#a. s. hamrah

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"The system of making reality TV reflected its content in that regard. Making a show became a beat-the-clock endeavor in which there wasn’t enough time or money to get things right. Instead, suffering and tension were added to what should have been mundane work duties, the same way those elements were added into dating or cooking shows to ratchet up the conflict in areas that are supposed to be pleasurable, loving, or fun, not terrifying, hurtful, and vindictive." - A. S. Hamrah, Time To Face Reality

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

August 2023 reading

Books:

Langston Hughes, Selected Poems

T. H. White, The Sword In The Stone

T. H. White, The Witch In The Woods

T. H. White, The Ill-Made Knight

T. H. White, The Candle In The Wind

Articles:

Lisa Borst, Ari M. Brostoff, Cecilia Corrigan, Jon Dieringer, A. S. Hamrah, Arielle Isack, Mark Krotov, Jasmine Sanders, Christine Smallwood, Who Was Barbie?

Lev Grossman, The gay Nabokov

Yasha Levine, Immigrants as a Weapon: Global Nationalism and American Power

Sophie Lewis, Cthulhu plays no role for me

Gail Omvedt, The doubly marginalised

John Semley, Oppenheimer and the Dharma of Death

Bassam Sidiki, Severances: Memory as Disability in Late Capitalism

towardrecomp, Fidelidad En La Tormenta: Part 1

Eyal Weizman, The Art of War: Deleuze, Guattari, Debord and the Israeli Defense Force

Short stories:

Tamsyn Muir, Chew

Tamsyn Muir, The Unwanted Guest

Rebecca Fraimow, Further Arguments In Support Of Yudah Cohen's Proposal To Bluma Zilberman

Rebecca Fraimow, Gitl Schneiderman Learns To Live With Her In-Laws

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

—A. S. Hamrah

Anyway this got me to watch The Doll and that SURE WAS a gender bind!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

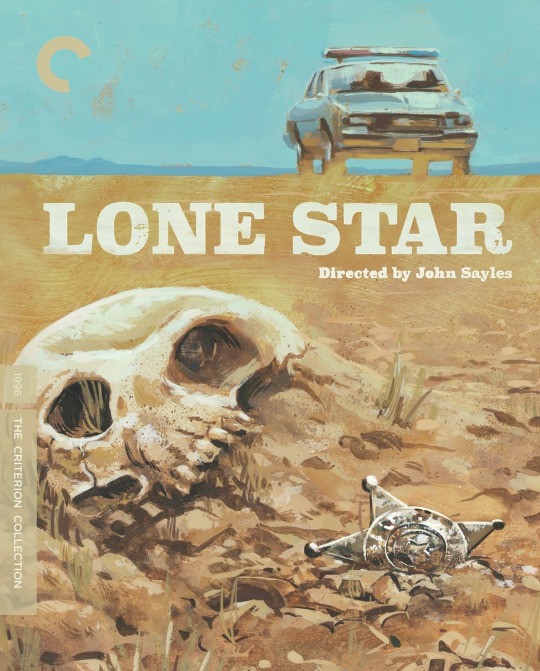

On January 16th, the @criterioncollection will release Lone Star on both 4K uhd blu-ray and regular blu-ray with following extras:

DIRECTOR-APPROVED SPECIAL EDITION FEATURES

New 4K digital restoration, supervised by director John Sayles, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray

Audio commentary from 2013 featuring Sayles and cinematographer Haskell Wexler

Two new documentaries on the making of the film featuring Sayles, producer Maggie Renzi, production designer Nora Chavooshian, and actors Chris Cooper, James Earl Jones, Mary McDonnell, Will Oldham, and David Strathairn

New interview with composer Mason Daring

Short documentary on the impact that Matewan’s production had on West Virginia

New program on the film’s production design featuring Chavooshian

Trailer

English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

PLUS: An essay by critic A. S. Hamrah

New cover by Eric Skillman

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WHITNEY REVIEW Of New Writing Issue 002 Winter 2023/2024

THE SECOND ISSUE OF THE WHITNEY REVIEW OF NEW WRITING

Issue 002 Winter 2023 / 2024

THIS ISSUE IS ABOUT DESPERATION, EXCESS, ROMANCE, AND GRIEF

A collection of original author interviews, book reviews, and essays from the sharpest cultural commentators including:

MCKENZIE WARK X JOURNEY STREAMS MICHELLE TEA X CASEY JANE ELLISON TRAVIS JEPPESEN X SLAVA MOGUTIN ESSAYS BY EM BRILL, DAVID FISHKIND, AND STEVEN PHILLIPS HORST

POETRY BY CRISTINE BRACHE AMALIA ULMAN ON NATASHA STAGG REVIEWS BY A. S. HAMRAH, DIAMOND STINGILY, DREW ZEIBA, JOHANNA FATEMAN, MAYA MARTINEZ, GEOFFREY MAK, RACHEL OYSTER KIM, LILY MAROTTA, PAUL KOPKAU, JUSTIN MORAN, JOHN BELKNAP, PHILIPPA SNOW, COLLEEN KELSEY, TAMARA FAITH BERGER, KAWAI SHEN, VIVIEN LEE, NATE LIPPENS, HALEY MLOTEK, ALISSA BENNET, ESRA SORAYA PADGETT, T. AMOLO OCHIENG' NYONG'O, MAX STEELE, TONY JACKSON, NABEN RUTHNUM, AND MORE...

READ ABOUT IT IN OFFICE MAGAZINE

1 note

·

View note

Text

At the end of August 2020, Tom Cruise was on a mission to prove it was safe to go back to the movies. Donning a black mask over his nose and mouth, the actor sped off to see Christopher Nolan’s Tenet as it opened in London. Such was the confusion of that summer in the film industry that even as Tenet debuted, Access Hollywood, the entertainment news TV show, pronounced the title of Nolan’s film “ten-AY,” to rhyme with bidet. “Back to the movies,” Cruise said as he entered the theater by himself, very low-key. A hundred and fifty minutes later, exiting up the stairs, he quietly answered “I loved it” to someone in the audience who asked what he thought. A perfectly timed stealth mission: Cruise swooped in and out. Theatrical film exhibition would not die on his watch.

But as watchers of his Mission: Impossible movies know, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Four months later, on the set of Mission: Impossible–Dead Reckoning, Part One, then called simply Mission: Impossible 7, Cruise was caught on tape berating his crew for violating Covid protocols. “We are not shutting this fucking movie down!” he yelled. “If I see you do it again, you’re fucking gone…. No apologies. You can tell it to the people that are losing their fucking homes because our industry is shut down.” The recording was leaked to a British tabloid; quickly social media pointed out that the old Tom Cruise, the one notorious for manic rants during which he did things like mansplain Brooke Shields’s postpartum depression on The Today Show, was back.

Production on the new Mission: Impossible movie had been halted three times before Cruise’s outburst, while the release of his Top Gun sequel, Top Gun: Maverick, completed in 2019, had been postponed again and again. He was on edge, but as it turned out there was nothing to worry about. In a career that has been defined by the greatest luck and hardest work, these delays worked to his advantage. Finally released last summer, Maverick was an enormous hit. It has made $1.5 billion to date, and is credited—largely credited, as they say—with saving Hollywood from ruin.

Mission: Impossible–Dead Reckoning, Part One, also delayed about two years, came out this summer and nearly performed the same feat as Top Gun: Maverick did. It raked it in at the box office after a full year of non–Tom Cruise movies like The Flash tanked—bad movies that are part of bad cycles that have gotten worse, and which no longer make money. The new M:I movie emerges into what is arguably a more perilous time for Hollywood than the pandemic, with studios threatening to use artificial intelligence to replace writers and actors, whose unions have called strikes. This potential new digital blight is coupled with the cheapness of the studio bosses in the streaming era, who goosed their studios’ stock value during the pandemic and prefer to cut costs rather than share the wealth.

And yet nobody is going to thank Tom Cruise twice, not this year. As we wait until next summer or later for Part Two of Cruise’s multimillion dollar cliffhanger, production of which has been shut down by the Screen Actors Guild strike, mania for the binary of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Nolan’s Oppenheimer has gripped a world suddenly rich with quality non-superhero blockbuster success stories. Add to that the very unexpected smash breakout of another long-delayed movie, the right-wing action thriller Sound of Freedom, and suddenly the movies are back. They are so back it’s almost like they have returned to a time before the superhero apocalypse—that computer-generated miasma instrumental in training AI to take over—ground them into digital dust. In that era, Cruise was the last man standing. Now all of a sudden he is underperforming, despite his movie taking in more than $400 million worldwide so far.

*

Recently I saw the 1980 espionage thriller-comedy Hopscotch, starring Walter Matthau as a CIA agent fired for sticking to his old ways in an increasingly corporatized spy biz. Matthau was sixty when he made it, the same age as Tom Cruise when he was making Dead Reckoning. It goes without saying that these two quintessential American actor/movie stars have little in common. Cruise’s Ethan Hunt is all action, his emotions hidden, his skills surprising, his loyalty to his team and their mission limitless. He is the master of every machine and gadget. We are meant to understand that he can do anything. Matthau, by contrast, chooses to do almost nothing. He shows no loyalty, wears his disgruntlement on his sleeve, and chews scenery. Always old before his time, Matthau lingers in cafés going over notes, scheming to make his bosses look dumb.

Hopscotch includes the things Mission: Impossible movies leave out. We see Matthau haggling over safe house rentals and forged passport prices, buying clothes for his disguises, walking around empty fields as he silently plans. As for gadgets, he uses a paperclip to short out the lights in a police station, the paperclip being the one device Hopscotch shares with Dead Reckoning. There, Hayley Atwell, playing a thief, uses one to free herself from handcuffs, then uses them to attach Cruise to the steering wheel of a Fiat 500, which is trapped in a tunnel where it is of course about to be hit by an oncoming train.

Cruise at sixty still does his own stunts, which appear more dangerous and extreme with each of these movies, especially since he has teamed with the director-screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie, starting with the fifth in the series, Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation (2015). Legitimately thrilling, their set pieces are nonstop inventive in the manner of can-you-top-this American know-how, returned to ultra-professional glory from the dirtbag daring of the Jackass movies, their natural competition (rather than The Flash). Matthau at sixty, on the other hand, knew one real test of cinematic greatness was the ability to sit there and do nothing and still hold the screen. We cannot picture Matthau at that age or at any age learning to hold his breath for nine minutes so he could do an underwater stunt in tactical gear holding a flashlight in his mouth.

It is hard to believe that when the first Mission: Impossible movie debuted in 1996, Cruise had already been a movie star for thirteen years. When Brian De Palma’s film version of the TV series came out with Cruise and Jon Voight, the actors from the original 1960s show complained. The movie was nihilistic, there were double agents in it, it wasn’t patriotic. These were strange objections from the stars of a series that featured extrajudicial assassinations, unofficial regime change, and state-sanctioned kidnappings.

In fact, the movie, post–cold war, kept the best parts of the show: the lifelike masks characters use to impersonate each other, allowing actors to play two parts with the same face, and the idea that espionage was a series of short or long cons more like theater acting and stage magic than diplomacy by other means.

De Palma also linked the franchise to cinema history in a way Cruise and McQuarrie have maintained, bringing the mise-en-scene and the mood all the way back through Hitchcock to German Expressionism via the silent crime and spy movies Fritz Lang made in the 1920s, Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler and Spione. Right away, in the first scene of De Palma’s film, a tense interrogation is deconstructed before our eyes as the walls of the set are moved aside or flattened to reveal an empty warehouse—the soundstage itself—while the actors peel off their faces, revealing nothing beneath them but the faces of other actors.

As in Hopscotch, but not in the TV series, the enemy in the Mission: Impossible movies is within. It is always a competing government spy agency that is stopping Cruise and his team from accomplishing the mission they have chosen to accept. Beneath the deep state is a deeper state still. Fittingly, as on the TV show, the news of these missions comes from a tape recorder that self-destructs, as if Cruise has found a stray Nagra on the set that instead of being used to record dialogue has been rigged to emit some smoke before the editor cuts away from it and the theme music starts to play. That music, by Lalo Schifrin, is the prime intellectual property in this series of films, in itself a reason to keep making them, and in its dot-dash intensity a spur to make them good.

*

Cruise’s employers are always disavowing him in these movies. He returns to work like Charlie Brown coming back to kick the nuclear football while Lucy holds it for him again. Dead Reckoning, despite its setbacks, has the lucky perspicacity to appear to be seeing into the future. The overarching conspiracy here has to do with a killer AI set to take over the world’s entire OS, forever blurring the line between reality and illusion, truth and lie. More than ever, the M:I films are about the nature of the film industry itself, and the way stories are told by actors—actors who seem to act as writers, writing the movie as they go along.

The AI, therefore, can take over spy systems and imitate a familiar voice (Simon Pegg’s), then say into Cruise’s earpiece, “Go left! No, go right! No, go left!” as he chases an assassin, in imitation of the directions in a screenplay or those given by a director on set. Of course the AI paints him into a corner—it exists to ruin his performance. In Dead Reckoning, both Cruise and the entire US surveillance apparatus have to go fully analog to fight their AI enemy, a narrative turn that both reaffirms the movie’s dedication to filming real stunts in front of the camera and presciently combats the studio bosses’ insistence on a new filmmaking world of computer-generated screenplays and performances along with special effects.

One of the most admirable lines in the movie comes after Atwell’s character asks Cruise and his team why they are willing to help her, since they don’t even know her. “What difference does that make?” he asks, a fading echo of Hawksian professionalism and humanism in this globalized landscape, part of this film series’ (and Cruise’s) anti-psychological approach, where backstory always struggles to be buried and forgotten, and usually is. It’s the opposite of the maudlin nonsense about family in the Fast & Furious movies.

It is hard to ignore that Cruise has looked a little tired during the extensive, international press tour for Dead Reckoning. Visibly older than when he went to see Tenet in London three years ago, he nonetheless exudes a kind of perplexed, patient bonhomie as he travels the world to sell his film, his slightly disconnected, mechanized mien and tense bearing now newly patient, an aura that envelops the entire category “movie star.” In cinemas, before the film starts, a very short clip of Cruise and McQuarrie plays in which the star-producer and writer-director thank the audience for seeing their movie in a theater, where they made it to be seen. McQuarrie, gray-haired and gray-bearded, gets to look his age; Cruise is locked in, in more ways than one.

With the temporary shutdown of Dead Reckoning, Part Two, Cruise is once again stuck in the quagmire of twenty-first-century studio filmmaking, where every crisis resolves in stasis. Will there come a time for him when that kind of entropy beats his luck and hard work? So much went wrong in making Part One. When the young British actor Nicholas Hoult, slated to play the film’s principal villain, dropped out, Cruise and McQuarrie or someone got the idea to replace him with the journeyman trouper Esai Morales. What luck that the most calm, cool, and collected character in the movie, and the best-looking and most evil, just happens to be a man for today—a pro-union Puerto Rican TV actor from Brooklyn the exact same age as Cruise. On such accidental genius the Hollywood cinema survives another year.

1 note

·

View note

Text

At the end of August 2020, Tom Cruise was on a mission to prove it was safe to go back to the movies. Donning a black mask over his nose and mouth, the actor sped off to see Christopher Nolan’s Tenet as it opened in London. Such was the confusion of that summer in the film industry that even as Tenet debuted, Access Hollywood, the entertainment news TV show, pronounced the title of Nolan’s film “ten-AY,” to rhyme with bidet. “Back to the movies,” Cruise said as he entered the theater by himself, very low-key. A hundred and fifty minutes later, exiting up the stairs, he quietly answered “I loved it” to someone in the audience who asked what he thought. A perfectly timed stealth mission: Cruise swooped in and out. Theatrical film exhibition would not die on his watch.

But as watchers of his Mission: Impossible movies know, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Four months later, on the set of Mission: Impossible–Dead Reckoning, Part One, then called simply Mission: Impossible 7, Cruise was caught on tape berating his crew for violating Covid protocols. “We are not shutting this fucking movie down!” he yelled. “If I see you do it again, you’re fucking gone…. No apologies. You can tell it to the people that are losing their fucking homes because our industry is shut down.” The recording was leaked to a British tabloid; quickly social media pointed out that the old Tom Cruise, the one notorious for manic rants during which he did things like mansplain Brooke Shields’s postpartum depression on The Today Show, was back.

Production on the new Mission: Impossible movie had been halted three times before Cruise’s outburst, while the release of his Top Gun sequel, Top Gun: Maverick, completed in 2019, had been postponed again and again. He was on edge, but as it turned out there was nothing to worry about. In a career that has been defined by the greatest luck and hardest work, these delays worked to his advantage. Finally released last summer, Maverick was an enormous hit. It has made $1.5 billion to date, and is credited—largely credited, as they say—with saving Hollywood from ruin.

Mission: Impossible–Dead Reckoning, Part One, also delayed about two years, came out this summer and nearly performed the same feat as Top Gun: Maverick did. It raked it in at the box office after a full year of non–Tom Cruise movies like The Flash tanked—bad movies that are part of bad cycles that have gotten worse, and which no longer make money. The new M:I movie emerges into what is arguably a more perilous time for Hollywood than the pandemic, with studios threatening to use artificial intelligence to replace writers and actors, whose unions have called strikes. This potential new digital blight is coupled with the cheapness of the studio bosses in the streaming era, who goosed their studios’ stock value during the pandemic and prefer to cut costs rather than share the wealth.

And yet nobody is going to thank Tom Cruise twice, not this year. As we wait until next summer or later for Part Two of Cruise’s multimillion dollar cliffhanger, production of which has been shut down by the Screen Actors Guild strike, mania for the binary of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Nolan’s Oppenheimer has gripped a world suddenly rich with quality non-superhero blockbuster success stories. Add to that the very unexpected smash breakout of another long-delayed movie, the right-wing action thriller Sound of Freedom, and suddenly the movies are back. They are so back it’s almost like they have returned to a time before the superhero apocalypse—that computer-generated miasma instrumental in training AI to take over—ground them into digital dust. In that era, Cruise was the last man standing. Now all of a sudden he is underperforming, despite his movie taking in more than $400 million worldwide so far.

*

Recently I saw the 1980 espionage thriller-comedy Hopscotch, starring Walter Matthau as a CIA agent fired for sticking to his old ways in an increasingly corporatized spy biz. Matthau was sixty when he made it, the same age as Tom Cruise when he was making Dead Reckoning. It goes without saying that these two quintessential American actor/movie stars have little in common. Cruise’s Ethan Hunt is all action, his emotions hidden, his skills surprising, his loyalty to his team and their mission limitless. He is the master of every machine and gadget. We are meant to understand that he can do anything. Matthau, by contrast, chooses to do almost nothing. He shows no loyalty, wears his disgruntlement on his sleeve, and chews scenery. Always old before his time, Matthau lingers in cafés going over notes, scheming to make his bosses look dumb.

Hopscotch includes the things Mission: Impossible movies leave out. We see Matthau haggling over safe house rentals and forged passport prices, buying clothes for his disguises, walking around empty fields as he silently plans. As for gadgets, he uses a paperclip to short out the lights in a police station, the paperclip being the one device Hopscotch shares with Dead Reckoning. There, Hayley Atwell, playing a thief, uses one to free herself from handcuffs, then uses them to attach Cruise to the steering wheel of a Fiat 500, which is trapped in a tunnel where it is of course about to be hit by an oncoming train.

Cruise at sixty still does his own stunts, which appear more dangerous and extreme with each of these movies, especially since he has teamed with the director-screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie, starting with the fifth in the series, Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation (2015). Legitimately thrilling, their set pieces are nonstop inventive in the manner of can-you-top-this American know-how, returned to ultra-professional glory from the dirtbag daring of the Jackass movies, their natural competition (rather than The Flash). Matthau at sixty, on the other hand, knew one real test of cinematic greatness was the ability to sit there and do nothing and still hold the screen. We cannot picture Matthau at that age or at any age learning to hold his breath for nine minutes so he could do an underwater stunt in tactical gear holding a flashlight in his mouth.

It is hard to believe that when the first Mission: Impossible movie debuted in 1996, Cruise had already been a movie star for thirteen years. When Brian De Palma’s film version of the TV series came out with Cruise and Jon Voight, the actors from the original 1960s show complained. The movie was nihilistic, there were double agents in it, it wasn’t patriotic. These were strange objections from the stars of a series that featured extrajudicial assassinations, unofficial regime change, and state-sanctioned kidnappings.

In fact, the movie, post–cold war, kept the best parts of the show: the lifelike masks characters use to impersonate each other, allowing actors to play two parts with the same face, and the idea that espionage was a series of short or long cons more like theater acting and stage magic than diplomacy by other means.

De Palma also linked the franchise to cinema history in a way Cruise and McQuarrie have maintained, bringing the mise-en-scene and the mood all the way back through Hitchcock to German Expressionism via the silent crime and spy movies Fritz Lang made in the 1920s, Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler and Spione. Right away, in the first scene of De Palma’s film, a tense interrogation is deconstructed before our eyes as the walls of the set are moved aside or flattened to reveal an empty warehouse—the soundstage itself—while the actors peel off their faces, revealing nothing beneath them but the faces of other actors.

As in Hopscotch, but not in the TV series, the enemy in the Mission: Impossible movies is within. It is always a competing government spy agency that is stopping Cruise and his team from accomplishing the mission they have chosen to accept. Beneath the deep state is a deeper state still. Fittingly, as on the TV show, the news of these missions comes from a tape recorder that self-destructs, as if Cruise has found a stray Nagra on the set that instead of being used to record dialogue has been rigged to emit some smoke before the editor cuts away from it and the theme music starts to play. That music, by Lalo Schifrin, is the prime intellectual property in this series of films, in itself a reason to keep making them, and in its dot-dash intensity a spur to make them good.

*

Cruise’s employers are always disavowing him in these movies. He returns to work like Charlie Brown coming back to kick the nuclear football while Lucy holds it for him again. Dead Reckoning, despite its setbacks, has the lucky perspicacity to appear to be seeing into the future. The overarching conspiracy here has to do with a killer AI set to take over the world’s entire OS, forever blurring the line between reality and illusion, truth and lie. More than ever, the M:I films are about the nature of the film industry itself, and the way stories are told by actors—actors who seem to act as writers, writing the movie as they go along.

The AI, therefore, can take over spy systems and imitate a familiar voice (Simon Pegg’s), then say into Cruise’s earpiece, “Go left! No, go right! No, go left!” as he chases an assassin, in imitation of the directions in a screenplay or those given by a director on set. Of course the AI paints him into a corner—it exists to ruin his performance. In Dead Reckoning, both Cruise and the entire US surveillance apparatus have to go fully analog to fight their AI enemy, a narrative turn that both reaffirms the movie’s dedication to filming real stunts in front of the camera and presciently combats the studio bosses’ insistence on a new filmmaking world of computer-generated screenplays and performances along with special effects.

One of the most admirable lines in the movie comes after Atwell’s character asks Cruise and his team why they are willing to help her, since they don’t even know her. “What difference does that make?” he asks, a fading echo of Hawksian professionalism and humanism in this globalized landscape, part of this film series’ (and Cruise’s) anti-psychological approach, where backstory always struggles to be buried and forgotten, and usually is. It’s the opposite of the maudlin nonsense about family in the Fast & Furious movies.

It is hard to ignore that Cruise has looked a little tired during the extensive, international press tour for Dead Reckoning. Visibly older than when he went to see Tenet in London three years ago, he nonetheless exudes a kind of perplexed, patient bonhomie as he travels the world to sell his film, his slightly disconnected, mechanized mien and tense bearing now newly patient, an aura that envelops the entire category “movie star.” In cinemas, before the film starts, a very short clip of Cruise and McQuarrie plays in which the star-producer and writer-director thank the audience for seeing their movie in a theater, where they made it to be seen. McQuarrie, gray-haired and gray-bearded, gets to look his age; Cruise is locked in, in more ways than one.

With the temporary shutdown of Dead Reckoning, Part Two, Cruise is once again stuck in the quagmire of twenty-first-century studio filmmaking, where every crisis resolves in stasis. Will there come a time for him when that kind of entropy beats his luck and hard work? So much went wrong in making Part One. When the young British actor Nicholas Hoult, slated to play the film’s principal villain, dropped out, Cruise and McQuarrie or someone got the idea to replace him with the journeyman trouper Esai Morales. What luck that the most calm, cool, and collected character in the movie, and the best-looking and most evil, just happens to be a man for today—a pro-union Puerto Rican TV actor from Brooklyn the exact same age as Cruise. On such accidental genius the Hollywood cinema survives another year.

0 notes

Text

a starting point, not the sum total

The magazine Harper’s recently published a feature in which a bunch of writers talk about “life after Trump.” They cover various topics: reality, tabloids, movies, relationships, manners, imagination, gold, conversation, punctuation, apologies, golf, literature, and Trump himself. Some of the writers are covering their usual beats: “literature” is covered by the book critic Christian Lorentzen, “movies” by film critic A. S. Hamrah. And some writers cover topics that I know from Twitter they’re already interested in: I’ve seen a number of tweets from Jane Hu, for instance, with quotes on Adorno’s thoughts on punctuation, which also opens her Harper’s piece. Other writers speak to subjects that seem more random, like Liane Carlson’s examination of the decline of the public apology that we saw so often in the early 21st century (with Bill Clinton, Eliot Spitzer, Anthony Weiner, and their like) or Yinka Elujoba on gold: the color, the substance, why it appeals to a certain brand of aristocrat in a certain type of declining empire.

A few of the pieces are inane—showing what can happen when you assemble a piece by giving a bunch of writers a topic to just do whatever they want; different people take mandates differently, and they won’t always be deep—they won’t always be hits. For instance, there’s not much to “Golf” by David Owen. Basically: golf was staid and boring when he first took it up in the early 90s, then it became kind of cool with Tiger Woods’s fame in the late 90s, or at least something people knew about and many people watched, and then all that was undone by Trump’s love of golf the last four years. And that’s well and good, but who cares. Ultimately, Owen’s contribution registers as a marginal blip in the midst of more robust discussions.

But the most inane entry might be Eileen Myles’s contribution to the feature. It’s ostensibly about “relationships.” What it’s actually about is Myles’s feelings. We’ve established before how much I’ve come to distrust writing about how we feel about major developments in politics or about disasters like climate change, rather than the developments and disasters themselves. And at least Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory is a genuine attempt to explore something, even if there are moments when the essays in it drift into ponderousness or sentimentality. In fact, I’ve come to feel less harshly about Gabbert’s book as I’ve thought about the pandemic the last few weeks—how unreal a number like 400,000 deaths feels to me, and how I struggle to know whether this is a natural response. Is a pandemic, with its enormous scale of death, a hyperobject, a phenomenon so vast it can’t really be countenanced by a single human mind? Do large-scale tragedies ever feel real and not abstract to those living through them, when they’re this diffuse? Or is this flatness I feel unique, a sign of some special psychic damage in those of us who are alive today, from social media or the ubiquity of news in the times we live in? I’m more willing to grant that this, how to countenance disaster, is Gabbert’s question; she certainly engages it thoughtfully.

Myles is not thoughtful. It’s striking to read their contribution after you read, say, Hamrah’s brief, potent account of the streaming services’ ascendance in the COVID era, now that we’re all stuck at home and at the mercy of whatever pricing schemes the streaming giants want to set for the movies they release if we want any (legal) entertainment, and how this reflects similar moves last century by studios to force theaters and theater-goers to pay for shit movies as well as better ones. Or Mike Jaccarino’s recent history of tabloids: how Trump depended on them to inflate his image in the 90s and aughts, and how the dynamic reversed over the course of his presidential race and term, with the task of tracking changes in Trump’s image now sustaining them—revealing again the inversion of structures like the media over the course of neoliberalism’s evolution and aftermath. Myles’s piece, so focused on them and how they felt about Joe Biden winning the presidency in 2020, is just so narrow by comparison. Even Charles Yu’s account of the damaging effect the Trump presidency has had on (consensus) “reality” is more interesting. It’s flawed, to my eye, because it so often presents what Trump supporters or QAnoners believe as merely an inferior narrative, a fiction they’ve subscribed to at least somewhat consciously and don’t want disturbed, as though they were all ostriches sticking their heads in the sand rather than people inhabiting the same physical space as Yu himself. And you’re never going to succeed at changing someone’s mind if you’re just convinced they’ve subscribed to a false and inferior narrative—because, as Lauren Oyler notes in her contribution to “Life After Trump,” differences in opinion often come down to different interpretations of the same facts. But even Yu’s contribution is interesting, because it’s not just Yu talking about himself as though his own experience is ours.

Myles’s piece, on the other hand, is just “I, I, I, I, I.” “I was crossing lower Broadway to look at a show,” they write: “I’m a fan…of the work of the artist named Sky Hopinka,” “I had allowed that monster”—Trump—“into my body,” “I went inside the gallery,” “I could hear [the spoken parts of the Hopinka exhibition] pretty well,” “I was in Texas during the earliest parts of COVID and I stayed there for a while and I was keenly aware that this was the first true crisis I had missed in New York”—and on it goes.

And Myles is so irritatingly convinced that their “I” is heroic, or part of a heroic “we,” standing in opposition to Trumpists and to the people in Chelsea, bourgeois and apolitical, who aren’t happy when they see a friend of Myles’s, Joe, pumping up the crowd at the election celebration:

He put his Biden-Harris T-shirt on which was brilliant. Everyone cheers when they see him. He’s like a sign. He starts acting like a sign, saying yay to everyone. Women always say yay, some couples won’t. Or they say a little. Not everyone in Chelsea is happy. They’re doing their Chelsea thing. Shopping, getting some food. This is a disruption. It’s like they didn’t even know there was an election.

I’m not on the side of the Chelsea shoppers here. I’m not on the side of anyone who’s indifferent to their environment, or who sniffs at a public display of any kind of emotion, enforcing some arbitrary idea of seemliness. But how radical is an election, really? How much does this one ultimately change? It’s a minor fluctuation in a long interregnum. I see these lines of Myles’s and I think, If you were really radical, you’d know that. You’d know that, and you wouldn’t devote this piece that professes to be about relationships to celebrating yourself and your milieu as though it speaks for the Chelsea shoppers’ or for mine. You’d think about the world you were in. The whole world, not just your part of it.

Some of the frustration of reading “Relationships” in the larger context of “Life After Trump” is the frustration of watching someone practice a mode that’s been outmoded as though it were still revolutionary. It’s part of Myles’s project as a poet to write from their own perspective. And it was likely groundbreaking or at least interesting when they first began writing: a way to speak to the experience and subjectivity of artists and creatives in late 20th-century America and make that real to those who did not know that world. Or a way to speak to those who wanted to join that world. It’s a poor mode now, in this time. Artists have long been integrated into the mainstream and the market—they’re no longer a vanguard. They’re not even people whom the mass media organs of the culture consciously turn to for a reflection of what life looks like now and what it could look like in the future. (Here, I’m thinking Sontag, Mailer, Dwight Macdonald, whoever—a small and biased set of examples, but the ones that come to mind.) The work of artists now feels like just another kind of content you might prefer to consume, just another piece of fodder for an identity (say, “literary person”) that you can espouse—and the presence of even critical artists and creatives is a marginal one that you, again as an individual consumer, can pay attention to if you like or just as easily ignore.

What’s more, in a time marked by widespread use of social media, everyone’s a poet of Myles’s type today. Everyone’s a relentless “I,” broadcasting their feelings and impressions of situations and history, talking about what everything and anything that happens feels like for them and what it means for them. I’m doing it right now! And I read magazines like Harper’s and Bookforum and the London Review of Books and more for a break from that mode—or a practice of it in which the “I” is a starting point, not the sum total. That is, when it comes to writing about the culture, I’m looking for writing that goes beyond the “I” to say something genuine about the world we’re in. Something that helps me understand that world better and then to change it.

#harper's magazine#eileen myles#a. s. hamrah#christian lorentzen#jane hu#charles yu#lauren oyler#elisa gabbert

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

various writings of interest

JUNE 2021

Are We Entering A New Political Era? - (Andres Marantz)

Social Media is Not Self-Expression - (Rob Horning)

“Being yourself” is inherently limiting. It is liberatory only in the sense of freeing one temporarily from existential doubts.

On Body Horror and the Female Body

The female body is a nexus of pain almost by design (that by-now ubiquitous line from Fleabag: “women are born with pain built in, it's our physical destiny”), but it is also potentially monstrous—an object traditionally subjugated, both for its presumed weakness and its perceived threat.

José Andrés Embraces The Chaos | HuffPost Canada Food & Drink

What Andrés was trying to do, though, was far more ambitious. He was trying to make humanitarian aid more human—responsive to the specific needs of people in crisis, rather than determined by massive systems and protocols.

The Golden Age of White Collar Crime

Those intuitions are correct: An entrenched, unfettered class of superpredators is wreaking havoc on American society. And in the process, they've broken the only systems capable of stopping them.

Behold, The Millennial Nuns

America started with a religious narrative—the city on a hill—and once you conceive of it, still, as a society grasping for religion, you see it everywhere.

25 Essential Notes on Craft from Matthew Salesses - Matthew Salesses, Literary Hub

Dickinson's Hair - Sarah Mesle, LA Review of Books

Specifically, women of color, are working to create the signs of femininity — the beautiful dresses, the meals — against which white women then wonder if they should rebel.

Life After Trump - Charles Yu, Mike Jaccarino, A. S. Hamrah, Eileen Myles, Judith Martin, Olivia Laing, Yinka Elujoba, Lauren Oyler, Jane Hu, Liane Carlson, David Owen, Christian Lorentzen, Christopher Beha, Harper’s Magazine

Not only must we continue living in a country that once elected Donald Trump as president; we must also continue living in a country where half the population wanted him to keep the role, a country where Trump may even seek office again.

Stacey Abrams Writes Black Women Into History - Shayla Lawson, Bustle

One reason I stan Abrams’ chick-lit career is how infrequently we get to talk about powerhouse Black women who express themselves in deeply feminine art forms, or about the relationship between art and organizing.

'Bridgerton' Isn't Bad Austen — It's An Entirely Different Genre - Claire Fallon, Huffpost

In the 1970s, novels typically featured brooding alpha males who took what they wanted sexually ― a narrative device, MacLean argued, for the fictional heroines of the time to have plenty of sex without being seen as loose and deserving of punishment.

'We Act Consciously on the Page and in Life': An Interview with Matthew Salesses | Hazlitt - Zan Romanoff, Hazlitt

And, of course, this is my bias, because all I do is write, and think about writing and talk about writing, but I think everyone who reads fiction should want to understand how it gets made. I loved that this book articulated some things I felt were missing in my own reading practice, in terms of reading mostly fiction by American authors and not understanding much about other narrative traditions.

The controversy over Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and trans women, explained

“I think that for people who have been wounded by gendering, it's quite accurate and understandable to say, ‘You don't share the same wound that I share,’” said Susan Stryker, associate professor of gender and women’s issues at the University of Arizona. “Where I start to have a problem with that argument is when it gets used to challenge trans people's access to gendered public space.”

TERFs: the rise of “trans-exclusionary radical feminists,” explained - Katelyn Burns, Vox

Gender-critical feminism, at its core, opposes the self-definition of trans people, arguing that anyone born with a vagina is in its own oppressed sex class, while anyone born with a penis is automatically an oppressor. In a TERF world, gender is a system that exists solely to oppress women, which it does through the imposition of femininity on those assigned female at birth.

Peggy Orenstein's “Boys & Sex” Is Groundbreaking, but Leaves Gaps for Queer Boys - Rachel Charlene Lewis, bitchmedia

Even the title of chapter four, “Get Used to It: Gay, Trans, and Queer Guys” suggests that these boys are something to get used to, something new and other. Her questioning of trans boys’ experiences seems to be largely shaped by her understanding of them as fascinating manipulators of patriarchy; those who were once victim to it when they “were girls” and are now “freed” of it as boys.

Luster, A Lover's Discourse, and the Portrayal of Whiteness - April Yee, The Paris Review

Whiteness cannot bear to be looked at. See the elaborate costumes of rioters who stormed the Capitol, or the hoods their predecessors wore.

How a Little Book About Hating Men Sparked a Firestorm in France - Sarah Moroz, Dailybeast

Misandry has a target, but it does not have a list of victims.

A Challenge You Have Overcome - Allegra Goodman, The New Yorker

"1984" Keeping in Mind that I've Never Read It - Ellis Rosen, The New Yorker

Pixar's Troubled "Soul" - Namwali Serpell, The New Yorker

But even recent, more ostensibly race-conscious works (see again “Watchmen” and “Lovecraft Country”) play with this theme in sometimes disturbing ways, as though unable to resist making white people the hero of blackness.

The white desire to get inside black flesh is absolved as an empathy exercise. Blackface gets a moral makeover. It’s telling that, in most race-transformation tales, the ideal is presented as a white soul in a black body.

A Parisian Writes Her Revenge - Lauren Collins, The New Yorker

According to the sociologist Pierre Verdrager, the book’s success marks “a major turning point” in the perception of pedophilia in France. “merci, vanessa springora,” read a sign that the feminist collective Les Colleuses pasted on a wall in Paris last year.

The Generic Latinidad of "In the Heights" - Frances Negrón-Muntaner, The New Yorker

The big point of this big film is to seek comfort in the small, and that also puts limits on the characters’ political imaginations. They assert their dignity “in small ways” and “little details,” trusting that everything will be fine if you just have a “sueñito,” a “little dream.” This belief promotes the fiction of the individual pursuit of happiness, rather than exploring a complex politics that brings broader change. It also links to the class politics of the film. Although the emphasis on hard work is meant to combat stereotypes of laziness, “In the Heights” narratively attempts to resolve deep structural problems with improbable solutions, such as small-business ownership, a lottery ticket, or “paciencia y fe” (“patience and faith”). These ideas are especially hard to take from a Hollywood movie or from Miranda, who, at this point in his career, is hardly an exemplar of thinking modestly, but rather of aspiring to be everywhere doing everything, including politics. He does not seem to believe in el sueñito, but in el sueño grande.

Living with a Visionary - John Matthias, The New Yorker

Of Progressive Bookselling, Past and Future - Lucy Kogler, Literary Hub

Amazon. Who cares? Really, who cares. It came, saw, conquered, exploited, demeaned, demonized, distracted, shat upon its workforce, the postal system, small business owners, and stayed, only to succeed in a most robust way. And so a countervailing (almost anyway) instrument was created: Bookshop.

Reading the Literature of the Bicycle As I Learned to Ride One - Rhian Sasseen, Literary Hub

Something curious happens when you begin to spend an increasing chunk of your time navigating your city in this way. You begin to approach its ecosystem differently, realizing how fundamentally the details you notice might shift depending on what form of transport you happen to be using that day. I find it difficult to daydream on a bicycle in the way that I can daydream on a long walk, but in exchange there is an awareness of the body, and an awareness of the roads, that was previously missing.

The Sexual Double Standards That Led to the Baby Boom—and ‘Girls in Trouble’ - Gabrielle Glaser, Literary Hub

Embracing Imperfection: On Writing in a Foreign Language - Kaori Fujimoto, Literary Hub

I began to focus more on being “me” in my writing. While working on drafts, I looked squarely at simple facts about myself relevant to the work at hand, including being a native East Asian, a person who had an unhappy childhood in a dysfunctional upper middle-class family, a daughter of parents who experienced war, and a woman with no interest in raising a family. I acknowledged the experiences, one by one, heartwarming or heartbreaking, that these qualities had brought me and embraced them. I fully embraced them so that I would recount them in my truthful voice. I have never been perfect, nor can I ever write anything perfect. But I can always be authentic. I realized that being real, rather than flawless, is the best thing I can do for myself not just as a writer, but as a person.

30 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It’s interesting to note that Burt Reynolds and Mark Wahlberg both disavowed Boogie Nights years after it came out, saying they wished they had not been in it. Since it’s the film that rescued them at crucial points in their careers, that really says something about Hollywood. After all, these are actors who also starred in Cannonball Run II and Transformers: The Last Knight, films they didn’t renounce. If there is something essentially non-Hollywood about Anderson, he has learned to tamp it down. He’s no longer the interviewee who once wished testicular cancer on fellow director David Fincher.

A.S. Hamrah, Inherent Nice: Paul Thomas Anderson thrives in toxic Hollywood

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A nicotine fiend and a coffee addict who mixes existential dread with sadomasochism in all-American settings, [David] Lynch is that rare director who makes subversive films without a chip on his shoulder, seemingly without any will to provocation. He is at home with his neuroses and obsessions. His secret is that he proceeds as though he is acting from the most impossible condition of all: normalcy. While directors like David Fincher and Lars von Trier explore similar terrain with grim determination, only Lynch enters nightmare worlds like the Eagle Scout he was, as inquisitive about the depths of human psychology as he is about bugs and twigs.

A. S. Hamrah in his 2016 essay on David Lynch: The Interpretation of Screams

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some Notes on A. S. Hamrah

A lifetime ago, I thought it’d be rewarding to teach A. S. Hamrah’s “A Better Moustrap” to first-year students struggling through their second semester of basic comp. I wanted to wow them with Hamrah’s heedless deployment of unsettling theses, argued crisply and irreverently, in an essay that supplies a plausible solution to its concerns (a rarity among most rhetorical appeals, whose authors left my students stimulated but empty-handed). Very in the vein of “A Modest Proposal,” “Mousetrap” confronts a social ill—fetish videos where women crush small animals to death under their Stilettos—yet proposes a non-ironic salve: “crushies,” where “the must-have plush-toys of the Christmas rush will be smashed underfoot.” Most of my course was based on weird internet shit, which I thought (I still think) mostly anyone can appreciate, especially the young. “Mousetrap” is full of that weird-internet-shit jouissance.

“Reading this is like eating your favorite food,” I told the class. “You’re just gonna shovel in ideas. They’re all delicious. Eh, they’re pretty weird, too. But it’ll be fun.” It wasn’t fun. Nobody read the essay. Moving through its arguments, in front of twenty-five nineteen-year-olds and a few grandmothers, was embarrassing. I had to dissect Hamrah’s great takes on crush video culture, his movements through film history, his appraisals of Mickey Rooney, then his wider and, to me, scintillating prognostications on American adulthood—an adulthood most everyone in the classroom (accepting the grannies) was soon to inherit—totally alone. “Do you watch these videos?” one student asked. “Then what’s your fetish?” asked another. “Bryson fucks books!” became the consensus. (“I fuck your dads!” I thankfully did not say but very much wanted to. I was a coward; this partially explains why no one bothered to complete my assignments.)

Flying solo—or falling sans parachute, as the case may be—through Hamrah’s film criticism and cultural reportage of the last decade has probably been a shared experience among his far-flung admirers. Finding his byline in Bookforum or the obscure domain of the International Federation of Film Critics or mirrored pages from the defunct Hermenaut was usually the result of a periodic Google search. If he appears more regularly now, and more regularly in prestige venues, that’s the fault of n+1, where he’s contributed reviews tri-quarterly since roughly 2008.

Indeed, it was Hamrah’s initial, online-only contribution that inspired so much ardor and devotion. “Oscars Previews” provided bright, bursting capsules—the gleeful bitchery of a best friend's phone call. Apparently this quality was transliterated from its material creation, when he reported the piece to his editor, Keith Gessen, over a phone, after complaining he didn’t have time to write the thing. Each entry in this salvo (none are more than a hundred or so words) lands with a zinger. They have the polish of a joke, featuring a setup, some reinforcement and then a payoff. He even plays some of his capsules against each other as callbacks. The entirety of Hamrah’s entry on Michael Clayton reads: “There was a lot of driving in Michael Clayton. I like driving in movies but after a while Michael Clayton started to seem like a car ad—though it showed how a car ad can be liberal. That’s a message for our times.” The wit is authoritative, hypnotic, dismissive. The taste behind these pronouncements felt sui generis, and the criticisms brief enough to be dispatched verbatim without attribution. I was a senior in college when I first read Hamrah. I had a busy season of parties at professor’s houses and dined-out on his opinions for weeks.

This is not to say Hamrah only works when you’re young and grasping for style. But I do think it’s evident now that his short forms are the seedbed for his long form successes, paper sketches for the larger canvas. When you read enough of Hamrah’s capsule reviews, you get the sense he’s reporting exactly (or only) what fits into his little joke, sometimes you can even hear him reaching for his beats. When you read a whole book of them, you get the sense Hamrah’s less interested in the works under review than in his performance of reviews, his performance of freedom and audacity.

—

The Earth Dies Streaming, apart from film writing, is a log of Hamrah’s fascination with his persona, his brand of humor and arch sensibilities. He’s not exactly a curmudgeon—he wants readers to know he’s tried too many drugs to be a curmudgeon (comparisons to acid trips crop up, as does “bad speed”)—and he’s not exactly an academic (despite his Ivy League bona fides as a corporate semiotician)—and he’s not even a movie reviewer in the jejune, crass, sell-out way so many movie reviewer must be in today’s enfeebled, saturated, and deeply compromised market (he tries “to never include anything in [his] writing that could be extracted and used for publicity”). This is where I trot out a gif of Amy Poehler playing a Cool Mom in Mean Girls. Hamrah’s bobblehead offers virgin daiquiris to teenage cineastes. “I’m not like a regular film critic,” he says, “I’m a cool film critic.” The tits, the wink, the velour sweatsuit.

Other irritations. Hamrah’s insistence on the inferiority of animated films and his churlish dismissal of Miyazaki’s contributions to the medium’s history. He’s always on accident catching some part of a children’s movie—on an airplane, in a public clinic—and using these unsatisfactory experiences to comment on the aesthetics and advancements of animation at large. It’s a hobby horse he flays as often as Adorno assaulted jazz, and (to both their credits), slightly adorable for how insistent and under-thought. If only, as he does in “Jessica Biel’s Hand,” he would immerse himself in the backlog of lauded animation from this century and the last, he might, for once, be able to say something interesting about it.

Hamrah’s stance against feature-length animation is nearly as looming and placeless as his stance against other films critics, whom he evidently reads closely but can never be bothered to cite. His essays are peppered with a dreaded sea of bought-off weekly reviewers whose pedestrian tastes frustrate him. This, despite the regularly insightful, playful, and overall helpful criticism of David Edelstein and Emily Yoshida at New York; Dana Stevens at Slate; Manhola Darghis at the Times; Justin Chang in Los Angeles; and the fairly dour takes of Peter Debruge in the industry’s digest, Variety. Hamrah alludes to David Denby’s work in Streaming’s introduction, then names him outright in a later capsule review of Little Children. Otherwise, your guess is as good as mine as to with what critical consensus Hamrah finds his views out of alignment. These are critics and journalists who, obliged by deadlines, report weekly on their film-going habits. That they have new things to say even once a month is a miracle, but that they do so four to ten times a month is frankly incredible. (It must be evident that I’m a fan of movie reviews and film criticism. I work an office job where between menials I find intense delight and distraction in the work of daily reviewers, and I carry around with me an ungainly amount of knowledge regarding box office performances and future releases that in all other ways I have no interaction: I go to the movies maybe three times a month, often by myself, and often I see low-brow flicks. Last weekend I saw the third How to Train Your Dragon movie; the weekend before that, Isn’t It Romantic; a weekend before that, Roma. I saw these movies on the advice of daily reviewers, and Roma only after reading Caleb Crain’s celebration of it.)

I volunteer Richard Brody and Christian Lorentzen as Hamrah’s contemporary intellectual kin, with caveats. Brody’s work is too mystical, too mythical to properly critique his subjects, and his symptomatic readings, which border on the Lacanian in terms of the extraneous and deranged, become hulking apertures that always overtake whatever work is under discussion, squashing them. Also he is never, ever funny in his reviews. Brody is a curmudgeon, and what he criticizes rarely appears in the films themselves but float around the films’ receptions, financing or forebears, and when he ventures into specifics—a film’s lensing, its sound, the actors and their acting styles—his descriptions become ridiculous. Lorentzen, as with his book reviews, writes to a word count. (There is no other reason for the amount of tedious plot summary in a Lorentzen take-down.) If Hamrah sounds like these critics, it may be because all three are careful in their dissents to let the filmmakers know they think they’re complete assholes. When these three do find praise for a work, it’s the entirely appropriate object of adoration, art-house and independent, or, gotcha!, a studio event they appreciate for more correct, more interesting, and more nuanced reasons than everyone else.

What sets these critics apart from the daily reviewers I listed above, may be the daily reviewers’ capacity to surprise and be surprised. Perhaps they saw a movie with a daughter and her friend; they appreciated a family flick in context; they were caught unawares by stray scenes in a larger, unsuccessful work, and appreciated glimpsed wisdom. They have hope yet for a return to better forms. These reviewers are flexible and receptive; they are as likely to be charmed as they are to be chagrined. Even when Brody, Lorentzen and Hamrah are surprised by the quality of a work, they take it as an affront to their sensibilities and bridle, like horses suspicious of an open gate. Why were they not warned? Why should they trust this development? Their reflexive, ingrained annoyance, occasionally flowering into high dudgeon, fills their actual reviews with foregone conclusions. One does not visit their writing for news, or for new takes, for synthesized connections, or revelations of form. One visits for the comforting familiarity of a flagging standard—“a continuity of aesthetics that [has] become an aesthetics of continuity,” if I’m remembering the St Aubyn phrase correctly.

Criticism this entrenched in its own personality ends up toothless. It’s why Renata Adler, for instance, will be remembered for her reporting and not her film criticism. Despite its bite—and it’s quite biting—it rarely leaves a mark. Hamrah never cites Adler—nor do I think he will. His prose and her prose are rather too alike. He must sense the comparison coming, and dislike it, because Adler is not particularly well informed on film and filmmaking. Her amateurish moonlighting grated in 1968, and it grates now, but only for its prosumer-level expertise. Her prose (like Hamrah’s) remains indelible, deadpan, and addictive. When I recall the subhead to Kyle Paoletta’s appreciation of Hamrah, “Always On: A. S. Hamrah’s film criticism is a welcome corrective in an outmoded field,” I consider Adler’s own attempts at the form, as a corrective. And I find them contiguous with other platforms discussing same, places like Slate, Twitter, and The Ringer’s Exit Survey, which preempts the leap from hot take to tweet. (Q: “What is your tweet-length review of Venom?” A: “What if All of Me (1984) but action and also tater tot–loving aliens?”) What I’m saying is this: Hamrah’s form is not novel. His tone is not novel. His writing is, however, very convenient (brief, digestible) and entertaining, and he’s been adding more personal atmosphere of late.

So the named lodestars in Hamrah’s critical firmament: Pauline Kael, Susan Sontag, Jonathan Rosenbaum, J. Hoberman and Manny Farber (to whom Hamrah pens an exceptionally sweet and informative essay). Hoberman, the only critic still alive among these titans, shares Hamrah’s acid tongue and penchant for political excavations, while doing his readers a courtesy by assuming not all of them attend film festivals or live in limited-release area codes. The same semester I taught “A Better Mousetrap,” I taught Sontag on sci-fi movies and Hoberman’s seminal “21st Century Cinema: Death and Resurrection in the Desert of the (New) Real” (later to become his book-length essay, Film After Film). Hoberman can be as tart and irreverent as Hamrah, but he’s not above recounting plot summaries. He’s both a guide and a rebel. I suppose, following my own argument, if in fact I’m making one, this makes Hoberman the better critic—a classification that would not hurt Hamrah’s feelings. (This would hurt very few film critics’ feelings.)

—

Very little of the above matters. I had hoped to answer why, then I got bored (then I had to go to work; after that, I had to design a booth for a marketing expo in London; then I lost the thread). When I was in Brooklyn last December, I dropped into the Spoonbill on Montrose. The first book I bought on my second time in New York City was Hamrah’s The Earth Dies Streaming, and I carried it about like an obsessive as I made my way by foot to Prospect Park. I devoured it in a few days. I devoured it again on the plane ride back to Chicago. And I’ve read all the capsules before, and most of the essays—they’re usually posted in front of paywalls. If I quibble with Hamrah, it may be because he’s made me a better writer, and surely a better thinker, yet I found that I disliked my own dismissiveness and superiority, my own rigidity. If I can name my influences, I thought, I can break from them. But this is unso.

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Yes, sacks of fat, for he is the Whale, puking on his shirt, sobbing alone in his apartment in the green-brown murk of contemporary cinematography. And the whale is also Moby-Dick, and the whale is Herman Melville, too, who was using the metaphor of the whale to hide his own whaleness. Are we all the whale? I don’t think so. Yet Darren Aronofsky’s film of this joyless play was a hit, so I guess it touched something in the moviegoing public. It had to use a bodega claw to do it because it couldn’t get off the couch, but it touched them.

A. S. Hamrah

1 note

·

View note

Text

Favorite Six Books I Read In 2022

1. Stay True - Hua Hsu

2. The Trees - Percival Everett

3. Journalist and the Murderer - Janet Malcolm

4. Mating - Norman Rush

5. In the Eye of the Wild - Natasja Martin

6. The Right to Sex - Amia Srinivasan

Honorable mention to The Earth Dies Streaming by A. S. Hamrah

0 notes