#San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Awards Season 2024-25: Awards Round-Up 12/16 + Critics' Choice Award Nominations

Another week, another eight groups to process. I could wait until late on the 16th and add in the multiple groups announcing that day – but I’ll save them for the 23rd. This week’s contestants are: African-American Film Critics Association (AAFCA) Boston Online Film Critics Association (BOFCA) Chicago Film Critics Association (CFCA) Las Vegas Film Critics Society (LVFCS) Phoenix Critics…

#2024 Films#2024 in Film#African-American Film Critics Association#Awards Season 2024-25#Boston Online Film Critics Association#Chicago Film Critics Association#Critics&039; Choice Awards#Film Awards#Las Vegas Film Critics Society#Phoenix Critics Circle#San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle#St. Louis Film Critics Association#Toronto Film Critics Association

0 notes

Text

2024 San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle (SFBAFCC) Winners: 'Anora,' 'The Brutalist,' 'Sing Sing' Earn Top Awards

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

We were greatly saddened by this announcement from the San Francisco Silent Film Festival. R.I.P.

STEPHEN SALMONS 1958–2023

Stephen Salmons, cofounder of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and its artistic director through 2009, died on February 10. We join his friends and loved ones in mourning this great loss. A writer, performer, and filmmaker born in Santa Cruz in 1958, he made his home in San Francisco, where he became half the team that turned SFSFF from a dream into a reality. His knowledge ranged widely and deeply across literature, music, film, theater, and he drew from it all to the benefit of our festival audiences. In 2006, he received the Marlon Riggs Award from the San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle in recognition of his unique contribution to the city’s cultural landscape. Steve, of course, was much more than titles, accomplishments, or a list of works can convey. He was modest about his own artistic endeavors but was the first to encourage and applaud the artistic pursuits of others. He especially relished when he could inject a bit of ballyhoo into a festival program and the kinships that quickly form over a fresh insight or discovery made chatting between shows. Above all he valued kindness and that came through in his dealings every day. We will remember him most as a warm and witty colleague and friend who took visible delight in the playful exchange of ideas. He will be sorely missed. We send our most heartfelt condolences to his wife Melissa Chittick, with whom he cofounded SFSFF and shared a life for 24 years. Our thoughts are with her at this difficult time.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acclaimed Ukrainian documentary ‘20 Days in Mariupol’ secures top honor as Best Documentary Feature at San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle Awards 2023

The San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle (SFBAFCC), previously known as the San Francisco Film Critics Circle, has unveiled the winners of its 2023 film awards. The Ukrainian film ‘20 Days in Ma Source : www.weareukraine.info/acclaimed…

0 notes

Photo

1st ✧ Benedict and Claire Foy talk TELOLW with On Demand Entertainment.

2nd ✧ Benedict training and rehearsing with his stunt coordinator for TELOLW: x x x

4th ✧ New project announcement: Benedict will star in Netflix adaptation of Roald Dahl´s The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar And Six More, alongside Ralph Finnes and Ben Kingsley.

Wes Anderson set to direct. (Jan 6)

Dev Patel joins the cast. (Jan 7)

5th ✧ Benedict and Claire Foy talk TELOLW with Elle.

✧ Benedict wins Critics Best Actor Awards. (all of them in this section)

North Carolina Film Critics Association.

Society of professional film critics in Oklahoma.

Columbus Film Critics Association. (Also Actor of the Year.)

San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle.

The Kansas City Film Circle.

North Dakota Film Society.

Denver Film Critics Society.

Online Film Critics Society.

Alliance of Women Film Journalists.

✧ TELOLW | Featurette - The Making Of.

7th ✧ TPOTD | Behind the Scenes with Legendary Director Jane Campion.

✧ Jane Campion talked about casting Benedict.

8th ✧ L.A. Times Actors Roundtable: Andrew Garfield, Benedict Cumberbatch, Oscar Isaac, Jared Leto, Javier Bardem & Peter Dinklage.

11th ✧ Benedict interview with W Magazine + Best Performances photoshoot. (Clip)

12th ✧ Benedict Cumberbatch, Claire Foy and Will Sharpe on new film TELOLW.

13th ✧ A new pic of Benedict training surfaced the internet!

✧ Podcast with Benedict recorded in Telluride, recently posted.

15th ✧ How Benedict Cumberbatch Made Phil Burbank Vulnerable | The Power of the Dog featurette.

18th ✧ Benedict Cumberbatch named the honoree of the Santa Barbara Film Festival’s Cinema Vanguard Award, presented next March 9.

19th ✧ Benedict Cumberbatch digs into toxic masculinity in TPOTD - Interview recorded for Fresh Air.

21st ✧ Benedict in a TPOTD special screening hosted by Tom Hiddleston. (event not available) Gallery 1, Gallery 2.

22nd ✧ Benedict Cumberbatch shares what it was like working with legendary director Jane Campion.

23rd ✧ TPOTD | Jane Campion & The Actors | Netflix

24th ✧ Q&A session with Will Sharpe, Benedict Cumerbatch, Claire Foy.

25th ✧ Reframing the West: Behind the Scenes of Jane Campion’s TPOTD.

✧ Benedict interview for Nihal Arthanayake show on BBC Radio 5.

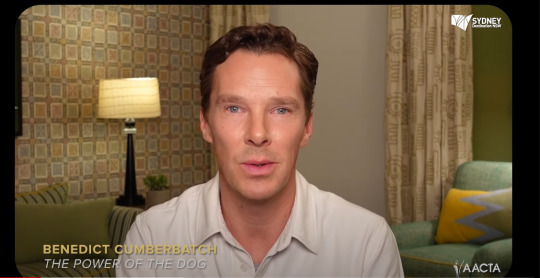

26th ✧ Benedict won the AACTA International Award for Best Lead Actor in Film for TPOTD.

Benedict acceptance speech.

27th ✧ Tom Holland Interviews Benedict Cumberbatch on TPOTD.

✧ TPOTD Cast and Artisans Discuss Bringing the Novel to Life for Variety.

28th ✧ Benedict on toxic masculinity, treasuring the BBC, and his new film TPOTD.

✧ Benedict and Penelope Cruz | Variety´s Actors on Actors.

30th ✧ Interview with Kevin McCarthy for FOX 5 Washington DC.

31st ✧ Benedict showed up unexpectedly in a screening in LA.

✧ New project announcement: Laura Dern, Noah Jupe & Benedict Cumberbatch To Star In Justin Kurzel Sci-Fi Drama ‘Morning’.

❯───「 FIN 」───❮

#benedict cumberbatch#benedictcumberbatchedit#benedict monthly#January 2022#the power of the dog#the electrical life of louis wain#Tom holland#Tom hiddleston#Claire foy#penelope cruz#wes anderson#long post#news#my post#happy New year of Benedict content!! woo!!

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Book No One Read

Why Stanislaw Lem’s futurism deserves attention.

I remember well the first time my certainty of a bright future evaporated, when my confidence in the panacea of technological progress was shaken. It was in 2007, on a warm September evening in San Francisco, where I was relaxing in a cheap motel room after two days covering The Singularity Summit, an annual gathering of scientists, technologists, and entrepreneurs discussing the future obsolescence of human beings.

In math, a “singularity” is a function that takes on an infinite value, usually to the detriment of an equation’s sense and sensibility. In physics, the term usually refers to a region of infinite density and infinitely curved space, something thought to exist inside black holes and at the very beginning of the Big Bang. In the rather different parlance of Silicon Valley, “The Singularity” is an inexorably-approaching event in which humans ride an accelerating wave of technological progress to somehow create superior artificial intellects—intellects which with predictable unpredictability then explosively make further disruptive innovations so powerful and profound that our civilization, our species, and perhaps even our entire planet are rapidly transformed into some scarcely imaginable state. Not long after The Singularity’s arrival, argue its proponents, humanity’s dominion over the Earth will come to an end.

I had encountered a wide spectrum of thought in and around the conference. Some attendees overflowed with exuberance, awaiting the arrival of machines of loving grace to watch over them in a paradisiacal post-scarcity utopia, while others, more mindful of history, dreaded the possible demons new technologies could unleash. Even the self-professed skeptics in attendance sensed the world was poised on the cusp of some massive technology-driven transition. A typical conversation at the conference would refer at least once to some exotic concept like whole-brain emulation, cognitive enhancement, artificial life, virtual reality, or molecular nanotechnology, and many carried a cynical sheen of eschatological hucksterism: Climb aboard, don’t delay, invest right now, and you, too, may be among the chosen who rise to power from the ashes of the former world!

Over vegetarian hors d’oeuvres and red wine at a Bay Area villa, I had chatted with the billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel, who planned to adopt an “aggressive” strategy for investing in a “positive” Singularity, which would be “the biggest boom ever,” if it doesn’t first “blow up the whole world.” I had talked with the autodidactic artificial-intelligence researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky about his fears that artificial minds might, once created, rapidly destroy the planet. At one point, the inventor-turned-proselytizer

Ray Kurzweil teleconferenced in to discuss,

among other things, his plans for becoming transhuman, transcending his own biology to

achieve some sort of

eternal life. Kurzweil

believes this is possible,

even probable, provided he can just live to see

The Singularity’s dawn,

which he has pegged at

sometime in the middle of the 21st century. To this end, he reportedly consumes some 150 vitamin supplements a day.

Returning to my motel room exhausted each night, I unwound by reading excerpts from an old book, Summa Technologiae. The late Polish author Stanislaw Lem had written it in the early 1960s, setting himself the lofty goal of forging a secular counterpart to the 13th-century Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas’s landmark compendium exploring the foundations and limits of Christian theology. Where Aquinas argued for the certainty of a Creator, an immortal soul, and eternal salvation as based on scripture, Lem concerned himself with the uncertain future of intelligence and technology throughout the universe, guided by the tenets of modern science.

To paraphrase Lem himself, the book was an investigation of the thorns of technological roses that had yet to bloom. And yet, despite Lem’s later observation that “nothing ages as fast as the future,” to my surprise most of the book’s nearly half-century-old prognostications concerned the very same topics I had encountered during my days at the conference, and felt just as fresh. Most surprising of all, in subsequent conversations I confirmed my suspicions that among the masters of our technological universe gathered there in San Francisco to forge a transhuman future, very few were familiar with the book or, for that matter, with Lem. I felt like a passenger in a car who discovers a blindspot in the central focus of the driver’s view.

Such blindness was, perhaps, understandable. In 2007, only fragments of Summa Technologiae had appeared in English, via partial translations undertaken independently by the literary scholar Peter Swirski and a German software developer named Frank Prengel. These fragments were what I read in the motel. The first complete English translation, by the media researcher Joanna Zylinska, only appeared in 2013. By Lem’s own admission, from the start the book was a commercial and a critical failure that “sank without a trace” upon its first appearance in print. Lem’s terminology and dense, baroque style is partially to blame—many of his finest points were made in digressive parables, allegories, and footnotes, and he coined his own neologisms for what were, at the time, distinctly over-the-horizon fields. In Lem’s lexicon, virtual reality was “phantomatics,” molecular nanotechnology was “molectronics,” cognitive enhancement was “cerebromatics,” and biomimicry and the creation of artificial life was “imitology.” He had even coined a term for search-engine optimization, a la Google: “ariadnology.” The path to advanced artificial intelligence he called the “technoevolution” of “intellectronics.”

Even now, if Lem is known at all to the vast majority of the English-speaking world, it is chiefly for his authorship of Solaris, a popular 1961 science-fiction novel that spawned two critically acclaimed film adaptations, one by Andrei Tarkovsky and another by Steven Soderbergh. Yet to say the prolific author only wrote science fiction would be foolishly dismissive. That so much of his output can be classified as such is because so many of his intellectual wanderings took him to the outer frontiers of knowledge.

Lem was a polymath, a voracious reader who devoured not only the classic literary canon, but also a plethora of research journals, scientific periodicals, and popular books by leading researchers. His genius was in standing on the shoulders of scientific giants to distill the essence of their work, flavored with bittersweet insights and thought experiments that linked their mathematical abstractions to deep existential mysteries and the nature of the human condition. For this reason alone, reading Lem is an education, wherein one may learn the deep ramifications of breakthroughs such as Claude Shannon’s development of information theory, Alan Turing’s work on computation, and John von Neumann’s exploration of game theory. Much of his best work entailed constructing analyses based on logic with which anyone would agree, then showing how these eminently reasonable premises lead to astonishing conclusions. And the fundamental urtext for all of it, the wellspring from which the remainder of his output flowed, is Summa Technologiae.

The core of the book is a heady mix of evolutionary biology, thermodynamics—the study of energy flowing through a system—and cybernetics, a diffuse field pioneered in the 1940s by Norbert Wiener studying how feedback loops can automatically regulate the behavior of machines and organisms. Considering a planetary civilization this way, Lem posits a set of feedbacks between the stability of a society and its degree of technological development. In its early stages, Lem writes, the development of technology is a self-reinforcing process that promotes homeostasis, the ability to maintain stability in the face of continual change and increasing disorder. That is, incremental advances in technology tend to progressively increase a society’s resilience against disruptive environmental forces such as pandemics, famines, earthquakes, and asteroid strikes. More advances lead to more protection, which promotes more advances still.

And yet, Lem argues, that same technology-driven positive feedback loop is also an Achilles heel for planetary civilizations, at least for ours here on Earth. As advances in science and technology accrue and the pace of discovery continues its acceleration, our society will approach an “information barrier” beyond which our brains—organs blindly, stochastically shaped by evolution for vastly different purposes—can no longer efficiently interpret and act on the deluge of information.

Past this point, our civilization should reach the end of what has been a period of exponential growth in science and technology. Homeostasis will break down, and without some major intervention, we will collapse into a “developmental crisis” from which we may never fully recover. Attempts to simply muddle through, Lem writes, would only lead to a vicious circle of boom-and-bust economic bubbles as society meanders blindly down a random, path-dependent route of scientific discovery and technological development. “Victories, that is, suddenly appearing domains of some new wonderful activity,” he writes, “will engulf us in their sheer size, thus preventing us from noticing some other opportunities—which may turn out to be even more valuable in the long run.”

Lem thus concludes that if our technological civilization is to avoid falling into decay, human obsolescence in one form or another is unavoidable. The sole remaining option for continued progress would then be the “automatization of cognitive processes” through development of algorithmic “information farms” and superhuman artificial intelligences. This would occur via a sophisticated plagiarism, the virtual simulation of the mindless, brute-force natural selection we see acting in biological evolution, which, Lem dryly notes, is the only technique known in the universe to construct philosophers, rather than mere philosophies.

The result is a disconcerting paradox, which Lem expresses early in the book: To maintain control of our own fate, we must yield our

agency to minds exponentially more powerful than our own, created through processes we cannot entirely understand, and hence potentially unknowable to us. This is the basis for Lem’s explorations of The Singularity, and in describing its consequences he reaches many conclusions that most of its present-day acolytes would share. But there is a difference between the typical modern approach and Lem’s, not in degree, but in kind.

Unlike the commodified futurism now so common in the bubble-worlds of Silicon Valley billionaires, Lem’s forecasts weren’t really about seeking personal enrichment from market fluctuations, shiny new gadgets, or simplistic ideologies of “disruptive innovation.” In Summa Technologiae and much of his subsequent work, Lem instead sought to map out the plausible answers to questions that today are too often passed over in silence, perhaps because they fail to neatly fit into any TED Talk or startup business plan: Does technology control humanity, or does humanity control technology? Where are the absolute limits for our knowledge and our achievement, and will these boundaries be formed by the fundamental laws of nature or by the inherent limitations of our psyche? If given the ability to satisfy nearly any material desire, what is it that we actually would want?

Lem’s explorations of these questions are dominated by his obsession with chance, the probabilistic tension between chaos and order as an arbiter of human destiny. He had a deep appreciation for entropy, the capacity for disorder to naturally, spontaneously arise and spread, cursing some while sparing others. It was an appreciation born from his experience as a young man in Poland before, during, and after World War II, where he saw chance’s role in the destruction of countless dreams, and where, perhaps by pure chance alone, his Jewish heritage did not result in his death. “We were like ants bustling in an anthill over which the heel of a boot is raised,” he wrote in Highcastle, an autobiographical memoir. “Some saw its shadow, or thought they did, but everyone, the uneasy included, ran about their usual business until the very last minute, ran with enthusiasm, devotion—to secure, to appease, to tame the future.” From the accumulated weight of those experiences, Lem wrote in the New Yorker in 1986, he had “come to understand the fragility that all systems have in common,” and “how human beings behave under extreme conditions—how their behavior when they are under enormous pressure is almost impossible to predict.”

To Lem (and, to their credit, a sizeable number of modern thinkers), the Singularity is less an opportunity than a question mark, a multidimensional crucible in which humanity’s future will be forged.

I couldn’t help thinking of Lem’s question mark that summer in 2007. Within and around the gardens surrounding the neoclassical Palace of Fine Arts Theater where the Singularity Summit was taking place, dark and disruptive shadows seemed to loom over the plans and aspirations of the gathered well-to-do. But they had precious little to do with malevolent superintelligences or runaway nanotechnology. Between my motel and the venue, panhandlers rested along the sidewalk, or stood with empty cups at busy intersections, almost invisible to everyone. Walking outside during one break between sessions, I stumbled across a homeless man defecating between two well-manicured bushes. Even within the context of the conference, hints of desperation sometimes tinged the not-infrequent conversations about raising capital; the subprime mortgage crisis was already unfolding that would, a year later, spark the near-collapse of the world’s financial system. While our society’s titans of technology were angling for advantages to create what they hoped would be the best of all possible futures, the world outside reminded those who would listen that we are barely in control even today.

I attended two more Singularity Summits, in 2008 and 2009, and during that three-year period, all the much-vaunted performance gains in various technologies seemed paltry against a more obvious yet less-discussed pattern of accelerating change: the rapid, incessant growth in global ecological degradation, economic inequality, and societal instability. Here, forecasts tend to be far less rosy than those for our future capabilities in information technology. They suggest, with some confidence, that when and if we ever breathe souls into our machines, most of humanity will not be dreaming of transcending their biology, but of fresh water, a full belly, and a warm, safe bed. How useful would a superintelligent computer be if it was submerged by storm surges from rising seas or dis- connected from a steady supply of electricity? Would biotech-boosted personal longevity be worthwhile in a world ravaged by armed, angry mobs of starving, displaced people? More than once I have wondered why so many high technologists are more concerned by as- yet-nonexistent threats than the much more mundane and all-too-real ones literally right before their eyes.

Lem was able to speak to my experience of the world outside the windows of the Singularity conference. A thread of humanistic humility runs through his work, a hard-gained certainty that technological development too often takes place only in service of our most primal urges, rewarding individual greed over the common good. He saw our world as exceedingly fragile, contingent upon a truly astronomical number of coincidences, where the vagaries of the human spirit had become the most volatile variables of all.

It is here that we find Lem’s key strength as a futurist. He refused to discount human nature’s influence on transhuman possibilities, and believed that the still-incomplete task of understanding our strengths and weaknesses as human beings was a crucial prerequisite for all speculative pathways to any post-Singularity future. Yet this strength also leads to what may be Lem’s great weakness, one which he shares with today’s hopeful transhumanists: an all-too-human optimism that shines through an otherwise-dispassionate darkness, a fervent faith that, when faced with the challenge of a transhuman future, we will heroically plunge headlong into its depths. In Lem’s view, humans, as imperfect as we are, shall always strive to progress and improve, seeking out all that is beautiful and possible rather than what may be merely convenient and profitable, and through this we may find salvation. That we might instead succumb to complacency, stagnation, regression, and extinction is something he acknowledges but can scarcely countenance. In the end, Lem, too, was seduced—though not by quasi-religious notions of personal immortality, endless growth, or cosmic teleology, but instead by the notion of an indomitable human spirit.

Like many other ideas from Summa Technologiae, this one finds its best expression in one of Lem’s works of fiction, his 1981 novella Golem XIV, in which a self-programming military supercomputer that has bootstrapped itself into sentience delivers a series of lectures critiquing evolution and humanity. Some would say it is foolish to seek truth in fiction, or to draw equivalence between an imaginary character’s thoughts and an author’s genuine beliefs, but for me the conclusion is inescapable. When the novella’s artificial philosopher makes its pronouncements through a connected vocoder, it is the human voice of Lem that emerges, uttering a prophecy of transcendence that is at once his most hopeful—and perhaps, in light of trends today, his most erroneous:

“I feel that you are entering an age of metamorphosis; that you will decide to cast aside your entire history, your entire heritage and all that remains of natural humanity—whose image, magnified into beautiful tragedy, is the focus of the mirrors of your beliefs; that you will advance (for there is no other way), and in this, which for you is now only a leap into the abyss, you will find a challenge, if not a beauty; and that you will proceed in your own way after all, since in casting off man, man will save himself.”

Freelance writer Lee Billings is the author of Five Billion Years of Solitude: The Search for Life Among the Stars.

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-book-no-one-read

Summa Technologiae https://publicityreform.github.io/findbyimage/readings/lem.pdf

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#GliSpiritidellisola #TAR e #EverythingEverywhereAllAtOnce si dividono i principali premi della San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle (#SFBAFCC): -Best Picture “The Banshees of Inisherin” Honorable Mention :“Everything Everywhere All at Once” -Best Director Todd Field, “TÁR” -Best Original Screenplay Todd Field, “TÁR” -Best Adapted Screenplay Sarah Polley, “Women Talking” -Best Actor Colin Farrell, “The Banshees of Inisherin” -Best Actress Cate Blanchett, “TÁR” -Best Supporting Actor Ke Huy Quan, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” -Best Supporting Actress (Tie) Kerry Condon, “The Banshees of Inisherin” Jamie Lee Curtis, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” -Best Animated Feature “Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio” -Best International Feature Film “Decision to Leave” -Best Documentary Feature “All That Breathes” -Best Cinematography Florian Hoffmeister, “TÁR” -Best Production Design Jason Isvarday and Kelsi Ephraim, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” -Best Film Editing Paul Rogers, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” -Best Original Score Hildur Guðnadóttir, “Women Talking” https://www.instagram.com/p/CnNDn2LMEgC/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Link

Another Best Actor nod for Andrew :-)

1 note

·

View note

Text

AUGUST 25: Bernice Bing (1936-1998)

The iconic artist and lesbian activist Bernice Bing passed away at the age of 62 on this day in 1998. Having made a name for herself on the San Francisco Bay Area art scene, Bernice became known for her “calligraphy-inspired abstractions” as well as for bringing a much-needed Chinese-American voice into LGBT activism.

A young Bernice Bing is photographed sitting in her art studio in her hometown of San Francisco, California (x).

Affectionately called Bingo by her friends, Bernice was born in 1936 in San Francisco, California’s Chinatown District. Her father was an immigrant from Southern China, but her mother had been born in America. After her mother’s death when Bernice was only 6-years-old, she and her sister were shifted around to different white foster homes in the city, only being exposed to their Chinese heritage briefly when they were allowed to live with their grandmother in Oakland from time to time. A poor student, Bernice developed a passion for drawing and the arts in high school. She would eventually attend California College of Arts and Crafts where she was introduced to Zen Buddhism and Chinese philosophers by a Japanese-born professor, Hasegawa, who would remain influential to her throughout her career.

Bernice Bing, Blue Mountain No.4 1965 (x).

After graduating, she became heavily involved in the circle of Beat writers and artists who lived and worked in the Bay Area such as Joan Brown, Wally Hedrick, and Fred Martin. In 1961, she was given a one-woman show at San Francisco’s Batman Gallery titled “Paintings & Drawings by Bernice Bing,” which received wide critical acclaim. In addition to her painting, Bernice was also present in existentialism circles, political activism, and arts administration. She created an art workshop in collaboration with a Chinatown gang called the Baby Wah Chings in response to the deadly shootings of the Golden Dragon Massacre in 1977 and became the first executive director of the South of Market Cultural Center (SOMArts) in 1980.

vimeo

Watch the trailer for The Worlds of Bernice Bing, directed by Madeleine Lim!

Bernice sadly passed away from cancer on August 25, 1998. Before her death, she became the first Asian-American artist to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Women's Caucus for Art and was also recognized by the Asian Heritage Council in 1990. The documentary The Worlds of Bernice Bing celebrating her life and legacy premiered at the Queer Women of Color Film Festival in 2013.

-LC

#365daysoflesbians#bernice bing#lesbian artists#chinese-american artists#lesbian history#wlw history#lgbt history#gay history#art history#lgbtq history#lesbian#wlw#sapphic#lgbt#lgbtq#gay#san francisco#usa#people#1950s#1960s

788 notes

·

View notes

Text

2021 Awards: San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle (SFBAFCC) Winners

2021 Awards: San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle (SFBAFCC) Winners

Best Picture – Nomadland Best Director – Chloé Zhao, Nomadland Best Original Screenplay – Lee Isaac Chung, Minari Best Adapted Screenplay – Kelly Reichardt, Jonathan Raymond, First Cow Best Actor – Chadwick Boseman, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom Best Actress – Frances McDormand, Nomadland Best Supporting Actor – Paul Raci, Sound of Metal Best Supporting Actress – Youn Yuh-jung, Minari Best…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Awards Season 2023-24: Awards Round-Up 1/15

The Oscar nominations are a week from tomorrow and the BAFTA nominations are Thursday. It’s crunch time. This week I’m covering a whopping 14 groups: African American Film Critics Association (AAFCA) Austin Film Critics Association (AFCA) Critics’ Choice Awards (CCA)/nominees DiscussingFilm Critic Awards (DFCA) Denver Film Critics Society (DFCS) Greater Western New York Film Critics…

View On WordPress

#2023 Films#2023 in Film#African-American Film Critics Association#Austin Film Critics Association#Awards Season 2023-24#Critics Choice Awards#Denver Film Critics Society#DiscussingFilm Critics Association#Film Awards#Greater Western New York Critics#Hawaii Film Critics Society#Hollywood Creative Alliance#Music City Film Critics Association#National Society of Film Critics#Portland Critics Association#San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle#Seattle Film Critics Society#Utah Film Critics Association

1 note

·

View note

Text

2024 San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle (SFBAFCC) Nominations

0 notes

Text

Prêmios e nomeações

- 7 vezes nomeado ao Oscar

- 1 Globo de Ouro - Grande Hotel Budapeste

- 1 BAFTA

- Writers Guild of America Award de Melhor Roteiro Original

- Urso de Prata de melhor diretor

- Gotham Independent Film Award de Melhor Filme

- Prêmio da Sociedade Nacional de Críticos de Cinema para Melhor Roteiro

- Prêmio David di Donatello de Melhor Filme Estrangeiro

- Prêmio Independent Spirit de Melhor Diretor

- New York Film Critics Circle Award de Melhor Roteiro

- MTV Movie Award: Melhor Diretor Novo

- San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle Award for Best Adapted Screenplay

- Los Angeles Film Critics Association New Generation Award

0 notes

Text

Characters in the movie: “Jobs”

Jobs is a 2013 American biographical drama film based on the life of Steve Jobs, from 1974 while a student at Reed College to the introduction of the iPod in 2001. It is directed by Joshua Michael Stern, written by Matt Whiteley, and produced by Stern and Mark Hulme. Steve Jobs is portrayed by Ashton Kutcher, with Josh Gad as Apple Computer's co-founder Steve Wozniak. Jobs was chosen to close the 2013 Sundance Film Festival.

Who’s Who in the film?

Apple Ashton Kutcher as Steve Jobs: Steven Paul Jobs is widely recognized as a pioneer of the microcomputer revolution of the 1970s and 1980s, along with Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak. Jobs was born in San Francisco, California and put up for adoption. He was raised in the San Francisco Bay Area.

JOBS WAS AWARDED OVER 450 PATENTS AS HE REVOLUTIONIZED SIX MAJOR INDUSTRIES

Steve Jobs’ ability to visualize, conceptualize and deliver path breaking products through his team and companies took the world aback and made everyone take notice. During his lifetime of work as a creative entrepreneur he focused on the “look and feel“ of his products and aspired for perfection in design. He was awarded close to 450 patents ranging from computers, touch based interfaces, keyboards, portables to staircases, clasps and sleeves. Along the way he revolutionized six industries: personal computers, animated movies, music, phones, tablet computing and digital publishing.

Read more about Steve Jobs: https://learnodo-newtonic.com/steve-jobs-achievements

Josh Gad as Steve Wozniak: Stephen Gary "Woz" Wozniak is an American inventor, electronics engineer, programmer, philanthropist, and technology entrepreneur. In 1976 he co-founded Apple Inc., which later became the world's largest information technology company by revenue and largest company in the world by market capitalization. He and Apple co-founder Steve Jobs are widely recognized as two prominent pioneers of the personal computer revolution of the 1970s and 1980s.

Lukas Haas as Daniel Kottke: Daniel Kottke was a college friend of Steve Jobs and one of the first employees of Apple Inc.

Victor Rasuk as Bill Fernandez: Bill Fernandez is a user-interface architect and inventor who was Apple Computer's first employee when after incorporated in 1977 and is, overall, Apple employee #4. He is the son of Judge Bill Fernandez and Bambi Fernandez (both Stanford University graduates). He worked on both the Apple I and Apple II personal computers, and in the 1980s was a member of the Apple Macintosh development team. He contributed to several user interface aspects of the classic Mac OS, QuickTime and HyperCard and owns a user interface patent granted in 1994. He is also credited with introducing fellow Homestead High School student Steve Jobs to his friend (and Homestead alumn) Steve Wozniak. Eddie Hassell as Chris Espinosa: Chris Espinosa is a senior employee of Apple Inc., officially employee number 8. Having joined the company at the age of fourteen in 1976 when it was still housed in Steve Jobs' parents' garage, writing software manuals and coding after school, he is the company's current and all-time longest-serving employee. Ron Eldard as Rod Holt: Frederick Rodney Holt is an American computer engineer and political activist. He is Apple employee #5, and developed the unique power supply for the 1977 Apple II.

Nelson Franklin as Bill Atkinson: Bill Atkinson is an American computer engineer and photographer. Atkinson worked at Apple Computer from 1978 to 1990. Atkinson was the principal designer and developer of the graphical user interface (GUI) of the Apple Lisa and, later, one of the first thirty members of the original Apple Macintosh development team, and was the creator of the ground-breaking MacPaint application, which fulfilled the vision of using the computer as a creative tool. He also designed and implemented QuickDraw, the fundamental toolbox that the Lisa and Macintosh used for graphics.

Elden Henson as Andy Hertzfeld: Andy Hertzfeld is an American computer scientist and inventor who was a member of the original Apple Macintosh development team during the 1980s. After buying an Apple II in January 1978, he went to work for Apple Computer from August 1979 until March 1984, where he was a designer for the Macintosh system software. Since leaving Apple, he has co-founded three companies: Radius in 1986, General Magic in 1990, and Eazel in 1999. In 2002, he helped Mitch Kapor promote open source software with the Open Source Applications Foundation. Hertzfeld worked at Google from 2005 to 2013, where in 2011 he was the key designer of the Circles user interface in Google+.

Lenny Jacobson as Burrell Smith: Burrell Carver Smith is an American engineer who, while working at Apple Computer, designed the motherboard (digital circuit board) for the original Macintosh. He was Apple employee #282, and was hired in February 1979, initially as an Apple II service technician. He also designed the motherboard for Apple's LaserWriter.

Giles Matthey as Jony Ive: Jony Ive is one of the world’s most esteemed industrial designers and has worked on products, including a wide range of Macs, the iPod, iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, and more. He also had a hand in designing the company’s “spaceship” Apple Park campus and establishing the look and feel of Apple retail stores.

Dermot Mulroney as Mike Markkula: Armas Clifford "Mike" Markkula Jr. is an American electrical engineer, businessman and investor. He was an angel investor and second CEO of Apple Computer, Inc., providing early critical funding and managerial support. Markkula was introduced to Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak when they were looking for funding to manufacture the Apple II personal computer they had developed, after having sold some units of the first version of this computer, the Apple I. With his guidance and funding, Apple ceased to be a partnership and was incorporated as a company.

Matthew Modine as John Sculley: John Sculley III (born April 6, 1939) is an American businessman, entrepreneur and investor in high-tech startups. Sculley was vice-president (1970–1977) and president of Pepsi-Cola (1977–1983), until he became chief executive officer (CEO) of Apple Inc. on April 8, 1983, a position he held until leaving in 1993. In May 1987, Sculley was named Silicon Valley's top-paid executive, with an annual salary of US$10.2 million.Sales at Apple increased from $800 million to $8 billion under Sculley's management.

J. K. Simmons as Arthur Rock: Arthur Rock is an American businessman and investor. Based in Silicon Valley, California, he was an early investor in major firms including Intel, Apple Computer, Scientific Data Systems and Teledyne.

Kevin Dunn as Gil Amelio: Gilbert Frank Amelio is an American technology executive. Amelio worked at Bell Labs, Fairchild Semiconductor, and the semiconductor division of Rockwell International but is best remembered as a CEO of National Semiconductor and Apple Inc.

Brett Gelman as Jef Raskin: Jef Raskin was an American human–computer interface expert best known for conceiving and starting the Macintosh project at Apple in the late 1970s.

Family John Getz as Paul Jobs. Steve Jobs father.

See: https://allaboutstevejobs.com/bio/key_people/paul_jobs

Lesley Ann Warren as Clara Jobs. Steve Jobs mother. See: https://g.co/kgs/AC8BCR

Abby Brammell as Laurene Powell Jobs: Laurene Powell Jobs has become an influential and formidable presence in the investing world. And she ranks among the richest women in the world, with a net worth of $21.3 billion, according to Forbes. Upon her husband's death in 2011, Powell Jobs inherited his fortune — primarily shares of Apple and Disney.

Ahna O'Reilly as Chrisann Brennan: Chrisann Brennan is an American painter and writer who wrote the autobiography The Bite in the Apple about her relationship with Apple co-founder Steve Jobs. They had one child, Lisa Brennan-Jobs.

Annika Bertea as Lisa Brennan-Jobs (adult) Ava Acres as Lisa Brennan (child)

Other James Woods as Jack Dudman: Jack Dudman was a much-loved math professor and later dean of students at nearby Reed College.

David Denman as Al Alcorn: Allan Alcorn is an American pioneering engineer and computer scientist best known for creating Pong, one of the first video games.

Brad William Henke as Paul Terrell: Paul Terrell: Owned local computer store and was an original investor in Jobs and Wozniak’s very first big idea.

Robert Pine as Edgar S. Woolard, Jr.: Edgar S. Woolard Jr. is an American businessman. He was chairman and chief executive officer of DuPont from 1989 to 1995.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 49. Second Anniversary

Let’s start with the destination: New Zealand. Again.

Yes, this is our third time here in just 8 months, but what can I say: it’s a great country. Actually, I’m not sure any country better reflects Chelsay and I than New Zealand. The US seems angry these days, Asian cultures are a bit rigid, and Europe… Please. But New Zealand: adventurous, easy going, and a sense of humor. That’s Chelsay and I in a nutshell!

New Zealand is the geographic embodiment of Chelsay and I’s relationship, and that’s why it’s the perfect place to celebrate our second anniversary.

Now, my last post ended with a teaser for our return to the UK, but that’s turned into a longer process than expected. In the words of my boss: “No country moves slower than the UK.” ...Yep, I remember.

That doesn’t mean Chelsay and I have been idle though. A few bullets on our past two months in limbo:

We discovered our “Richmond Park” equivalent, with weekend walks up the Northern Beaches: Freshwater, Curl Curl, and Dee Why.

I had a quick work trip to San Francisco. I can’t even remember the business purpose – I think it was to recreate scenes from Vertigo.

Chelsay and I finally explored some famous Sydney neighborhoods we hadn’t visited, Palm Beach and Watson’s Bay.

We ran the City 2 Surf, along with 80,000 other Sydneysiders.

We started horse riding. This has been a dream of Chelsay’s for a while, and that enthusiasm shows in her riding: through just three lessons, she’s already trotting with ease. Meanwhile, Mike is a bit behind, though in fairness, I’m at a disadvantage. The stable’s typical clientele is primarily young girls (not a lot of 30 year old men learning to ride), so they only have one horse for someone my size, Jazz. One problem: Jazz is blind in one eye. While Chelsay is trotting in circles around the arena, I’m battling a blind horse to avoid running into a wall.

Chelsay nearly burned the house down while cooking. We can laugh about it now, but at the time: this was catastrophic. I’ll just say that the situation required me to burst out of the shower to help.

Anyway, we’ve stayed busy, and after a demanding few months at work, we were ready for a vacation. Our September anniversary falls in winter in the Southern Hemisphere, so Chelsay and I decided we’d take advantage by making this year’s celebration a ski trip. Crisp air and hot chocolate: very romantic.

New Zealand has two hubs for skiing: Queenstown and Wanaka. They’re fairly close to one another but are drastically different. Queenstown is beautifully set below The Remarkables, but can feel a bit crowded in peak season. On the other hand, Wanaka has an equally beautiful setting, but is much quieter and basically only has one street. Ultimately we went with Wanaka because we’re old people… and also because it’s closer to Treble Cone, whose advanced runs better suited Chelsay & I’s “gnar shredding”.

We arrived late on the first day, driving through some beautiful yet brooding landscapes.

We got really lucky with our hotel. I’d mentioned that we were celebrating our anniversary, and they upgraded us to a suite. The extra space was critical after long days on the pistes. One side note on the hotel room: while Chelsay and I were enjoying our Night 1 chacuterie, we had a strange feeling: we were in shorts. Indoors. And not freezing… Why did it feel so strange? My god, is this what it’s like to be… warm!? It was tangibly strange to us to feel warm! Our Sydney apartment had been so consistently cold all winter, that we were genuinely perplexed with a temperature about 55. Suite life got this trip off to a hot start.

The next day we hit the slopes. Treble Cone doesn’t have any accommodation, so it’s a short, steep, unpaved, cliff-side, and overall just treacherous drive up from Wanaka. We felt like we were on double black diamond runs before we even arrived.

After surviving the ride up, we geared up and took one “Welcome Back” practice run on the bunny hill. I’m very surprised by this fact: it had been FOUR years since the last time Chelsay and I skied (Austria in 2015). That’s the same amount of time it’d been between Innsbruck and the time before (Whistler in 2011). You might remember that we were RUSTY in Innsbruck, with Day 1 highlights including Chelsay being dragged up the bunny hill by the rope pulley as five-year old Austrian children looked on. Another Innsbruck gem: once on the real slopes, Chelsay and I failed to disembark the gondola on time. As the lift turned away from the dismount area, I leapt off the chair and crash landed on the slope below. I yelled back to Chelsay: “You gotta bail!”, but she refused. She would’ve been content riding the gondola all the way back down, had the large Austrian attendant not forcibly picked her from the chair and set her on the snow.

Luckily we weren’t as rusty in Wanaka. We successfully managed the bunny hill rope-pulley, and dismounted the chair lifts at the appropriate time.

That said, we found a new hiccup this time around.To get to the chair lift, you have to present your lift pass. Treble Cone uses RFID lift passes, so all you do is ski up to the gate, it reads your pass, and you ski through. Think of a toll tag. Not that hard right – you just have to be in control for the gate to read your pass. Well, Chelsay was not in control, and went screaming up to the gate, smashed right through the barrier. I was actually impressive that she kept her balance and skied on, unscathed. The same cannot be said for the broken barrier.

Once at the top of the mountain, the views were breathtaking. Most ski resorts are surrounded by snow-capped peaks – this will always be an incredible sight. But Treble Cone’s views are more diverse: sure, there are snow-capped peaks, but you can also see the stark, undulating landscape surrounding Lake Wanaka. It makes Treble Cone one of the most unique and beautiful ski resort we’ve visited.

The slopes matched the views, with a mix of wide, well-groomed runs where you can get some speed, but also steep & narrow runs that require a bit more technique. As a quick aside, Chelsay’s technique is best described as “clench”. She torched her thighs bracing down the slope, cutting sharply on each turn. It’s so easy to pick her out from the crowd. Rather than slide across the snow, occasionally using friction to slow down, it looked like she was using her skis to carve a path down the mountain.

This was payback for her horse-riding prowess. While she metaphorically “rode a blind horse”, I was bombing blue runs in no time. I brought Chelsay along on one, but she was convinced they were black diamonds. I remember her turning to me and saying in terror, “I shouldn’t be on this one.”

Chelsay may not be as enthusiastic about skiing, but I love it. I rarely slow down – if you traced our routes, Chelsay’s would look like an ‘S’, but mine would be and “I”. I actually wish I had an Apple Watch to capture my max speed. At the end of each run, my teeth were cold from smiling the whole way down.

By Day 2, I was on some really challenging red runs, battling moguls on steep, ungroomed slopes. Meanwhile, Chelsay was improving too. She’d loosened her “clench” a bit and was getting more and more comfortable at speed. In fact, on our last run of Day 2 (dubbed ‘the poop shoot’ by Chelsay), I secretly led her down a red run. She did great! But also collapsed from exhaustion at the bottom of the run.

Chelsay’s legs were shot for our third and last day of skiing, so we only got half day passes at Cadrona, a less challenging resort than Treble Cone. That said, Cadrona does have a terrain park, so the resort gets a weird mix of graceful Olympians and awkward amateurs. While the pros were busting 1080s in the halfpipe, I saw one guy get run over while waiting for the chair lift. This is how I must’ve looked in Austria.

Like Treble Cone, Cadrona has great views of the surrounding Southern Alps. We managed a few solid morning runs, but decided to save our already worn-out legs for the afternoon’s activity: horse riding.

Although Chelsay & I were barely capable of trotting, we’d heard New Zealand was one of the best places in the world for horse riding. It’s quiet, crisp, and secluded, yet you’re riding through pristine landscapes: glacial rivers, evergreen forests, and mountainous valleys. Its so beautiful that the stable we booked, High Country Horses in Glenorchy, lends their horses to the dozens of movies filmed nearby: Lord of the Rings, X-Men, Vertical Limit, Chronicles of Narnia… Our guide was riding Tom Cruise’s horse in Mission Impossible Fallout.

The ride itself lived up to its Hollywood billing. First, the setting was cinema worthy. Second, my horse wasn’t blind, so I was able to trot with ease. Third, Chelsay was in heaven. We wrapped up our ride just as the sun fell below the Southern Alps.

It was an eventful day in which we started on the slopes and ended on horseback. Luckily, Chelsay & I were near Taj, the Indian restaurant we’d gone to the last time we were this ravenous in New Zealand. In January, we took Taj to-go after hiking Gertrude Saddle, enjoying the garlic naan, hearty daal, and spicy murg chettinad curry while watching the Hobbit from our warm AirBnB. For Round 2, we ran back the exact same order – it somehow was even better. Its hard for me to admit this because I love Dishoom in London, but Taj is the best Indian restaurant I’ve ever been to.

I just realized that I’ve skipped over the meals in this post, so I want to come back to a couple we really enjoyed. First, at the Cadrona Hotel, Chelsay’s Beef Wellington was her dream savory dish: a juicy steak coated in buttery pastry. She made British Bake Off commentary the whole meal. We also gorged ourselves with a Fergberger lakeside in Queenstown, and enjoyed pumpkin risotto and lamb ragu at our old favorite in Wanaka, Francescas. Finally, even the quick breakfasts we grabbed before skiing were tasty: Chelsay and I would take our chicken & corn pie and bacon & egg sandwich from The Doughbin and eat by Lake Wanaka. Guess who ordered each dish.

Now, a lot of these restaurants were repeats from previous trips: Taj, Cadrona Hotel, Fergberger, Francescas. As I said at the start of the post, New Zealand itself is a repeat for Chelsay and I. But these recurrences are fitting for an anniversary, and I am so thankful to repeat every day, week, month, and year with Chelsay as my wife.

Much like our trips to New Zealand, each anniversary with her is perfect no matter how many times we repeat.

0 notes

Photo

WELCOME TO SUMMERTIME IN SAN FRANCISCO ( JULY EDITION )!

It’s finally and officially summer and we found some spectacular events for you all to go to. As per usual, every time you go with a partner somewhere listed below you both receive $100. So, grab a partner and enjoy the outdoors!

The Toxic Avenger: Based on Lloyd Kaufman's cult film and winner of the Outer Critics Circle Award for Best Off-Broadway Musical, The Toxic Avenger is a charming love story and laugh-out-loud musical that has it all: an unlikely hero, his beautiful girlfriend, a corrupt New Jersey mayor and two guys who play... well, everyone else ... bullies, mobsters, old ladies and stiletto-wearing back up singers. With book and lyrics by Joe DiPietro and music and lyrics by David Bryan, the show also features the most memorable and unbelievable duet you'll ever see on any stage. ( July 1st - July 16th / Times Vary )

The 33rd Annual Fillmore Jazz Festival: Blending art and soul in one of the country’s most unique neighborhoods, the Fillmore Jazz Festival is the largest free Jazz festival on the West Coast, drawing over 100,000 visitors over the Independence Day weekend. From sunup to sundown, visitors can groove to the sounds of live music from multiple stages, browse the offerings of over 12 blocks of fine art and crafts and enjoy gourmet food and beverages. ( July 1st & 2nd / 10am - 6pm )

The PIER’s 4th of July Celebration: Witness the skies sparkle red, white and blue as PIER 39 celebrates Independence Day with a day of fun for the whole family! Rock out to live music by WJM on the Entrance Plaza Stage at 12:30pm, followed by the Bay Area’s favorite cover band Tainted Love – The Best of the 80s Live! at 5pm. At 9:30pm, look to the sky for the City & County of San Francisco’s spectacular fireworks display. ( July 4th / Times Vary )

Fourth of July Fireworks Cruise: Departing from Pier 43 ½, join Red and White Fleet for a brief cruise along San Francisco’s illuminated skyline in the early evening. With views of Alcatraz Island and the Golden Gate Bridge in the distance, we’ll position near the location of the fireworks to ensure best possible views for all guests aboard. ( July 4th / 7:45 & 8:15pm )

How-To: Survival NightLife: Adventure Out: the Bay Area’s oldest wilderness survival school, will demonstrate essential tips to help you think on your feet while far from civilization. ( July 6th / 6pm - 10pm ) Guide to Exploration: Learn from the masters at Twisted Thistle Apothecary about topical medicinal plants you can use to help ease rashes, bites and burns and learn the ones you should avoid. ( July 6th / 6pm - 10pm )

House Party at Powerhouse Bar: The furniture and rugs get moved back in for the best frat infused underground dance party! Ky and Juan Martinez give you a laser light show, Mohammad Vahidy puts on the beats! ( July 8th / 9pm - 2am )

Flower Piano: Flower Piano is a special 12–day long community event from July 13-24 only, where 12 pianos are placed at dramatic, picturesque locations throughout the Garden's 55 acres for anyone to play. All 12 pianos will be available for the public between 9am and 6pm each day, except during performances. ( July 13th - July 24th / Times Vary )

Film Night in the Park: Film Night in the Park is San Francisco's premiere outdoor film series. Over 125,000 people have attended Film Night in San Francisco since 2003. Films are presented free of charge on a giant outdoor screen in beautiful park settings. Movie: Beauty and the Beast. ( July 15th / @ Dusk )

Pixar in concert with live orchestra: From Toy Story to Finding Nemo, Pixar films have given audiences of all ages some of the most beloved characters on screen. This summer, Pixar in Concert offers musical selections from box office hits like Ratatouille, Monsters University, and Up, performed live by the San Francisco Symphony while clips are projected on the big screen. Fun for the entire family. ( July 15th - July 16th / 7pm & 2pm )

Beer Garden NightLife: Every beer tells a story—and this week—NightLife follows the brewing process from botanical inception to foamy finish. Hear from local beer and spirit masters, chat with flora-connoiseurs from the SF Botanical Garden, and drink your way through a pop-up beer garden with a dozen of local breweries. ( July 20th / 6pm - 9:45pm )

Orchids in the Park: Join us for Orchids in the Park, our summer show and sale. View orchids on display from local growers and purchase plants and supplies from vendors from all over the world. ( July 22nd - July 23rd / 10am - 5pm )

San Francisco Frozen Film Festival: The San Francisco Frozen Film Festival (SFFFF) is a Nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization founded in 2006 that is dedicated to creating avenues for independent filmmakers, filmmakers of conscience, and artists from underserved communities to come together and exhibit their work to the widest possible audience. ( July 22nd - July 23rd / Times Vary )

The San Francisco Marathon: This year marks the 40th edition of the San Francisco Marathon! Spend your Sunday morning touring SF's streets with your own feet by joining more than 27,000 other runners in either the 5K, half, or full marathon. You'll run past landmarks like the Embarcadero, Fisherman's Wharf, Crissy Field, the Golden Gate Bridge, Coit Tower, Golden Gate Park, the Haight-Ashbury, and the Mission. ( July 23rd / Times Vary )

Up Your Alley: NSFW - Up Your Alley® is only for real players – and not for the faint of heart – where leather daddies rule the streets of San Francisco’s South of Market district. Of course, if rubber, sportswear, biker gear, skinheads, punks, or any variety of built, hairy men turns you on, then we’ve got it. You won’t find a filthier event in the States. If you’re into it, there’s a scene for you. So, don’t get left out. ( July 30th / 11am - 6pm )

4 notes

·

View notes