#Tulathromycin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

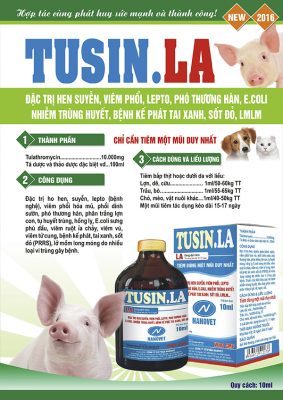

TUSIN.LA

Tên sản phẩm: Tusin.LALoại sản phẩm: Kháng sinh tiêm dạng Dung dịch & Huyễn dịchNhà sản xuất: nanovetKích thước: 10ml THÀNH PHẦN:Tulathromycin Công dụng: Đặc trị ho hen, suyễn, lepto, viêm phổi hóa mủ, phổi dính sườn, phó thương hàn, phân trắng lợn con, tụ huyết trùng, hồng lỵ, e.coli sưng phù đầu, viêm ruột ỉa chảy, viêm vú, viêm tử cung, bệnh kế phát, tai xanh, sốt đỏ, lở mồm long móng do…

View On WordPress

#bò#Bệnh Hô Hấp Chó Mèo#Bệnh Hô Hấp cho Chó#Bệnh Hô Hấp cho Dê#Bệnh Hô Hấp cho Gia Súc#Bệnh Hô Hấp cho Mèo#chó#gia súc#heo#Kháng Sinh#Kháng Sinh Nanovet#Kháng Sinh Tiêm#lợn#thú cưng#trâu#Tulathromycin

0 notes

Text

Exploring the Advantages of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals

0 notes

Text

Global Veterinary Anti-infectives Market Analysis 2024 – Estimated Market Size And Key Drivers

The Veterinary Anti-infectives by The Business Research Company provides market overview across 60+ geographies in the seven regions - Asia-Pacific, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, North America, South America, the Middle East, and Africa, encompassing 27 major global industries. The report presents a comprehensive analysis over a ten-year historic period (2010-2021) and extends its insights into a ten-year forecast period (2023-2033).

Learn More On The Veterinary Anti-infectives Market: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/veterinary-anti-infectives-global-market-report

According to The Business Research Company’s Veterinary Anti-infectives, The veterinary anti-infectives market size has grown strongly in recent years. It will grow from $5.09 billion in 2023 to $5.58 billion in 2024 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.6%. The growth in the historic period can be attributed to increasing pet ownership, prevalence of infectious diseases, advancements in veterinary medicine, rising awareness, government initiatives.

The veterinary anti-infectives market size is expected to see strong growth in the next few years. It will grow to $8.05 billion in 2028 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.6%. The growth in the forecast period can be attributed to continued pet population growth, emerging zoonotic diseases, globalization of pet trade, increasing veterinary healthcare expenditure. Major trends in the forecast period include technological advancements, increasing adoption of biologicals, integration of telehealth in veterinary services, focus on natural and herbal alternatives, expansion of e-commerce in veterinary pharmaceuticals, collaborations and partnerships.

An increase in pet ownership is expected to propel the growth of the veterinary anti-infectives market going forward. Pet ownership refers to owning a dog, cat, or other domestic pet at home. Pet are being adopted as increasing number of the young population are considering them as part of their family, some owners are adopting them for their compassion, loyalty and the to prevent loneliness. For instance, in February 2023, according to Chewy Inc., a US-based online retailer of pet food and other pet-related products, in 2021, approximately 977,202 pets found homes through adoption in the United States, marking the highest adoption rate in the past six years at 61%. Therefore, an increase in pet ownership is driving the demand for veterinary anti-infectives market.

Get A Free Sample Of The Report (Includes Graphs And Tables): https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/sample.aspx?id=7802&type=smp

The veterinary anti-infectives market covered in this report is segmented –

1) By Drug Class: Antimicrobial Agents, Antiviral Agents, Antifungal Agents, Other Drug Classes 2) By Species Type: Livestock Animals, Companion Animals 3) By Mode Of Administration: Oral, Parenteral, Topical 4) By Distribution Channel: Veterinary Hospitals, Veterinary Clinics, Pharmacies, Others Distribution Channels

Technological advancements are a key trend gaining popularity in the veterinary anti-infectives market. Major companies operating in the market are using advanced technologies to sustain their position in the veterinary anti-infectives market. For instance, in February 2021, Elanco Animal Health Incorporated, a US-based pharmaceutical company that manufactures drugs and vaccinations for pets and livestock launched Increxxa, the newly approved drug for livestock respiratory disease. Increxxa with its key ingredient being tulathromycin is delivered to the livestock in injection and targets the lungs' site of infection swiftly for fast action and a lengthy half-life, providing cattle more time to establish a strong defense. This product is designed for veterinary use and tulathromycin, the active ingredient in Increxxa, helps decrease the negative effects of bovine respiratory disease.

The veterinary anti-infectives market report table of contents includes:

Executive Summary

Market Characteristics

Market Trends And Strategies

Impact Of COVID-19

Market Size And Growth

Segmentation

Regional And Country Analysis . . .

Competitive Landscape And Company Profiles

Key Mergers And Acquisitions

Future Outlook and Potential Analysis

Contact Us: The Business Research Company Europe: +44 207 1930 708 Asia: +91 88972 63534 Americas: +1 315 623 0293 Email: [email protected]

Follow Us On: LinkedIn: https://in.linkedin.com/company/the-business-research-company Twitter: https://twitter.com/tbrc_info Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TheBusinessResearchCompany YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC24_fI0rV8cR5DxlCpgmyFQ Blog: https://blog.tbrc.info/ Healthcare Blog: https://healthcareresearchreports.com/ Global Market Model: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/global-market-model

0 notes

Photo

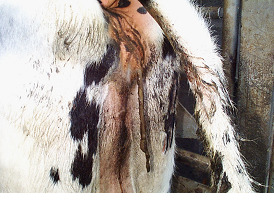

Leptospirosis Other names: Weill’s disease (severe form in humans) Cause: Leptospira spp (multiple serovars exist) Species: Swine, dogs, horses, cattle, humans. Many other species are also affected and/or asymptomatic carriers. Signs: Swine – abortion (usually in last 3 weeks of pregnancy), stillbirths, weak piglets that die soon after birth or grow slowly. Other than reproductive losses affected swine often appear healthy; anorexia, lethargy, and mild scours of a few day duration is sometimes seen. Dogs – Acute kidney injury that, if survived, may progress to chronic kidney disease. Acute liver disease. Icteris, increased bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, polyuria/oliguria/anuria, cylindruria, proteinuria, or glycosuria; azotemia, hyperphosphatemia, acidosis, hyperkalemia, neutrophilia, lymphopenia, monocytosis, and mild anemia, muscle pain, stiffness, weakness, trembling, reluctance to move, weight loss, fever or hypothermia, oculonasal discharge lymphadenopathy, effusions, and edema. Rarely bleeding disorders, uveitis, cough, dyspnea. Commonly fatal. Horses – recurrent uveitis, abortion (usually after 9 months gestation); occasionally, fever and acute renal failure Cattle – Most commonly abortion, stillbirth, increased services per conception, prolonged calving intervals, agalactia/blood-tinged milk. Often a large portion of the herd is affected. Less commonly, high fever, hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinuria, jaundice, pulmonary congestion, meningitis, death. Humans – high fever, headache, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, myalgia, uveitis, jaundice, rash; may resolve and then relapse with greater severity; kidney failure (nonoliguric, hyponatremia, hypokalemia), liver failure, pulmonary hemorrhages, meningitis, death Transmission: Bacteria is shed in infected animal’s urine and enters an uninfected animal through the the mucous membranes or skin wounds, often via contaminated water. Venereal transmission can occur in swine and cattle. Among dogs, hunting dogs, farm/herding dogs, and pet dogs that explore the outdoors are at greatest risk. Diagnosis: PCR or antibody level testing required for definitive diagnosis Treatment: Swine – Streptomycin injections, tetracycline feed additives Cattle – tetracycline, oxytetracycline, penicillin, ceftiofur, tilmicosin, tulathromycin Dogs – Doxycycline, supportive care (fluid therapy, antiemetics, GI protectants, phosphate binders, hepatic support diets and medications) Humans – Penicillin, doxycycline, supportive care Prevention: Vaccination is the best method of control in animals! Additional management practices help reduce risk – good facility sanitation and rodent control. Maintenance of pens to prevent injuries. Do not allow pigs contact with cattle, horses, dogs, or cats. Do not graze cattle with sheep. Do not allow pigs into the areas used to house other susceptible species. Avoid open drains and communal drinking troughs to limit spread between pens; limit mixing of pigs from different herds or pens as much as possible. Maintain closed herds, and do not share bulls or boars. Humans – No vaccine available. Use PPE whenever working around pigs (especially when handling urine, afterbirth, aborted fetuses, performing artificial insemination, or assisting with dystocias) or any individuals of other species suspected to have leptospirosis. Avoid drinking or wading/swimming in contaminated water. Sources: State of Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Merck Veterinary Manual, MSD Animal Health (image of dog), horsesidevetguide.com (horse image), NADIS (cattle images), leptospirosis.org (human image), CDC

#Leptospirosis#Lepto#Weill’s disease#recurrent uveitis#Leptospira spp#swine#dog#cattle#horse#sheep#pig#hog#wildlife#One Health#zoonoses#vaccination#equine#livestock#preventative medicine#veterinary#animal husbandry#diseases#biosecurity

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tulathromycin Market Size, Current & Upcoming Trends, Local Supply, Explain the Imminent Investment 2026

Global Marketers recently added its expanding repository with a new research study. The research report, entitled ”Tulathromycin Market” mainly includes a complete segmentation of this sector that is expected to generate massive returns by the end of the forecast period, showing a significant growth rate on an annual basis over the coming years. The research study also discusses the need for Tulathromycin Market explicitly.

Get Sample Report in PDF Version along with Graphs and Figures@

https://www.reportspedia.com/report/chemicals-and-materials/global-tulathromycin-market-report-2020-by-key-players,-types,-applications,-countries,-market-size,-forecast-to-2026-(based-on-2020-covid-19-worldwide-spread)/69838#request_sample

A detailed study of the competitive landscape of the Tulathromycin Industry Market has established, providing insights into the corporate profiles, latest developments, mergers, and acquisitions, and therefore the SWOT analysis. This breakdown report will offer a clear program to readers' concerns regarding the overall market situation to further choose on this market project.

Key players profiled in the Tulathromycin Market report includes:

AVF Chemical Industrial Hubei Honch Pharmaceutical Jiangsu Lingyun Pharmaceutical Livzon New North River Pharmaceutical Zhejiang Genebest Pharmaceutical Amicogen (China) Biopharm Hubei Widely Chemical Technology Zhejiang Guobang Pharmaceutical Zoetis

Ask For Discount:

https://www.reportspedia.com/discount_inquiry/discount/69838

Geographically, the Tulathromycin report includes the research on production, consumption, revenue, market share and growth rate, and forecast (2020-2026) of the following regions:

United States

Europe (Germany, UK, France, Italy, Spain, Russia, Poland)

China

Japan

India

Southeast Asia (Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam)

Central and South America (Brazil, Mexico, Colombia)

Middle East and Africa (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Egypt, South Africa, Nigeria)

Other Regions

Inquire Before Buying:

https://www.reportspedia.com/report/chemicals-and-materials/global-tulathromycin-market-report-2020-by-key-players,-types,-applications,-countries,-market-size,-forecast-to-2026-(based-on-2020-covid-19-worldwide-spread)/69838#inquiry_before_buying

The global Tulathromycin Market is expected to witness of massive growth in the next few years. The rising level of competition among the players and the increasing focus on the growth of new products are likely to offer promising growth during the forecast period. The research study on the global Tulathromycin Market deals with a complete overview, highlighting the key aspects that are projected to surge the growth of the market in the near future.

Tulathromycin Market Segmentation by Type:

>99.0% 98.0%≥ - ≤99.0% <98%

Tulathromycin Market Segmentation by Application:

Cattle Pig Others

What To Expect From The Report

A complete analysis of the Tulathromycin Market

Concrete and tangible alterations in market dynamics

A thorough study of dynamic segmentation of the Tulathromycin Market

A complete review of historical, current as well as potentially predictable growth forecasts concerning volume and value

A holistic review of the dynamic market modifications and developments

Remarkable growth-friendly activities of leading players

Some Major TOC Points:

Chapter 1. Tulathromycin Market Report Overview

Chapter 2. Global Tulathromycin Growth Trends

Chapter 3. Tulathromycin Market Share by Key Players

Chapter 4. Breakdown Data by Type and Application

Chapter 5. Tulathromycin Market by End Users/Application

Chapter 6. COVID-19 Outbreak: Tulathromycin Industry Impact

Chapter 7. Opportunity Breakdown in Covid-19 Crisis

Chapter 9. Tulathromycin Market Driving Force

And Many More…

Get Full Table Of Contents:

https://www.reportspedia.com/report/chemicals-and-materials/global-tulathromycin-market-report-2020-by-key-players,-types,-applications,-countries,-market-size,-forecast-to-2026-(based-on-2020-covid-19-worldwide-spread)/69838#table_of_contents

Conclusively, this report is a one-stop reference point for the industrial stakeholders to get the Free Tulathromycin Market to forecast of till 2026. This report helps to know the predictable market size, market status, future development, growth opportunity, challenges, and growth drivers by analysing the historical overall data of the considered market segments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mycoplasma Bovis; A Neglected Pathogen in Nigeria- A Mini Review-Juniper Publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF DAIRY & VETERINARY SCIENCES

Abstract

Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis) is the second most pathogenic bovine mycoplasmas known worldwide. It is associated with various diseases in cattle including calf pneumonia, mastitis, arthritis, otitis media, kerato conjunctivitis and genital disorders. Few antimicrobials like tulathromycin, florfenicol, fluoroquinolones and gamithromycin are currently approved for treatment of M. bovis infection worldwide. Antibiotic treatment must be instituted early in the course of the disease, and pain relief should be provided for sick cows and calves. Vaccines have been reported to be available against the infection, but have not been proved protective. Early detection of disease, improved husbandry conditions and treatment with effective antimicrobial are currently the best approach in the control of the disease. Mycoplasma bovis infection being a most important emerging disease of cattle is new and poorly understood among cattle owners and field veterinarians in Nigeria. Research to establish the molecular basis and distribution of the disease in Nigeria is recommended.

Keywords: Cattle; Disease; Mycoplasma bovis; Nigeria

Introduction

Mycoplasma bovis is the second most pathogenic mycoplasma after Mycoplasma mycoides subspecies mycoides the causative agent of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia [1]. It was first definitively identified in the USA in 1961 from a cow with mastitis, although clinical signs associated with the organism were described beforehand [2]. It is now recognized as a worldwide pathogen of intensively farmed cattle and in recent years has emerged as an important cause of infection in young dairy calves in North America and Europe [3]. A member of the wall-less bacterium belongs to the Class Mollicutes, Order Mycoplasmatales, Family Mycoplasmataceae, and the Genus Mycoplasma [4] and is among the smallest and simplest free- living micro-organisms capable of self-replication [5].

The organism causes bovine mycoplasmosis, an infection that leads to a variety of clinical manifestations mostly of chronic nature, including bronchopneumonia [2], otitis media [6], mastitis [7], genital disorders [8], arthritis [9], meningitis [10] and kerato conjunctivitis [11]. Mycoplasma bovis can affect a large variety of tissues and organs and can also be isolated from apparently healthy cattle [12]. Several reports have suggested that mycoplasmas are frequently present in the cattle population, causing disease in conditions of impaired immune response due to stress of transportation, adverse weather condition and impaired feeding [13,14]. It adversely affects growth rates resulting in increased cost of production and additional treatment cost, resulting in large economic losses to the cattle industry [15]. The organism is considered to be one of the major emerging pathogens of cattle in industrialized countries threatening livestock production [16]. Elimination of M. bovis is difficult and treatment with antimicrobials is unsuccessful unless animals are treated early in the course of disease [17]. There are no vaccines available commercially against M. bovis infection, although the use of auto genus vaccines has shown some success [18]. It is important to effectively target antimicrobial treatment to ensure prudent use of antimicrobials and to reduce the development of antimicrobial resistance [17].

Currently few reports are available on M. bovis infection in Nigeria despite the prevalent nature of the organism as reported by these authors [19-23]. On this background, this overview of the infection was presented. The following aspects are discussed:

a) Epidemiology,

b) Clinical signs,

c) Diagnosis,

d) Treatment,?

e) Control and

f) Information about the infection in Nigeria.

4. Epidemiology

Mycoplasma bovis is well adapted to colonization of mucosal surfaces, where it can persist without causing clinical disease. The upper respiratory tract (URT) mucosa is the primary site of M. bovis colonization in cattle following URT exposure [24]. After intra mammary exposure, the mammary gland appears to be the major site of colonization [25]. Irrespective of the route of exposure, M. bovis can be isolated from numerous body sites during early infection, particularly the URT, mammary gland, conjunctiva and urogenital tract [26]. Mycoplasmemia during M. bovis infection has earlier been documented [24,2 5]. The URT mucosa and the mammary gland appear to be the most important sites of persistence and shedding of the organism [26]. Although many cattle shed M. bovis for a few months or less, some cattle can shed the organism sporadically for many months or years [26,27]. The factors responsible for sporadic shedding have not been determined. However, it has been reported that cattle with clinical disease usually shed large numbers of M. bovis [1]. Stressful conditions such as transportation, comingling, entry into a feedlot, and cold stress are associated with increased rates of nasal shedding of M. bovis [15]. Chronic asymptomatic infection with intermittent shedding of M. bovis appears critical to the epidemiology of infection, especially the maintenance of the agent within a herd and exposure of naive populations [1].

Clinical Signs

Mycoplasma bovis infection is multi factorial and can manifests itself in any/or combination of the following clinical signs.

Pneumonia

Mycoplasma bovis-associated pneumonia can be manifested in any cattle in a herd/or farm irrespective of age [2]. Clinical signs are imprecise and include fever, hyperpnoea, dyspnoea, and decreased appetite, with or without nasal discharge and coughing [2]. The severity of calf pneumonia can be further compounded by animal husbandry, the environment, low effectiveness of many antimicrobials, and unknown efficacy of vaccines [18,28]. Mycoplasma pneumonia can be accompanied by cases of otitis media, arthritis, or both, in the same animal or in other animals in the farm/herd. Chronic pneumonia and polyarthritis syndrome (CPPS) occur when animals develop polyarthritis in association with chronic pneumonia, and do occur in beef cattle after some weeks of entry into feedlot [1].

Mastitis

The herd presentation of mycoplasma mastitis varies from endemic subclinical disease to severe clinical mastitis outbreak [29]. Many infections are subclinical, and few numbers of sub clinically infected cows have a marked decrease in somatic cell count or reduced milk production. Cows of any age or stage of lactation are affected [25]. When the disease is clinical, signs are nonspecific and typically more than one quarter is affected. There is a drastic decline in milk production and signs of systemic illness are relatively mild [29]. The mammary gland might be distended but is not usually painful. Secretions vary from mildly abnormal to gritty or purulent, and are sometimes brownish in color. A history of mastitis that is resistant to treatment with antimicrobials is common, and clinical disease can persist for several weeks [1,29]. Arthritis, synovitis, joint effusion or respiratory disease in mastitic or nonmastitic cows can accompany M. bovis mastitis [1,30].

Otitis media

Mycoplasma bovis-associated otitis media occurs in dairy and beef calves as enzootic disease or as outbreaks, and also occurs sporadically in feedlot cattle. In early or mild cases calves remain attentive with a good appetite, but as disease progresses they become febrile and anoraexic. Clinical signs occur as a result of ear pain and facial nerve deficits, especially ear droop and ptosis [31,32]. Ear pain is evidenced by head shaking and scratching or rubbing ears. Epiphora and exposure keratitis can develop secondary to eyelid paresis. Clinical signs can be unilateral or bilateral, and purulent aural discharge can be present if the tympanic membrane has ruptured [1]. Concurrent cases of pneumonia, arthritis, or both are common. Otitis interna and vestibulocochlear nerve deficits can occur as result. Head tilt is the most common clinical sign, but severely affected animals can exhibit nystagmus, circling, falling, or drifting toward the side of the lesion and vestibular ataxia [33]. In advanced otitis media-interna, meningitis can develop. Spontaneous regurgitation, loss of pharyngeal tone, and dysphagia has also been reported and are indicative of glossopharyngeal nerve dysfunction with or without vagal nerve dysfunction [1].

Arthritis, synovitis and periarticular infection

Mycoplasma bovis-induced arthritis is supposed to be a consequence of mycoplasmemia [1]. Arthritis was preceded by mycoplasmemia in one calf that was inoculated intratracheally with M. bovis [25]. Infections of other body systems that occasionally accompany polyarthritis are also likely to be a consequence of mycoplasmemia [34]. Clinical cases of M. bovis- induced arthritis in dairy calves tend to be sporadic and are typically accompanied by respiratory disease within the herd and often within the same animal [34]. Clinical signs are typical of septic arthritis with affected joints being painful and swollen, and calves display varying degrees of lameness and may be febrile in the acute stage of infection [35]. Cattle of any age can be affected by M. bovis arthritis [30]. Chronic Pneumonia and Polyarthritis Syndrome (CPPS) have been described in feedlot cattle [9]. Clinical signs are typical of septic arthritis, including acute non-weight bearing lameness with joint swelling, pain, and heat on palpation. The animal might be febrile and anorectic. Involvement of tendon sheaths and periarticular soft tissues is common. Large rotator joints (hip, stifle, hock, shoulder, elbow, and carpal) are commonly affected, although other joints such as the fetlock or even the atlantooccipital joint can be involved. Poor response to treatment is a common feature [30].

Kerato conjunctivitis

Mycoplasma bovis can be isolated from the conjunctiva of healthy and diseased cattle [11,25], although M. bovis-associated ocular disease is considered uncommon [36]. However, there are several reports of outbreaks of kerato conjunctivitis involving M. bovis alone, or in mixed infections with Mycoplasma bovoculi [11,37]. An outbreak of severe kerato conjunctivitis, from which M. bovis was the only consistently isolated pathogen, was reported in a group of 20 calves. Clinical signs included mucopurulent ocular discharge, severe eyelid and conjunctival swelling, and corneal oedema and ulceration which can resolve within 2 weeks [38]. In a report by Alberti etal., [11], an outbreak of M. bovis-associated kerato conjunctivitis in beef calves in Italy was followed by cases of pneumonia and arthritis.

Meningitis

Mycoplasma bovis infection can cause meningitis in calves which can sometimes be difficult to identify, as calves may just appear to have fevers and be depressed. Signs of apparent neck pain and abnormal eye movements may also be evident [39]. Meningitis can also occur as a complication of mycoplasma otitis media-interna. Mycoplasma bovis has also been isolated from the cerebral ventricles of young calves with clinical signs of meningitis in conjunction with severe arthritis, suggesting disseminated septic disease [1].

Genital Disorders

In isolated and predominantly experimental cases, Mycoplasma bovis has been associated with genital infections such as abortion in cows and seminal vesiculitis in bulls. However, there is little facts to support an important role for M. bovis in naturally occurring bovine reproductive disease [1].

Diagnosis

Rapid and accurate diagnosis of M. bovis infections is compromised by the low sensitivity and, in some cases, specificity of the available tests, and subclinical infections and intermittent shedding complicate diagnosis [1]. Various laboratory tests are currently used for the screening, detection and confirmation of the pathogen in cattle. Detection of the M. bovis organism is generally carried out either by a capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), or culture isolation using special media, or molecular tests [15]. Serological methods are useful screening tests but of limited use at the early stage of infection as sero-conversion is usually at least two weeks post infection. The isolation and culture of Mycoplasma species requires specialist skills and is not always successful due to multiple mycoplasma infections, or presence of other bacteria [39,5]. It has been previously reported that the specificity of serological, culture and some molecular tests may have limitations, and may result in misidentification or inconclusive results [40,41].

Treatment

The good news about Mycoplasma bovis infection is that unlike other mycoplasma diseases, antimicrobials are recommended for its treatment. Although there is scanty information about pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data on the treatment of M. bovis infections [1]. There is no effective therapy of mastitis and only limited success in treatment of respiratory and joint infections caused by M. bovis have been reported [2,42]. Two antimicrobials have been approved in the United States for treatment of bovine respiratory disease (BRD) associated with M. bovis. These are tulathromycin (Draxxin, Pfizer Animal Health, New York, NY) and florfenicol (Nuflor Gold, Intervet/Schering-Plough Animal Health, Summit, NJ). Another macrolide, gamithromycin (Zactran Injectable Solution, Merial Canada, Baie d'Urfe, Quebec, Canada), is approved for treatment of M. bovis-associated BRD in Canada [1]. However, in countries where fluoroquinolones and spectinomycin do carry appropriate labels, they have been recommended to be the most effective drugs for treatment of M. bovis infections [1,43]. Antibiotic treatment must be done early in the course of the disease, and pain relief should be provided for sick cows and calves [44].

For the treatment of M. bovis-associated arthritis have an especially poor response to treatment. Aggressive early treatment before the development of extensive tissue necrosis seems most likely to be successful. Fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and macrolides tend to have good distribution into joints [45]. Myringotomy with irrigation of the middle ear has been recommended for the treatment of otitis media in calves. There is a report of successful surgical treatment of a calf with M. bovis-associated otitis media-interna in which a bilateral tympanic bulla osteotomy was performed [33].

Prevention and control

Although vaccines have been reported to be available in developed nations against this infections, but have not proved to be protective [14,46]. The best way to prevent Mycoplasma bovis infections is probably to maintain a closed herd or, if that is not possible, to screen and quarantine newly purchased animals. The use of sick boxes for sick cows and good sectioning of different age groups of calves and young animals are very important to prevent outbreaks [44]. Calf health records should be examined where necessary to determine if M. bovis-associated diseases such as otitis media have been observed. [1]. Early detection of disease, improved husbandry conditions, and treatment with effective antimicrobial are currently the best approach in the control of the disease [15].

Information about the infection in Nigeria

Nigeria being a giant of Africa is endowed with abundant livestock resources with estimated cattle population of19.5 million which make the country number one in livestock production in Africa [47]. The country could not utilize up to 50% of its dairy and beef industries as compared to developed nations. Diseases are regarded as setbacks in actualization of animal production in Nigeria of which Mycoplasma bovis infection is among [48]. This organism has been documented to cause economic impacts in those countries that are certified free from contagious bovine pleura pneumonia [49]. To the best of my knowledge, there are as such few reports available on Mycoplasma bovis infection in Nigeria. Mycoplasma bovis infection being one of the serious economic diseases of cattle has not been given sufficient attention it deserves [50]. Epidemiological studies were conducted in northwestern states of Nigeria [20,21] and northeastern Nigeria [22,23,48], the authors reported M. bovis to be prevalent in their study areas. Ajuwape et al. [20] reported 23.1% prevalence using biochemical and serological identification on pneumonic lung tissues of cattle; Tambuwal et al. [21] reported 66% servo prevalence using sera samples of cattle; Egwu et al. [19] reported 1.5% prevalence using isolation and biochemical identification of apparently normal and pneumonic lungs of sheep and goats. Whereas Francis et al. [49] and Francis et al. [23] reported 2.0% and 19.5% respectively using pneumonic lungs and sera samples of cattle.

There are reports of high number of cases of ear infections, arthritis and coughing being encountered on the field/farm more especially in the northern Nigeria which points at M. bovis infection, but in most instances such cases are ignored or misdiagnosed (Francis, personal observation). To the practicing veterinarian in the field, once face with such cases, his mind will be directed towards Contagious Bovine Pleuropeumonia (CBPP) which in also presents similar clinical signs and thereby neglecting other causative agents such as M. bovis infection.

Conclusion

Mycoplasma bovis infection could be a most important emerging disease of cattle and small ruminants has been reported to be a reservoir of the infection in Nigeria. But because the disease seems to be new and poorly understood among cattle owners and field veterinarians, researc

h is therefore needed to establish the molecular basis and distribution of the disease in Nigeria. As at present, a research work is in progress in northeast Nigeria, which aimed to identify and confirm whether pathologic lung lesions encountered in most abattoirs in the region were as a result of CBPP or co-infection with other pathogenic mycoplasmas which M. bovis is one of the targets.

For more Open Access Journals in Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/open-access.php

For more articles in

Open Access Journal of Dairy & Veterinary sciences

please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jdvs/index.php

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes