#WITHIN A BUDDING GROVE [VOLUME 2]

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Does Tumblr have a post tag limit?

#Full text of “In Search Of Lost Time (Complete Volumes)”#CENTAUR#MARCEL PROUST#In Search of Lost Time#[ volumes 1 to 7 1#Marcel Proust#IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME#[VOLUMES 1 TO 7]#Original title: A la Recherche du Temps Perdu (1913-1927)#Translation: C. K. Scott Moncrieff (1889-1930) - vols. 1 to 6#Sydney Schiff (1868-1944) -vol. 7#2016 © Centaur Editions#[email protected]#Table of Contents#SWANN’S WAY [VOLUME 1]#Overture#Combray#Swann in Love#Place-Names: The Name#WITHIN A BUDDING GROVE [VOLUME 2]#Madame Swann at Home#Place-Names: The Place#Seascape#with Frieze of Girls#THE GUERMANTES WAY [VOLUME 3]#Chapter 1#Chapter 2#CITIES OF THE PLAIN [VOLUME 4]#Introduction#Chapter 3

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What best remind us of a person is precisely what we had forgotten (because it was of no importance, and we therefore left it in full possession of its strength). That is why the better part of our memories exist outside us, in a blatter of rain, in the smell of an unaired room or of the first crackling brushwood fire in a cold grate: wherever, in short, we happen upon what our mind, having no use for it, had rejected, the last treasure that the past has in store, the richest, that which, when all our flow of tears seems to have dried at the source, can make us weep again. Outside us? Within us, rather, but hidden from our eyes in an oblivion more or less prolonged. It is thanks to this oblivion alone that we can from time to time recover the person that we were, place ourselves in relation to things as he was placed, suffer anew because we are no longer ourselves but he, and because he loved what now leaves us indifferent. In the broad daylight of our habitual memory the images of the past turn gradually pale and fade out of sight, nothing remains of them, we shall never recapture it. Or rather we should never recapture it had not a few words been carefully locked away in oblivion, just as an author deposits in the National Library a copy of a book which might otherwise become unobtainable.”

― Marcel Proust, Within a Budding Grove, Part 2: Remembrance of Things Past Series, Volume II

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I used to try planning out my reading by making like a schedule/ordered list of what I'd read in hopes that it'd help me more consistently actually get through things as opposed to my usual mo of floating in and out of the six books that may be in the rotation that I'd chaotically be making my way through at any given point lucky if I ever eventually finished even one of them, but obviously the planning method didn't work and more importantly it didn't dispel the nagging anxiousness that I was falling behind (behind what or whomst I can't exactly say but it pervades everything doesn't it) and that I'd never read enough or the right things and certainly not all of the things I wanted to eventually read (which no one is ever able to do of course but like my particular methods seemed to condemn me to failing even more spectacularly in that regard) and even the things that I technically did complete I probably actually didn't adequately understand or feel or experience them I probably missed the Point entirely and wasted my time effort and disappointed/betrayed the book and the author and all of the readers that did in fact Get It and probably God too, so like if all of that's there either no matter what my particular reading habits are I might as well abandon myself to my natural disorganized chaos because at least that way I'm not unnecessarily enforcing and furter troubling myself with further regimentation of the unnatural linear time that oppresses us all so and that I apparently am even less able to handle than most people BUT having said all that this summer marks five years since I read my first Virginia Woolf novel is since the first page of To The Lighthouse cracked me right open and I want to make sure to reread it and also I want to read at least the first volume of her Diary and hopefully make that a consistent thing over the next few Summers until I'm through, it's still a Planned/Scheduled thing but I'm actually excited for to and it's part of sort of a cyclical returning movement through time both in terms of the seasons and in looping back to TtL so I'm excited and I think it'll be ennervating and worthwhile hopefully

#ibalso wajt to pick back up w/within a budding grove#so hopefully reading 1-2 volumes of that every summer can be an ongoing thing lol

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 1 (33b): the Mind of Wabi-Chanoyu in Poetry (part 2): the Poem Discovered by Rikyū.

33b) And again, Sōeki, because he had found one more poem, always wrote the two verses down together, believing them [to reveal the true mind of wabi-chanoyu]¹.

From the same collection², Ietaka's [家隆]³ verse⁴:

hana wo nomi matsuran hito ni yamazato no, yukima-no-kusa no haru wo mise-ba ya

[花をのミ待らん人に山ざとの、 雪間の草の春を見せばや]⁵.

This [poem] should [always] be added [to the one selected by Jōō].

The people of this world [are always wondering]: “on that mountain over there, in yonder grove, the flowers -- when, oh when will they begin to bloom?⁶”

Morning and evening they search [for these flowers and colored leaves] outside [of themselves]⁷, while failing to understand that those flowers and colored leaves are also within their own hearts⁸: [they] are only taking pleasure in the [fleeting] colors⁹ that appear before their eyes.

In the mountain village, as also in the tomaya by the bay, is [found] the same quiet abode⁹. [At the end of] last year, the whole of the year's flowers and the colored leaves, both¹¹ were completely buried by the snow [and so we can now start anew]. Coming to the empty mountain village, we can finally live in quietude: this is the same idea as the tomaya by the bay.

Besides this [opportunity to live in serenity], it is from that place where nothing exists that a feeling of spontaneity will appear in everything one does as host¹³ -- naturally and continuously¹⁴. It is like [the dormant landscape] buried under snow, from which the yang energy arises as spring advances -- so that surely, within the snow here and there, pale-green herbs begin to grow, pushing their two leaves and three leaves upward [through the snow]: without [needing to] exert [any external] force, [we] are [naturally] able to arrive at the authentic [expression of our samadhi] -- this is the way we should understand the example [described in this poem].

As for the Way of Poetry, it [surely] has its own [way of understanding the] details [of such things]. But with respect to this pair of poems, the [impressions] that have been carefully set down here accord with what was heard regarding the way [these poems] were understood in Jōō's and Rikyū's Way of Tea¹⁶.

[Considered] like this, [Jōō’s and Rikyū’s interpretations] reveal a deep aspiration for the Way¹⁶, and an enlightenment that surpasses all others¹⁷. The foolish monks [of the present day]¹⁸ are unable to equal [the samadhi achieved by these two tea masters]. Truly, we must venerate and appreciate such men of the Way¹⁹. We must wonder if this so-called “Way of Tea” might really be just another name for the Way of Enlightenment of the Patriarchs and the Buddhas?²⁰

How truly, marvelously commendable!²¹

_________________________

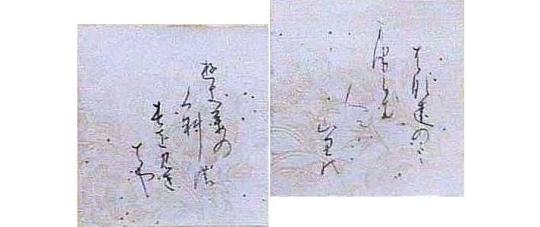

◎ A nineteenth century rendition of the poem quoted in the text of this entry, written on a pair of miniature shikishi [色紙]* cut from a piece of Chinese paper (kara-kami [唐紙]). This kind of arrangement is called tsugi-shikishi [繼色紙].

The calligrapher has not been identified. ___________ *Each of which measures 4-sun by 3-sun. The way a piece of ryōshi [料紙] was cut into standard-sized pieces for use as a medium on which poems might be inscribed was explained in the previous post. These tsugi-shikishi illustrate the way that a poem is traditionally divided across the two pieces of paper (with the kami-no-ku [上の句], which consists of three lines of 5-7-5 syllables, is usually written on one piece, while the shmo-no-ku [下の句], two lines of 7-7 syllables, is written on the other).

¹Shinzerareshi nari [信ゼラレシ也].

Shinzuru [信ずる] means to believe in (something). It is being used in the sense of “believe in God.” In other words, have an unshakeable faith that something is true.

Since the topic of this entry is wabi-chanoyu no kokoro [ワビ茶の湯のこころ], it was not necessary to repeat it here.

The statement means that Rikyū believed that the two poems (perhaps taken together) revealed the secrets of the mind of wabi-chanoyu.

²Dō-shū [同集].

This means “(from) the same collection,” and refers to the Shin Kokin Wakashū [新古今和歌集], where the first poem (by Fujiwara no Sadaie) is found.

However, and oddly, this poem is not included in the Shin Kokin Shu. Rather, the “published version*” is found in a private collection of Ietaka's poetry, the Mi-ni Shū [壬二集] (more will be said about this in the next footnote)†. ___________ *This refers to the final version of the poem, the one that was circulated among Ietaka’s contemporaries, and handed down to future generations (usually in hand-copied manuscript editions, rather than printed books). Occasionally there are minor differences between the “printed” version and the original -- since the original version was produced (under a certain amount of duress) during a poetry competition, which the poet sometimes “cleaned up” afterward (if the poem was received positively by the judges and critics, making it worthy of giving to a wider audience, and preserved for posterity).

†The poem was originally composed as one of Ietaka’s entries during an uta-awase [歌合] competition, and was probably first circulated in the minutes of that gathering.

³Ietaka [家隆].

This refers to Fujiwara no Ietaka [藤原家隆; 1158 ~ 1237]*, a contemporary and relative of Fujiwara no Sadaie, and a respected poet†.

Ietaka held the junior grade of the Second Rank (ju-ni-i [���二位]), and served as the minister who oversaw the management of the Imperial Household (ku-nai kyō [宮内卿]). __________ *The portrait of Ietaka shown above comes from a Meiji period book, and so is highly stylized. It does not appear as if any contemporaneous portraits of Ietaka have survived.

†Together with Sadaie, Ietaka was one of the compilers of the Shin Kokin Wakashū [新古今和歌集] -- though none of Ietaka’s poems were included in that anthology.

As I mentioned in the previous note, it seems that this particular poem was originally submitted as one of Ietaka’s entries during a poetry competition held in Kenkyū 3 [建久三年] (1192), a gathering that has come to be immortalized as the Roppyaku-ban Uta-awase [六百番歌合] (“the Poetry Competition in Six-hundred Innings”). During this poetry meet Ietaka competed on the side of the Right (u-hō [右方]), while Sadaie also participated, but on the side of the Left (sa-hō [左方]).

The poem was also subsequently included in a private (3-volume) collection of Ietaka’s best verses (works in this genre are referred to as shi-ka shū [私家集]), usually known as the Mi-ni Shū [壬二集] (the name comes from one of Ietaka's nicknames: Mibu ni-i [壬生二位]). (This collection is also sometimes referred to as the Gyoku-gin Shū [玉吟集].)

⁴Uta [哥].

The kanji* ka [哥], which can also be pronounced uta, means “elder brother.” It was apparently used as a shorthand form of the kanji ka, uta [歌], which means “poem” (literally, the kanji means a song or chant: the types of poems originally described by this word -- the tan-ka [短歌]† -- were intended to be chanted, never just read silently -- it is said that their true meaning can only be fully appreciated when they are changed out loud). ___________ *In fact, this kanji has rarely been employed in Japan for its literal meaning. It has historically been used as an abbreviation for the homophonous ka, uta [歌], which means “poem,” “song.”

†Tan-ka [短歌] (which means “short verse”) are poems composed of 31 syllables (in the format 5-7-5 7-7). Tanka is another name for the wa-ka [和歌] (which means “Japanese-style poem,” and was originally a generic term for all styles of Japanese poetry).

⁵Hana wo nomi matsuran-hito ni yamazato no, yukima-no-kusa no haru wo mise-ba ya [花をのミ待らん人に山ざとの、雪間の草の春を見せばや].

The poem may be translated: “to those people who are waiting only for the [cherry] blossoms: the herbs [flowering] within the snow in a mountain village -- that is the place to look for ‘Spring.’”

Hana wo nomi matsuran-hito ni [花をのミ待らん人に]: hana [花], in classical Japanese literature*, is a reference to the cherry blossoms†; nomi [のみ] is the literary equivalent of dake [だけ] or bakari [ばかり], and means “just (this),” “nothing other than (this),” “nothing but (this);” matsuran-hito [待��ん人] means a person who is waiting (for something), and in classical poetry the word often implied a state of impatient longing (as of a woman‡ waiting for her lover to arrive); and ni [に], which means “to,” refers to the object (introduced by the particle wo [を]) of the second phrase, mise-ba [見せ場].

Yamazato no yukima-no-kusa no haru [山ざとの雪間の草の春]: yamazato [山里] means a mountain village; yukima-no-kusa no haru [雪間の草の春] means “the spring of the plants-within-the-snow.” According to poetic scholars, Ietaka’s intended mental image was what is conveyed by the above photo**.

Mise-ba ya [見せばや]: miseba [見せ場] means “a/the place to look” (and so the expression is often used idiomatically in modern Japanese†† to mean a highlight, in the sense of a decisive scene or climactic moment -- something that must be looked at); ya [や] functions as a sort of exclamation point, since the argument (that the people waiting for the cherry blossoms should rather look at the plants buried in the snow) is unexpected and startling. ___________ *In Japanese poetry, the word hana [花] usually implies the cherry blossom. In Chinese poetry, however, it usually means the tree-peony.

†The cherry blossoms flower from late spring into early summer (hence the occasional complaints regarding the late-flowering varieties that are found in Heian literature, since these late blossoms contravened the ingrained cultural sensibilities).

In fact, the cherry blossoms generally begin to bloom two weeks after the buds of the hana-suou [花蘇芳], the Oriental Red-bud tree (Cercis chinensis), change color (which indicated the time when the ro should be closed, and the furo brought back into use).

‡Unfortunately (for modern feminist sensibilities), in ancient times women generally remained in their own homes (even after they were married), with their lover or husband coming for amorous/conjugal visits when circumstances permitted (or the pangs of passion demanded). This remained a poetic convention even after it became common for a woman to move into her husband’s residence after marriage.

**The flowers generate heat as they elongate and begin to bloom, thus melting the snow around them enough to allow them to flower more or less unmolested. Note that the snow is compacted and “old,” which is another indication of the advent of Spring.

This plant, known as fuku-ju-sō [福壽草] (Adonis amurensis) -- which means “the herb of good fortune and long life,” another indication of its intimate connection with the New Year -- always begins to flower around the time of the Lunar New Year (and then blooms again, on much-elongated stems, after the snow has melted away). It, thus, is a better harbinger of Spring than is the cherry blossom, which flowers at the end of the season. This poem seems to turn on the idea that it is better to appreciate things when they are nascent (anticipation), rather than at their end (regret).

Furthermore, the fuku-ju-sō presents an image of strength, perseverance, and ultimate victory, while the cherry blossoms have always been considered fickle, inconstant, and weak (since their petals begin to fall while they are blooming, even when prodded by nothing more than a gentle spring breeze), and Ietaka’s poem also seems to be comparing these attributes as well, leading to his ultimate preference for the former.

††Care must always be taken by the modern reader not to apply contemporary usages to the words in classical writings. In pre-Edo times, the kanji were generally used much more literally: miseru [見せる] means to show, indicate, point out (something); ba [場] means a field, a spot (as in “this is the spot”), a place.

⁶Sejō no hito-bito soko no yama ・ kashiko no mori no hana ga, itsu-itsu saku-beki kado [世上の人々そこの山・かしこの森の花が、いつ〰さくべきかど].

Seijō no hito-bito [世上の人々]: seojō [世上] means “in the world,” “in society,” and refers to the mundane world (the world that Buddhism recommends that we eschew); hito-bito [人々] means the people. Thus, “ordinary people,” people who have not been enlightened. Such people are always obsessed with ephemeral matters that are inherently insignificant and meaningless.

Kashiko no mori no hana ga [かしこの森の花が]: kashiko [かしこ] means there (especially when pointing with the finger), over there, yonder; mori [森] is usually translated “forest,” but here does not necessarily mean anything so extensive, hence grove; and once again, hana [花] refers to "cherry blossoms" -- with ga [が] indicating that it is the subject of the whole compound phrase -- the subject not only of “kashiko no mori,” but also of “soko no yama” (that mountain over there) as well*.

Itsu-itsu sakubeki kado [いつ〰さくべきかど]: itsu [何時] means “at what time(?),” so doubling it makes their query emphatic, or possibly introduces a sense of urgency; saku [咲くべき] means to bloom, so saku-beki [咲くべき] means should open; kado [かど] is a colloquialism which indicates doubt.

The “worldly people” are concerned about when the cherries will bloom because this will give them the opportunity to go on a hana-mi [花見] outing, where they can eat and drink and enjoy themselves (usually to the point of excess). __________ *Grammatically, the grove is not on the mountain to which the second half of the phrase refers. They are two different places where the cherry blossoms might be found. This is the reason for the interpunct (“・”).

⁷Ake-kure soto ni motomete [あけ暮外にもとめて].

Ake-kure [明け暮れ] literally means “when it is getting light, when it is growing dark,” and means “morning and evening” (and, by extension, “day and night” -- in other words, “constantly”).

Soto ni motomete [外にもとめて]: soto ni [外に] means externally, outside of (oneself); motomeru [求める] means look for, search for.

⁸Iro [色].

The word iro [色] (“color”) is frequently employed as a metaphor for worldly phenomena, especially things of a sensual nature (which are frowned upon by Buddhist monks).

⁹Kano hana-momiji mo waga-kokoro ni aru koto wo shirazu [かの花紅葉も我心にある事をしらず].

Kano [かの]* means “that,” “(over) there,” “those.”

Waga-kokoro ni [我心に] literally means “within my own heart.”

Shirazu [知らず] means “not knowing about (something);” “to be ignorant of (something).” ___________ *In the modern language, the pronunciation ano [あの] seems to be preferred.

¹⁰Sabita jūkyo [サビタ住居].

Sabitaru [寂びたる] means quiet, soundless, still, silent; and has the nuance of being free of turmoil, uproar, or confusion (and what these ideas mean in a Buddhist sense).

Jūkyo [住居] is a residence, house, dwelling, abode.

¹¹Kyonen hito-tose no hana mo momiji mo [去年一トセノ花モ紅葉モ].

Hito-tose no hana mo momiji mo [一年の花も紅葉も] means one year's (flowers and colored leaves), the whole year's (flowers and colored leaves).

The meaning is (while attempting to use the imagery provided by the poem) that the past has buried the past. The past is past.

¹²Sabi-sumashita made ha [サビスマシタマデハ].

There is an omission in this line. It should read sabi-sumashitaru made ha [寂び住ましたるまでは] which means “until one can live quietly....”

¹³Onozukara-kan wo moyōsu-yō-naru shosa [ヲノヅカラ感ヲモヨホスヤウナル所作].

Onozukara-kan [自ずから感] means spontaneous feelings.

Moyōsu-yō-naru shosa [催す様なる所作]: moyōsu [催す] means to host (a gathering), to hold (a gathering), to throw (a party); yō [様] means “like that” (referring to whatever word it follows); naru [成る] means “to do;” and shosa [所作] means gestures, behavior. So, this expression means “the things one does when hosting (a gathering).”

¹⁴Ten-nen to ha tsure-zure aru ha [天然トハヅレ〰ニアルハ].

Ten-nen [天然] means naturally.

Zure-zure [連々]* means “successively,” “continuously,” “in an uninterrupted stream.” __________ *Tanaka Senshō's text has soba-soba [端々] here, which means “here and there,” “scattered.”

“Things arising spontaneously, here and there” certainly is a valid Zen sentiment that is the topic of many well-known kōan [公案].

¹⁵Chikara wo kuwaezu ni shin-naru-tokoro no aru dō-ri ni torare-shi nari [力ヲ加ヘズニ真ナル所ノアル道理ニトラレシ也].

Chikara wo kuwaezu [力を加えず] means “force is not added” -- in other words, “without applying (any external) force.”

Shin-naru-tokoro [真成る所] means “the place of truth;” “the place where the truth is found.”

Aru dō-ri ni [有る道理に] means “there is a/the reason.”

Torare-suru [取られする] means “to take (something a certain way;” “take hold of (an idea).”

Thus, without adding any external force*, we naturally arrive at the place where the truth is able to expresses itself -- this is how we should understand the example of the green herbs pushing their way upward through the snow. __________ *The “yang energy” appears spontaneously from within the earth.

¹⁶Kayo ni michi ni kokorozashi-fukaku [かやうに道に心ざしふかく].

Michi ni kokorozashi-fukaku [道に志深く]* means “to harbor a deep aspiration for the Way.” __________ *Kokorozashi [心ざし] is an erroneous (or possibly phonetic) rendering of the word kokorozashi [志].

¹⁷This assessment is usually interpreted (by modern-day scholars) as referring to Rikyū alone. However, from the context, it would appear that Sōkei (or whoever wrote this passage) is saying that both Jōō's and Rikyū's apparent state of insight (enlightenment) might be so described.

In fact (the propaganda narrative written and directed by the Senke aside), this would tend to agree with early Edo ideas, especially those held by members of the governing class, where (relying on machi-shū narratives that arose in the immediate aftermath of Rikyū's seppuku) the chanoyu of Jōō's middle period was revered as highly as anything attributed to Rikyū (and where most of such attributions were borrowed from things actually done by Jōō or Furuta Sōshitsu, and only credited to Rikyū).

The fact that Katagiri Sadamasa (Sekishū), whose original lineage took him back to Rikyū (through Kuwayama Sōzen, who was Sen no Dōan's principal disciple), chose to devote the last years of his life studying Jōō's chanoyu is significant -- and revealing of the sensibilities of that age.

��⁸Gu-bō tō ga oyobu-beki ni arazu [愚坊等が及ぶべきにあらず].

Gu-bō tō [愚坊等]: gu-bō [愚坊] means “foolish monk,” as we have seen before in Book One of the Nampō Roku, and Nambō Sōkei used it when referring to himself. Adding tō [等] to a noun essentially makes it plural*. Thus, gu-bō tō [愚坊等] means something like “the foolish monks (of the present day).”

Sōkei was the shuso [首座] (the monk who is in charge of controlling the monks in the temple system) of the Nanshū-ji, and so he would have been a reliable judge of the abilities and attainments of those of his contemporaries who were under his charge (and thus would be able to make a reasonable extrapolation to the monks of his generation more generally).

Oyobu-beki [及ぶべき] means “should be equal (to),” “should be the same (as).”

Arazu [有らず] means “(this kind) does not exist,” “there are none (such).” ___________ *Tō [等] actually designates a class or group of closely related (or identical) things. Thus, gu-bō tō [愚坊等] literally means foolish monks of this class. The kanji is also pronounced -nado [など = 等], where it literally means “and the like,” “and things of that sort.”

¹⁹Makoto ni tattobu-beku arigataki dō-jin [まことに尊ふべくありがたき道人].

Makoto ni [誠に] means truly, honestly, truthfully speaking.

Tattobu-beku [尊ぶべく]: tattobu [尊ぶ] means to respect, to revere, to venerate, to honor; -beku [べく] means should.

Arigataki dō-jin [有り難き道人] (or arigatai [有り難い道人], in the modern language) means things like “kind,” “favorable,” “blessed,” “welcome;” dō-jin [道人] means a Man of the Way. Thus, “a wonderful Man of the Way;” or possibly something like “a Man of the Way for whom we are deeply thankful.”

²⁰Cha no michi kado omoeba sunawachi, soshi-futsu no go-dō nari [茶ノ道カトヲモへバ則、祖師佛ノ悟道也].

Cha no michi kado omoeba [茶の道かど思えば]: cha-no-michi [茶の道] means the Way of Tea; kado [かど] is a colloquialism which indicates doubt; omoeba [思えば] means “if I think (something),” “I wonder if....” Thus “when I think about the Way of Tea....”

Sunawachi [則ち] means “namely,” “that is to say” -- in other words, “another name for....”

Soshi [祖師] means “the patriarchs” -- the founders of the different schools and sects of Buddhism.

Futsu [佛] means “the Buddha,” or “the Buddhas” (depending on how one understands the nature of the Buddhist deities*).

Go-dō [悟道] means the Way of Satori; the Path of Enlightenment†. __________ *Some Buddhist scholars consider the various named Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to represent different aspects of Siddhartha Gautama's mind.

And many would argue that there are no such entities as “deities” in Buddhism.

†Satori [悟り] means enlightenment.

²¹Shushō-shushō [殊勝〰].

Shushō [殊勝] means commendable. Doubling the word amplifies the complement.

———————————————————————————————————

This second part of the entry 31 clearly betrays the influence of the ideas that were eventually codified in the Zen-Cha Roku [禪茶録] -- which is also true for other portions of Book One of the Nampō Roku that are linguistically similar to this one*.

The language is also consistent with previous entries that have been judged spurious (for example, large sections of the post, entitled Nampō Roku, Book 1 (31): No-gake [野懸け]¹ (part 1) -- the Daizen-ji Mountain Chakai), despite the fact that this is one of the best known (and most beloved) entries in the Nampō Roku.

Furthermore, and contrary to the assertions made in the present entry, no copies of either of these poems have ever been attributed to Rikyū in any of the kaiki from the late sixteenth century down to the present†. This would not, in and of itself, prove that such copies never existed. But when taken together with the fact that a number of kakemono featuring one or the other of these poems -- written by important political or tea figures over the course of the Edo period -- appear with a certain regularity in the kaiki, the absence of even one instance where the writing is attributed to Rikyū (even when the honshi [本紙] is not actually signed -- as was usually the case with shikishi [本紙]) is certainly disturbing.

This all begs an answer to the question of why such a spurious essay has garnered (and sustained) the recognition that it has‡. And the only possible answer is that it filled a philosophical void -- a void that exists in Rikyū’s actual writings -- and which can be expressed as a desire for information that shows the practitioners of chanoyu what and how they are supposed to think. The absence of such modi operandi was, at least on Rikyū’s part, apparently quite deliberate -- since, for him, chanoyu seems to have been intended as a vehicle through which the practitioner’s own nature was expressed (a revelation of the state of his samadhi), which was to be governed by as few exogenous rules as possible. This, of course, was bound to come into conflict with the Edo period’s social conventions, where everybody was told everything that they were supposed to believe, and say, and do, and where dissenters and nonconformists were usually punished severely.

This entry conforms closely to certain machi-shū strains of thought, which eventually took their final form from the teachings of Takuan Sōhō (best known to us as they were ultimately expounded in the Zen-Cha Roku); and, since it was this same group of machi-shū practitioners that the Tokugawa bakufu set up as the official heritors of Rikyū’s chanoyu, it was perhaps necessary to have a strongly worded passage present in this collection of writings that were supposed to reflect and reveal the secrets of Rikyū’s own chanoyu.

That this section came to be regarded as (and remains) one of the most influential essays in the Nampō Roku appears, then, to have been by deliberate and calculated design. Even as it remains at odds with the usual inclination toward luxury and ostentatious display (and the secret teachings and money) that were (and remain) its counterpoint in the version of chanoyu that has been handed down to us from the Edo period. ___________ *Which suggests that they were authored by the same person, or at the behest of the same organization -- who, due to the obvious and inherent differences in the idiom of the language, can not reasonably be identified with either Sen no Rikyū or Nambō Sōkei (even when we allow that such authentic sections were also reworked, often extensively, by Tachibana Jitsuzan -- whose purpose appears to have been, at least for the most part, to modernize the language in which the entries were written).

†Which contrasts with other kinds of things written by (or attributed to) Rikyū -- some of which are certainly authentic, while others are clearly forged copies (that strove to reproduce his writings faithfully), and others that are completely fraudulent. This includes several complete copies of the Chanoyu Hyaku Shu [茶湯百首] -- enough, in fact, to have given rise to the assertion that these poems were composed by Rikyū (rather than Jōō -- even though Jōō’s authorship can be verified historically by referring to the earliest manuscript collections).

‡This is especially disturbing when we consider that, during this same period, Rikyū’s own authentic writings and teachings were subject to unrelenting attacks asserting that they were fraudulent -- charges from which they have never been fully rehabilitated.

———————————————————————————————————

◎ This is the end of Book One of the Nampō Roku.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Austin Dam Failure Flood Zones

Downtown Austin is well protected from major flooding events thanks to our Highland Lakes system. The Highland Lakes were formed after constructing a chain of six major dams along the Colorado River between 1938 and 1951. However, what would happen to Austin if the dams did fail?

Congress St Bridge during 1935 Flood

Austin was flooded twice in the early 1900s due to local dam failures. Early dam projects had trouble trying to control the mighty Colorado and actually left the city impoverished for years afterwards. It took federal funds and the founding of the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA) to build the current system of dams that protect Austin.

What would happen if the dams that protect Austin were to fail again? Here’s the projections to give you some context on what would happen if the Tom Miller and Mansfield Dams failed, according to the LCRA projections.

Normal Austin Water Areas

Tom Miller Dam Failure

At-Risk if Tom Miller Dam Fails

$539 Million Dollars in Property

4,357 People in 1,995 Housing Units (2004 fig.)

21 Bridges

The Tom Miller Dam is located near Red Bud Trail in West Austin and is the upstream dam that forms Lady Bird Lake. If the Tom Miller Dam were to fail it would cause moderate flooding of downstream areas, namely some of Auditorium Shores and along Cesar Chavez. Past IH-35, areas normally occupied by small creeks will swell and expand to the natural banks for the Colorado and a large amount of Roy G. Guerrero park would be inundated.

Damage is largely mitigated due to the relatively low volume of water contained by the Tom Miller Dam. The dam is responsible for holding 21,000 acre-feet back, which is only 1.8% of the volume held back by Mansfield Dam.

Mansfield Dam Failure

At-Risk if Mansfield Dam Fails

$4+ Billion Dollars in Property

35,918 People in 13,382 Housing Units (2004 fig.)

108 Bridges

6 Fire & Police Stations

12 Schools, 1 Hospital, and 6 Toxic Sites

1 – Floodwaters would extend up to West 6th Street near Mopac 2 – Floodwaters would extend to Barton Creek Blvd 3 – Downtown would be flooded up to 5th – 7th Street 4 – East Austin would be flooded up 7th Street 5 – Floodwaters would extend to Riverside & Grove 6 – Floodwaters would extend to 12th & Airport 7 – Flooding would extend as far as Hwy 71 by ABIA

Mansfield Dam is located by 620 near Lakeway, West of Austin. It is the only dam meant to hold back floodwaters in the chain, making it incredibly important for Austin and downstream cities. If the dam were to fail it would unleash 1.1 Million cu. ft. of water per second.This high flow rate would also continue for a substantial amount of time due to the size of Lake Travis (1.1 Million acre-feet).

These projections take into account the subsequent failure of Tom Miller Dam since it cannot withstand the surge of floodwaters. Needless to say, Austin would be heavily affected by a flood of this magnitude, with the potential loss of life in the thousands and the large-scale destruction of Central Austin.

The shear destruction by the initial wave of water will be catastrophic. Depending on the size of the breach, a wall of water will be blasted out at speeds in excess of 1,000 MPH and could still be traveling at 50 MPH by the time it reaches Austin. In the Teton Dam failure, initial wave velocity was 1,090 MPH (1,960 ft/s) and the wave was 120 ft tall. The St. Francis Dam failure was an instantaneous failure and released an initial wave of water at 2,018 MPH (2,960 ft/s). These velocities are the result of massive amounts of pressure being created by the weight of the water.

The energy within a huge body of water moving at even 20 – 30 MPH are sufficient to obliterate most structures including high-rises and bridges. Even if a structure withstands the initial impact, it must also survive being subjected to continuous force from the waters rushing by, debris strikes, and the potential erosion of the foundation. As we saw in the FM 2900 bridge collapse, the water is more than capable of tossing around entire sections of a bridge like it was a raft.

Research & Source Links

LCRA Dams & Lakes LCRA Dam Failure Report (PDF) H20 Partners (Visuals) FEMA Dam Safety & Failure Report (PDF)

The post Austin Dam Failure Flood Zones appeared first on Lawnstarter.

from Gardening Resource https://www.lawnstarter.com/blog/texas/austin-tx/austin-dam-failure-flood-zones/

0 notes

Text

Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Android Tablets - Collection 'P'

COLLECTION 'P'

Download free eBooks to your Kindle, iPad/iPhone, computer, smartphone, or e-reader. The collection includes great works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, including works by Asimov, Jane Austen, Philip K. Dick, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Neil Gaiman, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Shakespeare, Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf & James Joyce.

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | T | U & V | W | Y & Z

Paine, Thomas - Common Sense iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Paine, Thomas - Rights of Man iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Paine, Thomas - The Age of Reason iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Pascal, Blaise - The Pensées iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Pascal, Blaise - The Provincial Letters Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Perrault, Charles - Cinderella Read Online Now Planck, Max - Eight Lectures on Theoretical Physics Read Online Now Plath, Sylvia - A Lesson in Vengeance Read Online Now Plath, Sylvia - Ariel Read Online Now Plath, Sylvia - Blackberrying Read Online Now Plath, Sylvia - Daddy Read Online Now Plath, Sylvia - Dream with Clam-Diggers Read Online Now Plato - Collected Works Read Online Now Plato - Three Illustrated Dialogues by Plato: Euthyphro, Meno, Republic Book I Read Online Now Plato - Symposium iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Plato - The Apology, Phaedo, and Crito of Plato iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Plato - The Republic iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Plutarch - Lives iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 1 iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 2 iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 3 iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 4 iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 5 iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - Tales of Mystery and Imagination Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Complete Poetical Works iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Raven (Illustrated by Gustave Doré) Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Poe, Edgar Allan - The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Popper, Karl - The Logic of Scientific Discovery Read Online Now Potter, Beatrix - The Tale of Peter Rabbit iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats Pound, Ezra - Canto I Read Online Now Pound, Ezra - Canto XVI Read Online Now Pound, Ezra - Cathay iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Pound, Ezra - Personae Kindle from Amazon Proust, Marcel - Swann's Way iPad/iPhone - Read Online Now Proust, Marcel - Within a Budding Grove Read Online Now Proust, Marcel - The Guermantes Way Read Online Now Proust, Marcel - Cities on the Plain Read Online Now Proust, Marcel - The Captive Read Online Now Proust, Marcel - The Sweet Cheat Gone Read Online Now Proust, Marcel - Time Regained Read Online Now Proust, Marcel - À la recherche du temps perdu Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now Pushkin, Alexander - Eugene Onegin iPad/iPhone - Kindle + Other Formats - Read Online Now

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | T | U & V | W | Y & Z

---------------------------------------------------------

Get your device :

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2TcjYtV

0 notes

Photo

I've been tagged by @raisingthemorrigan & @raggedpoet for the "20 Things About Me" So here goes: 1. I'm ambidextrous. 2. I'm a Capricorn Sun, Taurus rising, Aquarius Moon. 3. I once pet a baby deer in the wild. 4. I'm currently a Stay at Home Mama. It's the best job I've ever had, but my Boss can be a real cry-baby sometimes (yakky smacky doo) 5. I've been working with Tarot since 2006. 6. I've served on a jury for a murder trial. 7. I don't own a car, or have ever driven one. 8. I've climbed to the top of a Mayan pyramid. 9. My only tattoo is of a Tristero from The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon. 10. I have experienced all the "Clairs" at least once (Clairvoyance, Clairaudience, Clairsentience and Claircognizance) 11. I have a dangerously nerdy knowledge of all things David Bowie. 12. I like writing with foundation pens because they make me feel fancy. 13. I'm completely straight-edge: i.e. Don't drink, smoke, or do any of the fun stuff. 14. Mysterious Universe is my favorite Podcast. 15. I once saw a ghost when I was little. 16. I have a dangerous, artery-hardening love for cheese. 17. My favorite author is Dostoevsky. 18. I have one daughter, two cats, and a dog. They run wild around here. 19. I listen to a ton of Electronic Music: Bonobo, Efterklang, Perturbator, Tokimonsta, Carpenter Brut, mùm, etc. 20. I'm slowly plodding though all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, and currently in the home-stretch of Within a Budding Grove. 20 1/2. Here's a picture of my lovely mug. See, I'm not so mysterious now! 😊 Whew! That was fun! Do people read all of these things? I'm curious. I'm not going to tag anyone (unless you want to be tagged, in which case I have officially tagged you) because I think everyone has done this challenge already- and @raggedpoet and myself were the final holdouts 😊 #tarotcommunity #20questions #instagramchallenge

0 notes

Text

Week 2: Initial Thoughts on “Swann in Love”

The following was written a week ago; I was so taken by this text that the only thing that could distract me from it was the inherent need to record how taken I was with it:

I have just finished reading the first 60 pages of “Swann in Love”; it only took about five pages before a little sob, an intake of breath that could just as easily been a cry of pleasure as one of pain, escaped my mouth, and a decent amount of tears followed in the next 50 pages. It should be noted that I’m a bleeding heart, a sucker for love, and a terrific crier. Every movie I go to see, sad or not, I’m more than likely bawling at some point—I don’t even know why; I don’t ever cry when watching movies at home (which I do most nights a week), but the second I get in the theater the flood lets loose. Still, I didn’t expect to be so affected.

But a lot of my response to this, the most famed and well-known section of the novel, is highly personal in a way that won’t fade in a few days or a week. Because I read this thing when I was 20 years old, and then just two years later, I let myself fall into the same miserable trap that Swann does: Swann meets a woman who, while not necessarily attractive to him, is amenable to his desires; he spends time with her, while all the while entertaining other women and never thinking he could be attached to this one who holds so little charm for him; before long, habit has obliterated all he once identified himself as, and he plays the fool. It is a little startling to look back on my own experience, much the same, while rereading this section. It seems as impossible to me now that I should have fallen for it, as it would have seemed to Swann before he ever entered the household of the Verdurins.

I considered writing something about that relationship, my first serious one, in relation to my current reading experience, but the truth of it would come across as shit-talking. I’m not really bitter about it, and think of that person quite rarely. Suffice it to say that he did a number on me, and that his behavior was quite as crude as Odette de Crecy’s.

***

Since writing the above a week ago, I have read the majority of the rest of “Swann in Love”; I will complete it immediately after posting this—I would have finished sooner, but I have had some interesting developments in my life that I am trying to square.

I wrote down one quote from this section: “How readily he would have sacrificed all his connections for no matter what person who was in the habit of seeing Odette, even if she were a manicurist or shop assistant! He would have put himself out for her, taken more trouble than he would have for a queen.”

Is this not the very definition of love? We can put it in lofty, lovely terms, but in the end, it is about effort, it is about obsession, it is about a degree of care that is reachable under only one circumstance. It is power and weakness at the same time. It is a show of force and a shying away. It is so easily taken advantage of. I am beginning to wonder what I hope to achieve with this project as I immerse myself again in this world; as I begin to remember that this theme of the deception and corruption of others’ most sincere emotions is a major theme of this work. But then, I recall the aspects of those “others” that were equally deplorable. Is this novel about the fruitlessness of love? The inherently amazing beauty of it? The crass reality of it? My suspicion is that it is a complex amalgamation of all those things and many others. A maze I am about to incontrovertibly enter as I begin volume two, Within A Budding Grove.

#Marcel Proust#Proust#in search of lost time#a la recherche du temps perdu#putains#love#obsession#Swann#Swann in Love

0 notes