#The Master of the Augsburg Portraits of Painters

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Portrait of a young man, Attributed to The Master of the Augsburg Portraits of Painters

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marie Krøyer (nee Triepcke) - Self-portrait, 1890-91, oil on canvas Marie Triepcke Krøyer Alfvén (1867 – 1940) was a notable Danish painter and furniture designer. Marie had a passion for art at an early age but women at this time had few opportunities for work and training. Marie trained privately in Copenhagen and in 1885, she initiated and cofounded a female art school in Copenhagen. She first exhibited in 1888 at Charlottenborg Castle. In 1889-90 she studied at the Pierre Puvis de Chavannes atelier in Paris alongside fellow Dutch artist, Anna Ancher (nee Brøndum). Their education was influenced by impressionism and naturalism. During her studies, Marie argued for better conditions for female art students.

It was in Paris, Marie formed a relationship with the masterful Norwegian painter, Peder Severin Krøyer. The couple married in Augsburg, 1889 and they settled in the remote fishing town of Skagen, Denmark. The two socialised within an artistic community that later became known as the Skagen Painters. Peder was enchanted by Marie's beauty and she became his favourite model. Marie lacked self-confidence and her work was overshadowed by Pedar's brilliance. She also struggled with depression after the birth of their daughter Vibeke in 1895. Peder also struggled with mental illness and the marriage ended bitterly after just five years. Only Michael and Anna Ancher remained close friends with Marie. Marie remarried with Swedish composer Hugo Alfvén but that relationship also ended in divorce. Marie spent the remainder of her life in Stockholm.

#Marie Krøyer#Marie Triepcke#marie kroyer#self-portrait#portrait#danish painter#skagen painter#impressionism#realism#naturalism#female painter#female artist

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

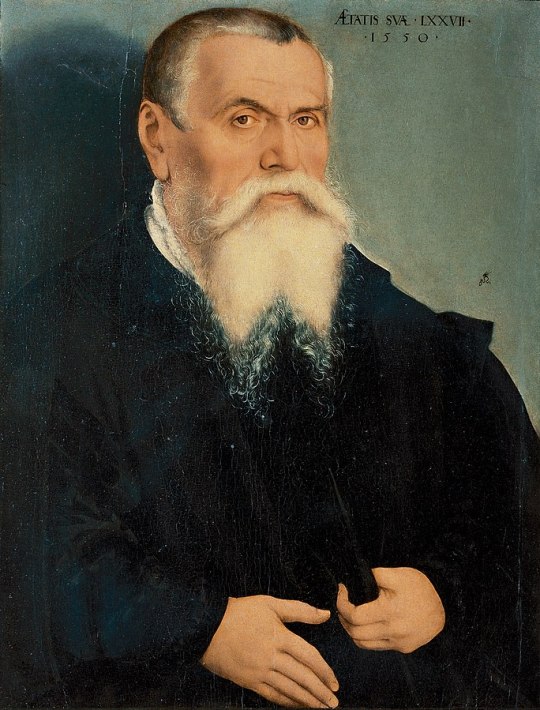

Lucas Cranach the Younger - Portrait of the artist's father, Lucas Cranach the Elder - 1550

Lucas Cranach the Younger (Lucas Cranach der Jüngere; October 4, 1515 – January 25, 1586) was a German Renaissance painter and portraitist, the son of Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (German: Lucas Cranach der Ältere German, c. 1472 – 16 October 1553) was a German Renaissance painter and printmaker in woodcut and engraving. He was court painter to the Electors of Saxony for most of his career, and is known for his portraits, both of German princes and those of the leaders of the Protestant Reformation, whose cause he embraced with enthusiasm. He was a close friend of Martin Luther. Cranach also painted religious subjects, first in the Catholic tradition, and later trying to find new ways of conveying Lutheran religious concerns in art. He continued throughout his career to paint nude subjects drawn from mythology and religion.

Cranach had a large workshop and many of his works exist in different versions; his son Lucas Cranach the Younger and others continued to create versions of his father's works for decades after his death. He has been considered the most successful German artist of his time.

He was born at Kronach in upper Franconia (now central Germany), probably in 1472. His exact date of birth is unknown. He learned the art of drawing from his father Hans Maler (his surname meaning "painter" and denoting his profession, not his ancestry, after the manner of the time and class). His mother, with surname Hübner, died in 1491. Later, the name of his birthplace was used for his surname, another custom of the times. How Cranach was trained is not known, but it was probably with local south German masters, as with his contemporary Matthias Grünewald, who worked at Bamberg and Aschaffenburg (Bamberg is the capital of the diocese in which Kronach lies). There are also suggestions that Cranach spent some time in Vienna around 1500.

From 1504 to 1520 he lived in a house on the south west corner of the marketplace in Wittenberg.

According to Gunderam (the tutor of Cranach's children), Cranach demonstrated his talents as a painter before the close of the 15th century. His work then drew the attention of Duke Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, known as Frederick the Wise, who attached Cranach to his court in 1504. The records of Wittenberg confirm Gunderam's statement to this extent: that Cranach's name appears for the first time in the public accounts on the 24 June 1504, when he drew 50 gulden for the salary of half a year, as pictor ducalis ("the duke's painter"). Cranach was to remain in the service of the Elector and his successors for the rest of his life, although he was able to undertake other work.

Cranach married Barbara Brengbier, the daughter of a burgher of Gotha and also born there; she died at Wittenberg on 26 December 1540. Cranach later owned a house at Gotha, but most likely he got to know Barbara near Wittenberg, where her family also owned a house, which later also belonged to Cranach.

The first evidence of Cranach's skill as an artist comes in a picture dated 1504. Early in his career he was active in several branches of his profession: sometimes a decorative painter, more frequently producing portraits and altarpieces, woodcuts, engravings, and designing the coins for the electorate.

Early in the days of his official employment he startled his master's courtiers by the realism with which he painted still life, game and antlers on the walls of the country palaces at Coburg and Locha; his pictures of deer and wild boar were considered striking, and the duke fostered his passion for this form of art by taking him out to the hunting field, where he sketched "his grace" running the stag, or Duke John sticking a boar.

Before 1508 he had painted several altar-pieces for the Castle Church at Wittenberg in competition with Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair and others; the duke and his brother John were portrayed in various attitudes and a number of his best woodcuts and copper-plates were published.

In 1509 Cranach went to the Netherlands, and painted the Emperor Maximilian and the boy who afterwards became Emperor Charles V. Until 1508 Cranach signed his works with his initials. In that year the elector gave him the winged snake as an emblem, or Kleinod, which superseded the initials on his pictures after that date.

Cranach was the court painter to the electors of Saxony in Wittenberg, an area in the heart of the emerging Protestant faith. His patrons were powerful supporters of Martin Luther, and Cranach used his art as a symbol of the new faith. Cranach made numerous portraits of Luther, and provided woodcut illustrations for Luther's German translation of the Bible. Somewhat later the duke conferred on him the monopoly of the sale of medicines at Wittenberg, and a printer's patent with exclusive privileges as to copyright in Bibles. Cranach's presses were used by Martin Luther. His apothecary shop was open for centuries, and was only lost by fire in 1871.

Cranach, like his patron, was friendly with the Protestant Reformers at a very early stage; yet it is difficult to fix the time of his first meeting with Martin Luther. The oldest reference to Cranach in Luther's correspondence dates from 1520. In a letter written from Worms in 1521, Luther calls him his "gossip", warmly alluding to his "Gevatterin", the artist's wife. Cranach first made an engraving of Luther in 1520, when Luther was an Augustinian friar; five years later, Luther renounced his religious vows, and Cranach was present as a witness at the betrothal festival of Luther and Katharina von Bora. He was also godfather to their first child, Johannes "Hans" Luther, born 1526. In 1530 Luther lived at the citadel of Veste Coburg under the protection of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and his room is preserved there along with a painting of him. The Dukes became noted collectors of Cranach's work, some of which remains in the family collection at Callenberg Castle.

The death in 1525 of the Elector Frederick the Wise and Elector John's in 1532 brought no change in Cranach's position; he remained a favourite with John Frederick I, under whom he twice (1531 and 1540) filled the office of burgomaster of Wittenberg. In 1547, John Frederick was taken prisoner at the Battle of Mühlberg, and Wittenberg was besieged. As Cranach wrote from his house to the grand-master Albert, Duke of Prussia at Königsberg to tell him of John Frederick's capture, he showed his attachment by saying,

I cannot conceal from your Grace that we have been robbed of our dear prince, who from his youth upwards has been a true prince to us, but God will help him out of prison, for the Kaiser is bold enough to revive the Papacy, which God will certainly not allow.

During the siege Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, remembered Cranach from his childhood and summoned him to his camp at Pistritz. Cranach came, and begged on his knees for kind treatment for Elector John Frederick.

Three years afterward, when all the dignitaries of the Empire met at Augsburg to receive commands from the emperor, and Titian came at Charles's bidding to paint King Philip II of Spain, John Frederick asked Cranach to visit the city; and here for a few months he stayed in the household of the captive elector, whom he afterward accompanied home in 1552.

He died at age 81 on October 16, 1553, at Weimar, where the house in which he lived still stands in the marketplace. He was buried in the Jacobsfriedhof in Weimar.

Cranach had two sons, both artists: Hans Cranach, whose life is obscure and who died at Bologna in 1537; and Lucas Cranach the Younger, born in 1515, who died in 1586. He also had three daughters. One of them was Barbara Cranach, who died in 1569, married Christian Brück (Pontanus), and was an ancestor of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

His granddaughter married Polykarp Leyser the Elder, thus making him an ancestor of the Polykarp Leyser family of theologians.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

FRANZ SERAPH LENBACH

On this day of 13th December, Franz Seraph Lenbach, after 1882, Ritter von Lenbach (13 December 1836 – 6 May 1904) was born in South Tyrol, Germany.

He was a painter known for his portraits of prominent personalities. He was often referred to as the "Malerfürst" (Painter Prince).

Lenbach had his primary education at Landsberg, then attended a business school in Landshut, and was apprenticed to the sculptor Anselm Sickinger.

He studied at the Augsburg University of Applied Sciences. While there, he drew and painted in his spare time, befriended Johann Baptist Hofner, the animal painter, and decided to become an artist. He obtained his family's reluctant permission to study at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich, and later took private lessons from Hermann Anschütz.

Lenbach was already an accomplished artist when he became the pupil of Karl von Piloty. In 1858, he staged an exhibition at the Glaspalast and received a scholarship. Works such as A Peasant seeking Shelter from Bad Weather, The Goatherd, and The Arch of Titus was the outcome of his visit to Rome.

In Munich, he took the appointment of professor at the Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School. During this time, he also found an important patron; Baron Adolf Friedrich von Schack. Through his support, he had a guaranteed annual income.

He won a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle and went to Spain, accompanied by his student, Ernst Friedrich von Liphart to make copies of the Old Masters for Schack. His breakthrough came in 1869, when he won a gold medal at the Glaspalast, despite being up against many fashionable French painters.

In 1882, he was awarded the Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown, which entitled him to become "Von Lenbach". In 1885, he was commissioned to do a portrait of Pope Leo XIII. As the Pope did not have time to sit for the portrait, a new technique was used to create a photographic template.

Around 1900, he started to produce trading card designs for the Stollwerck chocolate company of Cologne.

Most of Lenbach's paintings are in the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, Washington, and portraits of Bismarck and Gladstone are in the National Galleries of Scotland and in the Palace of Westminster.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

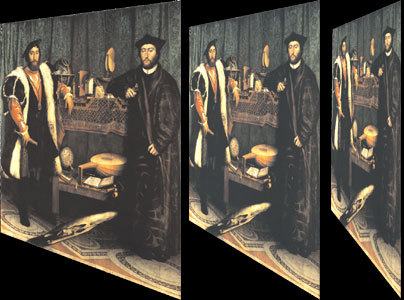

Hans Holbein

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543), one of the most versatile and admired painters of the Northern Renaissance, trained under his father in Augsburg and then worked for leading patrons in Switzerland before settling in England as Court Painter to Henry VIII. To commemorate the five-hundredth anniversary of the artist's birth, Oskar Bätschmann and Pascal Griener offer this richly illustrated book--the first comprehensive monograph on the artist to appear in more than forty years--which is a major advance in our understanding of Holbein's contribution to European art. The authors reexamine every aspect of a remarkable career, and further illuminate the artistic and cultural influences that affected the artist.

Holbein was a hugely ambitious artist, and even during his formative years in Lucerne and Basel, made designs for jewelry, stained glass, and woodcuts, and painted major altarpieces and portraits. He also carried out several monumental decorative schemes for private houses and civic buildings. In his commissions, Holbein sought to rival the greatest masters of Germany and Italy, most notably Dürer and Mantegna, and by the time of his visit to France in 1524 he was determined to secure a position as Court Painter. However, Holbein soon found himself in a precarious situation as a result of the Reformation's increasing hostility toward religious works, and he left for England in 1532. While in England, in addition to decorative schemes and Triumphs, he both drew and painted numerous unrivaled likenesses of leading courtiers, merchants, and diplomats, among which is his celebrated double portrait, The Ambassadors. This book offers both a remarkable range of extant visual evidence and a rewarding and scholarly account of Holbein's oeuvre in its full historical and artistic contexts.

View on Amazon

1 note

·

View note

Photo

David Bailly (1584 – 1657) was a Dutch Golden Age painter.

var quads_screen_width = document.body.clientWidth; if ( quads_screen_width >= 1140 ) { /* desktop monitors */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width >= 1024 && quads_screen_width < 1140 ) { /* tablet landscape */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width >= 768 && quads_screen_width < 1024 ) { /* tablet portrait */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width < 768 ) { /* phone */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }

Bailly was born at Leyden in the Dutch Republic, the son of a Flemish immigrant, calligrapher and fencing master, Peter Bailly. As a draftsman, David was pupil of his father and the copper engraver Jacques de Gheyn.

David Bailly apprenticed with a surgeon-painter Adriaan Verburg in Leiden and then with Cornelius van der Voort, a portrait painter in Amsterdam. According to Houbraken, in the winter of 1608, Bailly took his Grand Tour, travelling to Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Augsburg Hamburg, and via Tirol to Venice, and from there to Rome. On his return he spent five months in Venice, all the while working as a journeyman where he could, before crossing the alps again in 1609. On his return voyage, Bailly worked for several German princes including the Duke of Brunswick. Upon his return to the Netherlands in 1613, Bailly began painting still-life subjects and portraits, including self-portraits and portraits of his students and professors at the University of Leiden. He is known for making a number of vanities paintings depicting transience of this life, with such ephemeral symbols as flowers and candles. In 1648 he became headman of the Leiden Guild of St. Luke. Bailly taught his nephews Harmen and Pieter Steenwijck.

David Bailly was originally published on HiSoUR Art Collection

0 notes

Photo

Hans Holbein

http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=59671

Hans Holbein has claims to be the greatest portrait painter who ever wielded a brush. A central figure in the spread of the Renaissance in northern Europe, whose deftness and pinpoint accuracy captured the spirit and the faces of his age, an artist whose roots were Continental, but he became the father of English painting.

Hans Holbein the Younger was born in Germany in the imperial capital of Augsburg in 1498. He came from an artistic family.

His father, Hans Holbein the Elder, was one of the leading artists of his generation in southern Germany. And his elder brother, Ambrosius, was already showing a precocious talent for drawing.So as soon as the two boys could be made use of, they joined their father's workshop.

But Augsburg was a lot more limited artistically. But further afield, particularly along the Rhine, to the south, things looked a lot more promising.And so in 1515, Hans, together with his elder brother, came here to the city that he effectively put on the European artistic map, Basel.

It was an attractive place for a young artist on the make, a thriving commercial city on the Rhine. It boasted a newly established university and a flourishing collection of printing presses. Books, pamphlets, and title pages all need illustration, which Holbein was eager to supply.

He was quickly accepted into Basel's intellectualcircles, led by the humanist scholar DesideriusErasmus. And it was a version of Erasmus' is InPraise of Folly, which gave the young artist anopportunity to show his skills with thecommission to provide illustrations in the marginof the celebrated satirical text, which analyzedhuman behavior and weakness.

When he was 18, Holbein got his first, illustriousportrait commission to do a picture of the newlyelected mayor of Basel, Jakob Meyer von Hasen,and his wife, Dorothea. Now this is a veryinventive picture. For a start, it's official. He's justbeen elected mayor. But the two figures are dressed relatively informally.

But also, it's a double portrait that has twodistinct images, who are separated and yet they're bound together by the same architecturaldetail in the background and a consistent lightsource that casts a shadow, in here, from theright, that cast shadows on the architecturaldetail, there and there.

So what we have is two figures, who are unifiedbut, at the same time, their own individuality isproclaimed. With Holbein, even from this stage,the detailing is extraordinary. And you look at therings, numerous rings on the mayor's fingers. Itlooks like a knuckle duster to our eyes. Butactually, it's a sign of his own prosperity.

He's a financier. He clutches a coin as a symbol ofthat but also symbolizing the fact that Basel hasjust been given permission to mint coins. He alsopoints towards his wife in a gesture of love.

In a way, it's a rather unglamorous portrait. Thebackground and the detailing is lavish. But thesetwo figures are certainly not made to lookparticularly attractive. It's as if Holbein haspainted them as they are or as they were. ButHolbein's also making his own mark.

And for the first time, he signs his work, hisinitials, HH, and the date, 1560, and a shield or ascroll surrounded by acanthus leaves as if he'sthrowing off the shackles of his apprenticeshipand emerging for the first time as a fully fledgedartist.

And in fact, from this moment on, his career takesoff. He gets a commission from the mayor todecorate the Basel council chamber, which issubsequently destroyed. But from then on in,other portrait commissions also roll in, includingthis one, of Boniface Amerbach, a professor of lawat Basel University.

This was an important commission for Holbein,for not only was Amerbach a close friend ofErasmus, but he became an important collector ofHolbein's works. Here it's clear that his approachwas evolving, a rare, square format, with alandscape adding depth to the image, and thepainting containing an inscribed panelproclaiming its own merits.

It reads, "I may be painted, unreal, but I'm notinferior to life. I am my master's true likeness ashe was at eight times three years."

Holbein's growing confidence stemmed in partfrom his growing acceptance in Basel, where he was made a master of the guild of painters. Hewas also granted citizenship, two years later, afterhis marriage to a local woman, Elsbeth Schmid,with whom we would have four children.

Holbein also began to turn his attention toreligious images, both for public and privatedevotion. This altarpiece, showing eight episodesof Christ's Passion, was begun by Holbein in 1524,some 7 years after an Augustinian monk andscholar, called Martin Luther, nailed his 95 Thesesto the door of the castle church in Wittenberg,railing against the sale of indulgences, or pardonsfrom sin, by the Catholic Church and triggering amovement, which began with the proposedreform of the papacy and ended up splitting theChurch, otherwise known as the ProtestantReformation, whose impact, throughout Europe,was huge.

One of the most eloquent examples of paintinginspired by the ideas of the Reformation, as wellas being one of the most powerful works in theentire history of religious art, is this one, Holbein'simage of the dead Christ, painted 1521.

What he does is a paradox. Because, in a way, he'strying to affirm the idea of the Bible and Christ'slife as a living force, by painting it as graphically aspossible, but through showing an image of Christat his lowest ebb, when he's died and his flesh isbeginning to rot and decay.

There's all sorts of speculation about the fact thatHolbein might have had a body, that he found inthe Rhine, put in his studio and used directly as amodel for this work. But whether that's true ornot, dead bodies were much more in evidence inlate medieval or early modern Europe. And unlikeour world, theirs was not sanitized from the ideaand the image of death.

What we see is something that's very curious and had art historians speculating for the last fewcenturies. Is this a commission? Is it the bottompart of an altarpiece? Well, there's no evidence tosuggest that it is. And in the end, no records provethat the work was commissioned at all.

And what we're left now is the thought that thismay be a personal image of private devotion byHolbein. It's a painting that almost smells as youget close up to is, such is its power as a trigger for the imagination.

Look at the eyes, how the sockets have becomerigid. Rigor mortis is setting in. And what Holbein,I think, is trying to say-- and I think achieves-- isby showing Christ in this putrefied form-- Christ,remember is the word made flesh-- he's alsoemphasizing the miracle of the Resurrection.

He's showing Christ, as no artist has done before,at his lowest ebb. And in a way, it's an affirmationof Holbein's own personal faith. It's also a workwhich establishes him as one of the great talentsof 16th century European painting.

Of all Holbein's patrons in Basel during his earlyyears, by far and away the most important for hissubsequent career was Erasmus, one of the mostcelebrated scholars of the time.

Erasmus' studies in Latin and Greek enabled himto translate the New Testament, which waseventually published in Basel in 1516, where hefirst came into contact with Holbein, whoseintense scrutiny of his subjects seemed to strike achord with the equally thorough scholar, whocommissioned Holbein to produce half a dozen or so portraits of him over the next decade or so.

I love these portraits that Holbein does of Erasmus. They have a detachment in their scrutiny and in their intense observation. But they're also so intimate. And it's as if Holbein, and by extension us, the viewer, has somehow crept into Erasmus' study. And he's peeking over the shoulder of the great scholar as he's wrapped up in his fur-lined cloak to keep the drafts away.

And we're watching as he writes his commentary to St. Mark's gospel, that we can read there. But we've caught him unawares. And in a way, there's a parallel between what the young artist is tryingto do and what his intellectual mentor is doing.

As Erasmus scrawls away, so Holbein has this intense control. And in a way, he's trying to produce some kind of parallel in a visual form to what Erasmus is doing in intellectual and written form.

But the intellectual and religious turmoil in middle Europe had certain negative spin offs for artists, not least because religious commissions were suddenly frowned upon. And in addition,Holbein's portrait business, here in Basel, had allbut dried up.

So he look further afield, starting in 1524, by tripto France, where he tried to get work at the courtof Francis I. But that was unsuccessful. And then,two years later, probably with a recommendationfrom Erasmus himself, he set sail for TudorEngland to try and get work at the court of HenryVIII.

It was during the early part of Henry VIII's reignthat the renaissance was established in England.Architects, craftsmen, sculptors, painters, andpoets were all encouraged to make the journeyacross the Chanel, so that the king and hisministers might harness their talents to proclaimthe power and sophistication of the Tudormonarchy.

It was Erasmus' links with England that providedHolbein with his first introduction to the Englishcourt. Chief amongst Erasmus' friends, and thefirst port of call for Holbein, was Thomas More, afellow scholar and soon to become LordChancellor of England.

More welcomed Holbein to his Chelsea home andcommissioned him to paint a number of portraitsof his household. Most of these no longer survive.But we have this delicate study for an elaboratefamily portrait.

What does survive, however, is one of Holbein'smost direct and precise portraits, that of SirThomas More, himself, painted in 1527. More starsoff into space, a man whose thoughts were on thisworld and the next, wearing the rich gold chain ofa privy counselor.

What really grabs the viewer's attention, though,and perhaps makes the hairs stand up on theback of your neck, are the hairs on More's chinand the extraordinary detail rendered throughhundreds, maybe thousands of tiny brush strokes,which creates an image that seems almostphotographic.

In spite of his success here in England, Holbeinhad to return to Basel in 1528, because he was indanger of losing his citizenship. And over the nextfew years, in both Switzerland and then again,here, in England, he was to witness the fullonslaught of the Reformation and its politicalconsequences.

During Holbein's absence, the Reformation hadbegun to take serious root here in Basel. And theimplications were political as well as religious,with the small Catholic oligarchy beingthreatened by a Protestant democracy.

But things turned ugly at the beginning of 1529,on Shrove Tuesday, when the whole city wassupposed to be celebrating and suddenly anangry mob came up the hill, here, to thecathedral, broke in, tore down statues, smashedstained glass windows, and triggered off a wave oficonoclasm throughout the city.

It's difficult to know what Holbein's religiousviews were at the time. He was born and broughtup a Catholic. And he painted many religiousworks for Catholic patrons and churches. It'salmost certain that many of Holbein's works weredestroyed in the rioting, as very few still survive.

But what he did out of economic necessity andwhat he did from conviction, we'll never fullyknow. There's a clue, though, to his developingreligious inclinations during the turbulent decadeof the '20s in this woodcut, "Christ is the TrueLight," which shows Christ pointing to a candle,which illuminates the entire image and shows theway to the poor and the ordinary on the left,whilst, to the right, the pope and other churchdignitaries follow Plato and Aristotle, thephilosophers of the ancient, classical, paganworld, into the abyss. An image of clear andstrong Protestant sentiment challenging theauthority of the Catholic Church and its arcaneteachings.

During his time back in Basel, Holbein found timeto paint a portrait that wasn't a commission and,in fact, for many, was the most intimate work ofhis life. It shows his wife, Elsbeth, and two of hisfour children, Philipp, who is about six, andKatherina, who is two. In fact, Elsbeth is pregnantwith the third child when this was made.

And it's very curious work, not least because thebackground seems so bleak. It's black. Itenhances the figures. It makes them stand out inrelief. And it also emphasizes the fact that thecomposition mirrors the traditional image of themother and child, or, in fact, Leonardo's image ofSt. Anne, the Madonna, and child.

But in fact, there's something more practical here, or impractical. Because somewhere down theline, after Holbein finished this work-- and he didthe portraits on paper-- they've been cut out andthen mounted on a panel. And so this isn't quitehow they were intended to be seen.

But it's a very, very sad work. His son looks up, I think, more in hope than in expectation. And thedaughter, the young Katherina, doesn't seem toknow the figure that's painting her. But look at theface of the wife. She's red-eyed. Her face looksslightly puffy. And it's almost as if she knows thatHolbein is not going to be around for much longer.

And in fact, he isn't. He can't find work in Basel.And so in the end, in 1532, he goes back toEngland and never returns, leaving the family,effectively, to fend for themselves.

But the England of 1532 was dramaticallydifferent from the country that Holbein had left in1528. In fact, it was on the edge of revolution, withHenry VII in the middle of trying to secure adivorce from Catherine of Aragon.

The divorce scandalized Europe and lead to a splitwith the papacy, with Henry VII proclaiminghimself head of the Church of England. Hobein'spatron, Sir Thomas More, opposed the divorce,resigned, and was eventually executed.

But it doesn't seem to have had a detrimentaleffect on the painter's prospects, because, verysoon, he was moving in the circle surrounding thefuture queen, Ann Boleyn, including More's rivaland later Chancellor of the Exchequer, ThomasCromwell.

Cromwell became the architect of the EnglishReformation, supporting the break with Rome,and cementing it through the dissolution of themonasteries. He was depicted, in both oil paintand, even more tellingly, in this preparatorydrawing by Holbein, as man of ruthless, single-minded ambition.

And in the midst of all these troubles, and directlyconnected to them, Holbein is commissioned topaint what becomes his most celebrated, famous,and complex work, this one "The Ambassadors."Painted in 1533, showing two men, a rareexample, a very early example in European art ofa double, full length portrait.

Jean de Dinteville, he's the ambassador from theFrench court in London. And Georges de Selve,he's the Bishop of Lavaur, who comes overbecause his friend, Jean, is having problemsnegotiating with Henry VIII on behalf of the Kingof France, because Henry is antagonisticallyinvolved in an argument with the pope.

Now, Jean de Dinteville commissions the portrait.And that might explain why he seems to be themost prominent figure. He dominates, certainly interms of surface area. As always with Holbein, thedetails give us a much greater sense of knowledgeof these two men and their world.

For a start, Jean clutches an elaborate daggersheath that has on it his age, 29. Georges leans ona book that gives us his age, 25. And then werealize that, in the center the picture, between thetwo men, is a celebration of the renaissance worldand scholarship that the two of them practice.

So starting at the top, Holbein gives us a celestialglobe of the stars and the heavens and alsorecently invented navigational tools. And thendown below, there's a terrestrial globe, withFrance clearly visible. Then there's an oddtextbook. Next to it is a hymn book, open on thepage of a hymn written by Martin Luther, of allpeople. And then some musical instruments, alute and a collection of flutes.

So what do we make of all this? Well, certainscholars have put forward the view-- and it seemsperfectly credible to me-- that this mathematicalbook is about the process of division. And thatLuther, himself, as well as being a reformer, is alsoa divider of the Church. And that the lute, with isbroken string, is a symbol of frailty, but also itmeans that the hymn can't be fully realized.

And so what is happening here is that there's acomment by Holbein on the religious situation,specifically in England and also, more broadly, inEurope. But I think the key to these paintings arein two details that are not here in the center.

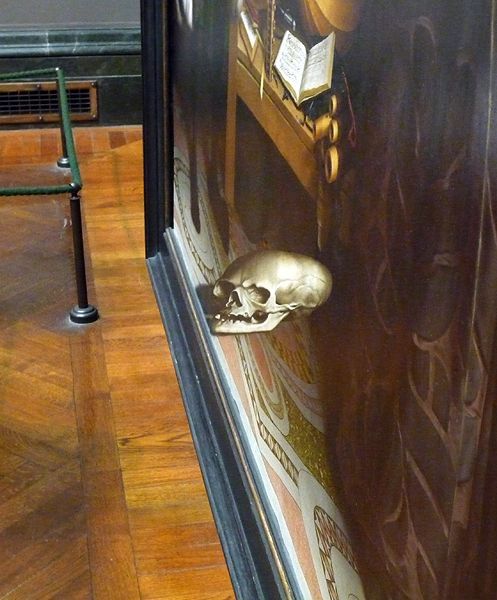

But they're found, first of all, in the top, left-handcorner, which is the crucifix, which is barely inview. But it's making its presence felt. Forsecondly, and much more curious, is this form,here, in the foreground, that you can only seewhen you start to walk and look from anotherperspective. And then you see, clearly, from thisangle, that it's a skull, through a process known asanamorphosis or stretching or distorting theimage.

And it's clear that there's this great symbol, thrustacross the surface of the painting, that it's amemento mori, a reminder of death and thefrailty of human life. And I think the broader pointis being made, by Holbein here, that, in fact,conflict obscures the truth.

The truth is up there, in the top, left-hand cornerof the painting for Holbein. Christ, himself,crucified on the cross, that's the redemptive hopefor mankind. But I think also, Holbein is makingand even more interesting point with this work.And it's to do with the whole process of painting,what Holbein is devoted his life to.

Because no one in European art, up to this point,has scrutinized the natural world as closely asHolbein and rendered it with such extraordinarycare and attention and detail. And what he'smanaging to show us, in this painting, is that youcan have scholarship, you can have diplomacy,you can have an expanded, new culture oflearning. But that you will never grasp the biggerpicture. You will never understand the worldtotally from one, fixed viewpoint. And that youhave to see the world from a number of differentperspectives. And that, I think, is a very profoundpoint.

Within three years of painting "The Ambassadors,"Holbein got the position he really wanted, painterto the king, and began a series of portraits thathave defined how that most familiar of Englishmonarchs has been seen down the ages.

This is the quintessential image of an overbearingand tyrannical monarch. Holbein depicts the Kingseemingly at face value, emphasizing the small,humorless eyes and mouth, the curiously flatcheeks and chin. But his authority is clear,formidable even, amplified by opulent jewelry,depicted in real gold leaf, and helping to create adomineering presence, even though the work,itself, is small.

Consequently, Henry approved of the painting, asdid Thomas Cromwell, who was cleverlyencouraging the use of the painter to promote thepower of the monarch. And idea which wasreinforced when Holbein was commissioned topaint a group portrait of the Tudor dynasty forHenry's Whitehall Palace. The picture,subsequently destroyed in the palace fire of 1698,showed Henry and his now third wife, JaneSeymour, together with his parents, Elizabeth ofYork and Henry VII.

The image of the two Henry's, which survive inthis preparatory drawing, affirms the idea ofdynastic progression and increasing power, fromlean father to vast son. But the Queen JaneSeymour was to die giving birth to Henry's long-awaited heir. But the King didn't spend much timemourning.

Together with the assistance was chancellorCromwell, he decided to try and find a new wife,preferably one who would combine politicaladvantage with the physical beauty that Henrysought. And so Holbein was dispatched to Europeto paint suitable candidates from which Henrycould then make his matrimonial choice.

Holbein's first port of call is to Brussels to paintthis young woman, Christina of Denmark, theDuchess of Milan. Now she's the youngerdaughter of the King of Denmark, who's aLutheran, and who's been deposed. She's alsomarried to the Duke of Milan but is a widow by theage of 12. 4 years later, when she's 16, she's readyto sit for this portrait, because the King of Englandwants to marry her.

Now Holbein gets three hours with her in the datein March. And he sketches her face and her handsand makes intricate studies, which is reflected inthe finished oil. And when Henry sees the results,rumor has it that he falls in love. Certainly, hewants to marry her. He sees, if not a ravishingbeauty, someone who's young and will give himmore heirs, perhaps a healthy heir.

But politically, there are machinations. She's verywell connected. She's also the niece of theEmperor Charles V, who doesn't want anyconnection with Henry VIII. And so the weddingdoesn't take place. Her response, though, is a bitmore diplomatic. She says, if I had two heads, I'dhappily place one at the disposal of the King ofEngland.

Henry finally settled on marrying Anne of Cleves.But Holbein was placed in an impossible position.He was dispatched to the Rhineland, with ordersto produce an instant likeness of Henry's nextintended, but be needed to exercise diplomacyand tact.

Anne's dress seems to have fascinated Holbeinmore than the strangely lifeless symmetry of herfeatures. And Henry's displeasure, at finding Anne of Cleves more, as he put it, like a flat Flander'smare when she arrived for the marriage ceremonyin January, 1540, cost Holbein dear in prestige.

In fact, he received no further significant workfrom Henry. Three years later, having completedhis last portrait, that of himself, Holbein fellseriously ill and died, probably the victim of theplague, which had spread through London 1543.He was 45 years old.

Holbein's influence on British painting isenormous. He made the human individual seemmore real and more exposed than any artistbefore him and is the father of a tradition ofportraiture which continues to this day.

But he also created images of a king and his courtwhich has lived on in the popular imagination,bringing to life one of the most dramatic periodsin English history.

#hans holbein#swedish art#sweden#holbein#ambassadors#holbein's ambassadors#foreshortening#distortion#protestant reformation#swiss art#german artists#swiss artists

0 notes

Photo

Lukas Furtenagel - The painter Hans Burgkmair and his wife Anna, born Allerlai - 1529

Lukas Furtenagel (1505–1546) was a German painter.

Lukas (Laux) Furtenagel was born in Augsburg in 1505 to a family of artists. He began studying art at a young age and was a protégé of painter Hans Burgkmair.

Furtenagel began his apprenticeship in 1515 at the age of 10. After leaving Augsburg, he briefly joined the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder in Wittenberg. Furtenagel was active in Halle from 1542 to 1546. In 1546, he was called to Eisleben to portray Martin Luther after the latter’s death. In the fall of 1546, after returning to Augsburg, Furtenagel was awarded the title of master.

Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473–1531) was a German painter and woodcut printmaker.

Hans Burgkmair was born in Augsburg, the son of painter Thomas Burgkmair. His own son, Hans the Younger, later became a painter as well. From 1488, Burgkmair was a pupil of Martin Schongauer in Colmar. Schongauer died in 1491, before Burgkmair was able to complete the normal period of training. He may have visited Italy at this time, and certainly did so in 1507, which greatly influenced his style. From 1491, he worked in Augsburg, where he became a master and eventually opened his own workshop in 1498.

German art historian Friedrich Wilhelm Hollstein ascribes 834 woodcuts to Burgkmair, the majority of which were intended for book illustrations. Slightly more than a hundred are “single-leaf” prints which were not intended for books. His work shows a talent for striking compositions which blend Italian Renaissance forms with the established German style.

From about 1508, Burgkmair spent much of his time working on the woodcut projects of Maximilian I until the Emperor's death in 1519. He was responsible for nearly half of the 135 prints in the Triumphs of Maximilian, which are large and full of character. He also did most of the illustrations for Weiss Kunig and much of Theurdank. He worked closely with the leading blockcutter Jost de Negker, who became in effect his publisher.

He was an important innovator of the chiaroscuro woodcut, and seems to have been the first to use a tone block, in a print of 1508. His Lovers Surprised by Death (1510) is the first chiaroscuro print to use three blocks, and also the first print that was designed to be printed only in colour, as the line block by itself would not make a satisfactory image. Other chiaroscuro prints from around this date by Baldung and Cranach had line blocks that could be and were printed by themselves. He produced one etching, Venus and Mercury (c1520), etched on a steel plate, but never tried engraving, despite his training with Schongauer.

Burgkmair was also a successful painter, mainly of religious scenes, portraits of Augsburg citizens, and members of the Emperor's court. Many examples of his work are in the galleries of Munich, Vienna and elsewhere.

Burgkmair died at Augsburg in 1531.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lukas Furtenagel - Portrait Sketch of the Dead Martin Luther - 1546

Martin Luther, O.S.A. (10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German professor of theology, composer, priest, Augustinian monk, and a seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation. Luther was ordained to the priesthood in 1507. He came to reject several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church; in particular, he disputed the view on indulgences. Luther proposed an academic discussion of the practice and efficacy of indulgences in his Ninety-five Theses of 1517. His refusal to renounce all of his writings at the demand of Pope Leo X in 1520 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521 resulted in his excommunication by the pope and condemnation as an outlaw by the Holy Roman Emperor.

Luther taught that salvation and, consequently, eternal life are not earned by good deeds but are received only as the free gift of God's grace through the believer's faith in Jesus Christ as redeemer from sin. His theology challenged the authority and office of the Pope by teaching that the Bible is the only source of divinely revealed knowledge, and opposed sacerdotalism by considering all baptized Christians to be a holy priesthood. Those who identify with these, and all of Luther's wider teachings, are called Lutherans, though Luther insisted on Christian or Evangelical (German: evangelisch) as the only acceptable names for individuals who professed Christ.

His translation of the Bible into the German vernacular (instead of Latin) made it more accessible to the laity, an event that had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language, added several principles to the art of translation, and influenced the writing of an English translation, the Tyndale Bible. His hymns influenced the development of singing in Protestant churches. His marriage to Katharina von Bora, a former nun, set a model for the practice of clerical marriage, allowing Protestant clergy to marry.

In two of his later works, Luther expressed antagonistic, violent views towards Jews, and called for the burnings of their synagogues and their deaths. His rhetoric was not directed at Jews alone, but also towards Roman Catholics, Anabaptists, and nontrinitarian Christians. Luther died in 1546 with Pope Leo X's excommunication still effective.

Lukas Furtenagel (1505–1546) was a German painter. Lukas (Laux) Furtenagel was born in Augsburg in 1505 to a family of artists. He began studying art at a young age and was a protégé of painter Hans Burgkmair.

Furtenagel began his apprenticeship in 1515 at the age of 10. After leaving Augsburg, he briefly joined the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder in Wittenberg. Furtenagel was active in Halle from 1542 to 1546. In 1546, he was called to Eisleben to portray Martin Luther after the latter’s death. In the fall of 1546, after returning to Augsburg, Furtenagel was awarded the title of master.

Few of Furtenagel's works survive. One of his most notable is a double portrait of Hans Burgkmair with his wife Anna, ages 56 and 52 respectively. The work, a vanitas, shows the artist and his wife reflected in a hand-mirror as death's heads. The inscription on the mirror reads "Recognize thyself/o death/hope of the world". Prior to the discovery of Furtenagel's signature, the portrait was believed to have been painted by Burgkmair himself. The work is currently held in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

One of Furtenagel's most enduring and popular work is his posthumous portrait of Martin Luther. Upon Luther's death on February 18, 1546, Furtenagel was summoned to Eisleben from Halle. Earlier in the day, an unknown artist from Eisleben depicted Luther on his deathbed. By the time Furtenagel arrived, Luther had already been placed in his coffin. Furtenagel's drawing served as the basis for several reproductions, including Lucas Cranach the Younger's Portrait of Martin Luther on his Death Bed (1546). Furtenagel depicted Luther's body twice, first on the 18th and then again the following day. The surviving drawing is currently held in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Michael Ancher - Portrait af Marie Triepcke, 1889, oil on canvas

Marie Triepcke Krøyer Alfvén (1867 – 1940) was a notable Danish painter and furniture designer. Marie had a passion for art at an early age but women at this time had few opportunities for work and training. Marie training privately in Copenhagen and in 1885, she initiated and cofounded a female art school in Copenhagen. She first exhibited in 1888 at Charlottenborg Castle. In 1889-90 she studied at the Pierre Puvis de Chavannes atelier in Paris alongside fellow Dutch artist, Anna Ancher (nee Brøndum). Their education was influenced by impressionism and naturalism. During her studies, Marie argued for better conditions for female art students.

It was in Paris, Marie formed a relationship with the masterful Norwegian painter, Peder Severin Krøyer. The couple married in Augsburg, 1889 and they settled in the remote fishing town of Skagen, Denmark. The two socialised within an artistic community that later became known as the Skagen Painters. Peder was enchanted by Marie's beauty and she became his favourite model. Marie lacked self-confidence and her work was overshadowed by Pedar's brilliance. She also struggled with depression after the birth of their daughter Vibeke in 1895. Peder also struggled with mental illness and the marriage ended bitterly after just five years. Only Michael and Anna Ancher remained close friends with Marie. Marie remarried with Swedish composer Hugo Alfvén but that relationship also ended in divorce. Marie spent the remainder of her life in Stockholm.

#Michael Ancher#Michael Peter Ancher#Marie Triepcke#1889#1880s#nineteenth century#oil painting#oil on canvas#portrait#skagen#skagen painter#Skagensmalerne#black dress#danish artist#denmark#marie krøyer#danish painter#female artist#female painter

7 notes

·

View notes