#Total Gamma Radiation Reported – USA Week 10

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

up the atom without a science degree: Goiânia

(The majority of this post was originally written in 2015 on my personal blog. Any research errors are entirely mine. Images are taken from the IAEA report on the incident.)

So yeah, I said I’d talk about Goiânia. This is one of the most, if not the most, astonishingly awful radiological accidents involving an orphaned source in the history of ever, and it is a really good illustration of why orphaned sources are amazingly dangerous.

If you lose track of a radioactive source through oversight or general incompetence or whatever sort of fuckup, you no longer have control over where that source goes and who gets to play with it under what conditions. Anyone can come along and pick it up and take it home with them and subsequently need to have parts of themselves amputated – or just straight-up die in extremely unpleasant ways. Because the radiation given off by source capsules is invisible, impossible to smell or taste, people have no way of knowing that anything is even happening until the vomiting starts.

There are two main types of orphaned-source accident: the industrial-radiography source and the radiotherapy source. (You also see this with the sources inside forgotten radioisotope thermal generators scattered around the former Soviet Union.) With the radiotherapy source accidents, what happens is that some dingleberry fails to correctly decommission an external-beam radiotherapy machine and secure its source capsule, and the machine or parts of it subsequently falls into the hands of enterprising scrap dealers who take it apart. This is what happened in Goiânia, in Mexico, in Thailand, in Istanbul, and God knows how many other places over the past sixty-something years.

Radiotherapy can take many forms: teletherapy (now known as external beam radiotherapy), where the source of radiation is outside but focused on the body; brachytherapy, where sealed radioactive sources are placed inside or next to the part of the body needing treatment; and systemic or unsealed source radiotherapy, where a soluble radionuclide is injected or ingested into the body. Mostly when people think of radiotherapy they think of external-beam machines with the rotating gantry and patient couch.

These days EBRT is mostly performed using linear accelerators, which produce a powerful beam of either electrons or X-rays with the push of a button and do not require dangerous radioactive source capsules, but in the early days of teletherapy you had your gamma emitters and you damn well liked it. The two most common radioactive isotopes used in teletherapy sources are cobalt-60 and caesium-137, contained in sealed steel source capsules that sit inside heavy lead shielding when not in use. The caesium-137 source in the Goiânia accident was filled with highly soluble, highly dispersible caesium chloride powder. If it had been a cobalt source, it would probably have been full of lots of little individual pellets, like the one involved in the Juarez orphaned-source accident in 1983. The fact that the caesium was in the form of a crumbly powder that could be daubed onto the skin, like carnival glitter, would turn out to be important.

The unit involved in the accident was a Cesapan F-3000, a 1950s Italian design containing a source capsule thought to have been manufactured at Oak Ridge in the seventies.

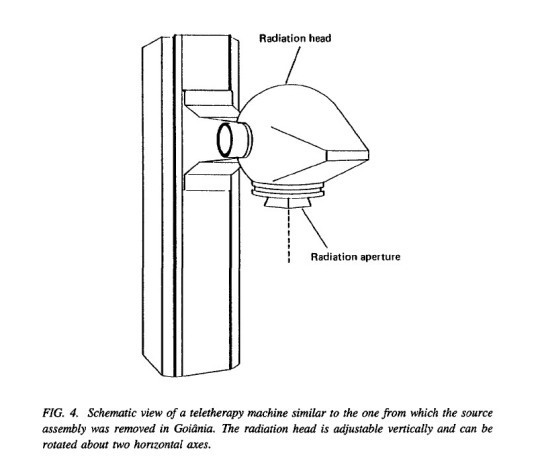

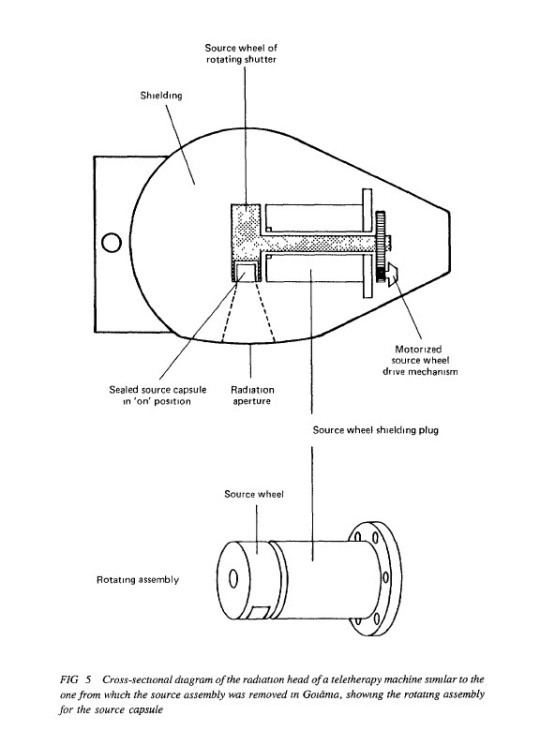

It would have looked a little something like this (images from IAEA report).

The rather ominous-looking head was capable of moving up and down on its support pillar and rotating round a horizontal axis, and contained the stainless-steel source capsule in a rotating assembly that could move to line up the window in the capsule with the radiation aperture in the head, as illustrated here.

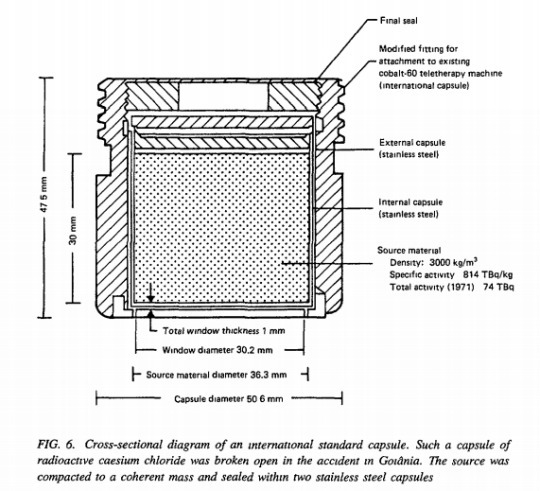

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) report, the source capsule itself was of standard international dimensions and potency. It was tiny. It was less than two inches tall and just about two inches in diameter. You know those adorable little one-ounce mini jam jars? It was about that size. It killed four people and forever altered the lives of a whole bunch of others, required seven houses to be demolished (and the bits disposed of as radioactive waste), and cost millions and millions of dollars in damage.

Some accounts of this mess state that the source capsule’s 1mm-thick “window” was made of iridium, but on further research I have not been able to track down any supporting documentation for this claim: it was most likely just a thinner bit of the stainless-steel capsule itself without the shielding that covered the rest of the source. Definitely not made of glass: you would not have been able to see the source material through any such window, no matter what Reddit creepypasta authors would like you to believe.

The source capsule, as illustrated by IAEA.

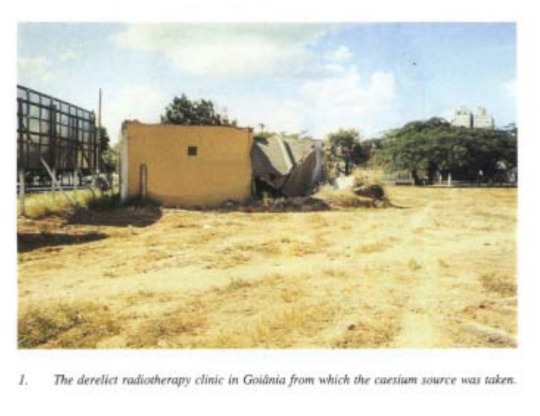

This machine was left in the derelict premises of a private radiotherapy clinic in Goiânia, capital of Goiâs State, Brazil, after the partnership that owned it dissolved toward the end of 1985; a cobalt teletherapy unit from the same clinic premises was removed and transferred to a new facility, but the caesium unit stayed where it was, presumably because nobody was sure who was actually responsible for dealing with it, or notifying the authorities that any of this had happened. At the time of the IAEA report nothing was 100% clear and legal action was being pursued, so they covered their collective ass and left this part of the narrative somewhat vague.

Most of the building was knocked down, but the treatment rooms were left derelict and totally unsecured. Vagrants used the gutted building to shelter in; wildlife came and went, and the Cesapan F-3000 stood there hiding its deadly little heart in plain sight. I’m honestly a bit surprised that it took as long as it did before somebody considered its potential scrap value.

On September 10, 1987, two men, A and B, began to try to dismantle the machine. It took a while and several attempts, but by September 13 they’d managed to extract the rotating source assembly from the massive shielding of the radiation head. Outside this shielding, the unprotected source in its assembly was giving off 465 rads an hour, or 4.65 gray if you want to be modern about it. For comparison, the accepted annual radiation dose for non-nuclear-workers in the USA is between 1 and 5 millisieverts, or ~ 0.001 to 0.005 gray.

They put the assembly in a wheelbarrow and took it to A’s house, as A had suggested salvaging the machine for scrap in the first place. Both of them were feeling sick and had started to vomit by the end of the day, but they figured hey, it must’ve been something they ate.

Next day, B was feeling dizzy and having diarrhea as well as vomiting. One of his hands was swollen, and he would subsequently develop a burn on his hand and wrist corresponding to the size and shape of the beam aperture in the rotating assembly. He had been holding it with that hand over the aperture. The next day, September 15, he went to the doctor – and was told that his symptoms were due to a food allergy and he was to take it easy for a week.

Over the days between September 13 and September 18, A had been tinkering with the rotating source assembly, which he’d dumped under a mango tree in his yard. He was trying to get the source capsule free of the assembly. At some point he managed to poke a hole through the thin steel window of the source with a screwdriver.

He thought that perhaps the intensely radioactive caesium chloride thus exposed might be gunpowder, and tried to light it.

On the 18th he managed to get the broken-open source free of the rotating assembly, and sold the whole mess to a third man, C, who owned a junkyard nearby. That night, C went into the garage where the bits were stored and noticed that the stuff in the opened capsule was emitting* a blue glow, and brought the capsule into his house to show it to his wife. Because it was so pretty and so strange, they thought it might be valuable, or have supernatural powers, and invited their friends over to have a look. On the 21st one of these friends dug out some of the powder with a screwdriver and took it away with him to give to his family and friends. Quite a few of them rubbed it on their skin like body glitter. C received a total dose of 7Gy and survived. His wife (5.7 Gy) would not.

I know this reads like a horror novel. It gets worse.

More people were (unsurprisingly) suffering the symptoms of acute radiation sickness: C’s vomiting wife was examined at a local hospital, diagnosed with food poisoning, and sent home to rest. Her mother came over to take care of her, and took home a dose of 4.3 Gy.

Two of C’s employees were tasked with removing lead from the remnants of the assembly, and worked on it from September 22 to 24. Directly exposed to the breached source capsule, they would be among the four victims who did not survive.

The last of the four fatalities was C’s six-year-old niece, whose father had visited C and taken away some of the glowing powder. This was left on the table and handled by the family during meals. The little girl had played with the powder, rubbed it on her skin, and then eaten a sandwich with glowing dust still clinging to her hands. According to one source, when international medical teams arrived to treat the victims, they found her in an isolated room in the hospital because she was so contaminated the staff were afraid to go near her.

On the 23rd, B was admitted to hospital: his skin lesions were diagnosed as related to some exotic disease, and on the 27th he was transferred to the Tropical Diseases Hospital.

After doing its damage to C’s friends and family, the remains of the source and rotating assembly were sold to a second junkyard. The sudden epidemic of vomiting and diarrhea among their acquaintances was not lost on C’s wife, who became convinced that the glowing powder from the capsule was responsible for all the sickness. On the 28th, ten days after the source was transferred to C’s ownership, she and one of C’s employees went to collect the remains of the source and rotating assembly from the second junkyard, put it in a plastic bag, and took it by bus to the local Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (Health Surveillance Agency, similar to the American FDA) office, spreading contamination as they went. At the Vigilância Sanitária, the employee and C’s wife presented a doctor, P, with the source in its bag, and she told him that it was “killing her family.”

By now the employee who had carried the bag was developing a skin lesion on his shoulder, where it had rested, and he and C’s wife were sent to the Tropical Diseases Hospital, where B and several other contamination victims had also been sent for treatment. One of the doctors at the TDH was beginning to suspect that in fact the nearly identical symptoms of this whole cohort of patients could have been caused by radiation, and he contacted a TDH colleague who also served as the superintendent of the Toxicology Information Center. It turned out that this colleague had also been contacted by Dr. P from the Vigilância Sanitária regarding the “killer” bag C’s wife had brought to him. Dr. P had initially thought that the bag contained bits from X-ray apparatus, and became wary of it, moving it outside the facility (and thus probably saving his own life).

The doctors at the TDH had another look at the patients, with the mysterious bag’s contents in mind, and agreed that it would be a good idea to contact the state department of the environment; when they did, it was recommended that a medical physicist examine the package.

On the 29th they found a medical physicist, W. That morning, he borrowed a radiation monitor used for uranium prospecting, which had a range of 0.03–30 microgray/hour, and set off for the facility to which C’s wife had brought the source: quite some distance away he noticed that the monitor was pegged no matter where he pointed it. He assumed it was malfunctioning and went back to fetch a different one, which showed exactly the same thing as soon as he turned it on.

At this point W realized that something was desperately wrong. At the Vigilância Sanitária, Dr. P had become sufficiently concerned about the source in its bag that he had called the fire department, which had arrived and was preparing to chuck the whole thing into a handy river. W arrived on the scene mid-morning, just in time to prevent this. He convinced them to evacuate the building and make sure no one else got near it, and after talking with Dr. P they set off together to C’s junkyard–where the monitor again read off the scale. It was now midday.

W, among others, managed after some effort to notify the secretary of health, which took up much of the afternoon. Once the authorities had been convinced that yes, in fact, this was a huge deal and would require evacuation of a large number of people, steps began to be taken with considerably greater speed. The physicist and physician at the radiotherapy clinic’s new location were notified, and the source was tentatively traced to the abandoned clinic and the caesium unit.

Throughout the evening and into the night, the scope of the emergency became clearer. Civil defense forces were notified; the TDH was informed that a number of patients were contaminated; the known sites of contamination were resurveyed with equipment from the radiotherapy clinic; an emergency receiving and decontamination facility was set up in a local stadium. W, the physicist who had initially discovered the contamination, was contacted by an individual who had intended to cut up the source for C with an oxyacetylene torch (but had luckily forgotten to do so), who explained several useful details to the investigation including the locations where the source assembly had been broken up and where the parts had been taken.

The remains of the source capsule, still sitting in the courtyard of the Vigilância Sanitária where Dr. P had put them, were still putting out astonishing amounts of radiation, and the nuclear emergency coordinator who had arrived from Rio de Janeiro around midnight arranged for a crane to hoist a section of sewer pipe over the wall of the courtyard and lower it down over the chair on which the bag of source bits lay. The section of pipe surrounding the chair was then filled with concrete pumped over the wall, entombing the source and cutting down the amount of radiation it was emitting.

That’s one way to do it.

~

International teams were sent in to decontaminate and treat the victims of the disaster. There isn’t a hell of a lot you can do about radiation sickness: you can’t undo the damage, all you can hope to do is try and manage the acute effects and do everything you can to prevent infection. In this case, therapy consisted of managing the acute-radiation-syndrome hematological crisis and subsequent immune deficiency, treating the burns, removing contamination from the body (decorporation), and general support.

I think Goiânia still represents the worst caesium-137 contamination accident of all time. External decontamination was relatively simple to achieve, but a lot of the patients recontaminated their skin repeatedly by sweating; the caesium in their bodies found its way out in everything. Chelation with Prussian blue helped a significant number of the victims, a point which recalls the hopeless suggestion of treating Louis Slotin with methylene blue after his deadly exposure to plutonium criticality.

The final count of people with significant contamination, out of the many screened, was two hundred and forty-four. Most of those were lucky and received fractionated doses–spread over a long time period, giving the body’s tissues a chance to attempt to recover from the damage. Some were not. The dead of Goiânia–two men, one woman, and one six-year-old girl–had to be buried in lead coffins surrounded by concrete.

Caesium didn’t just destroy people in Goiânia, it destroyed property and livelihoods. Seven houses had to be demolished, so badly contaminated they could not be made safe. Topsoil was removed by the ton. In total 85 houses had to be decontaminated.

Of the orphaned-source accidents known to the internet, Goiânia is probably the most horrific because of the tragic fascination the source inspired in those who saw it and had no idea of its actual nature. It shares some aspects with the Radium Girls tragedy–they didn’t just ingest the stuff when they pointed their dial-painting brush-tips with their mouths, they painted themselves with it. Who wouldn’t want to be the only girl in the nightclub with eerily beautiful glowing fingernails or teeth? In Goiânia, the glittering, glowing blue substance was just as irresistible. One man took a piece of it to set in a ring for his wife. Others, as previously mentioned, rubbed it on their skin like body glitter.

IAEA: It is relevant to note that the interest aroused by the blue glow that emanated from the radioactive caesium chloride significantly affected the course of the accident. Also, caesium chloride’s high solubility contributed to the extensive contamination of persons, property and the environment. But for these factors, the accident might have developed similarly to the accident with cobalt-60 that occurred in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, in 1983, which resulted in little contamination and no deaths.

But the real lesson to learn here is do not fucking leave radioactive sources lying around. Of course it wasn’t learned; there have been a bunch more predictably tragic orphaned-source accidents since Goiânia. Like the industrial irradiator accidents, they all have basically the same plot, with varying levels of awfulness; and like the industrial irradiator accidents, I don’t really see how they can be completely prevented in the future, except by increased attention to correct record-keeping and proper custody of dangerous materials, and people are always going to be fallible and fuck things up. It’s a cautionary tale.

*This blue glow is somewhat mysterious. Here’s what the IAEA said about it in 1988: Subsequently, the phenomenon of the blue glow was observed by individuals from ORNL and the United States Department of Energy’s Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site (REAC/TS) at Oak Ridge, USA, during the disencapsulation of a caesium-137 chloride source in early 1988. This glow is thought to be associated with fluorescence or Cerenkov radiation due to the absorption of moisture by the source. Further study is in progress in Oak Ridge to determine the nature of this blue glow.

#up the atom without a science degree#the goiania incident#orphaned source#images taken from IAEA report#research is for fun#research is for writing#not book related

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

HELLO WORLD! DREADED RADIOACTIVE POLLEN, DEAD CHERNOBYL RADIOACTIVE TREES THAT DON'T ROT, SAD AND PATHETIC COVER STORY OF "GLOBAL WARMING" AND THE MILLION A WEEK CLUB - WEEK 10 - YOUR RAD THIS WEEK

HELLO WORLD! DREADED RADIOACTIVE POLLEN, DEAD CHERNOBYL RADIOACTIVE TREES THAT DON’T ROT, SAD AND PATHETIC COVER STORY OF “GLOBAL WARMING” AND THE MILLION A WEEK CLUB – WEEK 10 – YOUR RAD THIS WEEK

Facing a Dying Nation MILLION A WEEK CLUB – Your Rad this Week – Week 10 By Bob Nichols March 24, 2018 Are you in a city that gets a Million Counts of Radiation a Week? First, how on earth are you going to find out? Folks, that is a secret, isn’t it? This is a Bad situation for all exposed to the Rad. Now included, for the 10th Week of 2018 just passed, all cities above 10,000,000 CPM Year to…

View On WordPress

#DodgeTheRads#30 Cities above 10 Million CPM in Week 10 of 2018#Japan#MILLION RAD COUNT CITIES#Nuclear#Radioactive Isotopes#SPOTLIGHT on Rad in Colorado Springs#Target Population#TOTAL GAMMA RAD in the USA#TOTAL GAMMA RADIATION recorded in the US – 2017 Final Rad Count#Total Gamma Radiation Reported – USA Week 10#USA#we are the media now

0 notes