#Wilhelmina Miami

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The beautiful Rhea Rai by me Ben Everden

#rhea rai#myphoto#girls#photographers on tumblr#model#ben everden#fashion#sunset#beach#swimwear#beauty#gorgeous#cute#beach babe#wilhelmina miami#wilhelmina

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

MSW: OH POLLY

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katelyn Gray

IG: KatelynMoya

Represented by Wilhelmina (Miami)

📷 Andre Dawn

768 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jess Watches // Wed 11 Sept // Day 349 Synopses & Favourite Scenes & Poll

Ugly Betty (rw with mum) 4x08 The Bahamas Triangle

In the steamy Bahamas, the love triangle between Betty, Matt and Amanda explodes, and romantic pairings abound. Things should be dreamy at the Atlantis resort, where even Shakira is staying, but Betty has a nightmarish photo shoot after Willie learns her nemesis, Penelope Graybridge, snagged a coveted job, and, even more importantly, discovers Connor is very much alive.

New York Wilhelmina: If anyone tells you there's something called "island time," drown them in their daiquiri and poke their eyes out with the umbrella.

Bahamas Willie, post-sex, tits out: It's island time, Betty. Jump on board, man.

Frasier (with mum) 6x16 Decoys

Donny is now going out with Daphne, which Niles is not happy about. On the plus side, Donny has managed to secure something for him out of the divorce settlement: Maris' lake-front cottage, Shady Glen.

If I confess my love for Daphne to Roz, can I 'pretend' to also be in love with her so we can go on a romantic weekend getaway together?

Burn Notice (rw with L) 1x01 Pilot

Michael Westen, a contract agent for various agencies including the CIA, finds that a burn notice has been issued for him. Stranded in Miami, he takes the case of a caretaker accused of stealing millions from his boss.

Detective Bautista vs. The Devil. Featuring: a yogurt-enthusiast/ burned spy, his hypochondriac mother, his explosive once-Irish ex-girlfriend, and their roguish sugar-mommy-loving bestie.

#ugly betty#frasier#burn notice#polls#tumblr polls#jess watches#day 349#nothing new was appealing so i went back to a past favourite#how did burn notice start in 2007??

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abigail O'Neill

Birth Name: Abigail Elizabeth O'Neill

Born 15 May 1997

Country of origin: USA

Currently Residing In: USA

Height: 5' 6"

Relationship Status: Single

Playboy Playmate of the Month for May 2019. Abby was born in Wichita, Kansas in 1997 and graduated Southeast High School in 2015. She says she did one semester at University of Kansas at Lawrence and then transferred to Seattle University in Washington, as she wanted to do fitness modeling and so many of the fitness brands are headquartered in the northwest. Abby is represented by Wilhelmina – Miami.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

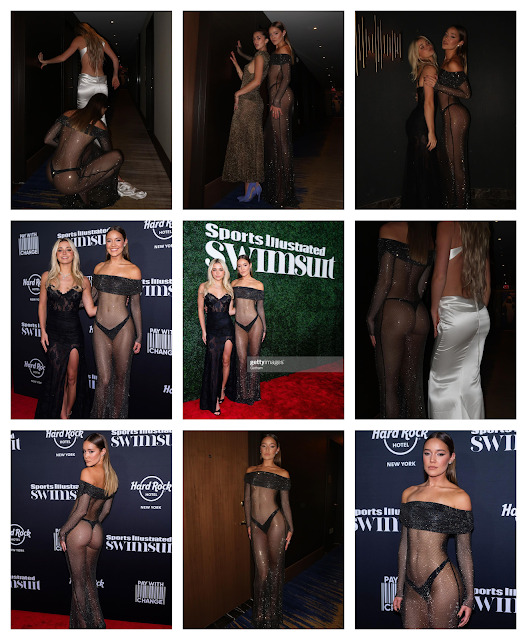

Rising Instagram Star Olivia Ponton Takes the Fashion World by Storm at Victoria's Secret Show

In the glitzy and glamorous world of Instagram modeling, one name that has been making waves is Olivia Ponton. The 21-year-old sensation from Florida has captivated hearts and lenses alike with her stunning presence and charismatic figure. Olivia Ponton's recent appearance at the Victoria's Secret fashion show turned heads, leaving everyone in awe of her cheeky and confident look.

A Star in the Making

Born on May 30, 2002, Olivia Ponton is a young star who has risen to prominence at an astonishing pace. As a Gemini, she embodies the free-spirited and fun-loving nature often associated with her zodiac sign. Olivia hails from a modest family in Florida and continues to reside in sunny Miami with her loved ones. While she occasionally shares glimpses of her family life on social media, Olivia has chosen to keep her parents' identities private. She also remains tight-lipped about any potential siblings.

Olivia's educational journey led her through Naples High School, where she completed her high school education. However, she has not pursued higher education at a college or university, as her modeling career skyrocketed.

Modeling Success and Wealth

Olivia Ponton's net worth has reached an impressive $1 million by 2023. While she earns a significant portion of her income from brand endorsements and paid collaborations, her modeling projects and sponsored advertisements remain her primary sources of wealth. She officially signed with the prestigious Wilhelmina Modeling Agency, a testament to her talent and potential in the modeling world.

Her Instagram account, under the username 'olivia ponton,' boasts over 900 thousand devoted followers. Here, she shares behind-the-scenes glimpses of her shoots and offers insights into her personal life. Olivia is revered by her fans not only for her style inspiration but also for her dedication to fitness. Her workout routine, especially her abs workouts, garners attention on TikTok, where she boasts over 3 million followers. Many of her fans attest to the effectiveness of her fitness tips. Olivia has recently expanded her online presence to YouTube, where she shares workout routines, vlogs, and informative fitness videos.

A Stunning Figure and Love Life

Olivia Ponton's stunning 5 feet 8 inches frame and 56 kg weight have contributed significantly to her popularity as a rising model. Her body measurements (32-24-36) are enviable, and her blonde hair and brown eyes add to her allure. Olivia's dedication to maintaining her health through daily workouts is evident, making her a perfect fit for the modeling world.

In matters of the heart, Olivia is currently in a relationship with Kio Cyr, and the couple has been together since February 2020. Their love is no secret, as they openly share their affection on social media platforms and occasionally post pictures together. While Olivia is yet to tie the knot or become a mother, her career is in full swing, and she continues to gain fans and recognition in her field.

As Olivia Ponton blazes her trail in the fashion and modeling industry, it's clear that this Instagram sensation from Florida is on a meteoric rise to stardom. Her confidence, talent, and dedication have taken her from a small-town girl to a global sensation, and there's no doubt that we'll be seeing more of Olivia Ponton in the years to come.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fountainebleau Miami Beach by WALLY IV

Director & Photographer: Wally IV

Model: Francisco Escobar

Agency: Wilhelmina

edited using my presets

1 note

·

View note

Text

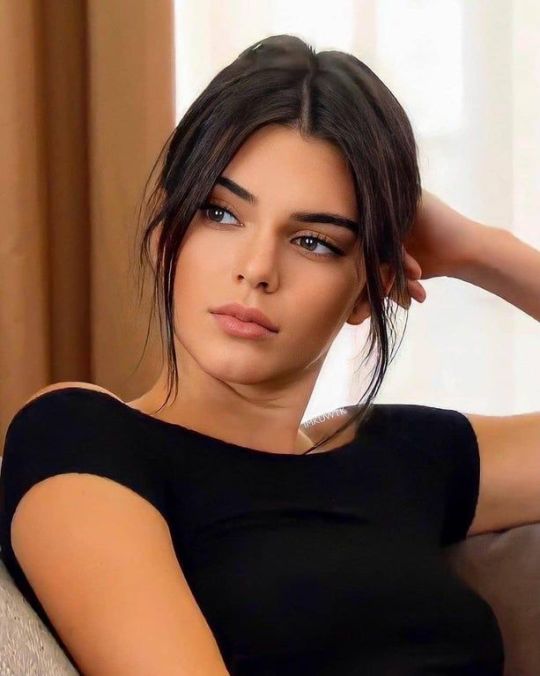

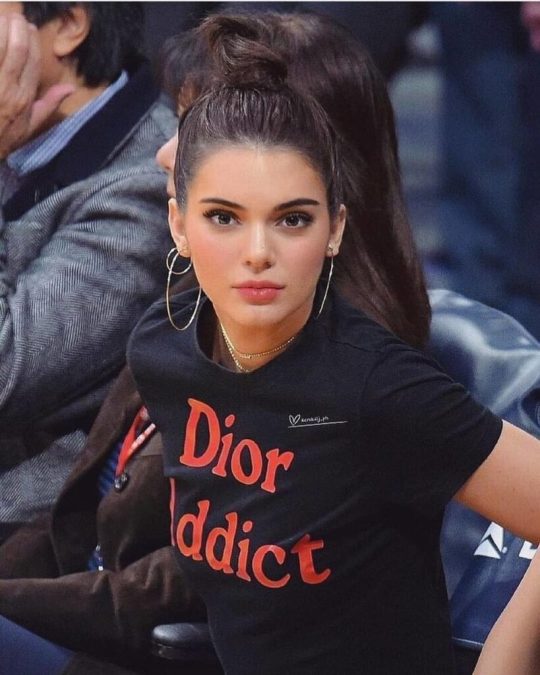

Kendall Jenner, American Model, Reality TV Star & Business Women with Luxury life as end of 2023

"Kendall Jenner, American model, reality TV star, and businesswoman, enjoys a luxurious life as of the end of 2023." Kendall Jenner, American Model, Reality TV Star & Business Women with Estimated Net worth of $60 million Kendall Jenner has been up to in recent days: - She was spotted attending the 2023 Met Gala in New York City on May 2. She wore a custom Off-White gown by Virgil Abloh. - She was the new face of L'Oreal Paris in June 2023. She starred in a campaign for the brand's new lipstick line. - She was seen spending time with her rumored boyfriend, Bad Bunny, in July 2023. They were spotted out together in Los Angeles and Miami.

Kendall jenner - She announced that she is launching her own tequila brand, 818 Tequila, in August 2023. The brand is named after the area code of her hometown, Calabasas, California. - She has been active on her Instagram account in recent days, sharing photos of her travels, modeling work, and time with friends and family. Kendall Jenner is a very private person, so it is not always known what she is up to. However, it seems that she is keeping busy with her modeling career, her new tequila brand, and her relationship with Bad Bunny. Kendall Jenner Early Life. Kendall Jenner Reality Star Kendall Jenner and Bad Bunny Kylie Cosmetics Kendall Jenner Followers on Social Media Kendall Jenner Modeling Career Kendall Jenner business woman Kendall Jenner Connection With Brands Kendall Jenner Net worth In 2023 Kendall Jenner Viral Fashion Videos Kendall Jenner is currently 27 years old and is still a supermodel. She made her runway debut in 2011 and has since walked for some of the most prestigious fashion houses in the world, including Chanel, Dior, and Versace. She has also appeared on the covers of countless magazines, including Vogue, Elle, and Harper's Bazaar. In 2017, Jenner was named the world's highest-paid model by Forbes, with an estimated annual income of $22.5 million. She has since stepped back from the runway somewhat, but she is still one of the most in-demand models in the world. In addition to her modeling career, Jenner is also a reality TV star. She has appeared on her family's reality show Keeping Up With the Kardashians since 2007. In 2022, the show was rebooted as The Kardashians on Hulu. Jenner is also a businesswoman. She has her own clothing line, Kendall + Kylie, which she co-founded with her sister Kylie Jenner. She also has her own tequila brand, 818 Tequila. Jenner is currently dating Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny. The couple have been linked since early 2023. Here are some of the things Kendall Jenner is currently working on: - She is filming the second season of The Kardashians. - She is working on her tequila brand, 818 Tequila. - She is developing her clothing line, Kendall + Kylie. - She is dating Bad Bunny. Kendall Jenner is a successful supermodel, reality TV star, and businesswoman. She is constantly working on new projects and is always looking for ways to expand her empire. She is an inspiration to many young women and is sure to continue to be a force in the entertainment industry for many years to come.

Kendall Jenner Early Life.

Kendall jenner Kendall Nicole Jenner was born on November 3, 1995, in Los Angeles, California. She is the daughter of Kris Jenner and Caitlyn Jenner (formerly Bruce Jenner), and is the half-sister of Kourtney, Kim, Khloé, and Rob Kardashian, as well as Kylie Jenner. Jenner began modeling at a young age, appearing in campaigns for Sears, Forever 21, and The Gap. She made her runway debut in 2011 at Sherri Hill's New York Fashion Week show. In 2012, she signed with Wilhelmina Models and began walking in shows for top designers such as Marc Jacobs, Chanel, and Dior. Jenner has also appeared on the covers of numerous magazines, including Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, and Elle. She has her own clothing line, Kendall + Kylie, which she designs with her sister Kylie. In 2015, Jenner was named one of the highest-paid models in the world by Forbes magazine. She has also won several awards for her modeling work, including the Model of the Year award at the British Fashion Awards in 2016. Jenner is also a reality TV star. She has appeared on Keeping Up With the Kardashians since 2007. She has also starred in her own reality show, Kendall's World, which aired on E! in 2017. Jenner is a successful model and reality TV star. She is also a businesswoman, with her own clothing line and endorsement deals. She is one of the most popular celebrities in the world, and her influence on fashion and culture is undeniable.

Kendall Jenner Reality Star

Kendall jenner Kendall Jenner is a reality TV star and model. She rose to fame in 2007 on the reality television show Keeping Up with the Kardashians, in which she starred for 20 seasons and nearly 15 years from 2007 to 2021. The success of the show led to the creation of multiple spin-off series including Kourtney and Khloe Take Miami (2009), Kourtney and Kim Take New York (2011), Khloe & Lamar (2011), Rob & Chyna (2016) and Life of Kylie (2017). Jenner began modeling at the age of 14. After working in commercial print ad campaigns and photoshoots, she had breakout seasons in 2014 and 2015, walking the runways for high-fashion designers during the New York, Milan, and Paris fashion weeks. She has since appeared on the cover of several international Vogue editions and Harper's Bazaar, as well as walked for Victoria's Secret and acted as a brand ambassador for Estée Lauder's multimedia ad campaigns. Jenner is one of the world's highest-paid supermodels, and has been ranked as the highest-paid model in the world by Forbes in 2017 and 2018. She has also been praised for her body positivity and for using her platform to promote diversity in the fashion industry. In addition to her modeling career, Jenner is also a businesswoman. She has her own clothing line, Kendall + Kylie, with her younger sister Kylie Jenner. She has also launched her own fragrance line, Kendall Jenner Signature. Jenner is a popular figure on social media, with over 294 million followers on Instagram. She is often seen as a fashion icon and role model for young women. Here are some of the reasons why Kendall Jenner is famous: - She is a member of the Kardashian-Jenner family, one of the most famous families in the world. - She is a successful model who has appeared on the covers of magazines and walked the runways for major fashion brands. - She is a social media influencer with over 294 million followers on Instagram. - She is a businesswoman with her own clothing line and fragrance line. - She is known for her body positivity and for using her platform to promote diversity in the fashion industry.

Kendall Jenner and Bad Bunny

Kendall Jenner and Bad Bunny were first spotted together in February 2023, and they have been seen together several times since then. They have attended Coachella together, gone on double dates with friends, and been seen out and about in Los Angeles. There is no confirmation that they are officially dating, but they seem to be very close. A source told People magazine in February that Kendall and Bad Bunny are "spending time together" and that "Kendall recently started hanging out with him." Another source told Entertainment Tonight in July that the couple is "getting closer" and that they have "a ton of chemistry." Only time will tell if Kendall Jenner and Bad Bunny are officially a couple, but they are definitely enjoying each other's company.

Kendall Jenner's Kylie Cosmetics

Kendall jenner Kylie Cosmetics is an American cosmetics company founded by Kylie Jenner in 2014. The company began selling Kylie Lip Kits, a liquid lipstick and lip liner set, on November 30, 2015. Formerly known as Kylie Lip Kits, the company was renamed Kylie Cosmetics in 2016. Kylie Cosmetics is known for its high-quality products, trendy colors, and affordable prices. The company has been very successful, and Kylie Jenner is now one of the youngest self-made billionaires in the world. Some of the most popular products from Kylie Cosmetics include: - Lip Kits - Kyliners - Concealer - Eye Shadow Palettes - Bronzers - Contour Kits *Highlighters - Setting Powders - Lip Glosses - Face Masks Kylie Cosmetics products are available online and at select retailers. Here are some of the reasons why Kylie Cosmetics is so famous: - Kylie Jenner is a popular reality TV star and social media influencer. - The company's products are high-quality and affordable. - The company often releases limited-edition products that sell out quickly. - Kylie Cosmetics has a strong social media presence, with over 300 million followers on Instagram. If you are looking for high-quality, affordable cosmetics, Kylie Cosmetics is a great option. The company has a wide variety of products to choose from, and its products are consistently rated highly by customers.

Kendall Jenner Followers on Social Media

Source Google Kendall Jenner is active on the following social media platforms: - Instagram: @kendalljenner (294 million followers) - Twitter: @KendallJenner (37.8 million followers) - Facebook: @KendallJenner (43.4 million followers) - TikTok: @kendalljenner (33.2 million followers) - YouTube: KendallJenner (3.52 million subscribers) She does not have a verified account on Snapchat. Here are the number of followers she has on each platform as of August 17, 2023: - Instagram: 294 million - Twitter: 37.8 million - Facebook: 43.4 million - TikTok: 33.2 million - YouTube: 3.52 million Kendall Jenner is the most-followed model on Instagram and the 13th most-followed person overall. She is also the most-followed person on Twitter among models. Kendall Jenner's Instagram account is @kendalljenner. She has over 293 million followers and 638 posts. Her latest post is a photo of her with Bad Bunny at Drake's concert. Here are some of the things you can find on her Instagram: - Modeling photos from her various campaigns. - Photos with her family and friends. - Behind-the-scenes photos from her work. - Travel photos. - Outfits of the day. - Selfies. Kendall Jenner is one of the most popular models in the world, and her Instagram account is a great way to see her latest work and get a glimpse into her life.

Kendall Jenner Modeling Career

Kendall jenner - Kendall Jenner walking the runway for Marc Jacobs at New York Fashion Week in 2014. - Kendall Jenner posing for a campaign for Calvin Klein in 2015. - Kendall Jenner on the cover of Vogue Paris in 2017. - Kendall Jenner posing for a campaign for Estee Lauder in 2018. - Kendall Jenner walking the runway for Versace at Milan Fashion Week in 2022. Kendall Jenner has modeled for some of the biggest fashion brands in the world, including Chanel, Dior, Balmain, and Versace. She has also appeared on the covers of many magazines, including Vogue, Vanity Fair, and Harper's Bazaar. She is considered to be one of the most successful models in the world. In addition to her modeling career, Kendall Jenner is also a businesswoman. She has her own clothing line and her own tequila brand. She is also a co-founder of the 818 Tequila brand. Kendall Jenner is a global icon and a role model for many young women. She is known for her beauty, her style, and her entrepreneurial spirit.

Kendall Jenner business woman

Kendall jenner Kendall Jenner is a successful model, reality TV star, and businesswoman. She has a net worth of $45 million and is one of the highest-paid models in the world. Jenner's business career began in 2009, when she was signed to Wilhelmina Models. She quickly rose to fame and began modeling for some of the biggest fashion brands in the world, including Chanel, Dior, and Balmain. In 2017, she was named the world's highest-paid model by Forbes. In addition to modeling, Jenner has also pursued a number of other business ventures. She has her own clothing line, Kendall + Kylie, which she designs with her younger sister, Kylie Jenner. She also has her own fragrance line, Kendall Jenner Signature. In 2021, she launched her own tequila brand, 818 Tequila. Jenner is also a successful businesswoman in the digital space. She has over 200 million followers on Instagram, and she uses her platform to promote her businesses and products. She also has her own mobile app, Kendall Jenner Official. Jenner is a savvy businesswoman who has successfully leveraged her fame and platform to create a successful business career. She is an inspiration to young women everywhere who dream of pursuing a career in fashion or business. Here are some of the business ventures that Kendall Jenner has been involved in: - Modeling: Jenner has been modeling since she was a teenager and has worked with some of the biggest fashion brands in the world. She is one of the highest-paid models in the world. - Clothing line: Jenner has a clothing line with her younger sister, Kylie Jenner, called Kendall + Kylie. The line is sold at retailers like PacSun and Topshop. - Fragrance line: Jenner has her own fragrance line called Kendall Jenner Signature. The line includes perfumes, body mists, and lotions. - Tequila brand: Jenner launched her own tequila brand, 818 Tequila, in 2021. The tequila is made from 100% blue agave and is produced in Jalisco, Mexico. - Mobile app: Jenner has her own mobile app called Kendall Jenner Official. The app features exclusive content from Jenner, including photos, videos, and behind-the-scenes looks at her life. - Endorsement deals: Jenner has endorsement deals with a number of brands, including Adidas, Calvin Klein, and Pepsi. She is one of the most sought-after endorsers in the world. Jenner is a successful businesswoman who has built a successful career in a variety of industries. She is an inspiration to young women everywhere who dream of pursuing a career in fashion, business, or entrepreneurship.

Kendall Jenner Connection With Brands

Kendall jenner Kendall Jenner has her own tequila brand called 818 Tequila. It is a small-batch tequila made from 100% Blue Weber agave grown in Jalisco, Mexico. The tequila is aged for 12 to 18 months in oak barrels. 818 Tequila is available in three expressions: Blanco, Reposado, and Añejo. In addition to her own brand, Kendall Jenner has also endorsed a number of other brands, including: - Adidas - Estée Lauder - Fendi - Longchamp - Proactiv - Stuart Weitzman - Pepsi - Kylie Cosmetics - Moon She has also walked the runway for many high-fashion brands, including Chanel, Dior, Versace, and Marc Jacobs. Kendall Jenner is one of the most popular and in-demand models in the world. She has a net worth of over $45 million.

Kendall Jenner Net worth In 2023

Kendall jenner As of 2023, Kendall Jenner's net worth is estimated to be $60 million. She is the second richest Kardashian-Jenner sister, after Kylie Jenner. Her wealth comes from her modeling career, her family's reality TV show, Keeping Up with the Kardashians, and her various endorsement deals. In 2018, Kendall Jenner was the highest-paid model in the world, with earnings of $22 million. She has since signed endorsement deals with a number of high-profile brands, including Adidas, Estée Lauder, and Pepsi. She has also launched her own tequila brand, 818 Tequila. Kendall Jenner is one of the most popular and in-demand models in the world. She has over 278 million followers on Instagram, making her one of the most followed people on the platform. Her social media presence has helped her to generate significant revenue from endorsement deals. Kendall Jenner is a successful businesswoman who has built a diversified portfolio of assets. She is likely to continue to grow her wealth in the years to come.

Kendall Jenner Viral Fashion Videos

Read the full article

#adiadas#ashion#Fashion#million#Money#new#she#Social#StarAchievement#StarActing#StarAppearances#StarAwardsNight#StarEvents#StarFilm#StarGlam#StarIndustry#StarInspiration#StarMotivation#StarPerformance#StarRecognition#StarRole#StarShowbiz#StarSpotlight#StarStage#StarSuccessStory#StarTalentShow#StarTrends#StarTVShow#World

1 note

·

View note

Text

By Safiya Sinclair

The first time I left Jamaica, I was seventeen. I’d graduated from high school two years before, and while trying to get myself to college I’d been scouted as a model. And so I found myself at the Wilhelmina Models office in Miami, surrounded by South Beach’s finest glass windows with all my glass hopes, face to face with a famous one-named model who was now in her sixties. When her gaze halted at my dreadlocks, I shouldn’t have been surprised at what came next.

“Can you cut the dreads?” she asked, as she flipped through my portfolio, her soft accent blunting the impact of the words.

Back home in Kingston, hair stylists would leave my dreadlocks untouched, tied up in a ponytail with my good black ribbon, deciding that the problem of my hair was insolvable.

“Sorry,” I said. “My father won’t allow me.”

She glanced over at the agent who had brought me in.

“It’s her religion,” he explained. “Her father is Rastafarian. Very strict.”

The road between my father and me was woven in my hair, long spools of dreadlocks tethering me to him, across time, across space. Everywhere I went, I wore his mark, a sign to the bredren in his Rastafari circle that he had his house under control. Once, when I was feeling brave, I had asked my father why he chose Rastafari for himself, for us. “I and I don’t choose Rasta,” he told me, using the plural “I” because Jah’s spirit is always with a Rasta bredren. “I and I was born Rasta.” I turned his reply over in my mouth like a coin.

My father, Djani, had also been seventeen when he took his first trip out of Jamaica. He travelled to New York in the winter of 1979 to find his fortune. It was there, in the city’s public libraries, that my father first read the speeches of Haile Selassie and learned about the history of the Rastafari movement. In the early nineteen-thirties, the street preacher Leonard Percival Howell heeded what is known as the Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey’s call to “look to Africa for the crowning of a Black king,” who would herald Black liberation. Howell discovered Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia, the only African nation never to be colonized, and declared that God had been reincarnated. Inspired by Haile Selassie’s reign, the movement hardened around a militant belief in Black independence, a dream that would be realized only by breaking the shackles of colonization.

As he read, my father became aware of the racist downpression of the Black man happening in America. He understood then what Rastas had been saying all along, that systemic injustice across the world flowed from one huge, interconnected, and malevolent source, the rotting heart of all iniquity: what the Rastafari call Babylon. Babylon was the government that had outlawed them, the police that had pummelled them, the church that had damned them to hellfire. Babylon was the sinister and violent forces born of western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people. It was the threat of destruction that crept even now toward every Rasta family.

Just as a tree knows how to bear fruit, my father would say, he knew then what he needed to do. On a cold day in February, his eighteenth birthday, my father stood before a mirror in New York City and began twisting his Afro into dreadlocks, the sacred marker of Rastafari livity, a holy expression of righteousness and his belief in Jah. When he returned to Jamaica, his mother took one look at his hair and refused to let him into the house. It was shameful to have a Rasta son, she said. My father, with nowhere else to go, reluctantly cut his hair back down to an Afro.

Soon my father began spending time around a drum circle with Rasta elders in Montego Bay, sitting in on the spiritual and philosophical discussions that Rastas call reasoning. “Rasta is not a religion,” my father always said. “Rasta is a calling. A way of life.” There is no united doctrine, no holy book of Rastafari principles. There is only the wisdom passed down from elder Rasta bredren, the teachings of reggae songs from conscious Rasta musicians, and the radical Pan-Africanism of revolutionaries like Garvey and Malcolm X. My father felt called to a branch known as the Mansion of Nyabinghi, the strictest and most radical sect of Rastafari. Its unbending tenets taught him what to eat, how to live, and how to fortify his mind against Babylon’s “ism and schism”—colonialism, racism, capitalism, and all the other evil systems of western ideology that sought to destroy the Black man. “Fire bun Babylon!” the Rasta bredren chanted every night, and the words took root in him. He was ready to decimate any heathen who stood in his way.

Hanging on the mint-green living-room wall of our family’s house in Bogue Heights, a hillside community overlooking Montego Bay, was a portrait of Haile Selassie, gilded and sceptered at his coronation, his eyes as black as meteorites. It was flanked by a poster of Bob Marley and a photograph of my father, both onstage, both throwing their dreadlocks like live wires into the air.

Every morning of my childhood began the same way, with the dizzying smell of ganja slowly pulling me awake. My mother, Esther, who had first embraced the Rastafari way of life when she met my father at nineteen, was always up before dawn, communing with the crickets, busying herself with housework and yard work. Whenever she worked, she smoked marijuana. The scent of it clung to her long auburn dreadlocks. She carried a golden packet of rolling paper on her at all times, stamped with a drawing of the Lion of Judah waving the Ethiopian flag, the adopted symbol of the Rastafari. My brother, Lij, my sister, Ife, and I pawed and pulled at her, but she did not mind. If she was with us, she was ours.

My father was the lead singer in a reggae band called Djani and the Public Works. When I was seven, Lij five, and Ife three, he met some Japanese record-label executives at the hotel where the band performed nightly, and they agreed to fly the musicians to Tokyo to play reggae shows. They stayed for six months and recorded their first album. After he left, my mother cleared our back yard and planted some crops, which soon became towering stalks of sugarcane, a roving pumpkin patch, and vines and vines of gungo peas, all exploding outward in swaths of green. We had always kept to an Ital diet: no meat, no fish, no eggs, no dairy, no salt, no sugar, no black pepper, no MSG, no processed substances. Our bodies were Jah’s temple.

Early on school mornings, under the watchful eye of the holy trinity, my mother combed my black thundercloud of hair, often with me tearfully begging her to stop. Once, the children at my grandmother’s Seventh-day Adventist church had asked me why I didn’t have dreadlocks like my parents; I remembered the certainty in my grandma’s voice when she said that we would be able to choose how to wear our hair.

Even though the combing was painful, I still wouldn’t have chosen dreadlocks. When my mother was finished, I swung my glistening plaits, fitted with blue clips to match my school uniform, back and forth, back and forth, pink with delight. I felt it was all worth it then. My mother made it look easy, corralling three children by herself to school every morning while my father was away.

Babylon came for us eventually, even in our kingdom of god-sent green. One Sunday during our Christmas break, my mother dragged a comb across my head and gasped. Two large fistfuls of hair were stuck in its teeth, yanked loose like weak weeds from dirt. I screamed.

“Oh, Jah. Oh, Jah. Oh, Jah,” she said, holding me as I cried, blocking my hand from trying to touch my scalp, where I now had a bald spot. Ife was fine, but Lij’s hair was also falling out in clumps. My father distrusted Babylon’s doctors. My mother did, too—until she had children.

We had been infected with barber disease, the doctor told us, a kind of ringworm spread first by barbers’ tools, then by children touching heads at school. Babylon’s disease. Mom closed her eyes as she listened. The doctor prescribed a thick antifungal cream and a chemical shampoo.

A week later, despite the treatment, there was scant improvement. My mother gathered up all the combs in the house and flung them into a trash bag, along with the medicine. Hair for the Rastafari signified strength. My father called his hair a crown, his locks a mane, his beard a precept. What grew from our heads was supposed to be most holy. My mother took our blighted scalps as a moral failure, ashamed that we had fallen to Babylon’s ruin so soon after my father had gone.

For the rest of the break, she tended to our heads with a homemade tincture. After a few days, my hair started growing back. “Praise Jah,” Mom said, as she began the process of twisting all our hair into dreadlocks. Day after day, we sat, snug between her legs, as she lathered our heads in aloe-vera gel and warm olive oil.

Within a few weeks, my hair had stiffened and matted into sprouts of thick antennae, bursting from my head. There was no turning back now. From that point on, combing and brushing our hair was forbidden, on a growing list of NO.

When my siblings and I returned to our primary school after the break, the students gawked at us as if we were a trio of aliens disembarking from a spaceship. They crowded around, trying to sniff or pull at our locks. If they could have dissected us alive, I think they would have.

Not long after, a sixth grader began shadowing me. She crept up close while singing in my ear, “Lice is killing the Rasta, lice is killing the Rasta,” a widespread taunt in the nineties, which co-opted the tune of a popular reggae song.

My cheeks stung in humiliation. For the first time, I felt ashamed to be myself. At lunchtime, I told my brother about the girl, her needling insult. My brother shook his head and kissed his teeth the way grownups did.

“Saf, don’t pay her no mind. All ah dem a duppy,” he said. “And we are the duppy conquerors.” He was trying to sound like a big man, talking like our father.

I tried to imagine what my father would say. He always told me to be polite but right. “I man and your mother didn’t birth no weakheart,” he said. “Always stand up for what you know is right. You overstand?” Even from afar, his mind moved mine like a backgammon piece.

I decided to go to the teachers’ lounge and tell my third-grade teacher about the girl’s teasing. Tapping me gently on the shoulder, she told me that with my good grades I should pay such things no mind.

As I walked away, still pensive, I heard her and some of the other teachers talking.

“But it’s a shame, innuh,” a new teacher’s voice chimed in. “I really thought the parents were going to give them the choice.”

We were under our favorite mango tree by the front gate when a car rolled up one day in early May. Suddenly, my father appeared like the sun, beeping the horn and flashing his perfect teeth at the sight of us. We jumped on him, and cried; the fireworks of feelings had nowhere else to go. He brought in a parade of bags and boxes from Japan, a brand-new electric Fender guitar slung across his back. He was buoyant. All afternoon, he kept touching his fingers to our dreadlocks. We could tell he was pleased.

Inside the house, he unzipped his suitcases and showered us with mounds of stuffed toys, exquisite notebooks, new clothes and shoes, and a Nintendo Game Boy with Japanese cartridges. For Mom, he brought fancy lotions, a robe, and packets of something called miso. We cheered at every new gift. My father was our Santa, if Rasta believed in Babylon’s fables.

Dad was home with us that entire summer. Every day, he was a more carefree version of himself. He taught us to play cricket, told us the same ten jokes of his childhood, and dazzled us with his tree-climbing skills. His recording contract was for two years, but the record label could obtain only six-month visas for the band at a time. Once school began, he went back to Japan to finish the album. We didn’t have a phone, so we visited the shop of his closest bredren, Ika Tafara, to call him every weekend.

By the time we walked into Ika’s shop for the Kwanzaa celebration that December, I felt like I belonged. About thirty Rasta bredren and their families had come from all over Mobay to gather and give thanks. We recited Marcus Garvey’s words like scripture. I played the conga drum and sang of Black upliftment with other Rasta children. There were about twenty of us there, peeking from behind our mothers’ hems. And though he was across the sea, my father felt present, the sound of his voice ringing out through the store’s speakers.

But when my father got back the second time, the following May, he seemed different. His relationship with one of his bandmates had imploded, taking the band’s hopes with it, and he was once again playing reggae for tourists at the hotels lining the coast. My sister Shari was born a month after his return. With the birth of another Sinclair daughter, my father’s control over us tightened. One afternoon, he decided that my siblings and I needed to be purified. I watched him stalk through the yard, pulling up cerasee leaves, bitter roots, and black vines, which my mother blended into a pungent goop and poured into three big glasses. He loomed over us for what seemed like hours, as we bawled and retched, struggling to swallow the foul potion. We were there until night fell, until my father believed we had finally been cleansed.

“The I them have to be vigilant,” he said when it was over. Our joy had made us heedless, easy prey for the wicked world. We would no longer be allowed to run around outside, or even to leave the yard. “Chicken merry, hawk deh near,” he reminded us.

“I man don’t want my daughters dressing like no Jezebel,” he told my mother later. At his instruction, she threw out every pair of pants and shorts my sisters and I owned. Now we would wear only skirts and dresses made from kente cloth, as our mother did. Our hems were to fall below our knees, our chest and midriff to be covered at all times. Pierced ears, jewelry, and makeup—all those garish trappings of Babylon—were forbidden. “And once you reach the right age,” my father said, “the I will wrap your locks in a tie-head like your mother.” I realized I had been naïve, in not expecting that this was the life my father had imagined for me.

My hair hadn’t been brushed in two years. Flecks of lint and old matter knotted down the length of each dreadlock, a nest containing every place I had laid my head. Dad caught me pushing my fingers through the thicket of roots in the bathroom mirror once, as I tried to twist the crown of my hair into shape.

“Stop that,” he said. “Hair fi grow. Naturally and natural only. Like Jah intended.”

“Yes, Daddy,” I said.

With each month came a new revocation, a new rule. Soon he didn’t even allow us around other Rastafari people. He trusted no one, not even them, with our livity. In our household rose a new gospel, a new church, a new Sinclair sect. The Mansion of Djani.

Whenever our father was out of the house, which was almost nightly, my siblings and I resumed our outdoor play. One day, a few weeks later, Lij chased me across the lawn. I zipped left and ran sideways into the house to lose him. But there he was again. Laughing, I turned to face him, and his running motion drove the full force of his body into my jaw, which slammed hard against the bathroom wall. I felt my front tooth crumble to chalk in my mouth. I slid my tongue across my gums and found a sharp crag in the place where my tooth used to be, and sobbed.

My parents couldn’t afford to fix my tooth. They didn’t have insurance, and a dentist friend told them it didn’t make sense to get it capped until I was older anyway, because my mouth was still growing. I wanted to protest, but I knew my father thought that my distress over my tooth was only vanity, and vanity was a mark of Babylon. I suspect he liked me this way. My mouth was now a barricade between me and the onslaught of adolescence, a broke-glass fence around my body.

I stopped smiling. At school, I sat clench-mouthed and held my hand across my mouth whenever I spoke.

At the end of the school year, there was a carnival. Venders came with cotton candy and peanut brittle and their bright pandemonium of wares. One of the attractions was a mule ride, and after some begging my mother said Ife and I could do it. I pulled my hand-sewn dress over my knees and got on the mule sidesaddle. As we were led around the parking lot by the animal’s owner, a photographer appeared and snapped our picture; I made sure to shut my mouth tight. The next day, the local newspaper printed the photo in a half-page spread, my face gloomy above the caption “Two Rasta girls riding a mule.”

One morning, when I was nearing the end of sixth grade, my mother held up the classifieds in excitement. “Look at this, Djani,” she said. There was an ad announcing two scholarships for “gifted and underprivileged” students to attend a new private high school called St. James College, in Montego Bay. For my parents, this would mean tuition paid, uniforms made, one less child to worry about. A burden lifted. Students had to apply, and a chosen few would then be interviewed by the school’s founders.

I pushed out my lips. “So does this mean that if I want to go to any school in my life, I’m always going to have to get a scholarship?” I asked. I knew, as every Jamaican child knows, that no sentence directed to your parents should begin with the word “So.”

“Have to get a scholarship? You think I and I made ah money?” my father said. “Gyal, get outta my sight.” I hid in the bedroom for the rest of the day and wept. My father used only regal honorifics for the women in his life. Empress. Princess. Dawta. The word “gyal” was an insult in Rasta vernacular. It was never used for a girl or a woman who was loved and respected. For weeks, the word taunted me, my girlhood a stain I could not wash out.

We applied, and when my mother told me I was one of the finalists I was not surprised. I had alchemized my father’s rage into a resolve to be so excellent that my parents would never have to worry again.

My mother and I went to an office building downtown for the interview. We were met by a short white woman wearing round glasses who introduced herself as Mrs. Newnham. She asked me to come with her, and I followed. I looked back and saw my mother raise a confident fist in my direction.

Five men, most of them white, sat at a table in the center of a large, cold room. They all wore gold watches and school rings with large ruby insignias on them. I had never been alone with so many white people before. The men greeted me. One white man asked what I did in my spare time.

I told them I loved to read and write poetry, and that my favorite poem was “The Tyger,” by William Blake. Before they could ask another question, I began to recite it. I looked at each of them as I spoke. The words gave me electric power.

“My God, you speak so well,” another white man said. “You speak so well,” they all repeated. I was unsure how else I was supposed to speak.

The kindest white man at the table, who had a long nose and blue eyes, asked me to tell him about something in the news. I stopped to think. I knew that everybody had been talking about the West Indian cricketer Brian Lara’s triumphant summer and that would be the most expected answer.

“I’ve been following the Donald Panton scandal,” I said. Two of the men looked up at me in surprise. Donald Panton was the other big story that summer—a prominent Kingston businessman who had been under investigation for financial fraud. (Panton was eventually cleared.) Here was my audience, I thought.

When the interview was over, the committee came out with me, congratulating my mother and asking her what her secret was to raising children. “If I had a dime for every time somebody asked me that,” my mother said, laughing, “I would be rich.”

Before we even left the building, Mrs. Newnham told us that I had been awarded a scholarship to St. James College. My mother hugged me, and thanked Mrs. Newnham and the committee. Outside the building, she jumped and squealed.

“Donald Panton?” my mother said. “What do you even know about that, Safiya?”

“Everything,” I said.

There were eight girls in my class, two of us scholarship students. The others were mostly white Jamaicans and children of American and Canadian expats, chirpy girls whose toy-blond mothers picked them up every evening by car. These girls had all gone to the same private prep school together, had all played tennis and lunched at the yacht club together, and, when it was time for high school, their parents had built them a private school. The bond between them was as unspoken and unbreakable as the barrier between us.

One morning, I arrived at school early enough to wander around in the back yard. Suddenly, the quiet was broken by the science teacher, whom I’ll call Mrs. Pinnock, beckoning me up to a terrace on the second floor.

“Sinclair, why were you down there?” she said. “You should not be wandering around the school grounds alone before the teachers arrive.”

I concentrated on her shoes as she spoke; she wore the ubiquitous sheer nylons and polished block heels of Jamaican teachers.

“And can you please brush your . . . hair?” she added, her voice sharpening. “You can’t be just walking around here looking like a mop.” I would not let her see me react.

“Miss, my father says I am not allowed to brush my hair,” I said, trying to sweep my locks away from my face and off my head forever.

Mrs. Pinnock suddenly took hold of my wrist.

“What’s this?”

There were deep-brown, intricately laced henna patterns across my hands. I explained that a family friend had stained my hands and feet with her homemade henna.

She reminded me that tattoos weren’t allowed.

“It’s not a tattoo, Miss,” I said, my voice quivering now.

“Then go to the bathroom and wash it off, ” she said, articulating each word slowly.

In the bathroom, I scrubbed my hands raw, then walked back to the teachers’ lounge, where I showed Mrs. Pinnock that the dye truly didn’t come off so easily.

“You see this?” she said, gesturing to the other teachers in the room. “Now these people just taking all kind of liberties.” There was no mistaking whom she meant.

At morning assembly, she announced that any student seen with any kind of tattoo at school would get detention or suspension.

During lunchtime, the rich girls often skipped the cafeteria and ate under the shade of the trees in the front yard. The rest of us would follow them out into the noonday sun. Many girls would buy beef patties and warm coco bread from a tiny tuckshop on the premises—all food that I was forbidden. My cheap nylon lunch bag held a sweaty lettuce-and-cheese sandwich, a peeled orange, and a bag of off-brand chips my mom had bought from a Chinese grocery store.

That day, a classmate whom I’ll call Shannon decided to climb a young mango tree. I watched her as she clambered up onto the lowest branch, her pleated skirt ballooning and exposing her legs.

“I think it’s cool, by the way,” Shannon called out to me from above. “I always wanted to try henna. Teachers here are such prudes.”

“Thanks,” I said.

Shannon leaned down from her perch, her gaze fixed on my locks, and asked me if henna was part of my religion. I shook my head no. Then she asked if I could wear nail polish. The answer was no, it was always no. But she kept going, as if she were trying to reveal something clever about Rastafari to me. Why can’t you pierce your ears? Who made the rules?

My father, I wanted to tell her. But how could I convey that every Rastaman was the godhead in his household, that every word my father spoke was gospel?

I leaned back against the trunk of the tree, smoothing down my skirt, which was longer than any other girl’s at school. I longed to go up into the branches, but I was too old now to climb trees, my father said.

That night, our power went out without warning, which meant Mom reached for our kerosene lamp and some candles, and we all lay in the dim firelight playing word games until we heard my father at the door.

My mother and I launched into a testimony of what had happened at school with the teacher. My father listened, pulling on his precept silently. His face looked weary in the candlelight. He held our world up on his shoulders, but I never once thought about what he was carrying. He flicked his locks over his shoulder and said, “They don’t know nuttin bout this Rasta trodition. Brainwashed Christian eejiat dem.” I nodded and smiled, ready for the big bangarang that would come next. But then he shook his head and said, “You need to keep your head down, do your work, and don’t cause no trouble.”

“I’m not. She was the one—”

“You’re on a scholarship. Don’t make no fuss,” he said again. “You hear me?”

“Yes, Daddy,” I said.

Later, my father came and lay next to me in bed. He was good at ignoring my moods, or eclipsing them entirely. “Now tell me again about school,” he said. I’d been regaling him weekly with which of my classmates’ fathers was a businessman and what kind of car each classmate’s mother drove. He seemed to relish these stories, so I hoarded details to report back to him. I might have found it hypocritical, but anything that lifted him meant the whole house lifted, too. As I spoke, his eyes closed.

“There’s a girl in my class whose father owns Margaritaville,” I began.

“He owns all of it?” he asked me, with a faraway voice.

“I think so,” I said. I wasn’t sure if that was true, but I knew the grander the parent’s success the more spirited he seemed.

“My daughter goes to school with the owner of Margaritaville,” he said, his voice drawn out with pride, if Rasta could feel proud.

This was what being thirty-four with four children and still no record deal looked like: one or two fewer dumplings on our plates, or shredded callaloo sautéed for breakfast and again for dinner. “Jah will provide,” Dad would say when food was short, and Mom would walk out into the yard and find something ripe—June plums or cherries—for us to eat.

My father was never going to be a carpenter or a banker or a taximan, he said. He sang for Jah, so he had no choice but to cover the same ten Bob Marley songs for tourists eating their steak dinners in the west-coast hotels. At home, though, he could still be king. My mother placed every meal before him as soon as he beckoned for it. He had never turned on a stove, never washed a dish. Every evening before he left for work, my mother would wash his dreadlocks, pouring warm anointments over his bowed head at the bathroom sink, and then oil each lock as he sat eating fruit that she had cut for him. I imagined a servant, just out of frame, fanning a palm frond back and forth.

One sweltering afternoon, Lij, Ife, and I found ourselves alone at home. Racing out to the yard, we crawled through the damp crabgrass, then galloped from bush to bush. We were glistening with sweat as we approached the cherry tree, which was so laden with unripe fruit that some branches scraped the grass. Each green cherry hung hard and bright like a little world.

I reached for one. It was crisp and tart, a bright tangy juice filling my mouth.

Soon the three of us were shaking the tree like locusts, jumping and snatching green cherries out of it two and three at a time, stuffing our mouths and laughing. “Let’s take some for Mommy and Daddy,” Ife said. I held out my T-shirt like a basket in front of me to catch the falling fruit.

It was not yet dark when our father hopped out of a taxi at the gate. He was back early, a bad sign. Perhaps his show had been cancelled. We ran up to greet him. Mom was not there to interpret the particular riddle of his face, but by the way he slammed the car door we should have known that he wasn’t to be bothered.

“Why unnu still outside?” he snapped. “Go bathe now,” he said, swatting us away.

In the living room, our father examined the state of us. Twigs in our dreadlocks, sweat and dirt on our foreheads, green stains down our shirts. He pointed to Lij’s bulging pockets.

“Fyah, whaddat?” he asked.

“Umm. Some . . . some cherries, Daddy,” Lij said.

“What yuh mean, cherry?” he said, cocking his head. “There is no cherry. The cherries are green.”

Lij explained that we had tried them. “They actually taste good!” he added.

My father’s smile did not reach his eyes.

“Don’t move,” he said, and walked out the door.

We heard him curse from the front yard. “Ah wha the bomboclaat!” he shouted, using a curse word usually reserved for record-label execs and hotel managers. His voice was ragged, unfamiliar. His footsteps pounded back up to the front door, which he slammed behind him. The walls shook in their frames.

He glared at us, and we were small, so small he could crush us under his heel. He began unbuckling the belt he was wearing. We had never seen him do this before. It was a new red leather belt that had been given to him by a Canadian friend, still shiny and stiff from lack of use. We looked at each other with confusion, soon mown down by fear as he pulled the red belt out from the loops of his khaki pants.

“Fruits fi eat when dem ripe,” he said, wrapping the belt in a loop around his fist. “Let every fruit ripen on Jah tree.”

“Daddy, we didn’t think—” I said, but couldn’t finish. I moved in closer to my siblings helplessly, close as I could get to them.

“The I them too unruly!” he roared, suddenly circling around behind us. He whipped the red belt down with stinging force across our backs.

Thwap. Thwap. Thwap. The world was upside down. I cried and pleaded, not to him but to something beyond him, anything that might make it stop. Everything was sideways then; roof and rubble crashing down on us, our little kingdom shattering.

When the beating was over, my father walked into his bedroom and drove a nail into the wall above his bed. There, next to another portrait of Haile Selassie, he hung the red belt, waiting for the next time his spirit bid him pull it down.

Not long after, I began detangling the roots of my hair, so it was dreadlocked only at the ends. Every morning before school, I brushed down those precious few inches of unmatted hair at my scalp and kept the strands soft and oiled at the roots. I started unbuttoning my school shirt one button down and wearing my tie at my chest, instead of at my neck, like a boy. Each time I looked in the mirror, I thought I might find something beautiful, as long as I didn’t open my mouth.

When I was fifteen, a few months before I graduated from high school, my mother found the money to get my tooth fixed. Suddenly, friends and acquaintances began suggesting I go into modelling. My mother heard that the Saint International modelling agency was scouting for models not far from where I was taking SAT prep classes.

At the entrance to the scouting event, a slim, bright-eyed man introduced himself as Deiwght Peters. He told me about the agency, which he had founded to celebrate Black beauty. While he spoke, he circled me with a feline liquidity, sizing me up like a museum artifact.

“You have a very unique look,” Deiwght told me, his eyes flitting over my dreadlocks, which had grown halfway down my back. “We have to get you,” he said, reaching for his Polaroid camera.

I don’t know what magic my mother worked behind the scenes, but my father, with a brooding resignation, agreed that I could sign on as a Saint model.

My grandmother lived in Spanish Town, near downtown Kingston, where a lot of fashion events took place, so it was decided that I would stay with her. Deiwght taught me how to glide with one heeled foot in front of the other without looking down, to appear both interesting and disinterested. Suddenly, I was moving in and out of the most beautiful clothes I had ever seen: turquoise pants and sequinned halters and ruffled dresses and stilettos. The first time I wore makeup, the makeup artist stepped away to show me my face in the mirror: “See? You barely need a thing, honey.”

My body was a gift, but I didn’t quite believe it, not until I sailed down that first runway as the crowd cheered on the Rasta mogeller who would be anointed in the next day’s paper. After the show, Deiwght grabbed my beaming mother and shook her, saying, “Your daughter? She is one of the classics!”

I began going to castings all over Kingston. Nighttime was always for poetry, and I spent the late hours at Grandma’s house nibbling away at the dictionary while writing by lamplight. I carried my poetry notebook wherever I went.

I had published my first poem, “Daddy,” at sixteen. The day it appeared in the literary-arts supplement of the Sunday Observer was one big excitement in the Sinclair household. I ran around announcing to everyone that my name would be in print. My father, who read the Sunday Observer every weekend, was the most excited of all of us, especially when he saw the title. I didn’t bother to warn him that it was not a tribute to him but a reimagining of a story in the news about a young girl who drank Gramoxone to kill herself because her father had molested her. I didn’t caution him that the language was visceral and the details gut-wrenching. Instead, I watched him as he opened the page, and savored the long droop of his face as it fell.

One weekend, my father stopped by Grandma’s house to pick me up for a model casting on his way to a meeting with music producers in Kingston. I had been instructed to dress for a music video that was “fun and young and sexy,” and I had made a short pin-striped pleated skirt from one of Grandma’s old skirts, adorning it with safety pins along the waist and hem, like a punk. My father honked impatiently as I walked out in my new outfit, trying to pretend I was bulletproof.

“Oh, Rasta,” he said, his eyes bulging as I swooped into the car. I tried to explain, but he wouldn’t look in my direction.

We pulled up outside a large iron gate in silence. Down a long gravel driveway, I could see a house, where brightly attired young people were milling about on a veranda. Instead of turning in to the driveway, my father pointed out my window. “It’s up there,” he said, still looking away from me.

I started to climb out of the car.

“I’m ashamed of you,” he said.

“O.K.,” I said, and started walking, surprised at how little I felt of the old humiliation.

In Miami, where I had flown a few months later with Deiwght, the older model leaned back in her chair. “Oh,” she said. “That’s a shame.” She looked from my face to my portfolio photos again and smiled politely. “The dreads just aren’t versatile enough.”

Foolishly, I had believed that my dreadlocks would make me one-of-a-kind in the fashion world, since I’d never seen a model with locks. But this was a profession in which one needed to be emptied of oneself, and I was still too much of my father.

Later that night, I called my mother and asked if I could cut my dreadlocks.

“Oh, Saf,” she sighed. “I think you already know the answer to that one.”

“Mom, I have no hope of doing this if I don’t.”

After a long pause, she said, “I will see.”

I learned that my father forbade me from cutting my dreadlocks. I knew that if I ever did I would not be allowed back under his roof. My hope for a new kind of life withered, and I had no choice but to return home.

In the end, my mother called a friend to help her. She chose a day when she knew my father would be gone. My siblings were at school, and her friend, whom I’ll call Sister Idara, arrived with a smile, ready. I closed my eyes and leaned my head over the laundry sink. The two women poured cupfuls of hot water over my scalp to soften the hair, massaged my roots with their hands, and then lathered my dreadlocks and scrubbed. They lifted me up and wrapped my damp hair in a towel. We three walked together arm in arm to my bedroom. The window curtain lifted in the breeze as I knelt between my mother’s knees and waited.

“I went through this with my eldest daughter, too,” Sister Idara said. “After all the anger, we got through it. Distance helps, of course.”

Sister Idara was an American, the wife of a friend of my father’s, and lived abroad with her two children for most of the year. She was a plump and jovial Rastawoman who kept her dreadlocks and body shrouded in matching African fabrics. My mother had asked her to be here because she was a perfect shield. My father could not unleash his anger on his good bredren’s wife, and she was scheduled to fly back to the States the next day, so he would be able to spit fire only over the phone. “Have you told him we’re doing it?” I asked my mom. “No,” she said. “But I don’t need his permission.”

Mom told me to hold down my head. She asked me if I was ready, and I said yes. This was the first time since birth that my hair would be cut. I don’t know who held the scissors or who made the first cut. All I heard were the hinges of the shears locking and unlocking, the blades cutting. And then long black reeds of hair came loose in their quick hands. I closed my eyes then, because I could not look at what I was losing. I had not expected it to matter when the moment came. But now I found that it mattered a great deal.

There was hair. So much hair. Dead hair, hair of my gone self, wisps of spiderweb hair, old uniform-lint hair, pillow-sponge and tangerine-strings hair. A whole life pulled itself up by my hair, the hair that locked the year I broke my tooth. Hair of our lean years, hair of the fat, pollen-of-marigolds hair, my mother’s aloe-vera hair, my sisters weaving wild ixoras in my hair, the pull-of-the-tides hair, grits-of-sand hair, hair of salt tears, hair of my binding, hair of my unbeautiful wanting, hair of his bitter words, hair of the cruel world, hair roping me to my father’s belt, hair wrestling the taunts of baldheads in the street, hair of my lone self, all cut away from me.

When they were finished, my neck and head were so light they swung unsteadily. The tethers had been cut from me, and I was new again, unburdened. Someone different, I told myself. A girl who could choose what happened next.

0 notes

Text

By Safiya Sinclair

The first time I left Jamaica, I was seventeen. I’d graduated from high school two years before, and while trying to get myself to college I’d been scouted as a model. And so I found myself at the Wilhelmina Models office in Miami, surrounded by South Beach’s finest glass windows with all my glass hopes, face to face with a famous one-named model who was now in her sixties. When her gaze halted at my dreadlocks, I shouldn’t have been surprised at what came next.

“Can you cut the dreads?” she asked, as she flipped through my portfolio, her soft accent blunting the impact of the words.

Back home in Kingston, hair stylists would leave my dreadlocks untouched, tied up in a ponytail with my good black ribbon, deciding that the problem of my hair was insolvable.

“Sorry,” I said. “My father won’t allow me.”

She glanced over at the agent who had brought me in.

“It’s her religion,” he explained. “Her father is Rastafarian. Very strict.”

The road between my father and me was woven in my hair, long spools of dreadlocks tethering me to him, across time, across space. Everywhere I went, I wore his mark, a sign to the bredren in his Rastafari circle that he had his house under control. Once, when I was feeling brave, I had asked my father why he chose Rastafari for himself, for us. “I and I don’t choose Rasta,” he told me, using the plural “I” because Jah’s spirit is always with a Rasta bredren. “I and I was born Rasta.” I turned his reply over in my mouth like a coin.

My father, Djani, had also been seventeen when he took his first trip out of Jamaica. He travelled to New York in the winter of 1979 to find his fortune. It was there, in the city’s public libraries, that my father first read the speeches of Haile Selassie and learned about the history of the Rastafari movement. In the early nineteen-thirties, the street preacher Leonard Percival Howell heeded what is known as the Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey’s call to “look to Africa for the crowning of a Black king,” who would herald Black liberation. Howell discovered Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia, the only African nation never to be colonized, and declared that God had been reincarnated. Inspired by Haile Selassie’s reign, the movement hardened around a militant belief in Black independence, a dream that would be realized only by breaking the shackles of colonization.

As he read, my father became aware of the racist downpression of the Black man happening in America. He understood then what Rastas had been saying all along, that systemic injustice across the world flowed from one huge, interconnected, and malevolent source, the rotting heart of all iniquity: what the Rastafari call Babylon. Babylon was the government that had outlawed them, the police that had pummelled them, the church that had damned them to hellfire. Babylon was the sinister and violent forces born of western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people. It was the threat of destruction that crept even now toward every Rasta family.

Just as a tree knows how to bear fruit, my father would say, he knew then what he needed to do. On a cold day in February, his eighteenth birthday, my father stood before a mirror in New York City and began twisting his Afro into dreadlocks, the sacred marker of Rastafari livity, a holy expression of righteousness and his belief in Jah. When he returned to Jamaica, his mother took one look at his hair and refused to let him into the house. It was shameful to have a Rasta son, she said. My father, with nowhere else to go, reluctantly cut his hair back down to an Afro.

Soon my father began spending time around a drum circle with Rasta elders in Montego Bay, sitting in on the spiritual and philosophical discussions that Rastas call reasoning. “Rasta is not a religion,” my father always said. “Rasta is a calling. A way of life.” There is no united doctrine, no holy book of Rastafari principles. There is only the wisdom passed down from elder Rasta bredren, the teachings of reggae songs from conscious Rasta musicians, and the radical Pan-Africanism of revolutionaries like Garvey and Malcolm X. My father felt called to a branch known as the Mansion of Nyabinghi, the strictest and most radical sect of Rastafari. Its unbending tenets taught him what to eat, how to live, and how to fortify his mind against Babylon’s “ism and schism”—colonialism, racism, capitalism, and all the other evil systems of western ideology that sought to destroy the Black man. “Fire bun Babylon!” the Rasta bredren chanted every night, and the words took root in him. He was ready to decimate any heathen who stood in his way.

Hanging on the mint-green living-room wall of our family’s house in Bogue Heights, a hillside community overlooking Montego Bay, was a portrait of Haile Selassie, gilded and sceptered at his coronation, his eyes as black as meteorites. It was flanked by a poster of Bob Marley and a photograph of my father, both onstage, both throwing their dreadlocks like live wires into the air.

Every morning of my childhood began the same way, with the dizzying smell of ganja slowly pulling me awake. My mother, Esther, who had first embraced the Rastafari way of life when she met my father at nineteen, was always up before dawn, communing with the crickets, busying herself with housework and yard work. Whenever she worked, she smoked marijuana. The scent of it clung to her long auburn dreadlocks. She carried a golden packet of rolling paper on her at all times, stamped with a drawing of the Lion of Judah waving the Ethiopian flag, the adopted symbol of the Rastafari. My brother, Lij, my sister, Ife, and I pawed and pulled at her, but she did not mind. If she was with us, she was ours.

My father was the lead singer in a reggae band called Djani and the Public Works. When I was seven, Lij five, and Ife three, he met some Japanese record-label executives at the hotel where the band performed nightly, and they agreed to fly the musicians to Tokyo to play reggae shows. They stayed for six months and recorded their first album. After he left, my mother cleared our back yard and planted some crops, which soon became towering stalks of sugarcane, a roving pumpkin patch, and vines and vines of gungo peas, all exploding outward in swaths of green. We had always kept to an Ital diet: no meat, no fish, no eggs, no dairy, no salt, no sugar, no black pepper, no MSG, no processed substances. Our bodies were Jah’s temple.

Early on school mornings, under the watchful eye of the holy trinity, my mother combed my black thundercloud of hair, often with me tearfully begging her to stop. Once, the children at my grandmother’s Seventh-day Adventist church had asked me why I didn’t have dreadlocks like my parents; I remembered the certainty in my grandma’s voice when she said that we would be able to choose how to wear our hair.

Even though the combing was painful, I still wouldn’t have chosen dreadlocks. When my mother was finished, I swung my glistening plaits, fitted with blue clips to match my school uniform, back and forth, back and forth, pink with delight. I felt it was all worth it then. My mother made it look easy, corralling three children by herself to school every morning while my father was away.

Babylon came for us eventually, even in our kingdom of god-sent green. One Sunday during our Christmas break, my mother dragged a comb across my head and gasped. Two large fistfuls of hair were stuck in its teeth, yanked loose like weak weeds from dirt. I screamed.

“Oh, Jah. Oh, Jah. Oh, Jah,” she said, holding me as I cried, blocking my hand from trying to touch my scalp, where I now had a bald spot. Ife was fine, but Lij’s hair was also falling out in clumps. My father distrusted Babylon’s doctors. My mother did, too—until she had children.

We had been infected with barber disease, the doctor told us, a kind of ringworm spread first by barbers’ tools, then by children touching heads at school. Babylon’s disease. Mom closed her eyes as she listened. The doctor prescribed a thick antifungal cream and a chemical shampoo.

A week later, despite the treatment, there was scant improvement. My mother gathered up all the combs in the house and flung them into a trash bag, along with the medicine. Hair for the Rastafari signified strength. My father called his hair a crown, his locks a mane, his beard a precept. What grew from our heads was supposed to be most holy. My mother took our blighted scalps as a moral failure, ashamed that we had fallen to Babylon’s ruin so soon after my father had gone.

For the rest of the break, she tended to our heads with a homemade tincture. After a few days, my hair started growing back. “Praise Jah,” Mom said, as she began the process of twisting all our hair into dreadlocks. Day after day, we sat, snug between her legs, as she lathered our heads in aloe-vera gel and warm olive oil.

Within a few weeks, my hair had stiffened and matted into sprouts of thick antennae, bursting from my head. There was no turning back now. From that point on, combing and brushing our hair was forbidden, on a growing list of NO.

When my siblings and I returned to our primary school after the break, the students gawked at us as if we were a trio of aliens disembarking from a spaceship. They crowded around, trying to sniff or pull at our locks. If they could have dissected us alive, I think they would have.

Not long after, a sixth grader began shadowing me. She crept up close while singing in my ear, “Lice is killing the Rasta, lice is killing the Rasta,” a widespread taunt in the nineties, which co-opted the tune of a popular reggae song.

My cheeks stung in humiliation. For the first time, I felt ashamed to be myself. At lunchtime, I told my brother about the girl, her needling insult. My brother shook his head and kissed his teeth the way grownups did.

“Saf, don’t pay her no mind. All ah dem a duppy,” he said. “And we are the duppy conquerors.” He was trying to sound like a big man, talking like our father.

I tried to imagine what my father would say. He always told me to be polite but right. “I man and your mother didn’t birth no weakheart,” he said. “Always stand up for what you know is right. You overstand?” Even from afar, his mind moved mine like a backgammon piece.

I decided to go to the teachers’ lounge and tell my third-grade teacher about the girl’s teasing. Tapping me gently on the shoulder, she told me that with my good grades I should pay such things no mind.

As I walked away, still pensive, I heard her and some of the other teachers talking.

“But it’s a shame, innuh,” a new teacher’s voice chimed in. “I really thought the parents were going to give them the choice.”

We were under our favorite mango tree by the front gate when a car rolled up one day in early May. Suddenly, my father appeared like the sun, beeping the horn and flashing his perfect teeth at the sight of us. We jumped on him, and cried; the fireworks of feelings had nowhere else to go. He brought in a parade of bags and boxes from Japan, a brand-new electric Fender guitar slung across his back. He was buoyant. All afternoon, he kept touching his fingers to our dreadlocks. We could tell he was pleased.

Inside the house, he unzipped his suitcases and showered us with mounds of stuffed toys, exquisite notebooks, new clothes and shoes, and a Nintendo Game Boy with Japanese cartridges. For Mom, he brought fancy lotions, a robe, and packets of something called miso. We cheered at every new gift. My father was our Santa, if Rasta believed in Babylon’s fables.

Dad was home with us that entire summer. Every day, he was a more carefree version of himself. He taught us to play cricket, told us the same ten jokes of his childhood, and dazzled us with his tree-climbing skills. His recording contract was for two years, but the record label could obtain only six-month visas for the band at a time. Once school began, he went back to Japan to finish the album. We didn’t have a phone, so we visited the shop of his closest bredren, Ika Tafara, to call him every weekend.

By the time we walked into Ika’s shop for the Kwanzaa celebration that December, I felt like I belonged. About thirty Rasta bredren and their families had come from all over Mobay to gather and give thanks. We recited Marcus Garvey’s words like scripture. I played the conga drum and sang of Black upliftment with other Rasta children. There were about twenty of us there, peeking from behind our mothers’ hems. And though he was across the sea, my father felt present, the sound of his voice ringing out through the store’s speakers.

But when my father got back the second time, the following May, he seemed different. His relationship with one of his bandmates had imploded, taking the band’s hopes with it, and he was once again playing reggae for tourists at the hotels lining the coast. My sister Shari was born a month after his return. With the birth of another Sinclair daughter, my father’s control over us tightened. One afternoon, he decided that my siblings and I needed to be purified. I watched him stalk through the yard, pulling up cerasee leaves, bitter roots, and black vines, which my mother blended into a pungent goop and poured into three big glasses. He loomed over us for what seemed like hours, as we bawled and retched, struggling to swallow the foul potion. We were there until night fell, until my father believed we had finally been cleansed.

“The I them have to be vigilant,” he said when it was over. Our joy had made us heedless, easy prey for the wicked world. We would no longer be allowed to run around outside, or even to leave the yard. “Chicken merry, hawk deh near,” he reminded us.

“I man don’t want my daughters dressing like no Jezebel,” he told my mother later. At his instruction, she threw out every pair of pants and shorts my sisters and I owned. Now we would wear only skirts and dresses made from kente cloth, as our mother did. Our hems were to fall below our knees, our chest and midriff to be covered at all times. Pierced ears, jewelry, and makeup—all those garish trappings of Babylon—were forbidden. “And once you reach the right age,” my father said, “the I will wrap your locks in a tie-head like your mother.” I realized I had been naïve, in not expecting that this was the life my father had imagined for me.

My hair hadn’t been brushed in two years. Flecks of lint and old matter knotted down the length of each dreadlock, a nest containing every place I had laid my head. Dad caught me pushing my fingers through the thicket of roots in the bathroom mirror once, as I tried to twist the crown of my hair into shape.

“Stop that,” he said. “Hair fi grow. Naturally and natural only. Like Jah intended.”

“Yes, Daddy,” I said.

With each month came a new revocation, a new rule. Soon he didn’t even allow us around other Rastafari people. He trusted no one, not even them, with our livity. In our household rose a new gospel, a new church, a new Sinclair sect. The Mansion of Djani.

Whenever our father was out of the house, which was almost nightly, my siblings and I resumed our outdoor play. One day, a few weeks later, Lij chased me across the lawn. I zipped left and ran sideways into the house to lose him. But there he was again. Laughing, I turned to face him, and his running motion drove the full force of his body into my jaw, which slammed hard against the bathroom wall. I felt my front tooth crumble to chalk in my mouth. I slid my tongue across my gums and found a sharp crag in the place where my tooth used to be, and sobbed.

My parents couldn’t afford to fix my tooth. They didn’t have insurance, and a dentist friend told them it didn’t make sense to get it capped until I was older anyway, because my mouth was still growing. I wanted to protest, but I knew my father thought that my distress over my tooth was only vanity, and vanity was a mark of Babylon. I suspect he liked me this way. My mouth was now a barricade between me and the onslaught of adolescence, a broke-glass fence around my body.

I stopped smiling. At school, I sat clench-mouthed and held my hand across my mouth whenever I spoke.

At the end of the school year, there was a carnival. Venders came with cotton candy and peanut brittle and their bright pandemonium of wares. One of the attractions was a mule ride, and after some begging my mother said Ife and I could do it. I pulled my hand-sewn dress over my knees and got on the mule sidesaddle. As we were led around the parking lot by the animal’s owner, a photographer appeared and snapped our picture; I made sure to shut my mouth tight. The next day, the local newspaper printed the photo in a half-page spread, my face gloomy above the caption “Two Rasta girls riding a mule.”

One morning, when I was nearing the end of sixth grade, my mother held up the classifieds in excitement. “Look at this, Djani,” she said. There was an ad announcing two scholarships for “gifted and underprivileged” students to attend a new private high school called St. James College, in Montego Bay. For my parents, this would mean tuition paid, uniforms made, one less child to worry about. A burden lifted. Students had to apply, and a chosen few would then be interviewed by the school’s founders.