#Thursday Ghana Fortune

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fortune Thursday Live Free Lotto Banker For 07/09/2023

Fortune Thursday Live Free Lotto Banker For 07/09/2023 Fortune Thursday live free lotto banker – Live Banker Today fortune lotto 2sure is going to be live sure banker that will not fail us and i want you to play it with our number. 2sure fortune live banker – Get thursday Lotto Banker and 2sure + 3Direct Strong One Live now with 2 BANKER To Carry directly, 2sure fortune live banker for this week…

View On WordPress

#Banker For Today fortune lotto#best lotto banker for today#Fortune 2 live banker for today lotto#fortune 2sure#fortune best numbers to play today#fortune Confirmed Two Sure#Fortune ghana live banker#Fortune Ghana lotto forecast for today#Fortune ghana lotto live#Fortune Live Banker#fortune lottery authority ghana#Fortune Lottery in Nigeria#Fortune Lotto Banker#Fortune lotto free banker#Fortune Lotto Key Position Banker#fortune lotto two sure today#Fortune Prediction Today#Fortune Thursday live free lotto banker#free lotto banker#Ghana Fortune Lotto 2-Sure#Ghana fortune lotto 2sure key#Ghana Fortune Lotto 3direct#ghana fortune lotto banker#ghana Fortune lotto forecast#Ghana Fortune Lotto Forecaster#Ghana Fortune Lotto Long Perm#Ghana Fortune Lotto Perm7#Ghana Fortune Weekly Lotto#Ghana Lotto Prediction for Fortune#live Ghana Fortune banker

0 notes

Text

Bawumia promises reforms to turn Ghana’s fortunes around

Dr Mahamudu Bawumia, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) Presidential Candidate for the 2024 elections, Thursday expressed a strong conviction to turn the country’s fortunes around. “I trust in God to select a leader for the country…I also know that God can use me to change some situations,” he said during a meeting with Christian leaders in the Western Region as part of his two-day campaign…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Fortune Thursday Lotto Results & Machine (1st December 2022) – NLA

Fortune Thursday Lotto Results & Machine (1st December 2022) – NLA

Fortune Thursday Lotto Results and Machine (1st December 2022 /01/12/2022 ) – NLA Ghana. Check Thursday Lotto Result for Today 1st Dec. 2022, and Thursday Results for Tonight. Fortune Thursday Lotto Results 1st December 2022 We bring you the 1st December 2022 Thursday Lotto results, NLA Thursday results, and Thursday winning Numbers 1/12/2022. Fortune Thursday Lotto Results (1st December 2022…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

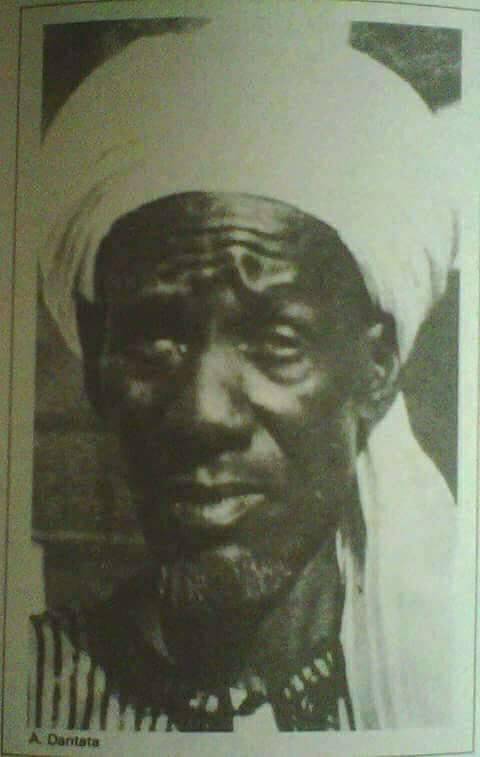

THE UNFORGETTABLE NIGERIAN: WEALTH, WEALTH EVERYWHERE

Alhaji Alhassan Dantata (1877 - August 17, 1955) was a Nigerian businessman who was the wealthiest man in West Africa at the time of his death.

HERITAGE

Dantata's father was Abdullahi, a man from the village of Danshayi, near Kano. Dantata was born in Bebeji in 1877, one of several children of Abdullahi and his wife, both of whom were traders and caravan leaders.

Bebeji was on the Kano to Gonja (now in northern Ghana) and Kano to Lagos routes. The people of Bebeji, at least those from the Zango (campsite) were great traders. Bebeji was considered a miniature Kano. There was a saying which went “If Kano has 10 kolas, Bebeji has 20 halves" or in Hausa: "Birni tana da goro goma, ke Bebeji kina da bari 20".

The town attracted many people of different backgrounds in the 19th century, such as the Yorubas, Nupes, Agalawas, etc. It was controlled by the Sarki (chief) of Bebeji who was responsible for the protection of Kano from attack from the southwest.

Alhassan was born into an Agalawa trading family. His father Madugu Abdullahi was a wealthy trader and caravan leader while his mother was also a trader of importance in her own right enjoying the title of Maduga-Amarya. Abdullahi, in his turn, was a son of another prosperous merchant, Baba Talatin. It was he who brought the family from Katsina, probably at the beginning of the nineteenth century, following the death of his father, Ali.

Abdullahi already had a reputation of some wealth from his ventures with his father and therefore inherited his father’s position as a recognized and respected Madugu. Like his father, he preferred the Nupe and Gonja routes. He specialized in the exchange of Kano dyed cloth, cattle, slaves and so on for the kola of the Akan forest. Surprisingly, he had added cowries brought to the coast by European traders to the items he carried back to Kano.

BIRTH AND EARLY LIFE

Abdullahi continued to operate from Madobi until 1877 when having just set out for a journey to Gonja, his wife delivered in the Zango (campsite) of Bebeji. The child was a boy and after the usual seven days, he was named Alhassan. Abdullahi purchased a house in the town and left his nursing wife and child to await his return from Gonja. On his return, he decided to abandon Madobi and moved to Bebeji. Some say that the house that contains his tomb is still held by the family. The date of his death is unknown, but it was probably about 1885 when Alhassan was between seven and eight years of age. By then he had brothers and sisters – Shuaibu, Malam Jaji, Malam Bala, Malam Sidi and others.

The children were too young to succeed to their father’s position and to manage his considerable wealth. They all received their portion according to Islamic law. Maduga Amarya was known to be such a forceful character that nobody in the Zango would take her to wife. She therefore decided to leave the children in Bebeji, in the care of an old slave woman, while she moved to Accra where she became one of the wealthier Hausa traders.

The slave was known as "Tata" from which circumstance young Alhassan became known as Alhassan Dantata because of her role as his ‘mother’ (" Dantata" means "son of Tata”).

Alhassan was sent to a Qur'anic school (madrasah) in Bebeji and as his share of his father’s wealth (as so often happens), seemed to have vanished, he had to support himself. The life of the almajiri (Qur’anic student) is difficult, as he has to find food and clothing for himself and also for his malam (teacher) and at the same time read. Some simply beg while others seek paid work. Alhassan worked and even succeeded at the insistence of Tata in saving. His asusu, “money box” (a pottery vessel) purchased by Tata and set in the wall of the house can still be seen.

When he was about 15 years of age, Alhassan joined a Gonja bound caravan to see his mother. He purchased some items from Bebeji, sold half of them on the way and the rest in Accra. When he saw his mother, he was very delighted hoping she would allow him to live without doing any work since she was one of the wealthier local traders. After only a rest of one day, she took him to another malam and asked him to stay there until he was ready to return to Kano and he worked harder in Accra than he did in Bebeji. After the usual reading of the Qur’an, Alhassan Dantata had to go and beg for food for his malam, and himself. When he worked for money on Thursdays and Fridays, Alhassan Dantata would not be allowed to spend the money for himself alone, his malam always took the lion’s share (this is normal in Hausa society). After the visit, his mother sent him back to Bebeji where he continued his studies. Even though now a teenager, Tata continued to insist that he must save something everyday.

When he was still a teenager, great upheavals occurred in the Kano Emirate. This included the Kano Civil War (1893-1894) and the British invasion of the emirate (1903). During the Kano Civil war, Alhassan and his brothers were captured and sold as slaves, but they were able to buy back their freedom and return to Bebeji shortly afterwards.

Alhassan remained in Bebeji until matters had settled down and the roads were secure, only then did he set out for Accra, by way of Ibadan and Lagos (Ikko) and then by sea to Accra and then to Kumasi, Sekondi and back to Lagos. Alhassan was one of the pioneers of this route. For several years, he carried his kola by sea, using steamers; to Lagos where he usually sold it to Kano bound merchants. By this time, he was relatively wealthy.

In 1906, he began broadening his interests by trading in beads, necklaces, European cloth, etc. His mother, who had never remarried, died in Accra around 1908 and he thereafter generally restricted his operations to Lagos and Kano, although he continued to visit Accra.

CAREER

Thus far in his career, with most of his fellow long distance traders, he continued to live in one of the towns some distance from Kano City, only visiting the Birni for business purposes. Before Alhassan settled in Kano permanently, he visited Kano City only occasionally to either purchase or sell his wares. He did not own a house there, but was satisfied with the accommodation given to him by his patoma (land lord.). It was during the time of the first British appointed Emir of Kano; Abbas (1903-1919) that Alhassan decided to establish a home in Kano. He purchased his first house in the Sarari area (an extension of Koki). At that time there were no houses from the house of Baban Jaki (at the end of Koki) up to Kofar Mazugal. In fact the area was called Sarari because it was empty and nobody wanted that land. Alhassan built his first house on that land and was able thereafter to extend it freely.

In 1912, when the Europeans started to show an interest in the export of groundnut, they contacted the already established Kano merchants through the Emir, Abbas and their chief agent, Adamu Jakada. Some established merchants of Kano like Umaru Sharubutu, Maikano Agogo and others were approached and accepted the offer.

Later in 1918, Alhassan was approached by the Niger Company to help purchase groundnuts for them. He was already familiar with the manner by which people made fortunes by buying cocoa for Europeans in the Gold Coast. He responded and participated in the enterprise with enthusiasm, he had several advantages over other Kano business men: he could speak some English because of his contact with the people on the coast, thus he could negotiate more directly with the European traders for better prices. He also had accumulated a large capital and unlike other established Kano merchants, had only a small family to maintain, as he was still a relatively young man.

Alhassan had excellent financial management, was frugal and unostentatious. He knew some accounting and with the help of Alhaji Garba Maisikeli, his financial controller for 38 years, every kobo was accounted for every day. Not only that, Alhassan was hard working and always around to provide personal supervision of his workers. As soon as he entered the groundnut purchasing business, he came to dominate the field. In fact by 1922 he became the wealthiest businessman in Kano. Umaru Sharubutu and Maikano Agogo were relegated to the second and the third positions respectively.

When the British Bank of West Africa was opened in Kano in 1929, he became the first Kano businessman to utilize a bank account when he deposited twenty camel loads of silver coins. Shortly before his death, he pointed to sixty “groundnut pyramids” in Kano and said, “These are all mine”.

Alhassan became the chief produce buyer especially of groundnuts for the Niger Company (later U.A.C). It is said that he used to purchase about half of all the nuts purchased by U.A.C in northern Nigeria. Because of this, he applied for a license to purchase and export groundnuts in 1940 just like the U.A.C. However, because of the great depression and the war situation, it was not granted. Even Saul Raccah lost his license to export and import about this time because he did not belong to the Association of West African Merchants. In 1953-4 he became a licensed buying agent (L.B.A) that is, a buyer who sells direct to the marketing board instead of to another firm.

However, Alhassan had many business connections both in Nigeria and in other West African countries, particularly the Gold Coast. He dealt, not only in groundnuts, but also in other merchandise. He traded in cattle, kola, cloth, beads, precious stones, grains, rope and other things. His role in the purchase of kola nuts from forest areas of Nigeria for sale in the North was so great, that eventually whole “kola trains” from the Western Region were filled with his nuts alone.

When Alhassan finally settled in Kano, he maintained agents, mainly his relations, in other places. For instance Alhaji Bala, his brother, was sent to Lagos. Alhassan employed people, mainly Igbo, Yoruba and the indigenous Hausa people, as wage earners. They worked as clerks, drivers, and labourers. Some of his employees, especially the Hausas, stayed in his house. He was responsible for their marriage expenses. They did not pay rent and in fact, were regarded as members of his extended family. He sometimes provided official houses to some of his workers.

TEMPERAMENT AND CHARACTER

People’s opinion of Alhassan Dantata differed. To some people, he was a mutumin kirki (complete gentleman) who was highly disciplined and made money through hard work and honesty. He always served as an enemy to, or a breaker of hoarding. For instance, he would purchase items, especially grains, during the harvest time, when it was abundant at low prices. He would wait until the rainy season, (July or August) when there was limited supply in the markets or when grain merchants started to inflate prices.

He then moved to fill the markets with his surplus grains and asked a price lower than the current price in the markets by between 50 – 70%. In this way, he forced down prices. His anti- hoarding activities did not stop at grains and other consumer goods, but even to such items as faifai, igiya, babarma (Mat), dyed cloth, shuni, potash, and so on. However on the other hand, according to information collected in Koki, Dala, Qul-qul, Madabo, Yan Maruci e.t.c, Alhassan was viewed as a mugun mutum (wicked person). This was because some people expressed the view that Dantata undercut their prices simply to cripple his fellow merchants.

BUSINESS INTERESTS

He founded, with other merchants (attajirai), the Kano Citizens’ Trading Company, for industrial undertakings. In 1949, he contributed property valued at ₤10,200 (ten thousand, two hundred pounds) to the proposed Kano citizens trading company for the establishment of the first indigenous textile mill in Northern Nigeria. Near the end of his life he was appointed a director of the Railway Corporation.

In 1917, he started to acquire urban land in the non- European trading site (Syrian quarters) when he acquired two plots at an annual fee of ₤20. All his houses were occupied by his own people; relations, sons, servants, workers and so on. He never built a hotel for whatever purpose in his life and advised his children to do like wise. His numerous large warehouses in and around Kano metropolis were not for rent, rather he kept his own wares in them.

RELATIONSHIP WITH WOMEN

Because of his Islamic beliefs, Alhassan never transacted business with a woman of whatever age. His wife, Hajiya Umma Zaria, (mother of Aminu) was his chief agent among the women folk. The women did not have to visit her house. She established agents all over Kano city and visited them in turn. When she visited her agents, it was the duty of the agents to ask what the women in the ward wanted. Amina Umma Zaria would then leave the items for them. All her agents were old married women and she warned her agents to desist from conducting business with newly wedded girls. Umma Zaria dealt in the smallest household items, which would cost 2.5 d to sophisticated jewels worth thousands of pounds.

WAY OF LIFE, FOOD AND HEALTH

Though Alhassan became the wealthiest man in the British West African colonies, he lived a simple life. He fed on the same foodstuffs as any other individual, such as tuwon dawa da furar gero. He dressed simply in a white gown, a pair of white trousers (da itori), and underwear (yar ciki), a pair of ordinary local sandals, and sewn white cap, white turban and occasionally a malfa (local hat). He was said never to own more than three sets of personal clothing at a time. He never stayed inside his house all day and was always out doing something. He moved about among his workers joking with them, encouraging and occasionally giving a helping hand. He ate his meal outside and always with his senior workers like Garba Maisikeli and Alhaji Mustapha Adakawa.

Alhassan met fully established wealthy Kano merchants when he moved to Kano from the Kauye, like Maikano Agogo, Umaru Sharubutu, Salga and so on. He lived with them peacefully and always respected them. He avoided clashes with other influential people in Kano. He hated court litigation. He was in court only once, but before the final judgment the case was settled outside a Lagos court (it was a ₤10,000 civil suit instituted by one Haruna against him). He lived peacefully with the local authorities. Whenever he offended the authorities he would go quietly to solve the problems with the official concerned.

Alhassan enjoyed good health and was never totally indisposed throughout his active life. However, occasionally he might develop malaria fever and whenever he was sick, he would go to the clinic for treatment. Because of his simple eating habits, ordinary Hausa food two or three times a day and his always active mode of life, he never developed obesity. He remained slim and strong throughout his life. Alhassan had no physical defects and enjoyed good eye sight.

Alhassan was a devout Muslim. He was one of the first northerners to visit Mecca via England by mail boat in the early 1920s. He loved reading the Qur’an and Hadith. He had a personal mosque in his house and established a qur’anic school for his children. He maintained a full time Islamic scholar called Alhaji Abubakar (father of Malam Lawan Kalarawi, a renowned Kano public preacher).

He paid zakkat annually according to Islamic injunction and gave alms to the poor every Friday. He belonged to the Qadiriyya brotherhood.

Soon after the First World War he went on the pilgrimage to Mecca, via Britain, where he was presented to King George V.

EDUCATION INTERESTS

Alhassan Dantata respected people with qur’anic and other branches of Islamic learning, and helped them occasionally. He established a qur’anic school for his children and other people of the neighbourhood. He insisted that all his children must be well educated in the Islamic way. He appreciated also, functional western education, just enough to transact business (some arithmetic, simple accounting, Hausa reading and writing and spoken English).

Alhassan backed the establishment of a western style school in the Dala area for Hausas (i.e. non-Fulani) traders’ children in the 1930’s. The existence of a school in Bebeji (the only non-district headquarters in Kano to have one in the 1930’s) was probably due to his influence, although he could neither read nor write English. Alhassan could write beautiful Ajami, but could not speak or write Arabic, although he could read the Qur’an and other religious books with ease (this is very common in Hausa society). Most of the qur’anic reciter's could read very well, but could not understand Arabic. Alhassan Dantata knew some arithmetic-addition and subtraction and could use a ready reckoner. He also encouraged his children to learn enough western education to transact business, the need of his time. He established his own Arabic and English school in 1944, Dantata Arabic and English school.

POLITICS

He never became a politician in the true sense of the term. However, because of his enormous wealth, he was always very close to the government. He had to be in both the colonial government’s good books and maintain a position very close to the emirs of Kano. He was nominated to represent commoners in the reformed local administration of Kano and in 1950 was made a councillor in the emir’s council- the first non- royal individual to have a seat at the council. Other members of the council then were: Madakin Kano, Alhaji Muhammadu Inuwa, Walin Kano, Malam Abubakar Tsangaya, Sarkin Shanu, Alhaji Muhammadu Sani, Wazirin Kano Alhaji Abubakar, Makaman Kano Alhaji Bello Alhaji Usman Gwarzo, and the leader Alhaji Abdulllahi Bayero. Alhassan therefore was a member of the highest governing body of Kano in his time. He was also appointed to mediate between NEPU and NPC in Kano in 1954 together with Mallam Nasiru Kabara and other members. He joined no political party, but it is clear that he sympathised with the NPC.

DEATH AND LEGACY

In 1955, Alhassan fell ill and because of the seriousness of the illness, he summoned his chief financial controller, Garba Maisikeli and his children. He told them that his days were approaching their end and advised them to live together. He was particularly concerned about the company he had established (Alhassan Dantata & Sons). He asked them not to allow the company to collapse. He implored them to continue to marry within the family as much as possible. He urged them to avoid clashes with other wealthy Kano merchants. They should take care of their relatives, especially the poor among them. Three days later, he passed away in his sleep on Wednesday, 17th August, 1955 at 78. He was buried the same day in his house in Sarari ward, Kano. At the time of his death in August 1955, he was the wealthiest man of any race in West Africa.

It was and is rare for business organizations to survive the death of their founders in Hausa society. Hausa tradition is full of stories of former successful business families who later lost everything. In Kano city alone names like: Kundila of Makwarari, the wealthiest man at the end of nineteenth century, Maikano Agogo of Koki Ward, Umaru Sharubutu also of Koki Ward, Baban Jaji, Abdu Sarki of Zaitawa Ward, Madugu Indo of Adakawa, and others too numerous to mention here, were some of them.

Only Alhassan of Kano was likely to leave able heirs to continue his business in a grand way. The reason for this was that his heirs were interested in keeping the family name going and the employment of modern methods of book keeping, the only local merchant to do so at that time. Alhassan Dantata’s entire estate was subdivided according to Islamic law among the eighteen children who survived him. Alhassan’s descendants include Dr Aminu Dantata (son), Sanusi Dantata (son), Abdulkadir Sanusi Dantata (grandson), Dr Mariya Sanusi Dangote (granddaughter), Alhaji Aliko Dangote (great-grandson), Alhaji Tajudeen Aminu Dantata (great-grandson) and Alhaji Sayyu Dantata (great-great grandson). #HistoryVilleTHE UNFORGETTABLE NIGERIAN: WEALTH, WEALTH EVERYWHERE

Alhaji Alhassan Dantata (1877 - August 17, 1955) was a Nigerian businessman who was the wealthiest man in West Africa at the time of his death.

HERITAGE

Dantata's father was Abdullahi, a man from the village of Danshayi, near Kano. Dantata was born in Bebeji in 1877, one of several children of Abdullahi and his wife, both of whom were traders and caravan leaders.

Bebeji was on the Kano to Gonja (now in northern Ghana) and Kano to Lagos routes. The people of Bebeji, at least those from the Zango (campsite) were great traders. Bebeji was considered a miniature Kano. There was a saying which went “If Kano has 10 kolas, Bebeji has 20 halves" or in Hausa: "Birni tana da goro goma, ke Bebeji kina da bari 20".

The town attracted many people of different backgrounds in the 19th century, such as the Yorubas, Nupes, Agalawas, etc. It was controlled by the Sarki (chief) of Bebeji who was responsible for the protection of Kano from attack from the southwest.

Alhassan was born into an Agalawa trading family. His father Madugu Abdullahi was a wealthy trader and caravan leader while his mother was also a trader of importance in her own right enjoying the title of Maduga-Amarya. Abdullahi, in his turn, was a son of another prosperous merchant, Baba Talatin. It was he who brought the family from Katsina, probably at the beginning of the nineteenth century, following the death of his father, Ali.

Abdullahi already had a reputation of some wealth from his ventures with his father and therefore inherited his father’s position as a recognized and respected Madugu. Like his father, he preferred the Nupe and Gonja routes. He specialized in the exchange of Kano dyed cloth, cattle, slaves and so on for the kola of the Akan forest. Surprisingly, he had added cowries brought to the coast by European traders to the items he carried back to Kano.

BIRTH AND EARLY LIFE

Abdullahi continued to operate from Madobi until 1877 when having just set out for a journey to Gonja, his wife delivered in the Zango (campsite) of Bebeji. The child was a boy and after the usual seven days, he was named Alhassan. Abdullahi purchased a house in the town and left his nursing wife and child to await his return from Gonja. On his return, he decided to abandon Madobi and moved to Bebeji. Some say that the house that contains his tomb is still held by the family. The date of his death is unknown, but it was probably about 1885 when Alhassan was between seven and eight years of age. By then he had brothers and sisters – Shuaibu, Malam Jaji, Malam Bala, Malam Sidi and others.

The children were too young to succeed to their father’s position and to manage his considerable wealth. They all received their portion according to Islamic law. Maduga Amarya was known to be such a forceful character that nobody in the Zango would take her to wife. She therefore decided to leave the children in Bebeji, in the care of an old slave woman, while she moved to Accra where she became one of the wealthier Hausa traders.

The slave was known as "Tata" from which circumstance young Alhassan became known as Alhassan Dantata because of her role as his ‘mother’ (" Dantata" means "son of Tata”).

Alhassan was sent to a Qur'anic school (madrasah) in Bebeji and as his share of his father’s wealth (as so often happens), seemed to have vanished, he had to support himself. The life of the almajiri (Qur’anic student) is difficult, as he has to find food and clothing for himself and also for his malam (teacher) and at the same time read. Some simply beg while others seek paid work. Alhassan worked and even succeeded at the insistence of Tata in saving. His asusu, “money box” (a pottery vessel) purchased by Tata and set in the wall of the house can still be seen.

When he was about 15 years of age, Alhassan joined a Gonja bound caravan to see his mother. He purchased some items from Bebeji, sold half of them on the way and the rest in Accra. When he saw his mother, he was very delighted hoping she would allow him to live without doing any work since she was one of the wealthier local traders. After only a rest of one day, she took him to another malam and asked him to stay there until he was ready to return to Kano and he worked harder in Accra than he did in Bebeji. After the usual reading of the Qur’an, Alhassan Dantata had to go and beg for food for his malam, and himself. When he worked for money on Thursdays and Fridays, Alhassan Dantata would not be allowed to spend the money for himself alone, his malam always took the lion’s share (this is normal in Hausa society). After the visit, his mother sent him back to Bebeji where he continued his studies. Even though now a teenager, Tata continued to insist that he must save something everyday.

When he was still a teenager, great upheavals occurred in the Kano Emirate. This included the Kano Civil War (1893-1894) and the British invasion of the emirate (1903). During the Kano Civil war, Alhassan and his brothers were captured and sold as slaves, but they were able to buy back their freedom and return to Bebeji shortly afterwards.

Alhassan remained in Bebeji until matters had settled down and the roads were secure, only then did he set out for Accra, by way of Ibadan and Lagos (Ikko) and then by sea to Accra and then to Kumasi, Sekondi and back to Lagos. Alhassan was one of the pioneers of this route. For several years, he carried his kola by sea, using steamers; to Lagos where he usually sold it to Kano bound merchants. By this time, he was relatively wealthy.

In 1906, he began broadening his interests by trading in beads, necklaces, European cloth, etc. His mother, who had never remarried, died in Accra around 1908 and he thereafter generally restricted his operations to Lagos and Kano, although he continued to visit Accra.

CAREER

Thus far in his career, with most of his fellow long distance traders, he continued to live in one of the towns some distance from Kano City, only visiting the Birni for business purposes. Before Alhassan settled in Kano permanently, he visited Kano City only occasionally to either purchase or sell his wares. He did not own a house there, but was satisfied with the accommodation given to him by his patoma (land lord.). It was during the time of the first British appointed Emir of Kano; Abbas (1903-1919) that Alhassan decided to establish a home in Kano. He purchased his first house in the Sarari area (an extension of Koki). At that time there were no houses from the house of Baban Jaki (at the end of Koki) up to Kofar Mazugal. In fact the area was called Sarari because it was empty and nobody wanted that land. Alhassan built his first house on that land and was able thereafter to extend it freely.

In 1912, when the Europeans started to show an interest in the export of groundnut, they contacted the already established Kano merchants through the Emir, Abbas and their chief agent, Adamu Jakada. Some established merchants of Kano like Umaru Sharubutu, Maikano Agogo and others were approached and accepted the offer.

Later in 1918, Alhassan was approached by the Niger Company to help purchase groundnuts for them. He was already familiar with the manner by which people made fortunes by buying cocoa for Europeans in the Gold Coast. He responded and participated in the enterprise with enthusiasm, he had several advantages over other Kano business men: he could speak some English because of his contact with the people on the coast, thus he could negotiate more directly with the European traders for better prices. He also had accumulated a large capital and unlike other established Kano merchants, had only a small family to maintain, as he was still a relatively young man.

Alhassan had excellent financial management, was frugal and unostentatious. He knew some accounting and with the help of Alhaji Garba Maisikeli, his financial controller for 38 years, every kobo was accounted for every day. Not only that, Alhassan was hard working and always around to provide personal supervision of his workers. As soon as he entered the groundnut purchasing business, he came to dominate the field. In fact by 1922 he became the wealthiest businessman in Kano. Umaru Sharubutu and Maikano Agogo were relegated to the second and the third positions respectively.

When the British Bank of West Africa was opened in Kano in 1929, he became the first Kano businessman to utilize a bank account when he deposited twenty camel loads of silver coins. Shortly before his death, he pointed to sixty “groundnut pyramids” in Kano and said, “These are all mine”.

Alhassan became the chief produce buyer especially of groundnuts for the Niger Company (later U.A.C). It is said that he used to purchase about half of all the nuts purchased by U.A.C in northern Nigeria. Because of this, he applied for a license to purchase and export groundnuts in 1940 just like the U.A.C. However, because of the great depression and the war situation, it was not granted. Even Saul Raccah lost his license to export and import about this time because he did not belong to the Association of West African Merchants. In 1953-4 he became a licensed buying agent (L.B.A) that is, a buyer who sells direct to the marketing board instead of to another firm.

However, Alhassan had many business connections both in Nigeria and in other West African countries, particularly the Gold Coast. He dealt, not only in groundnuts, but also in other merchandise. He traded in cattle, kola, cloth, beads, precious stones, grains, rope and other things. His role in the purchase of kola nuts from forest areas of Nigeria for sale in the North was so great, that eventually whole “kola trains” from the Western Region were filled with his nuts alone.

When Alhassan finally settled in Kano, he maintained agents, mainly his relations, in other places. For instance Alhaji Bala, his brother, was sent to Lagos. Alhassan employed people, mainly Igbo, Yoruba and the indigenous Hausa people, as wage earners. They worked as clerks, drivers, and labourers. Some of his employees, especially the Hausas, stayed in his house. He was responsible for their marriage expenses. They did not pay rent and in fact, were regarded as members of his extended family. He sometimes provided official houses to some of his workers.

TEMPERAMENT AND CHARACTER

People’s opinion of Alhassan Dantata differed. To some people, he was a mutumin kirki (complete gentleman) who was highly disciplined and made money through hard work and honesty. He always served as an enemy to, or a breaker of hoarding. For instance, he would purchase items, especially grains, during the harvest time, when it was abundant at low prices. He would wait until the rainy season, (July or August) when there was limited supply in the markets or when grain merchants started to inflate prices.

He then moved to fill the markets with his surplus grains and asked a price lower than the current price in the markets by between 50 – 70%. In this way, he forced down prices. His anti- hoarding activities did not stop at grains and other consumer goods, but even to such items as faifai, igiya, babarma (Mat), dyed cloth, shuni, potash, and so on. However on the other hand, according to information collected in Koki, Dala, Qul-qul, Madabo, Yan Maruci e.t.c, Alhassan was viewed as a mugun mutum (wicked person). This was because some people expressed the view that Dantata undercut their prices simply to cripple his fellow merchants.

BUSINESS INTERESTS

He founded, with other merchants (attajirai), the Kano Citizens’ Trading Company, for industrial undertakings. In 1949, he contributed property valued at ₤10,200 (ten thousand, two hundred pounds) to the proposed Kano citizens trading company for the establishment of the first indigenous textile mill in Northern Nigeria. Near the end of his life he was appointed a director of the Railway Corporation.

In 1917, he started to acquire urban land in the non- European trading site (Syrian quarters) when he acquired two plots at an annual fee of ₤20. All his houses were occupied by his own people; relations, sons, servants, workers and so on. He never built a hotel for whatever purpose in his life and advised his children to do like wise. His numerous large warehouses in and around Kano metropolis were not for rent, rather he kept his own wares in them.

RELATIONSHIP WITH WOMEN

Because of his Islamic beliefs, Alhassan never transacted business with a woman of whatever age. His wife, Hajiya Umma Zaria, (mother of Aminu) was his chief agent among the women folk. The women did not have to visit her house. She established agents all over Kano city and visited them in turn. When she visited her agents, it was the duty of the agents to ask what the women in the ward wanted. Amina Umma Zaria would then leave the items for them. All her agents were old married women and she warned her agents to desist from conducting business with newly wedded girls. Umma Zaria dealt in the smallest household items, which would cost 2.5 d to sophisticated jewels worth thousands of pounds.

WAY OF LIFE, FOOD AND HEALTH

Though Alhassan became the wealthiest man in the British West African colonies, he lived a simple life. He fed on the same foodstuffs as any other individual, such as tuwon dawa da furar gero. He dressed simply in a white gown, a pair of white trousers (da itori), and underwear (yar ciki), a pair of ordinary local sandals, and sewn white cap, white turban and occasionally a malfa (local hat). He was said never to own more than three sets of personal clothing at a time. He never stayed inside his house all day and was always out doing something. He moved about among his workers joking with them, encouraging and occasionally giving a helping hand. He ate his meal outside and always with his senior workers like Garba Maisikeli and Alhaji Mustapha Adakawa.

Alhassan met fully established wealthy Kano merchants when he moved to Kano from the Kauye, like Maikano Agogo, Umaru Sharubutu, Salga and so on. He lived with them peacefully and always respected them. He avoided clashes with other influential people in Kano. He hated court litigation. He was in court only once, but before the final judgment the case was settled outside a Lagos court (it was a ₤10,000 civil suit instituted by one Haruna against him). He lived peacefully with the local authorities. Whenever he offended the authorities he would go quietly to solve the problems with the official concerned.

Alhassan enjoyed good health and was never totally indisposed throughout his active life. However, occasionally he might develop malaria fever and whenever he was sick, he would go to the clinic for treatment. Because of his simple eating habits, ordinary Hausa food two or three times a day and his always active mode of life, he never developed obesity. He remained slim and strong throughout his life. Alhassan had no physical defects and enjoyed good eye sight.

Alhassan was a devout Muslim. He was one of the first northerners to visit Mecca via England by mail boat in the early 1920s. He loved reading the Qur’an and Hadith. He had a personal mosque in his house and established a qur’anic school for his children. He maintained a full time Islamic scholar called Alhaji Abubakar (father of Malam Lawan Kalarawi, a renowned Kano public preacher).

He paid zakkat annually according to Islamic injunction and gave alms to the poor every Friday. He belonged to the Qadiriyya brotherhood.

Soon after the First World War he went on the pilgrimage to Mecca, via Britain, where he was presented to King George V.

EDUCATION INTERESTS

Alhassan Dantata respected people with qur’anic and other branches of Islamic learning, and helped them occasionally. He established a qur’anic school for his children and other people of the neighbourhood. He insisted that all his children must be well educated in the Islamic way. He appreciated also, functional western education, just enough to transact business (some arithmetic, simple accounting, Hausa reading and writing and spoken English).

Alhassan backed the establishment of a western style school in the Dala area for Hausas (i.e. non-Fulani) traders’ children in the 1930’s. The existence of a school in Bebeji (the only non-district headquarters in Kano to have one in the 1930’s) was probably due to his influence, although he could neither read nor write English. Alhassan could write beautiful Ajami, but could not speak or write Arabic, although he could read the Qur’an and other religious books with ease (this is very common in Hausa society). Most of the qur’anic reciter's could read very well, but could not understand Arabic. Alhassan Dantata knew some arithmetic-addition and subtraction and could use a ready reckoner. He also encouraged his children to learn enough western education to transact business, the need of his time. He established his own Arabic and English school in 1944, Dantata Arabic and English school.

POLITICS

He never became a politician in the true sense of the term. However, because of his enormous wealth, he was always very close to the government. He had to be in both the colonial government’s good books and maintain a position very close to the emirs of Kano. He was nominated to represent commoners in the reformed local administration of Kano and in 1950 was made a councillor in the emir’s council- the first non- royal individual to have a seat at the council. Other members of the council then were: Madakin Kano, Alhaji Muhammadu Inuwa, Walin Kano, Malam Abubakar Tsangaya, Sarkin Shanu, Alhaji Muhammadu Sani, Wazirin Kano Alhaji Abubakar, Makaman Kano Alhaji Bello Alhaji Usman Gwarzo, and the leader Alhaji Abdulllahi Bayero. Alhassan therefore was a member of the highest governing body of Kano in his time. He was also appointed to mediate between NEPU and NPC in Kano in 1954 together with Mallam Nasiru Kabara and other members. He joined no political party, but it is clear that he sympathised with the NPC.

DEATH AND LEGACY

In 1955, Alhassan fell ill and because of the seriousness of the illness, he summoned his chief financial controller, Garba Maisikeli and his children. He told them that his days were approaching their end and advised them to live together. He was particularly concerned about the company he had established (Alhassan Dantata & Sons). He asked them not to allow the company to collapse. He implored them to continue to marry within the family as much as possible. He urged them to avoid clashes with other wealthy Kano merchants. They should take care of their relatives, especially the poor among them. Three days later, he passed away in his sleep on Wednesday, 17th August, 1955 at 78. He was buried the same day in his house in Sarari ward, Kano. At the time of his death in August 1955, he was the wealthiest man of any race in West Africa.

It was and is rare for business organizations to survive the death of their founders in Hausa society. Hausa tradition is full of stories of former successful business families who later lost everything. In Kano city alone names like: Kundila of Makwarari, the wealthiest man at the end of nineteenth century, Maikano Agogo of Koki Ward, Umaru Sharubutu also of Koki Ward, Baban Jaji, Abdu Sarki of Zaitawa Ward, Madugu Indo of Adakawa, and others too numerous to mention here, were some of them.

Only Alhassan of Kano was likely to leave able heirs to continue his business in a grand way. The reason for this was that his heirs were interested in keeping the family name going and the employment of modern methods of book keeping, the only local merchant to do so at that time. Alhassan Dantata’s entire estate was subdivided according to Islamic law among the eighteen children who survived him. Alhassan’s descendants include Dr Aminu Dantata (son), Sanusi Dantata (son), Abdulkadir Sanusi Dantata (grandson), Dr Mariya Sanusi Dangote (granddaughter), Alhaji Aliko Dangote (great-grandson), Alhaji Tajudeen Aminu Dantata (great-grandson) and Alhaji Sayyu Dantata (great-great grandson).

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Together we can save Ghana's economy - Mahama as he calls on all to consume local foods

Together we can save Ghana’s economy – Mahama as he calls on all to consume local foods

Former President John Dramani Mahama has expressed hope that the economy will get better. In his view, with unity, Ghanaians can turn the fortunes of the economy around to benefit all. Delivering an address at the University of Professional Studies, Accra (UPSA) on Thursday October 27, said “together we can save Ghana and build the Ghana we want regardless of how bad the situation is. I still…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Jordan Ayew tackle: Premier League explains why Crystal Palace forward was not sent off against Everton

Ghana forward Jordan Ayew was fortunate to escape with a red card after a ‘reckless’ tackle on Antony Gordon during Crystal Palace match against Everton on Thursday night.

During the first half, Ayew launched himself into a wild scissor-like challenge on Everton player Anthony Gordon, which earned him a yellow card from referee Anthony Taylor.

Many had described the Ghanaian attacker’s tackle on the player as ‘reckless’.

But after VAR review, no action was taken against the former Marseilles striker as the yellow card was maintained.

The decision was assessed by VAR official, Mike Dean, but it was decided that it did not meet the threshold for a red card.

The Ghanaian international started and lasted the entire duration as his outfit suffered a 3-2 defeat at Everton.

The visitors took the lead through Jean-Philippe Mateta in the 21st minute before Jordan Ayew added the second goal in the 36th minute.

After the break, Everton fought back to secure the three maximum points to survive relegation.

Goals from Michael, Richarlison and Dominic Calvert-Lewin were enough for the Toffees to win the much-anticipated game.

Jordan Ayew has scored three goals and provided three assists in 31 Premier League games this season.

He is expected to join the Black Stars team for the upcoming 2023 Africa Cup of Nations.

Ghana will play Madagascar on June 1 before traveling to Central Africa Republic for their second group game.

source: https://footballghana.com/

0 notes

Text

Fortune Thursday Confirmed Two Sure For 15/06/2023

Fortune Thursday Confirmed Two Sure For 15/06/2023 Fortune Thursday Confirmed Two Sure for today is ready and we at Abc Naija Lotto are very sure our fortune thursday lotto banker will drop live on today’s lotto draw. Lotto vendor one banker fortune – live banker for today fortune thursday facebook, Here are the best two sure and banker for Fortune draw on 03 November 2022. Fortune 2sure lotto…

View On WordPress

#2 live banker for today lotto#fortune 2sure#Fortune Ghana lotto forecast for today#Fortune ghana lotto live#Fortune Lottery in Nigeria#Fortune Prediction Today#Fortune Thursday Confirmed Two Sure#fortune thursday lotto banker#Ghana Fortune Lotto 2-Sure#Ghana Fortune Lotto 3direct#ghana fortune lotto banker#ghana Fortune lotto forecast#Ghana Fortune Lotto Long Perm#Ghana Fortune Lotto Perm7#Ghana Fortune Weekly Lotto#ghana live banker#Ghana Lotto Prediction for Fortune#live Ghana Fortune banker#one banker fortune#Prediction for Fortune Weekly#sure Fortune winning numbers

0 notes

Text

Fortune Lotto Thursday Result Today, Check Ghana Fortune Lotto Thursday Result, Winning Numbers Here

Fortune Lotto Thursday Result Today, Check Ghana Fortune Lotto Thursday Result, Winning Numbers Here

Fortune Lotto Thursday Result Today Players can check the Fortune Lotto Thursday Result Today 1st July 2021 on our page. We have updated Fortune Lotto Thursday Result Today, Fortune thursday result winning numbers for the latest draw. If you have participated in the game, you can check the Fortune Lotto Thursday Result Today from the table provided below. The Fortune Lotto Thursday Result will…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Tommy Annan Forson - A journalist in the revolutionary era.

He has a disarming charm that calms anyone he engages. He is down to earth, assertive and jolly witty. That was my first impression of Tommy Annan Forson. Last Thursday was world radio day and there was, undoubtedly, no other personality, within the press fraternity, more qualified to speak about the history of radio in Ghana than Mr Annan Forson. It was an absolute honour to have him grace our studio for an hour-long interview on Straight Talk, Class 91.3FM.

His story is unorthodox. He had no formal media training. In fact, he did not attend sixth form, neither did he receive a university education. Tommy’s entry into radio was purely by chance. His life revolved around that little wireless device he listened to fervently. And one fine day, he found a radio show so fascinating that it led him to the headquarters of the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC), where he met with the anchor. He left with a life-changing opportunity to become a journalist. That was the beginning of a legendary career. Tommy admits he didn’t earn a place at the state-owned broadcasting corporation by virtue of academic competence but solely based on exceptional talent and enormous potential.

Journalism in an era of military rule.

Seated comfortably, exuding grace, Tommy recounted sombre days as a journalist during the era of military rule. He was going about his regular duties on a normal day at work when, suddenly, the military began to open fire from every direction – shooting through the glass straight into the studio, through the bathroom windows – everywhere! A coup was in motion and Tommy was at the heart of it.

He, along with an elite staff of journalists, administered the voice of the Republic and were the gatekeepers of the most influential democratic institution in Ghana – the fourth estate. The GBC staff, at gun point, against their wishes, had allowed a previous set of armed officers to broadcast a coup declaration which was replayed every thirty minutes.

Fortunately, one of the staff, during the ambush, broke through the steels of fear that imprisoned the entire press fraternity and began shouting “we are staff!”. He then brought out his ID card and they were commanded to come out of their hiding places. Luckily, the bullets didn’t hit anyone. Tommy, together with his colleagues, were lined up against the wall. The instruction from an officer, speaking through a walkie-talkie to the hearing of the journalists, was “shoot them!”.

“That was when I realised your soul can leave the body, seek permission from Jesus Christ if there’s space up there, and then if there isn’t, return”, Tommy said light-heartedly.

Fortunately, the walkie-talkies were all connected to one frequency and Captain Courage E. K. Quashigah, the commanding officer, ordered the armed officers to desist from murdering the journalist. “Stand down, they’re only civilians”, Quashigah yelled.

Tommy and his fellow journalists were held captive at the GBC headquarters for a few more days, snacking on biscuits, quaffing beer and eating kenkey.

For the next few months, GBC remained under the watchful eye of the revolutionaries. Flight Lieutenant Rawlings once called and instructed that a personality should be taken off the airwaves for speaking in an American accent. Western music was also generally frowned upon and the GBC were ordered to play African music as often as possible.

Workers who arrived at the premises of GBC, with vehicles, had to flash their car lights a certain number of times to indicate that they were staff. Sometimes, they were given a passwords that were used as modes of recognition to identify staff. “I had to go home memorising a passwords because once you’re not able to respond with a correct code, you’re in trouble” Tommy said.

There was a day Tommy arrived at work at a time a guard stationed at the main gate was leaving post. It was the rule then for an armed officer to offload bullets from his/her rifle, put it in the air and fire to prove it was empty. The guard, assuming the rifle was empty, pointed it at Tommy and shot. There happened to be a bullet in the rifle that missed his ear by a whisker. “I just dropped my records. I didn’t know where I was walking to but the next thing I knew I was home.” Tommy said. He still looked terrified narrating the incident.

Tommy Annan Forson left the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation after 16 years of service.

Authored by V. L. K. Djokoto

0 notes

Text

A Look at the November 2019 LSAT

Interrupting everyone’s holiday festivities, scores for the November 2019 LSAT were released last Thursday. These scores brought holiday joy to some (those who were satisfied with their scores; LSAT instructor dorks, such as yours truly, who get a shiny new LSAT to play with) and despair to others (those who were decidedly less than satisfied with their scores; those same LSAT instructor dorks who have to translate their thoughts on the exam into lengthy blog posts). But whether this exam wrought good or bad tidings, we’re going to go over it, as we do following the release of every published LSAT. So let’s get to some quick hits on the November exam …

• Following most LSATs, there’s an early and near-universal consensus on what was the hardest part of the exam. Think the so-called “flower game” following the September 2019 exam. No so for the November test. Some thought the passage on peptides and microchips was the most dyspeptic. Some thought the last game on representatives from various companies represented the greatest challenge. Still others threw up their hands and declared the whole thing difficult.

For me at least, I thought the final game was the most difficult part of this exam. That game involved the scheduling of four representatives’ visits to factories in the three far-flung countries of France, Ghana, and India. We call these games “repeat” tiered ordering games; we had to schedule the order of the visitations three separate times (requiring us to “repeat” the ordering process three times, essentially).

Except there was a major twist in this game — representatives could visit some factories more than once over the four-month span. In most of these “repeat” tiered ordering games, each player goes exactly once each time you order the players. On this game, each representative could go as many as three times or as few as zero times each time you ordered them. Which meant there was a lot more to keep track of as you worked through the game.

As with almost any game though, a bit of work upfront made things more manageable. There was a pretty straightforward way to make two scenarios, each of which filled out part of your set up. These answered a few of the questions. There was also a pretty important — but difficult to make — deduction regarding the distribution of players to each country. Partly because players who visited the factory in France could not also visit the factory in India (one can apparently see both London and France, but not Mumbai and France, according to the dictates of this game), there were only four possible distribution of players to France and India. Trying to answer the remaining questions without having determined these distributions would have exposed you (and your underpants).

• Speaking of games, the major theme of this set was players being underbooked — which is our way of saying that the games gives you fewer players than places to put those players. We, presciently, noted this trend before this exam, and even predicted that there would be an underbooked game on this test. Before we get too self-satisfied, however, we should note that this wasn’t the most inspired prediction — nearly every recent published test included at least one underbooked game.

But even we weren’t ready for this set of games, in which three of the four games were underbooked. Aside from the company representative game we discussed above (in which four players had to fill twelve slots in your set-up), the first game (in which five agents had to schedule a meeting over seven months) and the third game (in which five technicians had to be divided into three two-person groups) were underbooked as well. Aside from some tricky language in the first game (which relied on the distinction between being the third agent to go versus going in the third month, for instance — much like the television programming game from the December 2011 exam), these games were much more manageable than the final game.

•The other unifying feature of these games? Scenarios. If you determined that each of these games could only play out in a few different ways, and you made some pre-question deductions about what would happen in each possible iteration of the game, all four games on this section could be finished expediently. This isn’t a unique feature of this game set. For whatever reason, almost every game on recent exams is easier with a good set of scenarios. By my count, only one out of the last thirty-six published games was easier without scenarios. So, like, no doy, if you’re preparing for any upcoming exam, spend a significant chuck of your study time figuring out when and how to make these scenarios.

• Nothing in the two scored Logical Reasoning sections struck me as difficult as that final game. Although every LR section has at least a few questions that will leave you gobsmacked, these sections were, on balance, very fair. Here’s how the 51 questions got divvied up …

(The “Avg. freq.” refers to how many of these questions appeared, on average, on each published LSAT from June 2017 to November 2019)

Not too far off from our predictions, but we did dramatically underestimate how many Soft Must Be True questions there would be. Eight Soft Must Be True questions is the most since the June 2017 test, in fact. The prominence of that question type has been trending down in the last couple years, but perhaps the test writers were banking a ton of them to spring upon unsuspecting November test takers.

Principle questions also made a big showing on this exam, with two Soft Must Be True Principle questions and three Strengthen Principle questions. Principles have become increasingly prevalent on recent exams, so make sure you know how to identify and tackle Soft Must Be True and Strengthen Principle questions, since the right approach makes these among the more predictable and anticipatable questions.

• Speaking of other recurrent themes on these LR sections, causation was a huge factor on this test. I counted ten separate questions that involved cause and effect. We should greet the appearance of cause-and-effect relationships with open arms in LR. When the author concludes that a cause-and-effect relationship exists, it’s nearly always a flawed conclusion. When we’re asked to strengthen or weaken a cause-and-effect relationship, there are only a few ways an answer choices might do either. Identifying causation makes these LR questions significantly more manageable, so LR sections that feature this much causation shouldn’t be too tricky.

But what made some of these questions a little challenging was the fact that the test writers seemed to go out of their way to hide the cause and effect. Rather than use classic cause-and-effect words like “results in” or “due to,” they hid the causation with more subtle language like “attract” or “attributable to.” To make sure you’re catching these hidden cause-and-effect relationships, you should always ask yourself if an argument is asserting that one thing is producing a change. Such assertions will always present cause-and-effect relationships — the first thing is causing that change. There are myriad ways to show that one thing is changing something else without resorting to obviously causal words like “causes” or “leads to,” so focus less on the language (although strong, active verbs like “increases,” “promotes,” “reduces,” etc. can be great clues that there’s an asserted cause-and-effect relationship) and more on whether the argument claims that one thing is an agent of change.

• Conditional reasoning, by contrast, was underemphasized on this exam — with only eight questions involving conditional statements or quantifiers. The questions that did feature these concepts, were relatively straightforward, fortunately.

• No one goes to the LSAT for entertainment, but the test writers can usually be counted on for at least one truly dada LR question. I didn’t find any here, unless you found one question’s reference to an “all-cheeseburger diet” whimsical. The test writers were apparently binging HBO programs from this last year, however, with questions referencing both dire wolves and Chernobyl.

• I thought the hardest LR question was a Strengthen question that came late in the second LR section of the released exam. In that question, researchers surmised that the consumption of turmeric in curry helped stave off the cognitive decline of some people in Singapore (this, by the way, was the second question in as many years to discuss the cognitive benefits of turmeric, with a question about turmeric’s ability to prevent Alzheimer’s appearing in December 2017). Apparently the elderly of Singapore who consume curry received much higher scores on cognitive tests than those Singaporeans who did not mess with curry. The researchers then claimed that this relationship was “the strongest for the elderly Singapore residents of Indian ethnicity.”

• An out-of-nowhere reference to people of Indian descent in a question about curry felt, at least to this non-Indian dude, extremely problematic. But if that potentially racist part of the question struck you the same way, it at least pointed us to the right answer. Answering Strengthen questions is always easier if you understand why the argument presented is flawed; the right answer will typically fix that problem. This particular question was difficult because it was flawed in about eighteen different ways. But focusing on that reference to Indian-Singaporeans would have directed us to a major flaw — even if the turmeric in curry does cause people to retain their cognitive faculty into their dotage, why would this relationship be more pronounced for Indian people? The right answer presented a reason why — the curries that Indian-Singaporeans consume have more turmeric than other curries, so the fact that the Indian-Singaporeans are able to stay even sharper in their twilight years reinforces the claim that turmeric can keep elderly people sharp.(Now, the right answer just said “Indian curries” have more turmeric, requiring us to make perhaps another problematic assumption that Indian-Singaporeans who consume curries consume mostly Indian curries … but I’ll leave any further discussions of the LSAT’s cultural sensitivity to y’all.)

• Although Reading Comprehension has been only getting more brutal in recent years, I thought most passages were tolerable here. In the first passage, the author had a major bone to pick to the dull, ahistorical presentation of early-twentieth-century nonfiction films at film festivals. Many noted how over-written the last sentence of this passage was (“It ill behooves us alleged early film lovers to forsake their insights today.”). But so long as you were not left bewildered or bedeviled by the phrase “ill behooved,” the questions were all pretty straightforward. Most were about the author’s claim that we shouldn’t simply display the same kind of films together simply because they’re similar, but we should instead take lessons from how people in the early twentieth century would have programmed those films.

The second passage — the inevitable law passage — should have sounded very familiar to test takers. Much like the legal passage in the September 2019 exam, this one was about how international legal norms and guidelines will have to reckon with climate change. In the November passage, the author complained that the international guidelines that help nations form treaties regarding waterways that pass through multiple countries are inadequate because they don’t consider how climate change will affect those waterways. The questions focused almost exclusively on two claims from the passage: that the guidelines were intended to reflect norms already established by international courts and practices, and that apportionment of water to different countries based on proportional shares might be more fair and flexible than what the guidelines currently prescribe. If you caught these two ideas, the passage would have been … ahem … smooth sailing.

We discussed the third passage — what many alleged to be the hardest passage in the section, about the use of peptides to make microchips smaller — last Thursday. Reading this one again, I was struck by how many extraneous details were in the passage. Most questions in this passage did not require a deep understanding of every last detail mentioned in the passage. As we discussed in this blog post, that’s not uncommon for science passages. They’ll inundate you with details, but focus on the big picture. Usually that’s enough to answer the questions. And if they happen to ask you about a very small detail, you can always go back to the passage to get that answer.

The final passage, the comparative one, fortunately had only five questions. Both passages referred to the Whorfian hypothesis (which, coincidentally but helpfully, was a plot point in the movie Arrival) that one’s native language constrains their thoughts, and both authors looked at that hypothesis somewhat skeptically. The questions could have been much more difficult than they were, but most focused on the general relationship between the two passages.

• Finally, let’s discuss the curve of this exam again …

(Each number refers to number of questions you can answer incorrectly and still earn the respective score)

I can’t argue with the numbers the psychometricians who scaled this exam relied on, but this felt like a pretty stingy curve to me. When the hardest part of a test is a logic game, we can usually count on an at least -12 curve for a 170. For instance, we got a -13 curve in September 2019, when everyone thought the hardest part of the exam was the “flower game.” Obviously, not everyone who took this November exam shared my opinion that the fourth game was the hardest part of the test. But I was genuinely surprised to look at this curve after doing that fourth game — I thought that game was a bit more difficult than the “flower game” from September, so I expected a fairly generous curve to score a 165 or 170.

The curve rounded out to be more forgiving for those scoring in the 160 and below. But this would have been a particularly annoying test to those scoring in the 160s who were hoping to crack into the 170s. If that describes you (and if you made it through all 2300 words of this blog, I’m guessing you’re pretty dedicated to earning that high score), I would definitely recommend taking the LSAT again. If you didn’t hit your target score this time, another exam with a slightly more generously curved exam (or a slightly less difficult final game) might allow you to hit it next time.

A Look at the November 2019 LSAT was originally published on Blueprint LSAT Blog

0 notes

Text

Leak Fortune Prediction - Original Lotto Forecasters

Leak Fortune Prediction – Original Lotto Forecasters

Leak Fortune Prediction – Original Lotto Forecasters Leak fortune prediction for today 7/11/2019 was done by our original lotto forecasters and it’s the best sure lotto forecast to win fortune thursday lotto banker. Ghana Fortune Thursday Lotto Forecast. Best Ghana Lotto Forecaster for Today Game. Thursday Forecast for Ghana Lotto. (more…)

View On WordPress

#Best Ghana Lotto Forecaster#best lotto house#Fortune forecasting#FORTUNE LOTTO Fortune Thursday best banker#Fortune thursday best banker#Ghana Fortune Thursday Lotto Forecast#ghana lotto banker#GHANA LOTTO Forecasting#Leak fortune prediction#Lotto banker for today#original lotto forecasters#Thursday Forecast#Thursday Ghana Fortune#Todays Lotto Winning Numbers

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes