#Scotsgate

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Elizabethan Townhouse

I was recently sent an email asking what was on the site of the Elizabethan Town House at the north of Marygate. This goes around the houses a bit but it’s a fascinating story taking in so many unrelated subplots! The Elizabethan Town House, formerly the Avenue Hotel was built in 1899 by Joseph Weatherston (1836–1910). However, to answer the question of what was there before the Avenue, we have to delve further back in time.

The Elizabethan Town House

It is now hard to believe, but the Scotsgate was once the same size as the Cowport. A single-carriageway wooden bridge (later replaced by a stone causeway) spanned the 200 feet of the ditch in front of the walls. (This is why the road widens out to the north of the car park entrance: that is the point at which “land” was reached again.)

English Heritage impression of the bridge across the moat at Cow Port based on a drawing dated 1719. The bridge outside the Scotsgate would have been very similar.

Dr John Fuller, in his 1799 History of Berwick complains bitterly about the Scotsgate and its narrow bridge, and the dangers it posed. And with good reason: remember—pedestrians were vying for space with traffic in both directions, and those on foot were coming off worse. It was probably as a result of Fuller’s remonstrations that in 1806, the Council gained permission from the Board of Ordnance “for taking down and widening the Scots Gate and the Draw Bridge leading thereto, so as to render the northern entrance into the town more accessible”. In the end, probably due to cost, just the east pedestrian archway was added. Note, there was a gate inside: the town was being locked down every night until about 1815!

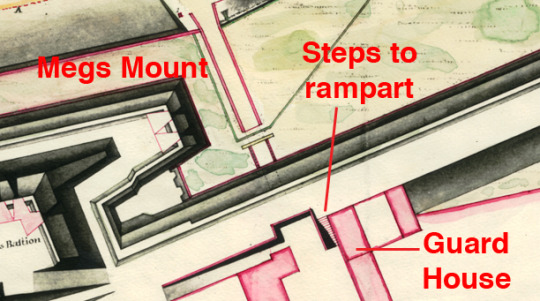

Detail from OS 1st edition map, 1852.

The gate hinges can still be seen in the East gateway.

If you look at the pedestrian archway on the east side and the archway over the Cockle Steps” leading to Greenside Avenue, we can gain some insight as to what happened. Originally, where the pedestrian archway is, there was a flight of stairs leading to the rampart. We also know that there was a guard house at this side of the Scotsgate. One can see the stonework of the Cockle Steps arch has been roughly dismantled and there has been no attempt to “finish” it in any neat way. This is lucky for the building detective, as it shows the arch must have projected over what is now pavement, under the rampart steps, forming a barrel vaulted roof to the guard house.

Detail of 1792 plan showing Scotsgate.

The rampart steps were taken down in order to create the new pedestrian archway. We can see in the Cockle Steps arch how only just enough has been removed to allow this. What happened to the guard house is unknown. It may have been downsized, rebuilt (unlikely) or abandoned. Whatever its fate, we know that 80 years later, Joseph Weatherston unblocked what was there to create Greenside Avenue.

Left: the east pedestrian gateway. Right: the Cockle Steps archway. Note how the stonework projects from the wall and has been removed just enough to build the new arch (circled).

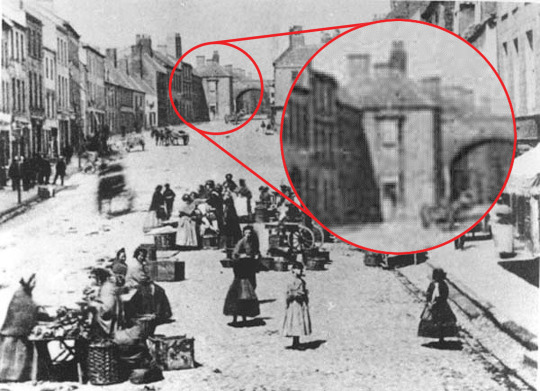

In 1857 the thorny question of the Scotsgate raised its head once more. The problem was now that since the arrival of the railway in 1844, the majority of people walking up and down Castlegate favoured the west side, closest to the station. A square building, known then simply as “Miss Gardiner’s house” had occupied the site since the late 17th century at least (see 1792 plan above). It projected awkwardly beyond the natural street frontage. This meant that anyone walking up the west pavement on Marygate had to either use the original vehicular road, or cross to use the east footpath, neither deemed desirable. Alderman Bogue believed the best solution was to demolish the projecting wing of the house and build a second vehicular carriageway and in its place. Later that month, however, it was resolved to leave the house alone, widen the existing vehicular arch and add a west pedestrian archway. In February 1858 the Berwick Journal took the Board of Health (who were in charge of the project) to task declaring the alterations to be a “Waste of Money!”, and that “[the public] do expect to see some benefit commensurate to the outlay [of public money]; this, however, we regret to say, they are rarely privileged to see, and in the case of the improvements at the Scotchgate they never will.” In May the Board decided on a plan of action; to widen the existing gate to the east by 6 feet to 18 feet 3 inches, raising the arch by 1 foot, and to add a west pedestrian footpath at an estimated cost of £40–£45. Work commenced demolishing the arch in September that year. The Berwick Journal, like many a modern day tabloid, without any sense of contrition, pronounced its U-turned opinion once more: “Now that it is down, and everybody can see what a great advantage its absence is, in every respect, we trust that they will by every means in their power endeavour to be released from the obligation of building it up again, in any form whatever.” The paper went on to suggest all that was needed was a ramp from the east side of the opening up to the ramparts. Thankfully, the Board of Ordnance stuck by its insistence that the rampart was rebuilt! But what of Miss Gardiner’s house? The Journal had a point when it demanded that the house should be purchased, “at any price and pulled down”, so that people could actually see the new west pedestrian archway ahead, instead of missing it and using the road. While they were at it, “the Corporation might buy that old, rickety, squinting thatched house […] which disfigures the East side of the entrance to the town.” (Situated near the B&M supermarket entrance by the Castlegate car park, it seems to have been used as a toll house.) The paper went on to suggest it being replaced by a new building “in the Edinburgh fashion”, the money being recouped by selling or letting the flats and offices therein.

Marygate, in the 1860s, after the Scotgate had been widened but before “Miss Gardiner’s House” (inset) had been demolished.

“Miss Gardiner’s house” had been occupied by a now elderly Guy Gardiner (1768–1855). He had been the Master at the first Grammar School between 1806 and 1848; only the third since 1691! The house had come as part pay with a salary of £80 a year. The original grammar school was nearby and now may form part of His two spinster daughters, Mary JS Gardiner (1804–?) a retired teacher, and her younger sister, Jane S Gardiner (1808–?) another teacher, were obviously looking after their father. The 1861 census shows that, following the death of their father, they were joined by a “cousin” the 14-year-old Jane JS Gardiner who had been born in Malta. Twenty years later, we find that young Jane was married to Thomas Fair Robertson Carr, an agricultural merchant. It is not clear whether the house sale was by mutual consent or by compulsory purchase, but by October 1881, it was to be offered to the Urban Sanitary Authority for £1625 and the projecting wing finally demolished.

Advert for Carr’s business in the Berwick Advertiser, 1878. Note the name of the premises—”Scotch Gates”.

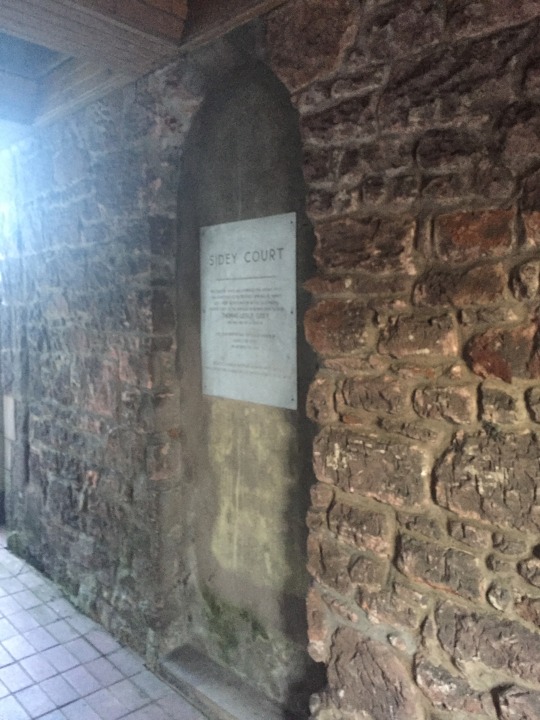

But what was happening across the road at the site of the Elizabethan Townhouse? Examination of the OS 1852 map shows a very similar building layout with an archway leading through to Sidey Court, then a stonemason’s yard. Inside the arch is a blocked doorway that no doubt led into a pub called the White Hart. (Prior to this it was called the Sir Francis Burdett after the very popular reformist MP (1777–1844) elected to Middlesex, and Westminster.)

Detail from OS 1st edition map, 1852. Note that Greenside Avenue does not yet exist.

A plaque on the blocked up door to the White Hart commemorates Councillor Thomas Sidey after whom the courtyard is named.

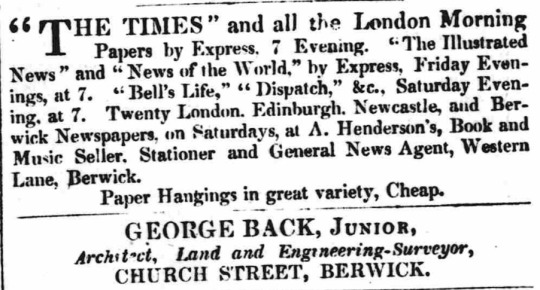

The date at the eaves states 1899 which is probably the date the Avenue was built as the first mention of it I can find is 1901 when the landlord was a Mr Elliott. Before Eliot or, indeed, Weatherston, the property belonged to George Back (1801–1879). Living in Church Street (1851 census) he and his sons George (c.1827–1874) and James (1835–?) were the stonemasons to whom the yard and buildings belonged. George Jnr must have had an excellent education as by 1855 he was advertising himself as an “Architect, Land and Engineering Surveyor”.

Advert for George Back in the Illustrated Berwick Journal, 1855.

In 1856 he fortuitously bought the lease of the Tweedmouth quarry. Fortuitous as in 1858, the King’s Quarry became the location of Tweedmouth Cemetery. Newspaper adverts from March 1857 now describe him as an “Architect and Sculptor” supplying gravestones at “The Studio, Scotchgate”, the salesroom of the family business.

Advert for George Back in the Illustrated Berwick Journal, 1857.

By the time the 1861 census was taken, it would appear that George Snr and James had left Berwick. What had happened? We will probably never know but in July 1860 George and James had applied for passports. A mere two months later, gone is any mention of his being an architect and sculptor; gone are the cemetery monuments. Instead, George is reduced to selling flagstones and other building materials. This would explain why his occupation in the 1861 census is listed merely as “merchant”. The change of business must have been due to the departure of George Snr and James; with nobody to make the gravestones, there were none to sell. It suggests that business had taken a downturn, possibly because, or as a result of George Snr and James’s departure to Ottawa, Canada. By now George would have been about 60: he died at James’s house there in 1878.

Back in Berwick, in 1871, George Back Jnr was facing bankruptcy. Three years earlier, he had attempted to diversify selling ironmongery but to no avail. After three years of pitiful adverts attempting to offload a quantity of roof ridge tiles, George died in 1874.

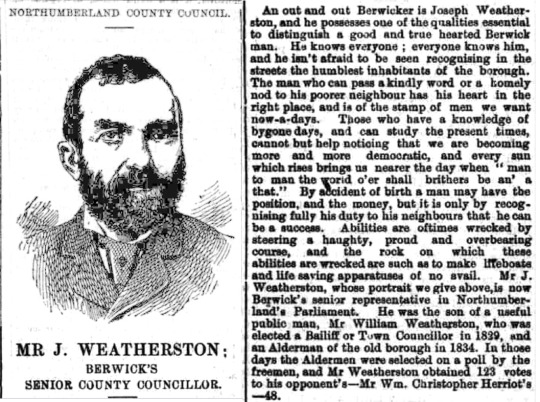

It may have been then that Joseph Wheatherston acquired the property. He was a slater and plasterer from a family who had been in that trade for some years, starting (at least) with his grandfather Thomas Weatherston. Thomas had two sons, Joseph and William, who entered the family business. William (1799–before 1861) appears to have been working with his father from Chapel Street (1837) and then Woolmarket (1855). William was also the landlord of The Globe on Chapel Street. His brother Joseph was working in West Street. Joseph became a Councillor is 1859 and died in 1870. That year, Joseph Weatherston—son of William—took over the running of his uncle’s operation. He now lived at 1 College Place. In 1876 he was elected to Berwick Council and by 1885 become an Alderman. He later represented Berwick on Northumberland County Council.

An article in the Berwickshire News and General Advertiser, 19th Feb 1889.

Weatherston continued as a slater/plasterer for some time. Among the buildings he worked on were the Masonic Hall in 1862 (built on the site of a storage yard he owned) and the Literary and Scientific Institute (Library and Museum, now Costa Coffee) in 1871. In 1885, he had the remains of the old guard house by Scotsgate demolished and created Greenside Avenue and later, the Avenue Hotel.

The date of the building of Greenside Avenue.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caravan with a View

May0219

#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#iphoneography#jumpneo shoots#black and white#lake district#braithwaite#scotsgate holiday park#awesome clouds

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Hole Lot of History

There was a recent query on Facebook/Forgotten Berwick about a large hole in the north face of the Elizabethan town walls. The hole in the wall is an unfinished gateway.

The unfinished postern gate between Cumberland and Brass bastions.

The Elizabethan walls were, unlike their medieval predecessors, meticulously planned—geometry was everything. They were designed, with, or despite the “help” from two Italian consultants who actually knew what they were doing. The detail from the “architect’s plans”, dating to 1561 by Rowland Johnson the master mason, that Cumberland Bastion is halfway between Megs Mount and Brass Bastion. The unfinished gateway is halfway between Cumberland and Brass despite being offset from the Wallace Green/Low Greens road to Edinburgh—that was doomed to be cut off. Similarly, if you look closely by the crease in the map, there is a similar feature halfway between Megs and Cumberland. They are intended to be small secondary gates (called posterns) that allowed troops to easily access the outside fields, here at the narrowest points of the ditch like at the Cow Port.

Detail from Rowland Johnson’s 1561 map.

The 1561 map even shows a bridge outside a planned postern at the midway point between Windmill and Kings Mount. There is no evidence of this or the one by Scotsgate having been built. Indeed, by 1570, the defences were incomplete. It is wrong to say they were finished in 1570; better that they just halted the project in 1570.

A scathing letter from Lord Hunsdon, the Governor at Berwick to Queen Elizabeth in 1568 reads:–

“Concerning Her Majesty’s new fortifications at Berwick, he must confess the main-wall is marvellous beautiful, but the town as it now remains is very weak and out of order. It is weaker than before by reason that the bell-tower and the fortifications, which were very strong, are pulled down, the old wall ha˛s fallen down five places, and palle [wooden palisade] set up instead of wall, and the rampire of the old wall taken away. The new work is in no order, either with rampire, gates, posterns or bridges. Thinks the Queen has small pennyworths for so much money, and cannot tell why the Castle and other places were pulled down…”

And yet a look at two 18th century maps suggest the idea may have been revived. In one, dated 1751, two dotted lines seem to indicate paths crossing the ditch at these points.

Detail from the 1751 plan showing the two “pathways” (highlighted).

The other map, from a similar date, shows a more clearly defined access to new external ravelin defences. (These were never realised; the Georgians made minor alterations along the riverside walls.)

Detail from the post-1745 plan showing a bridge to a ravelin (highlighted).

The bottom of the postern gate is elevated from the water-filled ditch which would have been crossed by a bridge, though probably narrower, to this English Heritage interpretation at Cow Gate (above) and the original 1719 plans upon which it is based (below). This is what the Scotsgate would have looked like originally!

That wasn't the end of the story, however. Some may remember when the vandals of the 1960s yet again revisited the idea of knocking a new gate through the walls near the Scotsgate to create a one-way system. Thankfully, that never happened, but one can't help thinking sometimes that there might be some merit in completing Sir Richard Lee’s work by finishing the original gate near Wallace Green to act as another route through the walls.

Detail from 1960s plan for a part of a one-way system in Berwick.

1 note

·

View note