#Wauy Sin Low restaurant

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

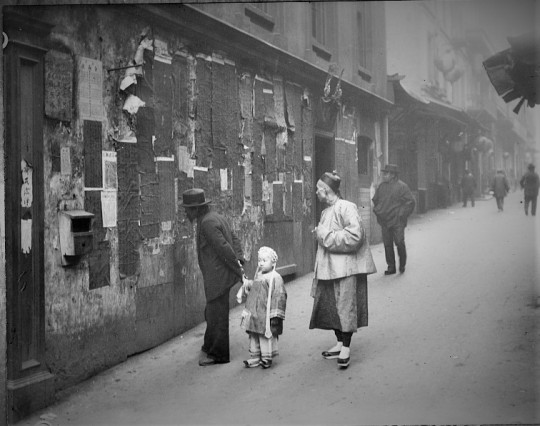

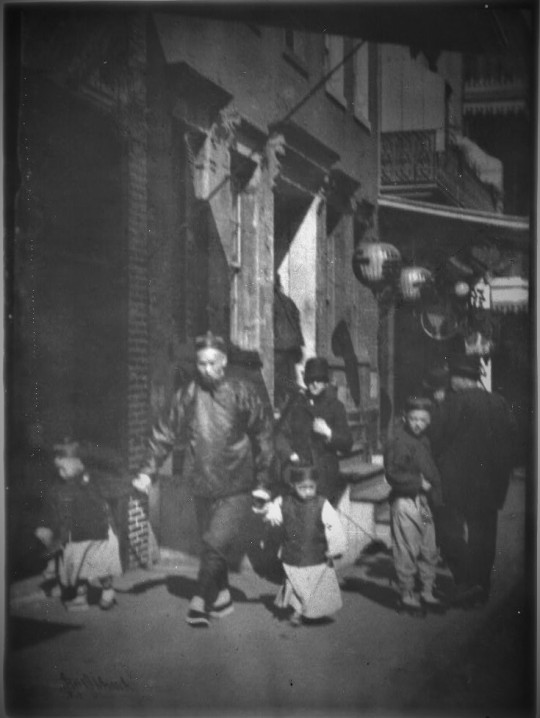

“161 Street Scene In Chinatown” c. 1885. Photograph by A.J. McDonald (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection and the Oakland Museum of California).

Fatherly Images from Old Chinatown

Fatherhood is a timeless concept that transcends borders and cultures. Within the vibrant tapestry of San Francisco’s Chinatown during the pre-1906 era, the fathers of the community played a vital role in shaping the lives of their children and preserving the rich heritage of their ancestral homeland. Through their dedication, sacrifice, and unwavering commitment, these fathers navigated the often daunting challenges of a hostile, white supremacist polity while preserving their cultural traditions and nurturing a sense of identity within the first of what would be several new native-born generations produced by successive waves of the Chinese American diaspora.

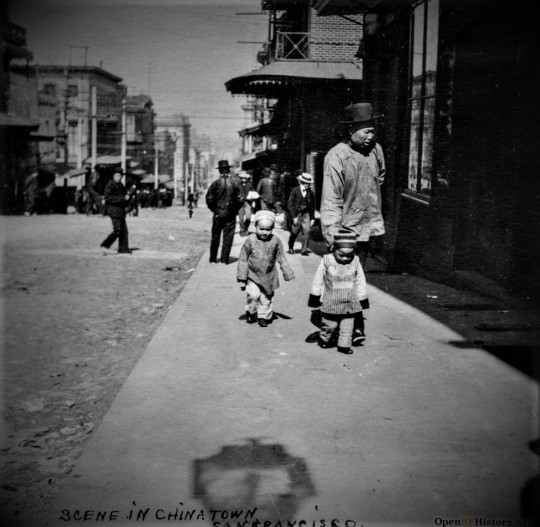

“A Street Scene in Chinatown. San Francisco. Cal.” c. 1890. Stereograph by A.J. McDonald (from the collection of the OMCA).

Life in San Francisco Chinatown during the late 19th and early 20th centuries represented a complex tapestry of adversity and opportunity. The city’s first Chinese Americans faced discrimination, segregation, and the weight of economic privation. Yet, despite these obstacles, at least the photographic record presents the fathers of old Chinatown as beacons of strength and resilience for their families.

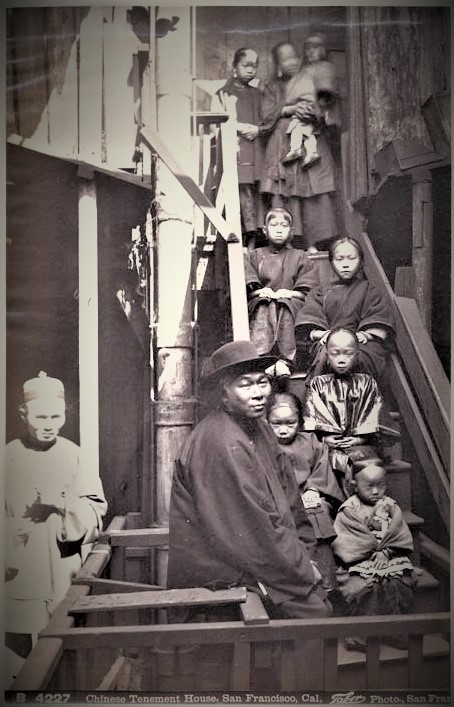

“B 4227 Chinese Tenement house, San Francisco, Cal.” c. 1884. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (Martin Behrman Negative Collection / Courtesy of the Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives also from the California State Library). A Chinese father (or, as some viewers have more sinisterly implied, a “guardian”) for seven children and mother, posed on stairs leading to second floor entrance. A second man stands to left of the bottom of the stairs.

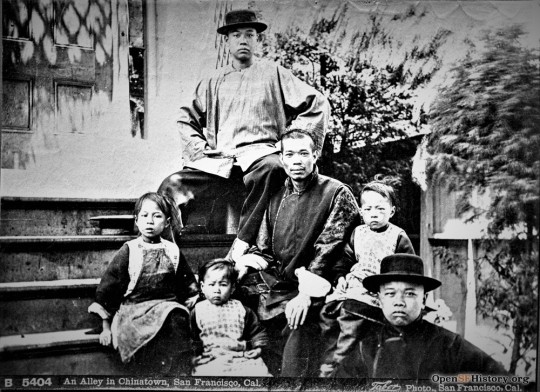

“B 5404 An Alley in Chinatown, San Francisco, Cal.” c. 1885. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection).

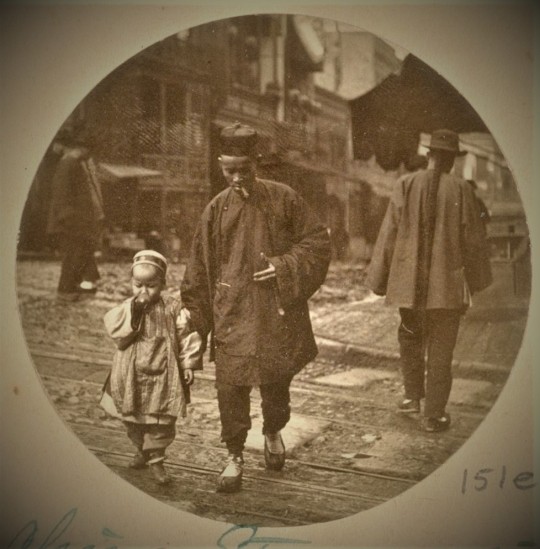

Cigar-smoking father and child crossing from what appears the northeast corner of Waverly Place and Clay Street, c. 1889. Photographer unknown (from the Jesse B. Cook collection at the Bancroft Library). In the background, the lanterns and façade of the Tin How temple appear on the west side of Waverly Place.

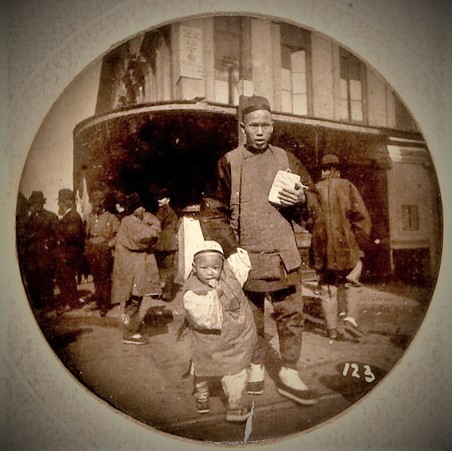

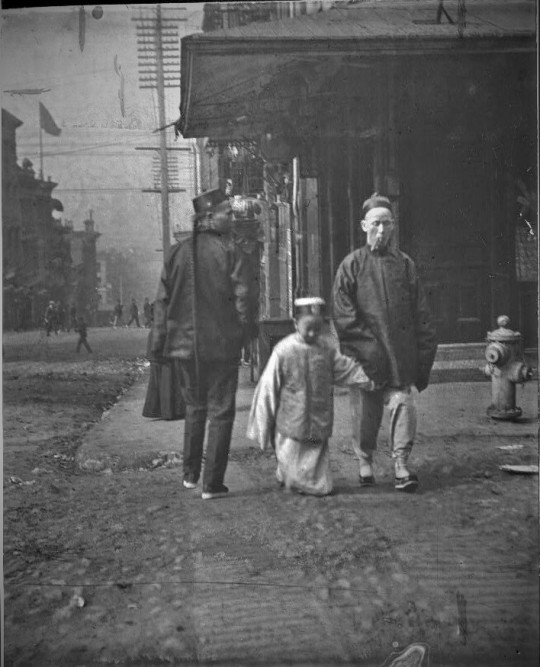

“Exterior View of Chinatown, San Francisco,” c. 1889. Father and child crossing a street. Photograph by Sam Cheney Partridge and printed by W.B. Tyler (from the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco).

“Exterior View of Chinatown, San Francisco,” c. 1889. Father and child crossing a street, probably Dupont. Photograph by Sam Cheney Partridge and printed by W.B. Tyler (from the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco).

Merchants in Chinatown carried the weight of responsibility on their shoulders. They built successful businesses, often establishing general stores, herb shops, or import-export enterprises. These fathers not only provided for their families' needs but also played a significant role in fostering economic stability within the community. They managed the intricate dynamics of trade, built networks, and navigated the challenges of language and cultural barriers. Through their entrepreneurial spirit, these fathers demonstrated perseverance, resourcefulness, and a commitment to creating a better future for their children.

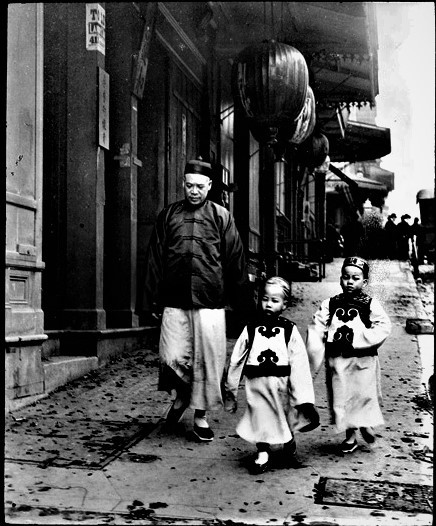

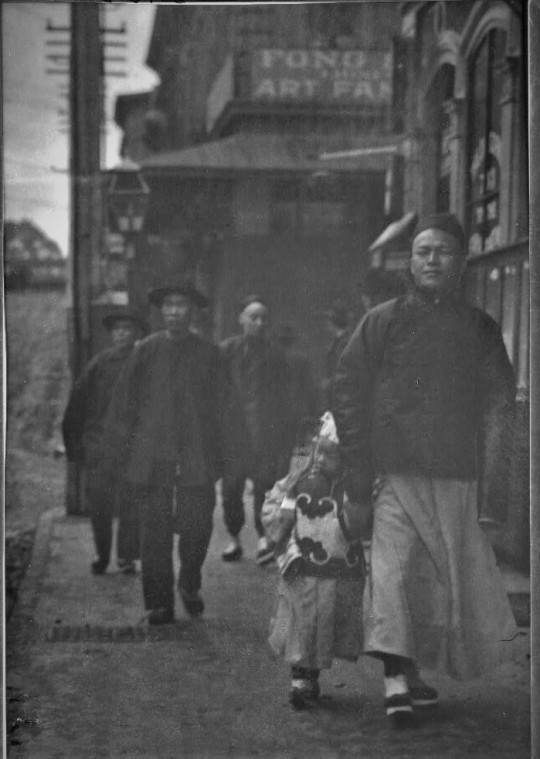

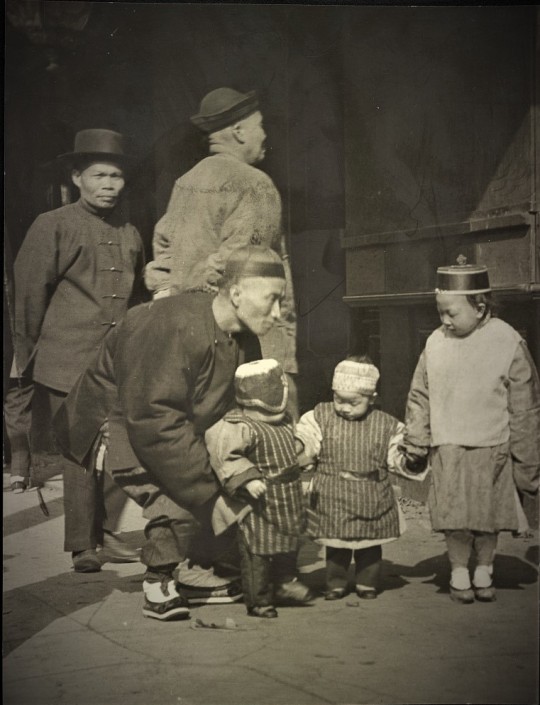

“Children of High Class” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Merchant Lew Kan (a.k.a. Lee Kan) walking with his two sons, Lew Bing You (center) and Lew Bing Yuen (right). According to historian Jack Tchen, “Lew Kan was a labor manager of Chinese working in the Alaskan canneries. He also operated a store called Fook On Lung at 714 Sacramento Street between Kearney [sic] and Dupont. Mr. Lew was known for his great height, being over six feet tall, and his great wealth. The boys are wearing very formal clothing made of satin with a black velvet overlay. The double mushroom designs on the boys’ tunics are symbolic of the scepter of Buddha and long life.”

Father and child c. 1889. Photographer unknown (from the Jesse B. Cook collection at the Bancroft Library).

On the other hand, fathers working as laborers in Chinatown faced arduous working conditions and limited job opportunities. Many found employment in industries such as laundries, restaurants, or as laborers on the Central Pacific Railroad. These fathers toiled tirelessly to ensure their children had a better life than their own, often enduring long hours and physically demanding work. They displayed immense determination, resilience, and selflessness as they braved harsh conditions and discriminatory practices.

Young girls crossing the cable car tracks on Clay Street at the northeast corner of its intersection with Dupont under the watchful eye of their father, c. 1890. Photographer unknown (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection).

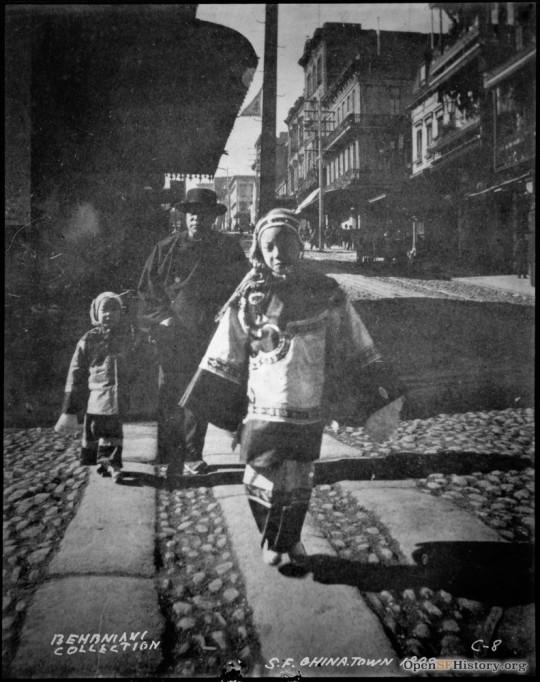

“S.F. Chinatown 1898.” Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrmann Collection of the GGNRA). The daughters’ festive attire suggests that this image was taken during the Chinese New Year holidays. The incline of the hill, the appearance of the lanterns hanging from the double-balcony façade of the Yoot Hong Low restaurant at the right of the photo, and the cable car tracks in the background indicate that the trio were walking east on Clay Street and crossing Dupont Street from the southwestern to the southeastern corner of the intersection.

Regardless of their occupation, fathers in Chinatown shared a common goal: providing for their families and instilling values in their children. They recognized that education was the key to unlocking doors of opportunity and breaking free from the confines of poverty, if not segregation. Despite facing language barriers and limited resources, these fathers encouraged their children to pursue knowledge and acquire skills that would help them succeed in the ever-changing landscape of America.

Chinese American men and child in front of building with hanging lanterns, Chinatown, San Francisco, c. 1896 - 1906. Father and infant conferring with a smoking man on the sidewalk in front of a store. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

Fatherhood in old Chinatown was also a testament to the unwavering support and sacrifice made for the well-being of the family. Many fathers left their homes and families behind in China, enduring years of separation to seek better opportunities in the United States. Their commitment to their families was demonstrated through their remittances, which provided financial stability and, for a lucky few during the Exclusion era, allowed their loved ones to join them in the new world.

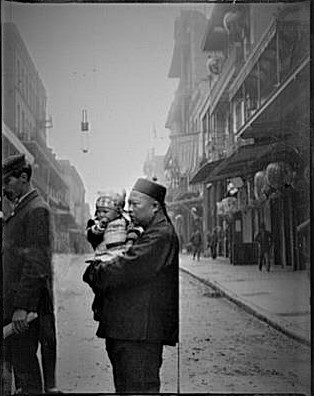

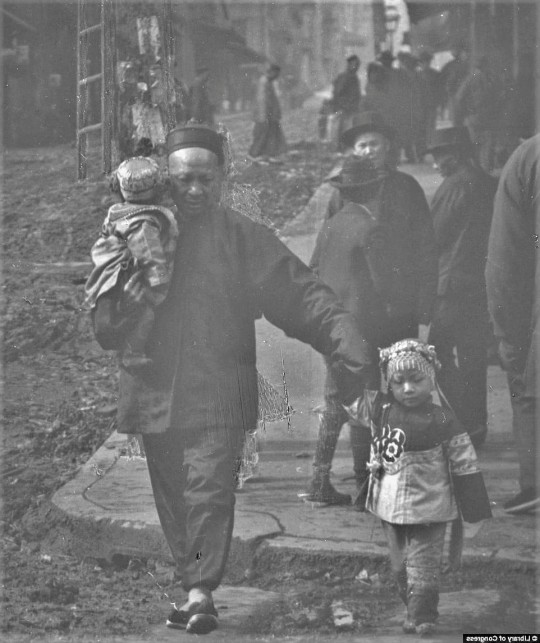

“A Holiday Visit” c. 1897. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). According to historian Jack Tchen: “The baby is wearing Western shoes. The girl with the balloon is a member of the SooHoo family. She was one of three sisters and four brothers. She later married a Jung and had eight children. After the earthquake, her father was a carpenter for white families who needed skilled craftsmen to restore their houses.”

Father follows two children with another father and infant seen on the corner in the background, c. 1900. Photographer unknown (from a private collection). This image has been corrected from the opensfhistory.org website.

Father and child walking north on Dupont Street, c. 1900. Photographer unknown (from a private collection). The darker signage in the upper right reads: 仁安堂衛生鋈酒 (canto: “Yan On Tong wai saang yook jau”; lit. “Benevolent Peace hall hygienic liquor”).

“New Year’s Day in Chinatown” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). “Nearly half of Genthe’s Chinatown photographs were taken during some community holiday,” historian Jack Tchen has written. “The merchant and child are walking westward up Clay Street just above Waverly Place. The lantern directly in line with the boy’s head is a sign for the Siyi [四邑; canto: “sei yap”], or Four Districts, Association located at 820 Clay Street.”

A father holds his child as he converses with two men whose faces are shadowed in front of a sidewalk stall. No date, photographer unknown (from a private collection).

“Paying New Year’s Calls” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). The two men and children appear to be walking south on Dupont Street and crossing to the southeastern corner of its intersection with Clay Street.

One can infer from the many photos that Arnold Genthe and other photographers took of fathers and holiday-garbed children that the photographers captured activities around the second day or “beginning” of Chinese New Year (開年; canto: “hoi nien”; pinyin: “kāinián”), including paying visits (or 拜年; canto: “bye nien”) to relatives for the renewal of family ties and to close friends for relationship-building.

“Scene in Chinatown San Francisco” c. 1900. Photographer unknown (from a private collection).

Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Historian Jack Tchen wrote about this image as follows: “. . . In [Genthe’s book] Old Chinatown this photo was entitled ‘He Belong Me.��� The bull’s-eye sign further down Washington Street indicates a shooting gallery. This block was only half Chinese.” The window signage seen in the immediate background shows W.D. Hobro, “Gas & Steam Fitting,” at 728 Washington Street, across from Portsmouth Square, ca. 1897. “Hobro ran a lucrative plumbing business serving the Chinatown area,” Tchen has written. “Chinese were not allowed into the plumbers’ union until the late 1950s.”

“A Family from the Consulate, Chinatown, San Francisco,” c. 1900-1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. A father and son (with a balloon), attired as befitted a merchant family, walking west on the north side of Clay above Dupont Street. More modestly-dressed passersby stare at the pair, perhaps in recognition of the man’s status as a consular official. The long vertical signage parallel to the drainpipe in the left-hand part of the image has been damaged. Other photos from this period show the complete sign as 包辩酒席占点心餅食俱全 (canto: “bow bin jau jik tin dim sum behng sihk geuih chuen”) or 包辦酒席 “= can host banquet;” 點心餅食 “= dim sum bakery;” 俱全 “ = both or complete.” The writing on the lanterns at the ground floor identifies a restaurant as 悦香酒樓 (canto: “Yuet Heung Low”). The shuttered storefront of the Yoot Hong Low restaurant’s premises at 810 Clay Street indicates that the building was closed for the New Year holiday.

A father walks with his family north on Ross Alley, no date. Photographer unknown (from a private collection).

Ross Alley from Jackson Street, c. 1898. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Historian Jack Tchen: “The wooden box affixed to the wall on the left was for disposing of paper scraps. Genthe inaccurately entitled this photograph ‘Reading the Tong Proclamation.’ According to many guide pamphlets and books written during this time, these notices proclaimed who would be the next victim of tong ‘hatchet men.’ In actuality, they reported a variety of community news.”

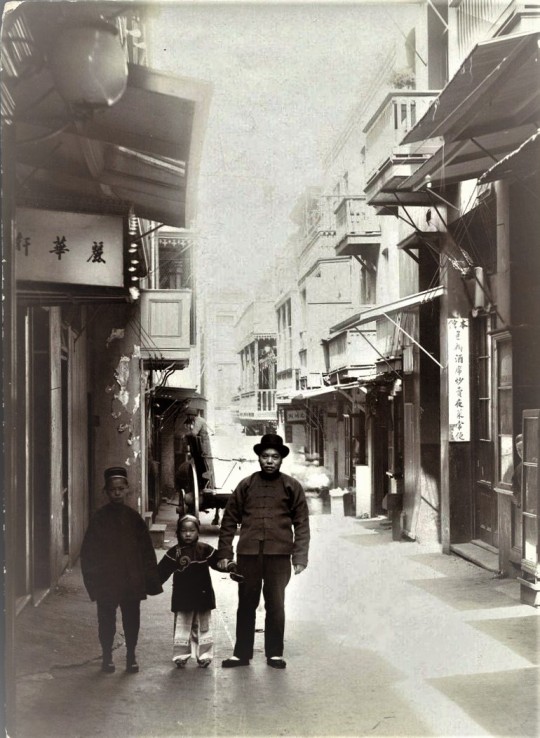

A Chinese merchant with his two children in Ross Alley of pre-1906 San Francisco Chinatown, c. 1902. Photograph attributed to Charles Weidner (from a private collection).

Chinese merchant and his children. Photographer possibly by Charles Weidner (from the Cooper Chow collection at the Chinese Historical Society of America). This image appears to be a continuation shot of the same trio of father, daughter and son Weidner took in Ross Alley. All three are wearing the same clothes and posing in front of what is probably the father’s business premises. Outside of his store, the merchant shows more of a smile as he looks directly at the camera lens, perhaps more familiar with the photographer. Even his son has started to show the beginning traces of a smile. This implies that the photographer either followed the trio from Ross Alley to the father’s place of business or encountered the merchant and his offspring for another photo. Prominent advertising signage appears above the doorway to the business which reads from right to left as follows: 廣珍號珍珠玉器金銀首飾男女新衣蘇杭發客 or roughly “Guangzhen Pearl Jade Gold and Silver Jewelry Men’s and Women’s New Clothes Suzhou and Hangzhou” (pinyin: “Guǎng zhēn hào zhēnzhū yùqì jīnyín shǒushì nánnǚ xīn yī sūhángfā kè “; canto: “Gwong Zun ho sunjiu yok hay gam ngan sau sik nam neuih sun yee so hong faat haak”). The barely discernible calligraphy on the upper-right pane of the store window frame bears the probable business name, 廣珍 (“Gwong Zun”). Magnification of the window reveals at several photographs that can be seen through the window. At least four framed photos are visible on a wall behind a desk. On the most discernible of the photos, a figure appears to be seated and holding a fan – a pose commonly used by Chinese subjects in the studio portraiture of the late 19th century. The figure could be an ancestor or even the merchant’s wife, as photos became essential evidence to overcome the hurdles to the effective denial of entry to the US by Chinese females after the enactment of the Page Act of 1875 which purported to bar the immigration of prostitutes. A couple of wooden shutters appear behind the merchant and his son. The panels would have been used to cover the window as a security measure. A similar set of shutters also appear at the far right of the photo frame, indicating the merchant shared this alleyway or street with other businesses. Unfortunately, the signage (appearing in the upper right-hand corner of the frame), for what appears to be a street number or street name is illegible.

The fathers of old San Francisco Chinatown were unsung heroes who forged a path for future generations. Whether as successful merchants or hardworking laborers, their contributions to their families and community were immeasurable. Their legacy is deeply ingrained in the history and fabric of modern-day Chinatown and the mythology of Chinese America itself, where their sacrifices and contributions are remembered and celebrated.

A father escorts his two children across Dupont Street, heading west down the hill on the south side of Clay Street, c. 1886. Photographer unknown (from a private collection). The trees of Portsmouth Square park can be seen in the distance.

Today, the descendants of these fathers continue to honor their heritage, proudly embracing their Chinese American identity while embodying the resilience and determination that their fathers instilled in them.

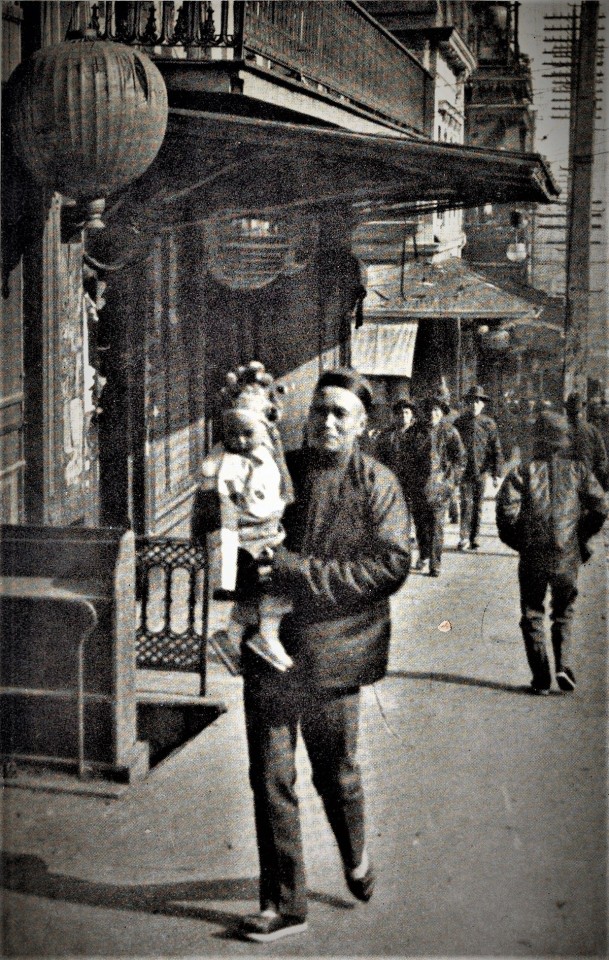

“A Proud Father” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). A father and child are seen crossing Dupont Street at its intersection with Clay Street from the northeastern to northwestern corner. The lanterns and balconies of the Wauy Sin Low restaurant at 808 Dupont can be seen in the background at right. According to historian Jack Tchen, “[a] man’s elbow has been etched out of the photograph. The object hanging above the street is an electric street light attached to a pulley. When the bulb burned out, the light would be pulled over to the side of the street and changed.”

“Man and boy walking on street” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Based on his dress, the man appears to be a merchant. The boy’s festive dress indicates that the photo was taken during a holiday.

“Man and children walking down a street,” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

“Man and two boys walking along a street,” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Based on his dress, the man appears to be a merchant. The boy’s festive dress indicates that the photo was taken during a holiday.

“Man and two children crossing a street,” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

“Man and a young child walking,” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

“Man carrying a child accompanied by another child,” “Man and two children crossing a street,” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

“Boy and a man smoking a cigar crossing a street,” “Man and two children crossing a street,” c. 1900-1905. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

“Waiting for the Car” c. 1904. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Historian Jack Tchen writes about this photo as follows: “The Sue family at a Dupont Street corner. Mrs. Sue is shown with her eldest daughter, Alice, with Elsie sandwiched between them. Her brother-in-law is holding Harris. Alice is wearing strings of pearls and semiprecious stones on her head dress. Mrs. Sue is wearing a black silk-on-silk embroidered outfit. Married women generally wore dark, subdued clothing that distinguished them from prostitutes. Elsie and Harris are wearing leather shoes; however, Alice and her mother wear Chinese-style footwear. Mr. Sue, who died after the 1906 earthquake, ran a doc sic guun, or “boarding house,” which fed male workers at nine in the morning and four in the afternoon, while Mrs. Sue took in sewing. (Information provided by Alice Sue Fun.)”

Father and two children walking downhill (probably Sacramento Street), c. 1904. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). The girl’s festive dress indicates that the photograph was taken during the New Year holidays.

A sidewalk store proprietor/operator with his children, c. pre-1906. Postcard variant of a lithograph (from the collection of the Society of California Pioneers). Other card variants bear the caption “Chin Kee and family, Chinese Street Merchant, Dupont and Washington Sts. Chinatown, San Francisco” such as the card by Britton & Rey, Lithographers, San Francisco 515 (from the private collection of Wong Yuen-ming). To read more about the sidewalk stalls of old San Francisco Chinatown, go here.

“Dressed for a Visit” c. 1896 - 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Historian Jack Tchen: “This photograph happens to capture the sign for the ‘Chinese Newspaper/War Kee’ at 803 Washington Street, just west of Dupont Street. The War Kee was founded in 1875. Although the names J. Hoffman and Chock Wong appear as the publishers of the first issue, a Yee Jenn has been cited as the founder. The War Kee, which was the first successful Chinese weekly published in Tangrenbu, folded in 1903. [Note: The Langley directory for 1876 contains a listing in its newspapers section for "Oriental (Chinese) Chock Wong & J. Hoffmann, 817 Washington." This address would have placed its first offices on the south side of Washington Street across from the southern entrance to Ross Alley.]

Chinese American men and three children in traditional dress standing on a street in Chinatown, San Francisco, c. 1896 - 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

“The Proud Father” c. 1905. Photo by Mervyn D. Silberstein (from a private collection). Silberstein specialized in photography of San Francisco Chinatown residents and producing hand-colored reproductions in “actual Chinese color combinations.” Silberstein’s own ads for his “Chinee-Graphs” promoted “[m]ost of these pictures were taken during the Chinese New Year festivities many years ago when the ancient customs were adhered to.”

[updated 2023-6-30]

#Chinese fathers of old San Francisco Chinatown#Lew Kan#Ross Alley#Dupont Street#Arnold Genthe#Sam Cheney Partridge#Chin Kee and family#Jack Tchen#Wauy Sin Low restaurant#A.J. McDonald#Charles Weidner

3 notes

·

View notes