#Women in science

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

45K notes

·

View notes

Text

HIYA.

So a lot has gone on in the last little bit. NASA recently was ordered to scrub their site of women's contributions to astronomy and astrophysics, even took down their page celebrating women's history month and all the contributions they've made to NASA. So I did a thing and crawled through the wayback machine to find some articles, and decided to put this right here because fuck the government, fuck the orange in charge who told them to scrub their site, and fuck NASA for throwing their people under the bus and bowing to this authoritarian nonsense. This version of the site still has articles on some important figures like Eileen Collins, the first woman to command a space shuttle, and ISS chief scientist Jennifer Buchli and chief deputy scientist Meghan Everett, who, in their words, "-provide the science strategy and make science recommendations for the International Space Station program, and help make sure all of the science on the International Space Station goes smoothly, from preparing for launch to conducting research on the space station with the scientists and astronauts and returning the science to Earth."

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Join us in celebrating Women's History Month with Ellen, our senior aquarist who does incredible work with sunflower stars at the Aquarium! 🌟

These once-abundant predators played a key role in keeping Monterey Bay kelp forests healthy, but Sea Star Wasting Disease brought them to the brink of extinction.

We're partnering with amazing organizations like the California Academy of Sciences, Aquarium of the Pacific, Birch Aquarium at Scripps, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and the Sunflower Sea Star Lab to bring them back.

Learn more about our efforts and how we're growing sunflower stars from tiny babies to giant sea stars!

#kelp us save stars#women in science#women's history month#here comes the sun for the stars#stellar women in STEM

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Greek Women Mathematicians you didn't know about

Αίθρα - Aethra (10th - 9th century BC), daughter of the king of Troizina Pitthea and mother of Theseus, knew mathematics in another capacity unknown to many. So sacred to the beginnings of the most cerebral science, Aethra taught arithmetic to the children of Troizina, with that complex awe-inspiring method, since there was no zero… and the numbers were symbolically complex, as their symbols required many repetitions.

Πολυγνώτη - Polygnoti (7th - 6th century BC) The historian Lovon Argeios mentions Polygnotis as a companion and student of Thalis. A scholar of many geometric theorems, it is said in Vitruvius' testimony, that she contributed to the simplification of arithmetic symbols by introducing the principle of acrophony. She managed this by introducing alphabetic letters that corresponded to each in the initial letter of the name of the number. Thus, Δ, the initial of Δέκα (ΤΕΝ), represents the number 10. X, the initial of Χίλια (Thousand), represents the number 1000 etc. According to Vitruvius, Polygnoti formulated and first proved the proposition "Εν κύκλω η εν τω ημικυκλίω γωνία ορθή εστίν" - "In the circle the angle in the hemi-circle is right angle."

Θεμιστόκλεια - Themistoklia (6th century BC). Diogenes the Laertius scholar-writer mentions it as Αριστόκλεια - Aristoclia or Θεόκλεια - Theoclia. Pythagoras took most of his moral principles from the Delphic priestess Themistoclia, who at the same time introduced him to the principles of arithmetic and geometry. According to the philosopher Aristoxenos (4th century BC), Themistoclia taught mathematics to those of the visitors of Delphi who had the relevant appeal. Legend has it that Themistoclia decorated the altar of Apollo with geometric shapes. According to Aristoxenos, Pythagoras admired the knowledge and wisdom of Themistoclia, a fact that prompted him to accept women later in his School.

Μελίσσα - Melissa (6th century BC). Pupil of Pythagoras. She was involved in the construction of regular polygons. Lovon Argeios writes about an unknown work of hers: "Ο Κύκλος Φυσίν - η Μελίσσα - Των Εγγραφομένων Πολυγώνων Απάντων Εστί". (The title translates to "The circle is always the basis of the written polygons" or so.)

Τυμίχα - Tymicha (6th century BC). Thymiha, wife of Crotonian Millios, was (according to Diogenes Laertius) a Spartan, born in Croton. From a very early age, she became a member of the Pythagorean community. Iamblichus mentions a book about "friend numbers". After the destruction of the school by the Democrats of Croton, Tymicha took refuge in Syracuse. The tyrant of Syracuse, Dionysios, demanded that Tymicha reveal to him the secrets of the Pythagorean teaching for a great reward. She flatly refused and even cut her own tongue with her teeth and spat in Dionysius' face. This fact is reported by Hippobotus and Neanthis.

Βιτάλη - Vitali or Vistala (6th – 5th century BC). Vitali was the daughter of Damos and granddaughter of Pythagoras, and an expert in Pythagorean mathematics. Before Pythagoras died, he entrusted her with the "memoirs", that is, the philosophical texts of her father.

Πανδροσίων ή Πάνδροσος - Pandrosion or Pandrossos (4th century AD). Alexandrian geometer, probably a student of Pappos, who dedicates to her the third book of the "Synagogue". Pandrosion divides geometric problems into three categories:" Three genera are of the problems in Geometry and these, levels are called, and the other linear ones."

Πυθαΐς - Pythais (2nd century BC). Geometer, daughter of the mathematician Zenodoros.

Αξιόθεα - Axiothea (4th century BC). She is also a student, like Lasthenia, of Plato's academy. She came to Athens from the Peloponnesian city of Fliounda. She showed a special interest in mathematics and natural philosophy, and later taught these sciences in Corinth and Athens.

Περικτιόνη - Periktioni (5th century BC). Pythagorean philosopher, writer, and mathematician. Various sources identify her with Perictioni, Plato's mother and Critius' daughter. Plato owes his first acquaintance with mathematics and philosophy to Perictioni.

Διοτίμα - Diotima from Mantineia (6th-5th century BC). In Plato's "Symposium", Socrates refers to the Teacher of Diotima, a priestess in Mantineia, who was a Pythagorean and a connoisseur of Pythagorean numerology. According to Xenophon, Diotima had no difficulty in understanding the most complex geometric theorems.

Iamblichos, in his work "On Pythagorean Life", saved the names of Pythagorean women who were connoisseurs of Pythagorean philosophy and Pythagorean mathematics. We have already mentioned some of them. The rest:

Ρυνδακώ - Rynthako

Οκκελώ - Okkelo

Χειλωνίς - Chilonis

Κρατησίκλεια - Kratisiklia

Λασθένια - Lasthenia

Αβροτέλεια - Avrotelia

Εχεκράτεια - Ehekratia

Θεανώ - Theano

Τυρσηνίς - Tyrsinis

Πεισιρρόδη - Pisirrodi

Θεαδούσα - Theathousa

Βοιώ - Voio

Βαβέλυκα - Vavelyka

Κλεαίχμα - Cleaihma

Νισθαιαδούσα - Nistheathousa

Νικαρέτη - Nikareti from Corinth

There are so many women whose contribution to science remains hidden. We should strive to find out about more of them! For more information, check out the books of the Greek philologist, lecturer, and professor of ancient Greek history and language, Anna Tziropoulou-Eustathiou.

#I noted those names down from different sources and I copied a few more info from a comment under a video#international women's day#science#history#mathematics#pythagoras#greek women#greek history#hellas#women in stem#women in science#women in mathematics#Pythagorean mathematics#women's history

749 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Girl Scout Day! March 12, 2024, is the 112th birthday of Girl Scouts in the United States, and to celebrate, we’re sharing a lithograph of the Girl Scout alumnae who became NASA astronauts.

Girl Scouts learn to work together, build community, embrace adventurousness and curiosity, and develop leadership skills—all of which come in handy as an astronaut. For example, former Scouts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir worked together to make history on Oct. 18, 2019, when they performed the first all-woman spacewalk.

Pam Melroy is one of only two women to command a space shuttle and became NASA’s deputy administrator on June 21, 2021.

Nicole Mann was the first Indigenous woman from NASA to go to space when she launched to the International Space Station on Oct. 5, 2022. Currently, Loral O’Hara is aboard the space station, conducting science experiments and research.

Participating in thoughtful activities in leadership and STEM in Girl Scouts has empowered and inspired generations of girls to explore space, and we can’t wait to meet the future generations who will venture to the Moon and beyond.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

#NASA#space#space exploration#Girl Scouts#adventure#explore#inspiration#inspirational women#Womens History Month#WHM#science#STEM#women in STEM#women in science#International Space Station#ISS#astronaut#tech#technology

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Chemist

#women in science#chemistry#leather pants#women in leather#girls in leather#girls wearing glasses#sexy glasses#sexy outfit#hot outfit#outfit of the day#cute outfit#big beautiful breasts#big natural breasts#hot bewbs#slutty outfit#slutty at work#feeling slutty#slutlife#natural tiddies#free the tiddy#free the bewbs#sexy bitch#sexy and beautiful#style inspo#fashion inspo#fashionista#sexy as f..k#hot as fuuuuck#leather

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mission specialist Sally Ride aboard Space Shuttle Challenger, STS-7

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

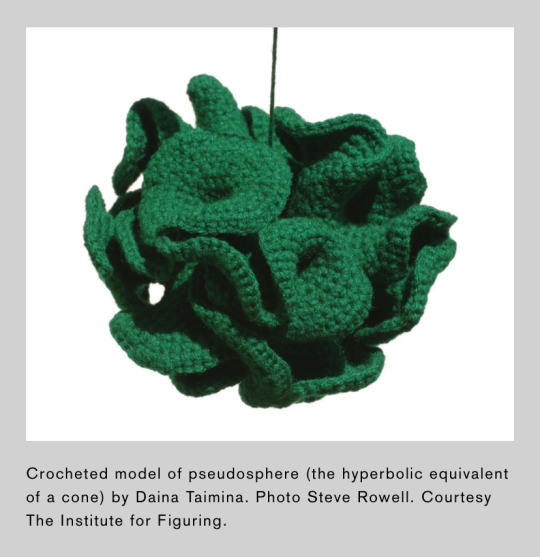

It took about two hours for Daina Taimina to find the solution that had eluded mathematicians for over a century. It was 1997, and the Latvian mathematician was participating in a geometry workshop at Cornell University. David Henderson, the professor leading the workshop, was modelling a hyperbolic plane constructed out of thin, circular strips of paper taped together. 'It was disgusting,' laughed Taimina in an interview.

A hyperbolic plane is 'the geometric opposite' of a sphere, explains Henderson in an interview with arts and culture magazine Cabinet. 'On a sphere, the surface curves in on itself and is closed. A hyperbolic plane is a surface in which the space curves away from itself at every point.' It exists in nature in ruffled lettuce leaves, in coral leaf, in sea slugs, in cancer cells. Hyperbolic geometry is used by statisticians when they work with multidimensional data, by Pixar animators when they want to simulate realistic cloth, by auto-industry engineers to design aerodynamic cars, by acoustic engineers to design concert halls. It's the foundation of the theory of relativity, and thus the closest thing we have to an understanding of the shape of the universe. In short, hyperbolic space is a pretty big deal.

But for thousands of years, hyperbolic space didn't exist. At least it didn't according to mathematicians, who believed that there were only two types of space: Euclidean, or flat space, like a table, and spherical space, like a ball. In the nineteenth century, hyperbolic space was discovered - but only in principle. And although mathematicians tried for over a century to find a way to successfully represent this space physically, no one managed it - until Taimina attended that workshop at Cornell. Because as well as being a professor of mathematics, Taimina also liked to crochet.

Taimina learnt to crochet as a schoolgirl. Growing up in Latvia, part of the former Soviet Union, 'you fix your own car, you fix your own faucet - anything', she explains. 'When I was growing up, knitting or any other handiwork meant you could make a dress or a sweater different from everybody else's.' But while she had always seen patterns and algorithms in knitting and crochet, Taimina had never connected this traditional, domestic, feminine skill with her professional work in maths. Until that workshop in 1997. When she saw the battered paper approximation Henderson was using to explain hyperbolic space, she realised: I can make this out of crochet.

And so that's what she did. She spent her summer 'crocheting a classroom set of hyperbolic forms' by the swimming pool. 'People walked by, and they asked me, "What are you doing?" And I answered, "Oh, I'm crocheting the hyperbolic plane."' She has now created hundreds of models and explains that in the process of making them 'you get a very concrete sense of the space expanding exponentially. The first rows take no time but the later rows can take literally hours, they have so many stitches. You get a visceral sense of what "hyperbolic" really means.' Just looking at her models did the same for others: in an interview with the New York Times Taimina recalled a professor who had taught hyperbolic space for years seeing one and saying, 'Oh, so that's how they look.' Now her creations are the standard model for explaining hyperbolic space.

-Caroline Criado Perez, Invisible Women

Photo credit

#caroline criado perez#Daina Taimina#women in stem#women’s history#women in science#crochet#crocheting#female mathematicians#hyperbolic space

384 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caribbean reef squid are very enigmatic creatures and can be difficult to find during the day, thanks to their camouflage, but are much more easily spotted at night due to their reflective eyes and more bold attitude in the dark!

Most who are interested in cephalopods have heard of chromatophores (the cells responsible for their color-changing prowess) but lesser known are the iridophores that lay beneath that lend their skin unique reflective properties; their eyes are tightly packed with these cells, and give them their flashing-coin quality!

#sepioteuthis#squid#cephalopods#mollusks#invertebrate#marine biology#marine bio#biology#zoology#animals#nature#ocean#cute animals#marine science#video#scuba diving#scuba#women in science#women in stem#marine conservation#marine education#ocean science#ocean animals#invertebrate zoology

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

One week on Rota, dry season 2025.

#rota island#northern mariana islands#tropical forest#skull#mushrooms#fig tree#ecology#women in science

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1911, Marie Curie's affair with married physicist Paul Langevin sparked public outrage. Despite the Nobel Committee's suggestion to avoid the ceremony for her second Nobel Prize, she attended. Albert Einstein supported her, advising her to ignore the negative press.

#Marie Curie#Paul Langevin#Albert Einstein#Nobel Prize#Scandal#Resilience#Women in Science#Physics#Chemistry#History

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

We’re otterly excited to share that Executive Director Julie Packard is one of six finalists for the 2025 Indianapolis Prize–considered the world’s highest honor for wildlife conservation! 🦦💙

Julie has made waves in the sustainable seafood movement through creating Seafood Watch and has been a leading voice for science-based policy reform in support of a healthy ocean. The Aquarium is honored for this recognition and congratulates all the nominated finalists.

Visit the link below to learn more about the Indianapolis Prize. The recipient of the award will be announced in May!

#monterey bay aquarium#women in science#did you know julie is an algae biologist?#sealebrating action for the ocean

861 notes

·

View notes

Text

Natural inspiration

Martha Muñoz has shown that organisms can influence their own evolution—a lesson she’s passing on to her students

The southern Appalachians are a diversity hot spot for these creatures (lungless salamanders), but many of the roughly 30 species of lungless salamanders here look similar. Their environment also seems uniform, at least at first glance—creating a puzzle about how so many species could have evolved. Muñoz suspects subtle differences in behavior or habitat may have driven the salamanders to diversify, and she wants to figure out what they could be. ... At Harvard, she worked with evolutionary biologist Jonathan Losos, whose research on Caribbean anoles has become a classic example of how evolution can follow a predictable path. For decades Losos and his students have studied lizards introduced to new islands, finding that when faced with similar challenges, these newcomers often adapt by evolving similar characteristics...

Read more: https://www.science.org/content/article/biologist-discovered-lizards-and-other-organisms-can-influence-their-own-evolution

#evolution#salamander#lizard#amphibian#reptile#anole#plethodontidae#animals#nature#science#herpetology#women in science

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of my roman empires is beatrix potter because everyone knows she wrote the peter rabbit books but no one talks about how she studied lichens and fungi and was deeply involved in mycology like we wouldn’t know a lot about lichens without her

#beatrix potter#peter rabbit#women in science#shes so cool ive been crazy about her since i was 8#we need to talk about her more i fear

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Hamilton – Scientist of the Day

Alice Hamilton, an American physician, medical researcher, and social reformer, was born Feb. 27, 1869, in New York City.

learn more

#Alice Hamilton#medicine#women in science#industrial toxicology#histsci#histSTM#20th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

56 notes

·

View notes