#Swain is her father by proxy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

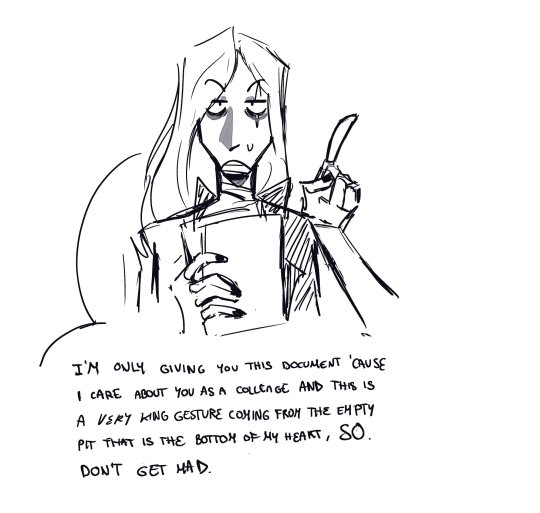

Katarina webcomic has paved the way for the arguably funniest dynamic in league

The other one

#league of legends#jericho swain#swain lol#katarina du couteau#katarina lol#swain league of legends#katarina league of legends#Swain is her father by proxy#technically

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Throne of Glass Rewrite, part the fourth

On the fifth night Lillian woke, certain that she was somehow late, that the guards were going to drag her out, maybe by her hair as they had the once, and throw her bodily into the mines. Her arm had broken when she had landed at the bottom of the shaft, and she knew she would have to work anyway unless she wanted to be useless. Useless people died, in Endovier.

Someone had hauled her to her feet and shoved a pickaxe into her left hand, her right arm dangling uselessly, and hissed, “Don’t let them see.”

She hadn’t. She’d learned to work with her left hand and arm, and when her right arm had eventually healed thanks to hurried splinting and covert extra rations – just a tiny amount, but even that was a treasure in the mines – she could use both arms for nearly anything.

She was not in Endovier, she reminded herself, looking up at the stars, unable to move for long moment from sheer terror. She was out. She could feel a breeze on her face, and at her side slept Glory, who woke when Lillian buried her fingers into the dog’s fur.

Glory snuffled at her and licked her face before rolling over to sprawl once more. Lillian did not go back to sleep, but she did relax, muscle by muscle and moment by moment.

The rest of the weeks-long journey went much the same way: Lillian would wake at odd hours, convinced she was about to be in trouble, but Glory was inevitably there to slobber on her. Lillian got better at going back to sleep.

They stopped the last day, Rifthold in sight. It glinted in the distance, light from the setting sun sparking off the windows and glass-topped towers. Lillian watched it.

“A waste of money, if you ask me,” the prince said, making her flinch. She hadn’t heard him come up behind her, or the two guards that walked with him. She watched him carefully as he continued, “The windows are impractical for siege. And the servants are constantly having to take time to clean the glass.”

She said nothing – she knew better than the prince the cost of cleaning the glass. The outside of the windows had to be cleaned as well as the inside, and the servants had rigged a clever contraption they could raise and lower, made of a large board and rope. The problem was that ropes were breakable and accidents inevitable: Lillian’s neighbor had lost a brother when he had fallen from several stories up to the flagstones of the courtyard.

There was something in the prince’s tone, too, something like one of her more persistent suitors when she was still at the shop. Tenric had always talked at her about how terrible the lot of the injured veteran was without listening to her thoughts as the daughter of one of those injured veterans, and he had always expected her to be impressed that he cared.

Did Dorian Havilliard expect her to be impressed that he knew his windows had to be cleaned?

“Don’t you have questions?” he demanded when she still did not respond. “You haven’t even asked what you’re supposed to be doing.”

“I’ll do whatever you ask, your highness,” Lillian said.

“If you’re really broken this could end badly,” he muttered, running a hand through his hair.

It did not seem as if he was waiting for an answer, so she looked at the city.

Buildings sprawled on either side of the wide river, the sides shored up with stone that legend held was fae work. It certainly did not seem to have seams or need mortar, she knew from trips to the harbor mouth on free days with the teens her own age. She hadn’t had many close friends growing up, but most girls wanted to be on the good side of the relatively well-off shopkeepers’ daughter who would tailor hand-me-downs or add some embroidery around collars or wrists for next-to-nothing. Lillian had had many suitors too – she was her parents’ only child, and her skill and the shop’s reputation guaranteed a steady income.

It helped that she had been pretty, she knew. It hadn’t been something she’d thought about often – or at least, she hadn’t thought she thought about it often – until the mines, when her hands roughed and formed callouses larger and rougher than those required for needlework, and her blonde curls had been chopped off and she could count her ribs. She’d caught herself worrying about those things sometimes, as if the hair or her soft hands were irreplaceable, before she’d reminded herself that the callouses made work easier and the hair was inconsequential to living.

She could maybe think about those things again, now that she was out. If what the prince wanted from her wasn’t too frightful.

“There’s a competition, of sorts,” the prince said. “I need you to win it.”

The only competition she would win in was how quickly she could turn out a dress, and she wasn’t sure of that after the mines. Maybe she could win a salt-mining contest.

Glory trotted up with a quiet woof and licked her hand. Lillian gripped her ruff so she had the courage to say, “What sort of competition?”

The prince eyed his dog narrowly, but Glory only thumped her tail twice on the ground and nuzzled Lillian’s hip.

“The sort that weeds out incompetents,” he said.

She hoped he was prepared to be disappointed quickly. Maybe something of that thought showed on her face.

“I don’t expect you to be in perfect shape immediately. We’re here early – there will be time for you to get at least a little bit of your prowess back.”

“You took me out of the mines for a game?” she asked, gripping Glory’s ruff a little more tightly. She could not decide if she was angry or scared or only resigned: of course the prince of Adarlan would take someone he thought to be a notorious assassin from her prison for a game.

“My father in his infinite wisdom,” the prince said, and she was not sure if she imagined the hint of sarcasm there, “has decided to make the heirship a competition. My brother and cousins have a sudden taste of what it could mean to have real power, and they want to keep it.”

What parent would force their children to fight? Lillian thought. But then, of course the prince and his royal family wouldn’t fight it out themselves. Of course they would have proxies.

“I am your only hope at staying out of those mines, Sardothien,” he continued. “Only if I win will I have the power necessary to do it.”

“And you chose me,” Lillian said, choking back laughter. She wasn’t entirely successful, if the look on the prince’s face was anything to judge by. Still. “Me.”

“I chose the greatest assassin I’ve ever heard of,” he said.

Lillian couldn’t help it – the laugh she let loose was hoarse and loud. She was out of practice. “It seems to me that an assassin you’ve heard of is a poor assassin.”

“Maybe,” he said. “Or maybe I’m just looking for a killer.”

Glory whined at Lillian’s too-tight grip. She let go immediately and petted the dog in apology.

It made sense to choose an assassin to kill people. She hadn’t wondered or cared, because it was a way out, but now she knew. The worst Lillian had ever done to anyone was shoving a too-persistent swain into a horse trough. Could she kill someone, if it meant she never had to mine salt again? Could she kill someone if it meant never setting foot in Endovier again?

She would do anything to stay out of Enovier, she decided. Even if she didn’t win, she could find other ways. If she died in the contest she wouldn’t even have to worry about it.

Lillian realized that while she would do anything not to go back to Endovier, she might do the same to continue living.

“I can be your killer,” she said.

9 notes

·

View notes