#Sons of Stribog

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sons of Stribog

Sons of Stribog A black and White image from Lusignan, ECD, Guyana

For most people who have followed my photography for any time, they know that I have a penchant for seascapes, and especially for high contrast black and white images of those scenes. This one falls right in to those. As a matter of fact this one is the latest addition to the ongoing Oniabo series of such images. This was taken with the Canon 60D using a Sigma 10-20 ultra-wide angle lens, this…

View On WordPress

#Black & White#black and white#Canon 60D#clouds#Guyana#Guyana South America#koker#Lusignan#Michael C. Lam#Michael Lam#photo#photograph#photography#ProfessorMC#seascape#Sigma 10-20#sky#Slavic#sluice#Sons of Stribog#South America#Stribog#The Michael Lam Collection

1 note

·

View note

Text

@certifiedsophist

Mock funerals of Morana and Yarilo belong to the exact same type of a holiday - a rather common form of ritual found in many cultures that is supposed to end one season and bring about another, and can be performed at the cusp of any season. There are many other rituals of this kind among the Slavs: funeral of rusalka, of a cuckoo, Maslenitsa, etc. The details and the character dying will vary but the principle remains the same.

Basically, every season of the year could have its special provody ritual that ended it. We can find the most striking similarities with the mock funeral of rusalka in the Kupalo festivities which took place on the summer solstice, that is on the Eve of John the Baptist, Ivan Kupalo (23rd–24th June), and in which a male ithyfallic effigy, called Kupalo, Jarilo, Kostroma, etc., was buried and sometimes resurrected again. Kupalo festivities took place near water and were replete with erotic symbolism, bathing, fire jumping, and dancing on the ritual fields called igrišta – church literature reprehended the orgiastic nature of this ritual.

Rusalki: Anthropology of Time, Death, and Sexuality in Slavic Folklore by Jiri Dynda

In some regions the start of spring was seen as domain of Yarilo (his very name is built from a word denoting spring or a year, which for the ancient Slavs most likely started in springtime). Western Slavs however seem to mostly celebrate Morana around this time, though of course we know Polabians had spring celebrations of Yarovit that didn’t survive the trial of time.

Similarly the summer solstice could be the domain of either, depending on the region. And so Kupalo/Kupala, another character belonging to the body of summer solstice rituals could be identified as related to either of them.

Some slavists studying Slavic midsummer rites came to the conclusion that they may represent a union of two deities, one of death and water the other of life and fire, and on the basis of some folk stories they further speculated the deities might perhaps be siblings connected by forbidden taboo love.

The idea that Morana and Yarilo as well as Perun and Veles need to remain separate at all times seems to me to be a neo-pagan addition. The concept of having to keep Perun and Veles separate was born because Veles was not among the deities whose effigies Prince Volodymyr placed on a hill outside his palace in Kyiv:

And Vladimir began to reign alone in Kiev. And he placed idols on the hill outside the palace: a Perun in wood with a silver head and a gold moustache, and Khors and Daždbog and Stribog and Simargl and Mokoš. And they offered sacrifices and called them gods, and they took their sons and daughters to them and sacrificed them to the devils.

- Tale of Bygone Years as translated in Sources of Slavic Pre-Christian Religion by J. A. Álvarez-Pedrosa

At the same time we know Veles did have an effigy in Kyiv but in a different spot.

And he himself (Vladimir), on entering Kiev, ordered the idols to be destroyed and beaten, breaking some and burning others, but he ordered the idol of Volos, who was known as the god of cattle, to be thrown into the River Pochaina, and the idol of Perun to be tied to a horse’s tail and dragged down the mountain by Borichev towards the river, appointing servants to strike the idols with sticks: this was not because the wood could feel, but to outrage the devil for deceiving us in that way. The infidels wept over this, as they had not yet received holy baptism.

- from the fragments of Life of Vladimir as translated in Sources of Slavic Pre- Christian Religion by J. A. Álvarez-Pedrosa

This is it - this is the reason people decided Perun-and-Veles-can-never-touch, even though we clearly also have sources mentioning them being invoked side by side:

Thus the Emperors Leo and Alexander made peace with Oleg, and after agreeing upon the tribute and mutually binding themselves by oath, they kissed the cross, and invited Oleg and his men to swear an oath likewise. According to the religion of the Russes, the latter swore by their weapons and by their god Perun, as well as by Volos, the god of cattle, and thus confirmed the treaty. (…)

But if we fail in the observance of any of the aforesaid stipulations, either I or my companions, or my subjects, may we be accursed of the god in whom we believe, namely, of Perun and Volos, the god of flocks, and we become yellow as gold, and be slain with our own weapons.

- Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text

It’s perfectly possible for gods to be opponents - functionally and mythically - and still be worshipped concurrently by the same people as part of the same pantheon. Additionally it’s important to remember that the pantheon of Volodymyr was likely a political tool and slavists have long debated how good of a representation for popular Eastern Slavic beliefs at the time it may be.

In principle, Vladimir’s pantheon was a response to internal socio-political changes and the external needs of the emerging Eastern Slavic state. It was a henotheistic and dynastic cult focusing on the deity which best served state building purposes - Perun. It was a product of the long evolution of the Eastern Slavic religion which in post-migration times diverged from relative conceptual unity of the common Slavic beliefs. Eastern Slavic beliefs evolved in specific geographic, ethnic and political conditions, characteristic of Eastern Europe. Its development was the response to those circumstances. Serving new needs and purposes, the Kievan cult had to incorporate new attributes and acquire a new dimension.

- Organized Pagan Cult in Kievan Rus’. The Invention of Foreign Elite or Evolution of Local Tradition? by Roman Zaroff

So tldr instead of solely looking at Morana and Yarilo separately as divine opposites I think it’s beneficial to look at both of them in the context of a larger body of similar Slavic rituals, some of which I presented in this post. Knowing how flexible those rites are can actually help significantly in building one’s personal sacred calendar to one’s needs.

64 notes

·

View notes

Note

Happy STS! What gods from our world's myths would you assign to your characters? Who would fit the best to your character and why?

Hi Jess, happy STS💜

I'd love to go with the Slavic gods, because it would be so on brand for the Sunblessed Realm. These deities aren't well defined, given veery few written sources, and their domains often overlap, so I'm slightly going by the vibes I get from them. Let's go with the main trio:

Lissan - Dazhbog. That's a sun deity, vaguely equivalent to Helios, and Lissan is sun-coded in the 'burning brightly and unstoppably ' sort of way, but is also associated with prosperity and well-being, which is Lissan's goal.

Ianim - Rod. God of family, ancestors, and fate. Ianim feels very much bound by family obligations and is anxious about living up to his family's expectations. But also, there's the fate vs. free choice aspect to his arc.

Gullin - Stribog. It's a wind deity, and Gullin's superpower is related to wind. Wind has also been referred to as 'son of Stribog' in at least one source that I've seen. But also Zeus. And not because of the weather aspect.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Slavic Iceberg Explained (Stolen from Reddit, all credit to OP)

1 level

Baba Yaga - famous witch-like entity, that lives in the house on chicken legs. Her features alone are worth the iceberg, but she herself is extremely well-known.

Three bogatyrs - bogatyr is the folk hero in slavic mythology. Most well-known bogatyrs are Ilya of Murom, Dobrynya Nikitich and

Alyosha Popovich, as all three of them are depicted in the famous painting.

Koschei the Deathless (or Kashchei) - the prototype for DnD liches, the immortal sorcerer and/or warrior, whose death is hidden in the needle that is hidden in the egg that is found in the duck that is somehow lives in the hare that is kept in the chest that is chained to an oak that is located on a faraway island. He’s one of the most popular Slavic fairy tale characters.

Leshy - a trickster spirit of forests that can appear in different forms and cause various levels of mischief (typically getting people lost in the woods).

Perun - a chief deity of Vladimir's pantheon, presumably a god of storms and warfare. He is one of the few gods that were mentioned more than once in literary sources, and many scholars suspect some Perun character traits were passed down onto the Slavic version of Elijah the Prophet.

Grandpa Frost (Ded Moroz) - holiday gift-bringer that is very similar to Santa Claus. He was mostly created by the Soviets in the early 20th century, but is also heavily inspired by St. Nicholas and Slavic spirit of winter named Moroz (which means just "Frost").

Zmey Gorynych - "Serpent of the Mountains", a three-headed serpent, an archetypical dragon (much more draconic than actual Western European dragons). He's also a very popular folklore character, but most commonly he's depicted as a nemesis for Dobrynya Nikitich. Zmey kidnaps people, breathes fire and takes care of a whole bunch of little serpent children.

Pushkin's fairy tales - Alexander Pushkin, who's widely regarded as the most famous Russian poet, had something of a phase of fascination with traditional folklore. As such, he wrote a bunch of fairy tales like "a tale about Tsar Saltan and his son Knaz Gvidon", "a Goldfish", "a tale about a Golden Rooster" and some others.

2 level

Primary Chronicle - a chronicle written by a monk named Nestor, that has some details on pre-Christian Slavic Mythology (among many other things). It is also our primary (pun kinda intended) source for the Kievan Rus history studies.

The Tale of Igor's Campaign - an anonymous epic poem written in the Old East Slavic language (allegedly told by the mythical poet Boyan). It details a failed raid of Igor Svyatoslavich (d. 1202) against the Polovtsians of the Don River region. It gives a bit of an insight into the worldview of 11th century Rus' people and mentions a lot of mythological characters like Veles and Khors.

Domovoi - a household spirit, whose attitude towards people can vary from positive to outright hostile. Much like with Baba Yaga, there’s way more tales about Domovoi than I’m able to list here.

Veles ~ Volos - one of the most well-known Slavic deities (or two, if Veles & Volos are somehow different), presumably the god of cattle, trade and arts. Some of his qualities seem to be transferred onto Saint Blaise (because their names are kinda similar) and also onto Saint Nicholas for some reason.

Kolobok - a round piece of bread that came alive for unexplained reasons. It is a character of a popular fairy tale, fairly similar to the gingerbread man.

Vladimir's pantheon - according to the Primary chronicle, Vladimir was a ruler of Kievan Rus who attempted to unify Slavic beliefs by building a big shrine for six deities — Perun, Khors, Mokosh, Dazhdbog, Stribog, Semargl.

Talking animals - magical talking animals (most commonly horses) are often presented as necessary for the folkloric hero to complete an impossible task.

Vladimir, the Red Sun - a very popular character in the bylinas, loosely based on the historical Vladimir. He is commonly depicted as a ruler of Kievan Rus and has an authority over bogatyrs

Nightingale The Robber - an enigmatic nemesis of Ilya of Murom, a robber who possesses the ability to whistle with enough force to uproot trees and instantly kill most people. Some accounts say that Nightingale the Robber belongs to the Mordvin people

"Magical bride" tale format - a very popular Slavic fairy tale plot involves a powerful magical woman and either attempting to win her over or saving her from kidnapping. Sometimes both.

Vodyanoi - the spirit of a river or a lake, who can drown people, commands fish and can require a sacrifice

Self-setting tablecloth - a popular magic item. When you roll this tablecloth over a table, it magically summons food and drink

Imps - little demons are very popular antagonists (and sometimes just creatures doing their thing) in Slavic folklore and can occasionally substitute for other, more neutral spirits

Werewolfs/Volkolak - people, who turn into wolves, are widespread in Slavic mythology. They can be either cursed people or warlocks, shape-shifting by their own free will

Kikimora - a mean little female spirit that causes mischief and ruins the work. In different versions she can be a wife of Domovoi, a spirit of an unborn baby or an animated doll created by a witch.

Fern flower - one of the most famous magical plants. It was believed that ferns blossom only once a year, on Ivan Kupala night. The Fern Flower grants its user many magical abilities like knowledge of hidden treasure locations.

The Turnip - a pretty strange but popular fairy tale about an enormous turnip that grew in an old man's garden one day. To pull this vegetable out, he, his wife and their granddaughter needed the help of their dog, cat and even the little mouse

Buka and Babay - slavic versions of Boogeyman. Babay is sometimes described as an old man, who steals children and puts them in his bag. There are also other names for creatures like these, for example “Hoka”.

Yarila - a personification of a summer holiday, that seems to be a variation of the dying-and-rising deity. Yarila's customary celebration was basically a funeral, where his doll was mourned and buried. However, Yarila was a victim of many mystificators, who referred to him as a god of sun and love.

3 level

Neopaganism - despite having so little info on the actual mythology, Slavic Neopaganism is pretty popular. Unfortunately, many neopagans are also Nazis and/or following conspiracy theories, but there are some people who are actually interested in their culture and work with actual folkloric sources

Sadko - merchant and trickster from Novgorod bylinas. He was abducted by the Sea Tsar but saved himself with the help of Saint Nicholas (or, in some versions, the wife of the Sea Tsar)

Alkonost and Sirin - magical birds with woman heads. Their singing enchants people, making them forget everything and follow the source of the song. They were at least partially based on sirens from Greek mythology (and in Alkonost case - on mythological Alkyon).

Rusalka - the most iconic Slavic undead, unresting spirits of drowned maidens (or just maidens), who hunt people in summer and have a number of unnerving traits. However sometimes they are presented in a positive way — their presence can cause crops to grow better.

Swan-geese - the servants of Baba Yaga in one of the popular fairy tales. They are sentient birds that kidnap children for her.

Bannik - one of the many house-spirits, spirit of banya, traditional slavic bathhouse. He is pretty dangerous and can splash boiling water on someone or cause a heat stroke. However he can also tell the future, if you ask him the right way.

Hoaxes - unfortunately, pseudomythology, misconceptions and blatant lies plague the field of slavic mythology studies. Most notable hoaxes being “The Book of Veles” and “Slavic-Aryan Vedas”.

Svyatogor - a giant bogatyr who lives on the Holy Mountains (which he draws his name from), because in other places Earth just can't hold him. There are a couple of bylinas about him, and in one of them he dies after laying down into the suspiciously appropriately-sized coffin.

The Sea Tsar - a ruler of the sea folk and other sea creatures. He is rarely mentioned in folkloric sources. Sea Tsar's underwater parties cause storms on the sea

Poludnitsa - the Midday Maiden, the spirit of midday and sunstrike. She appears in different forms and can have different behaviors, but most often she attacks and kills those who work during the midday hours

Waters of life and death - artifacts that are often present in fairy tales. Water of death (contrary to its name) turns a disembodied corpse into a whole body, and water of life restores this body back to life

Rod & Rozhanicy - Rozhanicy are the spirits of fate that appear to the newborn baby in groups of three (much like Greek Moiras) and "grant" them their future fate. As such, a mother should follow certain traditions to appease them. Rod was mentioned together with Rozhanicy in some medieval sources, but doesn't seem to survive in more recent traditions, so there had been a lot of speculation about what was his deal.

Tugarin Zmey - an archenemy of Alyosha Popovich, a giant warlord, that may or may not be serpentine in appearance. He throws knives at Alyosha, while flying way up high on “paper wings”. Alyosha prays to the God, who sends a heavy rain, so Tugarin Zmey can't fly anymore and has to face our hero on the ground. Tugarin's name is of unidentified origin.

Witches and Warlocks - very popular characters in Slavic folklore. There are a lot of beliefs about them, and many of them separate "born" and "taught" witches. Though there are good witches and warlocks, most of them use their powers to magically steal others' goods like milk and grain.

Viy - the titular character of Nikolai Gogol's novella with the same name. It is described as a hideous being with long iron eyelids reaching its knees. Viy commands other demons, but this detail seems to be invented by Gogol, as well as its name. However, there are a multitude of characters that share its main characteristic - giant eyelids that they are unable to raise without help.

Upir - East Slavic name for vampire. Warlocks, heretics and people who died unnaturally or weren't properly buried can rise from their graves in the form of blood-sucking malevolent undead.

Bolotnik - the spirit of a swamp, typically a very aggressive creature that lures people deep into the swamp. The swamp was always considered a domain of demonic creatures.

Mother Moist Earth - a very popular deity that isn't mentioned in written texts, but was well-known in folklore even well after the advance of Christianity (although, of course she wasn't called a goddess, just some vague entity). Mother Earth embodies, well, everything connected to nature, like growing crops, and also seems to be the goddess of oathkeeping.

Fiery serpent - a type of doppelganger creatures that take the appearance of a dead or missing husband and feed off the energy of a woman

Mikula Selyaninovitch - the most powerful bogatyr ever, a regular farmer, who can lift the weight of the entire earth in his bag (in text it is referred to as "тяга", which can be translated as "gravitational force"). He's known as the son of Mother Moist Earth and prayed to as a saint.

Polenitsa - a gender-neutral substitute for "bogatyr", that was commonly used to describe a female warrior. Polenitsas are sometimes encountered in bylinas and tend to be stronger and smarter than male warriors

Peresvet and Chelubei - according to legends, Peresvet was an Orthodox monk, who chose to fight Chelubei - a mighty warrior from Golden Horde - during the battle of Kulikovo. Peresvet and Chelubei killed each other, but Peresvet managed to stay in the saddle after being hit by the spear, while Chelubei fell. Peresvet could've been a historical figure, but the battle is but a legend.

4 level

Folk Christianity - this term is used to describe beliefs and practices that exist in folk communities and includes a lot of elements from their original beliefs. Folk Christianity is a very important source of information about pre-Christian mythologies.

Serpent walls - these are huge and ancient fortifications of unclear origin, that span across Ukraine on the right bank of Dniepr and its tributaries. These fortifications are predominantly presented as ramparts of earth, which led to the creation of a legend about a mighty bogatyr (his name can vary) who has harnessed a serpent in a giant plow and furrowed him way to the Black Sea, where the bogatyr drowned his enemy.

Marya Morevna - a titular character of the story about your typical young prince, who fought Koshey and saved the girl. Interesting thing about Marya Morevna is that she A) presented as a mighty warrior and B) Her name sounds suspiciously similar to Marena or Marzhanna - South Slavic holiday character, a personification of winter and, according to some theories, death. If the latter is true, then it explains why Marya Morevna has a rivalry with Koshei the Deathless (although, please take all of this with a grain of salt)

Ripping grass - another magical herb from slavic folklore, a magical grass that supposedly can be used to tear open any door and unearth any treasure

Dove Book - or maybe the Deep Book, it’s pretty unclear. It is an apocryphal book that tells about… well, The Book of Dove, a giant divine book that fell from the sky. Tsar David and Tsar Volotoman arrive to see this phenomenon and engage in the dialog about the origin of the world and important locations and creatures. Despite being clearly Christian, the Book of Dove seems to borrow some elements from original Slavic mythology.

Volots - one of the words for giants in Russian (in Belarus they are called asilki). According to fragmented mentions, volots populated the world before humans, created mountains and rivers, fought serpents and were wiped out by the God himself for trying to fight God or just being generally nasty.

Lihoradka - these creatures are female spirits of disease. They often exist in groups from 7 to 77 and represent different symptoms like fever, muscle pain and jaundice. Sometimes they are said to be cursed daughters of Herod. In modern slavic languages “Lihoradka” translates to “fever”.

Domovoi is the ancestor's ghost - there are a lot of traits in this mythological creature that seems to suggest its original role as a helpful ancestral spirit. Domovoi often has the appearance of the oldest family member. Sometimes it’s even outright stated that the first one who enters a newly built house will become its Domovoi after death.

Chudo-Yudo - a serpentine creature that has multiple heads, but also seems to be human-like in appearance, as it rides a horse and has two pets - a dog and a raven (all three of them can talk). Typically there are three of them, each one stronger than the last. The strongest Chudo-Yudo sometimes possesses a magical ability to regenerate lost heads by touching them with its magic finger.

Different versions of Koshchei - Koshchei isn’t always depicted as Undying. In “Marya Morevna” he doesn’t seem to have immortality and was killed by the magical horse. Some tales use Koshchei’s name to designate another prominent folkloric figure - “a man who’s as tall as the fingernail, but with the beard as long as an arm”. Yeah, he doesn’t have a better name. Finally, bylinas have another Koshchei, who is just some kind of prince without any powers.

Iriy - Iriy or Vyrai is a mythical place where birds, insects and reptiles live in winter (sometimes it is said that birds and snakes have different Iriys). Iriy is said to exist in the West beyond the sea.

Flaming skull - skulls with fiery eyes are decorating the fence around Baba Yaga’s house. In one of the stories, she gives one of these skulls to a girl who helped her. This flaming skull then proceeds to immolate her abusive mother and stepsisters.

Spirits of prosperity - people with magical abilities can obtain a spirit of prosperity, who will steal goods from other people and bring them to its master. Those spirits can take many different forms like little humans, small dragons or black chicken.

Cabinet mythology - “cabinet mythology” is the term in Russian mythological study that designates any pseudomythological element that arises as a result of misinterpretation or deliberate misinformation by researchers. Examples of “cabinet deities” include Lada, Lel and Vesna.

White-eyed Chud - chud is the mythical tribe of the Russian North that fiercely fought colonizers and christianisation. Many of the chud killed themselves or retreated far into the forests. There are a lot of different takes on what chud really is, and this word was also use to designate several actually existing peoples.

Indrik - a giant unicorn-like creature, a king of beasts who lives underwater and uses its horns to dig up rivers. Indrik is mostly mentioned in books like the aforementioned Dove Book

Alatyr - a magical stone, whose power is often called upon in invocations. It is located in the center of the world on the Buyan island in the middle of the sea. Alatyr is considered “a father of all rocks”/

Witcher - Witcher or Vedmak is not that guy from video games and not just a male witch. Witcher has the power over witches and undead and can prevent them from causing harm (or support them). In other aspects vedmaks are pretty much the same as regular warlocks and witches.

The Slavic Iceberg

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New York Times Jews have converted to Byzantine Christianity. No icons of demonic Moses or demonic Christ are allowed in their churches.

Although Christianity had spread in the region under Oleg's rule,[citation needed] Vladimir had remained a thoroughgoing pagan, taking eight hundred concubines (along with numerous wives) and erecting pagan statues and shrines to gods.[21]

He may have attempted to reform Slavic paganism in an attempt to identify himself with the various gods worshipped by his subjects. He built a pagan temple on a hill in Kiev dedicated to six gods: Perun—the god of thunder and war, a god favored by members of the prince’s druzhina (military retinue)"; Slav gods Stribog and Dazhd'bog; Mokosh—a goddess representing Mother Nature "worshipped by Finnish tribes"; Khors and Simargl, "both of which had Iranian origins, were included, probably to appeal to the Poliane."[22]

Open abuse of the deities that most people in Rus' revered triggered widespread indignation. A mob killed the Christian Fyodor and his son Ioann (later, after the overall Christianisation of Kievan Rus', people came to regard these two as the first Christian martyrs in Rus', and the Orthodox Church[citation needed] set a day to commemorate them, 25 July). Immediately after the murder of Fyodor and Ioann, early medieval Rus' saw persecutions against Christians, many of whom escaped or concealed their belief.[c]

However, Prince Vladimir mused over the incident long after, and not least for political considerations. According to the early Slavic chronicle, the Tale of Bygone Years, which describes life in Kievan Rus' up to the year 1110, he sent his envoys throughout the world to assess first-hand the major religions of the time: Islam, Roman Catholicism, Judaism, and Byzantine Orthodoxy. They were most impressed with their visit to Constantinople, saying, "We knew not whether we were in Heaven or on Earth… We only know that God dwells there among the people, and their service is fairer than the ceremonies of other nations."[23

0 notes

Text

Russian Fairy Tales Test Prep: Pagan Deities

The best known roster of pagan deities is that of the six whose statues Prince Vladimir erected upon assuming sole rule of Kiev. According to the Primary Chronicle for the year 980, he “placed idols on a hill, outside the palace yard, a wooden Perun with a silver head and a golden mustache, and Khors and Dazhbog and Stribog and Simargl and Mokosh.” Missing from this list is Volos/Veles, the god of cattle (skotnii bog) and commerce, whose veneration in ancient Rus’ is widely attested, and by whose name (along with that of Perun) ancient Russians ratified oaths.

A. Perun/Bog

1. equivalent to: Lithuanian Perkunas, Latvian Perkons, Albanian Perendi, Roman Jupiter, Greek Zeus, Hittite Teshub, Norse Thor/Donar, Celtic Taranis. 2. primary sources: Nestor’s Chronicle, mid-6th century Procopius, 10th-century Varangian treaties 3. primary story: a creation myth, in which he battles Veles, the Slavic god of the underworld, for the protection of his wife (Mokosh, goddess of summer) and the freedom of atmospheric water, as well as for the control of the universe. 4. dvoeverie: After Christianization in the 11th century CE, Perun's cult became associated with St. Elias (Elijah), also known as the Holy Prophet Ilie (or Ilija Muromets or Ilja Gromovik), who is said to have ridden madly with a chariot of fire across the sky, and punished his enemies with lightning bolts.

In Slavic mythology: Perun was the supreme god of the pre-Christian Slavic pantheon, although there is evidence that he supplanted Svarog (the god of the sun) as the leader at some point in history. Perun was a pagan warrior of heaven and patron protector of warriors. As the liberator of atmospheric water (through his creation tale battle with the dragon Veles), he was worshipped as a god of agriculture, and bulls and a few humans were sacrificed to him. In 988, the leader of the Kievan Rus' Vladimir I pulled down Perun's statue near Kyiv (Ukraine) and it was cast into the waters of the Dneiper River. As recently as 1950, people would cast gold coins in the Dneiper to honor Perun.

Appearance & Reputation: Perun is portrayed as a vigorous, red-bearded man with an imposing stature, with silver hair and a golden mustache. He carries a hammer, a war ax, and/or a bow with which he shoots bolts of lightning. He is associated with oxen and represented by a sacred tree—a mighty oak. He is sometimes illustrated as riding through the sky in a chariot drawn by a goat. In illustrations of his primary myth, he is sometimes pictured as an eagle sitting in the top branches of the tree, with his enemy and battle rival Veles the dragon curled around its roots.

Perun is associated with Thursday—the Slavic word for Thursday "Perendan" means "Perun's Day"—and his festival date was June 21.

Reports: The earliest reference to Perun is in the works of the Byzantine scholar Procopius (500–565 CE), who noted that the Slavs worshipped the "Maker of Lightning" as the lord over everything and the god to whom cattle and other victims were sacrificed.

Perun appears in several surviving Varangian (Rus) treaties beginning in 907 CE. In 945, a treaty between the Rus' leader Prince Igor (consort of Princess Olga) and the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII included a reference to Igor's men (the unbaptized ones) laying down their weapons, shields, and gold ornaments and taking an oath at a statue of Perun—the baptized ones worshipped at the nearby church of St. Elias. The Chronicle of Novgorod (compiled 1016–1471) reports that when the Perun shrine in that city was attacked, there was a serious uprising of the people, all suggesting that the myth had some long-term substance.

B. Kors/Xors/Chors

- most frequently mentioned Slavic god, after Perun - dvoeverie: appears in the apocryphal work Sermon and Apocalypse of the Holy Apostles, which mentions Perun and Khors as old men; Khors is said to live in Cyprus. Khors also appears in the apocryphal text Conversation of the Three Saints, a text which combines Slavic + Christian + Bogomil traditions. In it, he is referred to as “an angel of thunder” and it is said that he is Jewish. - his functions are uncertain and there are multiple interpretations of his name.

1. Sun God hypothesis: associated with Dazhbog; in The Tale of Igor’s Campaign, Prince Vseslav, who “came to Tmutarakani before the cocks" and "Khors ran his way", traveled from west to east and thus reached the castle before the cocks crowed, and in this way "overtook" the Sun; his name means “rays.”

2. Moon God hypothesis: Prince Vseslav was called “wolf” and his journey takes place at night when the sun is absent from the sky; his name does mean “rays” but they’re the moon’s rays and not the sun’s rays.

3. Fertility God/Vegetation hypothesis: link between Thracian & early Slavic cultures indicates Kors is more of a Dionysus-type figure, who dies and is risen; like Dionysus, Dazhbog (who Kors is often linked to) has a double nature (Eastern Slavs assign him solar qualities, while Southern Slavs assign him chthonic qualities).

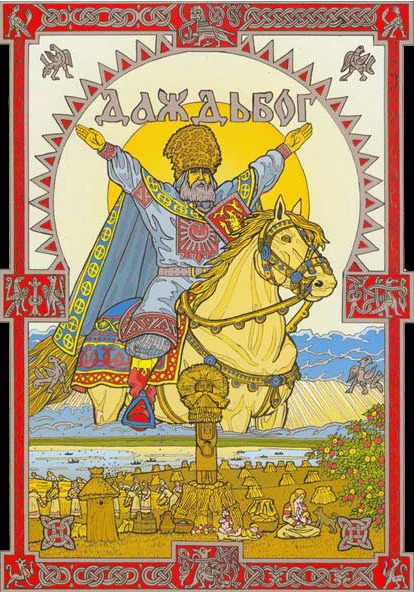

C. Dazhbog

1. equivalent to: Khors (Russian/Iranian), Mithra (Persian), Helios (Greek), Lucifer (Christian) 2. primary sources: John Malalas, The Song of Igor’s Campaign 3. family: Son of Svarog, brother of fire god Svarozhich, husband of Mesyats (the moon), father of the Zoryi and Zvezdy 4. primary myth: He resided in the east, in a land of everlasting summer and plenty, in a palace made of gold. The morning and evening auroras, known collectively as Zorya, were his daughters. In the morning, Zorya opened the palace gates to allow Dazbog to leave the palace and begin his daily journey across the sky; in the evening, Zorya closed the gates after the sun returned in the evening. 5. dvoeverie: There was a belief that each winter he would enter people's homes and gift gold to those who had been good. That belief passed into Christianity, especially in Serbia, and this visitor was called Položajnik. During Christianisation, his cult was exchanged with the cult of Saint Sava, while Dažbog became lame Daba - the most powerful demon in Hell. Reasons why he was demonized are various, possibly because his cult was the strongest in Serbia or because he was considered also as the god of Nav, the Slavic underworld and world of the dead.

In Slavic mythology: Dazbog was the Slavic sun god, a role that is common to many Indo-European people, and there is ample evidence that there was a sun cult in the pre-Christian tribes of central Europe. His name means "day god" or "giving god," to different scholars—"Bog" is generally accepted to mean "god," but Daz means either "day" or "giving."

His totem animal was a wolf, therefore wolves were sacred animals and killing them was considered a great sin. Wolves were considered to be messengers of Dazhbog, while he himself could shift into a white wolf.

According to one myth, Svarog became tired of reigning over the universe and passed on his power to his sons, Dazhbog and Svarogich.

Appearance & Reputation: Dazbog is said to ride across the sky in a golden chariot drawn by fire-breathing horses who are white, gold, silver, or diamonds. In some tales, the horses are beautiful and white with golden wings, and sunlight comes from the solar fire shield Dazbog always carries with him. At night, Dazbog wanders the sky from east to west, crossing the great ocean with a boat pulled by geese, wild ducks, and swans.

In some tales, Dazbog starts out in the morning as a young, strong man but by the evening he is a red-faced, bloated elderly gentleman; he is reborn every morning. He represents fertility, male power, and in "The Song of Igor's Campaign" he is mentioned as the grandfather of the Slavs.

4. Stribog

Very little is known about him, although he was clearly very important to early Slavic peoples. In the epic ”Slovo o polku Igorove “ it is said that the winds, the grandsons of Stribog, blow from the sea. This leads to conclusion that Stribog is imagined as an old person, since he has grandsons. The grandsons were the winds from all directions.

Eagle was the animal consecrated to Stribog. Plants consecrated to Stribog were hawthorn and oak. When pledges were made, Stribog was often warrantor. Festivities in Stribog’s honor were organized in the summer as well as in the winter. They were probably organized in the summer in order to invocate winds and rain, while in the winter they were organized in order to appease him. In the period of Christianization Stribog’s characteristics were overtaken by St. Bartholomew and Stevan vetroviti (windy).

5. Simargl/Semargl

- may be equivalent to Simurgh in Persian mythology, who is portrayed similarly (winged lion and/or dog). He can also take human form. - God of physical fire (as opposed to celestial fire; that’s Svarog) - He is said to be the husband of Kupalnica (or Kupalnitsa), goddess of night, from whom he got two children: Kupalo and Kostroma.

Zorya, solar goddesses who are servants or daughters of the deity Dazhbog, keep Simargl chained to the star Polaris in the constellation Ursa Minor. Should he break free and destroy this constellation, it will cause the world to end.

Why would he be worshipped in Rus’, you ask? A couple of possible answers: a. Eastern Slavs borrowed Simargl from Sarmatian-Alanian people and worshiped him. b. Eastern Slavs never worshiped Simargl. Just at that time, a significant number of Kiev residents were of Khazar and Sarmatian-Alanian origin. Vladimir included their deity in the pantheon to get their support.

6. Volos/Veles (also Vlas, Weles Vlasii, St. Blaise, or Blasius)

1. equivalent to: Velinas (Baltic), Varuna (Vedic), Hermes (Greek), Odin (Norse) 2. primary sources: The Tale of Igor’s Campaign, old Russian chronicles 3. primary myth: a creation myth, in which Veles abducts Mokosh (the Goddess of Summer and consort of Perun, God of Thunder). Perun and his enemy battle for the universe under a huge oak, Perun's holy tree, similar to both Greek and Norse (Yggdrasil) mythologies. The battle is won by Perun, and afterward, the waters of the world are set free and flowing. 4. dvoeverie: Velia remains a feast of the dead in old Lithuanian, celebrating the border between the world of the living and the world of the dead, with Veles operating as a role of guiding souls to the underworld. The battle between Perun (Ilija Muromets or St. Elias) and Veles (Selevkiy) is found in many different forms, but in later stories, instead of gods, they are complementary figures separated from one another by a furrow plowed by Christ, who converts them. Veles is also likely represented by St. Vlasii, depicted in Russian iconography as surrounded by sheep, cows, and goats.

In Slavic mythology: A second creation myth associated with Veles is the formation of the boundary between the underworld and the human world, a result of a treaty forged between Veles and a shepherd/magician.

In the treaty, the unnamed shepherd pledges to sacrifice his best cow to Veles and keep many prohibitions. Then he divides the human world from the wild underworld led by Veles, which is either a furrow plowed by Veles himself or a groove across the road carved by the shepherd with a knife which the evil powers cannot cross.

Veles is associated with a wide variety of powers and protectors: he is associated with poetry and wisdom, the lord of the waters (oceans, seas, ships, and whirlpools). He is both the hunter and protector of cattle and the lord of the underworld, a reflection of the Indo-European concept of the netherworld as a pasture. He is also related to an ancient Slavic cult of the deceased soul; the ancient Lithuanian term "welis" means "dead" and "welci" means "dead souls."

Appearance & Reputation: Veles is generally portrayed as a bald human man, sometimes with bull horns on his head. In the epic creation battle between Velos and Perun, however, Veles is a serpent or dragon lying in a nest of black wool or on a black fleece beneath the World Tree; some scholars have suggested he was a shape-shifter. In addition to domestic horses, cows, goats, and sheep, Veles is associated with wolves, reptiles, and black birds (ravens and crows).

Reports: The earliest reference to Veles is in the Rus-Byzantine Treaty of 971, in which the signers must swear by Veles' name. Violators of the treaty are warned of a menacing punishment: they will be killed by their own weapons and become "yellow as gold," which some scholars have interpreted as "cursed with a disease." If so, that would imply a connection to the Vedic god Varuna, also a cattle god who could send diseases to punish miscreants.

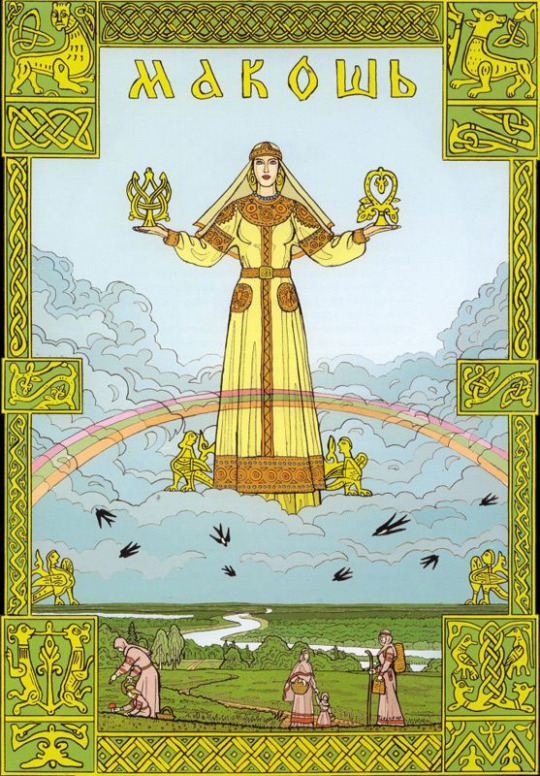

7. Mokosh

1. loosely comparable to: Gaia, Hera (Greek), Juno (Roman), Astarte (Semitic) 2. epithets: Goddess Who Spins Wool, Mother Moist Earth, Flax Woman 3. primary sources: Nestor Chronicle (a.k.a. Primary Chronicle), Christian-recorded Slavic tales 4. dvoeverie: With the coming of Christianity into the Slavic countries in the 11th century CE, Mokosh was converted to a saint, St. Paraskeva Pyanitsa (or possibly the Virgin Mary), who is sometimes defined as the personification of the day of Christ's crucifixion, and others a Christian martyr. Described as tall and thin with loose hair, St. Paraskeva Pyanitsa is known as "l'nianisa" (flax woman), connecting her to spinning. She is the patroness of merchants and traders and marriage, and she defends her followers from a range of diseases.

In Slavic mythology: The origins of Mokosh as mother earth may date to pre-Indo-European times (Cuceteni or Tripolye culture, 6th–5th millennia BCE) when a near-global woman-centered religion is thought to have been in place. Some scholars suggest she may be a version of Finno-Ugric sun goddess Jumala.

Mokosh, sometimes transliterated as Mokoš and meaning "Friday," is Moist Mother Earth and thus the most important (or sometimes only) goddess in the religion. As a creator, she is said to have been discovered sleeping in a cave by a flowering spring by the spring god Jarilo, with whom she created the fruits of the earth. She is also the protector of spinning, tending sheep, and wool, patron of merchants and fishermen, who protects cattle from plague and people from drought, disease, drowning, and unclean spirits.

Although the Great Goddess has a variety of consorts, both human and animal, in her role as a primary Slavic goddess, Mokosh is the moist earth goddess and is set against (and married to) Perun as the dry sky god. Some Slavic peasants felt it was wrong to spit on the earth or beat it. During the Spring, practitioners considered the earth pregnant: before March 25 ("Lady Day"), they would neither construct a building or a fence, drive a stake into the ground or sow seed. When peasant women gathered herbs they first lay prone and prayed to Mother Earth to bless any medicinal herbs.

Appearance & Reputation: Surviving images of Mokosh are rare—although there were stone monuments to her beginning at least as long ago as the 7th century. A wooden cult figure in a wooded area in the Czech Republic is said to be a figure of her. Historical references say she had a large head and long arms, a reference to her connection with spiders and spinning. Symbols associated with her include spindles and cloth, the rhombus (a nearly global reference to women's genitals for at least 20,000 years), and the Sacred Tree or Pillar.There are many goddesses in the various Indo-European pantheons who reference spiders and spinning. Historian Mary Kilbourne Matossian has pointed out that the Latin word for tissue "textere" means "to weave," and in several derivative languages such as Old French, "tissue" means "something woven." The act of spinning, suggests Matossian, is to create body tissue. The umbilical cord is the thread of life, transmitting moisture from the mother to the infant, twisted and coiled like the thread around a spindle. The final cloth of life is represented by the shroud or "winding sheet," wrapped around a corpse in a spiral, as thread loops around a spindle.

Our brief survey of agrarian holidays indicates that the peasant’s central concern is fertility and that special rites in the cemetery and/or rites involving a symbolic death & resurrection are a major component in these celebrations.

Belief in the absolute sanctity of “Mother Damp Earth” (Mat’syra zemlia) has been central to folk belief throughout the centuries. In remote areas, old people observed a ritual of asking the earth’s forgiveness prior to death into the 20th century. A number of scholars have maintained that peasants transferred attributes of earth worship to their particular veneration of Mary as “Mother of God.”

Fedotov: “At every step in studying Russian popular religion, one meets the constant longing for a great divine female power, be it embodied in the image of Mary or someone else. Is it too daring to hypothesize, on the basis of this religious propensity, the scattered elements of the cult of a Great Goddess who once...reigned upon the immense Russian plains?”

#Russian fairy tales#study blog#my notes#Slavic deities#slavic mythology#Russian paganism#russian folk belief

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint of the Day – 15 July – Saint Vladimir the Great of Kiev (c 956-1015) Grand Prince of Kiev and All Russia, Grandson of St Olga of Kiev, the first Russian ruler to embrace Christianity – born as Vladimir Svyatoslavich in 956 and died on 15 July 1015 at Berestova, near Kiev of natural causes. Patronages – converts, parents of large families, reformed and penitent murderers, Russia, Ukrainian Catholic Diocese of Stamford, Connecticut, Archeparch of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

440518-1

St Olga could not convert her son and successor, Sviatoslav, for he lived and died a pagan and brought up his son Vladimir as a pagan chieftain. Sviatoslav had two legitimate sons, Yaropolk and Oleg and a third son, Vladimir, borne him by his court favourite Olga Malusha. Shortly before his death (972) he bestowed the Grand Duchy of Kiev on Yaropolk and gave the land of the Drevlani (now Galicia) to Oleg. The ancient Russian capital of Novgorod threatened rebellion and, as both the princes refused to go thither, Sviatoslav bestowed its sovereignty upon the young Vladimir. Meanwhile, war broke out between Yaropolk and Oleg and the former conquered the Drevlanian territory and dethroned Oleg. When this news reached Vladimir he feared a like fate and fled to the Varangians (Variags) of Scandinavia for help, while Yaropolk conquered Novgorod and united all Russia under his sceptre.

A few years later Vladimir returned with a large force and retook Novgorod. Becoming bolder he waged war against his brother towards the south, took the city of Polotzk, slew its prince, Ragvald and married his daughter Ragnilda, the affianced bride of Yaropolk. Then he pressed on and besieged Kiev. Yaropolk fled to Rodno but could not hold out there and was finally slain upon his surrender to the victorious Vladimir; the latter thereupon, made himself ruler of Kiev and all Russia in 980.

As a heathen prince Vladimir had four wives besides Ragnilda and by them had ten sons and two daughters. Since the days of St Olga, Christianity, which was originally established among the eastern Slavs by Sts Cyril and Methodius, had been making secret progress throughout the land of Russ (now eastern Austria and Russia) and had begun to considerably alter the heathen ideas. It was a period similar to the era of the conversion of Constantine.

Notwithstanding this undercurrent of Christian ideas, Vladimir erected in Kiev many statues and shrines (trebishcha) to the Slavic heathen gods, Perun, Dazhdbog, Simorgl, Mokosh, Stribog and others. In 981 he subdued the Chervensk cities (now Galicia), in 983 he overcame the wild Yatviags on the shores of the Baltic Sea, in 985 he fought with the Bulgarians on the lower Volga and in 987 he planned a campaign against the Greco-Roman Empire, in the course of which he became interested in Christianity.

The Chronicle of Nestor relates that he sent envoys to the neighbouring countries for information concerning their religions. The envoys reported adversely regarding the Bulgarians who followed (Mohammedan), the Jews of Khazar and the Germans with their plain missionary Latin churches but they were delighted with the solemn Greek ritual of the Great Church (St Sophia) of Constantinople and reminded Vladimir that his grandmother, St Olga had embraced that Faith.

The next year (988) he besieged Kherson in the Crimea, a city within the borders of the eastern Roman Empire and finally took it by cutting off its water supply. He then sent envoys to Emperor Basil II at Constantinople to ask for his sister Anna in marriage, adding a threat to march on Constantinople in case of refusal. The emperor replied that a Christian might not marry a heathen but if Vladimir were a Christian Prince he would sanction the alliance. To this Vladimir replied, that he had already examined the doctrines of the Christians, was inclined towards them and was ready to be Baptised. Basil II sent this sister with a retinue of officials and clergy to Kherson and there Vladimir was Baptised, in the same year, by the Metropolitan Michael and took also the Baptismal name of Basil.

The Baptism of Saint Prince Vladimir, by Viktor Vasnetsov (1890)

A current legend relates that Vladimir had been stricken with blindness before the arrival of Anna and her retinue and had recovered his sight upon being Baptised. He then married Princess Anna and, thereafter, put away his pagan wives. He surrendered the city of Kherson to the Greeks and returned to Kiev in state with his bride.

When Vladimir returned to Kiev he took upon himself the conversion of his subjects. He ordered the statues of the gods to be thrown down, chopped to pieces and some of them burned; the chief god, Perun, was dragged through the mud and thrown into the River Dnieper. These acts impressed the people with the helplessness of their gods and when they were told that they should follow Vladimir’s example and become Christians, they were willingly Baptised, even wading into the river that they might the sooner be reached by the Priest for Baptism.

In 989 he erected the large Church of St Mary ever Virgin and in 996 the Church of the Transfiguration, both in the city of Kiev. He gave up his warlike career and devoted himself principally to the government of his people.

St Vladimir’s Cathedral

He established schools, introduced ecclesiastical courts and became known for his mildness and for his zeal in spreading the Christian faith. His wife died in 1011, having borne him two sons, Boris and Glib (also known as Sts Roman and David, from their Baptismal names).

Vladimir fell ill, most likely of old age and died at Berestove, near Kiev. The various parts of his dismembered body were distributed among his numerous sacred foundations and were venerated as relics.

During his Christian reign, Vladimir lived the teachings of the Bible through acts of charity. He would hand out food and drink to the less fortunate and made an effort to go out to the people who could not reach him. His work was based on the impulse to help one’s neighbours by sharing the burden of carrying their cross. He founded numerous churches, including the Cathedral of the Tithes (989), established schools, protected the poor and introduced ecclesiastical courts. He lived mostly at peace with his neighbours, the incursions of the Pechenegs alone disturbing his tranquillity.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Saint of the Day – 15 July – Saint Vladimir the Great of Kiev (c 956-1015) Saint of the Day - 15 July - Saint Vladimir the Great of Kiev (c 956-1015) Grand Prince of Kiev and All Russia, Grandson of St Olga of Kiev, the first Russian ruler to embrace Christianity - born as…

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mighty and Dreadful Chapter One: The Tower Where They Named Me

The wind hit the curl of the great stone fortress Praenuntius at a tackle, knocking its way against the towers of the School of the Raven. Witchers who hadn’t settled in yet or who were neither teaching nor on the Path were expected to stand at the watchtower. Tissaia tucked her face down into the thick fur of her hood and tried to focus her senses. The thick fog around the school protected it as much as it hid anyone approaching, but didn’t hide any scents. It was just a matter of catching them in the harsh air. She startled as Stribog came screeching out of the fog from where she’d sent him out on patrol. She lifted her arm to catch him. He shrilled at her, trembling with strain. Someone was coming and they weren’t a witcher. She wished – and not for the first time – that her raven could talk.

She darted across to the other side of the watchtower waving to Vea whose long braids were blowing like white ribbons in the wind. The lean witcher waved back, her raven Ilian launching out with an experienced wing to ride the curl of the wind around the tower before spinning down into the fog. From farther down the tower Tea’s raven Juna launched out swift as an arrow.

Tissaia curled a protective hand around Stribog, holding him close to her body. He shivered his beak clacking, his pearl-white eyes scanning out over the tower edge. From the fog came Ilian and Juna’s shrills. She waited, tense. There was the sound below of the front door opening. Tissaia let out two sharp whistles to be heard over the rush of air. On the second tower, Vea stood with her arm curled out to catch at Ilian’s experienced drift up through the wind and down into her arms. Breathless, Tissaia watched, then all at once, the suspense was broken. Vea, waved for her to sound the alarm. She lifted the trap door in the floor of the tower and dropped down, skipping the ladder, to pull the rope just as Grand Master Borch appeared dashing up the stairs. He had an expression on his face she had never seen before. He stood on the top stair for a moment before he gestured for her to follow him. Jackdaw clacked at her once from the Grand Master’s shoulder, but it was a tense sort of cut off sound.

“Sir?” she asked before she realized she was holding Stribog to her chest like she was still an acolyte and nudged him to take his place on her shoulder. She was fifteen, it was time she acted like it, in front of the Grand Master no less.

Borch smiled his kind gentle smile and motioned her along. “Come with me, Tissaia.”

They jogged down the halls because no one walked the halls of Praenuntius unless they were a baby or dying. Up ahead she heard one of the potion mistresses arguing with someone whose voice she didn’t recognize at all. There were very few men within the walls of the School of the Raven.

The potion mistress looked close to feral, her eyes dark and burning, her pale hair was bundled up on top of her head. “His body hasn’t been prepared, even without considering the fact he’s a boy or that he’s almost dead. If you’re that determined to bury your son just wait. You didn’t have to come here and drag an army with you!”

The other person looked like an elf, one she didn’t recognize, holding a bundled-up figure in his arms. He wore finer clothes then belonged in the Blue Mountains, marred with blood that looked half from himself and half from the person he held. “I know that your school uses forbidden magics. You would have the debt of me and of my people.”

“If we do this, and if he survives,” Grand Master Borch said. “He will never be able to father a child. Your line will end with him.”

The elf looked at Grand Master Borch, his expression broken down the middle. “Save my son. Please, old friend. You have to save him.”

The bells of Praenuntius began to ring out an alarm and raven calls suddenly sounded out of the halls of the school. Tissaia’s hands clenched into fists at her sides. She looked at Grand Master Borch. He looked calm, or perhaps just tired. It was just at the end of wintering in, the school was flush with witchers. Everything would be alright.

“We are going to have to improvise and be a little indirect,” Grand Master Borch told the potion mistress. “Tell Chireadan to prepare accordingly and have him pick one of the newer witchers he’s training, we can’t spare anyone at the gate.”

Tissaia didn’t understand what was happening.

Hand on the elf’s shoulder, Grand Master Borch led them to one of the raven roosts. They weren’t in there for very long before a giant raven landed heavy on the elf boy’s chest, making him cough and sputter up blood. “Cwa,” it said, dark and sarcastic and then sip at the red splatter around the boy’s side.

The elf looked on in horror, but Grand Master Borch just kept smiling. “Excellent. And off we go to the transformation chamber.”

The chamber was deep in the fortress, the only entrances into the cave underneath the Praenuntius and a long solemn hallway leading into it from the potion wing.

Before they went in, Grand Master Borch took the boy from the elf’s arms. “You can’t go any farther, I suggest you escape while you can or find a sword and join the fight.”

The elf pressed a kiss to his son’s forehead and ran off. Tissaia wasn’t paying him much attention, Stribog kept making concerned sounds in her ear.

Inside the transformation chamber Chireadan – the only other male witcher at the School of the Raven – was setting up his bottles and potions. He looked upset. Zola and Triss were there helping him set up with tubes and washing down the table.

“Grand Master Borch,” he said as he fiddled with the stand. “I feel as though I should protest. Boys don’t take the change as well and that boy hasn’t had anything to fatten him up, he hasn’t been trained. The transformation will tear him apart. You know what happens to acolytes who go through the change without being ready for it.”

“This is Filavandrel aén Fidháil of the House of Feleaorn,” Grand Master Borch said with that way he had of tipping his head back and then forward again. “He is the one who will take back Dol Blathanna if we fail from keeping it from falling, and save his people. For all our efforts it seems the time of sword and ax is nigh after all,” Grand Master Borch looked so sad. “We must keep him safe as long as we can.”

“His body has not been prepared,” Chireadan said again, voice grating like a poorly used whetstone. “He hasn’t even drunk any of the tea. The transformation is going to burn or drown him. He won’t be able to survive the Other, it will overtake him.”

“He is an exceptional child,” the Grand Master said. “Who will become an exceptional man. The survival of the elves rests on his shoulders. The weight of prophecy will have to be enough to help him survive. Our sacred charter is to save the world, have some hope Chireadan. Believe in a miracle.”

There was a sort of panic that blooming in Tissaia at his words, Stribog’s body pressed against the side of her head. They were all taught the prophecies from a young age. She’d been trained in waiting for the signs of frozen harbors, black suns, storks in Cintra, and the spilling of the blood of the elves. How the band that had founded the School of the Raven had prevented a new Conjunction of the Spheres only a few hundred years ago.

“I drank the tea,” a small lilting voice said from behind them.

Tissaia turned to look at a little acolyte, a boy, his arms full of clean sheets. His eyes were bright blue, and his brown hair as fine as dandelion fluff, his expression was so sweet and soft. Next to her she could feel the weight of the Grand Master’s stare.

“His papa loves him,” the little boy said, setting down the sheets on the transformation table to take up the elf child’s hand in his. “And he’s going to do good things. I want to help. I paid attention to Alta. I heard her say how you change us. The tea never made me sick like it did Dura or Mellie. I can help him get better and be with his papa again.”

Grand Master turned to Zola. “How has Julien been progressing, no trouble with the tea?”

“Like- like a fish to water,” Zola said, uncertain. She looked to Tissaia, but Tissaia didn’t know what to say.

Grand Master Borch held out his hand to the boy smiling with that soft kind smile, his eyes were so sad. “You’re a brave boy. That might be enough.”

Chireadan looked to her as he was preparing the bottles, pausing to do two sets instead of one. “You have near-perfect signs, don’t you? You caught lightning with Quen on your first try.”

“Yes sir,” she answered.

“Come stand near the boy. It will take too much to guide our elf friend here through the change, I need you to maintain Julian.”

“He prefers Jaskier,” Zola said from where she was helping Triss, her knuckles white around the bottles she was holding. “It’s what his mother called him.”

“I can’t,” Tissaia said. “I can’t do this.”

Grand Master Borch touched her shoulder and then cupped her face with his hands. “Look at me. Look at me.”

She blinked up at him. His eyes were such a perfect gold.

“Tissaia. You can do it and you will.” He made a sign against the side of her head, though she wasn’t sure which one it was, she felt a sudden assurance wrap around her. A total faith.

She nodded at him.

He pressed a hand to her shoulder, and then did the same for Zola, and Jaskier, and even Chireadan who wrapped his arms around Grand Master Borch and held on for long moments. “Be safe, old friend.”

“I have a few more tricks in me yet,” Borch told him, holding him tight. “I’m so proud of you Chireadan. I’m so proud. Thank you.”

And then Grand Master Borch was gone, closing the great doors behind him as he went.

The elf woke up then because of course he did. At least Chireadan was an elf, that seemed to calm him a little. “Where am I?”

“You’re at Praenuntius. The School of the Raven,” Chireadan said. “You’re dying and your father’s magic wasn’t enough to save you so you’re going to become a witcher.”

He could have lied a little.

“N-no,” the boy stuttered. “I’m an elf. Of the House of Feleaorn.” He began to cry, a soft almost silver sound. It was ridiculous. No one needed to cry that pretty. “They killed m-my mother. My brother. Athelinuin,” he said and covered his face with both hands. “He was going to teach me to play the lute and now he’s dead. Let me die. Please. I just want to be with family again. Let me die.”

Jaskier slid off the bed to go tuck the elf’s hand into both of his, holding it against his cheek. “You can do it. I know it’s hard. Grief is a river that finds it’s end in peace. Don’t let yourself drown in it,” Jaskier said. Tissaia had heard the same lesson from Alta who seemed to be repeating the philosophy to the new acolytes. “Don’t give up. No one is dead until they’re dead. Zola is really nice and Chireadan is really smart. They’re going to do something to save us and you and I are going to be alright. Please, don’t give up.” For all they were Alta’s words in Jaskier’s mouth, the boy had tuned them true to himself and played them well from his own lips.

A soft little crystal tear squeezed out of the elf’s eye, but he set his small jaw and nodded.

Zola scooted Jaskier’s cot closer so they could keep holding hands.

There was a cacophony of shrilling and shrieking from inside the fortress.

“Zola,” Chireadan said as he took the elf’s free arm, feeling with his fingertip for a vein. On the other side Triss did the same with Jaskier. “The door if you please.”

The curly-haired witcher barred the door and then centered herself. Her hands moved over the frame scratching in a combination of Yrden, Curn, and Quen before moving to the floor in front of it, layering in defenses.

“Tissaia,” Chireadan snapped at her.

She nodded back at him, centering herself. Stribog made a low rumbling sound from her shoulder.

“Listen to his heart, concentrate, focus your hearing like you were trained to on the hunt. You will need to use a sign combination of somne and quen to slow him down and maintain a low but constant rate. If his heart goes to fast the Trial will tear him apart, if it is too slow you will stop his heart and he will die.” He looked at her, smiling that same soft sad smile that Grand Master Borch used. “You can do this. Just listen to me, nice and slow. Begin with somne.”

She went into a kind of trance. Sign combinations were difficult, a sleight of hand that was almost magic. When the School of Raven had decided to go without mages, they had to make some adaptations. She could feel the sluggish beating of Jaskier’s heart going slower and slower under her hand, she could feel it reach the same pace as the little elf’s. Chireadan would give commands from time to time for the potions they used. She could feel when the first of it hit Jaskier’s system, the way his body shook with it. Sweat soaked down her forehead, down the back of her armor. The boy was so small, so terribly small even with all the fat packed on with an acolyte’s diet. Triss appeared at her side with a cloth and wiped her face off with swift movements. Her hands were cramping into hooks, her body screamed.

The majority of the School of the Raven were women. Only the witchers that specialized in the potions really knew the process, but there was something about the difference in it – the way the school went without mages – that meant women just took the change better. Jaskier must have been the only male acolyte. She vaguely remembered he was loud and had that too cheerful habit of trying to be helpful. Tissaia didn’t want to kill him. Chireadan made it look so easy. The turning of the Signs to the outer possible application. She didn’t remember anything more of her first transformation. She woke to blood on her sheets, went to go tell her bunk leader, and by the next morning her hair was white and she was a witcher. She hadn’t been awake for any of this, just woke up with a burning body and a world that was too loud.

“Second batch,” Chireadan said. She saw him move out of the corner of her eye and Triss moving to her right. Looking over she watched Triss pin Jaskier’s raven down onto it’s back with a practiced hand. The raven made a bit of an annoyed sound, but seemed too good-natured to fight the position. Then Triss took a branching tube with a sharpened edge in her hand and stabbed it into the raven’s chest.

Tissaia cried out and dropped Quen as Jaskier’s raven kicked and sprayed blood into the tubing. The raven struggled fiercely on the table – snapping and cawing, its feathers going out of place – but its blood was pouring out of it almost black in the tube and then grew weaker, and weaker, and then it just lay there making low croaks.

Kicking at Tissaia, Triss snapped her head in annoyance as she connected one branch of the tubing to some potion bottle that was connected to Jaskier. “Tissaia! Focus!”

All she could do was stare at Triss and down at the raven on the table. It was still, its eyes blank. Tissaia didn’t know what was happening.

“Tissaia! Focus or he’ll die!”

Turning back to Jaskier with a frantic sort of numbness, she cast Quen again. She felt it take, but weakly. She was losing control like a sled on a field of ice jack-knifing back and forth. She didn’t know. She didn’t know they killed the ravens. Stribog was on the cot staring at the twitching body of Jaskier’s pretty raven. His eyes were white. All the witchers had ravens with white eyes.

Jaskier made a high pained animal sound twitching and writhing so hard he would have thrown himself off the bed if Triss hadn’t been there to throw her body on top of him. What were they doing? What had been done to her?

“Tissaia!” Triss screamed. “He needs you!”

She couldn’t get it to stop, she couldn’t get control back. She hissed out from between her teeth. Her fingers felt like they were being torn to pieces. She was going to do this, she could do this! The first level of protection on the door activated in a swirl of color. How far had the enemy breached to get to the turning room? She felt her Other rise up, tight-laced to the throat and absolutely full of teeth.

“I could have been a mage!” Tissaia howled, she could feel the sort of red mist of going feral circle around her vision. She wanted to bite, she wanted to tear. “I could have been a mage. The greatest who ever lived. I chose what I am. I chose this, I chose to be a wonder and a horror! I am the rage in the night! I am the silver sword and the fist of steel! I am powerful and you will obey me!”

Jaskier dropped down so still she thought she had killed him, but no there was the soft murmur of his heart in her hands. She felt something wet on her mouth and droplets of blood landed on Jaskier’s face where she leaned over him. She felt odd and light-headed.

“Third potion, Triss,” Chireadan said. “Now.”

“It’s only been a couple of hours. It’s too soon,” Triss said, still crouched over Jaskier’s body.

There was a bang at the door and the Quen shivered all over like an angry cat.

“Do as I say Triss.”

The fear coming off Triss sent dread like a claw from the tip of Tissaia’s head to the small of her back.

“Third potion,” Triss said.

There was another bang at the door.

“Zola,” Chireadan said. “Get my swords and lean them against the table and go open the back door to the caves, please.”

Something black was seeping out of Jaskier’s nose, Triss tilted the boy to the side and it came out of his mouth as well. She switched the tubing going into Jaskier’s raven, it began to make feeble jerking motions.

“He’s too young,” Triss said. “His body isn’t taking it.”

“He’ll be fine,” Chireadan told her, he swayed on his feet, but his hands never faltered. “Have some faith.”

The bang came at the door again, something odd in the sound and Quen shattered.

“They have a mage,” Zola said.

“Triss, be a dear and pack everything up,” Chireadan said, voice showing a bit of strain. “Destroy whatever you can’t carry. All of you are going to leave and find shelter elsewhere. Do not return here for a few years. Do not wait for anyone, do not tell anyone where you are from or where you are going. Act as if you were the last of the School of the Raven. Winter in at Oxenfurt, we have friends there. Do not tell anyone that the school was under attack. Do not tell anyone about the transformation process.”

Triss moved around in her periphery vision almost at a blur, there were flashes of heat and the pop of breaking glass bottles. Tissaia watched Jaskier’s hair turn white. He kept jerking in place. The elf boy wasn’t jerking in place. She was doing something wrong, she had to be doing something wrong.

“It’s as done as it’s going to be,” Chireadan said. Tissaia released Quin and her hands instantly cramped up into fists. Triss came up behind her and helped her put on a pack and swords, then pulled up her hood for her. Jaskier’s raven twisted up onto its feet, its eyes were white, it was staring at Jaskier’s face, the smear of black around his mouth and nose. “Triss,” he said. “Be a dear and finish this up, will you?” He started muttering to himself in Elder as he pulled out cat potion and drank it down. He was bouncing on his feet in a way Tissaia associated with going a bit feral, his head swinging back and forth.

“Yes, sir,” Triss said. She yanked the tubes out of everyone, wrapped Jaskier and Filavandrel in their sheets like they were shrouds and put the elf in Zola’s arms. “Come on, Zola,” she said. “We need you.”

“But-” Zola started, the door was bowing.

“Don’t be selfish,” Triss snapped at her. “Chireadan told us to go.” She picked up the little acolyte, his pretty white-eyed raven fluttering awkwardly over to perch on the boy’s chest.

The caves under the school weren’t properly underneath it. There was a tunnel covered in the glowing moss that was one ingredient in the tea they drank and cold stone steps going down, down, down. Chireadan looked at her, smiled at her and then closed the secret passage door behind them. There was a scrape on the other side of the door as though something was being moved in front of it.

She. She felt.

She turned and followed after the other witchers, hating the vulnerability of how her hands were all knotted up. She couldn’t even hold a sword like this. The stairs turned into finally into a kidney-shaped room. There was the partially frozen over pond where the acolyte fish waited to be caught and the hole where little acolytes were tossed in to learn to get out of ice that had cracked or to become food for the fishes in turn. Alta had trained acolytes for at least a hundred years since she lost her leg. The trainer was a blocky woman who kept her hair short and had always been honest with them. Let the cold polish away weaknesses, learn the edge’s of endurance, become hard and self-sufficient.

She pushed forward, mindful of the ice over the pond. She didn’t have her cleats, but she had been running on snow and ice as long as she could remember. They walked together, out into the open white of the frozen valley. The stink of chaos was heavy in the air as poison in the air. Ahead of her Jaskier was shaking in Triss’ arms, his body jerking in a way that didn’t seem like the cold. She wanted to ask if he was dying, but her mouth stayed stubbornly closed. Behind her she could hear shouting and smell blood. Stribog landed like a stone on her shoulder, clacking at her for a moment before taking off ahead.

Tissaia looked back over her shoulder at the tower, at the screaming cloud of ravens dispersing. Fire blossomed at the front of the tower, an immense wave of Axii that made her eyes sting to look at it. This had been her home for a decade, the massive dark stalactites reaching for a sky that would never reach back. Black towers smooth as obsidian glass with ice piled up like diamonds standing tall on a massive lake of ice. She knew that chance had rescued her, she knew from the death cries of the ravens that witchers were dying – witchers better than her. Still, she could not do the sensible thing and go. Her whole vision was those black towers that had always been warm, full of companionship, a place where she was thought to be more than grief and a temper. A place where she had been taught the coming of the end of the world and how to delay it, delay it, delay it until it was in inconvenience, not a cataclysm.

Zola took her by the arm of her coat and shook her. “We have to go. The kids can’t take prolonged exposure.”

She looked at Zola. Her golden eyes were kind and warm and terrified. Tissaia set her jaw and nodded. She was a witcher. She was strong.

#Mighty and Dreadful#long post#let's hear it for the b team#the witcher#the witcher au#tissaia#reverse witcher#witcher fanfic#cross posting on tumblr because I do what I want#4000+ words

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay poll time bc i’m struggling to figure out viktor’s pjo verse my options for him rn aaaaare--

1. greek demigod, son of nike ( greek goddess of victory ) 2. slavic demigod, son of stribog ( slavic god of the sky/wind )

#ooc post !#help#i figure if there can be norse demigods there can be others too right? but i can't decide#IM 1-800-STRUGGLING

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, Sam! Happy STS!

Who would be your OC(s)'s godly parent? Feel free to pull from any pantheon you'd like!

Hi Tori! Thank you for the question

I'd love to go with the Slavic gods, because it would be so on brand for the Sunblessed Realm. Alas, given the scarcity of written sources, these deities aren't that well defined, and often overlapping, so I'm slightly going by the vibes I get from them.

Lissan - Dazhbog. That's a sun deity, vaguely equivalent to Helios, and Lissan is sun-coded in the 'burning brightly and unstoppably ' sort of way, but is also associated with prosperity and well-being, which is Lissan's goal.

Ianim - Rod. God of family, ancestors, and fate. Ianim feels very much bound by family obligations and is anxious about living up to his family's expectations. But also, there's the fate vs. free choice aspect to his arc.

Gullin - Stribog. It's a wind deity, and Gullin's superpower is related to wind. Wind has also been referred to as 'son of Stribog' in at least one source that I've seen. But also Zeus. And not because of the weather aspect.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you consider Svarog to be a phantom deity ? I think there is only one source that mentions him ( correct me if I’m wrong) and I’ve heard people say that he was created as a Slavic version of the Greek god Hephaestus. I don’t have any source for this but it is something I’ve heard some people say.

Hello!

That’s right, there’s only one source that mentions Svarog. However he wasn’t necessarily created as a Slavic version of Hephaestus, the story is a little more complicated than that.

In the entry for year 1114 of the Tale of Bygone Years the author includes a translated fragment of a Byzantine chronicle with a glossa that equates Hephaestus to Svarog and Helios to Daždbog. The Byzantine chronicle in question was originally writen in Greek by John Malalas, who was in turn drawing heavily from 3rd century BC „Egyptian History” by Manetho. In Malalas’ text names of Egyptian deities were replaced by the Greek gods viewed as their counterparts, so Ptah became Hephaestus and Ra became Helios. It’s believed that the glossa adjusted the names one more time, in the same fashion, so that they resonate with local readers. And thus we came to view Svarog as the god of fire and smithing similar to Hephaestus and Daždbog as the god of the sun akin to Helios.

We don’t actually know if the glossa was contributed by the translator of the Byzantine text into Slavonic (who was most likely Bulgarian according to Gieysztor) or by the author of the Tale of Bygone Years. So we don’t know in what year or in which region it was created either and we can’t say much about how familiar the writer was with pagan customs of Rus. It’s very likely that the author was a Christian monk.

Dažbog appears in the Tale of Bygone Years a few more times, most notably in an earlier entry for year 980 where he is mentioned as part of kniaz’ Volodymyr’s state pantheon of pagan gods.