#Siyi region

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Taishan Translation Service: Cantonese vs Taishanese Language Variations

The Untold Story of Taishanese Influence in America’s Chinatowns Taishanese, a lesser-known dialect of the Chinese language, has played a pivotal role in shaping the language and culture of Chinatowns across North America. This article delves into the fascinating history and significance of this linguistic gem, shedding light on its impact on the Chinese-American community and the importance of…

View On WordPress

#Chinatowns#Chinese-American community#Cultural Heritage#Guangdong Province#language translation services#LanguageXS#Linguistic Diversity#North America#Siyi region#Taishanese language

0 notes

Text

The Creation of Immortals 1 (2018) 封仙册之铁扇罗刹

Director: Liu Baoxian Screenwriter: Zhu Na Starring: Lin Siyi / King Kong Genre: Comedy / Romance / Costume Country/Region of Production: Mainland China Language: Mandarin Chinese Type: Retelling

Summary:

"The Iron Fan Rakshasa in the Book of Immortals" is produced by Hua Vision (Xiamen) Film and Television Culture Co., Ltd. Sun Wukong broke the alchemy furnace of Taishang Laojun, and the fragments fell into the country of Qiuci, forming the Flame Mountain. Not only did it bring an everlasting mountain fire, but it also unintentionally opened the demon seal, and the demon king's "inner demon" took advantage of the chaos to sneak into the world. Princess Meiyue is a demon-hunter. In order to get rid of Princess Meiyue, the inner demons designed to force out her third-life personality, making her insane and blaming her for the murder of the king. Princess Meiyue defeated her inner demons with the help of her first life partner Yuan Buxie.

Source: https://chinesemov.com/2018/The-Creation-of-Immortals-1

Link: https://www.nunuyy5.org/dianying/99014.html

#jttw media#movie#jttw movie#live action#retelling#addition#princess iron fan#demon bull king#bull family centered#sun wukong#dragon king of the east sea#Inner Demon#封仙册之铁扇罗刹#The Creation of Immortals 1

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

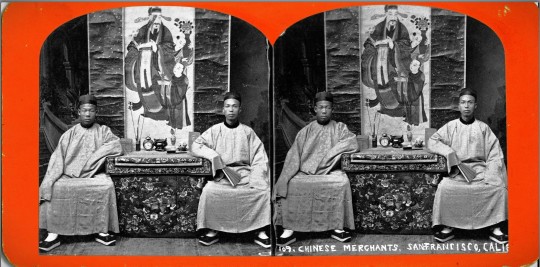

“109. Chinese Merchants, San Francisco, Calif.” c. 1890 – 1899? Stereograph by Nesemann Woods Gallery, Marysville CA (from the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection of the University of British Columbia Library).

Merchants of Old Chinatown

In the late 1840s and the 1850s, Chinese merchants and traders made their initial foray into California. By February 1849, the number of Chinese had increased to 54 and by January 1850, historians would count 787 men and two women in San Francisco. In December 1849, the Alta California newspaper reported that 300 Chinese convened a meeting at the Canton Restaurant on Jackson Street for the purpose of organizing the “Chinese residents of San Francisco” and engaging the services of lawyer Selim E. Woodsworth to “act in the capacity and adviser for them.”

In his book, Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown, historian John Tchen wrote about the vanguard of old San Francisco Chinatown’s merchant elite as follows:

“These pioneers hailed primarily from the Sanyi (Saam Yap) or Three Districts [三邑], as well as the Zhongshan area in the immediate vicinity of Canton. It's important to note that Nanhai (Namhoi) and Panyu (Punyu) stood out as the most prosperous districts within Guangdong Province. Their economic pursuits ran the gamut from cultivating fertile agricultural lands, breeding silkworms and fish, to crafting silk textiles, producing ceramics for both domestic and international markets, and engaging in various other commercial endeavors. “What set apart the merchants and artisans from Sanyi and Zhongshan was their mastery of a more refined city dialect compared to their Siyi (Sei Yap) counterparts, who mainly consisted of poorer, rural communities. Remarkably, over 80 percent of Chinese immigrants in North America originated from the Siyi [四邑] region. A noteworthy portion of these Sanyi merchants belonged to the emerging class of compradores, individuals who facilitated business transactions on behalf of Western trading companies. These California-based Sanyi merchants thus brought prior experience in dealings with Western entrepreneurs, and California was seen as a promising arena to expand these lucrative connections.”

With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May of 1869, the more sophisticated and adventurous members of San Francisco’s pioneer Chinese merchant community would begin exploring other cities in the United States in search of opportunity.

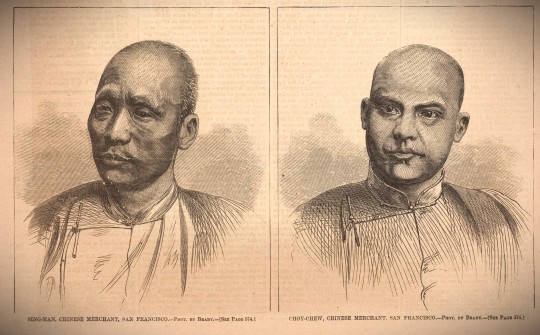

“Sing-Man, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco” and “Choy-Chew, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco,” Harper’s Weekly, September 4, 1869, wood engraving on paper. Artist unknown, artist after a photograph by Mathew Brady, 1869 (from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery).

For example, in the Harper’s Weekly article (Sept 4, 1869, page 574), the reporter identified merchant Choy Chew as a San Franciscan and a talented linguist of sufficient intellect and stature to be invited to give a speech at a European-American banquet. He reportedly visited Chicago with a fellow merchant, Sing Man, before traveling to New York where the pair were regarded as “representatives of Chinese industry and commerce.”

At the banquet in Chicago, Choy Chew delivered the following remarks:

”Eleven years ago I came from my home to seek my fortune in your great Republic. I landed on the golden shore of California, utterly ignorant of your language, unknown to any of your people, a stranger to your customs and laws, and in the minds of some an intruder — one of that race whose presence is deemed a positive injury to the public prosperity. But gentlemen, I found both kindness and justice. I found that above the prejudice that had been formed against us, that the hand of friendship was extended to the people of every nation, and that even Chinamen must live, be happy, successful and respected in ‘free America.’ I gathered knowledge in your public schools; I learned to speak as you do; and, gentlemen, I rejoice that it is so; that I have been able to cross this vast continent without the aid of an interpreter; that here in the heart of the United States I can speak to you in your own familiar speech, and tell you how much, how very much, I appreciate your hospitality; how grateful I feel for the privileges and advantages I have enjoyed in your glorious country; and how earnestly I hope that your example of enterprise, energy, vitality, and national generosity may be seen and understood, as I see and understand it, by our Government … ”We trust our visit, gentlemen, may be productive of good results to all of us; that the two great countries, East and West, China and America, may be found forever together in friendship, and that a Chinaman in America, or an American in China, may find like protection and like consideration in their search for happiness and wealth.“ -- from the Scientific American, new series, vol. 21, no. 9, p. 131 (August 28, 1869)

The founding in 1888 of the Merchants’ Exchange in old San Francisco Chinatown represented the logical culmination of several decades of robust business operations by the pioneer Chinese merchants in the city and beyond.

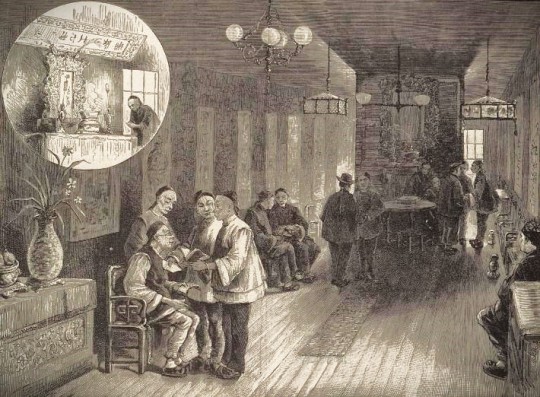

“Chinese Merchants’ Exchange, San Francisco.” Lithograph from Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 26, March 18, 1882 (from the collection of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In his book, A Guide Book to San Francisco (published by The Bancroft Company in 1888), John S. Hittell described the Chinese Merchants Exchange as follows:

“At 739 Sacramento Street are the new rooms of the Chinese Merchants' Exchange. They are fitted up in the ordinary Chinese style, and though presenting no special attraction to the visitor, the business transacted there is of considerable importance. A Chinese merchant, contractor, or speculator never starts on any enterprise alone. He always has at least one partner, and in most cases several. He makes no secret of his transactions, but converses about them at the exchange, and often goes there in search of capital when his own means are insufficient. He sometimes applies to that institution to find him a capable man to manage a new business which he is about to start. If, as often happens, one be selected who is in debt to other members, they make arrangements which will not interfere with the new enterprise; and the debtor is not unfrequently released from his obligations.”

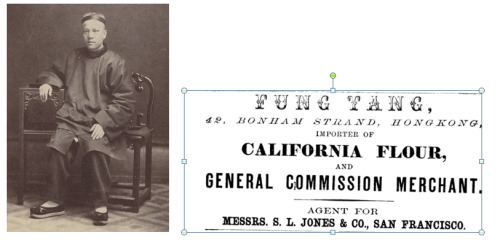

Fung Tang

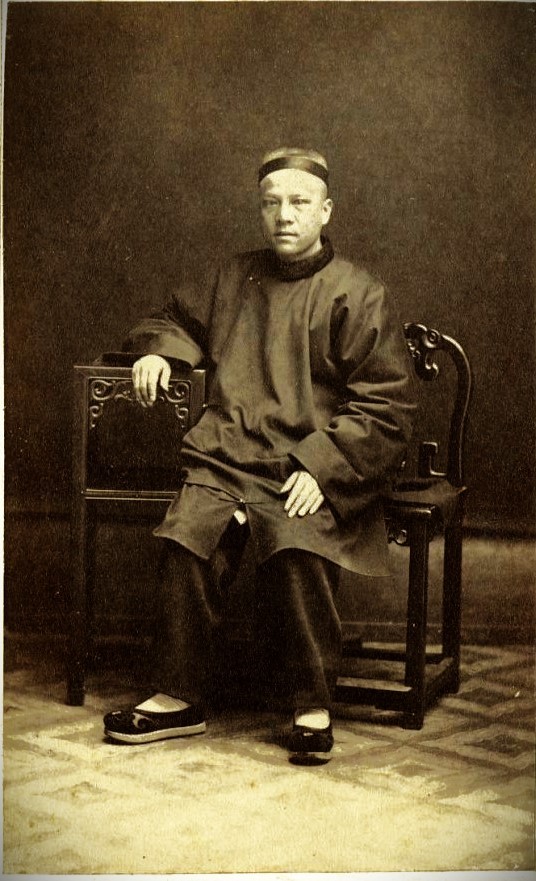

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

The address of the Merchants’ Exchange at 739 Sacramento Street was hardly surprising, as it shared the same building which had housed the mercantile house of a legendary merchant, Fung Tang. Historian York Lo, in his article for The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website, described Fung as “a native of Jiujiang (Kow Kong) in the Nanhai county (南海九江) in Guangdong, Fung Tang followed his uncle Fung Yuen-sau (馮元秀) to California in 1857 at the age of 17 and worked at Tuck Chong & Co (德祥號辦莊), a trading business founded by his uncle and his fellow Nanhai native Kwan Chak-yuen (關澤元).” In the Langley San Francisco directory of 1868, the Tuck Chong & Co. is listed as “(Chinese) merchants” located on Chinatown’s first main street at 739 Sacramento Street.

“In his spare time,” York Lo writes, “he learned English from Reverend William Speer and became fluent in the language. With his linguistic skills, he became a bridge between the Chinese and the white community in San Francisco and even befriended Peter Burnett, the first Governor of California, who described Fung in his memoir as ’a cultivated man, well read in the history of the world, spoke four or five different languages fluently including English, and was a most agreeable gentleman, of easy and pleasing manners’.”

As such, Fung Tang must be considered as a logical client for the pioneer Chinatown photographer, Kai Suck. A professional studio portrait would have conferred respectability in the eyes of the non-Chinese businessmen and politicians with whom he interacted. In fact, Fung appears to have deployed the same portrait now reposing in the collection of the California Historical Society as part of his commercial advertising in Hong Kong.

An advertisement for Fung Tang’s flour import business in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong.

For more details about Fung’s business exploits and his public service, including his election to the board of directors of the Tung Wah clinic (the original predecessor organization of the future Chinese Hospital), readers are encouraged to read York Lo’s piece here: https://industrialhistoryhk.org/fung-tang-the-firm-the-family-the-transpacific-metals-trade-and-tin-refinery/?fbclid=IwAR3DU6pEcaEw6w2uH1OZvFBFL8vg-Rl4keBS-VkbcttFuHKlx973g3ZjcY8

Tchen asserts that the influx of British and other Western imperialist powers into China’s major treaty ports transformed the status of merchants engaged with Western trading companies. Rather than operating on the margins of Qing-era society, the merchants gained unprecedented prestige and influence. Beyond China's borders, they experienced far more freedom to engage in trade and amass substantial profits without the worry of state-imposed restrictions. They rapidly acquired the necessary language skills and business acumen to navigate their newfound opportunities.

San Francisco’s early Chinese merchants swiftly grasped the English language and American business practices, excelling in American-style transactions, and developing strategies for fostering positive relations with the general San Francisco populace. The local press affectionately labeled them "China Boys." They made conscious efforts to participate in the celebrations of significant American holidays, further endearing themselves to the San Francisco community.

This approach significantly bolstered their rapport with the local population, as evidenced by the California Courier's glowing praise: “We have never seen a finer-looking body of men collected together in San Francisco. In fact, this portion of our population is a pattern for sobriety, order, and obedience to laws, not only to other foreign residents, but to Americans themselves," declared Cornelius B. S. Gibbs, a marine-insurance adjuster, in 1877. Gibbs emphasized the high esteem in which Chinese merchants were held among white business circles. “As men of business, I consider that the Chinese merchants are fully equal to our merchants. As men of integrity, I have never met a more honorable, high-minded, correct, and truthful set of men than the Chinese merchants of our city.”

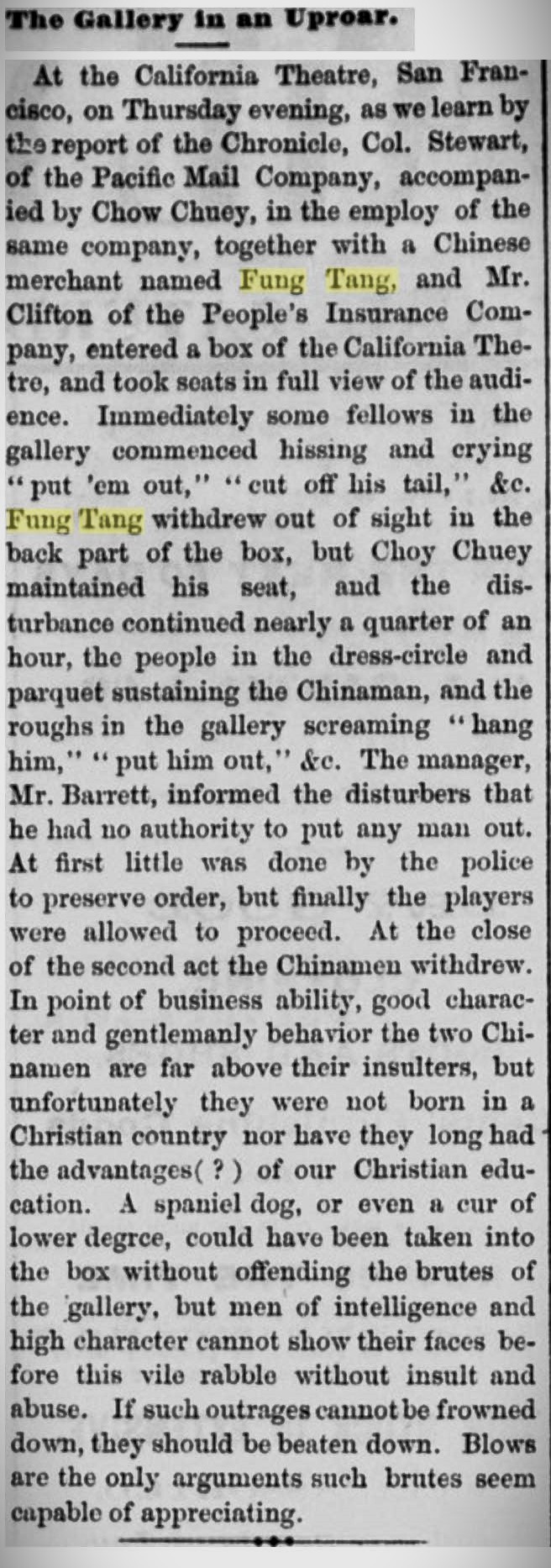

Attempts to participate in mainstream society, however, were not always welcomed by lower-class elements of white society as evident in this news account about Fung Tang’s appearance in San Francisco’s California Theatre in September 1869:

Clipping from the San Jose Mercury News, September 18, 1869 (vol. I no. 42)

Fung Tang’s transpacific success in San Francisco was hardly unique among the ranks of Chinatown’s early merchant class. He exemplified the business acumen of his fellow pioneering entrepreneurs and their establishment of transpacific trading posts in strategic locations.

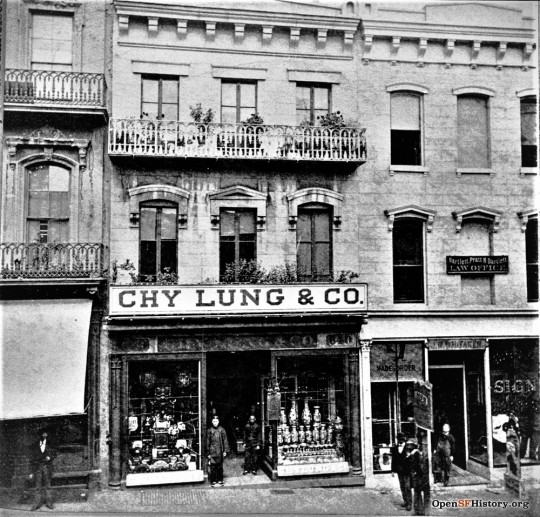

Lai Chun-chuen and Chy Lung Co.

The story of the pioneer business of Chy Lung & Co. predates the history of San Francisco Chinatown itself, and its establishment spurred the rise of Chinatown’s first commercial strip, Sacramento Street (唐人街; canto: “Tohng Yahn Gaai”) or “Chinese Street.”

An enlargement of the stereograph taken by Carleton Watkins for the Thomas Houseworth & Co., and “[e]ntered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866 by Lawrence & Houseworth, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the Northern District of California.”

“Among the early Chinese settlers were merchants like Lai Chu[sic]-chuen,” the late historian Judy Yung wrote in her pictorial book, San Francisco’s Chinatown (published by the Chinese Historical Society of America). “Upon arrival in 1850, he opened Chinatown’s first Bazaar at 640 Sacramento Street, importing teas, opium, silk, lacquered goods, and Chinese groceries.”

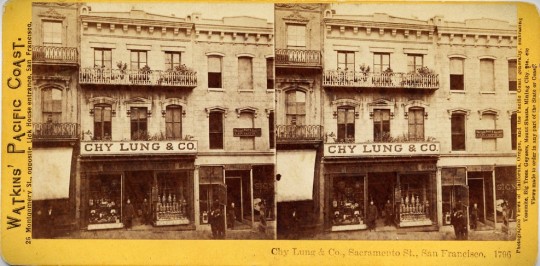

"Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento St., San Francisco. 1796" c. 1866. Photograph by Carleton Watkins for his Watkins' Pacific Coast stereograph series (from a private collection).

Chy Lung’s founder, Lai Chun-chuen (a.k.a. Chung Lock), came to San Francisco in 1850 from Nam Hoi county. According to UC professor Yong Chen, the business founded by Lai and, his partners Xie Mingli, Fang Ren, Sheng Wen, and Chen Nu, appear in the earliest business directories for San Francisco. A “Chyling, china mer, 188 Washington” appears in the Parker directory for 1852-1853. The Colville’s directory of 1856 lists a “Chy Lung (Chinese) mcht, Canton Silk and Shawl Store, 166 Wash’n,” and the business would remain on Washington Street (moving to 612 Washington St. by 1858) until 1863 when it relocated to 642 Sacramento Street. By 1865, the Chy Lung & Co. had either expanded or taken over the address of 640 Sacramento Street.

Portion of the stereograph “No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co.,” c. 1866. Published by Lawrence & Houseworth (from in the collections of the Society of California Pioneers, Wells Fargo Corporate Archives, and the Library of Congress).

“He imported Chinese prefabricated houses and cargoes of Chinese goods, teas, silk, lacquer and Porcelain wears, and even opium,” historian Phil Choy wrote. “The drug that made American merchants millionaires in the China trade now found its way to California for both the Chinese and American markets Chy Lung was one of only two Chinese businesses at the time that advertised in an American newspaper, the Daily Alta California.”

“No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento Street.” c. 1866. Published by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from in the collection of the New York Public Library).

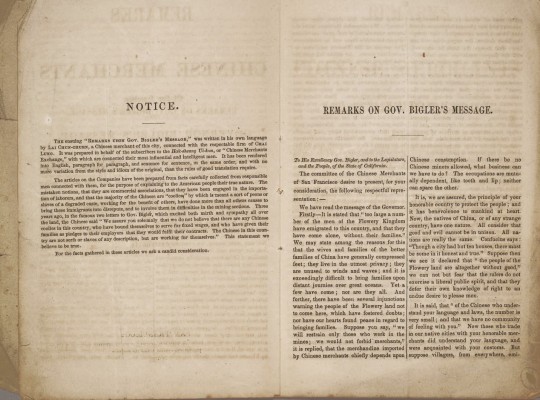

Lai Chun-chuen is remembered not only for his business acumen but also as the principal author of the objections to the anti-Chinese movement in California and plea for civil rights as published in the pamphlet, Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco, upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections (San Francisco: Whitton, Towne, 1855).

The preface to Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections of 1855 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The second line of the first paragraph identifies Lai Chun-chuen as “a Chinese merchant of this city, connected with the respectable firm of CHAI LUNG.”

Chy Lung & Co. continued to play a leading role in the Chinese merchants exchange until Lai Chun-chuen’s death on August 30, 1868. The business remained a fixture of the Chinatown business community for the rest of the 19th century, and it adopted the new communications technology of the telephone, as shown by the Pacific Telephone directory for the Chinese Exchange in 1902.

The listing for Chy Lung & Co. as it appeared in the Wells Fargo directories of Chinese business for 1878 and 1882.

The Chy Lung & Co. business, and others established by Chinatown's merchants, soon comprised a source of both tangible and symbolic power within the rapidly growing Chinese community in the American West. As the Chinese immigrant population swelled, businesses catering to their specific needs diversified and expanded. A hierarchical structure emerged, influenced by both economic factors and the district of origin. The wealthier Sanyi individuals typically presided over larger, commercially successful enterprises, including import-export firms. Those from the Nanhai District dominated the men's clothing and tailoring sector, as well as butcher shops. The neighboring Shunde District populace exercised control over overalls and workers' clothing factories.

“S.F. Chinatown 1898 C12”. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Collection of the San Francisco Public Library). A well-attired merchant and possibly his son walk south on Spofford Alley from Washington to Clay Street.

Meanwhile, Chinese hailing from the Zhongshan District, which represented the second-largest Chinese population in California, were prominent in the fish and fruit orchard businesses, as well as in the production of women's garments, shirts, and underwear.

"Quan Quick Wah"

“Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). A descendant of the large, confident man shown in traditional robes identifies him as San Francisco merchant “Quan Quick Wah.” Based on other photographs of this Chinatown location, the pair appears to be walking on the west side of Waverly Place toward its intersection with Clay Street. In his book about Genthe’s Chinatown photographs, historian Jack Tchen wrote about this imposing figure followed by a bodyguard as follows: “The powerfully built man dressed in traditional silk robes has been described as a tong leader. Whether he was a tong leader, a wealthy merchant, or both, his dress and carriage convey a strong presence. Tong leaders came to rival the power of wealthy merchants. The man following the merchant or tong leader is said to have been his bodyguard, protecting him from the attack of a rival tong. In the photograph the two are passing under ornate cloth lanterns that indicate a pawnshop business.”

"Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). This full photograph in the Library of Congress shows that Genthe’s image fortunately included a portion of the sign for the entrance to a basement restaurant. The signage (which appears in other photographs of this area), indicates that the merchant and bodyguard were photographed walking on the west side of Waverly Place (at about no. 23 and 25 Waverly) and toward the southwest corner of its intersection with Clay Street. Tchen’s guess that the background store frontage was a pawnshop is probably correct, as the “Qung Hing Art Co.” pawnshop occupied space at 25 Waverly during the 1890s. The headquarters of the merchant-controlled, Ning Yung district association was located at 23 Waverly.

Yee Ah-Tye

In old Chinatown, merchants’ personal use of bodyguards or alliances with fighting tongs were common. The organization and fragmentation of district and clan associations, along with sharp business competition, often placed lives, as well as livelihoods, at risk. For example, the Kong Chow association traced its origin to about 1853, when the influential community leader, Yee Ahtye (a.k.a. “George Athei”) persuaded members of his Yee clan of Sunning, which had remained in the Sze Yup Co. (after a number of clans split off to organize today’s dominant Ning Yung Association), to finally secede. The action by the Yee clan was joined by clans from Hoiping and Enping counties after a dispute over the presidency of the Sze Yup Co. in 1862. The resulting new association, the Hop Wo, soon challenged the merchant Ah-Tye for the custody of a piece of land on which Ah-Tye had allowed the Sze Yup Association to build a headquarters building. Yee eventually deeded the land to a new Kong Chow Association, which his fellow Sunwui merchants founded in 1866. The dispute over this property raised to such a level that Yee and his associates were compelled to organize a secret society, the Suey Sing Tong, to protect the asset and enforce his decision.

Portrait of Yee Ah-Tye (courtesy of the Chinese Six Companies). Yee was an elite merchant of Chinatown and was considered a co-founder of the Suey Sing Tong.

Born around 1829 in Guangdong province, Yee Ah-Tye had arrived in San Francisco just before the gold rush at around 20 years old. In spite of his humble beginnings, Yee had learned English in Hong Kong and swiftly ascended to a position of authority within the influential Sze Yup [pinyin: "Siyi"] Association. The Sze Yup Association, along with similar Chinese district associations, played a crucial role in assisting newly arrived Chinese immigrants during the 19th century. The organizations provided accommodation and job opportunities.

Aside from his many business accomplishments, Yee famously cross paths with the legendary, San Francisco madam Ah Toy. The conflict arose when Ah Toy accused Yee of demanding a tax from her prostitutes on Dupont Street. Despite her origins in China, Ah Toy had by then lived in America for three years and become familiar with its legal system. She boldly threatened to take legal action against him, a move she would not have dared to undertake in China.

The August 1852 report in the Daily Alta California newspaper highlighted Ah Toy's shrewdness, emphasizing her knowledge of living in America and her ability to navigate the legal system. She resided close to the police station, fully aware of where to seek protection, having faced legal proceedings herself numerous times. The reporter gleefully suggested that Yee use caution about overstepping his authority, warning that he might lose his dignity and end up in custody.

A year later, Yee faced legal trouble himself, being arrested for assault and grand larceny. The San Francisco Herald alleged Yee “inflicted severe corporeal punishment upon many of his more humble countrymen … cutting off their ears, flogging them and keeping them chained for hours together.”

After moving to Sacramento in 1854, Yee also relocated his business activities in 1860 to La Porte, California, where hydraulic and drift mining operations for gold occurred. Yee acquired a partnership in a store called Hop Sing & Company which supplied merchandise and Chinese contract laborers. By 1866, it was the richest Chinese store in that town, with a value of $1,500 (about $36,000 in 2005 dollars).

According to one of his descendants, Lani Ah Tye Farkas, the pioneer Yee Ah Tye reportedly lived thirty-four years in La Porte as a successful merchant, running the Hop Sing and Company store and representing the Chinese community in the area. He had three wives and four children, three of whom were girls. Unlike most other Chinese fathers at the time, he invested in the education of his daughters – he even bought a piano for his youngest daughter, Bessie, who became an accomplished pianist. As a leader in the Hop Sing Association, he founded a small hospital to serve the elderly Chinese men of La Porte.

“The temple ruins at San Francisco's Lincoln Municipal Park Golf Course was once part of the Lone Mountain Cemetery, a gift of Ah Tye,” Lani Ah Tye Farkas wrote in 2000. “Other glimpses of his life in America can be seen in deeds, mining claims, tax assessments, newspaper articles, and land that he once owned. Yee Ah Tye's legacy, however, is in his descendants. Many Chinese with common last names like Chan, Lee, and Wong may have no relationship with one another. However, the descendants of Yee Ah Tye have borne his unique last name through six generations, in the words of the Yee family genealogy, ‘spreading like melon vines, increasing continuously’” Yee died in 1896. (see: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/pc289j76z)

Contract Labor

At the lower end of the business hierarchy, the Siyi or Four District residents comprised the largest and least affluent group of Chinese immigrants. They typically occupied occupations such as laundries, small retail shops, and restaurants and the bulk of the laborers in the contract labor system.

In the period preceding the Civil War, there was a concerted effort by certain individuals to introduce contract laborers into the United States. A letter penned by C. V. Gillespie to Thomas Larkin on March 6, 1848, sheds light on this initiative. Gillespie expressed a keen interest in the idea of bringing Chinese emigrants to the country, suggesting that a variety of skilled workers and laborers could be sourced:

"One of my favorite subjects or projects is to introduce Chinese emigrants into this country,… Any number of mechanics, agriculturists and servants can be obtained. They would be willing to sell their services for a certain period to pay their passage across the Pacific…."

The practice of importing contract laborers to the United States began in the late 1840s and continued through the 1850s. However, enforcing labor contracts proved to be a challenging endeavor on American soil. A case in point involved an Englishman who, upon bringing fifteen Chinese laborers to the country bound by a two-year contract, found that they immediately reneged on their agreement upon arrival. Authorities, at the time, were reluctant to intervene in such disputes.

In 1852, Senator George B. Tingley introduced a bill in the California State legislature aimed at legalizing and facilitating the enforcement of contracts allowing Chinese laborers to sell their services to employers for periods of up to ten years at fixed wages. This proposal, however, faced significant public backlash and was ultimately defeated after a heated debate. The subsequent year saw members of Chinese companies admitting that they had initially imported workers during the early years of the Gold Rush. Yet, due to unprofitability and difficulties in enforcing labor contracts, they abandoned this practice.

“San Francisco Chinese Merchant” no date. Photographer unknown, possibly by Ann Ting Gock (from a private collection). This rare and unusual image suggests that the individual might not have been a mere merchant at all, but a member of the Chinese consular staff. He is seen wearing his 清代官帽 (canto: "ching dai gwun moe") or official's headwear. The Qing official headwear or Qingdai guanmao (Chinese: 清代官帽; pinyin: qīngdài guānmào; lit. 'Qing dynasty official hat'), also referred to as the “Mandarin hat” in English, is a generic term which refers to the types of guanmao (Chinese: 官帽; pinyin: guānmào; lit. 'official hat'), a headgear, worn by the officials of the Qing dynasty in China. The merchant is attired in a "changshan" or "changpao" or long robe. The robe worn in the photo was derived from the Qing dynasty-period "qizhuang" (the traditional dress of the Manchu people). Changshan were, and are, traditionally worn for formal pictures, weddings, and other formal Chinese events.

Credit-ticket System

Beyond the initial years, it became widely acknowledged that Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States voluntarily, free from any servile contracts or duress. Many emigrants either financed their own passage or received assistance from relatives and friends already residing in California. The prevailing method for the majority of Chinese immigrants during the 19th century was the credit-ticket system. Under this system, an emigrant would receive financial support for their passage in a Chinese port. Upon reaching their destination, the emigrant was expected to repay this debt using their future earnings. It is important to note that this system differed from the contract labor arrangement, where laborers were bound to serve for a specified duration.

The precise origins of the credit-ticket system remain uncertain. However, merchant brokers in Hong Kong were established to provide advanced passage funds, approximately forty dollars, to the emigrants. Corresponding entities in the United States were responsible for collecting these debts and aiding the newly arrived immigrants in finding employment.

Two merchants with pipes. No date, photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The stores and offices that the merchants of Chinatown had opened starting in the mid-19th century became the basis of real and symbolic power in the growing regional community of Chinese living in the American West. That power, including the ability to mobilize for social change within the narrow role afforded Chinese in the society, manifested itself in the family and district associations headed by local merchants.

“The merchant class has traditionally been the one sector of Chinese society able to foster unity and bring about social change,” wrote historian Thomas W. Chinn about the role of the merchant class in San Francisco Chinatown (and beyond). “The merchant-directors of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association must be well-established businessmen in the local community as well as outstanding members of their own family associations. They have already played a leading role in their own social circles before becoming merchant-directors, and they enjoy a great deal of respect. . . Thus the friendly corner grocer may simultaneously be the president of his family association and his district association as well as a merchant-director.”

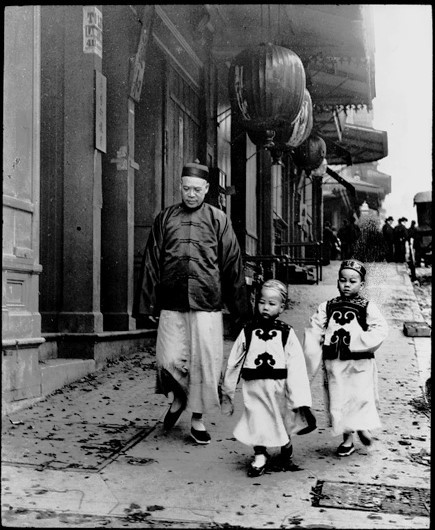

Lew Kan

“Children of High Class” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Merchant Lew Kan (a.k.a. Lee Kan) walking with his two sons, Lew Bing You (center) and Lew Bing Yuen (right). According to historian Jack Tchen, “Lew Kan was a labor manager of Chinese working in the Alaskan canneries. He also operated a store called Fook On Lung at 714 Sacramento Street between Kearney [sic] and Dupont. Mr. Lew was known for his great height, being over six feet tall, and his great wealth. The boys are wearing very formal clothing made of satin with a black velvet overlay. The double mushroom designs on the boys’ tunics are symbolic of the scepter of Buddha and long life.” The photograph appears to have found the trio walking down the south side of Sacramento Street below Dupont Street.

By the time photographer Arnold Genthe had photographed merchant Lew Kan and his two sons on Sacramento Street (as well as two other earlier photos of their four sisters in Portsmouth Square), Lew had already attained legendary status as one of Chinatown’s leading merchants. Born in 1851, Lew entered the US in 1866.

Author Roland Hui (in his biography of pioneer Chinese American industrialist Lew Hing), wrote about Lew Kan and his dry goods business called Lun Sing & Co. at 706 Sacramento Street as follows:

“He started Lun Sing, one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, around 1867, a year after he immigrated to the U.S. In 1896, the business gained notoriety by harboring a young Chinese revolutionary named Sun Yat-sen during his first visit to the continental United States. Sun advocated overthrowing the Qing monarchy and establishing a Chinese republic. His ideas were too radical for the politically uninitiated Chinese community. Kang Youwei, the architect of the ill-fated “Hundred Day Reform” in China in 1898, favored establishing a constitutional monarchy around Emperor Guangxu. Forced into exile after the power-hungry Empress Dowager crushed his reform, Kang launched the Chinese Empire Reform Association, also known as Baohuanghui (Save the Emperor Society), the following year in Victoria, Canada. Baohuanghui quickly gained widespread support among overseas Chinese since the idea of having an emperor at the top of the social order who ruled with the Mandate of Heaven had been ingrained in the Chinese psyche for thousands of years. The San Francisco Baohuanghui chapter was founded in 1899 at 146 Waverly Place. Lew Kan supported Kang’s political agenda despite having met Sun several years earlier, and in 1901 became the president of the San Francisco chapter of Baohuanghui. Many scholars observed that Baohuanghui was the first organization that evoked the patriotic sentiments of overseas Chinese. And when Liang Qichao, Kang's most famous student, stopped over in San Francisco during his 1903 America tour, thousands of Chinese flocked to listen to his speeches. As the man who organized these community-wide activities, Lew Kan's stature and influence in San Francisco Chinatown must have been substantial. In addition, he was one of the wealthiest Chinese merchants, reportedly owning several general merchandise stores with an estimated net worth of $2 million. That was an astronomical sum in those days. In addition, he was a director of the Kong Chow Company, a district association representing Xinhui."

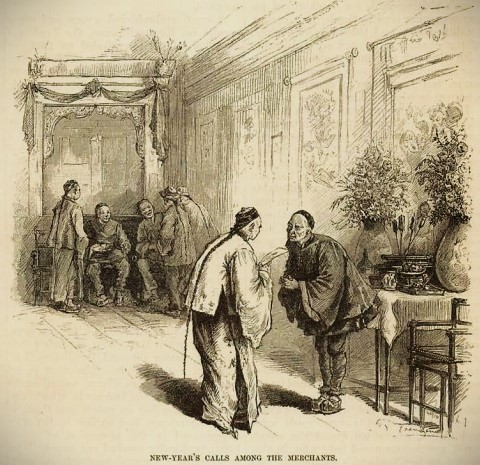

New-Year's Calls Among the Merchants" illustration from the article "The Sixth Year of Qwong See," published in Harper's Magazine, December 1880. The image may have captured merchants greeting each other at the Chinese Merchants Exchange on Sacramento Street perhaps on or about the fourth day of the Chinese New Year holiday period when business traditionally returns to normal.

Decline of Merchant Influence

The organizational expression of Chinatown’s merchant elite, the Chinese Six Companies, wielded considerable authority within San Francisco and beyond. The Six Companies and its constituent district associations comprised the quasi-government of Chinese America, offering social services, mediating disputes, and representing the community's interests to external forces. With the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882, their grip on power began to weaken.

Portrait of a merchant with fan and scroll. No date, photograph possibly by Shew’s studio (based on the detail of the end-table), from the collection of the Stanford Libraries.

The decline of the Six Companies’ influence can be attributed to various reasons. One significant factor was their inability to adapt swiftly to the evolving socio-economic landscape within Chinatown. As the community faced new challenges, including the punitive extension of Chinese exclusion with the Geary Act of 1892, the Six Companies struggled to effectively navigate these changes, leading to a loss of faith among the populace in their ability to address emerging issues.

The Geary Act of 1892 extended and strengthened the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, requiring most Chinese Americans – native and foreign-born -- to carry an internal passport in the form of certificates of identity or face arrest and deportation. It intensified discriminatory measures against the Chinese community, fostering widespread discontent and resistance.

In response, the Six Companies initiated a national boycott against the Geary Act. The boycott aimed to unify Chinese immigrants and their supporters across the United States, urging them to refuse compliance with the law as a form of protest. It gained substantial momentum, with significant participation from Chinese communities in various cities, voicing opposition to the Act's discriminatory provisions.

The board of directors of the Chinese Six Companies, no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Based on the screen panels in the background (which remain in the Six Companies’ meeting hall at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco), the photo appears to have been taken after 1906.

Despite its initial vigor, several factors led to the ultimate collapse of the national boycott against the Geary Act. First, the federal government intensified its efforts to enforce the Geary Act. Authorities conducted widespread raids and inspections, threatening deportation and imposing harsh penalties on those failing to comply. The fear of reprisals and the potential disruption to livelihoods coerced many Chinese immigrants into reluctantly acquiescing to the Act's demands.

Second, the broader American society exhibited little sympathy or support for the Chinese community’s plight. The prevailing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country and the lack of significant political backing from other institutions diminished the effectiveness of the boycott. Without widespread solidarity, the Chinese American community struggled to sustain its resistance.

Finally, the decision by the US Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893), dealt a major legal setback to Geary Act resistance and undermined the credibility of the Six Companies. The decision validated the Geary Act and created an environment of fear within the Chinese American community. The inability to overturn the Geary Act by legal means diminished trust in the Six Companies’ capacity to protect the community's interests.

Photograph of a merchant from Chinese Business Partnership Case File for Quong Lee Company, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from the files of the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office). The immigration investigative case file indicates that the individual in this photo was certified as a business partner and a "merchant" who was “able to travel to and from the U.S. as a ‘Chinese subject of exempt class’ under the ‘Chinese Exclusion Acts’ (1882-1943).” The Quong Lee & Co. (a.k.a. Quong Lee, Quong Lee Sing) operated what business directories from 1875 to 1905 variously described as a “tailor,” “general merchandise,” “clothing,” and “dry goods” business continuously at 828 Dupont Street. By the time this merchant sat for his photo in 1896, the national boycott led by Chinese merchant organizations against the Geary Act of 1892 had collapsed, and studio portraits such as this became an essential pieces of evidence to support applications for the coveted merchant exemption from the extended Exclusion Act.

This heightened sense of vulnerability played into the hands of tongs, which, capitalized on the weakened merchant community. Amidst the faltering influence of the Six Companies, tongs emerged as influential entities that would come to dominate Chinatown’s socio-political structure and shape mainstream society’s perceptions of the Chinese community for the next three decades.

“High-binders Retreat” no date. Photograph by Goldsmith Brothers (from the Cooper Chow Collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). Tong members at ease in front of their fraternal order's headquarters.

Tongs, in contrast to the Six Companies' diplomatic approach, adopted a more assertive stance in responding to discrimination and persecution faced by the Chinese community. Their readiness to protect their members (which also included merchants), and defy external pressures resonated with many disillusioned residents.

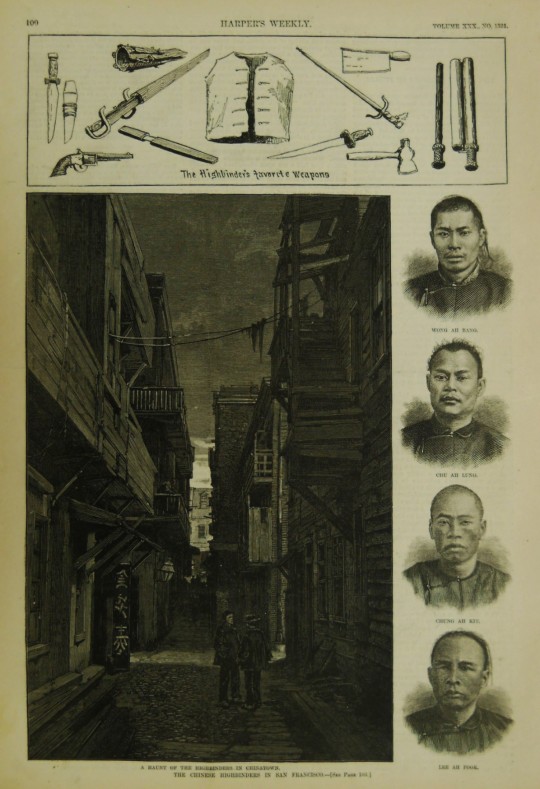

“A Haunt of the Highbinders in Chinatown.” Harpers Weekly, February 13, 1886 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

Moreover, the tongs during this period had begun to diversify their activities beyond traditional, illicitl sources of income such as prostitution, gambling, and drug distribution. Tongs began engaging in both legitimate businesses, including labor contracting for the Alaskan canneries. This diversification allowed them to accumulate resources, expanding their sphere of influence within Chinatown and beyond as alternative community governance structures, while still reserving often violent means to protect their interests.

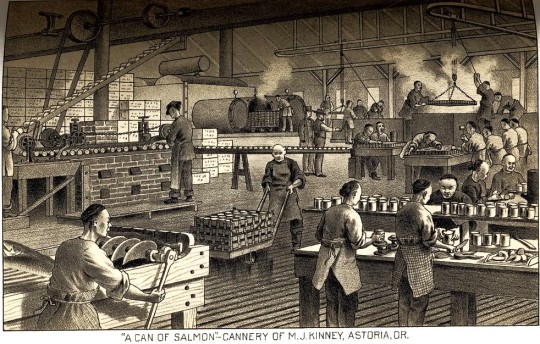

Chinese salmon cannery works in Astoria, Oregon, c. mid-1880s. Drawing from West Shore, June 1887, from the Special Collections, University of Washington). The early 20th century would be marked by violent struggles between tongs such as the Suey Sing and Bing Kung for control over the labor contracting business for the canneries.

The ascendancy of tongs at the turn of the century coincided with the republican movement in China. Historian Phil Choy wrote that the Chee Kung Tong, the original triad society, had been evolving in response to revolutionary movements in mainland China:

“Chee Kung Tong returned to its lofty political ideologies in 1900 when both Kang Yu-wei’s Reform Party and Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Party sought its assistance. Originally the Chee Kung Tong supported Kang Yu-wei, but as Dr. Sun’s ideology gained popularity, the Chee Kung Tong, switched allegiance. When in 1904 immigration officials did not allow entry to Sun, the leader of the Chee Kung Tong, Wong Sam Ark, and the Tong’s attorney Oliver Stidger, along with Reverend Ng Poon Chew and Reverend Soo Hoo Nam Art, worked successfully for his release. Sun stayed at the Chee Kung Tong headquarters and used the society’s newspaper, the Chinese Free Press, to propagandize his revolutionary cause. Accompanied by Wong Sam Ark, Dr. Sun went on a nationwide tour to generate support and contributions.”

The tongs’ economic power and their active involvement in fundraising for the republican movement not only showcased their financial strength but also demonstrated their ability to wield influence as an overlapping and sometimes counter-force with the merchant elite. This dual role as (1) economic powerhouse within the local community, and (2) significant contributor to a revolutionary cause overseas underscored their influence. The growth of that influence came at the expense of the merchant elite in shaping both local and international affairs.

Merchants, however, would continue to exert influence through clan organizations, tongs, business associations, Nationalist Party of China chapters, and Chinese “consolidated benevolent associations” in San Francisco Chinatown and communities across North America through the exclusion era, war, and peace.

The meeting hall of the Chinese Six Companies, c. 1920 (by then incorporated as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco. Photographer unknown (from the Jese B. Cook collection of the Bancroft Library).

Chinatown's merchant community would face new challenges to their capacity as civic leaders when the political center of gravity across US Chinatowns would shift again in the last quarter of the 20th century.

[updated 2023-12-28]

#Chinatown merchants#Sing Man#Choy Chew#Chinese Merchants Exchange#Fung Tang#Lai Chun-chuen#Chy Lung & Co.#Yee Ah-Tye#Chinese Six Companies#Kai Suck#Ann Ting Gock#Lew Kan#Chee Kung Tong#Quong Lee & Co.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

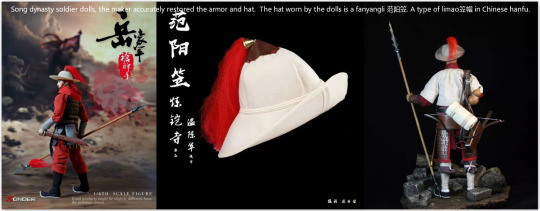

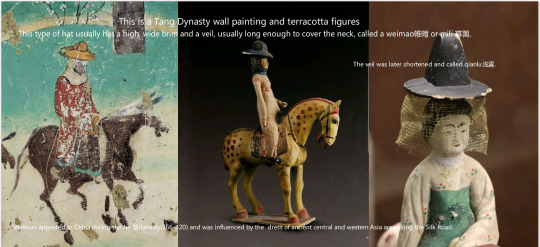

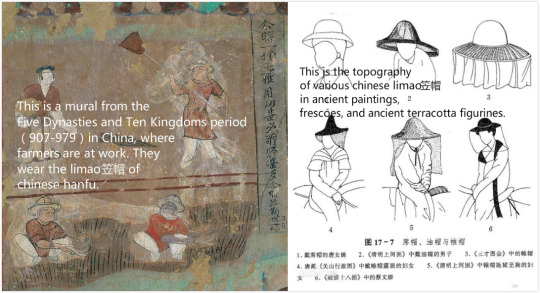

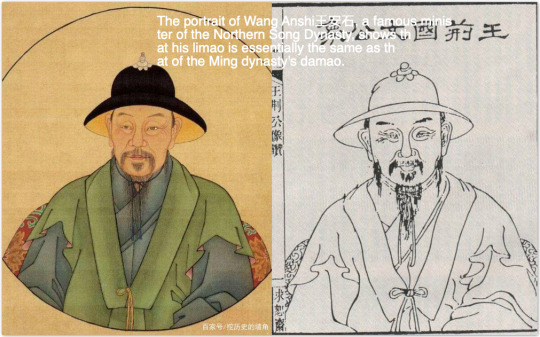

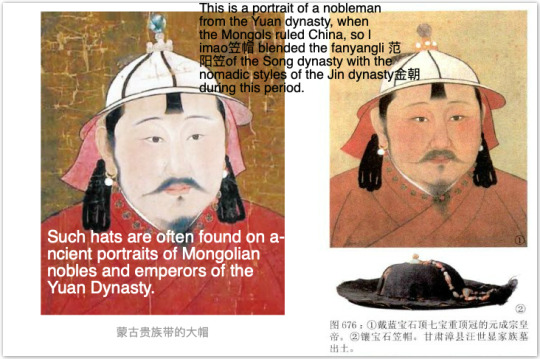

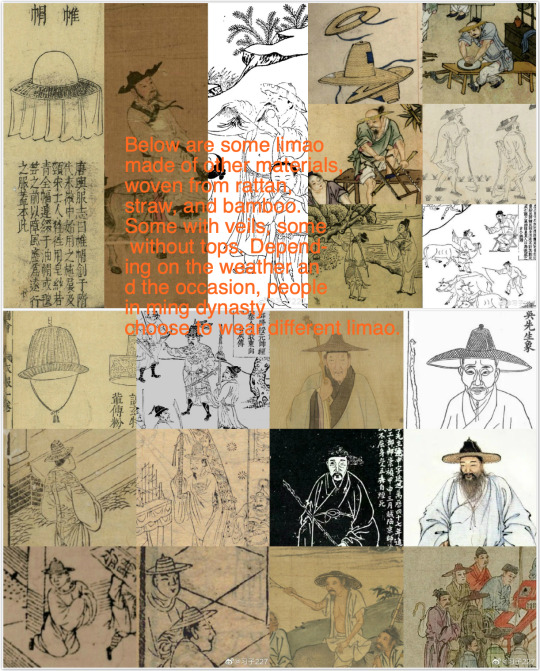

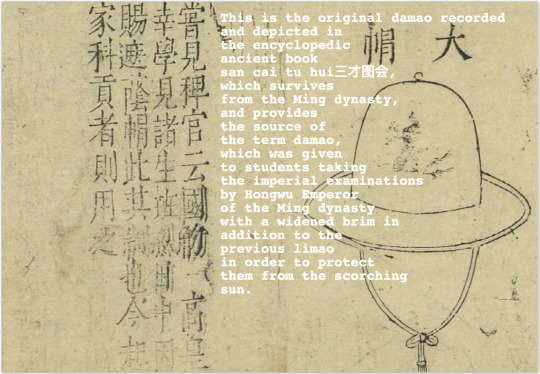

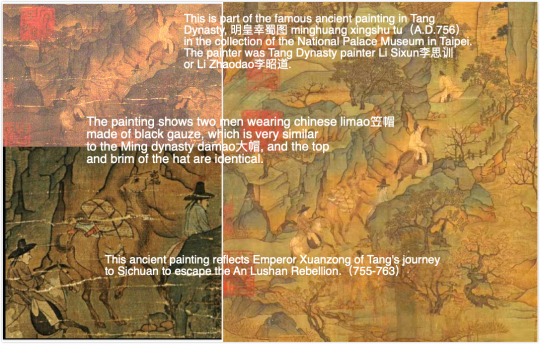

笠帽limao, a general term for a type of Chinese hanfu hat, characterized by a wide brim. The primary form had already appeared during the Shang and Zhou dynasties( 1600 B.C.-256B.C.), and its invention was naturally related to shading from the sun and rain, with a large brim that could both block the rain and shade the sun. In ancient China, limao笠帽 were made of many materials, including bamboo baskets, pouches, ramie, yarn etc. The shape of limao笠帽 is with usually large brim, round, square or pointed tops. The later it was developed, the more it resembled today's hats. In the Ming Dynasty this hat was called a damao大帽, yet it's been around before Ming, inherited from the Song Dynasty and earlier dynasties.

The picture below shows two limao unearthed from the tomb of the Yuan Dynasty minister Wang Shixian汪世显.

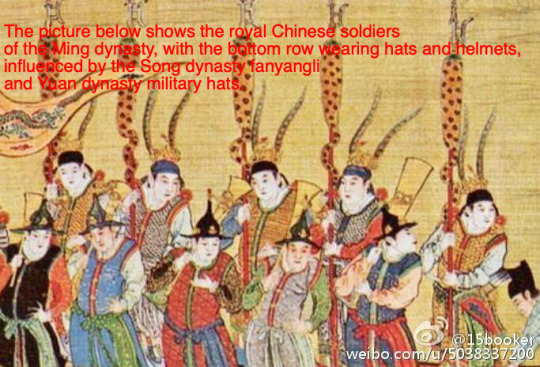

Then let's take a look at what the limao笠帽 looked like worn by Ming Dynasty soldiers.

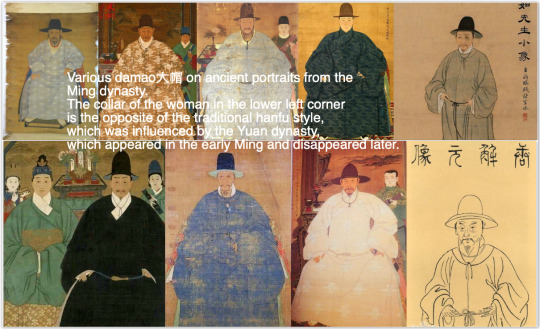

What about the damao大帽 worn by non-military officials and civilians in Ming dynasty?

So how did the term of damao in Ming dynasty come about? The origin of damao is recorded in an ancient book of the Ming Dynasty, san cai tu hui《三才图会》(1607). This book is an encyclopedic book written by 王圻Wang Qi and his song 王思义Wang Siyi, who were literature scholars and book collectors during the Ming Dynasty. Here is the quote 《三才图会》:“大帽,尝见稗官云:国初高皇幸学,见诸生班烈日中,因赐遮荫帽,此其制也,今起家科贡者用之。” Generally when Zhu Yuanzhang, the first emperor of the Ming Dynasty, saw the students taking the imperial examinations sweating in the scorching sun, he gave them damao to protect them from the sun.

The image below is a painting from the Tang dynasty, showing that the basic shape of the damao differs little from that of the Tang dynasty.

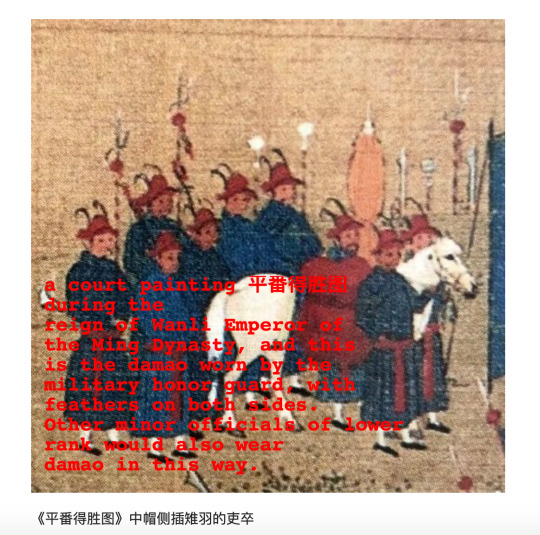

The 平番得胜图ping fan de sheng tu is currently housed in the National Museum of China and is considered to be an accurate portrayal of the Ming dynasty's army and is of high reference value.

The above is the consistent history of limao笠帽 in Chinese hanfu. limao was a very common hat in all Chinese dynasties, worn by all classes. The basic shape with a high top made of black gauze and a knotted cord appeared early on. Of course, hats with brims is a common thing for every culture and are found in all parts of the world, just as Eastern and Western civilizations coincidentally documented the prehistoric Flood.

For those interested in more specialized and complete information, here is a ten-minute video detailing the history of limao.

To summarize, limao was first seen in the Han Dynasty terracotta figurines, called li笠, and documented in writings in the ancient book 急就篇(48b.c.-33b.c.), but the brim was not as big as it is now, in the Northern Dynasty(386-581), limao was inspired by the Xianbei people whose ancestors were nomads in ancient Siberia, so the brim was widened, and the top of the hat was added (recorded in the Northern Dynasty mural) and is almost the same as now, after the consistent development recorded but not limited to the Tang Dynasty terracotta figurines and Song Dynasty paintings, especially that Fanyangli influenced the limao style of the Yuan dynasty, and then the Yuan emperor Kublai Khan added curtains behind the limao, and beads and feathers according to the Mongolian custom, and then Ming emperors removed the curtains in the early Ming dynasty, forming a variety of styles.

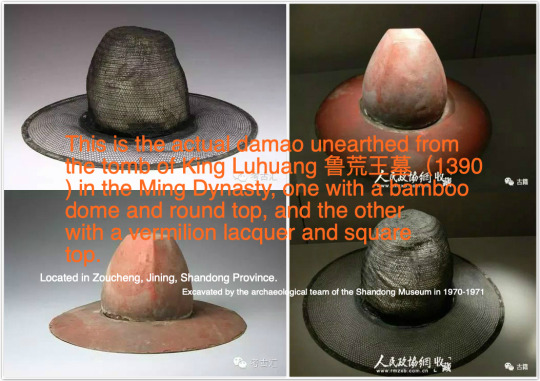

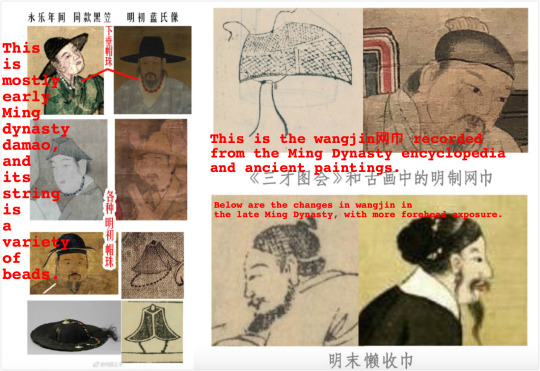

Facts about damao in Ming dynasty

1. damao was influenced by limao of all the previous dynasties, and arose spontaneously. ✔️

2. damao usually have round top, but there were also other forms of top, such as the quadrilateral.✔️

2. In the early Ming dynasty, influenced by the Mongolian style of the Yuan dynasty (Mongolia added the beads according to its own nomadic style), damao used the gems or beads as a string. ✔️

3. In the middle of the fifteenth century, Emperor Yingzong abolished the bead-string, stipulating that the damao could only be worn with plain string. ✔️

4. The adornment of damao was mainly on the top, with jewels, feathers, and red tassels.✔️

5. From ancient paintings, the decorative method of inserting feathers on one or both sides of the hat, is found in the Ming Dynasty and previous dynasties.✔️

6. damao usually matches with wangjin网巾, a kind of mesh scarf tied back the bangs neatly. ✔️

Now high-priced hanfu stores are making the damao exactly according to the Ming Dynasty style, and are considered historically accurate. However, some middle or low priced hanfu store are lazy and don't make it accurately, so the details are confused with another country' traditional hats with brim, or even worse. A few days ago a famous chinese artist accidentally used the picture of damao of that lazy store as reference to draw her super popular characters and post it on twitter, it could be controversial and offensive to some people from another culture who are not familiar with hanfu and lead to misunderstanding. And then she experienced cyberbullying which is really bad. (btw she also provides the correct ancient Ming portrait as a reference though

I have cautiously observed, and must state that the damao she drew does not show a very clear feature that significantly different from the Ming dynasty damao of a traditional hat from another culture, and I think one reference picture of damao from taobao store does have a slight problem and is ambiguous. Incidentally, the non-damao hat that worn by the other character has also attracted criticism is no problem and actually called yishanguan翼善冠, one of the traditional types of hats for Chinese hanfu, which I will describe later.

Well, you get the idea.

In a more general sense, was the ancient Chinese costume culture, while retaining its original form, influenced by xiyu culture (a general reference to non-Chinese countries on the Silk Road, the ancient cultures of Western and Central Asia and the ancient states, xiyu西域 literally meaning western region) and nomadic cultures such as xianbei culture? Yes, especially in the Tang Dynasty. For example, yuanlingpao圆领袍/rongfu戎服. Did ancient China radiate its costume culture to its neighbors(not all of them), leaving behind similar or even convergent forms, while at the same time they developing their own local characteristics? Yes. If a culture had close contact with China in ancient times, but is geographically separated from China by a long distance or even by the sea, the later its identity will become stronger, and what used to look like Chinese clothing will become less obvious, such as the kimono.

Here are examples of the basically accurate damao in style of ming dynasty by hanfu store. It does not contain all the types.

#china#hanfu#history#reference#chinese fashion#fashion#limao#damao#this long post is not intended to upset anyone#after all clothes are clothes and as long as they are worn by humans#they have commonalities and have their own characteristics according to different local conditions#after all that's how people dressed in ancient times.#it is possible that many times we are simply locked in an information cocoon and therefore prone to misunderstandings#including myself#Also I find it hilarious to write about this hat in such a serious and substantiated way#it's just hat#I don't know if I made myself clear enough or not#lol#my wording may have been imprecise and I apologize in advance if anyone was offended by it#again it was not my intention

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annals of Taihe 16 (492)

[From WS007.]

[Taihe 16, 14 February 492 – 1 February 493]

16th Year, Spring, 1st Month, wuwu, New Moon [14 February], banqueted the crowd of subjects in the Taihua Hall. When the Emperor first made the kings and dukes rise up, the bell frames then did not play music.

On jiwei [15 February], ancestral sacrifices to Xianzu, August Emperor Xianwen at the Hall of Light, using him to pair with the High Deity. Thereupon ascended the Numinous Terrace [lingtai], so as to observe the clouds' colour. He descended to dwell at the Qingyang Left Side-room, and set out government affairs. On every New Moon, he relied on it as the regular practice.

On yinyou [17 February], first used Taizu to pair at the southern suburbs.

On renxu [18 February], decreed to settle the sequence of the Agents [xing], using Water to inherit Metal.

On jiazi [20 February], decreed to cease with libations for the Founders [or “grandfather”][?].

On yichou [21 February], regulated that the various distant family members who were not sons and grandsons of Taizu, and [those with] a different family name who had been made Kings, all be demoted to become Dukes, the Dukes to become Marquises, the Marquises to become Earls. Counts and Barons were to continue as in the past. All demoted in their titles as Generals.

On wuchen [24 February], the Emperor presided at the Siyi Hall. Recorded the questions to the Flowering and Filial.

On bingzi [3 March], first used the first month of the season to worship at the temple.

2nd Month, wuzi [15 March], the Emperor moved to hold sway at the Yongle [“Forever Happiness”] Palace.

On gengyin [17 March], demolished the Taihua Hall. Arranged and begun on the Taiji [“Grand Eminence”] Hall.

On xinmao [18 March], ceased with cold food banquets.

On renchen [19 March], favoured the Northern Section Bureau, and successively observed the various departments. Toured and scrutinized the Capital District, and listened to and managed grievances and disputes.

On jiawu [21 March], began the morning sun at the eastern suburbs, and thereupon used it as the regular practice.

On dingyou [24 March], decreed sacrifices to Yao of Tang at Pingyang, to Shun of Yu at Guangning, to Yu of Xia and Anyi, and to Wen of Zhou at Luoyang.

On dingwei [3 April], decreed that the posthumous title of Xuanni be the Civil and Sagely [wensheng] Father Ni [nifu]. Announced the posthumous title at Kong's Temple.

[Master Kong, courtesy name Zhongni, had received the posthumous title Xuanni during Western Han.]

3rd Month, dingmao [23 March], toured and scrutinized the Imperial District.

On guiyou [29 April], scrutinized the western suburbs sundry affairs of suburban sacrifices to Heaven.

On yihai [1 May], the Chariot Drove to begin welcome the vapours at the southern suburbs, from then on considered it to be the regular practice.

On xinsi [7 May], used the King of Gaoli, Lian's grandson Yun as the king of his state.

Xiao Ze dispatched envoys to court with tribute.

This Month [13 April – 12 May], the states of Gaoli and Dengzhi both dispatched envoys to court with tribute.

4th Month, dinghai, New Moon [13 May], distributed the new statutes and orders. A great amnesty Under Heaven.

On guisi [19 May], the state of Qinie dispatched envoys to court with tribute.

On jiayin [9 June], favoured the August Lineage School, and personally asked the Broad Scholars on the righteousness of the classics.

5th Month, guiwei [8 July], decreed the Crowd of Subjects at Huangxin Fore-Hall to further settle the arrangements of the statutes, the drifting followers to be limited and regulated. The Emperor personally presided over and determined them.

6th Month, jichou [14 July], the state of Gaoli dispatched envoys to court with tribute.

On jiachen [29 July], a decree said:

To concern oneself with agriculture and put weight on grains is what is first in kingly government. To exhort and take the lead in fields and farmland is a lordly person's regular service. Now the Four Vapours are in felicitous sequence, the season is enriched with torrential and freshness. [We] ought to make use of heaven and divide the earth, and thoroughly put [our] strength into the eastern cultivated lands. However among the people of the Imperial City, those who drift around for food are multitude, they do not put into practice the supervisions and exhortations, sometimes the weed hoe neglects the season. Can dispatched clarifying envoys to examine and investigate [so that who] is industrious or indolent is hence known.

Autumn, 7th Month, gengshen [14 August], the Heir of Tuyuhun, Helutou, came to court.

On renxu [16 August], a decree said:

A King establishes officials and allots responsibilities, [his robes] fall down and he folds [his hands] with his duties completed, he wields the web and lifts the mainstays, the multitude eyes [of the net] are thus managed. Our virtue is beholden to knowing people, how will [We] be able to be reflective and perceptive when the followers turn aside from the righteousness of the lord's appointments and conferrals. From now on, when selecting and recommending, always use the final month [of the season] for the original bureau together the personnel section to weigh and choose.

On jiaxu [28 August], decreed the Combined Outer Staff Cavalier in Regular Attendance Song Bian and the Combined Outer Staff Cavalier Attendant Gentleman Fang Liang as envoys to Xiao Ze.

8th Month, gengyin [13 September], the Chariot Drove to begin the evening moon at the western suburb, and thereupon used it as the regular practice.

On xinmao [14 September], the state of Gaoli dispatched envoys to court with tribute.

On ziwei [18 September], decreed the King of Yangping, Yi, and the Supervisor of the Left, Lu Rui, to supervise 12 generals and 70 000 cavalry, and chastise the Ruanruan.

On bingwu [29 September], the King of Dangchang, Liang Micheng came to court.

The Minister over the Masses, Yu Yuan, yielded his position due to his venerable age.

On jiyou [2 October], used Yu Yuan as Thrice Venerable, You Minggen as Five-times Experienced. Also nurtured the venerable of the state, and the venerable of the myriads. The generals acted out the rite of Great Shooting. It rained, and they did not manage to complete it.

On guichou [6 October], a decree said:

The Ways of the Civil and Martial matters since ancient times have acted together, in the grants of awesome beneficence they surely rely on each other. For that reason the Thrice and the Five-times are the utmost in benevolence, but there still are the affairs of conquests and offensives. Xia and Yin were enlightened and percipient while still not setting aside the acts of troops and armour. As such, if Under Heaven there is only peace, to neglect warfare is perilous. And to not teach the people war can be said to be throwing them away.

Hence Zhou established the office of Marshal, and Han set up the duties of General, both by these means assisted the civil and strengthened the martial, their awesomeness and majesty [dominating] the Four Regions. The house of state, even though venerating the civil so as to holding dear the Nine Harnessed [regions], cultivated the martial so as to soothe the Eight Wildernesses. However in their methods for practising the martial, they were still not thorough.

Now then for instruction in the civil there are standards, [but] the teachings in the martial are faulty. Before generals on horses are shooting, first act to explain the models of the martial. [We] can direct to have the ministers prepare and repair the open spaces and enclosures. Should for the ceremonies with rows and columns, and the numbering of the five military implements, separately wait for later directives.

9th Month, jiayin, New Moon [7 October], greatly put in order the even and odd numbered ancestors. Sacrificed to the the Grand August Empress Dowager Wenming at the Dark Room.

On xinwei [24 October], the Emperor, since it was the Grand August Empress Dowager Wenming' second dreaded day [anniversary of her death], wept at the left side of the mound and renounced meals for two days, weeping without interruption in the sound.

On xinsi [3 November], the King of Wuxing, Yang Jishi came to court.

Winter, 10th Month, yiyou [7 November], the state of Dengzhi dispatched envoys to court to present.

On jihai [21 November], used the Grand Tutor, the King of Anding, Xiu, as Great Marshal; the Specially Advanced Feng Dan as Minister over the Masses.

On jiachen [26 November], decreed to use the merited subjects to pair at banquets at the Grand Temple.

On bingwu [28 November], the state of Gaoli dispatched envoys to court to present.

On gengxu [2 December], the Taiji Hall was completed. A great banquet for the crowd of subjects.

11th Month, yimao [7 December], relied on the ancient Six Rear-chambers, to evaluate and regulate the Three Rooms. Used the Anchang Hall as the Inner Rear-chamber, the Huangxin Fore-Hall as the Middle Rear-chamber, the four below as the Outer Rear-chambers.

12th Month [4 January – 1 February], bestowed on the elderly people of the imperial district dove-shaped canes.

This Month, Xiao Ze dispatched envoys to court with tribute.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

China is becoming more tolerant of some regional Han languages

China is becoming more tolerant of some regional Han languages

[ad_1]

LI SIYI tucks her hair behind her ears and takes a deep breath. The high-schooler and aspiring journalist sits in a mock television studio in a basement of China’s most prestigious broadcasting university, practising scripts of the sort that she will soon have to tackle as part of its entrance exam. When the time comes examiners will grade her poise and delivery. They will also assess the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

White Dwarf Seen Tearing Apart A Comet For The First Time

check it out @ https://tuthillscopes.com/white-dwarf-seen-tearing-apart-a-comet-for-the-first-time/

White Dwarf Seen Tearing Apart A Comet For The First Time

In a cosmic first, scientists have witnessed the moment that a white dwarf the remnant of a star that has shed its outer layers ripped apart a comet in its vicinity. The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The discovery was made using the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and NASAs Hubble Space Telescope. Observing the distant white dwarf 170 light-years from Earth, called WD 1425+540, they saw evidence that a massive comet had fallen towards the star and been tidally disrupted or torn apart.

Found in the constellation of Bootes, this white dwarf was first recorded in 1974. It is part of a binary system with another star, which orbits about 2,000 astronomical units (AU, 1 AU is the distance from Earth to the Sun) away.

As for the comet, well, it was rather huge, about 100,000 times as massive as the famous Halleys Comet in our own Solar System and with a much higher amount of water. It is also thought to be rich in the elements essential for life such as nitrogen, carbon, oxygen, and sulfur.

Nitrogen is a very important element for life as we know it, said lead author Siyi Xu of the European Southern Observatory, Germany, in a statement. This particular object is quite rich in nitrogen, more so than any object observed in our Solar System.

The finding is important because it lends evidence to the idea that other planetary systems have some of the same icy material as our own, which may have been transported via cometsto various worlds.

Up to half of all white dwarfs are thought to be polluted with infalling debris from asteroids into their atmospheres, although this is the first time comet-like material has been seen. It also hints at a region like our own Kupier Belt made up of ancient icy material around the white dwarf.

The discovery shows that icy material like this can survive the entire evolution of a star. This white dwarf would have once been a red giant, before it discarded its outer layers and left behind just the dense core of the old star.

How this comet moved from a distant orbit towards the white dwarf isnt clear, though. The researchers suggest it may have been pushed inwards by unseen planets in the system. Alternatively, this white dwarfs companion may have disturbed the distant belt of comets, or perhaps a combination of the two ideas took place.

But on the plus side, it proves were not alone in having icy material in our Solar System. And if comets delivered water and life here, where else did they do it?

Read more: http://www.iflscience.com/space/white-dwarf-seen-tearing-apart-a-comet-for-the-first-time/

0 notes

Photo

Shop in Chinatown, c. 1890. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (from the Granger Collection, Historical Picture Archive).

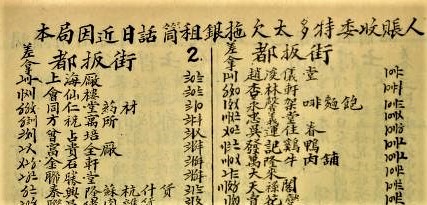

Right Before Our Eyes: Rediscovering Ti Hang Lung & Co. on Dupont Street -- 都板街

The flash photo of the interior of a store in old San Francisco Chinatown has remained a favorite subject of reproductions over the years (even by mass outlets such as Wal-Mart). Unfortunately, the information about personages and the nature of the business have been lost to living memory. However, the photo contains a conspicuous sign and, thus, an important clue for researchers of old Chinatown more than 130 year later.

The sign appears in the upper center of the frame and reads 泰興 (pronounced as “Tie Hing” in Cantonese). The Langley directory of 1895 lists a business by the name “Ti Hang Lung & Co. 818 Dupont.“ The 1905 telephone directory also provides verification in the form of an English-language listing as “Ti Hang Lung & Co. Mds 818 Dupont.” This poses the question of whether the entry in English corresponds to the Chinese signage seen in the photo, particularly given the inconsistent English phonetic renderings of that day. Fortunately, the Chinese section of the 1905 contains a handwritten Chinese entry for the address of 818 Dupont. The name 泰興隆 (canto: “Tai Hing Loong”) appears in the first column at the bottom of this page excerpt as follows:

Chinese Exchange section for Dupont Street (都板街) from the Pacific States Telephone and Telegraph Co. directory of 1905 (from the collection of the San Francisco Public Library). The Chinese entry also shows the type of business as 蘇杭 什貨 (lit. “Suzhou-Hangzhou, assorted goods”; canto: “So-Hong sup faw”).

The telephone directory listing also confirms the type of merchandise sold by Ti Hang Lung as indicated by the cloth banner above its business name in the photo. Researcher Qi Liu wrote in response to this posting as follows:

“Suzhou-Hangzhou stores were fabric stores. At one time there were hundreds of these stores in the Siyi regions. The name suggested they sold the finest silk from those 2 cities. In reality, these stores also sold silk and cotton fabrics made in Guangdong. The items on the racks do appear to be rolls of fabrics. Even though the character on the right is not clear, one can conclude from the other 3 that the characters, from right to left, are from classic line 億則屡中.”

The Ti Hang Lung company survived the 1906 earthquake and fire, and it would reestablish itself as the “Ti Hang Lung, Importer & Exporter at 846 Grant Avenue in the rebuilt neighborhood (with its pre-1906 Chinese listing of 泰興隆 油糖 什貨).

This exercise in simple detective work raises the larger question of why public and private academic institutions, libraries, auctioneers, and publishers omit information that illuminates the images in their archives or for sale. For example, the Chinatown 1905 Project provides anyone interested in the people and places in old Chinatown with a map regarding their whereabouts.

As a wise man once told me, “your history is your own.” His unspoken corollary was that no one else would give a damn otherwise.

Asian American history may be American history, but it will take Asian Americans to re-appropriate at least the photographic legacy of their pioneer generations, probably with the help of A.I. engines because the task of compiling the information or setting the record straight remains voluminous and enormous.

#Ti Hang Lung & Co.#I.W. Taber#San Francisco Chinatown#Dupont St.#Chinatown 1905 project#1905 Chinese telephone book

1 note

·

View note