#St Ives Medieval Faire

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Found this wild jousting incident and the video it's from makes basically no mention of it.

The horse looks shaken but uninjured. The knight (Cliff Marisma) went on to win the tournament. So everyone was relatively okay in the end.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Article "Edward IV"

The fifteenth century English civil war that became known as the "Wars of the Roses" arose out of tension between the rival houses of Lancaster and York. Both dynasties could trace their ancestry back to Edward III. Both vied for influence at the court of the Lancastrian King Henry VI. The growing enmity that existed between these two noble lineages eventually led to a pattern of political manoeuvring, backstabbing, and bloodshed that culminated in a contest for the crown and Edward of York’s seizure of the throne to become Edward IV, first Yorkist King of England.

Born at Rouen on April 28, 1442, Edward was the eldest son of Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, "The Rose of Raby". Dubbed “The Rose of Rouen” due to his fair features and place of birth, Edward sported golden hair and an athletic physique. Growing to over six feet tall, the young Earl of March developed into the conventional medieval image of a military leader, ever ready to enter the fray. Intelligent and literate, Edward could read, write, and speak English, French, and a bit of Latin. He enjoyed certain chivalric romances and histories as well as the more physical aristocratic pursuits of hunting, hawking, jousting, feasting, and wenching. Edward proved time and again to be a valiant warrior and competent commander, personally brave and at the same time capable of understanding the finer points of strategy and tactics. As king, he displayed a direct straightforwardness and lacked much of the devious cunning exhibited by some of his contemporaries.

Young Edward of March became embroiled in the dynastic struggle between the Houses of Lancaster and York while still a teen. The family feud erupted into violence for the first time on May 22, 1455, when Yorkist forces under command of the Duke of York and the Earl of Warwick, and Lancastrian forces under command of the Duke of Somerset and King Henry, came to blows on the streets of St. Albans. After a disastrous debacle at Ludford Bridge on October 12, 1459, the Yorkist leaders fled for Calais and Ireland. Edward, Earl of March, was among those declared guilty of high treason by an Act of Attainder passed by Parliament on November 20.

In the summer of 1460, the Earl of March sailed from Calais to Sandwich with the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick and two-thousand men-at-arms. During Edward’s first proper taste of battle at Northampton in July of that year, he and the Duke of Norfolk co-commanded the vanguard that eventually breached the Lancastrian field fortifications, thanks in part to the traitorous actions of the Lancastrian turncoat Lord Grey of Ruthyn. After the Yorkist victory at Northampton, Edward’s father returned to England and made clear his desire to become king, but the assembled lords failed to support his claim.

With the contest between Lancaster and York still undecided, Edward was given his first independent command. He was sent to Wales to quell an uprising led by Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke, while his father marched out of London to tackle the northern allies of Henry VI’s Queen Margaret of Anjou. Drawn out of Sandal Castle by the appearance of a Lancastrian army, Richard of York fell in battle outside its walls on December 30, 1460. His severed head, along with those of his younger son Edmund, the Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, the Earl of Salisbury, soon adorned spikes atop the city of York’s Micklegate Bar. A paper crown placed on his bloody pate mocked the Duke’s failed bid for the throne. On the site of his father's death, Edward later erected a simple memorial consisting of a cross enclosed by a picket fence.

Now Duke of York, Edward gathered an army in the Welsh marches to avenge the deaths of his father and younger brother. Having spent his boyhood in Sir Richard Croft’s castle near Wigmore, Edward was well known in the region. He made ready to march toward London to support the Earl of Warwick, but then turned north to face an enemy force led by the Earls of Pembroke and Wiltshire. A strange sight greeted the anxious Yorkist troops at Mortimer's Cross that frosty dawn of February 2, 1461. Three rising suns shone in the morning sky. Quick to declare this meteorological phenomenon a positive omen, Edward announced that the Holy Trinity was watching over his army. After his victory at Mortimer’s Cross, Edward added the sunburst to his banner and badge. To make clear that the conflict had entered a more savage phase, Edward ordered the execution of Owen Tudor and nine other captured Lancastrian nobles. Tudor’s severed head went on display on the market cross at Hereford, where a mad woman combed his hair, washed his bloody face, and lit candles around the grisly memorial.

On February 17, the Earl of Warwick suffered his first defeat at the second battle St. Albans, brought about in part by treachery within his ranks. However, London refused to open its gates to Queen Margaret’s looting Lancastrian army, a force the citizens of the capital feared was full of northern savages. Reunited with King Henry, but frustrated by London’s mistrustful citizenry, the queen withdrew her forces toward York. Warwick and what troops he had left then met up with the victorious Edward at either Chipping Norton or Burford on February 22.

Greeted by cheers, Edward and the Earl of Warwick, marched into the capital on February 26. Warwick’s brother, the Chancellor George Neville, asked the people who they wished to be King of England and France. They answered with shouts for Edward. On March 4, 1461, the Duke of York rode from Baynard’s Castle to Westminster, where the Yorkist peers and commons and merchants of London formally proclaimed him King Edward IV.

The new Yorkist king’s official coronation was postponed while he prepared to set out in pursuit of Margaret and Henry. After sending Lord Fauconberg northward at the head of the king’s footmen on the 11th, Edward marched out of the capital on the 13th. He issued orders prohibiting his army from committing robbery, sacrilege, and rape upon penalty of death. He followed the trail of pillaged towns and razed homesteads left behind by Margaret’s northern moss-troopers.

On March 22, Edward received word that his enemies had taken up position behind the River Aire. On March 28, his vanguard tangled with a Lancastrian force holding the wooden span at Ferrybridge. Outflanking the defenders by sending a part of his army across the Aire at Castleford, Edward managed to push his men across the bridge and up the Towton road.

The two armies drew up in battle order on a snowy Palm Sunday, March 29, 1461. At some point during the morning the snow shifted, blowing into the faces of the Lancastrian soldiers. Taking advantage of the favourable wind, Fauconberg ordered his archers forward. The ensuing volley initiated the biggest, bloodiest, and most decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses.

Edward displayed steadfast courage as the battle raged. The young king rode up and down the line and joined in the melee whenever the ranks appeared ready to waver. No quarter was given, for both sides wished to settle the issue once-and-for-all, and the dead piled up between the opposing men-at-arms. At times, the fighting momentarily ceased while the bodies of the slain were pulled aside to make room for continued bloodshed.

After several hours of fierce fighting, the Yorkist line began to give way. However, the arrival of the Duke of Norfolk’s reinforcements tipped the balance in the Yorkist favour, and the exhausted Lancastrian army eventually faltered and broke. Many fleeing soldiers were cut down by Yorkist prickers in an area now known as Bloody Meadow. As was allegedly his habit when victorious, Edward may have given orders to spare the commons but slay the lords. Those Lancastrian nobles that survived the slaughter, along with King Henry, Queen Margaret, and their son Prince Edward, sought sanctuary in Scotland.

Victory at Towton established the Yorkist dynasty, but over the next three years Edward’s rule still faced a series of Lancastrian-inspired rebellions. Many of these uprisings against the Yorkist crown centred on Lancastrian strongholds in Northumberland. Most of Queen Margaret’s moves in the years immediately following the battle revolved around control of various castles, with some rather dubious aid from the Scots. In 1463, Margaret was finally forced to flee to France when Warwick and his brother routed her Scottish allies at Norham. Left behind by his queen, Henry VI held state in the gloomy fortress at Bamburgh. Warwick besieged this stronghold during the summer of 1464, and it became the first English castle to succumb to cannon fire. Captured in Clitherwood twelve months later and abandoned by his queen and allies, the Lancastrian king was sent to the Tower of London. Edward's throne finally seemed secure. However, Edward next faced threat from an unexpected corner as Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, turned on the man he helped make king.

In 1464, Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville, a comparatively lowborn Lancastrian widow. This caused a rift to form between the king and the Earl of Warwick. Edward's in-laws began to exert a growing influence over his court. Displeased with his own waning influence, in 1469 Warwick orchestrated a rebellion in the north. Edward remained in Nottingham while his Herbert and Woodville allies suffered defeat at Edgecote on July 26, 1469. The king then fell under Warwick's protection. On March 12, 1470, Edward was able to rout the rebels at the battle of Losecote Field, a moniker that arose from the fact that many men fleeing the battle discarded their livery jackets displaying the incriminating badges of Warwick and Edward's treacherous brother, the Duke of Clarence. With their treachery made plain, Warwick and Clarence sailed to France and formed an unlikely alliance with Margaret of Anjou. When Warwick returned to England with his new Lancastrian allies, Edward the lost support of the country and fled to the Netherlands. Warwick "The Kingmaker" reinstated the Lancastrian monarch during Henry's Readeption of 1470-1.

Edward IV spent his time in exile assembling an invasion fleet at Flushing and trying to woo his wayward brother back to the Yorkist cause. On March 14, 1471, Edward returned to the realm he claimed as his own, landing at Ravenspur. The Duke of Clarence promptly deserted Warwick and marched to his brother’s aid. Edward headed for London and entered the capital on April 11. Reinforced by Clarence’s troops, Edward took King Henry out of the capital and led a swelling army to face Warwick at Barnet. Edward suffered an early setback as he clashed with his one-time ally on that misty Easter morn of April 14, 1471. The Yorkist left collapsed, and the centre was slowly pushed back, but confusion caused by the obscuring fog eventually doomed Warwick's army. Warwick’s soldiers mistook the star with streams livery worn by the men of the Lancastrian Earl of Oxford for Edward’s sun with streams and loosed volleys of arrows into the approaching troops. With cries of “treason”, Oxford’s men left the field. Sensing the unease that rattled the Lancastrian ranks, Edward rallied his men and pressed the attack. Under this renewed pressure, Warwick’s army wavered and broke. The earl tried to flee the battlefield, but Yorkist soldiers pulled him from his saddle and despatched him with a knife thrust through an eye. Edward arrived on the scene too late to save Warwick from such an ignoble fate.

On May 4, Edward once more led his troops into battle, this time against Queen Margaret’s army at Tewkesbury. Margaret and her son, Prince Edward, had landed at Weymouth with a small force the same day of Edward’s victory over Warwick at Barnet. Under the leadership of the Duke of Somerset, the Lancastrian force moved toward Wales to try to join forces with Jasper Tudor. Wishing to bring Margaret’s army to battle before it crossed the Severn, Edward gave chase. He caught up with Somerset and Margaret at Tewkesbury. Though his army was slightly outnumbered, the Yorkist king once again triumphed over the Lancastrians. Margaret's son, Prince Edward, was captured and slain. Some Lancastrian fugitives, including the Duke of Somerset, tried to seek sanctuary in Tewkesbury Abbey. Dispute surrounds the exact details regarding what happened inside. Edward either granted pardons to those sheltering within the abbey walls, and then reneged on his promise, or he and his men entered the building with swords drawn. Either way, those captives that survived the slaughter were subsequently executed.

With the exception of quickly quelled Kentish and northern revolts, Edward’s triumph at Tewkesbury signalled the end of Lancastrian opposition to his reign. Margaret was captured and brought before Edward on May 12. She remained his prisoner until ransomed by King Louis XI of France. After making his formal entry into London on the 21st, Edward arranged the clandestine murder of poor King Henry VI. Edward’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, entered the Tower that evening. By the next morning, Henry, the potential focus of future Lancastrian resistance to Yorkist rule, was dead.

Following his final victory, Edward IV reigned over a relatively stable, peaceful, and prosperous kingdom. Once the Yorkist usurper secured his throne, he showed a ravenous appetite for the opulence of royalty and eventually became rather overweight. As king, he ordered the construction of several grand churches. He was also known as a patron of the arts. A lover of luxury and keenly aware of the political power of a majestic presence, one of Edward’s first acts a few months after his return to the throne was the expenditure of large sums of money on a magnificent new wardrobe. The other crowned heads of Europe all recognized him as legitimate King of England. His brief war with France in 1475 ended when Louis XI agreed to pay Edward an annual subsidy. By 1478 Edward had paid off the debts amassed by his one-time enemies. Unlike many of England’s medieval kings, he died solvent. He introduced several innovations to the machinery of government that the Tudors later adopted and developed. However, his second reign was not without its troubles. Woodville influence over his court caused tension between Edward and the nobility. In 1478, Edward’s in-laws manipulated him into eliminating his disgruntled brother George, the Duke of Clarence. Edward died on April 9, 1483.

Edward of York had a remarkable military career. He personally commanded and fought in five separate battles, and never lost a single one. As a leader of armed men, he often displayed daring and dash. As leader of the Yorkist cause, he exhibited a contradictory mixture of magnanimity and ruthlessness. As king, Edward IV worked to elevate the crown above the nobility and did much to restore a sound government. Unfortunately, his rash marriage bore bitter fruit, sowing the seeds of disaster for his young sons. Edwards’s death in 1483 left a minor as heir. The Duke of Gloucester was named protector of the princes Edward and Richard. Gloucester eventually had his nephews declared bastards and had himself proclaimed King Richard III. His nephews may have been murdered in the Tower, perhaps under Richard’s direct order. Faced with an invasion force led by Henry Tudor, and betrayed by his barons, Richard fell in battle at Bosworth Field. His death marked the end of the Yorkist dynasty and the ascendancy of the Tudors.

The Poleaxe of Edward IV

Being a fierce fighter as well as a skilled commander, Edward was said to be especially proficient with that uniquely knightly pole arm, the poleaxe. A magnificently decorated example currently residing in the Musee de l’Armee in Paris, France, has been ascribed to that most aristocratic of medieval monarchs. The connection to Edward IV is dubious, but this beautiful weapon certainly belonged to some extremely wealthy French, Dutch, or English nobleman of the late fifteenth century. Any consummate warrior and lover of luxury such as Edward of York would certainly have appreciated how the weapon’s combination of fine fighting qualities and rich ornamentation.

Having more reach than a sword, the poleaxe was often the preferred weapon when men of rank fought on foot. Topped by a spike, the axe head was backed by either a hammer or a quadrilateral beak. Mounted on a haft about six feet long and wielded in both hands, the poleaxe could cut, bludgeon, and stab. Even though the example attributed to Edward’s ownership sports fine decorative elements, it still exhibits all the qualities of a functional weapon. A pronged hammer backs a slightly curved axe blade. A wickedly sharp, stout spike thrusts out of the hexagonal central socket. A sturdy rondel acts as a hand-guard.

The lordly embellishments of the Edward IV poleaxe set it apart from simpler period examples. It is profusely decorated with chiselled gilt bronze. The iron components emerge from the throats of stylized beasts. The socket is further decorated with engraved foliage, a knot of flowers, and a cluster of fiery clouds. The rondel takes the form of a full-blown heraldic rose. The assumption that this weapon once belonged to Edward IV arose from the fact that it exhibits the symbols of rose and flame, but such ornamentation was common in the fifteenth century. Still, this imagery does echo the white rose en soliel device Edward used on his banner and badge, so it may just be a weapon once wielded by that accomplished Yorkist warrior.

Sources

Arms and Armour from the 9th to the 17th Century by Paul Martin

Arms and Armour of the Western World by Bruno Thomas

Battle of Tewkesbury 4th May 1471 by P.W. Hammond, H.G. Shearring, and G. Wheeler

Battles in Britain and Their Political Background:1066-1746 by William Seymour

The Book of the Medieval Knight by Stephen Turnbull

Campaign 66: Bosworth 1485: Last Charge of the Plantagenets by Christopher Gravett

Campaign 120: Towton 1461: England's Bloodiest Battle by Christopher Gravett

Campaign 131: Tewkesbury 1471: The Last Yorkist Victory by Christopher Gravett

Men-at-Arms 145: The Wars of the Roses by Terence Wise

The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses by Philip A. Haigh

Who's Who in Late Medieval England by Michael Hicks

#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers and poets#nonfiction#article#history#medieval#edward iv#military history#biography

1 note

·

View note

Text

boutta join the costume competition at the medieval faire wish me luck

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Witcher cosplay group, + the Geralt we ran into, at St Ives Medieval Faire on Saturday

I was really nervous about my Regis cosplay (even had a couple of worry-induced dreams where I found my gloves ruined), but I got so much positive feedback about pretty much every part of it that I’m now just super proud of it all.

I’m going to be cosplaying him again next week on the Sunday of Oz Comic Con with the same Yennefer.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Jousters, vikings and eagles: the St Ives Medieval Faire – in pictures | Culture | The Guardian)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Queen and the Page by Marianne Stokes

'It was a page without renown,

Blonde was his hair, light was his mein,

And he bore up the silken gown

Of the young Queen.'

THERE ONCE WAS A KING

Heinrich Heine, 1844

In the 1890s the Austrian-born Marianne Stokes (neé Priendelsberger) was drawn to romances from European folklore and literature for inspiration. In this mode she painted St Elizabeth of Hungary Spinning for the Poor in 1895 and Aucassin and Nicolette in 1898 (Sotheby's, New York, 29 October 1987, lot 190). These pictures contrasted with her earlier Realist style demonstrated in pictures like Lantern Light of 1888 (sold in these rooms 17 May 2011, lot 69).

The quotation inscribed upon the painting is from the 1844 German poem by Heinrich Heine's There Once was a King which told of the fated love of a page for his mistress and her reciprocal love for him. The painting was described as ‘…an imaginative work of great power and beauty, depicting the story of Heine’s poems. The lady is walking through the fair grounds of the palace pleasaunce – her train carried by her attendant and lover. Both are in sumptuous attire, and one hardly knows which to admire the more – the magnificent gold brocading of the Queen’s robes or the exquisite embroidery of the page’s dress. Highly decorative in scheme – charming in colour and elaborate in detail.’ (St Ives Weekly Summary, 11 April 1896) The art critic Wilfrid Meynell wrote of the picture; ‘… In the grêle lady the artist has drawn a clear round-browed Piero della Francesca profile with delicately hollow eyes, expressive of some threat of evil destiny. The feeling in the design of the figure has sweetness and distinction…’ (quoted by Magdalen Evans, Utmost Fidelity, 2009, p.64)

The Queen and the Page was owned by George McCulloch (1848-1907), whose collection of modern art was outstanding. He was an Australian mining engineer whose collection of over 300 paintings included masterpieces by the Pre-Raphaelites Burne-Jones and Millais and the High Victorians Alma-Tadema, Waterhouse, Hacker, Dicksee and Moore but also included a very fine representation of the best of the British Impressionists, Clausen, La Thangue, Gotch, Forbes and Whistler. He owned Stokes’ The Goatherd which was allied in style to the pictures by Bastien Lepage that he also owned. However The Queen and the Page and his other picture by Stokes Primavera, marked a transition between the work by the Pre-Raphaelites and the British Impressionists, capturing the romance of the former and the modern approach to painting of the latter. When McCulloch’s collection was surveyed by a correspondent for the Art Journal in 1897, The Queen and the Page was singled-out for praise; ‘In another picture by Mrs A.S., which hangs in Mr McCulloch’s gallery, we are taken at one step from fact to fiction, from a world of realism to another where fancy reigned. The Page, this second canvas, in no way pretends to record any phase of the life about us. It is purely imaginative, a pretty phantasy treated in the spirit of medieval romance and in feeling and manner akin to the quaint tapestry designed, with the execution of which in bygone centuries great dames occupied their many hours of leisure. This technical character is the outcome of the convention which the artist has adopted in dealing with her subject, a convention based chiefly upon decorative essentials, and disregarding almost entirely the possibilities of realism. The background, against which the figures are relieved, is a landscape indeed, but the trees, the sea, and the distant hills, which are combined to make it up, are treated simply as flat colour surfaces, filling important colour spaces, and by their arrangement providing a pleasant pattern of lines and hues. The figures themselves are in quite consistent with the medieval atmosphere of the picture. In dress, manner and appearance they have litter to connect them with the present day. The pale, wan page with his spare figure and somewhat sorrowful cast of countenance, and the demure princess with her close fitting robe and golden crown, are drawn from a fairy-tale world untroubled by modern thoughts and ways. The artist has made something of a contrast between the two faces, between the expression of hopeless devotion which is worn by the lad, and quiet unconsciousness of the maiden whose train he bears; but the contrast is purely a poetic one, and is not accentuated by the melodramatic touch.’ (A.L.Baldry, ‘The Collection of George McCulloch Esq.’, The Art Journal, 1897, p.72)

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you don't mind answering, what are some things that you really, really wish you'd see more of in depictions of medieval Scotland/Early Modern Scotland?

I absolutely don’t mind answering, thank you for asking!

I’m told there are some better quality novels than there are tv shows and films, so there are some aspects that have been done in good novels (though I’m not so familiar with them). There are so many things though that could be done on screen:

- Chiefly I spend a lot of my time wishing that there was more attention paid to the actual geographical make-up of Scotland and its regional variety, e.t.c beyond just splitting everything into Highland/Lowland, or just portraying everyone as being part of a Clan in the Highland sense, or just sticking everyone in Edinburgh as if that was the only place where anything happened. Orkney was very different to Galloway, and the Borders were very different to the Western Isles, and Ross was different to Aberdeenshire.

Now if this was true for the sixteenth century, it is even MORE true for the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries. Between the early Middle Ages and the end of the thirteenth century, Scotland was settled by a lot of different cultures- so in the twelfth century for example, much of the country (the traditional heartland of ‘Scotia’ north of the Forth) may have spoken Gaelic but Lothian had been settled by speakers of Old English some centuries ago and their language became Scots in time, and spread north of the Forth into Fife, Angus, Aberdeenshire and elsewhere so that by the sixteenth century it was much more widely spoken and the language of government. The south-west, especially the area around the Clyde and Glasgow was a British kingdom for a long time, speaking a language not dissimilar to Old Welsh- this kingdom had (sort of) disappeared by the mid-twelfth century but the language took a while to completely disappear. Up in Orkney, Shetland, and Caithness, rather like in Iceland and the Faroes, Norse settlers had taken over and Norse culture has still left traces there today. From the fourteenth century, Scots began to take over in the Northern Isles but there was still a very clear Norse background in the sixteenth century. Meanwhile in the Western Isles, the Norse newcomers did not manage to erase Gaelic so completely as they did in the Northern Isles, but they did leave their mark on the Hebrides, to the extent that the inhabitants in the Western Isles in the in the twelfth century were descendants of both cultures- they are sometimes called Gall-Ghàidheil in Gaelic, meaning ‘foreigner Gael’. Then over the course of the twelfth century more new immigrants moved in. The ranks of the nobility were swelled by Norman, Breton, and other French settlers- unlike England, there was no ‘Norman Conquest’, and the process was more gradual, but although the French language never had the same power in Scotland as it did in thirteenth century England, these settlers left their mark on the feudal system and other aspects of Scottish society, and in turn they too were affected by the cultures they encountered in Scotland. Other smaller pockets of immigration existed- immigrants from Flanders and the Netherlands, for example, were instrumental to developing Scottish towns and improving agriculture. In the east coast burghs of Fife and Lothian you can still see some architectural elements that may have been the result of trade with the Dutch- crow-stepped gables and red pantiles for example.

Although most of these cultures have altered and changed by the sixteenth century, the fact remains that the cultural backdrop to fourteenth or fifteenth century Scotland was a real mix- Gaelic, English, French, Norse, Flemish, British- and, perhaps, whatever it was that the elusive Picts left behind beyond their wonderful stone monuments. I have perhaps oversimplified things here but the point is that mediaeval and early modern Scotland was not a cultural monolith- something which both Scottish and foreign film-makers would do well to remember.

There are also changes to these regions across the years- Orkney going from being a Norwegian/Danish territory to becoming part of the Scottish kingdom, or the borders which had some of the best farmland and richest abbeys in the country in the thirteenth century becoming a very militarised and rather lawless zone after the Wars of Independence. I think it would be really interesting to see that portrayed on screen.

- Ok so that was the fundamental thing, apologies for the rant. But to go with that, more understanding of the landscape and architecture. In all fairness most tv shows and films involving Scotland, no matter how bad they are, at least have some lovely panning shots of the Highlands but there’s more to the country than Glencoe- you could really work with views like the sun on the sea from the Carrick coast or the beautiful if ruinous religious architecture- like the abbeys of Melrose or Arbroath or somewhere like Elgin Cathedral or Rosslyn Chapel or Inchmahome Priory.

- Costuming! Again this fits into the regional thing a bit, but it’s also more general. It’s a quibble I have with almost any medieval media but especially when it comes to Scotland people get really lazy with the costuming and just slap some shortbread tin stuff together rather than putting any thought into it.

- More traditional music! A surprising number of ballads and songs that are still popular among folk singers today are thought to have their roots in early modern if not mediaeval Scotland. And again the musical heritage of Scotland is varied depending on the culture it comes from.

- More properly developed female characters. Even though half the historical films made about Scotland are about Mary Queen of Scots, there are almost no good depictions of historical Scotswomen- and that’s NOT because there aren’t any interesting women in Scottish history before the modern period! There are lots of fascinating women’s stories from mediaeval and early modern Scotland, and although we are often frustrated by a lack of sources, we know they were there. More importantly, even if every woman was not a Certified Bad-Ass, as a whole women in Scottish history are not invisible and we can often see them in the records, whether operating in domestic, business, religious, or political contexts. Oddly, in their quest to show how Uniquely Misogynistic and Evil the Scottish nobility were to Mary Queen of Scots or Margaret Tudor or whoever, film-makers often end up ignoring women’s stories and therefore perpetuating the sexist view of history they claim to hate. (Though, yes mediaeval and early modern Scotland WAS misogynistic- but show me a country that wasn’t. Also it was misogynistic in a slightly different way to some other countries). I could list off dozens of interesting Scotswomen who lived before 1603- even though we sometimes can’t tell that much about their inner lives from the surviving sources, it’s obvious they were of some importance. And again it fits back into the cultural variety thing, because that was not limited to Lowland, Scots-speaking noblewomen.

- More art and literature and architecture and education and music and EVERYTHING. Scotland lost a LOT during the Reformation and due to Anglo-Scottish warfare (that’s what happens when the main centre of your kingdom is near to a border). But we know that, though it was sometimes an out of the way place, Scotland could be just as heavily tied into European cultural trends as any other northern country. And there are some beautiful surviving cultural artefacts that hint at a more vibrant past- both produced in Scotland (in the Gaelic and Scots-speaking environments) and imported from abroad.

- Equally on that note, more focus on its connections to countries other than England. Scotland had three universities by 1500, and yet many Scottish students still went to study abroad, especially in France, but also in England, the Low Countries, Italy, and elsewhere. An Italian humanist taught at the Abbey of Kinloss away up in Moray in the sixteenth century, and Scottish thinkers were in touch with other great minds of the day. Scots also fought abroad (see mercenaries in Sweden, or James IV’s support given to his uncle the king of Denmark, or the Garde Écossaise), and traded heavily across the North Sea (there were multiple Scots merchant colonies on the continent, not least at Veere). Scotland’s relations with Norway, Denmark, the Low Countries, the Papacy, Ireland (both as part of the kingdom of England and with individual Irish families), and other countries could be almost as important as its relationships with France and England. The eternal triangle of Scotland, England, and France, was not actually always the story- there were occasions when England and France played very little role in Scotland’s foreign affairs, let alone its domestic history.

- In particular an acknowledgement of the high quality of Scots poetry in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries wouldn’t go amiss.

- This is one which applies to all mediaeval media- but a more varied and interesting depiction of mediaeval religion would be good. In Scotland, this was also linked to the way people saw their own history- any sixteenth century Scot would have known some of the native saints, and anyone half-educated might have heard the names of David I and St Margaret and Columba, and known where the great abbeys in the kingdom came from.

- Actually a basic knowledge of Scottish history and legends beyond a few famous names. For example family was important in noble society- just because the stereotypical The Clans Are Gathering model is massively inaccurate, doesn’t mean that noble families in Scotland didn’t care about ancestry and kinship. But it would be great if tv shows and movies could actually think about how to portray that- and it really shows how little some of these scriptwriters know about their characters when they’re supposedly obsessed with the honour of the clan but the only piece of their country’s history they know is the name William Wallace. If you’re portraying the Douglases- even the earls of Angus who weren’t directly descended from him- the legacy of Sir James Douglas would have been a source of some pride. For actual ‘clans’, you could be dealing with some of the clans in the west of Scotland who, like some families in Ireland, claimed descent from Niall of the Nine Hostages. Some family histories got warped along the way- the Stewarts, for example, seem to have forgotten that they were descended from a Breton named Flaald by the fifteenth century and instead latched onto a story involving a character named Fleance (the one who later appears in Macbeth). As for legends- you could have a lot of fun with the different kinds of fairy belief that existed in Scotland, from the Borders (where it inspired ballads like Tam Lin) to the Highlands, or you could bring up legendary figures that are shared with other countries like King Arthur or Fionn Mac Cumhaill or Robin Hood or Hector of Troy. Sometimes the legends even cross over into real life- Thomas the Rhymer, hero of ballads and fairytales, seems to have been based on a real person who lived in the reign of Alexander III; while stories about William Wallace and Robert Bruce often became folk tales in the tradition of other greenwood outlaws like Robin Hood.

I think it’s pretty evident that my main issues with depictions of mediaeval and early modern Scotland on tv and film are largely because it’s so utterly unlike anything I see in the historical record. I’d love to list specific details and characters I’d like to see portrayed on screen, but before we even get to that point, the whole Generic Portrait of Scotland needs to change, because it doesn’t currently feel very realistic or interesting. All I really want is for the same level of research to be done with regard to Scotland as is done for England or France or any other country- England is often portrayed inaccurately, but there’s still at least 200% more effort put in than for Scotland.

On that note though, James I’s career (or at least the early fifteenth century as a whole) has been ripe for a television adaptation for years. Also I’m personally fascinated by ordinary rural life, patterns of agriculture and landholding, e.t.c. so even just an ordinary story set in an early sixteenth century fermtoun would be cool. But I don’t really think these stories would make any sense to people if Scotland was just portrayed the way it usually is - a generic country with no culture beyond a few scraps of tartan and alcohol and Anglophobia.

Thank you for the opportunity to rant, and apologies for the screed! I couldn’t express my enthusiasm very concisely I’m afraid. I genuinely don’t mind if there’s some inaccuracies to portrayals of Scotland, but now all portrayals are exactly the same and almost wholly inaccurate so it gets frustrating.

16 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Joust a plaisance at St. Ives Medieval Faire 2018

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On June 11th 1488 the Battle of Sauchieburn took place, where King James III and the Royalist army fought against his son and a collection of disgruntled nobles.

As this post covers the death of another of our monarchs as well as the battle itself it is a bit longer than my usual offerings.

Everyone knows the Battle of Bannockburn, fought in 1314 between the Scots and the English. The Second Battle of Bannockburn isn’t so well known – it was renamed, in fact, in 1655, perhaps to avoid confusion with its more celebrated predecessor. Known today as ‘The Battle of Sauchieburn,’ it was fought in more or less the same location as its more illustrious predecessor. The Battle also was known by The Battle of Stirling, another famous victory for us Scots that is more famous. But that’s where the similarities end.

The details of the battle are unclear, though it seems to have been as much a series of small-scale skirmishes as an organised engagement, but its consequences were grave nonetheless. By its end the reigning King of Scots was dead and his army routed, leaving his son to succeed to the throne unchallenged.

The Battle of Sauchieburn tends to be overlooked, perhaps on account of the qualities of the young man who gained most from it. Prince James, Duke of Rothesay went on to become one of Scotland’s finest medieval kings: James IV. Though he’s often remembered as much for his untimely and unfortunate demise at Flodden the positive impact James had upon his nation cannot be underestimated. He promoted Renaissance flair throughout his kingdom: a keen patron of the arts and sciences, he was a cultured and intelligent prince who longed to dazzle on a European stage, and to a certain extent he succeeded, with buildings like Linlithgow Palace rivaling contemporary equivalents across Europe.

But there’s no escaping it. The beginning of James IV’s reign was at best murky, at worst extremely suspect. To be fair the young Prince had no part in his father's ultimate demise, stories differ on how he met his end, it is unknown whether James III was killed in the battle or whilst fleeing. He is buried at nearby Cambuskenneth Abbey, which you may remember I visited and posted pics of last summer.

In the aftermath of the battle, the new regime took great pains to distance themselves from the killing. James IV himself made prominent acts of atonement: throughout the rest of his life, he publicly sported an iron chain around his waist as an acknowledgement for the part he played, and his coronation procession was led by a man carrying St Fillan’s bell, a holy relic reputed to cure mental affliction. James’s coronation, incidentally, took place on an auspicious day - the anniversary of the other Bannockburn , June 24th.

So what pissed the nobles off? Well there isn't a great deal written about this online but, on the one hand he was accused of !dissaitful and perverst counsale" I supoose that covers a multitude of sins. The second accusation was off course a much more serious crime, even today some people will resonate with it...." the inbringing of Inglsmen to the perpetuale subiccieone of the realm".

Fingers were also pointed at those who’d assisted in the provision of this ‘dissaitful and perverst council’ in the last few years of James III’s life. Chief offenders were the former Lord Advocate, John Ross of Montgrennan and one of his closest familiars, Sir John Ramsay, Earl of Bothwell. Tellingly, both men fled to England when the battle turned in the rebels’ favour, where they were welcomed at the court of Henry VII. There they seem to have busied themselves in the task of actively supporting a fifth column against James IV’s rule: unrest continued during the early years of James IV’s reign , though with the return of Montgrennan and his subsequent appointment to the Privy Council a year or so later the dust finally settled on what had been an inauspicious period in James’s kingship.

Looking a wee bit more into why the rebellion happened the late King had suffered six disastrous years throughout which his authority was progressively eroded. The rot started in 1482 in an incident that has earned historical notoriety, not for James’s role in it, but for the actions of Archibald Douglas, Earl of Angus, who was much later dubbed ‘Bell the Cat’ for the leading part he allegedly played in it. James had mustered the host at Lauder to counter a very real threat from south of the border, but instead suffered a rebellion amongst his nobles and then saw a number of his closest advisers hanged. The same John Ramsay of Bothwell who later fled the country after Sauchieburn was also present here: aged just eighteen at the time, he supposedly escaped death by clinging tightly to the king, who begged fervently for the young man’s life to be spared.

The debacle at Lauder conveys the impression of an ineffective monarch railroaded by his nobility, those in favour were fine with it, it was the rest of them that conspired to remove him from the throne, and no matter how much they conveyed shock at his demise, these things rarely end without the loss of life!

James took the throne age 8th after his father's love of modern artillery cost him his life when he got too close to a cannon that exploded at Roxburgh. When he reached age to govern himself he initially did well, winning Berwick back from the English, he also further extended his Kingdom with the marriage to Margaret of Denmark, bringing Orkney and Shetland into his realm. In later years Berwick would fall again and it didn't go down well with his subjects.

Towards the start of the rebellion Prince James found himself progressively stripped of powers and authority by his father, who favoured instead his second son, also called James. The "inbringing of Inglsmen" again rears its head hear, orin this case Inglswomen as the father tried to negotiate a marriage with Edward IV of England's daughter, Catherine of York. Oh and two sons called James? Well the story goes that at the time the younger was born the older was seriously ill and seemed unlikely to survive, but it is unclear whether there is any evidence for this hypothesis. In late mediaeval Scotland it was not uncommon to have two brothers with the same name, occasionally there were even three!

So it’s small wonder that the prince felt compelled to join the rebels. At the time, he may have been genuinely afraid for his future if not indeed his life. Remember though he was still in terms of today's world an adolescent at around 14 years old when the rebellion was brewing. He appears to have been seized by the rebels at Stirling, where he was subsequently paraded as a hostage and then set up as a puppet king. But James was intelligent, and able and charismatic. I suspect he was fully in command of the situation and he knew full well what he was doing. Perhaps his father, growing increasingly unpredictable and erratic, left him no other choice.

Tradition states that James III fell from his horse and was injured. He called for a priest, but the robed figure who came to take his final confession was an imposter: instead of providing succour and comfort, the so-called ‘priest’ stabbed and killed his king. A few weeks later he was laid to rest at Cambuskenneth with all the pomp and ceremony customarily bestowed upon a monarch, the mourners led by his contrite son. But the killer was never found, nor was there ever any real appetite to pursue them. Well the story might not be true but four noted chroniclers tell this story, although they were told almost 200 years later and the authenticity of this account of his death has often been called into question.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Victims of the Childbed - Isabella of Aragon, Queen of France

A Princess of Aragon by birth, Isabella was the seventh of ten children born to King James I of Aragon and Violant of Hungary. Isabella was between the ages of three and five when her mother, an intelligent and politically talented woman, died. Her upbringing was likely quite conventional for a girl of her rank. King James had many dealings with his neighbors in France and Navarre, mostly in the form of land or succession disputes. In 1258 he signed a treaty with King Louis IX of France. Around this time, James probably put preteen Isabella forth as a bride for Louis’ heir Philip in order to cement the peace between their nations.

On May 28, 1262 Isabella was married to Prince Philip at Clermont. She was fourteen Philip was three years older at seventeen. Nothing is known of these early years of the marriage, save that Isabella carried out her dynastic duty. In 1265, 1268, and 1269 she bore three sons: Louis, Philip, and Robert. Then in 1270, Philip left to join his father on the Eighth Crusade. That same year, Isabella’s fourth son Charles was born. A few months later King Louis was dead of dysentery while on his crusade. Philip hurried back to France to be crowned king, and Isabella was now Queen of France. When Philip returned to the Crusade Isabella accompanied him.

Isabella and Philip spent several months on Crusade in Tunis. It seems that immediately before or after their arrival Isabella became pregnant with her fifth child. The royal party stopped in Calabria, Italy on the way back to France. It was here on January 11, 1271 that Isabella fell from her horse. The fall triggered early labor at only six months gestation. She quickly delivered a stillborn son. Isabella languished for seventeen days, weakened by both her injuries and the traumatic birth. She died on January 28 in her twenty-second year. Her body was transported back to France and was interred at the Basilica of St. Denis.

Isabella’s toddler son Robert also died the same year as his mother. In 1274, Philip remarried to Marie of Brabant. Two years later, Isabella’s eldest son and Philip’s heir, Louis died under suspicious circumstances. He was said to have been poisoned by Philip’s new queen, who sought to eliminate Philip’s elder sons so that her own son could be his heir. Nevertheless, Philip was succeeded by his and Isabella’s son Philip. King Philip IV “The Fair” is one of the most famous (or infamous) medieval French kings. He also went on to father another Isabella, who became Queen of England and is known as the formidable mother of Edward III of England. Isabella and Philip’s youngest son Charles was made Duke of Valois and founded the Valois Dynasty, which ruled in France for three centuries.

#first post in this series in months where I haven't felt ready to kill the husband#refreshing#he even bothered to mourn her for a while#Isabella of Aragon#Queen Isabella of France#house of Capet#France#Philip III of France#victims of the childbed#art#my art

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Video Source]

Solid tip historical jousting at St Ives Medieval Faire 2018

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Muse’s Profile - Carter (Supernatural OC)

Fandoms

Supernatural (main)

From Dusk Till Dawn

Atomic Blonde

The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

General

Name: Ada Carter-Trevelyan

(Formal English: Lady Ada Trevelyan)

(Formal Russian: Ada Erastovna Valenkova)

Goes by: Dr Carter

Title: Baroness Trevelyan, a minor aristocrat owning a small estate in Porthzennor, Cornwall, encompassing a stately home and a lighthouse. Other assets on the land, including a farm and a tin mine, were sold off in the 1890s to cover the family’s debts. The family acquired the double barrelled surname, Carter-Trevelyan, around this time, after marrying into a wealthy merchant family to avoid losing the estate entirely.

Born: August 1st 1924, in a lighthouse near St Ives, Cornwall

Species: human/zombie

Age at time of story: 92

Apparent age: 43

Relationships

Parents: Marian Elizabeth Carter-Trevelyan, Erast Nikolaievich Valenkov

Other notable family: Lord Arthur Percival Carter-Trevelyan, grandfather, Irene and Varya Stepanova, cousins

Romantic interests: Ketch, though “romantic” is debatable

Sexual interests: Ketch

Friendships: none, though she develops some degree of platonic affection for Dean

Allies: Dean, though somewhat shakily. Ketch, even moreso.

Enemies: Alastair, somewhat, though she generally takes a neutral stance on demons; the Thule Society

Appearance

Hair: black, generally kept long but with an undercut to disguise the bald patches resulting from radiation poisoning

Eyes: grey

Complexion: pale, freckles

Markings: several scars covering most of her back and chest, with scar tissue replacing her left nipple, white scar tissue on her left upper arm, frequent bruises and puncture marks on her inner elbows that have variable rates of healing, left ring finger is slightly crooked following a broken knuckle

Height: 5’8”

Weight: 130lb

Build: toned, but almost sickly thin due to the effects of radiation sickness, small chest and narrow hips that give her an almost “boyish” shape

Tastes

Attire: casual, typically jeans/tank tops/combat boots, favors black

Drives: black Jeep Renegade, later a black Chevrolet Colorado

Music: Celtic/folk, classical, swing, hard rock, also very fond of Vera Lynn

Food: can taste very little due to nerve damage, only able to taste hot food such as chillis or curry

Drink (soft): coffee, but has to be strong and black for her to taste it, able to taste tea with a preference for Yorkshire Gold

Drink (alcoholic): Stolichnaya vodka, sometimes Glenfiddich Scotch

Colors: black, navy, hunter green

Hobbies (rarely practiced anymore): playing piano, boxing, fencing, hunting, horse riding, Cossack dancing (from her father), old time dancing (from her mother)

Hobbies (still practiced): shooting, open water swimming, reading

Likes: living in America, the seaside, and anything that makes her nostalgic for her childhood

Dislikes: sex, though she does like the power play of it; hypocritically, posh or upper class elites; taking orders; socialising; any of the organisations she used to work for, such as MI6, the BMoL, or the CIA; basically, anything that reminds her of the parts of her past she’s ashamed of

Skills

Former profession: lighthouse keeper, spy (WWII and Cold War), medical student

Current profession: demon doctor, alchemist

Practical skills: traditional boxing, horse riding and hunting (learned from her father), fencing, hand-to-hand combat, ranged weapons, sharpshooting, combat medicine, Western medicine (specialising in cardiology), Middle German and English alchemy, medicinal alchemy, torture

Language skills: fluent in English, Russian and German, conversational in Dutch and French, knows a small amount of Cornish

Preferred weapons: fists, knuckle dusters, handguns in combat. For torture, she’s master of the scalpel.

Special abilities: above average strength as a result of the formula, accelerated healing, immunity to almost all diseases

Personality

Traits: cynical, threatening and sarcastic with a dry sense of humor, she can be arrogant and frequently overestimates her own abilities, with terrible consequences. She projects an image of being cold and uncaring, but on occasion her inner feelings of compassion and affection inadvertently show through. Once established, those feelings are often intense and set in stone.

Qualities: assertive, confident, loyal, perceptive, smart, resilient, unprejudiced, principled, fair

Flaws: abrasive, complacent, jealous, vindictive, wrathful, selfish, cruel, manipulative, often fails to meet her own moral standards

Strengths: her intellect, physical strength and skills, excellent poker face, strategic ability, and good judgment of character

Weaknesses: arrogance, complacency, reluctance to admit her own vulnerabilities, easily manipulated once those vulnerabilities are found, emotional dishonesty, sometimes cowardice

Morality: she believes torture is justified in the case of a) punishing terrible people, or b) serving the greater good, though it isn’t clear how much she truly subscribes to this belief at heart. As of the 21st century, she chooses to harvest blood from demons so as to avoid torturing humans unless absolutely necessary. Her personal philosophy is that the worst of humanity is worse than any monster, and includes herself in that as having the capacity to do terrible things.

Fears: her own past

Triggers: corkscrews, the specific phrase “Was ist dein name?”

Religious views: none

Political affiliation: after benefitting greatly from Nye Bevan’s NHS following the war but suffering under a communist regime while undercover in the USSR, she leans cautiously left, though politics has little direct effect on her anymore

Alignment: true neutral, leaning good/evil or lawful/chaotic at different times in her life

Sexual orientation: asexual, but with a Machiavellian attitude towards sex where she views it as a game for power rather than a pursuit for pleasure

History

Her father was a Russian Cossack who fled to England following the revolution, being wanted by the Bolsheviks for trying (and failing) to defend the life of a Russian aristocrat. The aristocrat in question (having married into the Russian aristocracy) was the niece of an English Baron and retired naval captain who owned land in Cornwall, who agreed to take in Erast and permitted him to live in the lighthouse on his land as a gesture of gratitude after hearing his story.

The Baron’s daughter, politically active suffragette Marian Carter-Trevelyan, eventually fell in love with Erast and the pair married in July 1923, with Ada arriving a year later.

Baron Trevelyan was also active in the House of Lords, a keen alchemist, and member of the Men of Letters, who taught Ada much of what she knows about alchemy and the supernatural growing up. During the war, he sat on the government’s secret occult war council and recommended his granddaughter for a role spying on the Nazis - a private education had ensured her fluency in German and several other vital skills. Ada trained with the WAAF and underwent special training between 1939 and 1941 before airdropping into Frankfurt, along with an American agent, Roland Jefferson, at age 17.

Ada worked as a spy for the Allies during WWII to sabotage the Nazis’ occult program, where the Thule tried to develop a formula that would render their soldiers immortal based on an alchemical recipe from the 1500s.

Ada’s cover was blown in 1944 following a Russian telegram sent with a compromised encryption (suspected sabotage). She was imprisoned and tortured for several months, before escaping with the help of the Dutch resistance shortly before VE Day. The medieval text containing the alchemical recipe was brought back to England and placed in the custody of the Men of Letters.

During her absence, Baron Trevelyan was killed during the Blitz in 1942 when a bomb landed on the Men of Letters’ HQ. Her parents, after traveling to London to retrieve the body, were also caught in a bombing raid and killed less than a week later. Ada returned to England to find almost her entire family dead, the exceptions being her housekeeper, Mrs Hogarth, and the family cat, Grigory.

For a time after the war, Ada attended medical school before being asked to return to work for MI6 against the Russians. Part of this work involved torturing enemy agents, where she used her advanced knowledge of human anatomy to devastating effect.

Later, during the Cold War while undercover in Siberia, Ada suffered acute radiation poisoning from close proximity to a nuclear test site. She was, at this time, 43. While dying she used the Nazis’ formula combined with her blood to preserve her own life, albeit it in a “zombie-like” state - this was the first successful implementation of the formula, which sustains her to this day.

The active ingredient in the formula - the blood of someone in excruciating pain - she now supplies by performing surgery and medical enhancement procedures on demons in exchange for a fee, benefiting both parties. (For example, medical or alchemical enhancements granting demons certain abilities, powers, or immunities, requiring a painful procedure that allows Ada (now going by only the name ‘Carter’) to harvest the blood. Carter doesn’t disclose this, but rather charges for her services.)

After hearing about her in passing from Crowley, Dean approached her to help deal with his health issues that arose after being stabbed by Metatron and from the Mark of Cain.

Later, Dean reached out to Carter again to help find Kelly Kline and deliver her nephilim child. Instead, Arthur Ketch got to her first and prevented this, though the two struck up an unusual alliance in the process.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Going to St Ives Medieval Faire this weekend as Regis with a Witcher cosplay group.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Getting my Viking on.. 🧔🏼👍 (at St Ives Medieval Faire) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2wCSsHgt0p/?igshid=oig81io7vmkk

0 notes

Photo

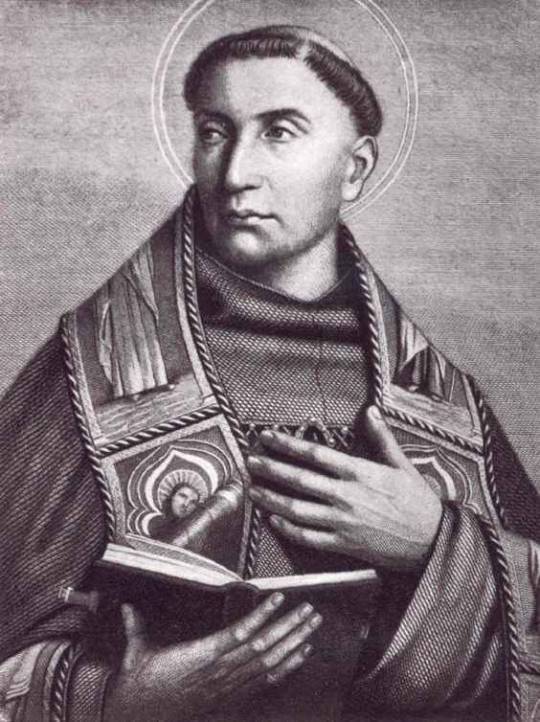

Saint Bonaventure - Feast Day: July 14 (Latin Calendar) - July 15 (Ordinary Time)

The baptismal name of St. Bonaventure, the "Seraphic Doctor", was Giovanni. He was the son of Giovanni di Fidanza and Ritella, born at Bagnorea near Viterbo, Italy in 1221. As a young man he joined the Roman Province of the Franciscans and was sent to complete his education at Paris University. Here he studied under Alexander of Hales, the English scholar who joined the friars and laid the foundations of the Franciscan school of philosophy and theology. Both as a student and later as a teacher in Paris, Bonaventure had St. Thomas Aquinas as his colleague and friend. They were associated in a defense of their respective Orders and the whole Mendicant version of the religious life against the attacks of the secular master William of St. Amour.

In 1257, despite his youth, Bonaventure was elected as minister general of the whole Franciscan Order, an exacting position which he filled for sixteen years almost until his death. The situation he had to face was delicate, the Order was internally divided between Spirituales or zealots for the literal observance of the Rule, and the Relaxati who desired mitigations. It is a tribute to his holiness as well as his abilities that he solved this problem so well as to merit the title of 'Second Founder' of the Friars Minor. At the general chapter at Narbonne in 1260 he gave the Order its first constitutions, and he was untiring in his visitation of the different provinces to see that his legislation was being put into practice. It was he also who organized the studies of clerics in the order and so made possible the wide apostolate of both learned and popular preaching which we have come to associate with the best of the medieval friars. He himself was a much-sought-after preacher to clerical and lay congregations, to regulars and seculars, to the learned and to the simple. Nonetheless he managed all the time to put forth a series of writings bearing on Franciscan history and spirituality, as well as more general treatises on philosophy, theology and scripture which were the outcome of his Paris professorship. Among them we may signalize his Commentary on the Franciscan Rule, his biography of St Francis (a peace-making rather than a critical essay) and the celebrated Itinerarium mentis in Deum (Journey of the Soul to God) written in 1259 at La Verna, where St Francis had been stigmatized just thirty-five years previously.

The early controversy with William of St Amour was only the first phase in a long struggle to get the Franciscan ideal accepted in all contemporary circles. We find him upholding the same cause later against Gerard of Abbeville, and in the council of Lyons. He had also to curb the excesses of those of his brethren who followed the prophetic notions of the Calabrian Cistercian, Joachim of Flora, and looked for the establishment of an apocalyptic 'eternal gospel' of which the 'Spiritual' Franciscans would be the natural heralds. On a wider plane, we see him helping to resist the rise of 'Latin Averroism' in the philosophical arena at Paris.

It is, however, as a saint and as one of the greatest of mystical theologians, that he was prized by contemporaries and is still studied by the enlightened. Everyone was impressed by his authentically Franciscan devotion towards the Passion of our Savior; among his works is to be found an office of the Passion which he composed for the personal use of the saintly King Louis IX. Bonaventure was the first to give the mystical movement inaugurated by St Francis of Assisi a solid theological and psychological basis. His spiritual teaching, like his whole system of thought, centers about Christ. In him the tender affective love of Francis for the humanity of Christ is united with the traditional theology (rather than the newer Dominican Aristotelianism), and there is, in consequence, a stress on love and the part played by will rather than on knowledge and the part played by intellect. He did not hesitate to teach that an idiot might love God as well as the most learned divine. For him the Incarnation and Redemption are the crowning glory of God’s work for man, the supreme purpose of all creation and therefore, necessarily, the focus of all spiritual life. The practical goal of spiritual endeavor for all, according to Bonaventurian teaching, is a lofty contemplative prayer, union with the divine wisdom. This attitude is to be discovered in all that he wrote, but as an example of its explicit statement we may point to the much commented De triplici via (The Threefold Way), a miniature but nevertheless complete summa of medieval mystical doctrine.

His solid, even obstinate humility, enabled him to evade, in 1265, the burdens of the archbishopric of York to which he was appointed by Pope Clement IV, but it proved unavailing eight years later when Pope Gregory X compelled him to accept the see of Albano and made him a Cardinal. It is related that when the legates arrived with the red hat they found that the saint was doing the washing-up (cleaning the dishes). He asked them to hang the hat on the branch of a tree until he had finished. The last months of his life were passed in close association with the Pontiff in preparing for a forthcoming Ecumenical council by means of which it was hoped to reunite Greeks and Latins. When the council met at Lyons, St Bonaventure was its moving spirit until his premature death on July 14, 1274.

Although he had been an almost universal object of veneration during his life, for his saintliness and for his repute as miracle-worker, the process of his canonization was, owing to the unfortunate dissensions within his own Order, unduly deferred. The great popular esteem in which he was held may be gauged with fair accuracy from the prominent part assigned to him by Dante in Paradiso, XII, 127ff, where his disinterested spiritual outlook, even when holding high ecclesiastical office, fits him both to relate the story of St Dominic and to criticize some of his relaxed followers. The popular cult of St Bonaventure was greatly enhanced in 1434 when his remains were translated and his head found incorrupt. But it was still not until 1482 that he was canonized by Pope Sixtus IV. His tomb was plundered by the Huguenots, but the head was safely hidden, only to disappear finally in the troubles of the French Revolution. In 1588 Pope Sixtus V pronounced him a doctor of the universal church.

St Bonaventure is called the "Seraphic Doctor" because he revealed a certain warmth toward others as a divine fire. His leadership with the Franciscans, following St. Francis of Assisi, expressed itself by showing charity, goodwill and ardent affection toward others besides having great discernment in decision-making and judgment. He offers to help us, as will all those in heaven, when we petition him for help. We can truly be transformed and change our habits and attitudes only with divine assistance. We must help ourselves but most interior betterment only comes with divine assistance… Everyone loves cheerful, enthusiastic and unselfish givers. Our doctor’s generosity and kindness toward others were fervent and caring...St. Bonaventure tells us to look carefully at the crucified Christ. Gradually this practice will enable us to become more compassionate and understanding toward others. People will begin to see God in you, even if you do not...When we humble ourselves, reflect upon the crucified Lord often, and share unselfishly, acting with goodness toward others, Jesus mysteriously becomes alive in us, and is plainly seen by others… As a child Bonaventure was cured of a serious illness through the intercessory prayers to St Francis of Assisi. Later Bonaventure felt called by God to join the Order. He devoted himself, according to God’s will, to earnest study and prayer. God filled others with the fruits of his learning through his example, teaching and writings. The Order of Friar Minor (OFM), and the world, through Bonaventure, was renewed through his leadership and God’s graces.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Viking Spread, St Ives Medieval Faire, sep ‘16

#food#history#table#vintage#viking#35mm photography#35mm film#Black and White#black and white film#photography

5 notes

·

View notes