#Wasim Ahmad Alimi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

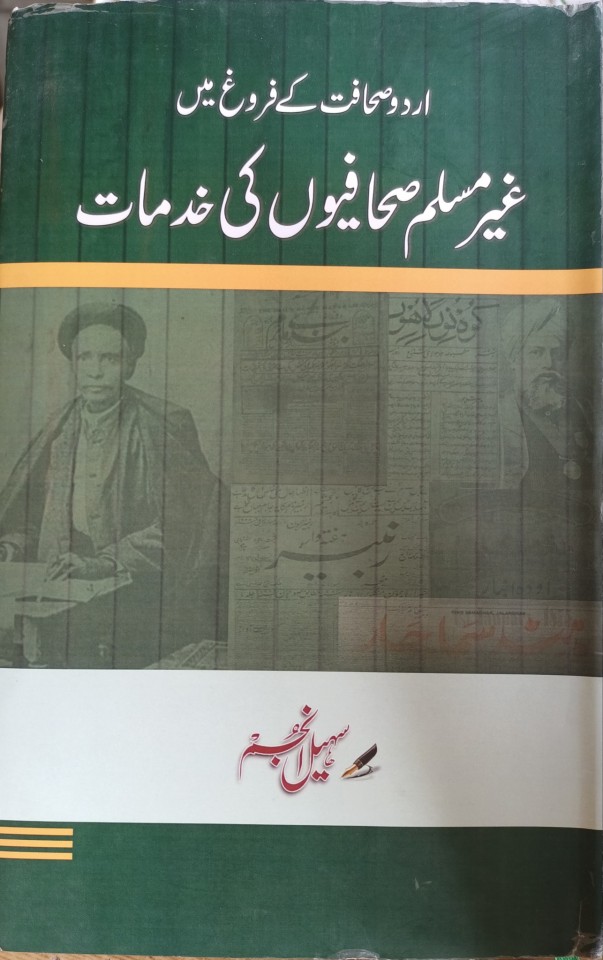

Unsung Contributions Through Inclusivity and Secularism During 200 Years of Urdu Media

Book: Ghair Muslim Sahafiyon Ki Khidmaat

Author: Suhail Anjum

Review: Wasim Ahmad Alimi

Publisher: Nomani Printing Press, Lucknow

Pages: Approximately 368

Sohail Anjum’s latest literary contribution, Urdu Sahafat Ke Frogh Mein Ghair Muslim Sahafiyon Ki Khidmaat, is a monumental exploration of an overlooked yet profoundly significant subject: the contributions of non-Muslim journalists in the evolution and growth of Urdu journalism. Published with the support of the Fakhruddin Ali Ahmad Memorial Committee, this book is a valuable addition to the rich historiography of Urdu journalism and is an ode to its inclusive and secular ethos. The book carries a foreword by Dr. As'ad Farooqui, whose scholarly perspective sets the tone for the narrative. With the intention of promoting the culture of buying Urdu books, I managed to own a copy of the same by ordering it online, making payment and receiving it by post to my office address. Sohail Anjum is no new to me, I have often read his columns in Daily Urdu Inquilab editions of Delhi and Patna, and his review writing was a part of my translation of Dr Anwarul Haq’s Novel in Urdu. Sohail Anjum was born and brought up in historical district, Sant Kabir Nagar of Up having the degree of master’s from the prestigious AMU. He is currently associated with Voice of America, Urdu Services.

Dr Asad Faruqui ‘s specialization is in medical journalism in India and hence he adds a valuable point in this account by “This is obvious that all the communities of India have contributed to the promotion of Urdu. According to my personal study between 1855 and 1900, nearly 24 Medical Journals were published, out of which a significant number were edited by Non-Muslim Journalists who played a pivotal role in shaping the medical discourse of the time.” (Preface, pg No.21)

The book opens with a historical overview of Urdu journalism, tracing its origins back to Jam-e-Jahan Numa, the first Urdu newspaper published in 1822. Anjum elaborates on the unique cultural and political context that nurtured the growth of Urdu journalism, from its beginnings as a vehicle for disseminating information to its later role as an instrument of socio-political change. Sohail Anjum at the end of this chapter, discusses the religious journalism as well in which he says that the narrative of religious journalism was first introduced by Britishers to promote missionaries in India, and papers like Barhmanichal Magazine was only the reaction of it.

Sohail Anjum expertly weaves the narrative of Urdu journalism’s role in India’s freedom struggle and its post-independence challenges. He sheds light on the ethical and intellectual standards that shaped this profession, emphasizing the diversity and inclusivity of voices that contributed to its legacy. Anjum’s narrative underscores how Urdu journalism became a symbol of unity and a platform for dialogue in a multicultural society.

The heart of the book lies in its exploration of the contributions made by non-Muslim journalists, who embraced Urdu as their medium of expression and activism. Anjum offers a nuanced portrayal of these individuals, presenting them not merely as journalists but as visionaries and patriots. There are more than 60 figures of Urdu Journalisms who have been identified by Anjum to help him establish his point of Non-Muslim Urdu Media persons from Hari Hardatt, Munshi Nawal Kishore, Master Ramchandra, Lala Deenanath, Lala Lajpat Roy, Munshi Daya Narayan Nigam, Sardar Deewan Singh Maftoon, Jamna Das Akhtar, Fikr Tonsi to Balraj Menra and PP Maseeh. To understand the style and the way of biographical historiography in this book I am translating the shortest sketch from the and the smart readers like you will get the sense of other heroes without going into deep:

“Pandit Mukund Ram

Pandit Mukund Ram was born in Kashmir in 1828 and passed away in 1897. Among the newspapers that gained significant prominence in Lahore during the 19th century, two stood out: Paisa Akhbar and Akhbar-e-Aam. The latter was founded by Pandit Mukund Ram himself. Before venturing into journalism, he worked as a scribe at the Koh-i-Noor, a weekly newspaper edited by Munshi Harsukh Rai, in 1847. However, Mukund Ram harbored a deep desire to establish his own printing press. This ambition led him to set up a press under the name Mitra Vilas, through which he began publishing Hindi books. His two sons, Gopi Nath and Govind Sahay, assisted him in this endeavor.

Amidst these ventures, Mukund Ram developed an interest in publishing newspapers. In 1870, he launched Huma-e-Punjab. However, a year later, in 1871, he started Akhbar-e-Aam, which went on to achieve significant popularity. This newspaper played a crucial role in elevating the standards of Urdu journalism. Pandit Mukund Ram also published a Hindi newspaper titled Mitra Vilas, which gained considerable acclaim and was published for nearly two decades. Additionally, he founded an English newspaper, People's Journal, although it was Akhbar-e-Aam that brought him enduring fame.In 1861, he also launched a monthly magazine titled Baghawat-e-Hind from Agra.” (pg No.311)

The profiles of pioneering figures such as Hari Hardat and Munshi Sadasukh Lal, to whom the book is dedicated, are particularly striking. Anjum recounts how these individuals navigated a complex socio-political landscape, using Urdu to champion the causes of equality, justice, and reform. The book highlights their unwavering commitment to the language and its ethos, which often came at a personal cost. Indeed, Urdu Journalism has a rich history in India not only in terms of language but also in uniting the people in the name of national interest and calling them together to fight against the tyrant Britishers. I personally tried to sketch the forgotten story of Molvi Baqar, the first Indian martyred journalist in my short story titled as ‘Akhond’(The highly literate) in which I have portrayed Baqar’s journalistic contributions through Delhi Urdu Akhbar and his martyrdom by the Britishers. Interestingly, the story has been narrated by his Bonafide son Shamshul Olema, Maulana Mohammad Hussain Azad.

The section titled “The Galaxy of Non-Muslim Journalists” is a treasure trove of information. It profiles stalwarts like Shanti Narayan Bhatnagar, whose work in Swarajya exemplifies courage and resilience. By documenting their lives and contributions, Anjum brings to light the secular spirit that has been a cornerstone of Urdu journalism.

One of the strengths of Anjum’s writing is its ability to balance scholarly rigor with accessibility. While the book is deeply rooted in research, it is written in a style that appeals to a wide audience, from academics to general readers. The narrative is enriched with archival material, historical anecdotes, and critical insights, making it a comprehensive resource for students and researchers of Urdu literature and journalism.

Anjum also explores the stylistic evolution of Urdu journalism, analyzing its literary richness and its role in shaping public opinion. He discusses how non-Muslim journalists contributed to this stylistic evolution, bringing their unique perspectives and sensibilities to the craft.

In today’s world, where divisions often overshadow shared histories, Anjum’s book serves as a powerful reminder of the inclusive and unifying spirit of Urdu journalism. It challenges the reader to reflect on the secular and collective efforts that have defined the language’s legacy.

The book’s relevance extends beyond the realm of journalism. It is a testament to the cultural synthesis that has shaped India’s history and underscores the role of Urdu as a language that transcends religious and cultural boundaries.

Urdu Sahafat Ke Frogh Mein Ghair Muslim Sahafiyon Ki Khidmaat is more than just a historical account; it is a celebration of a shared cultural and intellectual legacy. Sohail Anjum has crafted a narrative that is both enlightening and inspiring, shedding light on the often-overlooked contributions of non-Muslim journalists to Urdu journalism.

This book is a must-read for anyone interested in the history of Urdu, the dynamics of Indian journalism, or the broader themes of cultural dialogue and inclusivity. Anjum’s work is a timely reminder of the values that have sustained Urdu journalism for over two centuries, offering valuable lessons for the present and future.

***

Wasim Ahmad Alimi

In charge Officer, Block Urdu Language Cell,

(Cabinet Secretariat Department, Govt of Bihar)Jalalgarh, Purnia, Bihar, 854327

[Former Translator-CCRUM, Ministry of Ayush]

0 notes

Text

نظم: مجھے سب یاد ہے اب تک

کسی نخلِ تمنا کا

میں برگِ جستجو بن کر

ہواؤں کے تھپیڑوں میں

ہمیشہ شاد رہنے کی

خودی آباد رکھنے کی

طلب میں شاد رہتا تھا

خودی آباد رکھتا تھا

کبھی میں برگ تازہ تھا

کلی کونپل شگوفہ تھا

کبھی میں زندگی بن کر

شجر پر مسکراتا تھا

وہ میرا عہدِ طفلی تھا

عہد کیسا؟ وہی جس میں

زمانے کے حوادث کا

زہر آلود رنجش کا

نہ کوئی خوف ہوتا ہے

نہ کوئی رنج ہوتا ہے

نہ کچھ احساس ہوتا ہے

بلوغت کی کہانی بھی

انوکھی ہے، نرالی ہے

کہ جب میں سبز ڈالی پر

گلِ رنگیں کے پہلو میں

چمن کا رازداں بن کر

گلوں کا پاسباں بن کر

شجر پر رقص کرتا تھا

مجھے سب یاد ہے اب تک

چمن کا بوٹا بوٹا جب

غریق سیل مستی تھا

وہ جب ہر قطرۂ شبنم

گلوں کو غسل دیتا تھا

کبھی ایسا بھی ہوتا تھا

نسیمِ صبح کا جھونکا

عروسِ گل کے سینے سے

دوپٹہ کھینچ لیتا تھا

میں تب بھی حوصلہ بن کر

مکمل فیصلہ بن کر

شجر پر رقص کرتا تھا

مجھے سب یاد ہے اب تک

چمن کی ڈالی ڈالی جب

فروغ حسن سے مملو

تقدس ریزی کرتی تھی

اچانک کیا ہوا اک دن

چمن کے درمیاں ہو کر

زہر آگیں ہوا گزری

ہوا ایسی کہ جس نے بس

بہت تھوڑے سے وقفے میں

گلوں کی زندگی لے لی

کلی مرجھا گئی اک دم

مسرت نے گگن چھوڑا

عنادل نے چمن چھوڑا

مجھے سب یاد ہے اب تک

چمن کا پتہ پتہ جب

شہیدِ آرزو ہو کر

زمین دل پہ بکھرا تھا

بڑا پر درد لمحہ تھا

کہ جب میں اک دم تنہا تھا

بہت روتا بلکتا تھا

مگر وہ سسکیاں میری

پریشاں ہچکیاں میری

کوئی سنتا بھلا کیوں کر

کہ اس گلزار کا نقشہ

بھی اب انسانوں جیسا تھا

جہاں معصوم جانوں کا

جہاں بھوکے پیاسوں کا

جہاں پر خون میں لتھڑی

ہوئی بھائی کی لاشوں کا

جہاں زانی کے چنگل میں

پھنسی معصوم بہنوں کا

نہ حامی ہے نہ پرساں ہے

یہ کیسی بزم انساں ہے

***ااا***

0 notes

Text

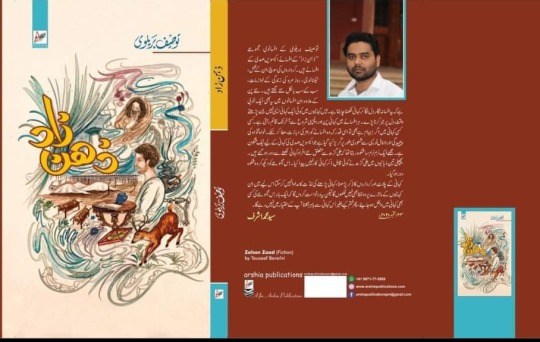

Zehan-Zaad: A Bold Attempt to Deviate from the Traditional Mode of Urdu Storytelling

Wasim Ahmad Alimi (PhD Scholar, Dept of Urdu, JMI, New Delhi)

‘Zehan-Zaad’ is a debut collection of Urdu short stories by a young essayist, translator, and storyteller, Tauseef Bareilvi. He comes from Bareilly district of UP. He’s got a PhD in Urdu literature recently from Aligarh Muslim University. The stories of Dr Tauseef Bareilvi are structurally interconnected. The technique of personification, psychological narrative, mix coding language (using English words and sentences directly written in English.), creating plots of sci fiction, keeping story ‘the shorter the better’ and taking themes and characters from different spheres of life are the major findings of ‘Zehan-Zaad’. The first and foremost verdict we may pass about his creative writing is that the writer has successfully attempted to adapt material and ideological culture of our time, rather than wandering in the past. The finest example for this claim is the sixth story from this collection, ‘Ashtray’. The story is based on the concept of re-virginity surgery, a cosmetic procedure used to reconstruct the torn hymen of a female.

As we all know that in our conservative society being sexually intimate with other hurts the ego of partner and religiously is a taboo as well. Tauseef Bareilvi has beautifully woven the threads of the concept for making of this story. For the confirmation one can read the tragic ending of the story, ‘Ashtray’:

“You have become hollowed from inside. You are not that Stella whom I met ten years ago. You are no more able to please anyone.”

These are the situations that compel female partners to go through hymenoplasty in our patriarchal society. As the female protagonist replies:

“Yes, I have been hunted by the situations.”

The adaptation of imaginative and scientific elements in his stories, predicts a good future of Urdu fiction. All the new themes that Tauseef Bareilvi has tried to utilize in his stories seem to be structurally connected with one another. The interconnectivity of the stories will be further discussed in detail later at the end of this paper.

The Title: The book, ‘Zehan-Zaad’ comprising of 136 pages of fiction is purely a product of a young writer’s imagination. The name itself gives meaning to the title, in Urdu, ‘Zehan’ means ‘mind’ (Imagination) and ‘Zaad’ is an adjective from the Persian verb, ‘Zaeedan’ which means to give birth to someone or something. Hence, ‘Zehan-Zaad’ can loosely be translated as ‘The product of an Imagination’. But in the depth of the word ‘Zaad’ are other meanings and surprisingly every one of them can be attributed to the title.

‘Zaad’ also means ‘the supplies and money of a long trip’ when it comes with Urdu word, ‘Raah’ (the journey) as ‘Zaad-e-Raah’ (supplies and money preserved for a journey) or ‘Zaade-e-Aakhirat’ meaning the supplies and preparations for the life hereafter. All this linguistic explanation is to define the title that it is not only the product of imagination but also the supplies and necessary preparations for the journey of creative writing. This collection has a story with the same title.

The Personification: The technique of personification has been used in the story, ‘Zehan-Zaad’ where a non-human character is described as living being. Two major creations of our imagination, ‘Tasneef and Taleef’ (Creative Writing and Composition) have been personified as the active characters and the ‘imagination’ that gives birth to them is in the center. The story begins with the fine concept of reproductive biology. The comparative elements between the creations of sperms in the womb and creation of story in the imagination racing to life have been highlighted in the beginning:

“Why are you crying my dear Qirtas? You need not to cry, you are not alone. If you think your existence is hypothetical, so is mine, want to make you assured. You are far better than those millions……Yes those are in millions in the race of life, but only one wins the race and all others lose their lives and get buried forever. You are not like them. You did not suppress your siblings in the battle of life.” (Zehan-Zaad, pg 75)

The story further unfolds itself with the dialogues between father and his children. Qirtas is a little bit upset who has grown up now to a handsome boy, repeatedly asking for traces of his mother. The next part of the story revolves around ‘Taleef’ (the composition), her innocent questions and some thoughtful answers from her father. The entire plot has been woven by simply personifying the roots of creating in such a living manner that you will feel like characters have not been personified, they are actual living beings.

Another story, ‘The Writer and the Writing’ in this collection has the same thematic approach, the same style of writing, similar usage of personification, equal pace of dialogues and resemblances of storiness. My earlier claim that Tauseef Bareilvi’s stories are structurally interconnected gets certified with the similarities between his two aforesaid stories. You just need to remove the title and merge two in one, you will get a single and, of course, a larger one. But this can’t be judged as a weak point of a writer, sometimes creative writings come as the extension of previous one.

The Sci Fiction: The headline of my essay suggests that the stories by Dr Tauseef are reconstructing the torn hymen of Urdu tradition of storytelling. Basically, what I want to conclude is that we, as Urdu readers, have become bored with repeated themes. Almost 70% of Urdu stories depict a particular culture. Names of the characters always being from Indian Muslim backgrounds, and the plots setting in the rural areas and characters doing ordinary things make no difference in Urdu stories. In terms of themes, usage of language, name of characters, and length of story, Tauseef Bareilvi has dared to deviate from this repetition and has created a new plotting world for his readers. He is giving a new direction to Urdu stories. His story, ‘Ta’zeeb’ (The Punishment) is a fine example of the same. It is a scientific story that deals about the fictitious scenario of a long future which seems to be around 2050s when air and water is severely polluted, agricultural land is deserted, inhaling oxygen only in balconies, forests are vanished, different species of worms and insects are extinct, glaciers already melted out and overtaken number of islands, global warming has grown to a higher and unbearable extent, sky is full of drones, flying carts and home delivery of daily life stuffs is being done through robots and drones, electric bulbs are regulated with censors, human breathing is dependent on oxygen cylinders and almost every aspect of life has gone online. And the love story of Wahid and Maria is beautifully running between the lines. They are college friends now a married couple, Maria is affirmative to settle somewhere in space or some other planet. Finally, the story ends on a tragic climax where communications between earth and the Maria’s planet are broken, and Wahid is upset thinking of those sperms and ovaries Maria had preserved in a ‘Scientific Lab’ for their family planning.

“What possibly would have happened to those sperms and ovaries? They did not choose a space life. What is their mistake that they would have been hanging in space due to gravity, they were to start a new life altogether, the life biologically linking me and Maria. At least this was the last thing to sustain an invisible relation between us.” (Ta’zeeb, pg 132)

What makes this story different, is the emotional touch between scientific pictorial descriptions of a long future. The moral of the story is that no matter how much developed the world becomes, machines can never destroy the human emotions and can’t cure the grief of a man.

Science-fiction (sci-fiction) is not something new. Comics and stories predicted about powered-cars, mass destructive weapons more than a century ago. Writers from their speculative imagination have frequently written about future. One such powerful story that I have gone through is of one and only Iranian Legend, Sadeq Hedayat. His mysteriously titled story, ‘SGLL’ (س گ ل ل) is no doubt a masterpiece in terms of sci fiction. He has written about two thousand years afterward world when human ethics, morals, emotions and lifestyle is completely changed, knowledge has become practical, family system is collapsed and people live in larger buildings like honeybees in their hives. The story of Sadeq Hedayat revolves around two intellectuals, Sosan and Tad. Unlike Sadeq Hedayat, in the story of Tauseef Bareilvi, time and space seem to be around near future but not the nearest one. In Hedayat’s story people are struggling for death and in the story of Tauseef, for life.

Although there is no comparison of one story with another, but the thematic way of storytelling unwillingly links a young writer with a legend.

A 2017 short film, ‘Carbon: The Story of Tomorrow’ written and directed by Maitrey Bajpai and Ramiz Ilham Khan, featuring Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Prachi Desai, also sets the same environment of future (2067) when oxygen and water are costlier than diamond and gold. The only thing which prevails is carbon. The film begins with the tale of our planet’s greenery which for now has become a story of grandmothers only:

“Endless blue skies, Children playing in the lush-green fields, Romance amidst the first rain, Sound of the ocean, Water everywhere, And oxygen to breathe, Many years ago, our Earth used to be like this.”

The film has 11 million views on YouTube. The story of Dr Tauseef Khan also sets in future but doesn’t make the surroundings horrific, whereas the film horrifies the scenario by the scenes of murders, smuggling of oxygen and water, trafficking of women by the migrated citizens of Mars. Reading the story makes you a little emotional while watching the film terrifies you about the future.

Writing too much about every story one by one will only spoil the interests of readers. The concluding lines about the collection, Zehan-Zaad can possibly be pronounced is “The Briefest Stories having the Taste of Mix-coding Language, memorable characters, exciting themes and a virgin style of creative writing in Urdu.”

(The book is the recipient of Sahitya Academy Yuva Prushkar for 2023. Have a fabulous experience of E-book with lowest price @ NotNul. Hard copy can be bought from Urdu Bazar. One can also get it directly from the Publisher @ 9971775969 Arshia Publications, Old Delhi)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Translations of Death and Dream in Ghazals of Safeer Siddiqui

By Wasim Ahmad Alimi

Khokhli Awaz de jati ha ab dastak Mujhe

Kha Gayi Yun Dheere Dheere Zeest Ki Deemak Mujhe

(The life, like a kind of canker has slowly eroded me in such a way that, even a meaningless call surprisingly knocks me.)

Young, energetic, enthusiastic, and emerging Safeer Siddiqui is a poet of death and dream. A student of just M.A. Urdu in Jamia Millia Islamia has gained so much mastery and maturity in poetry that his seniors like me think that Safeer is a time traveler who is travelling in past. The elements of death and metaphors of dreams are looming large in his ghazals that have been recently printed as ‘Khawabon ke Marsiye’ [Elegies of Dreams]. This anthology of 72 ghazals beautifies emotions of self-killing in an artistic way that some of his fellow poets has started to call him ‘the ambassador of death’. Interestingly his name, ‘Safeer” also means ‘the ambassador’.

Before we examine his nihilistic and poetic approach, let’s have a look at the significance of solitude, grief, darkness, dreams, and despair in already written literature of the world.

It is as clear as the sunshine that we will die any day. None can deny the fact that our timespan on this planet is not deathless. Then the question arises here, how we deal with the knowledge that we will die. American cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker in his book ‘The Denial of Death’ (1974) discusses this theory in detail. He says that we do not try to recognize our death because this is a terrible thought to live with, we cannot enjoy the life with this thought, hence we do not take it seriously. The book won the Pulitzer Prize of the year 1974. Author, Ernest Becker says in his book:

“It is fateful and ironic how the lie we need in order to live dooms us to a life that is never really ours.” [Becker, 1973: 56].

In the light of above-mentioned theories, this couplet of Safeer Siddiqui gets complete meaningfulness:

Marte Rahte Hein Har Ek Pal Ki Na Mar Jaein Kahin,

Jeene Walon Ka Ajab Ishq Hai Mar Jane Se

(We die every now and then with the fear of death, living people have a wonderful affair with mortality.)

This is exactly what our terrible death demands from us. Death is not a final episode, its indeed a continuous process that develops throughout the life. The legendry Iranian Fictionist and the founder of modern Iranian Short Stories, Sadeq Hedayat explains the same in his world-renowned novel, The Blind Owl:

“Many people start dying just from the age of twenty.”

“My one fear is that tomorrow I may die without having come to know myself.”

“If there was no death, everyone would wish for it.”

These three different excerpts from Sadeq Hedayat’s novel, validate Safeer’s affair with the elements of mortality when he says the followings:

Maut Ki Dhun Pe Tharaktey Hein Haqiqat Ke Qadam

Zindagi Jeetey Hein Bas Khawab Dikhaye Huwe Log

(The life dances with the rhythm of death, alive are only those living in dream.)

Khokhli Awaz de jati ha ab dastak Mujhe

Kha Gayi Yun Dheere Dheere Zeest Ki Deemak Mujhe

(The life, like a kind of canker has slowly eroded me in such a way that, even a meaningless call surprisingly knocks me.)

Ek Zara Dam Leney Ki Qeemat mein Jaan Deni Padi

Zindagi Ka Tajruba Mera Bada Mehanga Pada

(Had to taste the death just for the sake of ordinary life, the business of living costed a lot to me.)

Look at the components of thought process that Safeer has taken into account in order to create his base of Ghazals. Dancing with the rhythm of death, living in dream, slowly eroded life, getting surprised by meaningless calls, lightness of life and tasting the elixir of death for the sake of low-priced life. Perhaps this maturity of Safeer Sddiqui in an immature literary career has stirred up a great fiction writer, critic, poet, translator, educator, professor, and orator of our time like Khalid Jawed to write 11-page appreciation for this anthology of Safeer Siddiqui. Professor Khalid Jawed pens in his foreword:

“This is to be noted that death or dream or suicide does not come in Safeer’s ghazals in a romanticized form, they come very straightforward just like a fine aspect of standard existence, this is not like scolding restfulness nor the despair or helplessness, this is the insanity that according to Pascal, has been written only in the fate of artists, poets and writers.”

But beautifying death and dream is no new in long and rich tradition of Urdu poetry. The theme has a well-connected chain from Mir, Ghalib to Fani Badayuni, Nasir Kazmi and of course Jaun Elia. All of them have already described death and dream in their own way of creative art. Mir Taqi Mir says:

Ibteda Hi Men Mar Gaye Sab Yaar

Ishq Ki Kon Inteha Laaya

(Every lover died just in the beginning; none reached the climax.)

Ghalib outlines the lifelong process of death in his own style:

thā zindagī meñ marg kā khaTkā lagā huā

uḌne se pesh-tar bhī mirā rañg zard thā

(Entire life was disturbed by fear of death, even before flying my color was cadaverous.)

The Urdu poet ofisolated perspective and most celebrated Shayer of late 20th century, Jaun Elia marks out the fear of death in such a simple way that it also can be the best example of ‘multum in parvo’ (a great deal in a small space) which is the first and foremost saliant feature of Urdu Ghazal:

kitnī dilkash ho tum kitnā dil-jū huuñ maiñ

kyā sitam hai ki ham log mar jāeñge

(How pretty you are! How joyful am I! irony is that we shall die.)

Then what is the relevance of Safeer Siddiqui’s poetry creation? The answer lies within the question itself. His art is taking forward the unique tradition of Urdu Ghazal. After going through the couplets of Mir, Ghalib and Jaun Elia, read this couplet by Safeer, you will find him a true successor of his forerunners:

Dhali Jo Shaam to Sab Apne Apne Ghar ko Chale

So Hum Bhi Maut Ka Darwaza Khat-Khatane Lage

(As evening falls, everybody returns back to home, what do I do, so I started ringing the doorbell of death.)

Note: All poetic and other translations in this review are done by reviewer himself.

The Reviewer, Wasim Ahmad Alimi is a translator and a Junior Research Fellow (JRF) at Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi.

About the Book

Book Name: Khawabon Ke Marsiye (poetry collection)

Author: Safeer Siddiqui

Pages: 126

Published by: Creative Star Publications

Price: 160 Check out the book on Amazon: http://surl.li/bqpip

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Role of Urdu in Historic Journey of Jamia: the Study of forgotten aspects

[You will, no doubt, be surprised to learn that everyone who participated in foundation of Jamia was also somehow associated with Urdu language and literature]

By: Wasim Ahmad Alimi

(Junior Research Fellow, JMI, New Delhi)

Jamia Millia Islamia was established on 29th October, 1920 at Aligarh, subsequently shifted to where it is now today. Mahatma Gandhi and Jawahar Lal Nehru left no stone unturned to support Jamia Millia Islamia since its emergence. You will, no doubt, be surprised to learn that everyone who any how participated in foundation of Jamia was also somehow associated with Urdu language and literature.The founders of Jamia Millia Islamia Maulana Mahmood Hasan, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jouhar, Hakim Ajmal Khan, Abdul Majeed Khawaja were originally eminent Urdu writers and poets. Their contributions to Urdu language are never forgettable. Maulana Mahmood Hasan was a famed Islamic scholar and at the same time he was also a literary craftsman of Urdu. One of its founders, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar was a distinguished poet and Journalist. In the same way, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Abdul Majeed khwaja both were acclaimed Urdu poets. Among the founding members of Jamia, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, was a prominent Urdu scholar whose beautiful writings of Urdu prose sometimes compared to divine words. One may witness the same while reading his collection of letters titled as Ghubar-e- Khatir. Dr Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari was also a great lover of Urdu language.

The Cherishers of Jamia Millia Islamia Dr Zakir Hussain, Prof. Mohammad Mujeeb and Dr Syed Abid Hussain were the greatwordsmiths of Urdu. Dr Syed Abid Hussain had translated a dozen of books from English and German to Urdu. He translated Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru’s Book Glimpses of World History, Discovery of India and An Autobiography in Urdu. Dr Abid Hussain had also translated Mahatma Gandhi’s world-renowned book My Experiment with Truth and one of Rabindra Nath Tagore’s books in Urdu language. These books were published from Maktaba Jamia limited, a publishing house of Jamia Millia Islamia.

Professor Mohammad Mujeeb was an impactful scholar, philosopher and Urdu playwright. His plays KhanaJangi,(Civil War) Hubba Khatoon,(The Lady Hubba) Kheti, Anjaam, Heroine ki Talaash, and Doosri Shadi are known as the basic Plays of Urdu literature. He was great fan of legend Ghalib.

Dr Zakir Hussain whose tireless services to Jamia is as obvious as sunshine, was also very passionate lover of Urdu language and literature.His book Abbu Khan Ki Bakri is considered a significant piece of Children Literature.

All those who nurtured Jamia had a dream to focus on Urdu language and literature and therefore they tried their best to glorify Urdu by their possible writings. And so that this dream may come true, Maktaba Jamia was founded in 1923. Under this publication House, myriads of valuable Urdu books written by great Urdu scholars of Undivided India and widely circulated. In which Mahatma Gandhi, Jawahar Lal Nehru, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Prem Chand, Firaaq Gorakhpuri, Majnu Gorakhpuri, Ranjindra Singh Bedi, Ismat Choghtai, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Qurratul Ain Haider and Ali Sardar Jafri’s works worth mentioning here. Maktaba Jamia started issuing premier and prestigious monthly magazines Payam-e-Taleem in 1923 for Children and Kitab Numa for elderly scholars in 1926 which are regularly being issued even today.

A world fame journal, Resala Jamia is also being published from Zakir Institute of JMI setting the milestones for Urdu literature. The well-known Urdu Short Story ‘Kafan’ by Munshi Premchand was originally published in the same journal.

Dr Zakir Hussain Central Library of JMI is known all over the world for its rare collection of books and manuscripts and has an attraction for the researchers from every corner of the world.

Department of Urdu since its initial days from 1972 is playing vital role in nourishing Urdu Language, literature and research across the nation. Prof. Gopi Chand Narang, Prof. Unwan Chishti, Prof. Mohammad Zakir and Prof. Shamim Hanfi have been much celebrated teachers and great literary persons of this department. They are known for their valuable academic works everywhere Urdu is being studied and taught. Professor Muzaffar Hanfi, Prof. Hanif Kaifi, Prof. Shamsul Haque Usmani, Prof. Khalid Mahmood and Prof. Sharper Rasool are also extraordinary teachers of the department. Some of the great name like Professor Ralf Russel, Professor Shamsur Rahman Farooqi, Qurratul Ain Haider, Ashok Vajpaee had been associated with department as visiting Faculties.

Recently in 2012, Ministry of Culture, Govt of India, commemorating 150th birth anniversary of Rabinra Nath Tagore, had assigned Urdu Department a historical work “Tagore Research and Translation Scheme”. Under this project, 13 books were published, some of them were translation of his original works and some were noted as research works on him. His Nobel awarded Book Geetanjali and venerable novel Gora, his short stories, memories, dramas were translated and published. Under this scheme, several lectures, seminars, workshops and cultural programmes were arranged by Urdu Department. The set of all books were presented to his Excellency Parnab Mukherjee (then president of India) who expressed his immense pleasure and satisfaction.

Even today, most of the faculty members’ research and creative works are much appreciable and more than 500 scholars and students are associated with the department. Jamia had, have and will have a firm relation with Urdu.

1 note

·

View note