#Welding Trade School philadelphia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Emerging welding techniques are revolutionizing the welding jobs in 2025. Read more about such techniques if you are an aspiring welding technician.

#welding certification courses in philadelphia#welding course for beginners in philadelphia#welding training courses in philadelphia#professional welding courses in philadelphia#welding trade school requirements in philadelphia#welding technology course in philadelphia#Advanced welding courses in philadelphia#Welding certification training in philadelphia#welding training and certification courses in philadelphia#advanced welding certificate in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

PTTI's Welding Program transforms students into skilled welding wizards. Through precision techniques, trainees mold steel into intricate designs. Welding sparks illuminate their dedication, forging a path to a future where they craft masterpieces from molten metal. At PTTI, they sculpt their dreams in metal.

#welder classes in philadelphia#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welding certification training in philadelphia#philadelphia welding schools#welding schools in philadelphia#welding training philadelphia#welder school in philadelphia#best welding trade schools in philadelphia#certified welder school in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa

0 notes

Text

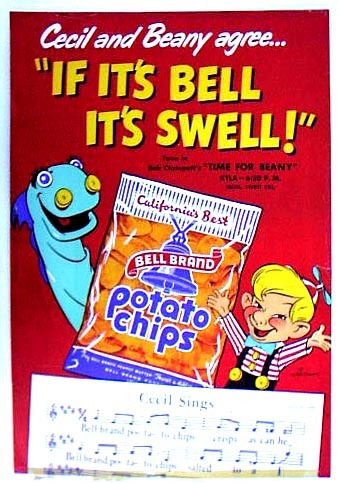

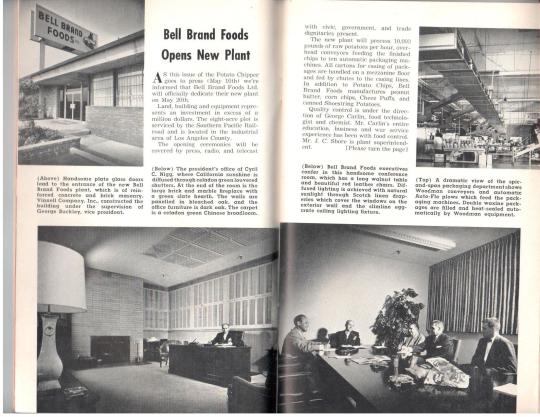

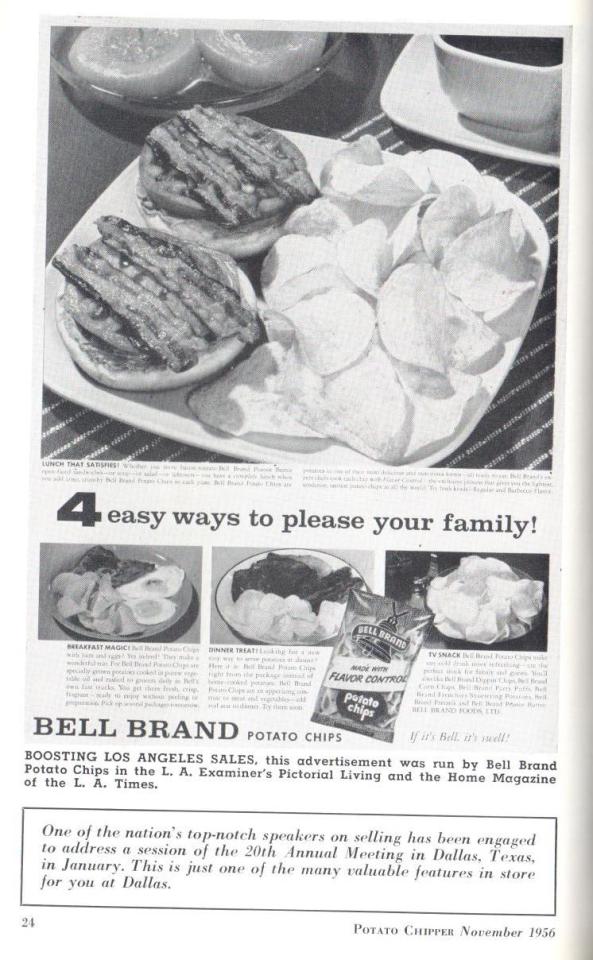

If It's Bell, It's Swell

What do Sandy Koufax, Marilyn Monroe and Beany and Cecil all have in common? They were all promoted by Bell Potato Chips.

Sometimes the history of various potato chip manufacturers (chippers) has been passed down from generation. In an attempt to preserve and document the history regarding Bell Brand, I have included interviews of many people.

The following is based on a statement by Craig Scharlin, grandson of the founder of Bell Potato Chips., Max Ginsburg.

Bell Brand Potato Chips was a privately owned company started in the 1920's by Max I. Ginsberg. He was an immigrant from the Ukraine who came to the US on his own at the age of seven. He met up with his brother in Philadelphia and started selling hand made pretzels on the streets. He moved to Los Angeles in the teens and in the early 1920's started his own company named the L.A. Potato Chip and Pretzel Company which he eventually changed the name to Bell Brand Potato Chips. He named it Bell after the bells of the Spanish Missions of California and because he thought the name Bell made people happy. He created the slogan, "If it's Bell it's Swell" and also created the name Frenchie for the shoe string potato chip. Bell Brand Potato Chips was one of the sponsors of the Jack Benny Radio Show in the 1930's among many others. One of his best friends and founder of Ralph's Grocery stores, Mr. Lawry, also owner of the famous Lawry's Prime Rib restaurants of Los Angeles and the Tam 'O Shanter Restaurant in Glendale, was one of his major buyers. Max Ginsberg decided to retire in the 1950's.

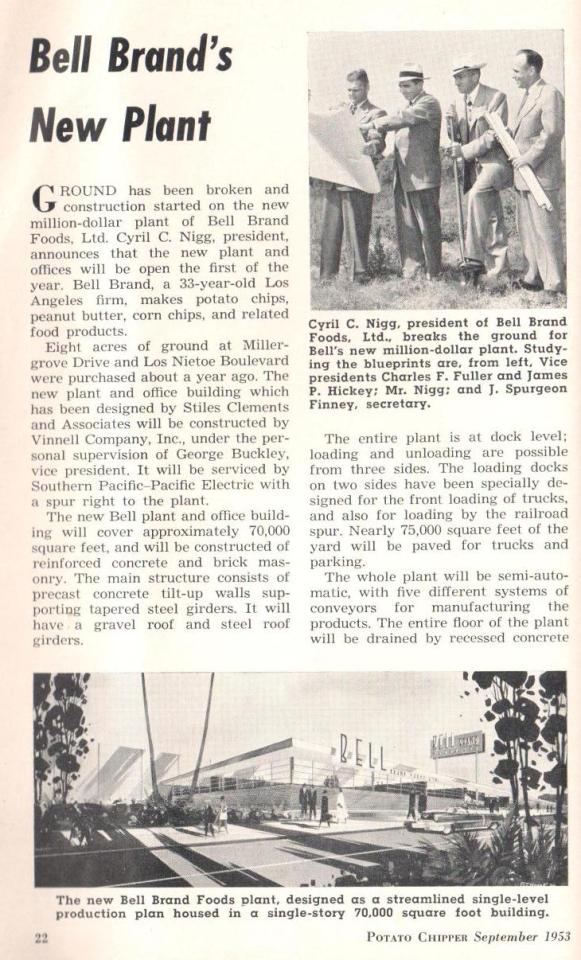

My mentor, the late Donald Noss who was the son the the founder of the snack food trade association, gave me his extensive archive regarding the potato chip industry. Among the items was the attached photo of four men. The back of it was inscribed " J. Spurgeon Finney, Cy Nigg, James Hickey & Chas. Fuller.

Finney was Treasurer and Hickey and Fuller were vice presidents of Bell Brand. Below, you will learn more about Hickey and Fuller and how they obtained their ownership shares. Lizette Gabriel of the Los Angeles Public Library provided me with the link to the oral history of Cyril Nigg as part of the research into the Tom Sawyer Foods. When I read it, I was able to match three of the four people in the photo with their names. In a true sense, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Cyril Nigg had worked his way up the chain at Kellogg's, the cereal maker, by staying after other suppliers had left for the day to help grocers with their tasks such as inventory management, pricing inventory including items that he was not supplying, in a manner that developed great trust and strong relationships. This enables Nigg to get the grocers to include his products in their ads, provide him with prominent display space for the Kellogg's brands. He was a pioneer at creating combinations , trade promotions where he would put together two or three packages of Kellogg's cereals with a premium: cereal bowl, muffin tins, rag dolls. Nigg created the cereal department that now is a standard department in all grocery stores. He also conceived of quantity discounts for grocers. He was also one of the first to sell the entire line of Kellogg's cereals, whereas most others only sold one or two.

He was told that he would be groomed to be the President of Kellogg's by moving every couple of years to different parts of the county to learn the diverse markets. With children in high school and both his and his wife's family in Los Angeles, he decided that he would prefer to stay in the Los Angeles area. Taking a job with another large employer would most likely also require him to relocate. Because of his relationships within the food industry, he agreed to chair the Red Cross Appeal within the food industry division. Based on an oral history from the California State archives in 1993, Nigg tells the story of how he entered the potato chip business in his own words:

NIGG: I had one [Red Cross Appeal] card, a guy by the name of Max Ginsberg, who I knew real well, who owned the [Los Angeles] L.A. Saratoga Chip and Pretzel Company. He was a member of the sales managers club. I knew him well. He had given $500 the year before, and in those days $500 was a pretty good contribution for Red Cross. I didn't want to miss him. I called two or three times, and he's not in. Finally I say to the girl at the telephone, "Well, when will Mr. Ginsberg be there? I'm working for the Red Cross drive." "Oh," she said, "Mr. Ginsberg is just horne from the hospital. He's been very ill." Oh, I was sick. Here's my 500-buck contribution, and he's not going to be able to corne in. So I thought, "Well, maybe I can go by his house." I knew him pretty well. I thought, "I'll go by his house and see how he is, and maybe I can say something about the Red Cross drive." So I go by. He lived up in the Los Feliz area. His wife lets me in. He comes in, and he looks like walking death. God, it was a shock to me! I knew him, and here's this guy looking so terrible. I said, "Max, what's wrong with you?" "0h," he said, "I go down to the plant, I get all upset. Nothing is going right." Now, again, the war is on. You can't get help, you can't do this. So he gets all upset. He was the kind of an owner-manager who had to be in on everything. [If they] bought a new typewriter, he had to say what one they'd buy. So he goes down, and he gets all upset. He says, "My doctor says get rid of the business or get a new doctor. II So he said, "I guess I'm going to have to sell my business." Without thinking, I said, "Max, I'd like to buy iL" And he said, "Cy, everybody wants to buy my business, but my wife and I worked so hard to build it. They'll ruin it, I know. There's nobody I'd rather have than you.

So just that easily I bought that business. We came to an easy agreement. I paid him $100,000 for the business, plus the inventory, plus the accounts receivable. Inventory and accounts receivable were each about $25,000, but I could finance that easily. So my only thing was the $100,000, and I made arrangements. It was easy to get the money. The first person I told was a boy by the name of [James P.] Jim Hickey. [He had] been in Loyola High School with me, same class. He'd gone on to studying medicine back at Saint Louis and ran out of money. He was running a Standard Oil [gas] station at Olympic [Boulevard] and Fairfax [Avenue], kind of a training station, and working like the dickens. Oh, he was good. So I said to Ted Von der Abe, my friend whose office was right across the street, "You ought to hire that Jim Hickey. Boy, he's good." But Ted didn't do anything, so I hired him, and he came to work for the Kellogg Company. By now he's my assistant, he's my supervisor. So we're still working Saturdays, and Jim and I go to lunch, and I tell him, "Jim, I'm leaving the company. I'm going to buyout Max Ginsberg." He said, "I'll go with you." I said, "Jim, are you crazy? You'll get the job. This is what you've been working for. I'll recommend you." "No," he said, "we've always been together. I'll stay with you." Well, I said, "Jim, that wouldn't be right. I can't hire you. I'm taking a gamble. For you to come to work for me, that would be crazy. You stay with Kellogg's." "No," he said, "we've always been together. I like working with you. I'll stay with you." So I said, "Jim, I would love to have you, but I just can't hire you. I'm paying $100,000 for this business. If you could raise $10,000, you'll have a 10 percent interest. Then you have the same chance I have." He said, "I think my Uncle Tom would help me. will you go with me to see him?" I said, "Sure." So we go out to see Uncle Tom. Uncle Tom is Tom Hickey, Hickey Pipe and Supply Company, who's been very successful. He likes Jim; they're very close. So we go out, and I tell Tom what I'm going to do, and Jim wants to buy a 10 percent interest and he needs $10,000. Tom says to Jim, "Is that what you want, Jim?" And Jim says, "I think it would be such a great opportunity." Tom says, "I'll arrange it." So Tom got Jim a loan for $10,000 from the bank, and so he's my partner. I'm going to be the general partner, and he'll be a limited partner.

The next week, a fellow by the name of [Charles] Charley Fuller, who had worked for me, who is now the general manager of a little honey company.. And, of course, in those .. War's on. You can sell all the honey you can get. The job was to get it and get it bottled, that sort of thing. So Charley comes to see me. He said, "I hear you and Jim are buying out Max Ginsberg." I said, "That's right." He said, "Well, look. I don't know much about production, but I know more than you guys do. How about taking me and letting me be the production manager?" I said, "Charley, I'll give you the same deal I gave to Jim. You raise $10,000, you'll have a 10 percent interest." Well, Charley didn't have an Uncle Tom. [Laughter] So he had to work awfully hard. But he went to all of his friends, and he'd borrow $100 here, $1,000 here. Ted Von der Abe gave him $5,000. That was his big one. He borrowed on his insurance; he borrowed on his house. Finally he gets his 10,000 bucks. So now it's the three of us. We took over February 1 of 1945. The war's still on. We have all these friends in the food industry who know us and love us, want to help us. The first month, we doubled the volume. The first month we did twice as much business as Max had done in January. The next month, March, we almost doubled it again. So we had this rapid, tremendous growth.

We recognized that we needed the money in the business. We're expanding so rapidly, we need all the money we can keep in the business. And as partners, individuals, at the end of the year weld have to payout all this money in taxes. So I go down to see my friend Tom Deane at Bank of America, tell him the problem, where we are. He gets on the phone and calls upstairs to the eighth floor to Claude A. Parker Company and says, "Cy, go up and visit with them. They're real experts." So I went up to see a man by the name of Theo Parker, and I told him the whole situation. "Well," he said, "are you building this business to sell it?" I said, "Oh, no, no. We just want to build a business." "Are you building it to maybe sell stock?" "No, we want to keep it. It's our business. We want to keep it." "Oh," he said, "okay, then this is how we'll do it. We'll expense everything we can. Rather than buy something, we'll repair something. You own it, so it doesn't make any difference. If you're going to sell the business, you want assets. If you want to sell stock, you need assets. But that isn't going to be your situation. You're just going to own this thing, it's going to be yours, so we'll expense everything we can." So that's the way we did it. We built that business, had great growth.

The war ended, men came out of the service, and we were able to have such a great choice of young men for our sales department, for our production department, for everything we did. We put together this great organization. Now, as we put together this great organization, that freed me so that I could be out in other activities, be active with UCLA alumni. When I became president [of the Alumni Association] and became a [University of California] regent, I gave five days a month to the university. For two years I gave five days a month. One of those days went to committee meetings, the second day was to regents meetings, the other three days were just to university activities. There were all kinds of things I had to be active in, but I was free to do it because I had this great organization.

TRELEVEN (Dale E. Treleven of the Oral History Program University of California, Los Angeles Who Is the Interviewer): Okay. Now, the name of the company remained the same or ?

NIGG: No, no. His name was L.A. Saratoga Chip and Pretzel Company. His trademark was a mission bell. We liked the bell, so we called our company Bell Brand Foods, Limited--Limited because it was a limited partnership to begin with. We never changed that. We kept that name, Bell Brands Foods, Limited.

TRELEVEN: Where does Tom Sawyer come in? Your regents 68 biography said you were chairman of the board of Tom Sawyer Foods, Incorporated.

NIGG: Tom Sawyer was a competitor, and, I don't know, five, ten years down the line we bought them out. So we now own Tom Sawyer Foods. Tom Sawyer Foods was a competitor in potato chips. They had a big nut meat department and a big candy department, so

TRELEVEN: So that's what you did. And that's not all you did, but in terms of the business in which you were engaged, that you kept at until what year?

NIGG: Let me give you the background of that now. We were successful from the day we took over, highly successful. It grew and it grew, and we built this great organization. I put Tom Deane, the manager of the head office of Bank of America, on our board of directors.

* * *

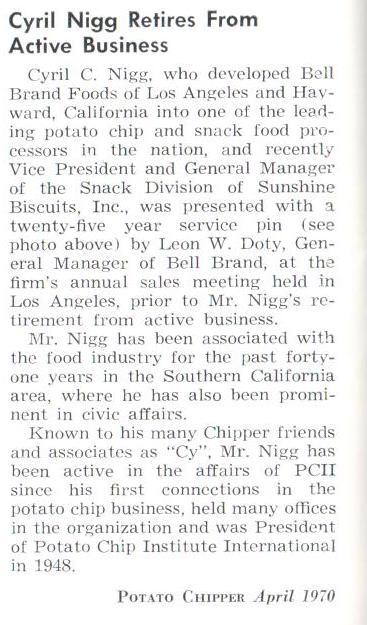

By now I had made my son chairman of our board and my son-in-law [Leon Doty] president of the company. 72 They were a couple of young, dynamic guys. They went to the UCLA School of Business Administration that, you know, you worked in .... What do you call that program?

TRELEVEN: Well, is it an internship program? Or is it the MBA [masters of business administration] program, perhaps?

NIGG: Well, you went to school nights. You worked daytimes. In other words, they stayed on the job but went through that whole program. Harvard [University] had started the thing. They did it, and then UCLA took it up. Anyhow, they did that program. They're sharp young guys. They really are sharp, working hard, really know their stuff. So I said to Peter, my son, "Now, your job as chairman is to see that we continue the rate of growth we've always had." "I understand." "Leon, my son-in-law, you're going to be the president. You just run this company like you .... Just make it go." And he did. He was a terrific guy. So we're growing, we're very successful. But about 1967, my son comes to me and says, "You told me to keep it growing. We can find new products, we can find new territory, we can maintain the growth, but we're going to run out of money. We won't generate money fast enough to keep up that rate of growth." Now, at that time, everybody wanted to buy us. It was a time of mergers. Every month I just had somebody corning and wanting to buy us. And I'd always say, "We're just not interested at all. Forget it." Well, a friend of mine [Harry Bleich] at Sunshine Biscuit [Company]--and they had quite a few plants around the country--had said to me, "Cy, if you ever want to sell, corne to see me. I know you don't want to now, but maybe sometime in the future, corne to see me." So when my son said to me, "This is what I recommend," we held a board meeting. He explained the situation, and everybody agreed, well, maybe it's the time to look around. Let's see what we can do. So I go back to New York and talk to my friend at Sunshine Biscuit. I said, "Maybe now is the time. We're at least ready to talk." He takes me into the president of the company, and the guy says, "When will you be back in Los Angeles?" And I said, "Tomorrow." He looks at his calendar, and he said, "I'll be there next Tuesday." This was the American Tobacco Company. They later changed the name to American Brands, but it was the American Tobacco Company. They've got to diversify; they know this. They're in the tobacco business. All this talk against tobacco companies and the tobacco industry, they've got to diversify. And they had Sunshine Biscuit. So this fellow comes out. I show him around, tell him what we've got, what we can do. He's very impressed. They want to buy us, but they want to buy us for cash. Well, we couldn't sell for cash. We start with zero, and now we're up into the millions, and the whole thing would be taxable. So I said, "No. I want common stock. If we can't have common stock, there's nothing to talk about." Well, this was a big concession for them, but they made it. So they bought us for common stock. I agreed to stay on, which I did. On the board? On the board and as.... They now are making me in charge of all of their snack food businesses around the country. So I got in, and I worked pretty hard, did pretty well. But then in a big company like that you've got all these internal politics going on, and somebody else was coming up into power, and I didn't like it. Yeah, and you were about in your early sixties. No, I'm sixty-five. So I said, "I'm sixty-five. Time to retire." So I retired. My son quit immediately. My son-in-law stayed on, but by now you've got to report to New York, and then you.. Before, he could just do anything he wanted to do. Now you've got to get permission. So he got tired of it, and he left. We were fortunate; we had that American Brands stock. It paid a good dividend year after year after year. It doubled, I'm going to say, six times. So we did very, very well. I still own a bunch of it, and now it's going down, but over the years it did very, very well. So that's that.

You can read the entire oral history of Mr. Nigg's remarkable career at

http://archives.cdn.sos.ca.gov/oral-history/pdf/nigg.pdf

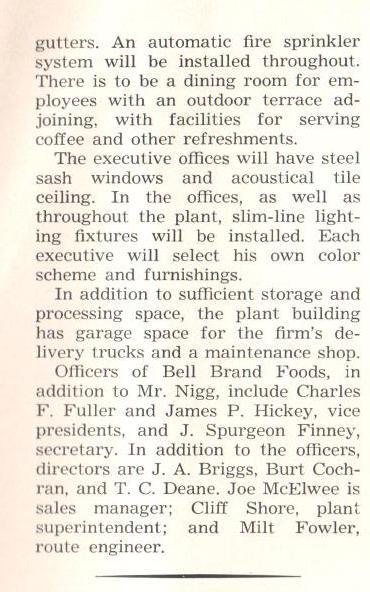

The attached article entitled "3 Ingredients for Success Freshness, Quality, Flavor, Plus Wuse Management Tell the Story Behind Growth of Bell Brand Foods" in the September 1953 Los Angeles Times provides some of the company's history as well as its corporate philosophy:

HUGE BUSINESS INCREASE

Thirty-three years ago [1920] production began as Bell Brand potato chips in Los Angeles. "production" meant that at the start only two people worked to slice the potatoes, cook them, package them, and deliver them.

But although the plant personnel was small, the product was good from the start and business grew steadily though not spectacularly from year to year.

Eight years ago Cyril C. Nigg, nationally known food products merchandiser, took the helm of Bell Brand foods Ltd.. In these few swiftly rolling years Bell Brand potato chip sales increased eight times over the sales of 1944, the year before he became president. . . . 100% increase over the the original figure for each eventful year.

Trained experienced leadership and TEAMWORK by executive personnel are the decisive factors in the Success Story . . . a product of the American system of individual initiative and free enterprise.

Cyril Nigg had been Southern California manager for one of the largest manufacturers and merchandisers of breakfast food products. Not only as a leader in his specialized industry, but as an expert of food problems, he recognized the place that properly prepared and delivered potato chips would have on Southern California dining table.

That is why he and his associates placed their resources of mind and experience and finance behind Bell Brand.

FRESHNESS, QUALITY, FLAVOR

Cyril Nigg and his organization knew that the words "Potato Chips " are like the name of any other product . . . they do not in themselves spell quality or satisfaction; three other very important "ingredients" are required:

Freshness, Quality, Flavor

These words proclaim the standard of production aimed at and achieved by Bell Brand.

Mr. Nigg and his notable executive "team" Charles F. Fuller and James P. Hickey , vice presidents, and J. Spurgeon Finney, treasurer, knew from the start what it takes to please the great American customer.

Bell Brand potato chips MUST be delivered fresh and sold fresh.

Top quality must be accomplished by using selected potatoes and finest cooking oils only.

Just the right truly delicious flavor must be attained. This is delivered by a combination of selected potatoes, pure golden vegetable oil, PLUS exactly right timing in the frying process. . . timing that results in building the flavor and creating rich golden shade for the chips.

Finally, Bell Brand Potato Chips are delivered in double waxine packages, heavy enough for protection against sunlight, heavy enough in keep air out and keep in freshness, flavor and aroma.

Bell Brand packages are marked by a special code indicating when delivery was made and any not sold promptly are reclaimed by the plant.

QUALITY KNOWS NO SUBSTITUTE

It is splendid to have a product that will please everybody. It is another thing to get everybody to buy and enjoy it.

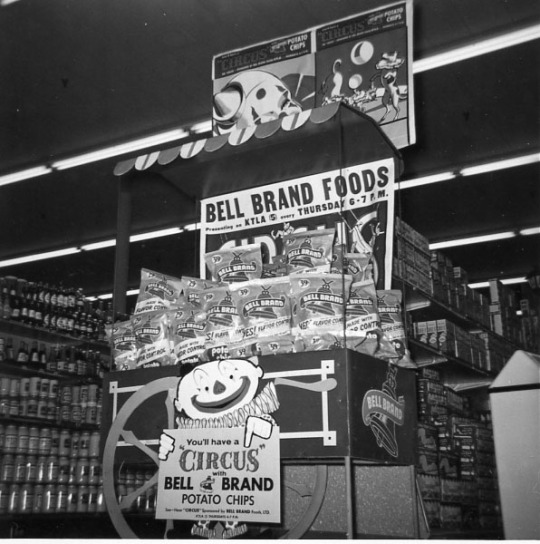

Enterprise and sustained advertising and merchandising and advertising have keynoted Bell Brand's campaign. Hundreds of thousands of Southern Californians are familiar with the appetizing pictures of Bell Brand Potato Chips in the Times Home Magazine and with the Bell-sponsored TV show Western Varieties on KTLA. Results have been not only in spread sales through most every city and town and small community in Southern California, but to make Bell Brand potato chips a "best seller" from San Diego in the south to Bakersfield and san Luis Obispo in the north (Properly managed potato chip plants reach in sales territory only so far as they can supply fresh products.)

Under the banner of Bell Brands, six other taste-tempting products are sold in ever-increasing quantities. "Frenchies" (shoestring potatoes), peanut butter, corn chips, pretzels, "Cheez Puffs," and Ruffles.

Quality knows no substitute and to insure that unvarying quality, Bell Brands maintains a laboratory and a chemist is in charge.

DEMOCRACY AT WORK

Only under our free American plan of industrial life can real democracy operate, and it is the belief of Cyril Nigg and his executive team that Bell Brands offers one of the best demonstrations of this activity.

Last February, a junior executive board of executives was created, consisting of ten members. All supervisory and administrative staff are eligible for selection to this board. A carefully planned system of of rotation ensures "new blood" for the board each year.

Regular meetings are held at which company policies are discussed and individual members submit new ideas for adoption. If any idea is unanimously voted for, after discussion, it is then submitted to president Nigg and the senior board. The senior board carefully considers it and then announces immediate adoption of the idea. or if not considered wise at the time a detailed report of the "reason why" is written and given the younger executives.

The junior board has already created enough sound and feasible ideas, adopted and now in practice to ensure the continuing success of this adventure in democracy. . . .representing the thoughts and activities and loyalties of the 250 Bell Brand employees.

"THE PLANT THAT POTATO CHIPS BUILT"

Bell Brand Foods Ltd. today is based in the big plant on Pacific Boulevard.

But the annual sale of much more than 15,000,000 pounds of potatoes . . . in the deliverable shape of many more millions of Bell Brand chips . . . has forced expansion into larger and up-to-the-minute headquarters.

Construction is now under way and will be completed the first of the coming year as a million-dollar plant.

The new plant will occupy eight acred of ground at Millergrove Drive and Los Nietos Boulevard, purchased a year ago. The main structure consists of precast concrete tilt-up walls supporting tapered steel girders.

The whole plant will be semi-automatic with five different systems of conveyors. A very important and modern detail is the fact that the entire floor will be steam-cleaned every day.

There is to be a dining room for employees with exterior terrace adjoining.

The great new headquarters truthfully could be "christened" "The Plant that bell Brand PotatoChips Built."

"IF IT'S BELL IT'S SWELL"

President, senior and junior boards are striving in every way to show Californians how Bell Brand Potato Chips are as desirable in DAILY enjoyment as are meat and vegetables and fruit.

More and more folks will learn the surprisingly large number of ways the crisp chips can supplement other units in the daily menu. Recipes are printed on the neat waxine packages.

By sustained perfection of quality, by controlled distribution, by brilliant advertising through newspapers, television and direct work, people are realizing that "If It's Bell It's Swell."

Bell Brand Snack Foods, Inc. was a Southern California-based manufacturer of snack products including potato chips, tortilla chips, and corn chips. The company's headquarters were located in Santa Fe Springs, California. The history of the company is continued by the nephew of Mr. Nigg, Tim Armstrong.

Cyril C. Nigg, who purchased Bell Brand from Max Ginsberg in 1947, was my uncle (mother's brother). My uncle Cyril sold the business to Sunshine Cracker in 1968, about 13 years after building the "Million Dollar Plant" in Santa Fe Springs. My father, Gene Armstrong, managed the distribution center in Loma Linda until we moved to Alhambra in 1950. Dad retired from Bell Brand in 1983 as the Plant Security Chief, following 36 years with the company. I left California for Alaska in 1975, my Dad passed away in 1994 and my uncle in 2000 (at age 95). I grew up around potato chips, peanut butter, Frenchies and corn chips, and have fond memories of everyone associated with Bell Brand.

G.F. Industries which also owned Sunshine Biscuits put Bell Brand up for sale in 1995 due to the company's financial issues. However, Bell Brand went out of business on July 7, 1995 after G.F. could not find a buyer for the company. Sunshine was sold to Keebler and then to Kellogg's. The only remnant of Bell Brand's product line left is Padrino tortilla chips which are still produced by Snyder's Lance Brands, which is now owned by Campbell's

View the photo of the bag of Bell Brand Potato Chips from the movie "The Seven year Itch" starring Marilyn Monroe.

See the Cecil and Beany (note the names are in reverse order) ad. It is followed by the Bell Brand logo.

See the back of the Sandy Koufax Bell Brand baseball card.

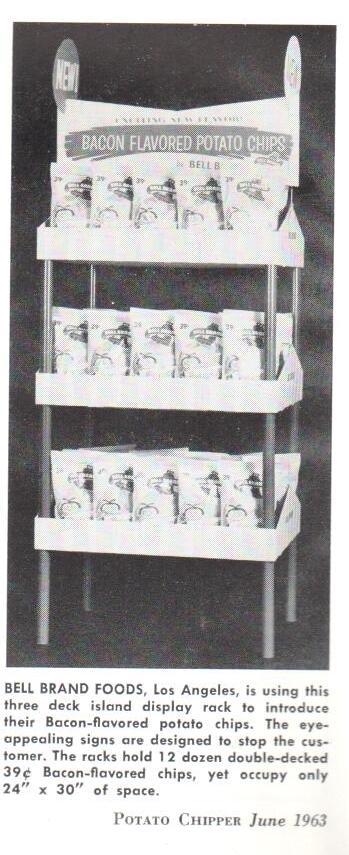

See also the bacon flavored potato chip stand photo from the June 1963 edition of the Potato Chipper

and the article about Cyril Nigg's retirement from the April 1970 edition of the Potato Chipper

. An article from the September 1953 edition of the Potato Chipper describes the new plant.

Enjoy the gallery of Bell Brand ads and the gallery of photos. View some 1950's Bell Brand grocery store displays.

http://mistertoast.blogspot.com/2006/03/bell-brand-potato-chips.html

. Finally see the photo of a woman and her child with a Bell Brand tin of potato chips and the photo of both sides of a bag of Bell Brand potato chips.

Enjoy the First Lady of Song, Ella Fitzgerald, sing the Gershwin classic, "Thou Swell."

youtube

The Toga Chip Guy

0 notes

Text

Should We Be Afraid of the Mariner East Pipeline?

City

The ongoing battle over the project is taking place in the backyards of Chester and Delaware county residents, who live in fear of a catastrophe.

Exton’s Paula Brandl and the Mariner East Pipeline construction barricade cutting through her backyard. Photograph by Shira Yudkoff

It was dark outside, around 5 a.m., when the flames took over the sky. Neighbors described it like this: a loud hissing noise. A massive ball of fire. A jet, or a meteor, crashing into the earth. Night turning into day.

On September 10, 2018, a section of the Revolution Pipeline — which had begun carrying natural gas just a week earlier — leaked and ignited in rural Beaver County, Pennsylvania, northwest of Pittsburgh. The rupture shot flames 150 feet into the air, destroying one house, collapsing several overhead power lines, and forcing the evacuation of nearly 50 residents.

Fortunately, no one was injured; the couple who lost their home had fled in the nick of time.

But for residents living along the thousands of miles of natural gas pipelines in Pennsylvania — second only to Texas as the nation’s largest producer of the fossil fuel and home to the newly booming, energy-rich Marcellus Shale region — the fire and the charred earth it left behind serve as a haunting reminder: Something like this could happen in our backyards.

That dread is perhaps nowhere more evident than 300 miles southeast of Beaver County, in the dense suburban neighborhoods west of Philadelphia, a city that energy industry leaders have, in the past decade, eyed as a global processing and trading hub. Here, tensions surrounding the cross-state Mariner East pipelines — a project much larger than Revolution and owned by the same parent company, Dallas-based Energy Transfer — are only intensifying.

The pipelines (Mariner East 1 and 2 and the not-yet-completed 2x) carry highly compressed natural gas liquids. Once they are fully operational along a 350-mile route from their Marcellus Shale source to a revitalized former oil refinery in Marcus Hook, they promise to be vastly lucrative for Energy Transfer — and for the state, which, the company boasts, could see an economic impact of more than $9 billion from the project. But since work began in February 2017, Mariner East has been plagued by nearly 100 state Department of Environmental Protection violations, multiple sinkholes, service shutdowns and construction chaos. Glaring gaps in state regulatory oversight have been exposed, and opposition has grown into significant pushback from neighbors and a bipartisan group of lawmakers who say Pennsylvania communities are at risk of — and unprepared for — a potential pipeline disaster.

Mariner East is headed for an inflection point: Construction could continue despite opponents’ pitched efforts, or officials could take steps to pause, end or remedy a project that’s been embattled since its inception. In the meantime, those at the heart of the Mariner East conflict zone live in fear of an incident like Beaver County’s — or worse.

•

In April, a fortress-like metal barricade was erected across the center of Paula Brandl’s quiet, grassy backyard in Exton, Chester County. The scene outside her kitchen window is almost dystopian. Brandl says land agents connected with Sunoco Pipeline LP, the Energy Transfer subsidiary that’s building the lines, told her the wall was installed as a noise barrier. For roughly two weeks after it went up, she says, she and her family members were “in shock.” Brandl contacted the agents and various state agencies to inquire about vibrations caused by the hidden construction as well as diesel exhaust in the air in and around her home, but she says no one she spoke with was helpful or informative.

“I have every right to know what is going on back there,” Brandl says at her dining room table one late-April day. “It’s just as if I don’t even own that land anymore.”

Energy Transfer is able to occupy Brandl’s backyard (and yards in 17 Pennsylvania counties) through what a recent New Yorker story termed a “legal loophole” linking the Mariner East project to the route of a 1930s pipeline that formerly transported heating oil. The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission, the main state agency tasked with overseeing oil and gas projects, has deemed the project a public utility, stressing that state code “recognizes the intrastate transportation by pipeline of petroleum products.” Doing so grants the pipelines right-of-way, which is typically reserved for utilities offering some sort of benefit to the general public, like schools or highways.

Energy Transfer spokesperson Lisa Dillinger says that putting additional pipelines into an existing right-of-way is a common practice that “helps to reduce our environmental footprint.” But the pipelines’ public utility status enrages Brandl and other residents, especially since a significant quantity of the product the lines carry is to be shipped overseas to make plastics.

“The PUC failed us,” Brandl says. “This is not a utility. This is not a gas line that’s serving the benefit of Pennsylvanians. And that’s basically the root of this entire issue.”

In Pennsylvania, there’s no state agency responsible for approving the routes of intrastate hazardous-liquid pipelines — nor does federal law require that oversight. David Hess, who served as Pennsylvania’s DEP secretary under Republican governors Tom Ridge and Mark Schweiker from 2001 to 2003, says the lack of any such authority puts Pennsylvania “in a very disadvantageous position … because the pipeline route is critical. If the law was different, I don’t think you’d ever approve a route through populated areas like these, given the risks with some of these materials being carried.”

Dillinger says that Energy Transfer goes “above and beyond what is required to ensure the safety of our lines.” But it’s clear that the state agencies left to regulate the massive Mariner East project — the Pennsylvania DEP and the PUC — have an unprecedented situation on their hands, with what Hess calls “unanticipated impacts” in areas “overgrown with development.” Chief among those impacts are sinkholes that have opened in yards along the pipeline construction route in Chester County, twice exposing the buried pipe of the 1930s line (now repurposed as Mariner East 1) and prompting pipeline shutdowns to avert what the PUC called a potentially “catastrophic” risk to public safety.

The residents who owned those once-quaint yards — on Lisa Drive, just outside Exton — said they were terrified for their lives. Then, in April, Energy Transfer bought two of the homes, and the families moved out. Now, the properties sit eerily quiet and mostly empty, save for construction equipment and a small sign in one of the yards: notice: audio and video recording in progress. When I visited the area in early May, a man who identified himself as a relative of one of the former homeowners told me that in the neighborhood, “Everybody wants to get out.”

•

Paula Brandl and other residents who have endured the complications of hosting Mariner East construction on or near their properties — water contamination, spills of drilling mud, intimidating contractors — say those side effects pale in comparison to their biggest fear: a pipeline leak.

Natural gas liquids can rapidly change to an explosive gaseous state during a leak, and the gas can be ignited by sources as small as static discharge from using a cell phone, flicking a light switch or ringing a doorbell. Leaks, which can be caused by welding failures, material defects, pipeline corrosion, shifting land and other factors, have already happened along Mariner East 1 — three since 2014, though none resulted in an explosion. Energy Transfer’s Dillinger says the 88-year-old pipeline underwent “integrity testing and major upgrades” when it was repurposed for natural gas liquids service, and in April, two years after a high-profile leak in Berks County, the company said it would conduct a “remaining life study” of the line.

Energy Transfer’s safety record is, however, bleak in general. Between 2002 and the end of 2017, pipelines affiliated with the company across the country experienced a leak or an accident every 11 days on average, according to an analysis of federal pipeline data compiled by environmental advocacy organizations Greenpeace USA and Waterkeeper Alliance. In an evaluation by NPR affiliate StateImpact Pennsylvania, the same federal data showed that Sunoco Pipeline is responsible for the industry’s second-highest number of incidents reported to inspectors over the past 12 years.

“When it comes to number of accidents, Sunoco’s not just an outlier; they’re sort of an extreme outlier,” Eric Friedman, a Delaware County resident who lives steps from the Mariner East pipeline route, tells me. Friedman, a former airline pilot who has worked for the FAA since 2006, sees Mariner East through a risk-management lens. (“Everything we do in commercial aviation is based on risk,” he says.) He learned of the pipelines in 2013 — a year after buying his home in an affluent Glen Mills neighborhood — and has been researching the project ever since. He’s in regular contact with the offices of lawmakers like U.S. Rep Mary Gay Scanlon and Chester County State Senator Andy Dinniman — the politician widely considered to be the pipelines’ most vocal opponent — and he’s one of the leaders of a nonpartisan residents group called the Middletown Coalition for Community Safety. In November 2018, seven residents of Chester and Delaware counties filed a complaint with the PUC against Sunoco Pipeline LP, alleging that the subsidiary hasn’t provided the public with a sufficient emergency notification system or management plan in the event of a pipeline-related disaster. The petitioners (nicknamed by residents the “Safety 7”) argue that as a public utility operator, Sunoco is tasked by federal regulations enforced by the PUC with providing an emergency-preparedness plan for potential disasters, like a possible leak along the Mariner East route. The failure to release a satisfactory plan, they say, places residents in the pipelines’ blast zone “at imminent risk of catastrophic and irreparable loss, including loss of life, serious injury to life, and damage to their homes and property.”

Energy Transfer has disputed the residents’ claims, saying that its emergency-response professionals “work and train with local first responders” and that it has shared a written public-education program specific to the area with emergency-response professionals along the line. Still, residents say the company hasn’t sufficiently involved the public in its preventative plans; the complaint is scheduled for hearings before an administrative law judge in July.

Meanwhile, the PUC has said it won’t release information about the potential impact of a leak or an explosion for several reasons, including that the state’s Right to Know law prohibits the disclosure of records that are “reasonably likely to jeopardize or threaten public safety.” Sharing the hazard assessments, the PUC argues, could compromise pipeline security by revealing information “which could clearly be used by a terrorist to plan an attack … to cause the greatest possible harm and mass destruction to the public living near such facilities.”

Brandl and other residents stress that living next to a “mass destruction” target is terrifying, with or without a disaster plan. To make matters worse, a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found major weaknesses in how the Department of Homeland Security’s Transportation Security Administration — which is responsible for addressing terrorism risks along the nation’s 2.7 million miles of oil and gas pipelines — manages its pipeline security efforts.

“I don’t think I’d be living 25 feet away from that pipeline,” Hess, the former DEP secretary, says. “But again, the question is, why was someone allowed to live within 25 feet of this pipeline in the first place?”

•

In December, Chester County District Attorney Tom Hogan announced a criminal investigation into conduct related to the Mariner East project, saying that potential charges against individual Energy Transfer employees or corporate officers could include causing or risking a catastrophe, criminal mischief and environmental crimes. More recently, Delaware County DA Katayoun Copeland and Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro launched a joint investigation into Sunoco Pipeline LP and Energy Transfer over allegations of criminal misconduct related to the project, with Copeland stating that there “is no question that the pipeline poses certain concerns and risks to our residents.” (At press time, both investigations were ongoing.) Energy Transfer’s Dillinger says that the company remains “confident that we have not acted to violate any criminal laws in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and are committed to aggressively defending ourselves.”

After years of pressure, residents might finally be getting through to the state. At a Pennsylvania Senate committee meeting in June 2018 — before, even, a number of critical developments regarding Mariner East — former Republican State Senator Don White of Indiana County made a surprising statement: If issues raised at the committee’s meetings regarding pipeline safety consistently involve one project — referring to Mariner East — then “we have the ability in this state to find a way to deal with this company and put them out of business.”

David Hess, the former Republican DEP secretary — he was also executive director of the state Senate Environmental Resources and Energy Committee in the ’90s — says that for a “Republican senator to say that is astounding … [it] really underscores the problems this company is generating.”

As frustration and fear about Mariner East spread to constituents in red and blue districts alike, lawmakers who are typically supportive of the oil and gas industry (like north-central Pennsylvania State Senator Gene Yaw) are voicing concern. White’s proposition poses a question that residents are forcing officials — particularly Governor Tom Wolf, who has positioned himself as an ally to environmentalists and residents but has received tens of thousands of dollars in donations from oil and gas industry affiliates — to consider: How should they deal with the Mariner East pipelines?

Several months after the Revolution Pipeline incident in Beaver County, Wolf released a statement calling on state lawmakers to “address gaps in existing law which have tied the hands of the executive and independent agencies charged with protecting public health, safety and the environment.” His suggestions included giving the PUC authority over the routing of intrastate pipelines, ordering companies to work with local emergency coordinators, and requiring the installation of remote shutoff valves to contain leaks. But the GOP-dominated legislature has yet to move any bills that would allow for those reforms. And none of that changes the fact that Mariner East has been unfolding on Wolf’s watch. The Governor has yet to visit Delaware or Chester counties to speak firsthand with residents living near the pipelines about their experiences. (Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman visited before the 2018 primary; a spokesman for Wolf’s office said the Governor has met with residents and lawmakers about the project in Harrisburg.) Constituents say Wolf is simply not doing enough to prevent a potential disaster. Whether his administration will adopt a firmer stance toward Mariner East — as residents and local lawmakers have requested — remains uncertain.

Meanwhile, the project continues to highlight the limitations of both the DEP and the PUC. After all, there were warning signs before the Beaver County leak, which Energy Transfer has said resulted from a landslide that followed heavy rains. (Both the company and the PUC are still investigating the incident.) The DEP had fined Energy Transfer three months before the Revolution Pipeline explosion for failing to mitigate erosion on a hillside about a mile from the site; the DEP says that at the time, it was “unaware of the issues associated with the blast site.” Critics have also questioned the agency’s decision to allow Sunoco Pipeline to use relatively new and potentially disruptive drilling methods that geologists say may have increased the risk of sinkholes along Lisa Drive in Chester County. The PUC and state DEP have penalized Energy Transfer for many of the company’s missteps, at times (and increasingly) seriously. Revolution Pipeline remains out of service, and since February, the DEP has suspended all Energy Transfer permit applications (including for Mariner East) until the company reaches compliance in Beaver County. To Hess, the agencies are “working in the best way they can.” But, he argues, lawmakers need to consider more stringent regulation, especially of pipeline routes.

The question for residents is whether officials or Energy Transfer will act before an emergency. Until then, Eric Friedman says, they’ll continue to feel unprotected.

“I think at some level, the most important function of government is to reasonably provide for the public’s safety,” he says. “And how can you have a project like this, that could kill hundreds or thousands of people in the worst-case scenario, and hope for the best and not plan for the worst?”

Published as “What Lies Beneath” in the July 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Source: https://www.phillymag.com/news/2019/07/06/mariner-east-pipeline-sunoco-pennsylvania/

0 notes

Text

Discovery: Thien Venus Milo

With her very first collection, couture designer Thien To distinguishes herself as a talented artisan who’s bound for big things.

PHOTO BY MIKHAIL VETER

The striking artistry and original vision of twenty-four-year-old Thien To, who makes clothes under the name Thien Venus Milo, mark her as a designer to watch. For her senior collection at Philadelphia's Drexel University this past June, the first-time designer presented seven edgy, intricate, and opulent couture looks in silk, satin, leather, and tulle, inspired by the story of Alice in Wonderland. Molding laser-cut plexiglass forms into leather and incorporating patterns used in welded iron railings into her red, white, and black designs, To created an imaginative eveningwear collection with ornate details. "My inspiration comes from my fantasy but also from my turmoil," says To, who emigrated to the U.S. from Vietnam six years ago. "A lot of people don't understand me, and I went through a lot of depression until I actually brought this collection to life." She points to where serpentine black designs meet pale tulle on one outfit. "The black represents one of my down times. Depression was eating up my energy. The part in black leather is taking over my body." For To, making clothes is not just a trade or an art form, it's also therapy. She credits the avant-garde designer Alexander McQueen for getting her interested in fashion. "McQueen said he wanted women to be scary. He wanted women to be powerful," To explains. "I don't really want women to be scary as much as I want them to be respected."

For her presentation, To cast her models in dramatic roles, as queens, princesses, and warriors, in part because she sees clothes as potentially transformative: Costumes can protect, empower, and embolden the wearer. "I have a lot of corsets in my collection because I believe when a woman wears a corset she always stands straight," she says. "Up straight is a powerful pose. People say that corsets manipulate the body. If a corset is done right, it gives the woman the power." The collection is memorable not only because of its blatant embrace of fantasy and its simple three-color palette, but also because of the story it seems to tell. It evokes the pleasure and the torment of growing up, with each look in the collection conjuring a specific moment in a girl's transformation into an adult. The way that designs and cutout motifs repeat and subtly evolve from the beginning to the end of the collection indicates the erratic progression involved in coming of age. There's a fanciful juvenile period shown, for example, by a single red leather sleeve with red hearts and flower-pattern cutouts atop a white high-low gown. Throes of crisis are exemplified by a woman warrior in flouncy white sleeves, a tight black leather corset top, and black leather pants. Newfound self-assurance is embodied first by a model in a womanly red leather corset and voluminous white satin skirt over a tulle petticoat, and then by the most theatrical—and elaborate—look in the collection, an imperial queen in a black leather and organza corset-like top with filigreed leather bands sinuously winding over the top of a floor-length satin skirt that had been overlaid with charcoal-grey tulle. Her final piece is an off-the shoulder bridal minidress in white, with a long crinoline overskirt. "In Vietnam," she explains, "there is a village where women do incredible embroidery. When a woman wants to work in that field, she first has to be an apprentice, and then she has to be initiated into that career. When she is initiated, she has to make two dresses—a life dress and a death dress. The life dress is what she's going to wear at her wedding. And the death dress is what she's going to wear at her funeral." "This is my life dress," she says, pointing to the wedding dress that ended the show. "And this is my death dress," she says, pointing to the black and white dress of her most forbidding queen. As a child in Ho Chi Minh City, To enjoyed drawing, but was also interested in math and engineering, thinking perhaps she would become a doctor. The transition of moving to the States, where she chose to go back to high school at eighteen, in part to improve her English, was hard. While helping with costume design for a play her school was doing with the Philadelphia Young Playwrights, To was struck by how costumes seemed to influence the wearer's personality. "At that time, I did not want anybody that I ran into to know that I was depressed, so my goal at that moment was to find a way to help people stay happy with whatever their situation is," she says. She found solace when she resumed making the manga-style drawings she had begun in her earlier years, this time using the style for fashion illustration. Her choice to study fashion design was a surprise to those around her, but her realization of how clothes can affect a person seemed both significant and practical. "Sometimes what a person wears can touch their emotions a bit," she says. "I know I can make my work meaningful to people." For now, To is open to limited commissions because of her day job as a technical designer. She is adventurous in spirit and audacious in the design of sensuous forms. But To offers a pragmatic takeaway when it comes to what she's learned by growing up: "People need to share their thoughts on beauty, fantasy, and art every day."

—Julia Yepes

October 7, 2016

0 notes

Text

Welding technicians need to have a blend of basic understanding and advanced skills to stay ahead in the competitive welding market in 2025.

#welding certification courses in philadelphia#welding course for beginners in philadelphia#welding training courses in philadelphia#professional welding courses in philadelphia#welding trade school requirements in philadelphia#welding technology course in philadelphia#Advanced welding courses in philadelphia#Welding certification training in philadelphia#advanced welding certificate in philadelphia#Specialized welding training in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

youtube

What does the future hold for aspiring welders at Philadelphia Technician Training Institute? In this unique and emotional video, experience a creative messaging exchange between PTTI and thirteen welding students discussing their dreams and ambitions after graduation. From aspiring entrepreneurs who dream of owning their own welding businesses to those aiming to work in shipyards and major industries, this video captures the diverse aspirations of our students. Each message reveals a personal and heartfelt ambition, showcasing the boundless opportunities that PTTI's welding program opens up for its graduates. Join us as we delve into the hopes and dreams of these future welding professionals, illustrating not just the skills they acquire at PTTI but also the personal motivations that drive them. Whether they envision creating art with metal or building the structures of tomorrow, every student's ambition is a story of potential waiting to be unleashed. Watch now and be inspired by the powerful ambitions of PTTI’s welding students. Their dreams are big, their potential limitless, and with PTTI, all doors are open. Visit https://ptt.edu/ to know more

#welding trade programs in Allegheny West#welding technology school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#fabrication welding training in philadelphia#welding certification training in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding training school in Philadelphia#welder training in philadelphia#welding trade schools degree in philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

To become a welder in 2025, one needs to have their basics clear. Trade schools help technicians gain theoretical and practical experience.

#welding trade programs in Allegheny West#welding technology school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#fabrication welding training in philadelphia#welding certification training in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding training school in Philadelphia#welder training in philadelphia#welding trade schools degree in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

youtube

See our talented students mastering the art of welding at Philadelphia Technician Training Institute! Discover how our hands-on training equips them with the skills needed for a thriving career in the welding industry. At PTTI, we blend expert knowledge with practical experience to give our students a leading edge in the field.

#welding trade programs in Allegheny West#welding technology school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#fabrication welding training in philadelphia#welding certification training in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding training school in Philadelphia#welder training in philadelphia#welding trade schools degree in philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Explore top-notch welding training programs and courses designed to equip you with essential skills. From MIG to TIG welding, our programs offer hands-on experience and certifications to kickstart your welding career. Whether you're a beginner or an experienced professional, find tailored options that fit your goals. Philadelphia’s local welding schools provide expert-led instruction, modern equipment, and practical training opportunities. Start

#welding trade programs in Allegheny West#welding technology school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#fabrication welding training in philadelphia#welding certification training in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding training school in Philadelphia#welder training in philadelphia#welding trade schools degree in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

Where Can Training Take You In 2025: Craft A Career In Welding

A career in welding offers opportunities with great earning potential. Read more about the prospects of jobs in welding in 2025.

#welding trade programs in Allegheny West#welding technology school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#fabrication welding training in philadelphia#welding certification training in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding training school in Philadelphia#welder training in philadelphia#welding trade schools degree in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

youtube

Meet Jinay Frazier, a proud graduate of the Welding Program at Philadelphia Technician Training Institute who transformed her life through hard work, determination, and skilled trade training. In this powerful alumni spotlight, Jinay shares her inspiring journey of overcoming personal challenges, including navigating the harsh realities of gun violence in her family and community.

#welding vocational school#welding job in Philadelphia#welding course in Spring garden#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#welding course in north philadelphia#welding certification training Institute in Carroll Park#welding certification training Institute in south philadelphia east#welding certification training Institute in north philadelphia east#Welding Trade Programs in south philadelphia#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Watch our skilled students in action as they perfect the art of welding at Philadelphia Technician Training Institute! Look at the hands-on training that prepares them for a successful career in the trade. At PTTI, we combine knowledge and practical experience to give our students a competitive edge in the field of welding.

#welding vocational school#welding job in Philadelphia#welding course in Spring garden#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#welding course in north philadelphia#welding certification training Institute in Carroll Park#welding certification training Institute in south philadelphia east#Welding Trade Programs in south philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Do You Need A Degree To Become A Welder?

To become a welder one has to be technically proficient and have some basic welding understanding. Read more how one can gain these skills.

#welding vocational school#welding job in Philadelphia#welding course in Spring garden#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#welding course in north philadelphia#welding certification training Institute in Carroll Park#welding certification training Institute in south philadelphia east#welding certification training Institute in north philadelphia east#Welding Trade Programs in south philadelphia

0 notes

Text

What Is Shielded Metal Arc Welding? How To Become An SMAW Technician

How to become a SMAW technician, and get welding education at leading welding tech schools in Philadelphia

#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welding trade school in South West Philadelphia#welding course in philadelphia#welding certification training Institute South West Philadelphia#best welding trade schools in philadelphia#welding tech institute in philadelphia#welding trade program institute in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

Incorporating Soft Skills In Welding Technicians Training

Interpersonal skills are as important as practical knowledge in the welding sector. Read more to know the importance of soft skills in welding technicians training.

#welding trade School in Carroll Park#welding certification training Institute in south philadelphia#Welding Trade Programs in south philadelphia east#welding course in south philadelphia west#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding trade school in South West Philadelphia

0 notes