#Taymily

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I ask the traffic lights it it'll be alright, they say “💅🏳️🌈🌼”

#just saw this on my way back home from a 4th of July party and took a picture really quick for the joke’s sake#don’t worry I'm not the one driving#taylor swift#gaylor#gaylor swift#lgbetty#friend of dorothea#swiftgron#kaylor#taymily#toë#houghlor#tayliz

655 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Song- Taymily?

I've been going down the Emily Poe rabbit hole, since wondering about the significance of Haunted being played twice on 6/9. I've seen people point out (like Nikki on TikTok) the comparison between Haunted and Breathe with the "Can't breathe whenever you're gone" line, and we basically know Breathe is about Emily.

While diving down this rabbit hole, I discovered Emily's birthday is June 1st- and from what I've seen, there were no Eras shows on this date so it's pretty *close* to her birthday, and maybe a date that's significant to them.

Going further, I found one of the first performances they did together at the Whiskey a Go Go in 2006, the first song to play being "Our Song." While watching, the lyrics really hit me as how queer this song could actually be, particularly:

-The premise of the song is Taylor saying I've listened to ALL kinds of music and NONE of it describes our love, our relationship. I can imagine in 2006, a song about Sapphic love WOULD be difficult to find and so, she wrote one of her own.

-Sneaking around, late at night, quiet on the phone because "your mama don't know" which...yeah, maybe she doesn't know you're...on the phone? I guess? That, or...she doesn't know you're dating a girl.

-The line "Man, I didn't kiss her, and I should have." yada yada, male perspective, we've heard that before.

That was good enough for me, until I saw a post courtesy of throwbackgaylor, informing me that the first surprise song Taylor played for Pride month on the Rep tour- JUNE 1ST, Emily's birthday, was Our Song.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

All Too Well and Good Luck Babe are sister songs

To me, the song All Too Well (10 Minute Version) is so queer, and also a sister song to Good Luck Babe (Chappell Roan).

Disclaimer: Death of the author because the old Taylor is dead anyway, so I can make up whatever I want about this song. Once you put something out into the world, it’s open season for interpretation, and it doesn’t matter if the interpretation is ‘correct’. For the sake of this post, I’m referring to the relationship in All Too Well (10 Minute Version) as sapphic, because that’s how I choose to interpret the song, and it’s not a judgment on Taylor’s actual life. I’m also going to just say All Too Well, but I mean the ten minute version.

The lyric “I was thinking… ‘any day now, he’s gonna call it love’, you never called it what it was” is almost an exact copy of the lyrics “you don’t wanna call it love”, and “you can say that we are nothing but you know the truth”. The speakers’ lovers don’t want to admit that the relationship is love, that it’s serious, because doing so would force them to come to terms with their own sexuality. All Too Well differs from Good Luck Babe in how the speaker thinks about their own sexuality, with the speaker of All Too Well having complex feelings about their sexuality “I reached for you, but all I felt was shame”. The relationship in Good Luck Babe ends because the speaker wanted to be open about their relationship “I just want to love someone who calls me baby”, and in the lyric from All Too Well “maybe I asked for too much, or maybe this thing was a masterpiece before you tore it all up, running scared” it’s possibly implied that the speaker asked to be in the open, and her lover left her instead, because of her fear of coming out.

The relationship in both is also secretive. The speaker in Good Luck Babe longs to be openly dating her lover, and while the speaker of All Too Well seems more okay with being a secret, she still took the relationship much more seriously, “there we are again when nobody had to know, you kept me like a secret, but I kept you like an oath”. In the aftermath of the All Too Well relationship, the speaker knows she can’t publicly address their breakup, so she asks “just between us did the love affair maim you too?”. She wants to know if despite her ex-lover being the one to end it, and claiming the relationship wasn’t love, the relationship still affected her, too.

After both of these relationships end, the speakers’ lovers move on to straight relationships. In the iconic bridge of Good Luck Babe, Chappell sings “When you wake up next to him in the middle of the night, your head in your hands, you’re nothing more than his wife. And when you think about me all those years ago, you’re standing face to face with ‘I told you so’”, and in the chorus, she sings “you’d have to stop the world just to stop the feeling”. Despite her ex-lover’s attempts to forget the relationship and move on to men, she can’t, because what she had with the speaker was real, and her relationships with men were not. A similar sentiment is expressed in All Too Well with the line “back before you lost the one real thing you’ve ever known”; their relationship was real, but the lover in All Too Well preferred the safety of faking her way through straight relationships. Both people in All Too Well would rather forget about the transformative love affair, but they can’t, because “we’d swear to remember it all too well”. “It was rare” because it was a real relationship, a queer relationship, that neither of them had experienced before.

Basically, your honor, it’s gay.

#gaylor#gay#good luck babe#chappell roan#lesbian#queer#queer coded#all too well#all too well 10 min version#all too well ten minute version#red taylor’s version#taylor swift#queer interpretation#text post#tayliz#taymily#interpretation

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

It's not about kaylor but I really want to know about the song all too well. Who is it about? I think Jake G was PR. And the lyrics doesn't fit the Taymily narrative either. This song and the relationship seems very important to her. It hurt her badly. I am asking you because you always make very informative and reliable post that makes sense and closest to the truth.

Also who is Dear John about? Is it really John Mayer? Her only straight relationship I believe in is Joe Jonas.

Hi!

Thank you sooo much for saying that! It means a lot. I really can't claim that my theories are always 1000% right, but I do make a lot of research before posting, and try to cross check everything.

2. I must admit that when you asked the question, I did not have real solid theories or evidence to give you. I was even bending toward telling you that the song might be about Lizz since the timestamp of the song on Spotiy is 5:27 = Lizz birthday.

3. Considering that Taylor wrote this during Speak Now Era and that Lizz was present during that Era, well it doesn't fit the narrative of the song being about a relationship that has ended some time ago. And also, it would have been really weird to write this song during rehearsal where Lizz was present, if it was about her...

But thanks to you! I did a lot of research to try and find evidences (I read all the timelines but I'm not that well verse in what came before Kaylor and Swiftgron).

I asked what my groupchat thought about this.

Re-read the Taymily Masterpost (X)

Read and watched Taymily interviews

And now! I can say with more confidence, that I'm pretty sure this song is about Emily Poe, her fiddle player that worked with her from 2006-2008.

Now. Here's the evidences:

First. As pointed out by my group chat, the song does not seem to fit Tayliz dynamic. It seems to be talking about a complicated relationship with someone older.

As by the lyrics "you said if we were closer in age, maybe it would have been fine"

So first thing I did is look back as to when it was written.

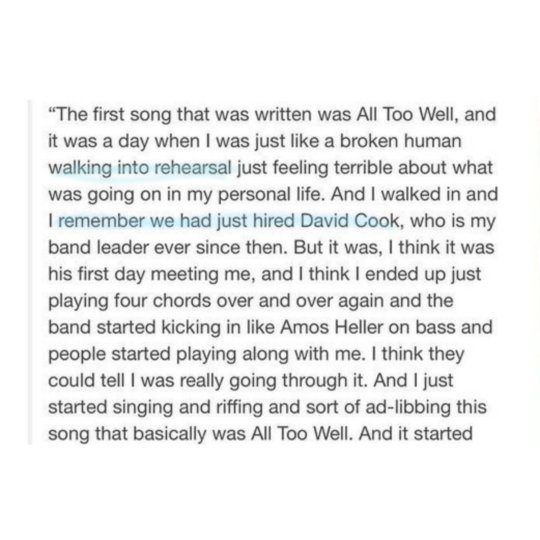

Here's a piece of interview I found:

Thanks to this post: (X)

We know that she wrote it during her reheasal in 2011.

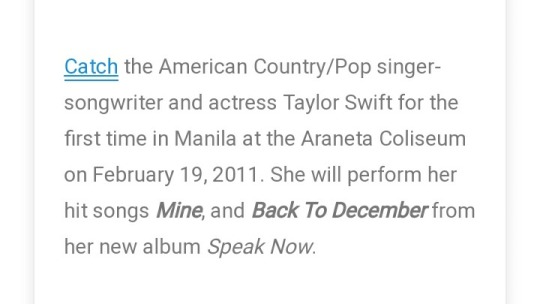

Because here's when David Cook started working with her:

And here's the date of his first show in the Phillipines:

February 2011....

Then, I did a little digging on what was going on with Emily at the time:

And oh does it get interesting!!

Here's an Emily's interview I found (X)

And here's what she was doign in February 2011!!! (I'm excited of the evidence I've found, does it show lol) :

"Two thousand eleven was a big year for me. I became engaged in February, graduated law school in May, took the bar in July, and Eli and I were married in November.”

What did Taylor said?: "I was feeling terrible about what was going on in my personal life"

What if she just learned about Emily's engagement???

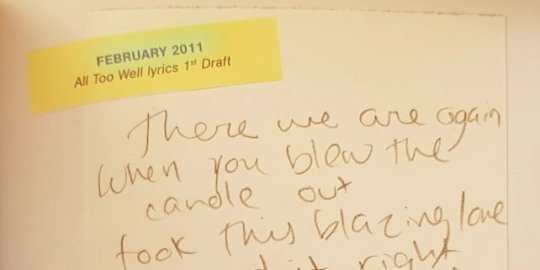

And to make it even more interesting. Here's a journal entry with the first lyrics of All Too Well:

Confirming that it was written in 2011.

This is inchteresting.

But it gets better!

Because, before last year, Emily's Pinterest was public. And on her wedding board, she did save a picture with a red scarf....

It's not Emily, it's just a picture that she had saved in her Pinterest. Thanks to Kate for giving me this!

But what if the red scarf was really just to tie the song to Jake???

Here's another interesting thing I've found in the Taymily timeline:

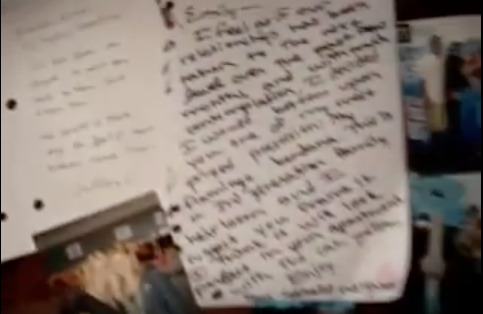

This letter is from the video she made to Emily when she left, with everyone having "I love you Emily" signs.

It says:

“Emily– I feel as if our relationship has been taken to the next level over the past few months and with much contemplation I decided I would bestow upon you one of my most prized possession: my flamingo bandana. This is a 3rd generation family heirloom and i suggest you frame it. I think it will look perfect in your apartment with the cat pillows. Enjoy”

Inchteresting....is the red scarf a bandana??

Also. We know that All Too Well was really significant for Taylor and that for a long time, she was not able to sing it without crying...

So it's about a relationship that had a big impact on her life.

Very recently. Like in June, Taylor performed the song Breathe as a surprise song and very clearly cried during that performance.

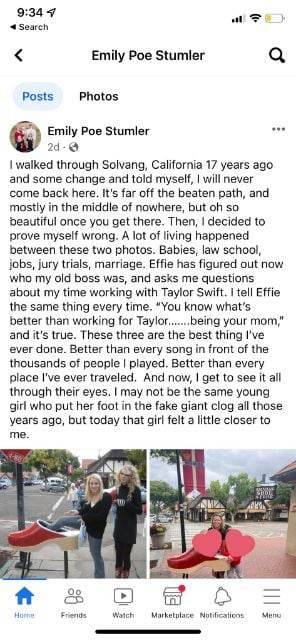

The next day, we learned that the day before the show, Emily did this post on Facebook:

Breathe was heavily rumored to be about Emily back when Fearless came out. But Colbie confirmed it with Fealess Taylor's Version in an interview when she said that it was about something that was going on with one of Taylor's band membre.

So yeah... this would make way more sense being about Emily and having Taylor be emotional singing it for a long time.

Than the song being about a relationship that lasted 3 months.

Of course I can't know for sure for all her relationships...

But most of them I believe was PR. Like the one she had with Jake.

Thanks for the question! It was really interesting doing all those research!

ADDITION!! : It just hit me but! The line "And you call me up again just to break me like a promise"

Fits perfectly with Emily calling her to tell her about the engagement! omg...

SECOND ADDITION: This morning when I woke up, I thought about two things that points to Emily!

1. Taylor turned 21 in 2010, 2 months before writing All Too Well.

"And you call me later and say sorry I didn't make it and I say I'm sorry too" from The Moment I Knew

to two months later:

"And you called me up again just to break me like a promise"

2. The night Taylor sang Breathe and looked devastated after Emily's Facebook post. She also sang All Too Well looking REALLY MAD.

People have all noted it.

Look: (X)

This solidifies even more that All Too Well is about Emily for me...

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

new packs 🪼

#camila cabello#camila cabello icons#girls icons#packs#icons#shawmila#camila cabello headers#camila cabello icons!#twitter icons#taylor swift#twitter packs#taylor swift packs#taylor swift icons#1989 tv#taymily#taylor swift wallpapers

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Emily over here on fiddle. Now Emily has a boyfriend, but she has agreed that what happens in LA stays there. - Taylor Swift

#Gaylor#taylor swift#taylornation#swifties#t swizzle#1989 taylor's version#eras tour#evermore era#t swift#tay tay#taylor swift eras#gaylor swift#friends of dorothea#koincidences#lgbetty#gaylor theory#taymily

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2006, the year Taylor Swift released her first single, a closeted country singer named Chely Wright, then 35, held a 9-millimeter pistol to her mouth. Queer identity was still taboo enough in mainstream America that speaking about her love for another woman would have spelled the end of a country music career. But in suppressing her identity, Ms. Wright had risked her life.

In 2010, she came out to the public, releasing a confessional memoir, “Like Me,” in which she wrote that country music was characterized by culturally enforced closeting, where queer stars would be seen as unworthy of investment unless they lied about their lives. “Country music,” she wrote, “is like the military — don’t ask, don’t tell.”

The culture in which Ms. Wright picked up that gun — the same one in which Ms. Swift first became a star — was stunningly different from today’s. It’s dizzying to think about the strides that have been made in Americans’ acceptance of the L.G.B.T.Q. community over the past decade: marriage equality, queer themes dominating teen entertainment, anti-discrimination laws in housing and, for now, in the workplace. But in recent years, a steady drip of now-out stars — Cara Delevingne, Colton Haynes, Elliot Page, Kristen Stewart, Raven-Symoné and Sam Smith among them — have disclosed that they had been encouraged to suppress their queerness in order to market projects or remain bankable.

The culture of country music hasn’t changed so much that homophobia is gone. Just this past summer, Adam Mac, an openly gay country artist, was shamed out of playing at a festival in his hometown because of his sexual orientation. In September, the singer Maren Morris stepped away from country music; she said she did so in part because of the industry’s lingering anti-queerness. If country music hasn’t changed enough, what’s to say that the larger entertainment industry — and, by extension, our broader culture — has?

Periodically, I return to a video, recorded by a shaky hand more than a decade ago, of Ms. Wright answering questions at a Borders bookstore about her coming out. She likens closeted stardom to a blender, an “insane” and “inhumane” heteronormative machine in which queer artists are chewed to bits.

“It’s going to keep going,” Ms. Wright says, “until someone who has something to lose stands up and just says ‘I’m gay.’ Somebody big.” She continues: “We need our heroes.”

What if someone had already tried, at least once, to change the culture by becoming such a hero? What if, because our culture had yet to come to terms with homophobia, it wasn’t ready for her?

What if that hero’s name was Taylor Alison Swift?

In the world of Taylor Swift, the start of a new “era” means the release of new art (an album and the paratexts — music videos, promotional ephemera, narratives — that supplement it) and a wholesale remaking of the aesthetics that will accompany its promotion, release and memorializing. In recent years, Ms. Swift has dominated pop culture to such a degree that these transformations often end up altering American culture in the process.

In 2019, she was set to release a new album, “Lover,” the first since she left Big Machine Records, her old Nashville-based label, which she has since said limited her creative freedom. The aesthetic of what would be known as the “Lover Era” emerged as rainbows, butterflies and pastel shades of blue, purple and pink, colors that subtly evoke the bisexual pride flag.

On April 26, Lesbian Visibility Day, Ms. Swift released the album’s lead single, “ME!,” in which she sings about self-love and self-acceptance. She co-directed a campy music video to accompany it, which she would later describe as depicting “everything that makes me, me.” It features Ms. Swift dancing at a pride parade, dripping in rainbow paint and turning down a man’s marriage proposal in exchange for a … pussy cat.

At the end of June, the L.G.B.T.Q. community would celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. On June 14, Ms. Swift released the video for her attempt at a pride anthem, “You Need to Calm Down,” in which she and an army of queer celebrities from across generations — the “Queer Eye” hosts, Ellen DeGeneres, Billy Porter, Hayley Kiyoko, to name a few — resist homophobia by living openly. Ms. Swift sings that outrage against queer visibility is a waste of time and energy: “Why are you mad, when you could be GLAAD?”

The video ends with a plea: “Let’s show our pride by demanding that, on a national level, our laws truly treat all of our citizens equally.” Many, in the press and otherwise, saw the video as, at best, a misguided attempt at allyship and, at worst, a straight woman co-opting queer aesthetics and narratives to promote a commercial product.

Then, Ms. Swift performed “Shake It Off” as a surprise for patrons at the Stonewall Inn. Rumors — that were, perhaps, little more than fantasies — swirled in the queerer corners of her fandom, stoked by a suggestive post by the fashion designer Christian Siriano. Would Ms. Swift attend New York City’s WorldPride march on June 30? Would she wear a dress spun from a rainbow? Would she give a speech? If she did, what would she declare about herself?

The Sunday of the march, those fantasies stopped. She announced that the music executive Scooter Braun, who she described as an “incessant, manipulative” bully, had purchased her masters, the lucrative original recordings of her work.

Ms. Swift’s “Lover” was the first record that she created with nearly unchecked creative freedom. Lacking her old label’s constraints, she specifically chose to feature activism for and the aesthetics of the L.G.B.T.Q. community in her confessional, self-expressive art. Even before the sale of her masters, she appeared to be stepping into a new identity — not just an aesthetic — that was distinct from that associated with her past six albums.

When looking back on the artifacts of the months before that album’s release, any close reader of Ms. Swift has a choice. We can consider the album’s aesthetics and activism as performative allyship, as they were largely considered to be at the time. Or we can ask a question, knowing full well that we may never learn the answer: What if the “Lover Era” was merely Ms. Swift’s attempt to douse her work — and herself — in rainbows, as so many baby queers feel compelled to do as they come out to the world?

There’s no way of knowing what could have happened if Ms. Swift’s masters hadn’t been sold. All we know is what happened next. In early August, Ms. Swift posted a rainbow-glazed photo of a series of friendship bracelets, one of which says “PROUD” with beads in the color of the bisexual pride flag. Queer people recognize that this word, deployed this way, typically means that someone is proud of their own identity. But the public did not widely view this as Ms. Swift’s coming out.

Then, Vogue released an interview with Ms. Swift that had been conducted in early June. When discussing her motivations for releasing “You Need to Calm Down,” Ms. Swift said, “Rights are being stripped from basically everyone who isn’t a straight white cisgender male.” She continued: “I didn’t realize until recently that I could advocate for a community that I’m not a part of.” That statement suggests that Ms. Swift did not, in early June, consider herself part of the L.G.B.T.Q. community; it does not illuminate whether that is because she was a straight, cis ally or because she was stuck in the shadowy, solitary recesses of the closet.

On Aug. 22, Ms. Swift publicly committed herself to the as-of-then-unproven project of rerecording and rereleasing her first six albums. The next day, she finally released “Lover,” which raises more questions than it answers. Why does she have to keep secrets just to keep her muse, as all her fans still sing-scream on “Cruel Summer”? About what are the “hundred thrown-out speeches I almost said to you,” in her chronicle of self-doubt, “The Archer,” if not her identity? And what could the album’s closing words, which come at the conclusion of “Daylight,” a song about stepping out of a 20-year darkness and choosing to “let it go,” possibly signal?

I want to be defined by the things that I love,

Not the things I hate,

Not the things that I’m afraid of, I’m afraid of,

Not the things that haunt me in the middle of the night,

I just think that,

You are what you love.

The first time I viewed “Lover” through the prism of queerness, I felt delirious, almost insane. I kept wondering whether what I was perceiving in her work was truly there or if it was merely a mirage, born of earnest projection.

My longtime reading of Ms. Swift’s celebrity — like that of a majority of her fan base — had been stuck in the lingering assumptions left by a period that began more than a decade and a half ago, when a girl with an overexaggerated twang, Shirley Temple curls and Georgia stars in her eyes became famous. Then, she presented as all that was to be expected of a young starlet: attractive yet virginal, knowing yet naïve, not talented enough to be formidable, not commanding enough to be threatening, confessional, eager to please. Her songs earnestly depicted the fantasies of a girl raised in a traditional culture: high school crushes and backwoods drives, princelings and wedding rings, declarations of love that climax only in a kiss — ideally in the pouring rain.

When Ms. Swift was trying to sell albums in that late-2000s media environment, her songwriting didn’t match the image of a sex object, the usual role reserved for female celebrities in our culture. Instead, the story the public told about her was that she laundered her affection to a litter of promising grown men, in exchange for songwriting inspiration. A young Ms. Swift contributed to this narrative by hiding easy-to-decode clues in liner notes that suggested a certain someone was her songs’ inspiration (“SAM SAM SAM SAM SAM SAM,” “ADAM,” “TAY”) or calling out an ex-boyfriend on the “Ellen” show and “Saturday Night Live.” Despite the expansive storytelling in Ms. Swift’s early records, her public image often cast a man’s interest as her greatest ambition.

As Ms. Swift’s career progressed, she began to remake that image: changing her style and presentation, leaving country music for pop and moving from Nashville to New York. By 2019, her celebrity no longer reflected traditional culture; it had instead become a girlboss-y mirror for another dominant culture — that of white, cosmopolitan, neoliberal America.

But in every incarnation, the public has largely seen those songs — especially those for which she doesn’t directly state her inspiration — as cantos about her most recent heterosexual love, whether that idea is substantiated by evidence or not. A large portion of her base still relishes debating what might have happened with the gentleman caller who supposedly inspired her latest album. Feverish discussions of her escapades with the latest yassified London Boy or mustachioed Mr. Americana fuel the tabloid press — and, embarrassingly, much of traditional media — that courts fan engagement by relentlessly, unquestioningly chronicling Ms. Swift’s love life.

Even in 2023, public discussion about the romantic entanglements of Ms. Swift, 34, presumes that the right man will “finally” mean the end of her persistent husbandlessness and childlessness. Whatever you make of Ms. Swift’s extracurricular activities involving a certain football star (romance for the ages? strategic brand partnership? performance art for entertainment’s sake?), the public’s obsession with the relationship has been attention-grabbing, if not lucrative, for all parties, while reinforcing a story that America has long loved to tell about Ms. Swift, and by extension, itself.

Because Ms. Swift hasn’t undeniably subverted our culture’s traditional expectations, she has managed, in an increasingly fractured cultural environment, to simultaneously capture two dominant cultures — traditional and cosmopolitan. To maintain the stranglehold she has on pop culture, Ms. Swift must continue to tell a story that those audiences expect to consume; she falls in love with a man or she gets revenge. As a result, her confessional songs languish in a place of presumed stasis; even as their meaning has grown deeper and their craft more intricate, a substantial portion of her audience’s understanding of them remains wedded to the same old narratives.

But if interpretations of Ms. Swift’s art often languish in stasis, so do the millions upon millions of people who love to play with the dollhouse she has constructed for them. Her dominance in pop culture and the success of her business have given her the rare ability to influence not only her industry but also the worldview of a substantial portion of America. How might her industry, our culture and we, ourselves, change if we made space for Ms. Swift to burn that dollhouse to the ground?

Anyone considering the whole of Ms. Swift’s artistry — the way that her brilliantly calculated celebrity mixes with her soul-baring art — can find discrepancies between the story that underpins her celebrity and the one captured by her songs. One such gap can be found in her “Lover” era. Others appear alongside “dropped hairpins,” or the covert ways someone can signal queer identity to those in the know while leaving others comfortable in their ignorance. Ms. Swift dropped hairpins before “Lover” and has continued to do so since.

Sometimes, Ms. Swift communicates through explicit sartorial choices — hair the colors of the bisexual pride flag or a recurring motif of rainbow dresses. She frequently depicts herself as trapped in glass closets or, well, in regular closets. She drops hairpins on tour as well, paying tribute to the Serpentine Dance of the lesbian artist Loie Fuller during the Reputation Tour or referencing “The Ladder,” one of the earliest lesbian publications in the United States, in her Eras Tour visuals.

Dropped hairpins also appear in Ms. Swift’s songwriting. Sometimes, the description of a muse — the subject of her song, or to whom she sings — seems to fit only a woman, as it does in “It’s Nice to Have a Friend,” “Maroon” or “Hits Different.” Sometimes she suggests a female muse through unfulfilled rhyme schemes, as she does in “The Very First Night,” when she sings “didn’t read the note on the Polaroid picture / they don’t know how much I miss you” (“her,” instead of that pesky little “you,” would rhyme). Her songwriting also noticeably alludes to poets whose muses the historical record incorrectly cast as men — Emily Dickinson chief among them — as if to suggest the same fate awaits her art. Stunningly, she even explicitly refers to dropping hairpins, not once, but twice, on two separate albums.

In isolation, a single dropped hairpin is perhaps meaningless or accidental, but considered together, they’re the unfurling of a ballerina bun after a long performance. Those dropped hairpins began to appear in Ms. Swift’s artistry long before queer identity was undeniably marketable to mainstream America. They suggest to queer people that she is one of us. They also suggest that her art may be far more complex than the eclipsing nature of her celebrity may allow, even now.

Since at least her “Lover” era, Ms. Swift has explicitly encouraged her fans to read into the coded messages (which she calls “Easter eggs”) she leaves in music videos, social media posts and interviews with traditional media outlets, but a majority of those fans largely ignore or discount the dropped hairpins that might hint at queer identity. For them, acknowledging even the possibility that Ms. Swift could be queer would irrevocably alter the way they connect with her celebrity, the true product they’re consuming.

There is such public devotion to the traditional narrative Ms. Swift embodies because American culture enshrines male power. In her sweeping essay, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” the lesbian feminist poet Adrienne Rich identified the way that male power cramps, hinders or devalues women’s creativity. All of the sexist undertones with which Ms. Swift’s work can be discussed (often, even, by fans) flow from compulsory heterosexuality, or the way patriarchy draws power from the presumption that women naturally desire men. She must write about men she surely loves or be unbankable; she must marry and bear children or remain a child herself; she must look like, in her words, a “sexy baby” or be undesirable, “a monster on the hill.”

A woman who loves women is most certainly a monster to a society that prizes male power. She can fulfill none of the functions that a traditional culture imagines — wife, mother, maid, mistress, whore — so she has few places in the historical record. The Sapphic possibility of her work is ignored, censored or lost to time. If there is queerness earnestly implied in Ms. Swift’s work, then it’s no wonder that it, like that of so many other artists before her, is so often rendered invisible in the public imagination.

While Ms. Swift’s songs, largely written from her own perspective, cannot always conform to the idea of a woman our culture expects, her celebrity can. That separation, between Swift the songwriter and Swift the star, allows Ms. Swift to press against the golden birdcage in which she has found herself. She can write about women’s complexity in her confessional songs, but if ever she chooses not to publicly comply with the dominant culture’s fantasy, she will remain uncategorizable, and therefore, unsellable.

Her star — as bright as it is now — would surely dim.

Whether she is conscious of it or not, Ms. Swift signals to queer people — in the language we use to communicate with one another — that she has some affinity for queer identity. There are some queer people who would say that through this sort of signaling, she has already come out, at least to us. But what about coming out in a language the rest of the public will understand?

The difference between any person coming out and a celebrity doing so is the difference between a toy mallet and a sledgehammer. It’s reasonable for celebrities to be reticent; by coming out, they potentially invite death threats, a dogged tabloid press that will track their lovers instead of their beards, the excavation of their past lives, a torrent of public criticism and the implosion of their careers. In a culture of compulsory heterosexuality, to stop lying — by omission or otherwise — is to risk everything.

American culture still expects that stars are cis and straight until they confess themselves guilty. So, when our culture imagines a celebrity’s coming out, it expects an Ellen-style announcement that will submerge the past life in phoenix fire and rebirth the celebrity in a new image. In an ideal culture, wearing a bracelet that says “PROUD,” waving a pride flag onstage, placing a rainbow in album artwork or suggestively answering fan questions on Instagram would be enough. But our current reality expects a supernova.

Because of that expectation, stars end up trapped behind glass, which is reinforced by the tabloid press’s subtle social control. That press shapes the public’s expectations of others’ identities, even when those identities are chasms away from reality. Celebrities who master this press environment — Ms. Swift included — can bolster their business, but in doing so, they reinforce a heteronormative culture that obsesses over pregnancy, women’s bodies and their relationships with men.

That environment is at odds with the American movement for L.G.B.T.Q. equality, which still has fights to win — most pressingly, enshrining trans rights and squashing nonsensical culture wars. But lately I’ve heard many of my young queer contemporaries — and the occasional star — wonder whether the movement has come far enough to dispense with the often messy, often uncomfortable process of coming out, over and over again.

That questioning speaks to an earnest conundrum that queer people confront regularly: Do we live in this world, or the world to which we ought to aspire?

Living in aspiration means ignoring the convention of coming out in favor of just … existing. This is easier for those who can pass as cis and straight if need be, those who are so wealthy or white that the burden of hiding falls to others and those who live in accepting urban enclaves. This is a queer life without friction; coming out in a way straight people can see is no longer a prerequisite for acceptance, fulfillment and equality.

This aspiration is tremendous, but in our current culture, it is available only to a privileged few. Should such an inequality of access to aspiration become the accepted state of affairs, it would leave those who can’t hide to face society’s cruelest actors without the backing of a vocal, activated community. So every queer person who takes issue with the idea that we must come out ought to ask a simple question — what do we owe one another?

If coming out is primarily supposed to be an act of self-actualization, to form our own identities, then we owe one another nothing. This posture recognizes that the act of coming out implicitly reinforces straight and cis identities as default, which is not worth the rewards of outness.

But if coming out is supposed to be a radical act of resistance that seeks to change the way our society imagines people to be, then undeniable visibility is essential to make space for those without power. In this posture, queer people who can live in aspiration owe those who cannot a real world in which our expansive views of love and gender aren’t merely tolerated but celebrated. We have no choice but to actively, vocally press against the world we’re in, until no one is stuck in it.

And so just for a little while longer, we need our heroes.

But if queer people spend all of our time holding out for a guiding light, we might forgo a more pressing question that if answered, just might inch all of us a bit closer to aspiration. The next time heroes appear, are we ready to receive them?

It takes neither a genius nor a radical to see queerness implied by Ms. Swift’s work. But figuring out how to talk about it before the star labels herself is another matter. Right now, those who do so must inject our perceptions with caveats and doubt or pretend we cannot see it (a lie!) — implicitly acquiescing to convention’s constraints in the name of solidarity.

Lying is familiar to queer people; we teach ourselves to do it from an early age, shrouding our identities from others, and ourselves. It’s not without good reason. To maintain the safety (and sometimes the comfort) of the closet, we lie to others, and, most crucially, we allow others to believe lies about us, seeing us as something other than ourselves. Lying is doubly familiar to those of us who are women. To reduce friction, so many of us still shrink life to its barest version in the name of honor or safety, rendering our lives incomplete, our minds lobotomized and our identities unexplored.

By maintaining a culture of lying about what we, uniquely, have the knowledge and experience to see, we commit ourselves to a vow of silence. That vow may protect someone’s safety, but when it is applied to works of culture, it stymies our ability to receive art that has the potential to change or disrupt us. As those with queer identity amass the power of commonplaceness, it’s worth questioning whether the purpose of one of the last great taboos that constrains us befits its cost.

In every case, is the best form of solidarity still silence?

I know that discussing the potential of a star’s queerness before a formal declaration of identity feels, to some, too salacious and gossip-fueled to be worthy of discussion. They might point to the viciousness of the discourse around “queerbaiting” (in which I have participated); to the harm caused by the tabloid press’s dalliances with outing; and, most crucially, to the real material sacrifices that queer stars make to come out, again and again, as reasons to stay silent.

I share many of these reservations. But the stories that dominate our collective imagination shape what our culture permits artists and their audiences to say and be. Every time an artist signals queerness and that transmission falls on deaf ears, that signal dies. Recognizing the possibility of queerness — while being conscious of the difference between possibility and certainty — keeps that signal alive.

So, whatever you make of Ms. Swift’s sexual orientation or gender identity (something that is knowable, perhaps, only to her) or the exact identity of her muses (something better left a mystery), choosing to acknowledge the Sapphic possibility of her work has the potential to cut an audience that is too often constrained by history, expectation and capital loose from the burdens of our culture.

To start, consider what Ms. Swift wrote in the liner notes of her 2017 album, “reputation”: “When this album comes out, gossip blogs will scour the lyrics for the men they can attribute to each song, as if the inspiration for music is as simple and basic as a paternity test.”

Listen to her. At the very least, resist the urge to assume that when Ms. Swift calls the object of her affection “you” in a song, she’s talking about a man with whom she’s been photographed. Just that simple choice opens up a world of Swiftian wordplay. She often plays with pronouns, trading “you” and “him” so that only someone looking for a distinction between two characters might find one. Turns of phrase often contain double or even triple meanings. Her work is a feast laid specifically for the close listener.

Choosing to read closely can also train the mind to resist the image of an unmarried woman that compulsory heterosexuality expects. And even if it is only her audience who points at rainbows, reading Ms. Swift’s work as queer is still worthwhile, for it undermines the assumption that queer identity impedes pop superstardom, paving the way for an out artist to have the success Ms. Swift has.

After all, would it truly be better to wait to talk about any of this for 50, 60, 70 years, until Ms. Swift whispers her life story to a biographer? Or for a century or more, when Ms. Swift’s grandniece donates her diaries to some academic library, for scholars to pore over? To ensure that mea culpas come only when Ms. Swift’s bones have turned to dust and fragments of her songs float away on memory’s summer breeze?

I think not. And so, I must say, as loudly as I can, “I can see you,” even if I risk foolishness for doing so.

I remember the first time I knew I had seen Taylor Alison Swift break free from the trap of stardom. I wasn’t sitting in a crowded stadium in the pouring rain or cuddled up in a movie theater with a bag of popcorn. I was watching a grainy, crackling livestream of the Eras Tour, captured on a fan’s phone.

It’s late at night, the beginning of her acoustic set of surprise songs, this time performed in a yellow dress. She begins playing “Hits Different.” It’s a new song, full of puns, double entendres and wordplay, that toys with the glittering identities in which Ms. Swift indulges.

She’s rushing, as if stopping, even for a second, will cause her to lose her nerve. She stumbles at the bridge, pauses and starts again; the queen of bridges will not mess this up, not tonight.

There it is, at the bridge’s end: “Bet I could still melt your world; argumentative, antithetical dream girl.” An undeniable declaration of love to a woman. As soon as those words leave her lips, she lets out a whoop, pacing around the stage with a grin that cannot be contained.

For a moment, Ms. Swift was out of the woods she had created for herself as a teenager, floating above the trees. The future was within reach; she would, and will, soon take back the rest of her words, her reputation, her name. Maybe the world would see her, maybe it wouldn’t.

But on that stage, she found herself. I was there. Through a fuzzy fancam, I saw it.

And somehow, that was everything.

#nyt x Gaylor swift#Gaylor swift x the msm#mainstream media x gaylor swift#gaylor fandom#Swiftgron#Taymily#tily#the New York Times article

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

taylor swift

Why are all your poems about girls. Are you trying to write from a boys point of view? I think that's really creative and I've never seen that in writing before! You're going to go far with your poetry :)

I’M A HUGE LESBIAN

#taylor swift#gaylor swift#lgbetty#gaylor#swiftgron#karlie kloss#kaylor#lgbtq#sapphic#lesbian#bisexual#taymily

138K notes

·

View notes

Text

My Gaylor Journey: A Year Later 🌈

So, I posted about my Gaylor opinions a year ago today, my first (intentional) post about Gaylor after properly looking into the community for the first time and eventually joining it. I can't believe it's been that long, Jesus! Feels both too long and yet too short of a time. Well, I want to commemorate that; hopefully, I'll make sense, as there's so much I feel and want to say. I don't think I'll ever truly get it all out of me. But here:

I've enjoyed my time here so much! This period has been surprisingly influential for me. For one thing, I've gained some lovely mutuals! I've never had so many before, so it's new, but I enjoy you all. You guys are so kind, smart, and welcoming!

I've also learned so much about queerness, the queer experience, and queer history that I just never would've known before. And I was already very into queer history before. I adore how I listen to Taylor's music now. "Wrong" interpretation or not, looking at her music from a queer lens is so interesting and so easy. I had looked at it from a queer perspective before, but it was more through my eyes. How could this song relate to me and my queerness? Never in regards to the possibility of Taylor's. It's crazy to remember being younger, listening to her music, and getting queer vibes, but assuming I was projecting. Nice to know I was never alone in my thoughts. Looking at the potential real muses is fun, but just daring to look at things another way has been fulfilling alone. I had no clue I could get more connected with Taylor's work, but somehow this community has proven me wrong.

Being here has also saved me from a lot of worrying probably. The Swiftie community since Joe ended whatever he had with Taylor has been very much so changed since I discovered it in 2018, so while I have nothing against nice Swifties, I'm glad I mostly stick to the Gaylor side of things these days. This fandom's less crowded and I like experiencing Tay's art this way. Being a fan shouldn't feel so crazy. Not too long ago, I was having a conversation with one of my college mentors, who's a Swiftie, the day after TTPD was announced, I believe. We were both excited and I spouted out several watered-down versions of Gaylor theories (can never be too careful who you Gaylor in front of), cutting out the gay parts, and what I thought they meant for what TTPD was expected to be; theories like the burning lover house symbolizing "a new phase of her career" starting with TTPD, or white symbolizing rebirth, blah, blah, you know. And absolutely no offense to my mentor, she's lovely, but I was a bit gobsmacked when her theories only had to do with Joe. It was so... bare-bones. Dry. Boring. Don't you wonder what this means for Taylor herself, not just some boy she may or may not be dunking on? She also had so much seemingly incorrect info about the Toe narrative, saying Joe has a music career (he doesn't???) and that Taylor herself confirmed, word of mouth, that she cheated on Joe, which definitely would not be very characteristically "cryptic and Machiavellian" of her to just confirm like that. Just saying it would not be how she tells us a detail like that. I didn't realize people truly thought she cheated till that conversation. They were just very hard to believe things, whether or not you believe in Gaylor or mainstream narratives. She said a lot of her theories came from TikTok, so misinformation isn't shocking in the slightest; people rarely give good sources over there, so if you find someone who does they seem to be a needle in a haystack, sadly. But that conversation reminded me just how much things have changed, both in me and the fandom. Having fresh relationship drama for the first time in 6 years made some Swifties feral and I'm glad I'm not in it. Getting swept up in that shit is easy and I fear I could've if it weren't for jumping ship in time. As Taylor's signaling gets louder and louder again, possibly gearing up for another coming-out attempt, I think I joined just in time. The goddess of timing found me beguiling, I guess.

It just makes me sad that for these types of fans, Taylor's music and craft aren't about her anymore, but about the guys. It's so weird to see fans introduce new Swifties by going over all the supposed muses instead of talking about her and how this song or album communicates her emotions about a situation. They are deeply missing out. Even when I was only in the general fandom, despite my jokes about the boys, I ultimately thought Taylor was the most important factor in her songs. And it seemed like others thought that too, until all this new Joe-Travis-drama eclipsed that. Or till some bad new fans came in just for the drama and to hop on the more trendy version of "loving" her that's going on now. Or maybe I was in my own bubble and it's always been like this. She was never simply "Mrs. Alwyn" and she's not "Mrs. Kelce" or even "Mrs. Kloss" and it's strange to see her get called that as if she's not TAYLOR FUCKING SWIFT. That's not enough? Maybe I'm taking it too seriously or literally, but it feels so wrong to boil her down to just that. I get where it comes from, Taylor's music appeals to the hopeless romantics such as myself, but there's more to Taylor, us, and life than just romance and being someone's "spouse".

Many Swifties rightfully criticize the media for only focusing on Taylor's alleged love life, but some of them hypocritically do the exact same thing, only I'd argue it's worse because they seem to think they're entitled to do so because they're fans or feel like her friends. We don't know Taylor. I don't know Taylor. If she's openly talking about her album(s)/re-record(s) and the craft behind creating it, or her emotional journey creating it, maybe don't yell out to her face about some trivial thing connecting to whoever you think the muse is (looking at you TIFF 2022—I'll never be over that). I'm glad Taylor seems to recognize this behavior and has at least tried to remind fans of the distance between herself and them in recent years; I mean, compare the songs she wrote for fans years ago like "Long Live" and "The Archer" vs "Dear Reader" and potentially "You're Losing me" and "But Daddy I Love Him" if you interpret them that way. They're all wonderful, but more recent songs remind us that she's a stranger to us as opposed to just talking about how grateful she is for us (which I'm sure she still is). I've mentioned in the past that I think this is part of why the TV eras beyond the Red TV era and promo for TTPD have been so laid back in comparison; she doesn't want fans getting way too into "defending" her from [insert "ex-boyfriend" here] like they did during Red TV's release, so she's making it less "exciting". 1989 TV didn't even get music videos. She's never dignified invasive questions with a response to interviewers, so why would she for some fan(s)? You aren't any more special or any less of a stranger to her than those interviewers were. None of us are, including Gaylors (that's why we can't out her, strangers can't out strangers with only pure speculation).

I find it interesting to see how differently the two sides of this fandom treat the potential ex-muses of songs. In the general fandom, there's a lot of animosity, where swifties love to joke about hating or destroying whomever (and I'm chill with jokes), but sometimes it goes way too far. Many Swifties hate most potential exes, exceptions being people like Harry Styles or Taylor Lautner because they have their own fandoms that tend to overlap with Taylor's. But Gaylors rarely do the exact same with exes. Potential exes aren't brought up unless necessary and I've never seen anyone even jokingly hate anyone purely because they are an ex and therefore bad; it might be around, but the fact that I can't find it nearly as easily is something. We'll hold ex-muses (and Taylor) accountable for potential mishaps in past relationships and that's it. Say what you will about Gaylors, but I've never heard of any Gaylors sending someone like Dianna Agron death threats like some Swifties have done with John Mayer.

One huge thing I was not expecting when joining this fandom was becoming slightly disillusioned by the Swiftie title. Don't get me wrong, I'm fine with being called that, as I know that's what I am ultimately and it's not terrible to be a Swiftie inherently by any means. But being opened up to the deep homophobia, bullying, and even doxxing in the Hetlor community has really made me feel odd lumping myself in with "Swifties", as they still call themselves, at times. I don't know how I never stumbled across it when in the general fandom, at least not that I can recall (I feel like I would if I did). From what I gather, Swifties have a rep for being a pretty sweet fandom, and many people are, but I can't help but feel sour about it sometimes after seeing what I've seen from some Swifties. I hope one day the homophobia and just basic vitriol with these types of fans can be lightened up by a cultural shift or something. Way too many people are unaware of the layers of the conversation about outing, closeting, speculation, etc. I myself wasn't before entering the Gaylor fandom and I'm glad I am now. I knew lots of history, but didn't properly apply it to how we can see things now. It's very odd, almost embarrassing, looking at some of my old Swiftie posts now, especially ones about Joe and Gaylors, because I don't feel that way anymore. I was never hateful, but I had some wrong ideas. I guess I'll keep them up though, in order to be honest with myself and anyone who wants to maybe dig into my blog. Plus there's not actually anything to be too embarrassed about from what I remember, it's just a very "in my head" type of thing. I'm glad I'm not as emotionally invested in Taylor's supposed exes anymore. Even when it comes to Karlie as an LSK, I'd be fine if Kaylor was broken up or never together. Surprised and maybe a little sad, but I expect to be okay if that were to be a revelation. It feels much healthier.

I even suspect that being here has helped me with accepting my own queerness further, and I thought I had fully done that already. I guess internal acceptance is a forever journey, at least for me. I came out to my grandparents mid last year and early this year, something I was planning on delaying till I went away to college (I'm doing college virtually for now). I think this community helped me.

I deeply wish that both sides of Taylor's fandom could come together, hear each other, and co-exist. I hate that Gaylors are so vilified for simply suggesting a random lady might be queer as if seeing potential hints of queerness in other people and pondering their sexuality hasn't always existed in queer culture and continues to prevail. We still see primarily femme sapphics ask how they can signal that they're queer without saying so, much like what Taylor might be doing with her hairpins and games. Why is it wrong to be on the other end of that interaction, seeing and acknowledging the signals? In my personal opinion, I think it's at least a bit homophobic in and of itself to say that queer people must come out in a loud, upfront, obvious-to-straights way in order to be seen as queer, otherwise they are forcibly slated as the default of straight. Yes, some people have a boundary about speculation, and that should 100% be respected for those folks, but Taylor specifically has set no such boundary as of me typing this out. Why still force her into the straight box when she's never plainly said she's straight, always toeing the line no pun intended, not giving any clear answers for now, which she doesn't owe. Honestly, I feel like it's more likely that if she were straight she would have such an issue saying plainly; straight people don't coyly tiptoe around saying they're straight like that, but that's just my perspective. When the discourse around speculation is brought up, I often see people say something along the lines of, "Well, I wouldn't want someone to speculate on me," and that's completely fine to feel, but that's your boundary. Not everyone feels that way. Some want to be seen without a definitive word out of their mouth beforehand. This is coming from someone who, when offline, sometimes gets a bit internally antsy when people inform me they could tell my lesbian-ness with or without me intending to signal, though not offended. Yet I also sometimes hate to tell people in verbal words. It can be exhausting, not in just a scary way, but in the sense that it can be akin to explaining that you breathe; being queer just comes so naturally for me because it is natural, so explaining gets tiresome, especially since straights never have to. For me, and in general, speculation is not as black and white as "you should never do it" or "you should always do it". You shouldn't cross people's boundaries, but you shouldn't assume people's boundaries either; that can be just as wrong and dangerous.

Gaylors and Swifties are the same fandom, so why can't we act like it, even when we disagree?

Everyone and everything I've involved myself in here has been so enriching and even if all the Gaylor theories were somehow proven wrong, I wouldn't regret my time here. It's meant too much to me. I'm very grateful and excited to see how this progresses for me. I can't find enough words to express it.

To any rude Hetlors out there, I hope you find it in your heart to treat others with kindness instead of throwing shade at those you simply don't understand/agree with. If you're going to hurt others, I don't want anything to do with you. Kindly leave for both our peace of mind.

To the vast majority of you who have been wonderful, welcoming, and kind, especially the ones who were here before I entered the Gaylor fandom, and didn't leave after, I love you all. You can stay. ♥

🩷❤️🧡💛💚🩵💙💜

#gaylor#gaylors#gaylor swift#lgbetty#friends of dorothea#friend of dorothea#swiftgron#dianna agron#taymily#toë#houghlor#tayliz#kaylor#late stage kaylor#lsk

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching the TikTokers and Redditors discover that Taylor has had alleged wlw relationships before Karlie will never not be amusing.

#if taylor ever wants to come out and say that meeting karlie was when she realized she was gay#i think most people will believe it#these newbies seem to be completely unaware of taymily tayliz and the julianne hough rumors#swiftgron is a little more well known but not by a large margin#most the casuals and the newbs connect gaylor to kaylor specifically

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

i thought the song was about emily poe

i think this is the consensus

yes yes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

And now with the song Paris in existence, I feel like this theory's take on Paris is even more convincing. She meets her Lover on the low, "taken by the view like we were in Paris". They aren't actually in Paris, they are in an unnamed private place, "privacy sign on the door and on my page and on the whole world". Paris is a red herring for where they really are, a place they can hide.

My love was as cruel as the cities I lived in

This lyric really stuck out to me as an important one. Kind of feels like it’s getting ignored so I wanted to get into the weeds on it.

I believe this lyric is in direct reference to Taylor being closeted. And CITIES themselves are a very important theme on Lover.

It seems that cities are meant to be symbolic of certain people in Taylor’s story (further evidence of this: “I’m New York City” // “You’re the West Village”).

So if we go by that logic, we’ve got:

Nashville = Emily, Taylor’s first love; a cruel love because they had to break up so Taylor could pursue greater fame. Taylor and Emily were together while Taylor was still very much a country artist based in Nashville. Emily was her fiddle player; a fact that is eerily symbolic on its own as pop Taylor no longer needs a fiddle player.

Los Angeles = Dianna, Taylor’s first experience with deep passion and infatuation; a cruel love because Dianna was commitment-phobic while Taylor wanted a real, lasting relationship and both were heavily closeted. It’s well established that Dianna and Taylor lived close by one another in LA, and this is why so many of Tay’s lyrics reference an ex driving by.

NYC: Karlie, Taylor’s true love

London: symbolizes the beards (who have as of late all been British)

Okay let’s keep going. What cities has Taylor lived in since she’s been in the spotlight?

Nashville, LA and New York.

Funny enough, she also spends a lot of time in London... WORKING. (Also important: it’s almost as though Taylor and her team go out of their way to remind us again and again that Taylor hasn’t bought a place in London; she rents.)

So what makes Nashville cruel? Homophobia.

It’s no secret (just ask Chely Wright) that young country artists are closeted to appeal to more conservative listeners. Taylor’s been laying hints that Scott Borchetta and BMR may have had a big hand in her closeting as a young artist. And her music has insinuated that this is what broke her and Emily up.

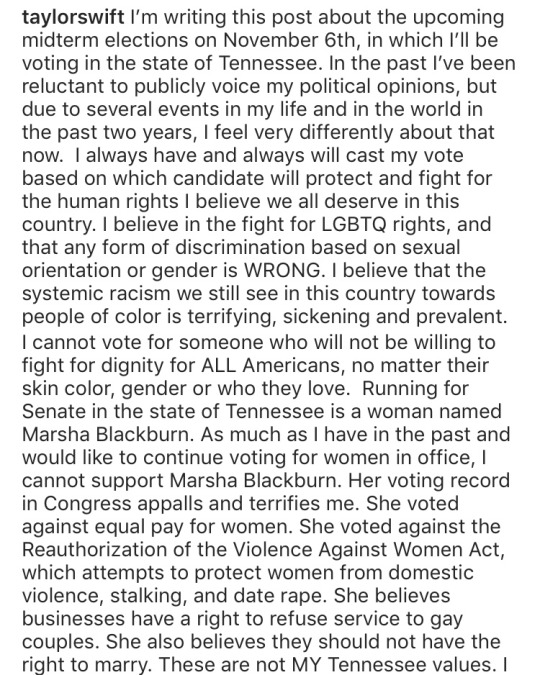

Further, Taylor actually pointed out Tennessee’s homophobia recently with her political post last November explaining why Marsha Blackburn shouldn’t be elected. Look at what she says:

Yes, Taylor wants us to vote. But she also wants us to know that she’s calling out Blackburn specifically for her homophobia. Taylor doesn’t want to accept living in a state that would treat her like a lesser human being, and whose politicians would legislate away her rights. Cruel, indeed.

Further evidence for this: I believe Taylor mentioning the 16th avenue reference in ITHK being about music row in Nashville was supposed to make us draw this connection. She flat out says the choice wasn’t random; AKA pay attention Swifties!

So where does Nashville fit into this world Taylor has created? What does she want us to know about Nashville? It’s where she got her start. It’s where she’s done the BUSINESS of songwriting. It’s her roots, but it’s a cruel place to have established herself, when it’s still not accepting of her true self.

Okay, so what makes LA cruel? A different, subtler form of homophobia.

LA may come across as an accepting town, but young stars are still very much expected to be closeted to appeal to a wider fan base.

“Everyone looked worse in the light” may be referencing the smoke and mirrors of living in LA. The same person might tell you they accept gay people but then advise you to remain closeted to advance your career.

It’s kind of a mindfuck of a place to be, where everything is based off of image and so many people are trying to use you for your fame and connections.

Meanwhile, we KNOW New York is different from these cruel cities because Taylor makes it clear throughout Lover—and all her music since 1989—that New York stands alone in contrast to the other places she’s lived as a city associated with LOVE and her lover.

Although Taylor’s relationship with Karlie may have been cruel initially (cruel summer) their love has blossomed into a cityscape as vast as the Big Apple itself.

Taylor loves NYC so much she can’t stop writing about it.

And what’s one major way she contrasts New York to the other cities??

And you can want who you want // boys and boys and girls and girls

New York is a town that doesn’t care about your identity. It’s a town where you can disappear into the crowd and be anyone. It’s a town of possibilities. And I can see how that would have been so beautiful to a young Taylor. The idea that she could just be herself (albeit with some self-protective measures in place).

New York represents so much to Taylor. Freedom, self-expression, connection, community and of course her true love with Karlie.

Another cool tidbit to go with this theory: Taylor has hinted that her current lover has also been part of these “cruel cities” for her as she’s grown up (“got my heartbeat // skipping down 16th Avenue” and “sunset and vine // you’ve ruined my life by not being mine”) so perhaps this speaks to her healing from the hurts of the past. Daylight the song seems to speak to this healing. Taylor’s been through it, but she’s come out the other side into the daylight with a love that’s really something; not just the idea of something.

One last note on this: Interestingly, although Taylor has used Paris—the city of love—for a lot of her promo and imagery in this era, she never once mentions it in her music. In contrast, she’s made direct references to Nash, NYC, LA and London in her songs. Part of me thinks Paris may be a red herring, or perhaps somewhere she meets up with her lover on the low. Maybe she is using “the city of love” to get us to pay attention to the cities that actually surface in her story and what they mean.

Remember: Taylor told us in Rolling Stone that her music is the truth about her life; the rest is marketing.

Thank you for coming to my TED talk.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some quick thoughts on SNTV:

“I Can See You” is Tayliz

“Electric Touch” is either Tayliz v Taymily (requited v unrequited) or Swiftgron v Tayliz (more likely the first option considering the clear references to “Breathe”)

“When Emma Falls In Love”, “Foolish One”, and “Enchanted” could be about her unrequited crush on Emma S.

I’m very happy that she brought Liz (and Caitlin) back for this one, but I expected she would since she had already brought her back for Red TV. I still wish we could get an actual feature, though (“Better Man” was so close), their voices sound amazing together (maybe even more so now than they did when Liz was in the band).

I do not believe in late stage anything, including Tayliz. I think the rerecording process (which probably began to some extent before the pandemic in 2020) had her reflecting a lot on the past and previous relationships/situationships. That’s why there seems to be a lot of reminiscing about and references to older songs and past relationships on folklore, evermore, and Midnights.

I haven’t felt like posting as much about Tayliz, hence why this blog has become essentially inactive, because I noticed Liz seemed like the type who would manage to stumble across the theories (not this blog in particular, just all the Twitter and TikTok stuff) and I didn’t feel like adding much more to that discussion. And, in fact, I deleted and archived some of my previous posts for that reason.

I have seen tweets the last couple days about Liz watching Tayliz stuff, so I’m not super comfortable with that (that’s just a personal thing, not an admonishing or strong judgment on anyone who feels comfortable doing so). I’ll stick to my once in a blue moon tumblr posts, where I actively avoid using last names haha.

I do think they may have had something in the past and that Taylor has possibly written songs about her and vice versa, but neither one of them have made a clear statement on their sexuality and Liz seems to be currently dating one of her longtime close friends.

I think Taylor and Liz, for whatever reason, had a little bit of a falling out around fall 2012, but are on good terms now and likely have been for many years. Liz is one Taylor’s oldest friends at this point and she (and Caitlin) was there to see first hand the transition from playing small shows in bars to selling out arenas. She’s one of her few “industry” friends who knew her and admired/supported her before she blew up, so I do hope they are at least friends at this point.

I still think Tayliz is way more likely Taylor/Martin or any of the alleged public boyfriends, slightly less likely than Taylianne, and moderately less likely than Swiftgron and Kaylor.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m like 90% convinced that they had a situationship, and at the bare minimum had a very strong romantic friendship, it’s just that I am always skeptical about everything, so unless one of them confirms it, I can’t be fully on board. At this moment, I do believe they had a situationship and that both have written multiple songs about the other and have referenced each other in music videos. I am not convinced that they ever had any kind of defined, serious, committed relationship. I definitely find Tayliz far more convincing than any of the men we are meant to believe Taylor has been attracted to.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

she said it was about meeting a new person after having a situation with a past partner have gossip and talking pull them apart" -but the timeline just doesn't fit with Karlie🤷 i think the past partner was Emily or Liz. I'm not into Taymily but Emily was fired after people found out her and Taylor having relationship and that why the secret message in Breathe was "I'm sorry I'm sorry I'm sorry". IKP is pretty gay song after Emily she was in relationship with men i guess Dianna was her second serious wlw relationship.

the timeline ONLY fits with karlie given the song was conceptualized in late 2013 or late 2014.

"but Emily was fired after people found out her and Taylor having relationship"

this is patently FALSE. a source close to taylor contacted the podcast be there in 5 and spilled and taylor and emily were NEVER involved like that and emily was fired for reasons that had nothing to do with that.

i need you to chill ok

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, so new context with the release of “the Anthology.”

The Tortured Poets Department felt like its own new era—and it is, in a way. But not in the way we’ve been led to expect for years.

It’s just…a very LONG album with a distinct array of tones. We see a general tonal shift halfway through, and refocus on acoustic instrumentation. It’s like, very Jack+Taylor Synthpop bait and switch with Taylor+Aaron Acoustic lying in wait for us. And I’m still processing that and whatever implications exist there.

But what I notice is that there are a LOT of songs. And these songs feel different even if many seem similar. I get vibes from different assumed events. And that’s why I think…

TTPD:TA is a recap and closure of a previous life.

We literally hear “eras fading into grey,” which mentions the visual contrast between this album’s aesthetic and the current tour, and also hints at an end of eras.

Throughout this album, we get the expected references to publicly documented romantic excursions and drama, but we also get introspective tracks. This album is the one where she seems most tired of public perception. Of being perceived and picked apart.

And hints of the sacrifices made and regrets resulting from her climb to success.

This is an album steeped in regret, and anger, and exhaustion, set amongst handfuls of sparkling gems from each era tossed into the salad to provide contrast.

Taylor is playing with the words “greige” and “grey” a lot…mostly in how it’s coming after an explosion of color. It’s a very “goodbye rainbow” vibe.

Then there’s the prologue. “My muses, collected like bruises.” Multiple muses are referenced—whether that’s the Het side or the Gaylor side, it makes no difference; the amount is still there. She presenting them as evidence, showing us these files.

Something is coming, and something is leaving.

She’s telling us how depressed she is, how much regret and bitterness fills her. She’s getting fed up—in a way more profound than even Reputation presented.

We’re getting glimpses of stories about muses we may have heard or considered before, and ones that have evaded us. Songs that sound very like they belong in 1989 or Red in their themes. Personally, with the revival of her country-esque, Wild West imagery, I get a very Debut vibe—a very Taymily vibe.

In the way that Midnights held references to previous life events, TTPD does the same, but in a way that is yellowed with age and stained with tea and coffee from the desks of everyone on the sentencing committee.

I don’t think this is the exact end of the chapter, not yet. It’s album 11—the 11th hour. I think it’s a poetic primer for the course we’re about to set foot into—album 12 (midnight).

I think after the Eras Tour ends, we’ll see some shifts. Not toward a bright and shiny new future—because I think after the past few years the Barbie Doll image is starting to wear on her—but toward a change nonetheless.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I miss them. 🥲

Btw the red scarf 🧣 was actually a pink flamingo bandana.

youtube

496 notes

·

View notes