#We talked about Native Americans/Indigenous People every single year since I started Public School. I checked out a good amount of books.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Also just to further complicate this debate. In much of the Western U.S., a Scone is pretty much Fry Bread, Sopapillas or Beignets and is the base for a Navajo Taco. (Again called in that case called Fry Bread because that is what Indigenous Americans call it. For them it came out of their cleverness in using the particularly insufficient Government rations they received when they were forced onto barren reservation lands.)

Depending on where in the Western U.S; it is traditionally served with honey and butter, at least when the particular recipe comes from White Americans that have been in the Western U.S. for 3 generations or so, sometimes Jam. Sopapillas have their own particular way of being served, (honey, and syrup; or savory) and sometimes dramatic differences in recipes; those come from Latin America. Beignets I'll admit to knowing almost nothing about them, a part from the Princess and the Frog; usually with powdered (confectioner's) sugar.

Obviously the nearer you are to a Rez, the more likely it will be called Fry Bread. Whereas if you're in a white former frontier/pioneer land it's probably called Scones and if you're in a Latino Heavy place in the West... Sopapillas it will be. Having never made it to the American South, I can't say how common Beignets are... it's possible it's just a Former French Colony thing, I know Fry Bread also happened there... but it's possible that's partly the influence of the Reservation System.

A lot of cultural exchange happened between even Faraway Indigenous Nations because of how necessary supporting each other was in trying to keep the American Government from decimating them. (Both regular genocide and cultural genocide wise. Because the U.S. definitely are colonists in the worst kind of way and learned Imperialism as an M.O. from the Brits.) But from my understanding Fry Bread has been claimed to be from the Navajo. (But I also live in a Navajo corner of the nation... so... It's also possibly the case of Simultaneous Invention. )

But yeah, Look up California Scones or Utah Scones if you want to see those. Sopapilla to see those and Fry Bread too. Scones/Fry Bread may be square or they may be free form blobs. I learned to make them freeform but they were temporarily commercialized with SconeCutters and were square then. From my understanding Sconecutters as a restaurant is no more. You could get them with Chili Cheese, honey butter or as a subway like Sandwich from there. Now for rising base, there's some debate about whether they're traditional Scones with yeast, without yeast or with baking soda. I learned to make them with Yeast. They are always deep fried though and turned over when one side is done.

I was around 20 years old the first time I ordered a scone at a restaurant and was given something that looks like the example of the American Scone. Every other time I got Fry Bread. (And I loved Scones/Fry Bread... so plenty of ordering ;)) I'd lived in the Western U.S. my entire life at that point and was 4-5 generations (depending on the family side) there. Funnily enough I thought it must have been an English Scone. Until it kept happening at various Cafes when I traveled.

settling a debate, reblog for reach

#American Scones#Utah Scones#Fry Bread#British Biscuits#American Biscuits#British Scones#Debate#Now I ask them to describe what a Scone is before ordering it at a restaurant.#Because sometimes you want Fry Bread and sometimes you want a Pastry and sometimes you want that fruitcake like thing.#Polls#They're very very much not the same thing#Western U.S. History#Brief mention of Indigenous Genocide#Brief mention of Indigenous Cultural Genocide#The Reservation System in the U.S.#Native Sovereignty#The poor government rations were legit meant to starve out the Native Americans/Indigenous People.#But make it look like it was an act of God or accidental. The U.S. Government tried so many times to literally kill the Native Americans#Indigenous People of the U.S. so many times. And it is a testament to their amazing communities that they made it through to today.#They deserve better and you literally cannot look at any part of American History without seeing the scars left there.#And on top of it many Nations preserved their histories their languages their handicrafts and culture despite literally being killed#and tortured for any indication that they knew any of it. We stole and sold their children in attempts to take them out.#And we keep breaking our Treaties with them. We need to do better. In the Dakotas they've removed Tribal ID as acceptable ID for voting.#Which was completely purposeful. And obvious retaliation for the Pipeline Water Defenders.#(I am not Native/Indigenous and so I can't speak for all their issues nor do I know them. I've done my best to educate myself#and I will continue to share information that I do know. But the amount of history that's just ignored because it puts us in a bad light.#It's so much it's insane. And despite knowing Native People practically my whole life. I had no idea how much I didn't know 'til College.)#We talked about Native Americans/Indigenous People every single year since I started Public School. I checked out a good amount of books.#I wrongly believed I had a good grasp of how many atrocities the American Government had/was committing.

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

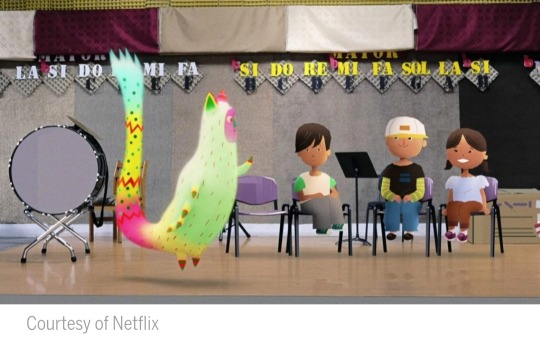

Created by Elizabeth Ito, the animated series City of Ghosts explores the history of different neighborhoods in Los Angeles through friendly ghosts that make the past of this metropolis real. Our guides into these adventures, created in documentary style, are a diverse group of children, the Ghost Club, who navigate each encounter with curiosity and compassion.

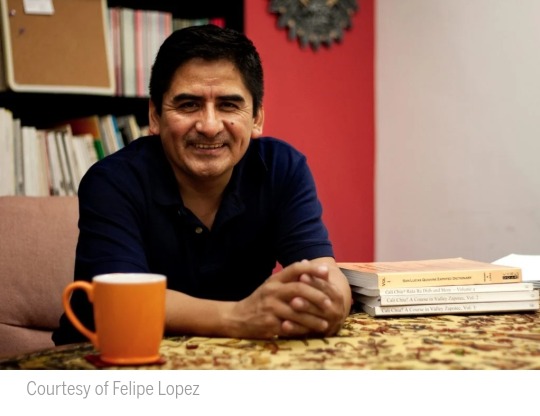

For episode six, focused on Koreatown, the creators recruited professor Felipe H. Lopez, a Zapotec scholar to help them portray the Oaxacan community of L.A. With Ito and producer Joanne Shen’s support, Lopez brought authenticity to the depiction of certain visual elements, such as the grecas de Mitla, geometrical designs specific to the Indigenous people of Oaxaca. More importantly, he voices an animated version of himself, as well as Chepe, a lovable alebrije ghost at the center of the story. Lopez’s dialogue is both in English and Zapotec.

A native of the small Oaxacan community of San Lucas Quiaviní, where the vast majority of the population speaks Zapotec, Lopez has become a binational bastion in the preservation of this Indigenous language and the culture it gives voice to. He came to the United States when he was 16 years old speaking mostly Zapotec. He learned English first and then he worked on improving his Spanish while at Santa Monica Community College.

In 1992, Lopez got accepted into University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in the Latin American studies program; he has restlessly devoted himself to preserving the identity of the Zapotec diaspora, which has been present in the United States since the days of the Bracero program. Lopez first found support in linguist Pamela Monroe with whom he created the first trilingual Zapotec dictionary, which was published in 1999 via the Chicano studies department at UCLA. Today he is a postdoctoral scholar at Haverford College.

Below, he expands on his life’s work and the significance of the positive mainstream representation of Indigenous peoples.

What was the impulse or situation that made you realize you wanted to dedicate your professional life to preserve the Zapotec language and culture?

There’s always this relationship between economic gains with language. I saw how a lot of families in the Oaxacan community were raising their kids. Even if they didn’t speak Spanish fluently, they wanted to teach their kids Spanish rather than Zapotec. In a sense, they didn’t see a lot of usefulness in teaching their kids Zapotec. Interestingly, some of them actually were teaching their children the little English they knew. They even skipped teaching them Spanish. The parents would speak with each other in Zapotec but then would talk to the kids in English.

Being a college student back then and thinking about those things made me realize that the language was being lost and being substituted by either Spanish or English. At that moment I thought, ‘Maybe my language is going to be lost. I’ve got to do something about it. Even if it is just to leave a record. I want it to at least be known that we spoke this language at one time.’ That’s what really drove me to seek out somebody to help me because I’m not a linguist. Ever since then, we’ve been creating a lot of open source materials in Zapotec for people to use. We now have dictionaries. We’ve really used the technology in order to make our language, our culture, and how we are visible. City of Ghosts is another component that continues the work we started in 1992.

One of the interesting things about Indigenous languages is that sometimes they are not seen as real languages. You have this battle against the established ideology that Indigenous languages are not really languages. It’s almost like being salmon going against the current, if you’re trying to preserve your language because there are very few spaces for you to use your language and it’s not being taught in public schools in Mexico. But I was fortunate to be able to teach one of the very first courses in Zapotec. In 2005, UCSD [University of California, San Diego] asked me to teach a course in Zapotec. We needed to create all the materials from scratch because unlike Spanish or English or French, which are the dominant languages, you have tons of materials. If you want to teach Spanish you can go to the library and you have tons of materials to teach. But for us as Indigenous teachers we really need to create materials.

Language is deeply connected to how a culture sees the world. In that regard, why do you think it’s necessary to protect and teach Zapotec and other Indigenous languages in Mexico?

A lot of our Indigenous knowledge is embedded in the language. For example, when I think about how we’re being taught math in school from a Western point of view, we have the decimal system of counting: 10, 20, so on. But in Zapotec we have a different counting system, which is a base 20. We do 20, 40, and 80. Sadly, in Mexico something people say, ‘Why do you want to preserve the language? It’s not even a language. It’s a dialect.’

Fortunately, last year, I think if I’m not mistaken, Mexico changed the constitution to recognize more than 68 languages spoken in Mexico as national languages. There has been a long struggle. I’ve been doing work both in the U.S. and Mexico. Currently I’m teaching a free course on Zapotec in one of the universities in Mexico, because I want to contribute. Indigenous languages are important because they represent our history. They represent our identity and the ways in which we see our surroundings. There are even words in Zapotec that I can’t even translate into Spanish because there are no concepts that are equivalent. They need to be explained.

With the constitutional changes that you mention and someone like actress Yalitza Aparicio inspiring conversations about racism in Mexico and across Latin America, do you believe we are on the brink of a deeper appreciation of Indigenous culture and language?

It’s interesting that you mentioned Yalitza because when she first came out people attacked her. They would say, ‘She’s an Indian. She doesn’t deserve to be there.’ It is the sentiment that has endured in Mexico and Latin America. It’s a colonial mentality. If you look at the soap operas and Mexican TV shows just about every single actor or actress is white. There has been a push historically for Mexico to aspire, to be white. We, as Indigenous people, have been perceived to be a problem for modernity. They feel like, ‘How can Indigenous people be modern?’

We tend to be very fluid and move into different cultures, into different eras. I can speak my language in my pueblo, but at the same time I can use the Internet and I can speak English.Being Indigenous is never a detriment.In Mexico, the dominant culture, the politicians and the [non-Indigneous] intellectuals, see us as something less than Mexican. They speak about Mexicans versus Indigenous people. I’ve always questioned that because they like to talk about Mexico’s Indigenous roots, yet ostracize and put us on the margin. When they speak about Indigenous communities, they tend to think of us in a museum because once you put us in a museum it means that we no longer exist. There is this contradiction in terms of where we are, where we fit in Mexican society. That’s why we’re pushing so hard to make ourselves visible.

Specifically speaking about Zapotec people, and other immigrants from Indigenous communities, in the United States, what are the major obstacles in resettling?

Indigenous immigrants go through two steps of assimilation, because a lot of us who move into the States, we bring our indigenous language and culture. But the dominant culture that exists in LA is a Mexican or Mexican American culture. It’s a mestizo culture and there’s Spanish. So we as Indigenous people first need to assimilate into that culture and then assimilate into the mainstream culture. We need to speak English, but we also need to speak Spanish. There are two steps of assimilation for us to even try to situate ourselves in mainstream American society.

Tell me about your experience working on such a unique show as City of Ghosts, which really digs deep into the cultural fabric of Los Angeles. What convinced you that this could be positive for Indigenous communities?

One of the things that I asked Joanne [Shen] was, ‘How much say do I have?’ Because I didn’t want to be there if they already had an idea and they just want me to emulate something. So she said, “No, we want to sit down with you and talk about what are some of the important aspects of Zapotec society and what is it that really impacts you guys? How do you see the world?” That was one of the most important things for me in order to agree to do the project.

We had several meetings in terms where they asked me questions. Once I looked at the whole script, not just mine but also those for the alebrije ghost Chepe and Lena who is voiced by Gala Porras-Kim, I made some changes according to how I felt it represented Zapotec culture. For example, tying the idea of the ghost with the idea of the nahual orthe alter ego in Zapotec and Mesoamerican culture, as well as the use of alebrijes and the colors, which properly represented Zapotec culture on the screen.

They were very sensitive and they wanted to get it right. I really commend them for that, because I’ve worked in projects where they don’t really care. They have an agenda. But for this project they were so attuned with me.I think that’s what makes City of Ghosts such an important program for kids and just for the public at large to understand who the Zapotec are, because when we think about the Mexican community we assume that everybody speaks Spanish. This program, and specifically episode six, will help people to at least begin to rethink Mexican society and that not all Mexicans speak Spanish. Not all of them are mestizo, but rather that we are a multilingual and multicultural society, and we are bringing that to the States. I hope it makes people at least curious.

One aspect prominently mentioned in your episode is how certain Oaxacan communities use a whistling language. Why was this a significant element?

To be honest with you, I have no idea where it came from, but as far back as I remember when I was a kid we would just whistle to communicate basic phrases to each other. Also when we go to work on the field and you see somebody far away, you whistle at that person just to get some information like, ‘How are you doing? What’s going on?’ Since, we didn’t have any phones back home then, we whistled to communicate, but it’s not entirely just Zapotec communities. There are other Indigenous communities in Oaxaca and Mesoamerica that use whistling as a means of communication. So when I was asked to be part of the show, I did a lot of whistling in the episode just demonstrating how we communicate and that we don’t need words. Whistling is another expression of language.

When you think about Angelenos you think about Mexicans or mestizos at the pueblo of Los Angeles. But we rarely talk about the Indigenous people in LA. By having the Zapotec people in this sho2, we begin to have this conversation go beyond thinking about this land only having Latinos, African Americans, and whites. There are these hidden multicultural societies here that have been fighting and resisting against all these forces.

One thing that is so interesting to me is that when we are on the margins, we tend to fight and resist at the margin to maintain our language and culture. So then by bringing us into the light and being visible, even by asking, ‘Where do you guys come from?’ We can say, ‘Well, we’ve been here all along. You just haven’t seen us.’ With these particular episodes on the Zapotec, all of a sudden some people might learn something. I’ve seen on Twitter the young Indigenous people express they feel so proud of the fact that Indigenous people are represented in this show. There’s something unique about this show, because it really brings some of the historical aspects of the composition of LA, specifically of the Pico-Union area.

The most important thing people should take out of those two episodes that talk about Indigenous communities, it’s the very first time that we see Indigenous communities well represented and not objectified, but just as human and what they do in everyday life. And also how we bring our traditions and cultures to some of the megacities in the world, coming from small communities, such as mine where we have about 1700 people, yet we are being represented in such an incredible episode.

City of Ghosts is streaming on Netflix.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Mothering a Foreigner

When my daughter was younger, we went for a pram ride one given Sunday. A woman passed by, walking her dog. I stopped, went on my knees, pointed to the doggie and said: “Look! Au-au!”. My baby looked at the dog, with the excitement only kids have and said: “Woof-woof!”. Perhaps a small detail to some, but I remember my astonishment and sadness when I heard that. That is not how dogs bark to me. I have not lived in my native Brazil for almost a decade and honestly, to this date, I cannot hear a “woof-woof”, no matter how hard I try. My eardrums just vibrate a crystal clear “au-au”, every single time. She did not learn that from me, but from others. It struck me like a lightning: I am mothering a foreigner.

I am not in the slightest nostalgic, left alone patriotic, but that made me realise how very little childhood references my daughter and I share. For instance, I do not know virtually any nursery rhyme she sings. I mean, why are the three blind mice running? But then, equally, how to explain why the carnation fought the rose under a balcony? She does not recreate the indigenous legend of the cassava or of the Amazon dolphin at school, and, chances are, she will never really see any of them in her lifetime. Maybe much later: I saw a squirrel for the first time when I was 15; she runs into them every morning in our garden. She spat, disgusted, feijoada when I tried to offer; I have eaten it pretty much weekly growing up. I felt victorious I could influence on her liking of Turma da Monica as opposed to Cloudbabies, but do not know if this small victory will last until Reception. Talking about Reception…Grammar School, sixth form, GCSE, A-levels? I flip nervously through all brochures, trying to trace parallels in my mind with the education system I did attend. In her “Ser mãe de gringo”, author Liliana Carneiro (@li.carneiro) list a multitude of differences between her upbringing in Brazil and, now as an expat, her daughter’s: Mother’s Days are celebrated in different dates, while Grandparent’s Day don’t have any equivalent up here; she does not know if it is acceptable or creepy to invite kids over for playdates. She insists on celebrating Carnival Tuesday when everyone else is doing a way (waaaaay) less exciting Pancakes Day. She struggles to pronounce her daughter’s surname, just like I do! The list goes on.

Motherhood, by default, brings along countless internal conflicts. For me, this experience has been topped up with a whole bunch of other challenges. She will have to brush her teeth again at noon and will never have a birthday party before the actual birthday. She will always have a prayer next to her bed to prevent the evil eye - as she will have rue branches behind her door to prevent evil eye (ok, maybe Brazilians are a bit too obsessed with evil eyes!). I will watch her hockey games but will probably not have a clue if she is good or not, so little I get about the sport’s rules. I will do my best to help homework, from correct spellings to solve algebra problems, in a different language. I will challenge the Imperialist approach of her History books but might hear a “No, mummy, that’s not how WE tell the story here!” back. I often hear I am short-fused even when I think I am just being assertive! I am frequently tempted to nickname people immediately. In Brazil, if you meet a Camila, you instantly start calling her Ca, Camilinha, Mila, Caca etc.. Whatever you decide and you can change it anytime. In the UK, you must wait for coordinates: “I am Camilla, but I go by Milla”. It blows my mind you get to decide your own nickname! Or that you do not give a lengthy hug (pandemic aside) and invite someone you just met over for a BBQ when you literally have no food in the fridge. “Just come, we will sort it out!”, I grew up saying. Not anymore. They may all sound like small details, but they considerably change how you connect with people and express affection.

I have read the beautiful and delicate “My mom is a foreigner – but not to me”, by the American actress and author Julianne Moore. About the experience of being raised by a nonnational, she said on an interview: “My mother was from Scotland. I could not hear it, but she had an accent. When I was little and I would bring people home, they would say ‘why does your mum talk so funny?’. I would of course get really infuriated and embarrassed!”. Well, the thought of it is scary, isn’t it? I do not mind coming across as an alien to anyone else (“don’t care, no one pays my bills!” – the classic Brazilian proverb!). I nonetheless care about being a source of embarrassment to my daughter, just for being an outlander.

Just very recently, I have found out the November 5th bonfires celebrate the FAILURE of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Well, I come from a country positioned among the Top-100 countries in Corruption Index (Transparency International). A country that was exploited and subjugated by European Crowns since the 15th century; a country that suffered a coup d’état, instigated by the Americans and supported by some of its own MPs, agonising a two-decade long military dictatorship. I simply assumed we celebrated someone dared to try to explode a Parliament! I obviously now see how absurd that is. My background accidentally made me take Guy Fawkes for a martyr, not a villain. This is just one of many examples. Daily, I choose to give up my cultural capital to adhere to the mindset of the place I decided to call home. Yes, it was a decision, and yes, I review it from time to time. But anyhow, these cultural differences shape my motherhood exercising in numerous ways.

Language is possibly the most noticeable point. It is through orality that the identity of a people is shown more strongly. Quoting Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) “My motherland is my mother tongue”. The controversial Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (1929) suggests the structure of a language affects its speakers' cognition and shape their perception of reality. For instance, if you speak a Latin language (Portuguese, Spanish, French etc), you must categorise people in terms of social dimensions (to pick a “tu” or a “vous”); German does not have present participle (-ing), so German speakers tend to focus on beginnings, middles or ends rather than in the action. Another fascinating aspect of language is the link between bilingualism and personality. Studies found that, when switching languages, people may also switch their way of thinking to “fit” the language. In the 00’s, linguists Dewaele and Pavlenko asked hundreds of bilinguals if they felt like a different person when they spoke different languages. Nearly two-thirds said they did. The connection between language and identity is, as it seems, context-based, malleable and impermanent.

Moreover, language is the element that enables bond between generations and facilitates the transfer of the cultural heritage within members of a community. All my primary fond memories are in Portuguese. This is the language my grandfather told me tales, that I heard the jokes I found funny, that I wrote my first love letter and my journal, in teen years; that I had my first arguments, learned how to negotiate and weigh in decisions. And if we agree we are the result of our laughter, loves and struggles, then a huge part of who I am comes from experiencing life in my native tongue. I am less articulated in any other language; will I be able to advocate for my daughter clearly if she has problems at school? At the same time, I give her endless cafunes, when I am breastfeeding; I say I was dying of saudades when she comes from nursery. I look for her favourite teddies repeating “Quede?”, to which she opens her little arms in the air with a rhetorical “Where?”. All words that really do not have a perfect translation in English. Their meanings are profoundly connected to someplace else.

On his book “Raising Girls”, Biddulph provoked me to think long and hard about how my relationships with men are, how I make friends, how I keep promises and, more importantly - what are my core values. Does my daughter clearly know what I stand for? Arguably, he says, she will learn all these things from me. And then my oh-always-so-worried mind takes a pause and focus on what really matters. And truly hope that my accent, huge earrings, tattoos and constant “PDAs” (“public display of affection”) will not be a source of awkwardness but else a celebration of her own ancestry. Just a gentle continuation of a lineage of women that started somewhere is distant times, found its way among pain and joy through Portugal and Brazil and is now completing yet another honourable leg in English lands. May I be blessed, with the time and the wisdom, with the chance to help her navigate all the seas her DNA can offer.

And if things get hard, I shall read to my little gringa the poem, “lands,” by Nayyirah Waheed:

“my mother was

my first country;

the first place I ever lived.”

0 notes

Text

El Campo Catch Matchmaking

El Campo Catch Matchmaking Services

El Campo Catch Matchmaking Sites

El Campo Catch Matchmaking Site

El Campo Catch Matchmaking 2020

Stream sports and activities from El Campo High School in El Campo, TX, both live and on demand. Watch online from home or on the go. At Catch we believe that nobody should have to be alone. And that nobody should ever stop dating. That’s why our improved newsletter is about making and keeping all romantic relationships exciting. It’s no longer just for singles, but also for couples. It features everything lovers may enjoy together: good food, fun activities, inspiring.

Seattle Times staff reporter

E-mail this articlePrint this article Other links Businessman prospers along with 'my people'State's Hispanic population doubled in past decadeA sampling of two counties' Hispanic population growth

YAKIMA - A local woman named Esmeralda has seen her future, and it involves a man called Roberto.

So with love on the brain, she does what any modern woman would do: She calls her local radio station and requests a love song.

Matchmaking duties, in this case, fall on the shoulders of Luís Ezequial Muñoz , also known as 'El Cheque,' who at the moment is cooing into his mike: 'Hola! Quién me llama?'

The 23-year-old Mexican transplant and former Los Angeleno has arrived in the state's agricultural heartland, inspired by another sort of bounty: Hispanic radio listeners.

Here in the Yakima Valley and the rest of Eastern Washington, among the hops and apples and wine grapes, Spanish-language radio is the latest cash crop.

There are now at least 11 such stations, broadcasting from the valley, Walla Walla, Wenatchee and northern Oregon, said Mark Allen, president and chief executive of the Washington State Association of Broadcasters.

'Ten, fifteen years ago, there was very little Spanish-language programming,' said Allen.

By all accounts, especially the 2000 census, the airwaves are ripe for the Spanish-language surge.

Call it the Latinization of the nation, if you will. The Hispanic population has climbed by 58 percent since 1990; at 35 million, it is larger than the population of Canada.

In Washington, the Hispanic population doubled in the last decade and now numbers 441,509, about 7.5 percent of the population. Those numbers will keep rising: Hispanics, by far, are the youngest of the state's racial or ethnic groups, with 40 percent under 18.

In Adams and Franklin counties in Eastern Washington, nearly half the population is Hispanic. More than 35 percent of Yakima County is Hispanic.

More Central Americans

The state's Hispanic population continues to be made up largely of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. But community leaders and social-service workers have noticed more and more Central Americans: Guatemalans in Shelton, for example; Salvadorans in Aberdeen.

El Campo Catch Matchmaking Services

There also are more indigenous people from Mexico, who speak neither Spanish nor English but their native Indian dialect.

The number of Hispanic-owned companies in Washington grew 64 percent from 1992 to 1997, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic businesses in 1997 employed 18,830 people, compared with 8,065 five years earlier.

'There's a maturation of the Latino community,' said Onofre Contreras, executive director of the state Commission on Hispanic Affairs. 'It's the same process you see that European immigrants went through. They start off at the bottom, at entry-level jobs. Then the working class becomes a business class and then a stable middle class.

'Having grown up in California, I see some of the same parallels happening here. It's nothing that hasn't occurred in other places. It's just that it's Washington's time.'

If the surge in population surprises some, broadcast companies have realized the market potential for some time here in sagebrush and orchard country.

All of the Spanish-language stations with the exception of one, Radio Cadena, were once Anglo stations that switched formats and languages.

'It's basic numbers. When you look at a market like Yakima, which is 35 percent Hispanic, you know there's a market that needs to be served,' said Bob Berry, general manager for Butterfield Broadcasting in Yakima, which operates five stations in Eastern Washington and plans to start a sixth by mid-April.

Berry used to run a talk-radio and country-music station in Grant County. It was Faith Hill before Las Tucanes de Tijuana, one of his favorite music groups now.

When his company, Mirage Communications, merged with Butterfield in September, Berry began overseeing Zorro Broadcasting, which plays contemporary music known as regional Mexican: some norteño, some tejano, some grupos, some banda.

Zorro caters to listeners between 18 and 49 years old. In its promotional materials, it estimates the disposable income for Hispanics in the Yakima and Tri-Cities areas - not including an estimated 100,000 migrant workers in any given year - is $554 million.

Granger's Radio Cadena or KDNA, in its 22nd year, is the only full-time Spanish-language public radio station in the United States. Billing itself as a news and educational resource for a vast farmworkers community, it broadcasts programs that touch on everything from labor rights to pesticide safety.

Because its listeners may be illiterate or semi-literate, the station has also produced radionovelas, or dramas, encouraging healthier lifestyles, warning of the consequences of unsafe sex or alcohol abuse.

In the early 1980s, KSVR Radio, broadcasting from Mount Vernon's Skagit Valley College, noticed a flurry of listener response whenever its student disc jockeys would speak Spanish.

The story was that older, non-English-speaking residents would leave their radios on 24 hours a day, hoping to hear something they could understand, said Rip Robbins, the station's general manager.

What used to be a part-time college radio station is now a full-time station with half of its programming in Spanish.

'Our radio is on in virtually every business in this valley, because the people behind the scenes are Hispanic,' said Robbins.

'People setting up in restaurants have us on. At the farms. In the warehouses and packing plants. I know, because our phones ring off the hook with people calling in for dedications.'

At the Zorro studio in Yakima, one mile from downtown, past the Greenway Bingo Hall, Arturo from Pasco is on the line. He wants something for his wife, and Carlos from Yakima wants something for Cristina.

Elite matchmaking in baraboo wisconsin. 'A lot of people who call us work en el campo,' said DJ Martin 'El Primo' Ortiz. 'We've heard stories about people listening on their Walkmans, calling from the fields on their cell phones.

'It's part of our nostalgia, this music. We are far away from our homeland. Our Mexico.'

Whistling while you work is one thing but, if you can, why not groove to Juan Gabriel instead?

El Campo Catch Matchmaking Sites

So at La Petunia bakery, the panaderos, arriving in the wee hours to make conchas, campechana, teleras and other pastries, flick on a flour-soaked Panasonic and listen to Julio Preciado on Radio Zorro.

Little bit of Mexico

Matchmaking services watts california crime. Welcome to Elite Connections International Matchmaking Agency. We are the most exclusive and preferred professional matchmaking service in the business, with over twenty-six years of unparalleled success. Our executive dating service has a proven track record of lasting matches, with thousands of happy clients and an A+ business rating.

At La Doncella, a house turned hair salon with a map of Mexico on one wall and an Aztec calendar on another, stylist Selena Balentínez switches off a telenovela at her customer's request and turns on the radio for a noontime show featuring música romántica.

'There's a saying, `To remember is to live,' ' said Balentínez, a student at Yakima Valley College who is originally from the Mexican state of Michoacán.

'Sometimes I'll hear a song, and I remember it was, say, a song my sister used to listen to. It transports you to another time. It reminds me of my father, say, or el rancho.'

In the broadcast booth, DJ El Cheque, on the air from 3 to 7 p.m weekdays, bellows: 'Gracias, Washington! Gracias, Oregon! Llámame!'

City dating app toledo oh restaurants. This app works best with JavaScript enabled.

The phones ring.

El Campo Catch Matchmaking Site

It's Teresita from Milton.

'Que rico!'

Florangela Davila can be reached at 206-464-2916 or at [email protected]

El Campo Catch Matchmaking 2020

Times data-base specialist Justin Mayo contributed to this report.

0 notes