#a huge part of our current biodiversity crisis is in fact the fact that we *don't* use the land like we used to

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Resolutely not reblogging a post about the UK biodiversity crisis to point out that drastic declines in biodiversity in the last 20-100 years do not, necessarily, mean that the entire history of human cultivation of nature here is catastrophic. Like, I get the point the person was making and I also think that the 'we made this green and pleasant land' rhetoric is usually thinly-veiled nationalist chauvinism, but also please think about the statistics you're using.

If your stats all point to the major damage being in the last century or two, this relates to industrialisation, industrial farming, power consolidation, and un/deregulation, not the activities of ordinary farmers 500 years ago or whatever. Therefore, it's not actually countering the points the 'green and pleasant land' chuds are talking about.

#a huge part of our current biodiversity crisis is in fact the fact that we *don't* use the land like we used to#we invested in industry artificial fertiliser and nimbyism instead#and like yes those were organic products of our history#but the strand of history that will be most instructive is the history of power and power relations#most people here for most of history/prehistory existed in a reasonable equilibrium with the natural world#were we ecosystem engineers on the level of the indigenous people of the americas? absolutely not#but that's a fairly high bar to clear they were/are extremely good at it

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

World Green Roof Day

See if you can create an environmentally-friendly, plant-filled space on your roof for Green Roof Day. Snap some pictures and spread the word about its benefits.

Have you heard of World Green Roof Day? If not, you’re missing out!

Towns and cities all over the world are going green to clean up their carbon footprint and adapt to climate change. Not only do green roofs benefit everyone, they benefit small wildlife, and that’s something that we should all be celebrating! This celebration of green roofs is a global thing, and whether you are in business or not, you can still celebrate going green.

Whether it’s a bike shed or a bus stop, the roof of your new extension or your home office, you can still enjoy a beautiful green roof and celebrating it is going to be more than encouraged. Every World Green Roof Day, people the world over are encouraged to look out of their window and check for roofs that are perfect candidates for going green!

What are green roofs?

A green roof is also known as a living roof. It’s a roof space that facilitates shrubs, trees, vegetation and pretty spaces designed to be colourful and aid the environment.

Why should green roofs be celebrated?

We are in a climate emergency, and we can’t get away from that fact. Green roofs are going to be a big part of the solution. Green roofs are not a new concept, but they may be newly received from those who aren’t aware of what it all means for them.

The very first green roof policy came about in 1979 in Germany. Green roofs are particularly popular among those in urban planning in Europe, but the rest of the world needs to catch on – fast – if we are to do something about the current climate crisis.

In the bigger cities in America and the UK, rooftop gardens and greenery are becoming more and more popular, with London leading the charge in green rooftop oasis spaces. There is a great deal of value and environmental benefits in green roofing, and cities across the world should take them up to ensure that they are helping the rest of the world, too.

There are different types of green roof design, from intensive and biodiverse to extensive. Some green roofs are domestic and others commercial, some on flat roofs and others pitched. The chance for amazing design is huge and you can improve air quality, collect and control rainwater runoff and deliver improvements and value to each building. There are huge benefits to having a green roof, so let’s check those out!

Benefits of Green Roofs

Green roofs are very popular in urban areas, so when it comes to World Green Roof Day, it’s important to know the benefits of having a green roof. Let’s dive in!

Replacing Green Spaces

When you live in a city or built-up area, you notice pretty quickly that the rise of high-rises and concrete is rapidly overtaking green spaces. With much of this green space reducing in size and frequency, green roofing has become the next best option. We need vegetation and greenery, trees and better oxygen. With the spaces gone, green roof gardens can replace some of the lost greenery that we rely on. Our birds, insects and other wildlife rely on them, too.

Monitoring Rain

Roof gardens retain rainwater and it’s easier to manage storm water as a result. Urban areas have hard slabs and concrete as the major materials, and as such, rainwater run-off can cause flooding. Without proper management, this water becomes a hazard in urban places. Green roofs can reduce the load and retain that water.

A Peaceful Place

A rooftop garden is one of the best things to come out of urban areas. It’s a place that provides tranquillity and calm and it’s a jewel in the crown of a city. Green roofs provide a great space in which to relax, and they offer the perfect escape from the hustle and bustle of the city.

Aesthetics

Grass and plants always make a home look better, and a lush garden on top of a roof just makes the house look beautiful. It works for an office building, too, and a green roof works to brighten up an otherwise grey space.

Green roofs can be big or small and they work to improve air quality, cool the urban environment and insulate the buildings. They work to boost the wellbeing of others, too!

History of World Green Roof Day

World Green Roof Day was founded by Chris Bridgman & Dusty Gedge; veterans of the sustainable living roof arena. Each year, they’re devoted to helping World Green Roof Day educate others on the benefits of green roofs to our climate, cities and wellbeing.

The founders are also board members of the Green Roof Organisation, a UK trade body that’s responsible for the green roof code of practice. By celebrating green roofs, there is hope across the globe that we can all come together and enjoy green spaces and all they have to offer.

We need to continue to act to ensure that they are well-maintained, and World Green Roof Day allows you time to celebrate the efforts put in by all and the benefits that green roofs bring us.

Fun Facts

Did you know…

Green roofs can reduce the flow of storm water from a roof by up to 65%.

Protected from ultraviolet radiation and changes in temperature, green roofs can last two to three times longer than standard roofs.

42% of the total market in the UK for green roofs is in London. The more dense the urban environment, the more greenery up top you can expect!

The Central Activity Zone of London (the fancy word for “heart of the city”) had green roofs covering 290,000m2 as of 2017!

How to celebrate World Green Roof Day

Get your cameras ready and start snapping. Use social media to discuss the green roof you have going on, or your favorite roof-top gardens you’ve seen while out-and-about.

Tell your town pages, your city billboards and your local politicians why you think green roofs are important. If you haven’t seen anyone talk about them in your area, it’s up to you shout it from the proverbial green rooftops!

Source

#Woodward's 43#Vancouver#Eugenia Place#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#architecture#summer 2023#2012#British Columbia#Canada#World Green Roof Day#6 June#WorldGreenRoofDay#Tyresta National Park and Nature Reserve#Sweden#Norway

0 notes

Text

The causes and impacts of the melting Himalayan glaciers

The Himalayas is a mountain range that’s home to many of the world’s highest peaks. Passing through India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, China, Bhutan and Nepal, this incredible span of geography is an important cultural and ecological location. However, climate change threatens the area, and the impacts of the melting Himalayan glaciers could be devastating.

We explore why this mountain range is so fascinating and essential, looking especially at its many glaciers. We also explore why these glaciers are melting and what the results of the changing Himalayan climate could mean.

An introduction to the Himalayas

First, let’s take a quick look at the mountain range itself. It’s a place that has significance to many and is firmly rooted in popular culture. However, given its size and scale, it’s often not understood especially well.

What are the Himalayas?

The Himalayas are a mountain system in South and East Asia that spans around 1,550 miles (2,500 km), running west-northwest to east-southeast in an arc. This huge geographical range means that climates in the Himalayas vary between humid and subtropical in the foothills to dry desert conditions in the higher reaches.

The Himalayan region is home to over 50 million people, yet an estimated 2 billion people rely on waters from Himalayan glaciers for drinking, energy, agriculture and more. Those who live there have their own distinct cultures, and there are various places of religious significance.

The Himalayan mountain range is also a biodiversity hotspot, home to a vast range of flora and fauna, including species such as snow leopards, Bengal tigers and one-horned rhino.

Where are the Himalayas?

As we’ve mentioned, the Himalayas covers many hundreds of miles. As well as stretching across the northeast portion of India, they also pass through Pakistan, Afghanistan, China, Bhutan and Nepal.

According to Britannica, the mountain range itself starts at Nanga Parbat (26,660 feet), in the Pakistani-administered portion of the Kashmir region, and ends at Namjagbarwa (Namcha Barwa) Peak (25,445 feet ), in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China.

How were they formed?

By mountain standards, the Himalayas are a relatively young range. They began to form around 40 to 50 million years ago when tectonic plate movement drove the landmasses of India and Eurasia together.

The pressure of the collision, and the fact that each continental landmass had about the same density, meant that the plates were thrust skyward, contorting the impact area and forming the jagged peaks of the Himalayas.

The modern Himalayas

Today, the Himalayas remain a culturally and environmentally important region. Many different people live in the Himalayas, and it’s a source of life for many of them. However, in recent years it’s also become a popular tourist destination.

Although tourism brings a range of economic and business opportunities and jobs, there are downsides. The effects on the environment, particularly with issues such as pollution, mean that the biodiversity of the area is under threat.

University of Exeter Climate Change: The Science

University of Exeter Valuing Nature: Should We Put a Price on Ecosystems?

University of Exeter Tipping Points: Climate Change and Society

The Himalayan glaciers

Incredibly, there are 32,392 glaciers in the Himalayas. Together, they are part of intricate geographic and climate systems. Let’s find out more about them.

What is a glacier?

As we explore in our open step on the subject, glaciers are large bodies of ice, originally made from snow that accumulates over long periods of time. They vary greatly in size and can be as small as a football field or stretch for hundreds of kilometres.

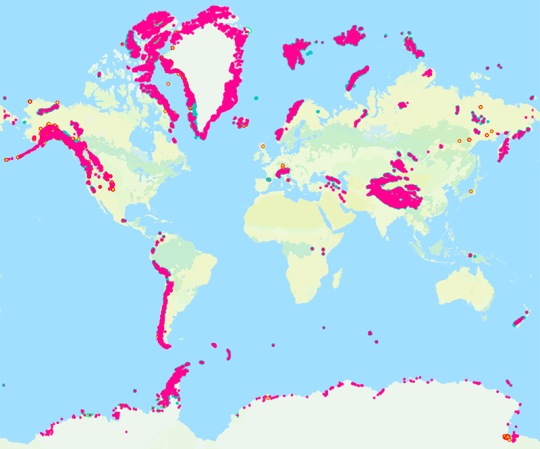

Based on this, we can say that the definition of a glacier is a body of ice formed from the compaction of snow that moves downhill under its own weight. As you can imagine, for such a process to work, sustained low temperatures and snowfall are needed to create and maintain glaciers, meaning that they’re found either at high latitudes (the polar regions) or high altitudes (associated with mountains).

This map is generated from data provided by the Randolph Glacier Inventory. You will observe that ice is either found at high latitudes – i.e. the polar regions – or high altitudes – i.e. associated with mountains. Image courtesy of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, generated using data from the Randolph Glacier Inventory, GLIMS.

Why are they important?

So why do glaciers matter? Well, they play a central role in the world’s water systems, contributing to various elements of life. Glaciers:

Provide drinking water. Approximately 75% of all of the world’s fresh water is locked up in glacier ice. Glacial melt provides drinking water for people in various places around the world, including the Himalayas.

Irrigate crops. Throughout history, countries have used melting glaciers to water their crops and power their agriculture. Even today, communities still rely on glacial melt in this way.

Generate power. It’s possible to use the meltwater from glaciers to power hydroelectric dams, providing electricity for the area.

It’s not just the immediate area that feels the impacts of glaciers. In the Himalayas, for example, the Indus, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra Rivers all originate from glaciers. These rivers provide water for countless millions of people.

The glaciers in the Himalayas

The Himalayas are home to the third-largest deposit of ice and snow in the world. Only Antarctica and the Arctic have more. These glaciers feed some of the planet’s most important river systems, directly and indirectly supplying billions of people with water, energy, and incomes.

Clearly, the Himalayan glaciers are an essential part of life for the eight surrounding countries, as well as further beyond. However, new studies have shown that the glaciers in the Himalayas are melting at an alarming rate. The consequences of this melt could be disastrous.

Why are the Himalayan glaciers melting?

The Himalayas in India and beyond have come under close attention in recent years. Several recent studies have shown that the situation could be much worse than originally feared. One study, in particular, found that if CO2 emissions are not cut drastically, around two-thirds of the Hindu Kush-Himalaya (HKH) region glaciers could disappear.

Glaciers in the Himalayas lost billions of tons of ice between 2000 and 2016, double the amount that took place between 1975 and 2000. Rising global temperatures are to blame – the result of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions.

Air pollutants from unclean energy sources are also contributing. The dirty air then deposits black carbon dust on the ice. This dust means the glaciers absorb more heat and thaw more rapidly.

You can read more about measuring glacial change in our open step and learn about climate change and society with our online course.

The image above is a satellite image showing multiple retreating glaciers in the Bhutanese Himalayas. As a consequence of this retreat, proglacial lakes form in front of these glaciers.

The impacts of melting Himalayan glaciers

There are real concerns about the potential impacts of the melting glaciers in the Himalayas and beyond. Here are just some of the devastating effects of glacier loss on the surrounding regions:

Increased flooding. As more meltwater enters the water system, proglacial glacial lakes form. However, these lakes are often unstable, and when the dams break, they can cause catastrophic glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs). Similarly, more water in the glacier-fed rivers increases the risk of flooding.

More extreme weather events. With more water and a warmer global temperature, the risk of extreme weather events increases. Scientists have already started to notice changes in temperature and precipitation extremes, for example.

Changes in the monsoon. In Asia, the monsoon helps to support the livelihoods of millions of people. The annual rains are crucial to agriculture and water supplies. As global warming changes monsoon patterns, the risk of flooding during this season increases.

Lower agricultural yields. Global warming means that snow and glaciers melt earlier in the year, leading to floods in spring. However, by summer, when crops need more water, volumes of water are decreased. As a result, agricultural yields are lower, arid zones increase, and fishing in the region is affected.

Changes in energy production. Further downstream, the volume of water in dams may impact the production of hydroelectricity.

Ultimately, the melting Himalayan glaciers could cause real harm to the livelihoods of untold millions. Whether it’s changing weather patterns, extreme flooding, changes in food and energy production, or unpredictable water supplies, the risks seem very real.

University of Groningen Making Climate Adaptation Happen: Governing Transformation Strategies for Climate Change

University of York Tackling Environmental Challenges for a Sustainable Future

University of Exeter Climate Change: Solutions

How can we improve the situation?

So, the current and future danger of melting glaciers is evident. But what can we do to improve the situation? In reality, the only real solution is to prevent further global warming. There are many climate change solutions, and many of these focus on reducing your carbon footprint.

Although individuals can take steps to reduce emissions, governments and corporations need to make far-reaching changes to policies and practices. As we stand on the edge of a climate crisis, there is much work to be done to improve the situation.

Final thoughts

The Himalayan glaciers are crucial not only to the surrounding regions but also to the billions of people whose lives are affected by them. Recent global warming and climate change have seen these glaciers melting at an unprecedented rate, and the effects are devastating.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Himalayas glaciers, the environment, and climate change, we have a wide range of free courses available that can help. Our course on tackling environmental challenges for a sustainable future is an excellent place to start.

The post The causes and impacts of the melting Himalayan glaciers appeared first on FutureLearn.

The causes and impacts of the melting Himalayan glaciers published first on https://premiumedusite.tumblr.com/rss

0 notes

Text

Witnessing a Pandemic and Some Reflections from the Ancient Past

by Tevfik Emre Şerifoğlu, ANAMED Senior Fellow (2019-2020)

A view of İstiklal Caddesi from ANAMED before the pandemic.

We are all going through extraordinary times. The Covid-19 pandemic has forced us to change our daily routines and lifestyles and adapt to a mostly home-based life supported by digital technology that enables us to continue working and keep in touch with friends and colleagues. For us as ANAMED fellows, this had a relatively devastating effect as we suddenly lost a lively research environment which we all enjoyed and from which we all benefited at a level one rarely experiences. Being a residential ANAMED fellow also meant living in Beyoğlu and experiencing the bustling and cheerful life along İstiklal Caddesi at the social heart of Istanbul, which used to be a place full of people almost 24 hours a day. İstiklal and parts of Beyoğlu surrounding it are now more or less deserted except for the members of the working class, who struggle to keep the service industry functioning as they have noother alternatives. Staying or working from home is sadly not an option for them, and life continues as it has always been.

Although this is the first time we are directly facing a pandemic in our lives and witnessing its devastating effects, we all knew that epidemics and pandemics took the lives of entire populations, caused socio-economic systems to collapse, and left deep marks on the cultural memories of people throughout history across the globe. As my research focuses on the Ancient Near East, I decided to look back at how deadly outbreaks in the region’s distant past—the earliest attested written records of epidemics we can refer to—were described, hoping that we can relate to them in these hard times.

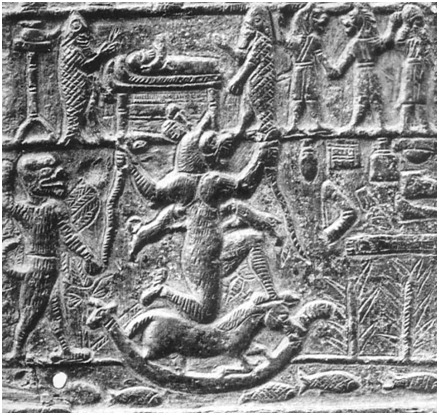

Ordinary people did not mean much to the ruling classes of ancient states of the Near East. They were vital for the economic and socio-political systems to function, but they were more or less seen as masses that were created to serve the political and religious elite, work all their lives under severe conditions under the pretext of obeying and serving the gods, and had no rights whatsoever. Once an epidemic hit the land, these people deemed unimportant were the first to become victims, but losing too many of them meant economic depression and, in some cases, the collapse of the whole system. People did not really know how deadly bacteria and viruses functioned, and these diseases with such huge impacts could only be explained with reference to some sort of divine intervention or the wrath of gods, to be more specific. It was widely believed that supernatural beings spread such diseases, in a way possessing people and causing them to die, and so people sought the help of other supernatural beings or deities in these situations.[1] So instead of wearing masks and adopting “social distancing,” they prayed, conducted rituals, and wore protective amulets, hoping that these would keep the malicious beings that brought diseases away from them.

Detail of an ancient Mesopotamian amulet showing a sick person, priests, and a demon.

Various Sumerian texts from the end of the third millennium BCE from southern Iraq mention symptoms of diseases and possible epidemics.[2] These texts talk about people having difficulty breathing, and having contorted faces and twisted muscles because of diseases that spread with the wind like a storm, in one case originating from a distant land and in another asking it to return to its home. People cry with pain and feel helpless as they have no remedy and lose all their loved ones. The texts also refer to economic problems that made things even worse, such as famine, another calamity people had to face at these times of trouble. These epidemics were defined as destroyers of cities, causing masses to die.

The earliest mention of an epidemic from Turkey can be found in Hittite texts from central Anatolia. King Murshili II talks about a 20-year epidemic in the 14th century BCE that took the lives of two kings and many subjects, blaming Egyptian prisoners as the source of disease.[3] Based on recorded symptoms and analyses of human bones, some scholars suggest the concerned disease was malaria, but others have suggested tularemia, bubonic plague, or smallpox.[4] In fact, it was understood that during the same period there were also outbreaks in Egypt, and some think that the sudden shift of the capital to Amarna, a newly founded city with a purely administrative and ritual purpose, which was abandoned not long after being established, is directly related to an epidemic, in a way helping the elites and the upper bureaucracy to isolate themselves during that period.[5] Based on archaeological data and ancient textual sources, it was claimed that this was actually a regional epidemic that affected most of the Eastern Mediterranean world during this period.[6]

Although some scholars would like to label these outbreaks as the main causes for the collapses of the Sumerian city-states and later the Hittite Empire, the evidence implies that there were other reasons like political, economic, and more importantly climatic events, to which the states and the people could not quickly adapt, which resulted with the weakening of the systems and their final collapse. In any case, epidemics were one of the main causes of socio-political and economic disruptions and resulted with change in positive or negative ways.

Today we know the mechanisms of how bacterial and viral infections spread and affect our bodies, and we try to avoid contamination with physical distancing and with an adequate level of hygiene. However, many still would like to believe that epidemics are linked to some sort of divine intervention, like in ancient times. Besides being a result of certain ideas that belief systems dictate and in some cases being an outcome of old superstitions, I think this is also a sign of guilt as people are well aware to what extent we have damaged the ecosystem of our planet and feel that the current neoliberal capitalist system, which is exploiting and devouring the planet’s resources and all beings inhabiting it, is not sustainable. The connection between the human-imposed climate crisis and the pandemic seems to be strong and makes us all think that the global socio-economic system cannot continue to exist in the way it used to function.[7]

İstikal Caddesi these days.

It is now the end of spring and the weather is beautiful. As we approach the end of our fellowship period at ANAMED, İstiklal Caddesi is getting more and more crowded, with many shops opening after two long months. People hope that things will get back to “normal” and this nightmare will be something of the past, but many studies predict something different. The Covid-19 pandemic most probably will not cause systems to collapse but, considering the level of distrust it has resulted with, we are surely to witness drastic changes and will be living in a very different world after it is over. Unfortunately, whether this will be a better world or a darker version of what we currently have is something hard to guess in this time of uncertainties.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Mujais, S. 1999. “The Future of the Realm: Medicine and Divination in Ancient Syro-Mesopotamia” American Journal of Nephrology 19: 133-39; Bácskay, A. 2017. “The Natural and Supernatural Aspects of Fever in Mesopotamian Medical Texts” in S. Bhayro and C. Rider, eds. Demons and Illness from Antiquity to the Early-Modern Period. Brill: Leiden, 39-52.

[2] Niazi, A.D. 2014. “Plague Epidemic in Sumerian Empire, Mesopotamia, 4000 Years Ago” The Iraqi Postgraduate Medical Journal 13(1): 85-90.

[3] Singer, I. 2002. Hittite Prayers. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature; Pritchard, J.B. 1955. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET), ANET 395. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[4] Smith-Guzmán, N.E., J.C. Rose and K. Kuckens. 2016. “Beyond the Differential Diagnosis: New Approaches to the Bioarchaeology of the Hittite Plague” in M.K. Zuckerman and D.L. Martin, eds. New Directions in Biocultural Anthropology. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 295-316.

[5] Kozloff, A.P. 2006. Bubonic Plague in the Reign of Amenhotep III? KMT-A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt 17(3): 36–46.

[6] Gestoso-Singer, G. 2017. Beyond Amarna: The “Hand of Nergal” and the Plague in the Levant. Ugarit-Forschungen 48: 223-48.

[7] Lorentzen, H.F, T. Benfield, S. Stisen and C. Rahbek. 2020. “COVID-19 is Possibly a Consequence of the Anthropogenic Biodiversity Crisis and Climate Changes” Danish Medical Journal 67(5): A205025.

0 notes

Text

Fashion’s biodiversity problem

Nature is declining at unexampled rates, scientists complete this year. though it’s the results of several tributary and sophisticated factors, fashion may well be one amongst the foremost unmarked.

A huge share of the article of clothing starts out on a farm or during a forest. Its production has caused not simply associate degree transaction in carbon emissions, a tributary to temperature change, however conjointly a decline in diversity — the opposite environmental crisis facing the earth and therefore the focus of associate degree horrifying report the world organization issued earlier this year.

"If no action is taken, fashion brands can notice themselves probably squeezed between falling average per-item costs, deeper discount levels, rising prices and resource deficiency on the worth chain,” the world Fashion Agenda and therefore the state capital Consulting cluster wrote during a joint 2017 report evaluating the industry’s impacts on the surroundings, as well as diversity.

Leather associate degreed viscose — that is commonly touted as an eco-friendly fiber — square measure among the foremost damaging materials, a tributary to deforestation in precious ecosystems as well as the Amazon. regarding eighty percent of land-based diversity depends on forests, and once a forest is cleared, gone with it square measure the plants and animals that known as it home. Cotton, too, has broken natural habitats by exchange native vegetation, whereas intensive use of pesticides has caused insect populations and diversity within the soil to plummet. Wool and cashmere square measure likewise driving environs loss and soil degradation at a dangerous speed.

An imperative crisis

Impacts vary by class, however out and away the largest is environs loss, that is pushing species “to the brink of extinction”, says Nicole Rycroft, founder and decision-maker folks environmental organization cover. Across the earth, populations of vertebrate animals have plummeted by regarding sixty percent since 1970 — and fewer than twenty percent of the world’s ancient forests stay massive enough to take care of the biological diversity that’s there.

In 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature highlighted associate degree “urgent need” for the attire sector to require action on its role in diversity loss. The trade didn’t quite jump into gear, however, this year diversity did feature collectively of the 3 main pillars within the Fashion treaty, the set of property objectives free at the G7 Summit in August with signatories as well as Zara parent company Inditex, H&M Group, Kering, and Chanel.

The first step brands take as a part of their diversity commitment is to live their impacts on key species and ecosystems.

The results may be stunning. Kering, for instance, learned once it compiled its Environmental Profit & Loss statement that albeit its brands don’t get greatly cashmere relative to different materials, it had associate degree outsize environmental impact and was degrading ecosystems. (It has since modified its sourcing strategy — a lot of from Kering in our next installment.)

Stella songwriter reportedly off a procurement of viscose once learning the provider didn’t adhere to the standards of not sourcing from ancient or vulnerable forests.

© Frank Philip Stella songwriter

Cotton is that the commonest natural material utilized in an article of clothing, creating up a 3rd of all textile fibers. It uses 2.4 percent of the world’s cropland, however a full sixteen percent of the world’s pesticides, in step with chemical Action Network. “When you spray everything chemically, you destroy all the life,” says Helen of Troy Crowley, World Health Organization heads property sourcing at Kering. (She is presently on sabbatical and serving briefly as senior authority for resilient provide chains at Conservation International.)

The impacts of this intensive agriculture aren't distinctive to fashion — abundant of the world’s food is fully grown during a similar manner, with similar impacts. whereas elements of the food trade have begun to shift practices in response to public pressure, it’s not quick enough for conservationists, World Health Organization would love to envision forceful changes across the board, as well as on farms that offer fast-fashion brands, luxury homes, and everything middle.

“The undeniable fact that there's diversity — or accustomed be diversity, even worse — on farms is admittedly invisible,” says Julie Stein, decision-maker of life Friendly Enterprise Network. particularly on farms that square measure a part of international provide chains and grow only 1 crop on an outsized scale — a system referred to as monoculture — the life is already gone. “And then our cultural memory that there accustomed be life on farms is additionally gone, and it becomes the new tradition that life isn’t a part of that equation.”

Evolved farming practices will facilitate

Because of what quantity of the world’s land is employed for farming, this has profound impacts — however, there's the conjointly profound chance. life typically lives in protected areas, however, it doesn’t, and can’t, exist there completely. “Agricultural lands square measure Alaska for life,” says Stein. “Species ought to be ready to move out of their very little protected island at some purpose, particularly with temperature change and every one the threats that bring to life. they'll need to migrate for mates, for food, for shelter.”

Her organization works with farmers to form their lands accommodating for life — with selected stress on massive predators due to their importance not solely within the organic phenomenon, however within the ripple effects that chain has on things like water quality and carbon storage in soil. “If you don’t have apex carnivores within the system, everything from the highest down is affected, all the way down to the microbes within the soil,” she says.

Less than twenty percent of the world’s ancient forests stay massive enough to take care of the biological diversity that’s there.

© Canopy

The soil has return below its own spotlight. It’s one amongst the foremost biodiverse ecosystems on the earth — with microscopic life most of the people can ne'er see, nonetheless is directly connected with the range of life on top of the ground. however it’s below threat: scientists have the same if current practices persist, the world’s soil will solely support another sixty crop harvests. “We’ve simply been pounding the soil. But soil, it’s just like the skin on our earth. It’s an animate thing,” says Crowley.

Unsustainable agriculture and deforestation square measure culprits, however, therefore, is overgrazing by animals. A majority of Mongolia’s grasslands, for instance, are degraded and square measure slowly turning into a desert. Overgrazing of eutherian — cashmere goats particularly — is answerable for quite three-quarters of the decline, that is elaborately connected with wearing away.

But it’s not on the subject of grass and soil: those changes threaten the vary of life that inhabit the realm, several of them already rare or vulnerable, as well as snow leopards, ibex, golden eagles, and boreal owls. Elsewhere, overgrazing for wool and different fibers will shift the vegetation balance — increasing grass-like plants and decreasing woody shrubs and trees, whereas conjointly eating away soil.

Plant-based fibers will have negative impacts, too

Viscose and different cellulose-based fibers square measure directly driving deforestation within the Amazon, Indonesia, North America et al.. quite a hundred and fifty million trees square measure logged for these fibers annually and use of the material has been ascent quickly, in step with cover. It’s particularly difficult, says Rycroft, as a result of viscose could be a “very inefficient fiber”. It takes up to four.5 heaps of trees to form one ton of viscose. “In a resource-constrained world, I simply don’t assume we will afford that level of unskillfulness.”

A growing range of brands have wanted a lot of property sources of viscose, however, it’s not forever a simple switch. Frank Philip Stella songwriter, a partner of CanopyStyle, off a procurement of viscose once learning the provider didn’t adhere to the standards of not sourcing from ancient or vulnerable forests, in step with Rycroft. (Stella songwriter declined to comment.)

Leather and fur square measure escalating the harm

Leather is one amongst the foremost profitable merchandise of the eutherian trade, which could be a major explanation for deforestation and uses regarding eighty percent of agricultural lands globally. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has the same the eutherian trade is additionally probably the biggest supply of apparel-related pollution, inflicting “dead” zones in coastal areas and degradation of coral reefs, among different environmental and human health issues.

While a little share of sourcing, wild animals killed for his or her skins and furs square measure direct hits to ecosystems. Removing predators like massive cats cannot solely threaten that species, however, shift the relationships between all the animals below it on the organic phenomenon. Trappers conjointly catch unplanned animals, which then has its own unpredictable system impacts.

Then there’s the difficulty of packaging. no matter what garments square measure made from, the packaging they're shipped in is another driver of deforestation, and one thing the trade has to reckon with.

On the entire, there’s been some movement.

LaRhea Pepper, the decision-maker of Textile Exchange, says quite sixty brands that her organization partners with have committed to finding a lot of property solutions for a hundred percent of their cotton by 2025. whereas that’s important, it remains a call the ocean. “It’s regarding about to vital mass, about to a hundred percent of brands having totally accountable solutions across the board.”

0 notes

Text

Tropical forests quite resilient to warming

In an ambitious, long-term study of more than half a million trees, a virtual army of scientists has found that tropical forests are more resilient to warming temperatures than most climate models predict – but only up to a point.

Once temperatures pass a 32-degree-Celsius threshold, the forests – a major carbon reservoir – become four times more sensitive to the heat, causing them to release carbon dioxide more rapidly.

“Tropical forests store vast amounts of carbon in their trees,” says lead author Martin Sullivan from the University of Leeds, UK.

“If all this would be released at once it would be equivalent to around 25 years’ worth of global fossil fuel emissions.”

What triggers this is therefore a major concern, yet understanding how sensitive tropical forests are to rising temperatures is one of the greatest sources of uncertainty in climate modelling, the researchers write in the journal Science.

Forests release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when the amount of carbon gained by tree growth is less than that lost through death or decay through environmental impacts.

Measuring giant Ceiba in the Choco rainforest, Colombia. Credit: Pauline Kindler

The fact that trees are long-lived has been a key obstacle to measuring how they respond and adapt to global warming over time, so all models until now have been limited by short-term insights.

The team of 225 researchers from across the globe took a different approach.

First, they measured the diameter and height of trees from 590 permanent tropical forest plots in South America, Africa, Asia and Australia and identified nearly 10,000 species. Each tree was tagged so they could track their rate of growth and death over the years.

This enabled the team to calculate the rate at which forests take carbon from the atmosphere and how long they retain it, factoring in the different climates.

“By relating the amount of carbon forests store to the climate the trees grow in we could see how climate controls forest carbon stocks,” Sullivan explains.

“Comparing forests in different locations allows us to observe how forests grow in a particular climate after having had time to adapt.”

The researchers then looked at another 223 forest plots to confirm the relationships they observed.

They found that while trees adapted well to minimum night-time temperatures, maximum daytime temperatures had the biggest impact on carbon storage, mainly by reducing their growth rate, followed by tree mortality from droughts.

Daytime temperatures below 32 degrees had little effect, suggesting forests are less sensitive than most models predict, in part because their high biodiversity enables more tolerant trees to replace less well-adapted species.

The biggest impacts were predicted in South America, with the highest warming, which would drive more than two thirds of the biome over the threshold.

While carbon dioxide fertilisation could, to some degree, mitigate the impact, this would be thwarted by rapid temperature increases, habitat fragmentation, logging and fires, which increase the trees’ vulnerability.

“Our results indicate that forests are surprisingly resilient to small increases in temperature, but this resilience is only up to a point,” says Sullivan.

“To ensure this resilience, we need to protect and connect forests so tree species can move to new locations, as differences in species composition between different forests is likely to be key to their ability to adapt.”

Meanwhile, the researchers say, it is critical to limit emissions and stabilise the Earth’s climate.

Already, a quarter of tropical forests are facing temperatures over the 32-degree threshold, and even the 1.5- or two-degree targets would push the majority of trees over the edge and trigger excess release of carbon into the atmosphere, causing spiralling feedback loops.

But the coronavirus lockdown offers a unique opportunity to take action.

“By not simply returning to ‘business as usual’ after the current crisis we can ensure tropical forests remain huge stores of carbon,” says co-author Oliver Phillips.

“Protecting them from climate change, deforestation and wildlife exploitation needs to be front and centre of our global push for biosecurity.”

The post Tropical forests quite resilient to warming appeared first on Cosmos Magazine.

Tropical forests quite resilient to warming published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

Unite Behind Science!

Originally posted on LinkedIn

As I write this, the world holds its breath. The global COVID 19 pandemic, the coronavirus, affects many infected and worried people around the globe. Countless doctors, nurses and medical workers are tirelessly helping on the ground. Governments are on highest alert to control the situation, talking advice from scientific experts who are learning on the fly. Healthcare companies like Bayer are also in constant contact with authorities worldwide and provide support wherever possible.

It is way too early to learn lessons from this global pandemic. We are still in the middle of it. But I believe there is a bigger question that is being touched on here where I would urge us to develop a common understanding. I’m referring to a disturbing development in recent years that has weakened trust in science and in the role of experts in general.

In the context of coronavirus, just a few days ago, the��New York Times put it this way:

"The failures to contain the outbreak and to understand the scale and scope of its threat stem from an underinvestment in and an under-appreciation of basic science."

This week, despite the focus on fighting a global pandemic, UN Secretary General Guterres still commented on the WMO global report on Climate 2019 because of how relevant the findings are. The Fridays for Future movement received a lot of applause for its ability to put climate change higher on the global agenda. I believe it is even more remarkable how the movement’s core argument has been grounded in science.

For many years, scientific denialism has slowed down action. Today, scientific consensus exists in cause and effect of climate change. Just last year, similar scientific backing was established for biodiversity loss.

Bayer is a leading company in health and agriculture grounded in scientific findings. In Crop Science, we have one of the highest investments in research and development of any corporation ever.

Overall, our EUR 5.3 billion annual R&D investment puts us in the top five of all German companies and well in the top 25 globally.

Bayer employs more than 18,000 researchers and engages in some 8,000 scientific partnerships with third parties every year. We can only fulfill our purpose of "Science for a Better Life" by being a welcomed partner in the scientific community.

Given the huge global challenges in public health, food systems, and an economy that has long exceeded planetary boundaries, only relentless focus on innovation can help humanity to find and implement the solutions that will provide a path forward. In 2018, the leading 50 corporations in the world invested more than EUR 310 billion for R&D.

Against this backdrop, it is striking to me that the R&D budgets of major global companies have only played a minor role in the sustainability debate which seems rather revolving around the emissions of today than the breakthroughs of tomorrow. To change that, we will ask our upcoming sustainability council to scrutinize our future pipelines with a view to putting even more emphasis on sustainability.

Distrust in science - How did it come to this? The big dilemma is that while innovation and scientific progress is urgently needed, trust in science is more and more dwindling. I see three main trends contributing to this disturbing development:

First, we live in times where people trust their laymen peers rather than experts and new communication technology stimulates sharing of false information far more than sharing of scientifically proven facts. A scary example for this is the growing skepticism towards vaccination.

My hope is that COVID-19 will reverse this trend. Football manager Jürgen Klopp made a point recently when refusing to comment on coronavirus, saying: “People with knowledge should talk about it.”

Against this backdrop, it is great to see how undisputable experts in their fields regain the ear of the public, such as Chen Wei, the 54-year-old Chinese virologist who is building on the knowledge and skills she gained fighting Sars and Ebola, Christian Drosten, the director of the Institute for Virology at Berlin's Charite hospital or National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Anthony S. Fauci in the United States, another veteran of the Ebola crisis.

Second, industry needs to confront its well-documented history of systematically undermining scientific findings in order to postpone the usually unpleasant rendezvous with truth. Many sectors like tobacco, chemicals, food and oil have invested significant resources into putting their short-term revenue above long-term science-led ones. For denial, sectors and individual corporations paid a price. The highest cost, however, derived from undermining the trust in the very science businesses depend on.

Third, academia falls as well in the trap. Such as when it becomes the mouthpiece of activism and presents findings as the truth even when general scientific consensus or reproducibility is low. It includes deriding all industry-funded findings resulting into the crippling of one of the major sources of funding of scientific discovery.

Out of these trends, different narratives that erode the trust in science have emerged:

The view from the left: Science can’t be trusted because it is industry-funded and, therefore, the results are skewed.

The view from the right: Science can’t be trusted because academia is a left-leaning enterprise deriving biased results from an intellectual monoculture.

The view from either left or right: An overly technology-friendly ideology in the name of science can’t be trusted because collides with a romantic world view or religious beliefs.

Distrust in science - What does it lead to? Regulators around the world are drastically feeling the consequences of the erosion of trust in science. Any regulatory process is inherently political. However, in recent history, in order to partially reduce the influence of important businesses, independent scientific assessment has allowed regulators to better reflect on public health or environmental concerns in their approval processes. The overhaul of the European food safety and chemical regulation at the beginning of this century following the BSE crisis is an example of this process.

In a climate where experts are less and less regarded, regulators are now facing an equally strong pressure. Both industry and activists need to come to grips with how unhelpful some current tactics are to society. To share an example where we got it wrong in 2017: Just last week, there was a publication about past activity where originators of studies hid behind a smoke-screen with the belief in doing so more effectively to influence public opinion.

There is a broad societal majority supporting innovation to transform how we produce, consume, and live on this planet. The role of regulators is to decide the extent to which business can turn innovation into products that create value. Everyone should have an interest to strengthen science in the context of this process.

For Bayer, this has a five immediate consequences:

Starting this year in Germany, where a huge part of our research activity originates, we will roll out a global collaboration register that will create transparency around Bayer’s scientific partnerships.

In future dossiers for regulators, we will include all studies we have commissioned including those who have adverse findings.

We will continue to promote a high level of transparency and publish regulatory dossiers and scientific findings.

Scientific progress also stems from dissenting voices and we will engage in greater dialogue to learn from scientists who have contrarian viewpoints.

We will seek to build alliances with other corporations to drive global standards for science engagement and speak up where we believe industry is undermining science on the lookout for short-term gains.

We need a societal push for innovation that helps address the biggest challenges of our time. Let’s overcome the growing societal apprehension regarding academia and industry collaboration in the scientific field. The world will only stand a chance to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations if trust in science is restored.

A new societal contract is needed, which states that industry must accept inconvenient truths about the limitations of its freedom to operate, with increased consciousness regarding the undeniable planetary boundaries. Conversely, other societal stakeholders need to trust in science-based risk assessments that enable innovation.

source: https://www.csrwire.com/press_releases/44295-Unite-Behind-Science-?tracking_source=rss

0 notes

Text

En route to human extinction

A new mass extinction is approaching, and this time, humans might be the one to blame.

When life began on Earth 3.5 billion years ago, humans were out of sight—we have only existed in the last 13 million years. Hence, if life on Earth was compressed into a day, humans have only existed in its very last second. Yet in this seemingly short period of time, the magnitude of destruction caused by humans has been incalculable and irreversible, which now begs the question: will the next extinction be from our own doing?

University of Chicago paleontologists David Raup and J. John Sepkoski, who both contributed in the field of extinction events, conducted a study in 1982 on mass extinctions of marine fossils and stated there has already been five mass extinctions the Earth has experienced. Each of the mass extinctions—commonly called the “Big Five,” coined by American paleobiologist John Alroy—occurred during Ordovician, Devonian, Permian, Triassic, and Cretaceous periods respectively; but all of which were caused by natural disasters.

The sixth mass extinction, called the Holocene extinction, is not caused by nature unlike the Big Five that came before it. As it turns out, the sixth mass extinction only has humans to blame.

In too deep

In an event of mass extinction, the Earth’s biodiversity decreases quickly and extensively. However, extinction is a natural part of evolution, as Mother Nature Network Science Editor Russell McLendon wrote in 2017, adding that scientists also say an estimated 99 percent of all species in the history of the planet have all faced their own extinctions already. Despite it being a natural occurrence, McLendon said it is alarming when too many species die out too quickly at such a short amount of time. In fact, a 2017 Stanford Universitystudy revealed that as much as 50 percent of the species that have lived with humans are already gone. As a result, this rapid and widespread extinction will cause an inevitable disruption of ecosystems.

Currently, humans are relatively far from extinction, especially with a growing population that’s closing in at eight billion, as per latest statistics. With everything else going extinct, our own demise is not too far from reality.

Self-inflicted extinction

A 2015 study concluded that due to the alarmingly high, and still growing, extinction rate, a mass extinction is definitely imminent. Human destruction of other organisms at an accelerating rate initiates “a mass extinction episode unparalleled for 65 million years,” the study reads.

In addition, according to a paper in The Anthropocene Review, the kind of extinction humans are currently facing is unprecedented in Earth’s history due to four reasons.

Firstly is the “global homogenisation of flora and fauna,” a crisis on biodiversity that explains the decrease of planet’s plants and animals. Second, humans have taken over 25 to 40% of the planet’s net primary production for its own use. Third, humans have intervened with and orchestrated the evolution of other species by genetically engineering animals and plants to satisfy a certain want. Lastly, humans have drastically linked the biosphere with the technology by being highly dependent on technological networks and artefacts.

These imply that through the domination of humans, Earth has transformed into a playground for humans to do as they please, including destruction. Humans have been able to cultivate different species in locations that are not in their native environment, intervene with its production through man-made and unnatural means, and consume all of it with complete disregard of all of the other species.

Symptoms of an impending mass extinction also include climate change, overpopulation, income inequality, land degradation, and overexploitation of animal species; all of which are happening as of the moment.

If the rate of extinction continues, the earth’s biodiversity will be depleted enough that humans will not reap its benefits in as soon as three human lifetimes. For humans however, this depletion could be considered as a permanent loss as it would take earth millions of years to diversify.

Reversing self-destruction

Despite this, it is worth noting that although humans are the problem, they are also the solution. Majority of studies claim that humans only have about three lifetimes left to save the earth. However, these studies also claim that if humans want to save the planet and its own specie, now is the time to act. Avoiding the sixth mass extinction requires immediate and huge conservation efforts to save species that are at risk due to loss of habitat, overexploitation for economic gain, and climate change, all of which are caused by human activity.

All of the reasons for the incoming mass extinction are all due to the notion that earth’s limited resources can accommodate humans’ insatiable needs. Unfortunately, with the rate that humans are going with abusing the planet, a new day just might never come, unless humans collectively decide to save the Earth.

This article was originally published in The Benildean This article won an Award of Excellence under the Communication Skills category of the 7th Philippine Student Quill Awards This article was nominated for the Top Award under the Communication Skills category of the 7th Philippine Student Quill Awards

0 notes

Text

Assignment代写:Harm of ocean acidification

下面为大家整理一篇优秀的assignment代写范文- Harm of ocean acidification,供大家参考学习,这篇论文讨论了海洋酸化的危害。海洋酸化,指的是由于海洋吸收大气中过量的二氧化碳,使海水逐渐变酸。目前海洋每年吸收的二氧化碳都在80亿吨左右,虽然对于减缓气候变暖起到了重要的作用,但海洋也为此付出了高昂的代价。有结果表明,海洋酸化在古代生物灭绝中起到了极大的作用。如果海洋酸化的问题再不解决,我们可以预见到它对某些海洋生物的影响,其中贝类动物面临的风险最大。

More than 250 million years ago, the earth experienced one of the most dramatic extinction crises, with about 90 percent of Marine life and 70 percent of terrestrial life disappearing. Exactly what caused so many species to die off has long been a matter of debate.

Now, a new study offers important clues. Scientists believe that ocean acidification, caused by rising levels of carbon dioxide in the air, may have played a crucial role in the ancient extinction event. Marine life with calcium carbonate shells, in particular, is particularly vulnerable to acid conditions.

Ocean acidification refers to the gradual acidification of seawater as the ocean absorbs excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The term "ocean acidification" first appeared in the famous British scientific journal nature in 2003. The oceans currently absorb about 8 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year, and while it has played an important role in slowing warming, the oceans have also paid a high price.

As atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide rise over the next few decades, and the seawater that absorbs the gas eventually becomes more acidic, the earth is likely to head toward another serious extinction event that could repeat the history of more than 250 million years ago.

Canada ocean physicist alvaro monte Montenegro said: "although compared with many other what is happening, the role of acidification of the oceans, in fact, it is difficult to quantify, but our results clearly show that ocean acidification in the ancient extinction events plays a major role, played a great role."

It is clear that humans have made and will continue to make the oceans more acidic, and we can expect it to affect some Marine life, of which clams, mussels and other aquatic shellfish are most at risk. The results suggest that life may not be able to adapt quickly enough to change the ocean's pH.

PH is a measure of the activity of hydrogen ions in a solution, which is generally a measure of the pH of the solution. The higher the pH goes to zero, the more acidic the solution. And the more we go to 14, the more alkaline the solution is. At room temperature, a solution with a pH of 7 is neutral.

The evolution of life is interspersed with many major extinction events, including the one that wiped out most dinosaurs about 65 million years ago. The sequence of the most extreme events so far goes back more than 250 million years. The Permian ~ Triassic extinction event is a mass extinction event that occurred between the Permian and Mesozoic Triassic about 250 million years ago. In terms of lost species, 70% of earth's terrestrial vertebrates and up to 96% of all sea life disappeared. The extinction also caused the only mass extinction of insects, with 57 percent of "families" and 83 percent of "genera" disappearing. It took millions of years for the terrestrial and Marine ecosystems to fully recover, longer than other mass extinctions. PTB is the largest of five mass extinctions in the geological era, so it's informally called a "mass extinction," or "mother of mass extinctions." It took at least 100, 000 years for the ocean to return to normal after an estimated 450 gigatons of dissolved carbon dioxide were blamed for an extinction event 65 million years ago.

Scientists know that giant volcanic eruptions send huge amounts of methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at very high temperatures. Geological studies have shown that oxygen levels in parts of the ocean floor are very low, but it's still not clear what causes it.

In order to solve some of the mystery, alvaro monte Montenegro and his colleagues created a computer model, simulation and extinction in before extinction. The model includes a continent that is precisely aligned according to historical circumstances, and also the first time the ridg-strewn seafloor has emerged to create a lifelike pattern of flow circulation. After setting the temperature and carbon dioxide concentrations to the maximum levels they assumed existed at the time, the researchers looked at what would happen in the ocean. Their results confirm that warmer climates do not account for the record of changes in the oceans at PTB, and that high levels of carbon dioxide alone can cause a significant drop in the ocean's pH.

British geologist helwig Noel Paul said: "as for why the extinction of oxygen at the bottom of the ocean is so little, the model does not provide much evidence, it shows that we need to do a lot of research work, can we truly understand occurred in the biggest extinction event in the history of the earth."

But acidification, or lack of oxygen, is an impending crisis in the modern ocean. The fossil record shows that the aquatic shellfish were destroyed in PTB because the acidic environment made it difficult for them to secrete and feed their shells.

The severity of the problem has been exacerbated by the cold water, which means aquatic shellfish in the higher latitudes face the greatest threat today. According to the researchers' projections, the first casualties could be pteropods between 2030 and 2050. These snails live in surface waters at high latitudes, forming the lowest end of many fish and bird food chains. Between now and 2030, the southern hemisphere's oceans will corrode snails' shells. These mollusks are an important source of salmon in the Pacific, and if their populations decline or disappear in some areas, that could affect the salmon fishing industry. In addition, the loss of coral reefs in the sea's continental shelf, which generate billions of dollars a year for tourism, will be a major setback for tourism.

Today's oceans are more acidic as more carbon dioxide enters the atmosphere through fossil fuels and other sources and is likely to spread southward into warmer waters, threatening creatures such as clams, oysters and corals.

Since the industrial revolution, more than a third of the carbon dioxide released by human activities has been absorbed by the ocean, increasing the concentration of hydrogen ions in surface waters by 30 percent over the past 200 years and lowering pH by 0.1. The increasing acidity of sea water breaks the balance of Marine chemistry and threatens the Marine ecosystem. Many Marine organisms and even ecosystems that depend on the stability of chemical environment are faced with huge threats. The extinction of some shellfish is a strong proof of ocean acidification. Ocean acidification has also severely damaged biodiversity and caused the emergence of some invasive species. As the main force of photosynthesis in the ocean, phytoplankton species are numerous, their physiological structures are diverse, and their ability to use different forms of carbon in the sea water is also different. Ocean acidification will change the conditions of competition among species.

With so much carbon dioxide being absorbed, the oceans are acidifying at an unprecedented rate. At present, the only effective solution to the problem is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

51due留学教育原创版权郑重声明:原创assignment代写范文源自编辑创作,未经官方许可,网站谢绝转载。对于侵权行为,未经同意的情况下,51Due有权追究法律责任。主要业务有assignment代写、essay代写、paper代写服务。

51due为留学生提供最好的assignment代写服务,亲们可以进入主页了解和获取更多assignment代写范文 提供美国作业代写服务,详情可以咨询我们的客服QQ:800020041。

0 notes

Text

Tropical forests quite resilient to warming

In an ambitious, long-term study of more than half a million trees, a virtual army of scientists has found that tropical forests are more resilient to warming temperatures than most climate models predict – but only up to a point.

Once temperatures pass a 32-degree-Celsius threshold, the forests – a major carbon reservoir – become four times more sensitive to the heat, causing them to release carbon dioxide more rapidly.

“Tropical forests store vast amounts of carbon in their trees,” says lead author Martin Sullivan from the University of Leeds, UK.

“If all this would be released at once it would be equivalent to around 25 years’ worth of global fossil fuel emissions.”

What triggers this is therefore a major concern, yet understanding how sensitive tropical forests are to rising temperatures is one of the greatest sources of uncertainty in climate modelling, the researchers write in the journal Science.

Forests release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when the amount of carbon gained by tree growth is less than that lost through death or decay through environmental impacts.

Measuring giant Ceiba in the Choco rainforest, Colombia. Credit: Pauline Kindler

The fact that trees are long-lived has been a key obstacle to measuring how they respond and adapt to global warming over time, so all models until now have been limited by short-term insights.

The team of 225 researchers from across the globe took a different approach.

First, they measured the diameter and height of trees from 590 permanent tropical forest plots in South America, Africa, Asia and Australia and identified nearly 10,000 species. Each tree was tagged so they could track their rate of growth and death over the years.

This enabled the team to calculate the rate at which forests take carbon from the atmosphere and how long they retain it, factoring in the different climates.

“By relating the amount of carbon forests store to the climate the trees grow in we could see how climate controls forest carbon stocks,” Sullivan explains.

“Comparing forests in different locations allows us to observe how forests grow in a particular climate after having had time to adapt.”

The researchers then looked at another 223 forest plots to confirm the relationships they observed.

They found that while trees adapted well to minimum night-time temperatures, maximum daytime temperatures had the biggest impact on carbon storage, mainly by reducing their growth rate, followed by tree mortality from droughts.

Daytime temperatures below 32 degrees had little effect, suggesting forests are less sensitive than most models predict, in part because their high biodiversity enables more tolerant trees to replace less well-adapted species.

The biggest impacts were predicted in South America, with the highest warming, which would drive more than two thirds of the biome over the threshold.

While carbon dioxide fertilisation could, to some degree, mitigate the impact, this would be thwarted by rapid temperature increases, habitat fragmentation, logging and fires, which increase the trees’ vulnerability.

“Our results indicate that forests are surprisingly resilient to small increases in temperature, but this resilience is only up to a point,” says Sullivan.

“To ensure this resilience, we need to protect and connect forests so tree species can move to new locations, as differences in species composition between different forests is likely to be key to their ability to adapt.”

Meanwhile, the researchers say, it is critical to limit emissions and stabilise the Earth’s climate.

Already, a quarter of tropical forests are facing temperatures over the 32-degree threshold, and even the 1.5- or two-degree targets would push the majority of trees over the edge and trigger excess release of carbon into the atmosphere, causing spiralling feedback loops.

But the coronavirus lockdown offers a unique opportunity to take action.

“By not simply returning to ‘business as usual’ after the current crisis we can ensure tropical forests remain huge stores of carbon,” says co-author Oliver Phillips.

“Protecting them from climate change, deforestation and wildlife exploitation needs to be front and centre of our global push for biosecurity.”

The post Tropical forests quite resilient to warming appeared first on Cosmos Magazine.

Tropical forests quite resilient to warming published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes