been easily overshadowed by Vickers had her original scenes been left intact, and Dorothy Malone has all the charisma and magic of Bacall, just another kind of charm.

Bosley Crowther, one of the most famous movie critics of the 1940s, warned in his New York Times review of August 24, 1946, that the film would be confusing and unsatisfying. And apparently in all sincerity, he asked, “[W]ould somebody also tell us the meaning of that title . . . ” Why, it’s what seems obvious, that which at least seven of the characters in The Big Sleep experienced . . . DEATH.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n-K49CUaeto

0 notes

Link

America’s No.1 Detective Agency

There has always been a crossover between the movies and theatre. Hollywood and Broadway have proved time and again that they can co-exist and learn from each other. Take ‘Hairspray’. This started off as a film, then was redone for musical theatre and then redone again for a movie. So celluloid and grease-paint can co-exist peacefully. There is an example of this at the Drayton Arms Theatre where Fatale Femmes presents America’s No 1 Detective Agency.

In downtown LA, private investigator Vivian O’Connell (Fleur de Wit) is worried about her business. Along with sidekick Joey Vincent (Siobhan Cha Cha), Vivian is waiting for a big case to walk through the door so that she re-establish herself and take over from Bobby Munroe (Hamish Adams-Cairns) as the No 1 PI in America. Unfortunately, the only case that comes their way is brought in by wannabe Hollywood starlet Betty Channing (Alex Hinson). Betty has a problem with obscene photographs and, although she knows it is really beneath her, Vivian agrees to take the case. Vivian heads to the seediest bar in town to investigate the pictures with the help of her friend/snitch Edward “Teddy” Worthington (Iain Gibbons) and mob boss Larry Siegeli (Oliver-David Harrison). As the investigation proceeds, Vivian finds out that things are not as plain as they appear and who someone is not necessarily who they are.

Presented in a sort of film noir pastiche, America’s No 1 Detective Agency is an unusual piece of theatre. Writer Liv Hunterson has managed to cram an awful lot into a seventy-five-minute show. In fact, at times, I felt there was so much going on I was in danger of missing parts of the – even for film noir – rather convoluted story. Having said that, there were certainly elements of the script which tickled my funny bone – for example the stuck door, and the initial belligerence of Joey to Betty when she first arrived in the office.

Natalie Jackson’s set was very film noir with pieces of furniture being moved or wheeled around to create new locales – though I do wish someone had got an oil can to the castors of the desk. James Stokes lighting worked nicely with the story and I really liked the idea of having live background music (Danny Wallington and Justin Tambini) with the gorgeous singing voice of Isabella Bassett.

With all these elements, Director Anna Marshall has a lot to do to ensure everything runs smoothly and, this she accomplishes pretty well. My one point would be that as everyone is on stage virtually the whole time there needs to be some thought about what the actors are doing when not taking part in the main action, once or twice there were movements at the back of the stage which caught my attention and distracted me.

Turning to the actors, and they were all good in their roles, but full credit to the ladies for their performances. In most shows like this, the lead would be a man so it was nice to see PI Vivian O’Connell as the main character. Fleur De Wit played the part well, maintaining her femininity whilst still using the clipped voice so beloved of guys like Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe – a very nice crossover there.

Overall then, America’s No 1 Detective Agency is a difficult show for me to sum up. I’m not particularly a fan of film noir as a movie style and also maybe this just isn’t my sort of play. As stated above, I did feel that there was at times too much going on and, unusually for me, I would recommend adding another few minutes to the run-time just to give everyone a chance to catch-up. And while the story may have been convoluted, the production itself was pretty good. Not necessarily my cup of tea but if you like the style, it should be right up your alley.

Review by Terry Eastham

A Noir Comedy inspired by classics such as Mildred Pierce and The Third Man. Fatale Femme present their debut play written by Liv Hunterson and directed by Anna Marshall at the Drayton Arms.

America’s No.1 Detective Agency uses fast paced physical theatre inspired by noir films and the comedies of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin to tell the story of Vivian O’Connell; who was the best detective in Los Angeles. That was until the Wallace case exploded and Bobby Munroe took her title, and all the good cases with it.

In a town where everyone has a part to play, just how far will Vivian have to go to reconcile her title and prove herself as the number one detective in America. When a distressed starlet comes asking for help, Vivian has no choice but to take a case that’s beneath her (in more ways than one) in this hilarious noir romp.

Cast Fleur de Wit appearing as Vivian O’Connell Siobhan Cha Cha appearing as Joey Vincent Alex Hinson appearing as Betty Channing Hamish Adams-Cairns appearing as Bobby Munroe Iain Gibbons appearing as Edward “Teddy” Worthington Oliver-David Harrison appearing as Larry Siegeli

Creatives: Director: Anna Marshall, Assistant Director: Isabella Bassett, Writer: Liv Hunterson, Designer: Natalie Jackson, Lighting Designer: Katrin Padel, Press: Heather Ralph, Produced by Fatale Femme

Venue details: Drayton Arms Pub & Theatre, 153 Old Brompton Road, London, SW5 0LJ Dates and Times: 8pm, 30th July – 7th Aug.

http://ift.tt/2v2NTHP LondonTheatre1.com

0 notes