#Wylie Philips 1931

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

THE UNSUNG LITERARY BASIS BEHIND UNIVERSAL'S "THE INVISIBLE MAN" (1933).

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on First Edition hardcover dust jacket cover art to "THE MURDERER INVISIBLE," written by Philip Wylie and published by Farrar & Rinehart Incorporated in 1931, New York, USA.

MINI-OVERVIEW: Mystery and science fiction novel of a man who can turn himself invisible and seeks to rule the world. Wylie freely admits indebtedness to Wells' novel "The Invisible Man" (which Wylie, unaccredited, helped write the screenplay for the 1933 Universal horror film).

EXTRA INFO: [Reference: Clareson, Science Fiction in America, 1870s-1930s 835. In 333. Bleiler (1978), p. 213. Reginald 15693. Hubin (1994) p. 882].

Sources: www.abebooks.com/first-edition/MURDERER-INVISIBLE-Wylie-Philip-Farrar-Rinehart/30864323096/bd.

#Wylie Philips 1931#Classic Monsters#1931#Classic Movies#30s Cinema#First Edition Books#Hardcover Books#The Murderer Invisible#The Murderer Invisible 1931#Halloween Vibes#Books#Spooky Season#Spooky Art#Halloween Art#Invisible#Halloween Season#Universal horror#Universal Monsters#The Invisible Man 1933#Dust Jacket#Thirties#Vintage Books#Dust Jacket Illustration#Halloween Mood#Philip Wylie#Illustration#Cinema#United States#Hardcover#1930s

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sci-Fi Saturday: The Invisible Man

Week 12:

Film(s): The Invisible Man (Dir. James Whale, 1933, USA)

Viewing Format: DVD

Date Watched: August 13, 2021

Rationale for Inclusion:

After a diversion into aeronautic sci-fi and a post-apocalyptic narrative, our survey returns for one last example of a Pre-Code horror hybrid: The Invisible Man (Dir. James Whale, 1933, USA).

As with Island of Lost Souls (Dir. Erle C. Kenton, 1932, USA), The Invisible Man is based on an H.G. Wells novel. Unlike when Paramount Pictures bought the rights to adapt The Island of Dr. Moreau, however, Wells demanded script approval as part of the deal with Universal Studios for them to adapt The Invisible Man. Wells had hated the adaptation of The Island of Dr. Moreau, finding its emphasis on horror and lack of imagination miserable, and was not going to let a similar fate befall another one of his novels.

Although the rights were secured by Universal not long after the success of Dracula in 1931, it would take two years for the studio to assemble a satisfactory crew, script and cast. James Whale signed onto the project in 1931, but after the huge success of Frankenstein (1931, USA) left the project, not wanting to be associated as a horror director. However, after his return to romance with The Impatient Maiden (1932, USA) failed at the boxoffice, Whale returned to horror, first with The Old Dark House (1932, USA), which reunited him with Boris Karloff, and then signing back on to The Invisible Man. During Whale's absence from the project many screenwriters and drafts of screenplays, some of which used elements from another novel that Universal bought the rights to, The Murderer Invisible by Philip Wylie, had come and gone and failed to meet with Wells' approval.

In June of 1933, a script that finally met with Wells' approval was produced by R. C. Sherriff, who had written the play Journey's End, which sent Whale's star on the rise. This screenplay originated the idea that the experimental monocane serum that Dr. Jack Griffin (Claude Rains) produces not only makes him invisible, but slowly destroys his sanity. Similar to the lab setup and lightning power in Whale's Frankenstein, insanity as a byproduct of the invisibility would inform later adaptations of the Wells novel, including the early 2000s television series, which also featured a clip from the 1933 film in its opening credits sequence.

Reactions:

As resistant as Whale initially was to making horror films after Frankenstein, he proved with each subsequent one that he made how good he was at it. With the help of a group of repertory creatives both on and off screen, Whale put a pathos and humor into his horror films in a way that no other director working in the genre in the 1930s did. It's why over 90 years later Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Invisible Man, and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935, USA) are some of the best horror films of their era and amongst the most influential of all time.

Yet, the horror genre aspects in The Invisible Man are not as prominent as its science fiction categorization. Griffin is a mad scientist, that is an otherwise average person, whose hubris and curiosity makes a monster out of him. My partner noted that he considers The Invisible Man to definitely be a monster movie, but more of a suspense or mystery film than a horror film. Any movie that features a serial killer is at least partially horror in my reckoning, but the way the narrative of The Invisible Man unfolds, it is closer to a suspense film like M (Dir. Fritz Lang, 1931, Germany) than an unquestioned horror film with a fantasy monster like Dracula (Dir. Tod Browning, 1931), despite all three having narratives that boil down to "what is the mystery surrounding this man" then "this man is a monster and must be destroyed for the greater good."

The mystery and monstrosity around Griffin is rendered possible through the performance of Claude Rains and some inventive special effects. As with Whale's casting of Karloff in Frankenstein, his role as the title character in The Invisible Man was a star-making role for theater actor Rains. Having to rely on his voice and physicality, but not his face, gave Rains some trouble during production, but he ultimately created a character that oscillates between aloofly mysterious and a madcap lunatic.

A combination of post-production optical work, clever blocking, and use of wires rendered Griffin invisible. The special effects used would remain the standard way of conveying an invisible entity prior to computer generated imagery and post-production work becoming dominant in the industry. As silly as it may feel knowing that Griffin unwraps his head revealing nothing beneath is achieved by something as simple as Rains wearing his shirt and jacket above his head as he removes the bandages it remains visually iconic.

My only issue with the practical special effects comes at the film's climax when Griffin exits the cabin where he is hiding out and he leaves shoe prints in the snow, despite it being previously established that to be fully invisible (as he is in the scene) he must be totally naked. What baffles me if the use of shoe prints instead of footprints was a question of deliberate censorship or thoughtless oversight. I usually don't get nitpicky about these types of goofs in movies, but it stands out sharply in an otherwise carefully engineered film.

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Island of Lost Souls

1930s American film horror, especially that from Universal Studios, for the most part has this reputation of being almost kid friendly, with its focus on monsters and more fantastical matters, along with a lack of visceral gore or other factors. However, that was mainly on account of the Hay’s Code, the major censorship scheme that was first instituted in 1930, but properly began being enforced in 1934. In that gap of time, there were quite a few horrors, made by the big studios no less, that definitely were pushing the envelope. Sometime on here I probably will have a talk about the infamous 1932 Freaks, but today, starting off a little linked week of articles, I’m going to talk about a Paramount Studios production, 1931′s Island of Lost Souls, the first official film version of H.G. Wells’ novel The Island of Dr. Moreau. (Apparently there is a very obscure, long thought lost German film from about a decade earlier which borrowed liberally from the book).

Now this starts an ongoing theme of adaptations of Wells’ writings; namely that it makes some changes that Wells really didn’t approve of. Specifically, the novel was another one of those cases of Wells getting on his soapbox about his utopian ideals. Man, he was a major mover and shaker in the world of SF- sorry, “Scientific Romances”, but boy I hate to think what he’d have come out with if Twitter had existed back then. This film version instead focuses very firmly on the horror aspect, and in fact draws out one element of the narrative only vaguely touched upon in the book. Namely, there is a strong element of bestiality running through this. In this version, Moreau (played wonderfully by Charles Laughton, giving us a very haughty and superior character) wants to see if mating between his raised to humanoid form animals and actual humans is possible. A lot of screen time is given to leads Richard Arlen and Kathleen Burke (credited just as The Panther Woman), and a “will they, won’t they” element. Later, the “good” female lead Leila Hyams is essentially threatened with rape from the beast-men too. This is powerful stuff, which gets more disturbing, when you consider that this is more than likely a full on metaphor for miscegenation, given the time. Yeah, the whole “anywhere foreign is deeply scary and full of weird looking not-really-people” element has dated this one rather badly (in fact, it’s often been thought that this film coined the saying “the natives are restless tonight”).

As icky as the whole sexual/racial elements are today, that wasn’t was what got this one into trouble back in the day (disappointingly). What really got the censors bothered was the element of vivisection. We only get a few brief scenes in Moreau’s “House of Pain”, but they are vividly done, and some of the make-ups on the beast men tell a vivid story of what was done to them. On top of that, there is a very strong theme of Moreau literally playing God in the film, including giving the Law to the people he has created in his image from on high. (I’d have thought that a criticism of religion like this would have really endured the film to Wells tbh.) This is why the BBFC, who have had a very odd relationship with the horror genre for many years, banned it three times, only giving it a certificate after being heavily cut in 1958. It’s actually now available on blu ray over here, fully uncut as a PG. I do think that’s a bit generous though, as again, thematically this is pretty damn dark.

So it’s a film I have a tricky relationship with. As I mentioned, when you notice a lot of the sexual and racial angles at work, it’s a very awkward watch. However, there is a lot of fascinating stuff in here. Honestly, just as a showcase of make-up effects from the time it’s worth a watch, some of the beast men look fantastic. There’s some fun stuff with Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law, including him repeatedly saying one line memorably re-claimed by DEVO. And of course, Charles Laughton is one of the all time great screen mad scientists. So, definitely a mixed bag, it has a lot of good elements, but it has aged less than gracefully. Still, it’s an important title to look at in terms of the history of horror and SF.

Here’s a fun fact to end with. I briefly mentioned Universal Horrors at the start; the director of this one, Erle C. Kenton (who did a very good job here), later did three of the later Universals. His were The Ghost of Frankenstein, House of Frankenstein, and House of Dracula. I’ll say right now that those were far from the best of the series, but they did have pretty energetic direction, for the B-Movies that they were.

#Island of Lost Souls#Pre-Code#Hays Code#Charles Laughton#Erle C. Kenton#Paramount Studios#1931#1930s Movies#H.G. Wells#The Island of Dr. Moreau#Richard Arlen#Leila Hyams#Béla Lugosi#Kathleen Burke#Panther Woman#Philip Wylie

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Evans Brown (July 28, 1891 – July 6, 1973) was an American actor and comedian, remembered for his amiable screen persona, comic timing, and enormous elastic-mouth smile. He was one of the most popular American comedians in the 1930s and 1940s, with films like A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935), Earthworm Tractors (1936), and Alibi Ike (1935). In his later career Brown starred in Some Like It Hot (1959), as Osgood Fielding III, in which he utters the film's famous punchline "Well, nobody's perfect."

Brown was born on July 28, 1891, in Holgate, Ohio, near Toledo, into a large family of Welsh descent. He spent most of his childhood in Toledo. In 1902, at the age of ten, he joined a troupe of circus tumblers known as the Five Marvelous Ashtons, who toured the country on both the circus and vaudeville circuits. Later he became a professional baseball player. Despite his skill, he declined an opportunity to sign with the New York Yankees to pursue his career as an entertainer. After three seasons he returned to the circus, then went into vaudeville and finally starred on Broadway. He gradually added comedy to his act, and transformed himself into a comedian. He moved to Broadway in the 1920s, first appearing in the musical comedy Jim Jam Jems.

In late 1928, Brown began making films, starting the next year with Warner Brothers. He quickly became a favorite with child audiences, and shot to stardom after appearing in the first all-color all-talking musical comedy On with the Show (1929). He starred in a number of lavish Technicolor musical comedies, including Sally (1929), Hold Everything (1930), Song of the West (1930), and Going Wild (1930). By 1931, Brown had become such a star that his name was billed above the title in the films in which he appeared.

He appeared in Fireman, Save My Child (1932), a comedy in which he played a member of the St. Louis Cardinals, and in Elmer, the Great (1933) with Patricia Ellis and Claire Dodd and Alibi Ike (1935) with Olivia de Havilland, in both of which he portrayed ballplayers with the Chicago Cubs.

In 1933 he starred in Son of a Sailor with Jean Muir and Thelma Todd. In 1934, Brown starred in A Very Honorable Guy with Alice White and Robert Barrat, in The Circus Clown again with Patricia Ellis and with Dorothy Burgess, and with Maxine Doyle in Six-Day Bike Rider.

Brown was one of the few vaudeville comedians to appear in a Shakespeare film; he played Francis Flute in the Max Reinhardt/William Dieterle film version of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935) and was highly praised for his performance. He starred in Polo Joe (1936) with Carol Hughes and Richard "Skeets" Gallagher, and in Sons o' Guns. In 1933 and 1936, he became one of the top 10 earners in films.

He left Warner Brothers to work for producer David L. Loew, starring in When's Your Birthday? (1937). In 1938, he starred in The Gladiator, a loose adaptation of Philip Gordon Wylie's 1930 novel Gladiator that influenced the creation of Superman. He gradually switched to making "B" pictures.

In 1939, Brown testified before the House Immigration Committee in support of a bill that would allow 20,000 German-Jewish refugee children into the U.S. He later adopted two refugee children.

At age 50 when the U.S. entered World War II, Brown was too old to enlist. Both of his biological sons served in the military during the war. In 1942, Captain Don E. Brown, was killed when his Douglas A-20 Havoc crashed near Palm Springs, California.

Even before the USO was organized, Brown spent a great deal of time traveling, at his own expense, to entertain troops in the South Pacific, including Guadalcanal, New Zealand and Australia, as well as the Caribbean and Alaska. He was the first to tour in this way and before Bob Hope made similar journeys. Brown also spent many nights working and meeting servicemen at the Hollywood Canteen. He wrote of his experiences entertaining the troops in his book Your Kids and Mine. On his return to the U.S., Brown brought sacks of letters, making sure they were delivered by the Post Office. He gave shows in all weather conditions, many in hospitals, sometimes doing his entire show for a single dying soldier. He signed autographs for everyone. For his services to morale, Brown became one of only two civilians to be awarded the Bronze Star during World War II.

His concern for the troops continued into the Korean War, as evidenced by a newsreel featuring his appeal for blood donations to aid the U.S. and UN troops there that was featured in the season 4 episode of M*A*S*H titled "Deluge".[5]

In 1948, he was awarded a Special Tony Award for his work in the touring company of Harvey.[1][6]

He had a cameo appearance in Around the World in 80 Days (1956), as the Fort Kearney stationmaster talking to Fogg (David Niven) and his entourage in a small town in Nebraska. In the similarly epic film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), he had a cameo as a union official giving a speech at a construction site in the climactic scene. On television, he was the mystery guest on What's My Line? during the episode on January 11, 1953.

His best known postwar role was that of aging millionaire Osgood Fielding III in Billy Wilder's 1959 comedy Some Like It Hot. Fielding falls for Daphne (Jerry), played by Jack Lemmon in drag; at the end of the film, Lemmon takes off his wig and reveals to Brown that he is a man, to which Brown responds "Well, nobody's perfect", one of the more celebrated punchlines in film.

Another of his notable postwar roles was that of Cap'n Andy Hawks in MGM's 1951 remake of Show Boat, a role that he reprised onstage in the 1961 New York City Center revival of the musical and on tour. Brown performed several dance routines in the film, and famed choreographer Gower Champion appeared along with first wife Marge. Brown's final film appearance was in The Comedy of Terrors (1964).

Brown was a sports enthusiast, both in film and personally. Some of his best films were the "baseball trilogy" which consisted of Fireman, Save My Child (1932), Elmer, the Great (1933) and Alibi Ike (1935). He was a television and radio broadcaster for the New York Yankees in 1953. His son Joe L. Brown became the general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates for more than 20 years. Brown spent Ty Cobb's last days with him, discussing his life.

Brown's sports enthusiasm also led to him becoming the first president of PONY Baseball and Softball (at the time named Pony League) when the organization was incorporated in 1953. He continued in the post until late 1964, when he retired. Later he traveled additional thousands of miles telling the story of PONY League, hoping to interest adults in organizing baseball programs for young people. He was a fan of thoroughbred horse racing, a regular at the racetracks in Del Mar and Santa Anita.

Brown was caricatured in the Disney cartoons Mickey's Gala Premiere (1933), Mother Goose Goes Hollywood (1938), and The Autograph Hound (1939); all contain a scene in which he is seen laughing so loud that his mouth opens extremely wide. According to the official biography Daws Butler: Characters Actor, Daws Butler used Joe E. Brown as inspiration for the voices of two Hanna-Barbera cartoon characters: Lippy the Lion (1962) and Peter Potamus (1963–1966).

He also starred in his own comic strip in the British comic Film Fun between 1933 and 1953

Brown married Kathryn Francis McGraw in 1915. The marriage lasted until his death in 1973. The couple had four children: two sons, Don Evan Brown (December 25, 1916 – October 8, 1942; Captain in the United States Army Air Force, who was killed in the crash of an A-20B Havoc bomber while serving as a ferry pilot)[8] and Joe LeRoy "Joe L." Brown (September 1, 1918 – August 15, 2010), and two daughters, Mary Katherine Ann (b. 1930) and Kathryn Francis (b. 1934). Both daughters were adopted as infants.

Joe L. Brown shared his father's love of baseball, serving as general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955 to 1976, and briefly in 1985, also building the 1960 and 1971 World Series champions. Brown's '71 Pirates featured baseball's first all-black starting nine.

Brown began having heart problems in 1968 after suffering a severe heart attack, and underwent cardiac surgery. He died from arteriosclerosis on July 6, 1973 at his home in Brentwood, California, three weeks before his 82nd birthday. He is interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

For his contributions to the film industry, Brown was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960 with a motion pictures star located at 1680 Vine Street.

In 1961, Bowling Green State University renamed the theatre in which Brown appeared in Harvey in the 1950s as the Joe E. Brown Theatre. It was closed in 2011.

Holgate, Ohio, his birthplace, has a street named Joe E. Brown Avenue. Toledo, Ohio has a city park named Joe E. Brown Park at 150 West Oakland Street.

Rose Naftalin's popular 1975 cookbook includes a cookie named the Joe E. Brown.[14][15] Brown was a frequent customer of Naftalin's Toledo restaurant.

Flatrock Brewing Company in Napoleon, Ohio offers several brown ales such as Joe E. Coffee And Vanilla Bean Brown Ale, Joe E. Brown Hazelnut, Chocolate Peanut Butter Joe E. Brown, Joe E Brown Chocolate Pumpkin, and Joe E. (Brown Ale).

#joe e. brown#classic hollywood#classic movie stars#golden age of hollywood#old hollywood#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood#1950s hollywood#1960s hollywood#comedy legend

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monsters of the 20th Century

I had this odd notion. A (brief) analysis of the origin of various supernatural creatures, as I wondered what ‘new’ monsters/supernatural beings had been created in the 20th century (roughly). I’ve completed some of the research, and I’d like to share it with you all. I’m also gonna tag @tyrantisterror because he is one of the more knowledgable people about monsters I know about on tumblr and I’m sure he can correct me a bunch in this!

1. Frankenstein - 1817 - The oldest literary monster and outgrowth of the concept of the Homunculus and Golem as an artificial being. So pervasive is its reach, western ideas of Tulpa are tainted by it (every time you read about a tulpa ‘going out of control’, that is the influence of Frankenstein).

2. Dinosaurs - The Dragons of the age of science entered pop culture in 1854 at the latest with the opening of the Crystal Palace Park. Other prehistoric animals had captured people’s imagination before, and they didn’t start to enter fiction until 1864 (”Journey to the Center of the Earth”) and a short story by C. J. Cutliffe Hyne had an ancient crocodilian in his story “The Lizard” (1898). Ann early Lost World style adventure, “A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder” by James De Mille in 1888 has the first true dinosaurs in them. There, Antarctica has a warm spot where prehistoric monsters and a death cult lurk. In 1901, Frank Mackenzie Savile’s “Beyond the Great South Wall” had a Carnivorous Brontosaurs worshiped by Mayan remnants. “Panic in Paris” by Jules Lermina had dinosaurs attack a city, but it was published first in France so few saw it. Finally, we have Conan Doyle in 1912 with “The Lost World” which solidified dinosaurs as a thing in fiction.

3. The Evolved Man/Mutants - After “The Origin of Species” is published, it wasn’t long until Evolved Men or Mutants started showing up in fiction. “The Coming Race” and (1871), “The Great Romance” (1881). They are generally big-headed and often have ESP of some sort. In “Media: A Tale of the Future” (1891), they can control electricity too. It wasn’t until 1928 (”The Metal Man” by Jack Williamson) that Radiation was thrown in as a cause for Mutation. Cosmic Rays would follow in “The Man Who Evolved” by Edmond Hamilton (1931). After that, we have “Gladiator” by Philip Gordon Wylie (1930) where we have an engineered “Evolved Man”, and “Odd John” by Olaf Stapeldon which grants us the term “Homo superior” followed by “Slan” by A.E. van Vogt which has Evolved Humans as a persecuted minority. And with that, everything that makes the X-Men what they are is collected.

3. Man-Eating Tree - First reported in 1874, the idea of man-eating plants grew since then to encompase many monsters, but started as Folklore about ‘Darkest Africa” (Madagascar) in the New York World. They’d print anything back then.

4. Hyde - While it is tempting to link him to Freudian Psychology, Freud did not publish his work regarding things like the Id until much later (he didn’t even coin “Psychoanalysis” until 1896). What is springs from, I currently cannot say without more research.

4. Robot - Though there were automata since the days of the Greeks (Talos), the first Robot in modern fiction is from “The Future Eve” by Auguste Villiers de I’lsle Adam (1886). THough the term Robot is not invented until 1920 with “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” They definitely offshoot from Frankenstein, but with a more mechanical bent.

5. The Grey Alien - The modern idea of an Alien has it’s first antecedents in the 1800s. Specifically with the essay “Man of the Year 1,000,000″ by H. G. Wells (1892-1893). He speculates what humans will evolve into, and basically invites the Gray by accident. It wouldn’t achieve it’s alien attachments until much later.

6. Morlocks - With the Evolved Man, there is also the ‘Devolved Man’. That is what the Morlocks are. They are, as the name implies, tied to Well’s “The Time Machine” (1895), and the word has become a catch-all for subterranean monster-men, be they Mole People, CHUDs, or straight up Demons (’GvsE’).

7. The Martians & Their War Machines - The First Alien Invader, and the first Mecha can be traced to “War of the Worlds” by H.G. Wells, 1897. Not much more to say as far as I’m aware.

8. The Mummy - The 1800s saw an Egyptian craze in England, leading to some really nasty habits (google “Mummy Powder” if you need ipecac). 1827 saw “The Mummy!: Or, a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century” which is more a bit of futurism with an ancient protagonist. Though “Lost in the Pyramid” (1868) by Louisa May Alcott predates it, it is overshadowed by Conan Doyle’s horror story “Lot No. 249″ (1892) which has the classically animated mummy going out and killing people under control of another. The former is a “Curse” story rather than a monster.

9. Cordyceps - Everyone these days knows the Cordyceps fungus as a great source for making zombies, and I’m lumping that fungus in with these other monsters because, well, fungus’ that take over humans is a monster of the 20th century. Best known for Toho’s film adaptation “Matango” (1963), it is inspired by a short story from 1907 by William Hope Hodgson called “The Voice in the Night”. There, the poor victim doesn’t realize they’ve completely become a fungus monster, acting as a warning for those near the island.

10. Aerofauna - Conan Doyle strikes again with “The Horror of the Heights” (1912). A pretty tight little horror story of a whole ecosystem high above our heads in the clouds. Many a sky tentacle owes its existence to this one.

11. Lich - Possibly derived from Kosechi the Deathless of Russian folklore, the idea of undead sorcerers became a staple of the works of Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and Clark Ashton Smyth, dating back to 1929. Though Gary Gigax coined the idea together for D&D and based it on Gardner Fox’s “The Sword of the Sorcerer (1969)

12. Bigfoot and The Loch Ness Monster - I lump these cryptids together, because (thanks to a ton of research by Daren Naish, Daniel Loxton, Donald R. Prothero, and others) we can trace them back to the same source: King Kong (1933). The idea of prehistoric animals being out in the world in hidden places goes back to Conan Doyle’s “Lost World” (1912), but Kong made it widely popular. And between the giant ape and the Brontosaurus attack (and the timing of sightings picking up), we can blame Kong for this.

13. The Great Old Ones - Lovecraft’s primary contribution to fiction first appear in “The Call of Cthulhu” (1926) and expand upon from here. As near as I can tell, he made a LOT of monsters. These include “Ancient Aliens” & Shoggoths (1936 - “At the Mountains of Madness”), Gillmen (1931 - ”The Shadow over Innsmouth”), & The Colour Out of Space (1927). 14. The Thing - The Ultimate Shapeshifter. It first appears in 1938′s “Who Goes There” by John W. Campbell, Jr. Though Campbell's square-jawed heroes literally tear the Thing to bits, it reached its zenith of horror in adaptation. I can think of no earlier shapeshifting humanoids of such variety at an earlier time, or of such fecundity.

15. The Amazons - The Amazons do indeed come from Ancient Greece, but it was a way for the Greeks to rag on Women. It wasn’t until later that women co-opted the image of the Amazons as a source of empowerment, and that was codified in 1942 with one character: Wonder Woman. She helped spark the Amazons further into the culture, or at least, Amazon women who have superpowers (as they did in those early stories). From there, we get a more recent direct descendant that was part of the reason I started this list: Slayers from “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.”

16. The Hobbit - Though ideas of ‘Wee Folk” are part of worldwide Folklore, Tolkien took them out of the realm of Faerie, and made them... idyllic middle-class Englishmen with his 1937 book of the same name. With the Lord of the Rings following in 1954-1955. His works also gave us other monsters and supernatural beings: Orcs, Ents, & Balrogs.

17. Gremlins - An Evolution of the wee folk once again, this time adapted for the mechanical era and of a more malicious bent. It became slang in the 1920s, with the earliest print source being from 1929. They were popularized by Roald Dahl in”The Gremlins” (1942). Later they were used to vex Bugs Bunny (1943′s “Falling Hare”), and then they got their own movies in the 1980s. The rest is history.

18. Triffids - There are a LOT of fictional plants out there, and a lot of carnivorous ones, but the Triffids were the first to be extremely active in their pursuit of prey. From 1952′s “Day of the Triffids” by John Wyndham, the story is a keen example of the ‘Cozy Apocalypse’ common in British Fiction, sort of like the whole ‘schoolboys on a desert island make well of it’ thing that “Lord of the Flies” railed against. This paved the way for everything from Audrey II to Biollante.

19. Kaiju - 1954. You know what this is. Between Primordial Gods and Modern Technology, the Kaiju are born. The difference between a Kaiju and a Giant Monster is a complex nuanced one, sort of like what makes film noir. But, in general, if the story has Anti-War, Anti-Nationalist, and/or Anti-Corporate Greed leanings, it’s probably a Kaiju movie. If not, then it probably isn’t.

20. The Body Snatchers - Another horror of 1954 from the novel “The Body Snatchers” (1955), which includes aspects that the movie “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” did not. Like that the Duplicates only last 5 years and basically exist to wipe out sentient beings with each planet they infest. Clearly drawing from the idea of the Doppelganger, these Pod People have evolved into a new form.

21. The Blob - That 1958 movie has one catchy theme song. The whole thing was inspired by an instance of “Star Jelly” in Pennsylvania, circa 1950. It was tempting to shift this under the Shoggoth, but I think they are distinct enough.

22. Gargoyles - Longtime architectural embellishments, they did not become their own “Being” until 1971 with “The Living Gargoyle” published in Nightmare #6. The TV Movie “Gargoyles” came soon after in 1972, firmly establishing the monster. Though it was likely perfected in the TV Series “Gargoyles” (1994).

23. D&D - From 1973 Through 1977, D&D was formulated and many of its key monsters were invented. Partly as mechanics ways to screw with players and keep things lively. This brought us Rust Monsters (1973), Mindflayer (1974), Beholder (1975), and the Gelatinous Cube (1977).

24. The Xenomorph - Parasitoid breeding is applied to humans to wonderfully horrible effect in the 1979 film “Alien”. It became iconic as soon as it appeared.

25. Slasher - The first slasher film is often considered to be ‘Psycho’ (though the Universal Mummy films beyond the first prototype the formula). The idea of an undead revenant coming back to kill rather randomly started in the film “The Fog” (1980), but was codified by Jason Voorhees in either 1984 or 1986. I am no expert on this one, though, so I am not fully certain.

26. The Dream Killer - Freddy Krueger first appeared as a killer in dreams in 1981, but there were other dream killers before him. They could only kill with extreme fear, though. Freddy got physical! I think. Again, more research is needed.

27. Chupacabras - This is another cryptid inspired by a movie. In this case, “Species” (1995). No, really. This is what it comes from. I know a lot of these are really short down the line, but the research for this one is thorough and concise!

28. Slender Man - The Boogieman for the Internet Age. An icon of Creepypastas and emblem of them.

Needs More Research: The Crow/Heroic Longer-Term Revenants, Immortals as a “Group” (might go to Gulliver's Travels, but I’m trying to track Highlander here) are also on the list, but they are proving extremely difficult to research, so I thought I’d post what I have at the moment. Shinigami might also be on the list since they are syncretic adoption of the Grim Reaper into something more.

#Monsters#Folklore#Fiction#Frankenstein#Mr. Hyde#Mummy#Aliens#Morlock#Alien#Martian#War of the Worlds#matangeshwara temple#Dinosaurs#Aerofauna#Robot#Gremlin#Old Ones#Cthulhu#Tolkein#Lovecraft#Lich#Gargoyles#Loch Ness#Bigfoot#king kong#Kaiju#Amazon#Buffy the Vampire Slayer#D&D#Slasher

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marshall McLuhan’s social criticism

“Blondie and her children own America, control American business and entertainment, run hog-wild in spreading materialism into education and politics,” he insisted. The traditional order in which man upholds a rational authority and is sustained by the emotional support of his wife had been overturned. The only cure was for Dagwood to reclaim “the detached use of autonomous reason for the critical appraisal of life”--in other words, to invoke the combined spirits of St. Thomas Aquinas and F.R. Leavis--and to engage in “healthy and fructifying work,” that is, to give Mr. Dithers his notice and sign up in the wheelwright’s shop that Leavis so admired in Culture and Environment.

McLuhan was happy to see the article exposed to a relatively large readership (half a million circulation), but he was worried that it appeared in a Roman Catholic magazine. He wanted to prove himself in the larger world of scholarship before making a public appearance under such auspices. To become identified as a Catholic intellectual at the start of his career seemed unwise. Far better to act, like his opposite number, the dedicated Communist, as a sort of mole in the academic world, swaying minds that might be repulsed if one’s affiliations were made obvious.

McLuhan definitely wanted to sway minds with this theme. He had visions of expanding “Dagwood’s America” into a book, which he tentatively titled Sixty Million Mama’s Boys. He thought such a book might prove a hit as a piece of “impudent” pop sociology along the lines of Generation of Vipers, Philip Wylie’s 1942 best-selling attack on “momism”--though of course McLuhan’s book would be far more profound than Wylie’s.

The implicit antifeminist message of this book (which was never published) and of the Dagwood theme in general consorted, in those years, with McLuhan’s persistent suspicion of homosexuals, overt and closeted. In 1949, Felix Giovanelli wrote him about Gershon Legman, a mutual acquaintance who was an authority on Freud. Legman, Giovanelli reported, was as wary of homosexuals as McLuhan was and held the same belief that they lurked everywhere in places of cultural influence. Giovanelli implied that Legman was another ally in the struggle to alert the public to this unhappy situation, which was first hinted at in a 1931 book McLuhan had studied, The Diabolical Principle, by the painter and writer Wyndham Lewis. In it, Lewis suggested that the “homosexual cult” was a direct result of the feminist revolt.

In McLuhan’s eyes, Dagwood, the mama’s boy, and the homosexual were closely related figures. Grand sociological theories aside, he had been horrified by the “homosexual cult” since his Cambridge years and retained throughout his life the repugnance of a strait-laced Methodist child for homosexual activity. During his later years he was very careful to keep his opinion to himself, but throughout the 1940s his distaste was transmuted into a significant, if discreet, motif of his social criticism. He feared that male homosexuality was rampant in the age, the result of Blondie’s emasculating Dagwood in front of Cokie and Alexander, their children. Such homosexuality was probably the chief threat to contemporary morality.

McLuhan tried to publish his social criticism in general-interest magazines. During the war, he submitted an article entitled “Is Postwar Polygamy Inevitable?” to Esquire magazine. His argument was that the increasing prevalence of divorce, sexual promiscuity, adoption of illegitimate children, and artificial insemination had already removed any aura of sanctity from monogamy and the bearing of children by monogamous parents. In addition, the dynamics of industrial and commercial life, reducing both men and women to the status of wage-slaves and consumers, were making the traditional monogamous family an economic luxury. Men could no longer support families in proud independence. McLuhan’s prediction was that women, who were “constitutionally docile, uncritical and routine-loving,” would take over the running of commerce, industry, and government, collectively supporting a class of male loafers and warriors, in the manner of certain primitive tribes.

The argument is not entirely clear--it was certainly impenetrable to the editors of Esquire, who promptly rejected the article. It does reveal, however, an uncanny anticipation of our present era of even greater divorce and promiscuity, massive participation of women in the work force, single-parent families, surrogate motherhood, universal daycare, and other post-monogamy phenomena....

McLuhan’s greatest successes were the articles that combined the culture and environment strain of social criticism with the literary perspective of his trivium studies. The first of these was “Edgar Poe’s Tradition,” published in the Sewanee Review in 1944. In this essay, McLuhan placed Poe in the tradition of rhetoric, of Cicero and the Renaissance humanists, which he believed took root in the American South. The result of that tradition, according to McLuhan, was Poe’s naturally cosmopolitan and aristocratic outlook, his high standards of literature, and his ideal of a society informed and led by men of wide learning, political savvy, and eloquence.

He expanded this theme in a series of essays for the Sewanee Review over the next few years. In “The Southern Quality” he elaborated on the southern tradition, associating it not only with Renaissance humanism and the study of rhetoric but with a way of life that was based on agriculture, communal living, and aristocratic values. Opposed to this was the tradition of New England, associated wth dialectics--utilitarian logic--and a way of life that was commercial and industrial, based on aggressive individualism. The southern tradition obviously encompassed many of the qualities he would later describe as “acoustic” and the northern tradition qualities he would describe as “visual,” although he was not yet thinking in those terms.

As always in his writings, there was no doubt which tradition he favoured. McLuhan’s admiration for the American South was a product not only of living with a wife who had an inextinguishable east Texas accent but of a genuine regard for the civilization that Jefferson had attempted to nurture. McLuhan was impressed by Jefferson, the aristocrat who was a scholar and a gentleman. Wholly free of any snobbery himself, he found immensely attractive anyone who was courtly, respectful of tradition, self-possessed, and also deeply responsible.

In “Footprints in the Sands of Crime,” McLuhan cited Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin, Sherlock Holmes, Lord Peter Wimsey, and other notable sleuths as beloning to the gentlemanly and erudite tradition of Cicero and the Renaissance rhetoricians and humanists. The direct lineage of the sleuth was through aristocratic dandies such as Byron and Baudelaire, with a bit of the man-hunting noble savage of James Fenimore Cooper thrown into the gene pool. The significance of the sleuth was his utter contrast, given such a lineage, wth the commercial society around him and with its paid functionaries, the police. While McLuhan had no admiration for either the style of the substance of detective fiction, he maintained an ongoing fascination for the sleuth figure and once allowed himself to be photographed in a Sherlock Holmes outfit. He saw his own work with the media as an example of sleuthing, the relentless search for the telltale clue.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

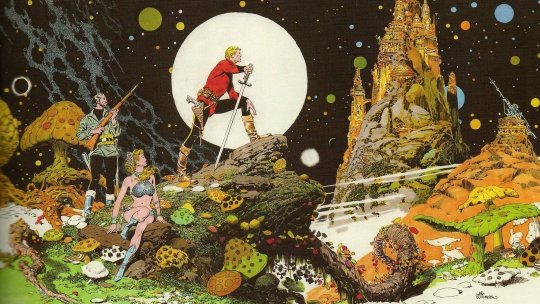

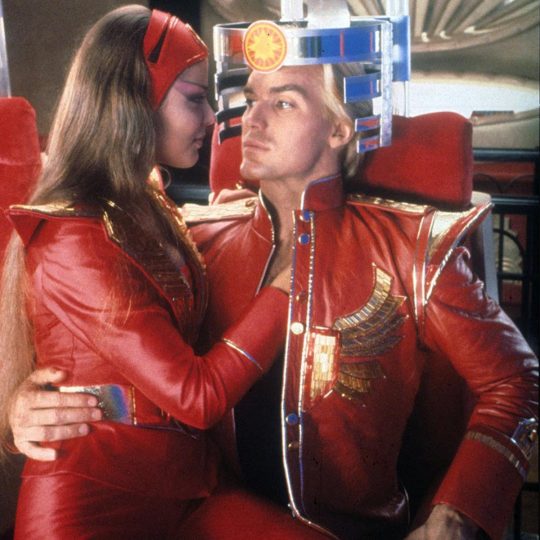

FLASH GORDON

Em 1931, Edgar Rice Burroughs fazia tiras de Tarzan para a distribuidora United, e queria também que fosse públicado uma tira baseada em seus romances passados em Marte, cujo personagem principal era John Carter, mas seu editor no ano seguinte, acabou reijetando a proposta, alegando que uma nova tira afastaria as atenções de Tarzan, que ainda estava tentando se consolidar na época. No entanto em 1933 a rival King Features se aproximou de Edgar e propôs que um jovem desenhista chamado Alex Raymond e o escritor Don G. Moore criassem uma série de histórias baseadas nas aventuras de John Carter.

No fim Raymond e Moore acabaram criando o herói "Flash Gordon", mas Raymond acabou criando também X-9 e Jim da Selvas, que eram clones de Dick Tracy e Tarzan de Burroughs, o que acabou chateando demais ele, no fim das contas Flash Gordon acabou estreiando numa página dominical, em 7 de janeiro de 1934. Flash é o jovem atleta de Yale que, junto com Dale Arden, é obrigado pelo Dr. Zarkov a embarcar junto com ele em sua nave rumo ao planeta Mongo, o desconhecido mundo está em rota de colisão com a Terra e o cientista acredita que só o impacto do veículo é capaz de mudar o curso do planeta Mongo, essa sequência inicial foi baseada no livro "When worlds collide", de Edwin Balmer e Philip Wylie.

Em 1935, as tiras de quadrinhos foram adaptas para a série radiofônica The Amazing Interplanetary Adventures of Flash Gordon, que durou 26 episódios e seguiu com bastante fidelidade a versão impressa, exceto pelos dois últimos episódios, onde Flash se encontra com Jim das Selvas, o primeiro romance baseado nas tiras, Flash Gordon in the Caverns of Mongo, foi públicado em 1936 por Grosset e Dunlap, o autor foi Alex Raymond, em 1973, a Avon Books lançou uma série em seis volumes de romances de Flash Gordon para adultos: The lion Men of Mongo, The Plague of Sound, The Space Circus, The Time Trap of Ming XIII, The Witch Queen of Mongo, The Plague of Sound, The Space Circus, The Time Trap of Ming XIII, The Witch Queen of Mongo e The War of the Cybernauts, em 1980 a editora Temp também lançou outros seis volumes.

Na questão de animação, em 1979, a Filmation produziu uma série em desenho animado baseada nas histórias em quadrinhos, e sua primeira temporada é lembrada como um dos melhores trabalhos do estúdio, em 1988, a DC Comics produziu uma versão modernizada nos quadrinhos, ela apresentava Flash como um jogador de basquete que encontra um novo próposito de vida em Mongo, o qual não representa uma ameaça para a Terra, a série teve 9 edições, o que tinha sido planejado. Em 1995, a Marvel Comics lançou uma série em duas edições com arte de Al Williamson, no estilo das HQs de Flash que ele havia feito para a King e outros, em 1936. Nenhuma dessas edições fez sucesso, acabando ficando mais para colecionadores de revistas pulp.

Em 1980, é lançado o filme de Flash, com a seguinte sinopse, "um jogador de futebol, conhecido como Flash Gordon e seus amigos viajam acidentalmente para um planeta chamado Mongo e acabam lutando contra a tirania do imperador Ming para salvar a terra". O filme foi dirigido por Mike Hodges, seu elenco tinha a participação de:

Sam J. Jones como Flash Gordon Max Von Sydow como Imperador Ming Melody Anderson como Dale Arden Ornella Muti como Princesa Aura Timothy Dalton como Príncipe Barin Brian Blessed como Príncipe Vultan Mariangela Melato como Kala Kenny Baker como Duende

O filme têm um visual retrô e figurino bem brega, o filme se tornou um clássico apesar de ser bem mal feito, e vou te dizer esse filme têm aquele visual que te atrai e te decepciona ao mesmo tempo, poucos filmes têm essa suposta "habilidade", o que marca mesmo nesse filme é a trilha sonora composta pelo Queen, pois é não é pra qualquer um mesmo, o que têm que ficar claro é que o filme tem seu charme mesmo que as atuações horriveis, efeitos especiais ruins até para sua época, o que vemos não é uma releitura mas sim uma homenagem aos quadrinhos e isso que realmente marca esse filme como um clássico.

Eu poderia escrever mil detalher aqui para vocês sobre o filme, mas na real o filme é ruim, em muitos conceitos mas eu te aconselho a assistir por que é dificil ver um filme que te de uma diversão tão grande a ponto de te levar para sua infância e te fazer sentir como uma criança colocando uma fita cassete para reproduzir na sua tv gigantesca de tubo e se sentando em frente dela comendo bolacha (ou biscoito).

Algumas coisas que vocês devem saber sobre Flash Gordon, ele é diretamente responsável pela chegada do homem à lua, na sua primeira página de 1934, Flash sai da Terra em direção ao planeta Mongo em um foguete lançado verticalmente, mais de vinte e cinco anos ates do Cabo Canaveral. O formato e a dimensão do foguete criado por Zarkov, serviu de base para a criação dos primeiros protótipos da Nasa, tubos de oxigênio, roupas adaptáveis e milhões de outras tecnologias aparecerem em Flash Gordon antes de serem inventadas no mundo real.

George lucas era um grande fã dos seriados de Flash e certa vez tentou adaptá lo, porém nenhum dos produtores se interessou pela ideia, então ele resolveu escrever Star Wars baseando se em vários elementos dos seriados, graças a Deus ele criou Star Wars. Durante algumas páginas em 1936, Flash foi transformado em um ser submarino, sua transformação serviu de base para a criação de diversos heróis submarinos como Namor e Aquaman. Flash Gordon perdeu sua fama nos anos 90, mas sua mensagem se eternizou, um homem não abandona seus amigos, busca sempre a justiça e faz de tudo para que as pessoas abandonem a maldade e se transformem em grandes aliados.

"Um verdadeiro príncipe não foge do perigo"

0 notes

Photo

Science Fiction Books Released Pre-WWII

This is a list of classic science fiction books released before Steve Rogers went into the ice (1945). They are books that Steve and Bucky potentially read before waking up in the 21st century. Books released after 1942 would likely not have been read by Steve or Bucky, as from 1943 they were in the USO or in active service, and in 1942 these would have been new-releases, and the boys were in basic training for much of the year, so there is a low likelihood that they would have read them. The purpose of the list is to highlight books and their cultural references that Steve (and Bucky) would already be familiar with in the 21st century.

Also, see the Science Fiction Books Released Post-WWII list — as well as the Classic Book Release lists from Pre-WWII and Post-WWII.

While not exhausted by any stretch, the list includes many best sellers, as well as books which contain popular cultural references or those with notable social commentary. Some stories included are those that appeared in pulp magazines before the war, but which were not published as books until later. If they read Astounding Stories magazine then that may have read these titles. Feel free to suggest other titles you think Steve or Bucky might have read — please include an explanation for the choice.

1800s - 1942

Frankenstein - Mary Shelley | 1818

A Journey to the Centre of the Earth - Jules Verne | 1864

From the Earth to the Moon - Jules Verne | 1865

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea - Jules Verne | 1870

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthurs Court - Mark Twain | 1889

The Time Machine - H.G. Wells | 1895

The Invisible Man - H.G. Wells | 1897

The War of the Worlds - H.G. Wells | 1898

With the Night Mail - Rudyard Kipling | 1908

The Machine Stops - E.M. Forster | 1909

The Hampdenshire Wonder - J.D. Beresford | 1911

Locus Solus - Raymond Roussel | 1914

Herland - Charlotte Perkins Gilman | 1915

A Princess of Mars - Edgar Rice Burroughs | 1917

The Moon Pool - A. Merritt | 1919

When The World Shook - H. Rider Haggard | 1919

The Amphibians - S. Fowler Wright | 1925

Heart of a Dog - Mikhail Bulgakov | 1925

Metropolis - Thea von Harbou | 1926 (1927 in English)

The Moon Maid - Edgar Rice Burroughs | 1926

The Color Out of Space - H.P. Lovecraft | 1927

The Skylark of Space - E.E."Doc” Smith | 1928

Gladiator - Philip Gordon Wylie | 1930

The Last and First Men - Olaf Stapledon | 1930

Brave New World - Aldous Huxley | 1932

When Worlds Collide - Edwin Balmer and Philip Wylie | 1933

The Legion of Space - Jack Williamson | Serialised in Astounding Stories in 1934

Tiriplanetary - E.E. “Doc” Smith | Serialised in Amazing Stories in 1934

Odd John - Olaf Stapledon | 1935

At the Mountains of Madness - H.P. Lovecraft | In Astounding Stories in 1936

The Shadow Over Innsmouth - H.P. Lovecraft | 1936

War with the Newts - Karel Čapek’ | 1936

Star Maker - Olaf Stapleton | 1937

Out of the Silent Planet - C.S. Lewis | 1938

i, Robot - Isaac Asimov | Serialised between 1940-1950

Stan - A.E. van Vogt | Serialised in Astounding Stories in 1940

The Encyclopedists (1942); Bridle and Saddle (1942): Original stories that later became the beginning of the Foundation Series - Isaac Asimov | Serialised in Astounding Stories between 1942-1950

Also in this set: Book Released Post-WWII, Book Released Pre-WWII, Science Fiction Books Released Post-WWII

Images

Frankenstein, 1931 | Source At the Mountain of Madness, 1936 | Source Brave New World, 1932 | Source Metropolis, 1926 | Source

References

#Steve Rogers#Captain America#Science Fiction#Sci-Fi#Books#Sci Fi#Sci Fi Classics#historically accurate#Bucky#Bucky Barnes#james bucky barnes#fanfic references#captain america reference#Captain America: The First Avenger#captain america tfa

31 notes

·

View notes