#TheIslandHopperarticle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Island Hopper

January 2017

With the retirement of so many classic airliner types – even the mighty 747 is now fully established on the endangered species list – there is less and less out there for a hardcore airline enthusiast. The Island Hopper, covering a big chunk of the Pacific Ocean with five stops on the way from Honolulu to Guam, remains a must-have.

Air Micronesia – Air Mike for short – was established in 1968 by Continental Airlines to serve the chain of US-administered islands that run across the Pacific, starting with Majuro in the Marshall Islands and through Micronesia all the way to the Philippines, with a focus on the US trust territory of Guam. Air Mike began operations with a pair of Boeing 727-100s with Teflon-coated undersides as some of the runways were made of coral. Juju was a full passenger aircraft with 117 seats and Muju was a combi with half the main deck for cargo plus seventy-eight passengers. Continental’s airline-within-an-airline provided an essential link to the outside world that previously took weeks by occasional ship to other ports. The 727-100s and later -200s had been replaced by Boeing 737-800s by the time Continental merged with United Airlines in December 2010; the flight was renumbered UA154 from Honolulu to Guam and UA155 in the opposite direction back to Hawaii. Otherwise the Island Hopper still runs pretty much as it has done since the late 60s.

Presently, the flight operates on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and routes from Honolulu to Guam via Majuro, Kwajalein, Kosrei, Pohnpei, and Chuuk a.k.a. Truk. (Kosrae is omitted on Wednesdays.) The first two stops are in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the latter three are in the Federated States of Micronesia. Both are island countries that were granted independence from the United States in 1986. Guam itself is part of the United States, albeit an “unincorporated and organised territory” rather than an actual state. The stops along the way are in some of the most remote places in the world that have jet service, small and isolated islands and atolls in the middle of the world’s greatest ocean.

THE JOURNEY BEGINS

I was planning my route home from visiting family and friends in Australia back to England and realised this might be a good chance to ride the Island Hopper. A one-way trip booked as a stand-alone ticket was over £900, so initially it was out of the question, but I realised I would of course need to get out of Guam somehow anyway, so I circled back to United’s website, this time clicking the “multi-city” option. I combined Honolulu to Guam with Guam to Tokyo and Tokyo to San Francisco (with the Tokyo to Frisco leg having the added bonus of being operated by a soon-to-be-retired 747); the whole lot came in at under £800 with the Island Hopper leg itself a very attractive £234. After checking I could get a positioning leg up from Sydney the day before on Qantas at a reasonable fare, I pressed the buy button. I had to add in hotels at both ends because the Island Hopper is a fourteen hour flight that leaves Honolulu at 0725, no point in starting tired; and arrives into Guam at 1755 scheduled, too late for anything meaningful to connect onwards, at least with United. (After booking, a fellow avgeek pointed out that United fly later the same evening on to Manila via Palau and this tag-on is considered a continuation of the Island Hopper, but six sectors in a day is enough, especially with those two extra legs being in darkness.)

My alarm went off at 0500 in Waikiki Beach and after a quick shower I was in a cab at 0515 and at the terminal before 0600. I had a chat with a United employee about my mission and he thanked me for being early, but T minus one hour twenty-five didn’t seem over-cautious: for one thing I wasn’t sure if the Island Hopper counted as an international flight and hence what kind of formalities to expect (turns out it is considered international but as with all US-originating flights, there are no exit controls). I was also anxious that a United ticket agent didn’t spot that I was flying via the longest possible route to Guam and rebook me onto a nonstop (still a not-inconsiderable eight hours). All avgeeks know that overly helpful ticket agents can pose an existential threat to any deliberately multistop routing.

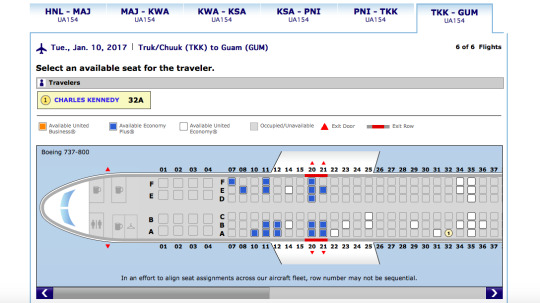

Surprisingly, when I checked in online the night before and again at the airport self-service kiosk, it was possible to select a different seat for each of the six legs. In fact for the first four legs, 32A had empty seats next to it, and for the last two, the flight was so full that moving wouldn’t have made any difference so I stuck with the same seat all the way to Guam. Nonetheless the kiosk spat out six boarding passes, one for each leg – and for a paper collector, this was cause for minor celebration.

Security was fast and easy and I enjoyed the walk to gate nine with the sides of the building open to the elements. Looking at the departures board (showing the Island Hopper’s destination as “Majuro”), the scale of Hawaii’s appeal to Japanese tourists was obvious, with ten departures to Tokyo Narita alone scheduled between before midday.

The first light of dawn was in the east as we were called to board our Boeing 737-824. The interior was brand new and very comfortable, with personal TV screens on each seatback. As the day progressed I had a few chats with the pilots about the aeroplanes used, and learned that although Air Mike had dedicated aircraft, the present-day Island Hoppers are drawn from the United Airlines 737-800 pool and rotated back to the mainland after a few months as the salty atmosphere over the Pacific is corrosive to metal birds; such a pattern minimises the exposure of each individual airframe. The only difference is that when a new (to the Pacific) 737 joins the Guam base, it is fitted with a uprated brakes to help with the short runways along the route.

I strapped into 32A and settled in for the medium haul trip to Majuro, announced over the PA as having a flight time of four hours and fifty-five minutes, pretty long for a 737. The announcement went on to apologise that due to the remote oceanic region in which we would be flying, there would be no inflight internet wireless available, but all the seatback entertainment including half a dozen movies would be free. These days I’m more of a fan of using airborne time for reading and contemplation, so the flight map was enough for me.

HONOLULU to MAJURO

As we pushed back right on time at 0725 local, the safety video, with which I would be intimately familiar by sunset, played for the first time, with subtitles in Japanese, Chinese (Mandarin) and Korean. We headed over to 08L past the Aloha Cargo hangar where four 737Fs and an ABX 767-300F were parked, and, aptly, at 0737 we were on our way, blasting out of Honolulu International past Waikiki Beach then banking away on course for Majuro with an initial cruising altitude of 34,000 feet.

The cabin crew, with a long day ahead of them, came down the aisle handing out breakfast baskets containing a tasty hot sausage and scrambled egg muffin, a blueberry yoghurt, a fig bar, and service from the drinks cart. With nothing outside but water for hour after hour, I curled up under the complimentary blanket and got an hour’s sleep to compensate for the early start. When I woke up, we had climbed to our final cruising altitude of 36,000 feet.

I thought back to the 1990s when this exact sector was one of the world’s last bookable flights for anyone hunting a ride on a Douglas DC-8, in the service of Air Marshall Islands.The aircraft, N799AL named Little Amy (derived from AMI – Air Marshall Islands), served with distinction on the route from Honolulu to Majuro as a combi initially with five pallet positions and one hundred passengers, later reconfigured in 1995 for nine pallet positions and fifty-two passengers. The versatile jetliner brought in cars, trucks, mail, building materials and other heavy equipment needed on the islands, and returned to Hawaii with freshly-caught blue fin tuna which was transferred onto Northwest Airlines 747s bound for Japan where the best specimens sold for up to $50,000 for a single fish. Little Amy also flew weekly charters from Honolulu to Kiribati (a.k.a. Christmas Island) serving a similar purpose – essential lifeline of supplies in, seafood exports out. I had made a tentative booking to fly on it, to log a DC-8, but I didn’t have much of a clue about how to get there and the booking was never paid for or flown and a ride on a DC-8 remained elusive as ever. Little Amy went to ATI at the turn of the century with its N799AL registration intact; incredibly, thanks to the initiative of aviation legend Sean Burris at Classic Jet Tours, I got a ride on this exact aircraft in 2011 from McClellan AFB in Sacramento to the DC-8’s birthplace in Long Beach, and back up to McClellan later the same day – two decades later.

The five-hour flight passed quickly and we began our descent into Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, a pair of islands chains (the Sunrise Islands and the Sunset Islands) comprising thirty atolls and no less than 1,152 islands. The national population is 53,000, half of whom live on Majuro, the capital.

Runway 07/25 of Amata Kabua International Airport was nearly as wide as the atoll on which it was situated, a majestic streak of sand, turf and palm trees sneaking around in a wide arc. We landed to the east at 1035 local time, two hours earlier than in Honolulu, but having crossed the International Dateline, it was now a day later, Tuesday. We turned left into the parking area at the far end, barely big enough for our 737; it was amazing to think this had once been home to a DC-8 operator. I noticed that the airport’s two fire engines had come out to meet us, which would happen at each stop; given how short some of the runways were, it was probably not a bad idea.

I planned to disembark at each port; transit passengers were free to do so but had to take hand luggage with them. At the bottom of the boarding ramp was a baggage cart where bags could be dropped off which was helpful, and I went into the terminal, a primitive concrete building containing a snack counter selling drinks and sandwiches, and a table where an islander was selling gifts made of snow-white coral. It was incongrous to see the United Airlines metal sign by the door dividing passengers into two lanes (one for Group 1 Global Services and Group 2 Premier Access; and one for Groups 3-4-5) in such exotic surroundings. We picked up fuel at very port, which surprised me as the logistics of delivery jet fuel to these remote places must be costly, but the runways are too short to allow the extra weight of tankering fuel for more than one flight.

MAJURO to KWAJALEIN

The pilots who brought us from Honolulu were finished work for the day and would continue for the remaining nine hours to Guam as passengers, swapping with a fresh crew who had flown as passengers from Honolulu in seats 1A and 1B. Soon the flight was ready for boarding and I was heading back out across the scorched tarmac for our 737. Passengers took their seats, slightly less of us now. At 1140 we started up and swung around out of the small ramp onto the runway and backtracked before blasting off for a full power departure at 1146 from the 7,897 foot (2,407 metre) strip.

After the long flight from Honolulu, from here on it was all short sectors of an hour or so each; in fact the hop over to Kwajalein, a domestic run within the Marshall Islands, was planned at forty-seven minutes and the cruising altitude was only 28,000 feet.

The destination wasn’t a conventional one, even by Island Hopper standards. “Kwaj” is home to the Ronald Reagan Ballastic Missile Defense Test Site, formerly known as the Kwajalein Missile Range, comprising radar installations, optics, telemetry and communications equipment monitoring 750,000 square miles (1,900,000 square kilometres). The United States Army Garrison Kwajalein Atoll, shortened to USAG-KA, provides accomodation for 2,500 permament residents which includes 1,200 Lockheed-Martin and Bechtel employees and 800 dependents. During our descent, it was announced that due to Kwajalein being a military base, transit passengers would have to stay onboard and photography was strictly forbidden.

We performed another carrier landing with full reverse and energetic braking on runway 05 at Bucholz Army Airfield at 1230 and turned left for parking on the apron, shutting down engines at 1233 alongside a Fairchild Swearingen Metroliner registered N691AX, with another lurking in the shadows inside a hangar. This time there wasn’t even the pretence of a terminal, just squat military buildings scattered around the edge of the ramp and a gate in a chain link fence through which the disembarking military contractors and family members headed into the base. (But was there, somewhere in there, a United Airlines metal sign to weed out the Global Services from the Premier Access, with Groups 3-4-5 to stand aside?)

KWAJALEIN to KOSREI

With the Christmas holidays at an end, I correctly guessed today that disembarking passengers would outnumber those leaving the base, and with a only a handful joining the flight we were half empty but ready to go at 1316 with a planned flight time to Kosrei, our first stop in the Federated States of Micronesia, of an hour and two minutes.

After backtracking, at 1323 we roared down runway 05 and were on our way, climbing to 32,000 feet for enough time that the cabin crew were able to serve drinks to all onboard. As cups and cans were cleared away, engine power was reduced to idle and we were descending once again, with the mountainous island of Kosrei appearing to our left, fringed by a reef all the way round. We performed a wide circuit and landed with another blare of reverse thrust due east onto runway 09 at 1431 and parked at 1436.

Despite the substantial breakfast served on the long oceanic leg from Honolulu to Majuro and the fact that I’d only sat in 32A since then, I was ravenously hungry and once inside the small concrete terminal I was relieved to find a local person selling lunch boxes containing a variety of food items. I had lofty visions of enjoying my lunch in the cruise to Pohnpei but as soon as I was back on board I tore into the tasty selection of battered fish, grilled chicken, rice, spices and vegetables. A member of the crew, who had somewhat adopted me by this point, brought me a cold can of soda water to wash it down with, and by the time the engines were whining back to life at 1515 I was finished eating, tray table back in the vertical position.

KOSREI to POHNPEI

After rolling forward for a few metres, we held our position inside the parking area for over twenty minutes as the flight deck awaited clearance to be issued by Oakland Center, over three thousand miles distant, so it wasn’t until 1538 we finally launched off runway 05 for our planned fifty-five minute hop over to Pohnpei, the capital of Micronesia and the its most populated island, with 34,000 residents. Another drinks service, another one hour time change off the clock, and soon we were descending with the impressive island of Pohnpei appearing off our left side.

As we came in for landing on Pohnpei’s runway 09, the aircraft was caught in a gust of wind and instead of settling, we wavered unsteadily, eating up precious tarmac. The handling pilot had no choice but to take action and slammed us down without ceremony. All of our landings on the islands were carrier landings to some extent but this one hammered home the point – on these short runways, its do-or-die. In fact on March 11, 2001, a Boeing 727-223F of Express One International was written off landing at Pohnpei when it hit the ground short of the runway. The pressure to make landfall within the touchdown zone on these short runways is intense, and contributed to Air Mike’s only crash, which was similar to the Express One incident. The Boeing 727-92C registered N18479 was landing in Yap (no longer part of the Island Hopper proper today, but served by United twice a week on a separate offshoot from Guam twice a week en route to Koror Island) and contacted the ground thirteen feet (four metres) short of the runway threshold, ripping off the right main gear and propelling the aircraft off the side of the runway where large pieces of the wreckage still reside, gradually being reclaimed by nature. Both 727 accidents luckily did not claim lives or cause serious injury but go to show that this kind of flying is not without hazard.

With heavy braking and the aircraft shimmying from side to side, we were quickly down to walking pace, with a few nervous laughs from the passengers. But everyone here knew there was no room to maneouvre, so the atmosphere was free of judgement after what would otherwise be considered a “bad” landing.

I left the aircraft to have a look inside the terminal, every bit as basic as Majuro and Kosrei, if not more so; there seemed to be some kind of restaurant set up behind tinted glass but I was glad I’d already managed to flag down some lunch at Kosrei, because it didn’t look promising.

POHNPEI to CHUUK (TRUK)

As the Island Hopper approached its conclusion, load factor began to rise and when I reboarded, I found myself next to a pair of Americans in suit and tie, unlike most of the passengers who were islanders. Engines started at 1629 and we were off the ground at 1637 for a fifty-nine minute leg across to Chuuk (formerly known as Truk, hence the airport code of TKK). We made another carrier-style landing but this time with smooth touchdown on runway 04 at Chuuk International Airport on the island of Weno, serving a local population of 13,000; the Chuuk population in total numbers around 50,000.

Because we had gradually fallen behind schedule as the day wore on, it was announced that transit passengers would stay onboard, which in some ways was a relief; I wanted to make the most of the day by planting clogs on concrete at each stop, by now I was pretty tired and had a pretty good idea of what to expect of each airport’s rudimentary passenger facilities. Since the number of people onboard during the ground stop was about half that of the actual seating capacity of the aircraft, everyone was asked to move into the D-E-F seats while A-B-C were cleared of rubbish and checked for security, then everyone was asked to move to the A-B-C side while D-E-F were cleared. The process was a little bit awkward because there is only so much room inside a Boeing 737, but it worked and presumably some time was saved by not letting people leave and come back.

CHUUK to GUAM

Passengers boarded until almost every seat was occupied and at 1729 the engines started up once more for the final leg of the Island Hopper (not counting Palau and Manila…) and we were on our way. Because the final leg to Guam was ninety minutes, we had time to get up to 38,000 feet and the crew handed out a surprisingly delicious turkey and cheese sandwich. (All those carrier landings and Space Shuttle launches must work up an appetite because I was hungry again!)

One of the many things about taking this flight was that it illustrated the incredible reliability of the hardware. Gear goes up, gear goes down. Flaps go up, flaps go down. Spoilers, ailerons, elevators. Engines. All of it worked in perfect harmony to steer the jet with perfect precision in a very hostile environment. Boiling hot and humid on the ground, freezing cold and dry as a bone in the cruise. Racing in low over the surf followed by an abrupt deceleration as soon as the wheels touched the ground. The brakes alone must be a work of art.

And the crew’s stamina must surely be tested by this very demanding operation. The cabin crew, even though their numbers are boosted by an extra member, work hard for fourteen hours and oversee five en route stops. For the pilots, the first leg from Honolulu to Majuro is relatively straight forward, but the second duty comprising the next five legs, four of which are into very short fields, must be exhausting even if it is within legal crew duty time. If the pilots felt tired, it didn’t show as we came in after dark for a landing on runway 06L at Guam’s Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport.

After being shoehorned onto short runways all day, whoever was landing at Guam clearly delighted in having so much tarmac to play with – 12,015 feet (3,662 metres), two-and-a-half miles’ worth. A long flare just feet above the ground ended with a smooth touchdown barely perceptible as a rattle through the airframe and we were down for the last time, mission accomplished, at 1855 local time.

A gate change sent us backtracking through the parking area so it was another ten minutes before we were parked at the gate. I wearily gathered up my belongings for the last time and headed for the forward left door, thanking the crew profusely for their hospitality throughout the long day of transpacific flying.

Entry formalities at Guam were the same as at any mainland US airport although on the way from the arrival gate we passed a series of movable dividers, with travellers coralled on the other side. I later learned that because all departing passengers clear security on their way airside, and all arriving passengers clear customs regardless of their origin, the terminal was built with a single airside area (which meant arriving passengers could even buy food or merchandise before entering the customs hall), but post-9/11 security procedures mean arriving and departing passengers must be seperated. (In the early days of the new rules, the seperation was achieved using stacked chairs with security staff as ushers.) The makeshift solutions seemed inkeeping with the rather basic passenger facilities and the overall arrival experience, especially after completing formalities, was more akin to Africa or Latin America in the 80s – the facilities not in a particularly impressive state of repait, information booths unmanned and no officials on duty to assist. Eventually I managed to find a traffic cop to flag down a taxi and I was on my way to the off-brand resort hotel I’d booked cheaply for the night.

I was in bed by 2100 local, partly because I had another early start to catch my United Airlines 777-200 to Tokyo at 0700 the next morning (a non-ER, avgeeks!), and also because I was completely wrecked. That said, I suspect every one of the crew were asleep even before I was. Great work all round United; the Island Hopper not only provides a lifeline to isolated and beautiful tropical islands, it is also an unforgettable aviation experience and if you’re anywhere near the Pacific Ocean on your travels, I hope you can find a way to take this unique flight to paradise.

0 notes