#Shojo Kakumei Utena

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A little headcanon Utena and Anthy where they’ve grown up into just another gay couple walking around the thriftshop district on a Sunday or smth

#help I can’t stop drawing them!!#character art#character design#rgu fanart#rgu#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#shoujo kakumei utena#utenanthy#utena#anthy himemiya#adolescence of utena#utena tenjou

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gendered pronouns in Japanese vs English

In Revolutionary Girl Utena, the main character Utena is a girl (it says so in the title), but very conspicuously uses the masculine first person pronoun 僕 (boku) and dresses in (a variation of) the boys school uniform. Utena's gender, and gender in general, is a core theme of the work. And yet, I haven’t seen a single translation or analysis post where anyone considers using anything other than she/her for Utena when speaking of her in English. This made me wonder: how does one’s choice of pronouns in Japanese correspond to what one’s preferred pronouns would be in English?

There are 3 main differences between gendered pronouns in Japanese vs English

Japanese pronouns are used to refer to yourself (first-person), while English pronouns are used to refer to others (third-person)

The Japanese pronoun you use will differ based on context

Japanese pronouns signify more than just gender

Let’s look at each of these differences in turn and how these differences might lead to a seeming incongruity between one’s Japanese pronoun choice and one’s English pronoun choice (such as the 僕 (boku) vs she/her discrepancy with Utena).

Part 1: First-person vs third-person

While Japanese does technically have gendered third person pronouns (彼、彼女) they are used infrequently¹ and have much less cultural importance placed on them than English third person pronouns. Therefore, I would argue that the cultural equivalent of the gender-signifying third-person pronoun in English is the Japanese first-person pronoun. Much like English “pronouns in bio”, Japanese first-person pronoun choice is considered an expression of identity.

Japanese pronouns are used exclusively to refer to yourself, and therefore a speaker can change the pronoun they’re using for themself on a whim, sometimes mid-conversation, without it being much of an incident. Meanwhile in English, Marquis Bey argues that “Pronouns are like tiny vessels of verification that others are picking up what you are putting down” (2021). By having others use them and externally verify the internal truth of one’s gender, English pronouns, I believe, are seen as more truthful, less frivolous, than Japanese pronouns. They are seen as signifying an objective truth of the referent’s gender; if not objective then at least socially agreed-upon, while Japanese pronouns only signify how the subject feels at this particular moment — purely subjective.

Part 2: Context dependent pronoun use

Japanese speakers often don’t use just one pronoun. As you can see in the below chart, a young man using 俺 (ore) among friends might use 私 (watashi) or 自分 (jibun) when speaking to a teacher. This complicates the idea that these pronouns are gendered, because their gendering depends heavily on context. A man using 私 (watashi) to a teacher is gender-conforming, a man using 私 (watashi) while drinking with friends is gender-non-conforming. Again, this reinforces the relative instability of Japanese pronoun choice, and distances it from gender.

Part 3: Signifying more than gender

English pronouns signify little besides the gender of the antecedent. Because of this, pronouns in English have come to be a shorthand for expressing one’s own gender experience - they reflect an internal gendered truth. However, Japanese pronoun choice doesn’t reflect an “internal truth” of gender. It can signify multiple aspects of your self - gender, sexuality, personality.

For example, 僕 (boku) is used by gay men to communicate that they are bottoms, contrasted with the use of 俺 (ore) by tops. 僕 (boku) may also be used by softer, academic men and boys (in casual contexts - note that many men use 僕 (boku) in more formal contexts) as a personality signifier - maybe to communicate something as simplistic as “I’m not the kind of guy who’s into sports.” 俺 (ore) could be used by a butch lesbian who still strongly identifies as a woman, in order to signify sexuality and an assertive personality. 私 (watashi) may be used by people of all genders to convey professionalism. The list goes on.

I believe this is what’s happening with Utena - she is signifying her rebellion against traditional feminine gender roles with her use of 僕 (boku), but as part of this rebellion, she necessarily must still be a girl. Rather than saying “girls don’t use boku, so I’m not a girl”, her pronoun choice is saying “your conception of femininity is bullshit, girls can use boku too”.

Through translation, gendered assumptions need to be made, sometimes about real people. Remember that he/they, she/her, they/them are purely English linguistic constructs, and don’t correspond directly to one’s gender, just as they don’t correspond directly to the Japanese pronouns one might use. Imagine a scenario where you are translating a news story about a Japanese genderqueer person. The most ethical way to determine what pronouns they would prefer would be to get in contact with them and ask them, right? But what if they don’t speak English? Are you going to have to teach them English, and the nuances of English pronoun choice, before you can translate the piece? That would be ridiculous! It’s simply not a viable option². So you must make a gendered assumption based on all the factors - their Japanese pronoun use (context dependent!), their clothing, the way they present their body, their speech patterns, etc.

If translation is about rewriting the text as if it were originally in the target language, you must also rewrite the gender of those people and characters in the translation. The question you must ask yourself is: How does their gender presentation, which has been tailored to a Japanese-language understanding of gender, correspond to an equivalent English-language understanding of gender? This is an incredibly fraught decision, but nonetheless a necessary one. It’s an unsatisfying dilemma, and one that poignantly exposes the fickle, unstable, culture-dependent nature of gender.

Notes and References

¹ Usually in Japanese, speakers use the person’s name directly to address someone in second or third person

² And has colonialist undertones as a solution if you ask me - “You need to pick English pronouns! You ought to understand your gender through our language!”

Bey, Marquis— 2021 Re: [No Subject]—On Nonbinary Gender

Rose divider taken from this post

#langblr#japanese#japanese language#language#language learning#linguistics#learning japanese#utena#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#rgu#sku#gender#transgender#nonbinary#trans#official blog post#translation#media analysis

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

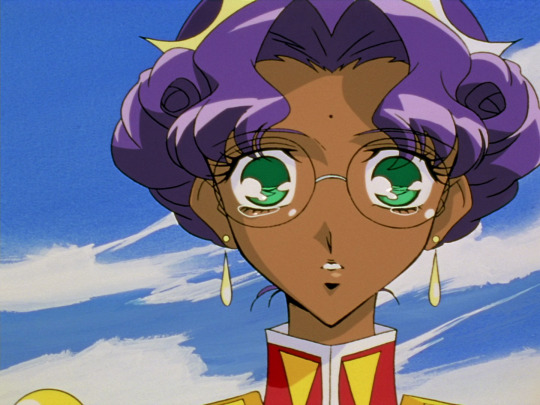

anthy's eyes

episode 2 / episode 5 / episode 12 / episode 25 / episode 30 / episode 33 / episode 34 / episode 35 / episode 36 / episode 38 / episode 39

#i was thinking rgu thoughts and these details popped up#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#shoujo kakumei utena#rgu#sku#anthy himemiya#akio ohtori#utena tenjou#parallels#gifs#gifs made by me :)#✮

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just another fly in the swarm

#nanami kiryuu#kiryuu nanami#revolutionary girl utena#shoujo kakumei utena#shojo kakumei utena#rgu#sku#la fillette révolutionnaire utena#la fillette revolutionnaire utena#nanami kiryu#kiryu nanami#drew

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

this idea did not leave my head for a month so i knew i had to draw it or else

#u#my art#revolutionary girl utena#magical girl#utena#shoujo kakumei utena#shojo kakumei utena#rgu#trans artist#mahou shoujo#utena fanart#fanart#1k#5k

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

She’s whatever you want her to be.

(Individual frames under the cut)

#anthy himemiya#revolutionary girl utena#rgu#shojo kakumei utena#utena#utena tenjou#saionji kyouichi#miki kaoru#juri arisugawa#nanami kiryuu#touga kiryuu#akio ohtori#prince dios

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#utena#revolutionary girl utena#rgu#shojo kakumei utena#i used to post this image on twitter every time i watched utena#but i dont think tumblrs album works like that so ill probably just reblog it every time#its such a good image

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

y'all think anthy and utena shit like this

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

anthy

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

In my heart of hearts, Nanami followed after Anthy post-canon

#pillowspace art#revolutionary girl utena#rgu#shoujo kakumei utena#sku#shojo kakumei utena#nanami kiryuu#kiryuu nanami#himemiya anthy#anthy himemiya#fanart#utena

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

And they were room mates…🗡️🌹

#learning to draw people just so i can draw a car and her gf kissing#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#utena tenjou#anthy himemiya#utenanthy#rgu fanart#rgu anthy#rgu utena#rgu

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Revolutionary Girl Utena is an Incredibly Meaningful and Emotionally Powerful Anime With Many Important Messages

The patriarchy is a toxic and deeply ingrained aspect of our culture that hurts everyone regardless of gender and social status, although ‘outsider’ women suffer from it the most - as they become the scapegoat and outlet for the suffering of others.

The concept of ideal masculinity is a myth that will basically kill anyone earnestly trying to reach it

The idealization and the demonization of women are both deeply sexist and harmful phenomena that spring from the same source

The romanticism of Fairy Tales shapes much of the way we as a culture think and is often used to reinforce regressive views of heroism and gender

Reality is a subjective fabrication. The way we view and process the world is so deeply shaped by our preconceived notions that we’re all basically living in different worlds.

Victims do not need to be morally perfect to deserve sympathy and support

Our conception of heroism is often interviewed with a condescending desire to deny victims, especially victimized women, their own agency.

Our memories are not as set in stone as we would like to believe and can easily be warped and manipulated based on our preconceptions or societal expectations

Clinging to the idea of childhood innocence past its moment will just corrupt into something much darker and uglier and probably incest-y

Gay

It’s a big mistake to think you’re the only one who can turn into a car

#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#utena#shoujo kakumei utena#rgu#sku#the adolescence of utena

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

red apple

episode 5 / episode 10 / episode 11 / episode 19 / episode 23 / episode 32

#the two apple slices in wakaba's bento were similar to apple slices in episode 5#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#shoujo kakumei utena#rgu#sku#miki kaoru#nanami kiryuu#utena tenjou#touga kiryuu#wakaba shinohara#souji mikage#mamiya chida#kanae ohtori#anthy himemiya#akio ohtori#✮

638 notes

·

View notes

Text

:(

#rei says stuff#utena#revolutionary girl utena#shoujo kakumei utena#shojo kakumei utena#wakaba shinohara#utena tenjou#tenjou utena#shinohara wakaba#rgu utena#rgu wakaba

778 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is my friend, Chu-Chu!

#chu chu appreciation post#chu chu#revolutionary girl utena#rgu#shojo kakumei utena#sku#utena tenjou#anthy himemiya#gif#series#90s anime#hes so cute i love him#my post

722 notes

·

View notes