#She’s doing a mrs. Doubtfire expression now. Help is on the way dear !

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

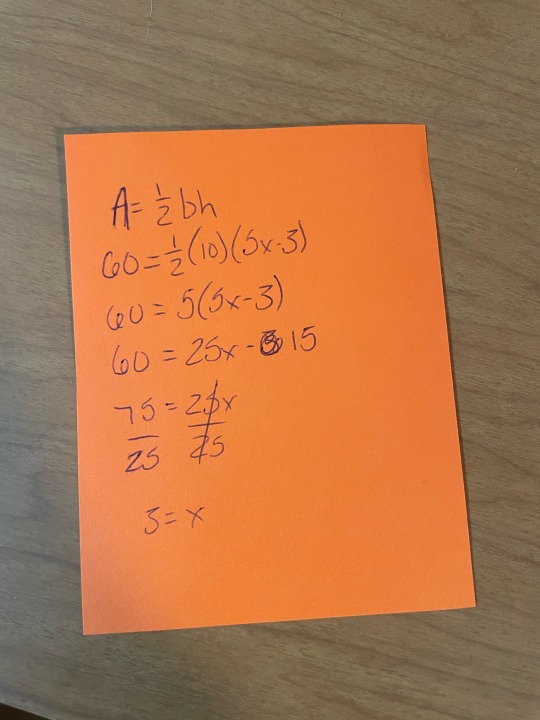

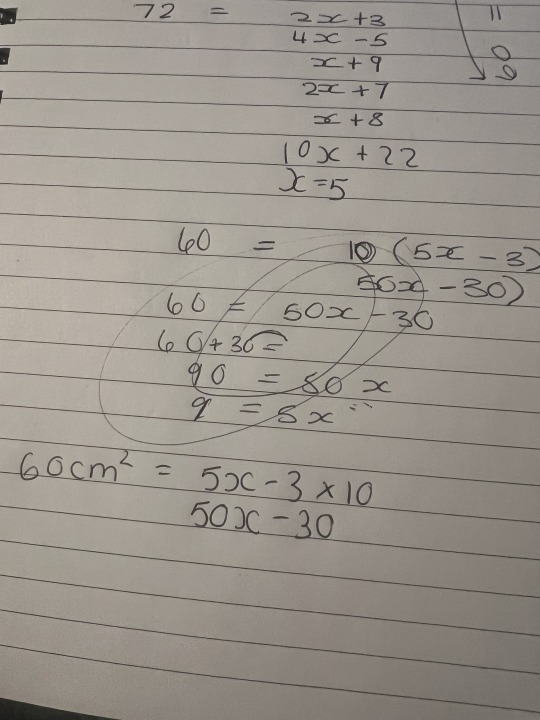

Ignoring my terrible handwriting, this should be how you solve it:

The math lover in me couldn’t resist lol

my sister says THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU and I say omg

She wants us to show our workings out and embarrass us 😭 shame

#She’s doing a mrs. Doubtfire expression now. Help is on the way dear !#jade’s asks#thank you so much from both of us

32 notes

·

View notes

Link

RuPaul's recent controversial comments heightened tensions between two communities that were once closely allied. What happened? Last week, in an interview with The Guardian that hyped the “radical message” of RuPaul’s Drag Race, the superstar drag queen was asked whether he would allow people whose gender identity was female to compete on the show. Regarding transgender women who have had breast implants or undergone hormone replacement therapy, RuPaul said they would “probably not” be eligible to compete on the show — “it changes the whole concept of what we’re doing” — and doubled down on Twitter by comparing trans drag queens to steroid-abusing professional athletes, before apologizing amid a wave of backlash. Whereas the drag and trans communities were once closely allied, this sort of antagonism has colored trans people’s perceptions of drag for years, especially among younger trans women and transfeminine people. The day before Drag Race All Stars’ season three premiere in January, a user of the subreddit r/Asktransgender asked “Who else has a problem with drag?” to describe the hurt she felt at being lumped in with the “man in a dress” by cisgender audiences. Responses were mixed: Some laid blame with individual performers, but many seemed to think the well itself was poisoned. One user called drag “frequently somewhere between casually and blatantly misogynistic,” while several went so far as to compare it outright to blackface. According to Ben Power, executive director of the Sexual Minorities Archive in Holyoke, Massachusetts, the last time in recent memory that drag itself was under such heavy fire was when it became a target of lesbian separatists in the 1970s. The only major difference today, he says, is that “the people doing the judging changed.” How did this happen? At what point did drag become the source of so much controversy under the queer umbrella? And most important: What do we do, now that there’s no going back?

While starting with crossdressing in Shakespearean-era theatre might seem a little too far back, it’s vital to note drag’s early, chimeric history before we get too far in the weeds. (This overview should not be considered comprehensive; as a white trans woman, I yield analysis of drag’s relationship with race to transfeminine people of color.) At one point, “female impersonation” was one of the most commonplace ideas in Western performing arts; young boys played female roles as a matter of course, and nobody would have thought to question their sexuality or gender. Drag as specifically queer performance did not yet exist, because the necessary context had yet to arrive.

By the 1800s, that context was well on its way in America. White men often portrayed female minstrel show characters, milking “man in a dress” humor alongside the shows’ racism. Yet even as the public devoured female impersonation in entertainment, cross-gender expression was otherwise thoroughly policed. In Columbus, Ohio, laws against public crossdressing were established in 1848, spreading to other cities in the following decades — partially an attempt to stop women from enlisting in the military but also meant to shore up God-given gender roles and discourage sodomy, too.

As “dressing up” in public became more dangerous, fledgling 19th century queer communities naturally sought to circumvent the new laws. Some of the earliest, albeit suspect, information we have about explicitly queer drag dates back to 1893; in Gay American History, Jonathan Katz reprints one doctor’s letter to a medical journal warning of “an annual convocation of negro men called the drag dance, which is an orgie of lascivious debauchery.”

Over ensuing decades, lines between drag, crossdressing, and transsexual identification blurred significantly, separated only by semi-porous membranes of politics and genderfuckery. As minstrel shows gave way to the rise of vaudeville and radio, drag drifted away from the mainstream to become a staple of gay nightlife, bringing with it a new paradigm for queer identification. In How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States, Joanne Meyerowitz notes that the 1950s “female impersonator” community served as a safe haven for prospective trans women to sort out their gender issues. Queens of the time did more than carefully impersonate celebrities and replicate “feminine” mannerisms: Many underwent early hormone replacement therapy to grow real breasts, and would provide “purple pills” to their less experienced charges along with “encouragement to pursue a woman’s life offstage.” One trans woman who worked as a female impersonator asserted in an interview that although most queens had once denied any desire for bottom surgery, she knew “half a dozen impersonators…[who were] saving for the operation” by the mid-1960s. Knowing others who had surgically transitioned, she believed, had mollified their fears. Perhaps nobody was more emblematic of drag’s nebulous placement within queer identification than Sylvia Rivera. Widely considered to be one of the instigators of the Stonewall riots in 1969, Rivera is today revered as something of a saint within the transgender community — somewhat ironic, as Rivera herself rejected that term and others. “I’m tired of being labeled. I don’t even like the label transgender,” Rivera wrote in a 2002 essay. “I just want to be who I am.” Rivera’s sense of gender seemed too expansive for any one word, and she drifted through countless categories over the course of her life. But one identity the STAR co-founder never disavowed was “queen.” These fluid dynamics of identification and belonging are evident in America’s first transgender periodicals. Drag magazine printed tips on hormone therapy, gender identity clinics and gender-affirming surgeons. Later issues gave pride of place to erotic centerfolds but still celebrated civil rights successes, like a disabled trans woman’s 1980 request for bottom surgery — “the first time a federally funded medical care program [Medicaid] has recognized transsexuality.” The reverse was true for magazines like Transgender Tapestry (originally TV/TS Tapestry), published from 1979 to 2008. Much of each issue focused on building “transvestite/transsexual” community, but drag featured prominently in its news coverage and analytical essays. Even drag queens who didn’t necessarily identify with transsexuals or crossdressers fought for the rights of both. A 1975 Drag special supplement opened with “The Drag Times,” a short news section dedicated to transgender civil rights struggles. One story told of drag queens and allies who picketed a hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district to protest housing discrimination and police mistreatment. That spirit would continue for decades; in an essay for Transgender Tapestry’s Summer 1997 issue, “What Do Drag Queens Want?,” Tim Denesha writes that “drags want...to make the world a better place,” noting the thousands raised for AIDS research yearly through the drag circuit’s grassroots Imperial Court system. A primary reason for much of this inter-community cooperation was the consolidation of political power. Drag queens, transvestites, and transsexuals of the 1970s shared an obvious set of common goals, which include abolishing the myriad of laws that outlawed crossdressing across America. Gender-conforming gay men were no help; a 1975 Drag essay noted that “the gays in their movement for liberation seemingly feel that drags have a worse public image, and so have virtually disowned us.” But those networks had more practical day-to-day purposes, such as keeping people alive. STAR, the organization founded by Rivera and fellow queen Marsha P. Johnson, served homeless queer youth of color, regardless of categorical identification. This would become invaluable during the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s; trans women were among those frequently cast out from their disease-fearing biological families, finding their way to drag families instead (as can be observed firsthand in Jennie Livingston’s iconic documentary Paris Is Burning). The early 1990s saw an explosion in the East Village drag scene, stoking flames for a comeback of female impersonation in cisgender-friendly contexts. But it was a San Diego–born queen who built them into a roaring bonfire: RuPaul. After releasing his hit single “Supermodel” in 1992, drag exploded, becoming a mass-media sensation for much of the decade. “RuPaul was the cover girl of the ’90s,” as sociology scholar Suzanna Danuta Walters notes in her book All the Rage: The Story of Gay Visibility in America. Elsewhere in pop culture, films like To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar (1995) and The Birdcage (1996) were opening-weekend hits, and Mrs. Doubtfire (1993) became a national touchstone. “[C]ross-dressing, straight-talking drag queens emerged as our Dear Abbys — providing sassy but affectionate insight into the vicissitudes of heterosexual romance,” writes Danuta. Yet though the “curious cultural fascination” with drag performers burned hot, it did “not necessarily entail a challenge to traditional definitions of gender. [....] In films and popular culture generally, drag becomes a safe and circuitous way” of dealing with queerness, rather than a radical cross-gender experience. A major part of this was clearly the emphasis on cisgender drag queens; in the 1990s, no trans queen could hope for RuPaul’s level of fame and acceptance. The drag boom dimmed by the mid-’90s, but it came with more than its fair share of cultural osmosis. For one thing, drag no longer had a “public image” problem — at least, not as far as gay men were concerned; a quick rewrite of drag history was all that was needed. Julian Fleishman’s 1997 book The Drag Queens of New York, compiled through interviews with RuPaul and his contemporaries, casually opines that “when a man who wishes to be a woman…succeeds in becoming one, he is no longer a drag queen” and that though real queens might “experiment” with transitioning, “they invariably stop short of the surgical point of no return.” But though the historical revisionism of gay men’s relationship with drag was damaging, another component of the ’90s drag boom had deeper effects: Cisgender Americans now had a whole new way of looking at and talking about transgender people, and many manipulated that vocabulary to twisted ends. Read more

0 notes