#SAWG WE NEED TO DO BETTER

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In light of Timotjdéhéëéh chwjsjajebet being zio the gf and I are forced to turn our post finals date movie into Napoleon (2023) I've never been so afraid

#SAWG WE NEED TO DO BETTER#zuggesting red cliff 2008 be tbthats not really a date movie either#portrait iof a lady on fire. in firr?#soery dor the bunch of personal posts man im a bit crazy#grapeposting

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

unfiltered first reactions to gpi as if i were livetweeting because i think it would be funny (spoilers below!!):

are these 12 year olds or do they just talk like that.

can i touch it, dawg WHAT

dont even know their names but i already love em and only want happiness for them (may be because they strike me as children) (update they were children)

why did bro bite his hand

WHERES THE OTHER BED GOING. NO. HOSPITAL?? NO!! NOT AGAIN :SOB:

i need subtitles oh my god,,,ADULTS NOW!! i see. doug. theyre in suits and he has a bandage yall boutta kiss rn?? OHHH FUCK ohhh oh man. boutta be so fucking sick over doug aw shit

"his name is assface!" oh babe.

"you know." oh BABE. oh fuck.

think about what all the time???????????????? THINK ABOUT WHAT??????????

this is so 'are they lovers' 'worse' and nothings even happened but so much has happened.

ooooh five years

corey. THEY KISSED(before)!!! FUCK!!! MISSING TOOTH!!!

this hurts ohmy god. screaming. theyre gone.

two beds again?? are we flitting between times. 13 ahh yes we are oh i love this so much. what if i hit corey with the autism beam. what then. doug is so me im gonna lose my mind. like when theyre kids. auughh

DO YOU WANNA PRACTICE KISSING?/ SAWG???god thats the gayest shit ever. everyone who says that never means it casually change my goddamn mind YOU CANT/lh doug fucking w first kiss logic is hilarious yes king.

oh my god hes throwing up. DOUG NOO AHAHAH. fellas is it gay to throw up in the same can after kissing.

augh one bed again OUGH HOSPRIALo ohh no. 28. dont do this to me. not after falsettos.

hey again! hes not responding. kms. NOO IS HE IN A COMA OH FUCK

"im trying not to swear so much" giggled

"her"?? dawg no way THEY HAVENT SEEN EACHOTHER SINCE HIS EYE??? oh fuck me man. babe stop saying rtrded please. hes moisturizing his fucking hand oh. MY GOD.

you cant marry her cuz what about me?? SAY YOU LOVE HIM ALREADY FUCK

OOO TWO BEDS. THEYRE CLOSER!!!! ONE BLANKET!! OOOOO!!

18 fuckin called it. 10 yrs ago. thin mints slap hes so real for that. the knocking on his cup shouldnt have tbeen that funny. giggled. okay theyre so besties but like this is so gay. bestie behavior but. they love eachother. (doug is mad about not knowing that corey's been having sex, which like id be upset if my bestie didnt tell me too i get it but correct me if im wrong, this feels insanely jealous

"cuz youre too youung!" YOURE FUCKING EIGHTEEN???

im so sick over doug HES SO ME FUCK ok fuck.

im so. insane. fuck. "whys everyone gotta be so mean?"

"youre not a faggot. youre not" ohhh ow. oh oh my god

okau so when he says :you have blood on your jeans. when did you start [that]: i cant make out what he says or what theyre talking about im assuming its sh??? if so?? fucking ow kill me??????

timing of me watching this. fucking wild. did not want to cry tn (im not but were dangerously close to it)

I CAN NOT FUCKING DO THIS OH GOD

milo when i get you. milo when i fucking. get you./lh

"youre the best thing thats ever happened to me" after THAT?? FUCK ME MAN WHAT THE HELL

he better be fucking awake or i swear to god.

33 OH FUCK MANHES HAWAKE HES AWAKE OH FUCK OH THANK GOD. FIVE YEARS AGO/?? COREY VISTED HIM FIVE YEARS AGO. is he in a mental hospital?? oh boy. these boys are fucked up.

theyre fucking soulmates. i will NOT be taking criticism. WHY ARE YOU LYING YOU BEGGED HIM TO WAKE UP ASSHOLE. doug makes me want to hold my own heart in my hands and feel it beat. dawg why u lying.why is corey mean to him :(

ohh parallels. oh they. hurt. differenty. but the same. ohhhh my god

"because i might not make it back"

if one of them fucking dies. i stg. 23 10 yrs back. wait this is the first bit again/? WHAT HAPPENED TO YOUR TOOTH. DUDE. OH FUCK.

criyng at dougs speech after the kiss.

oh fuck OFF. only the poster wtf

i need the playlist they got. 38,,,

i went "hes fucking dead isnt he" and he rolls in. "im gonnakms"

"dont touch me corey" sobbing.

pleading with my screen for it not to end like that and its over.

milo. oh my fucking god

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good to know! I've used yeast nutrients in my modern meads, but I'll try fruit juice for my traditional brews. I've also heard orange juice works well. The short fermentation time is pretty common in the medieval recipes, funnily enough. Others list "ten weeks," and later, more early modern recipes tend to understand the need to let mead age for at least a month. "Immediately after the recipe for metheglin in MS.MSL.136, there is a recipe for “clarey” (a spiced and sweetened wine used recreationally to aid digestion), which is followed by one fora fruited mead (a style called melomel in modern mead making).

This recipe reads:

An other gode drynke boile x galons of clere watir and a galon of honey iij howres and skymme it wele and kest in iiij galons of damysyns or of chires and boyle as longe as then put there to ij unces of powdir of rosemary and as moch powdyr off sawge and when itt is cold clene it and twne it in a barell opon a galon of good reede lyes that bene new and there in a small clout an unce of powdyr of galyngalle and half an unce of powdir of canell and stop it fast that noon eyr go owto and lett it stand so x wekes or xij and than broch it iff thou wilt to. (f.22v)"

My guess is that since water was less-than-clean, shortly-fermented mead was a safer, low-alcohol alternative, but this is conjecture. Since we have so few records, it may be a matter of "one recipe for this, another for that" with different techniques/times for different ABV content.

Boiling the honey nowadays is definitely not recommended, but even these 15th century bochet recipes from the Good Wife's Guide recommend boiling, and even replacing the water content lost from skimming, too. (This recipe is aged for months.)

Bochet. To make 6 septiers of bochet, take 6 quarts of fine, mild honey and put it in a cauldron on the fire to boil. Keep stirring until it stops swelling and it has bubbles like small blisters that burst, giving off a little blackish steam. Then add 7 septiers of water and boil until it all reduces to 6 septiers, stirring constantly. Put it in a tub to cool to lukewarm, and strain through a cloth. Decant into a keg and add one pint of brewer's yeast, for that is what makes it piquant - although if you use bread leaven, the flavor is just as good, but the color will be paler. Cover well and warmly so that it ferments. And for an even better version, add an ounce of ginger, long pepper, grains of paradise, and cloves in equal amounts, except for the cloves of which there should be less; put them in a linen bag and toss into the keg. Two or three days later, when the bochet smells spicy and is tangy enough, remove the spice sachet, wring it out, and put it in another barrel you have underway. Thus you can reuse these spices up to 3 or 4 times (Greco and Rose, 2009, p.325).

Item, another bochet which keeps for four years, and you can make a whole queue [barrel or cask, also a unit of measure] or more or less at one time if you wish. Combine three parts water and a fourth part honey, boil and skim until reduced by a tenth, and then pour into a container. Refill the cauldron and do the same again, until you have the amount you want. Let it cool and then fill a queue. The bochet will then give off something like a must that will ferment. Keep the container full so that it keeps fermenting. After six weeks or seven months [?], you must draw out all the bochet, up to the lees, and put it in a vat or other vessel. Then break apart the first container and remove the lees. Scald it, wash it, reassemble it, and fill with the liquid you set aside, and store it. It does not matter if it is tapped. Crush four and a half ounces of clove and one grain of paradise, put in a linen bag, and hang inside the keg by a cord from the bung. Nota For each pot of foam skimmed off, add twelve pots of water and boil together: this will make a nice bochet for the household staff. Item, using other honey rather than the skim, make it the same proportions (Greco and Rose 2009, p.325-6).

Meadmaking, Pt. 2

Hi again, more mead-making shenanigans! This time, more medieval.

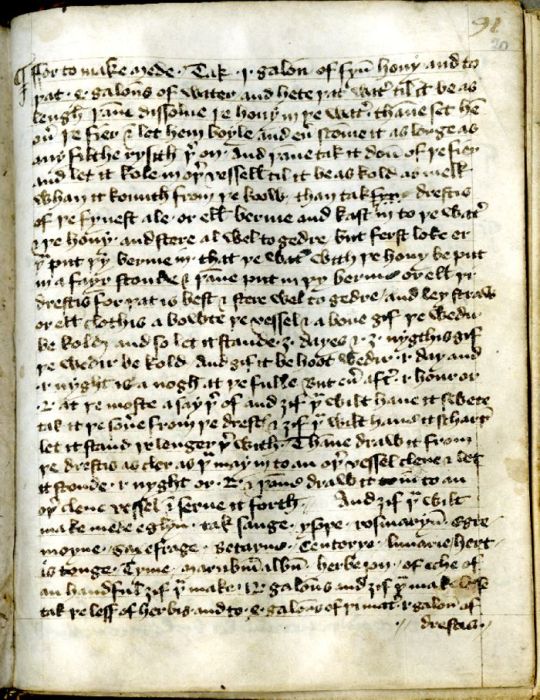

I'm going to highlight one particular recipe - the oldest English one we have. This comes from Tractatus de Magnetate et Operationibus eius (the thirteenth-century letter on the magnet by Petrus Peregrinus) (Folio 20r). You can read the original here.

It's a weird place for a mead recipe, that's for sure, but I won't complain.

Here's the transliteration:

ffor to make mede. Tak .i. galoun of fyne hony and to þat .4. galouns of water and hete þat water til it be as lengh þanne dissolue þe hony in þe water. thanne set hem ouer þe fier & let hem boyle and ever scomme it as longe as any filthe rysith þer on. and þanne tak it doun of þe fier and let it kole in oþer vesselle til it be as kold as melk whan it komith from þe koow. than tak drestis of þe fynest ale or elles berme and kast in to þe water & þe hony. and stere al wel to gedre but ferst loke er þu put þy berme in. that þe water with þe hony be put in a fayr stonde & þanne put in þy berme or elles þi drestis for þat is best & stere wel to gedre/ and ley straw or elles clothis a bowte þe vessel & a boue gif þe wedir be kolde and so let it stande .3. dayes & .3. nygthis gif þe wedir be kold And gif it be hoot wedir .i. day and .1. nyght is a nogh at þe fulle But ever after .i. hour or .2. at þe moste a say þer of and gif þu wilt have it swete tak it þe sonere from þe drestis & gif þu wilt have it scharpe let it stand þe lenger þer with. Thanne draw it from þe drestis as cler as þu may in to an oþer vessel clene & let it stonde .1. nyght or .2. & þanne draw it in to an oþer clene vessel & serve it forth //And gif þu wilt make mede eglyn. tak sauge .ysope. rosmaryne. Egre- moyne./ saxefrage. betayne./ centorye. lunarie/ hert- is tonge./ Tyme./ marubium album. herbe jon./ of eche of an handful gif þu make .12. galouns and gif þu mak lesse tak þe less of herbis. and to .4. galouns of þi mater .i. galoun of drestis.

Super clear, right? Here's a modern English version:

For to make mead. Take 1 gallon of fine honey, and to that 4 gallons of water and heat that water till it be as lengh then dissolve the honey in the water. Then set them over the fire and let them boil and scum it as long as any filth rises thereon. And then take it down off the fire, and let it cool in another vessel till it be as cold as milk when it comes from the cow. Then take dregs of the finest ale or else barm and cast it into the water and the honey. And stir it all well together, but first look ere you put your barm in that the water with the honey be put in a fair stonde and then put in your barm or else your dregs for that is best and stir well together; and lay straw or else cloths about the vessel and above if the weather be cold and so let it stand 3 days and 3 nights if the weather be cold. And if it be hot weather 1 day and 1 night is enough at the full. But ever after 1 hour or 2 at the most assay thereof and if you will have it sweet take it he sooner from the dregs as clear as you may into another clean vessel and let it stand 1 night or 2 and then draw it into another clean vessel and serve it forth.And if you will make metheglyn, take sage, hyssop, rosemary, agrimony, saxifrage, betony, centory, lunaria, harts tongue, thyme, maribium album, jon herb, of each a handful if you make 12 gallons and if you make less take the less of herbs and to 4 gallons of the matter 1 gallon of dregs.

I am not the only one who has broken this recipe down, so I will refer to you the following articles, who have done the work for me:

The Mystery of Mead

GreyDragon.org

Open Culture

Notes:

The inclusion of "fine honey" - this is for a good mead! No wax included.

The recipe heats the water before adding the honey, and notes that the yeast should be added to the must as it is still warm - as warm as cow's milk out the tit. Yeast loves warm (but not hot!) environments, so this indicates brewers knew how to handle yeast. The yeast itself comes from "the dregs of finest ale" or barm (frothing, fermenting malt, or another word for yeast) - this brewer is not risking his batch spoiling!

Additionally, the recipe states the mix should be in a warm place, or insulated if too cold - again, indicating that brewers knew that cold weather could kill the yeast, and warm weather would ferment more quickly.

One thing that catches me about all of the recipes I found is the sheer variety in herbs, fruits, and spices. I've compiled a short list of them below:

Cloves

Grain of paradise (akin to a peppercorn, related to ginger)

Ginger

Long pepper (like the peppercorn)

Cubebs (akin to allspice)

Galingale (akin to ginger)

Cinnamon

Corriander

Anise

Heather

Hops

Sage

Rosemary

Plum

Cherries

Hyssop (a relative of mint)

Agrimony (like lemon balm)

Saxifrage (rockfoils)

Betony

Centory (thistle)

Lunaria (mustardy seeds)

Harts tongue

Thyme

Maribum album (horehound, rootbeer and licorice taste)

Jon herb (St. John's Wort, like black tea)

Given the medicinal uses of some of these herbs, and the uses of mild meads as medicines, I wouldn't be surprised if the second recipe here (the metheglin) is used more medicinally than for enjoyment. In any case, I'm excited to experiment with some of these older recipes and see how it turns out!

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inside the house of Lennar: Where will the nation’s biggest homebuilder turn next?

Illustration by Chris Koehler

UPDATED: June 22, 4:43 p.m.: The last decade of Stuart Miller’s 20-year-plus tenure as CEO of Lennar was one for the books. Before announcing his move into the role of executive chairman this past April, the Miami native — and the company — had weathered some significantly stormy weather.

Miller led Lennar through one of the worst housing collapses in U.S. history, fended off an alleged extortion scheme by a convicted fraudster and grew the company’s revenues to over $10.9 billion in 2016.

But by the summer of 2017, Miller knew he needed something else. Something big.

Despite the growing demand for single-family houses, the homebuilding industry was facing a number of pressing challenges. Material and supply costs were rising sharply, and labor shortages were making it difficult for homebuilders to find enough workers to build their homes.

For Miller, the media-shy visionary — and son of the firm’s co-founder — who’s led the now $12 billion public company since 1997, there were no immediate solutions to resolve these massive problems, sources said.

There was one move, however, that could reduce the strain: acquiring another large homebuilder. Through a major acquisition, Lennar could obtain new subcontractors while simultaneously gaining scale, more land and better negotiating power.

“If they are the biggest, it’s like Walmart, everyone wants to work with you, everyone wants to give you a better price,” said Alex Barron, founder of the Housing Research Center.

Unfortunately for Lennar, there were few acquisition options available. Most large homebuilders like Toll Brothers were led by entrepreneurs or families who had no plans of giving up control, while others were too small to alleviate any of Lennar’s challenges.

However, Miller and Lennar’s other executives found one company that didn’t fit this mold: Virginia-based CalAtlantic Group. It was the fourth-largest homebuilder in the U.S. and the product of a rare marriage of equals, Standard Pacific Homes and Ryland Homes, in 2015. A conservative company, Lennar studied CalAtlantic for six months and traveled to all of its home communities before moving forward.

On October 30, 2017, Lennar announced it had finally reached a deal valued at $9.3 billion to acquire CalAtlantic. Though the deal required that Lennar take on CalAtlantic’s $3.6 billion in debt, the acquisition would ultimately make Lennar the largest homebuilder in the country, dethroning D.R. Horton. It was also expected to lower the company’s construction costs by $50 million in 2018.

But in April, a few months after Lennar completed the deal, the company — long known for its stability — made a big announcement.

Miller said he would transition to the role of executive chairman. The move would relinquish the CEO title to someone outside the Miller family for the first time in almost five decades.

Rick Beckwitt, who had served as the company’s president since 2011, took over as CEO.

To analysts and industry onlookers, the selection of Beckwitt didn’t come as much of a surprise. But some doubt that Miller is really handing over complete control of the company to Beckwitt.

“I am sure Stuart is not going anywhere; he is still relatively young,” said Charles Brecker, a partner in Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr’s real estate practice in Miami. “I think that he will still be involved on the macro level.”

Beckwitt, a soft-spoken 30-year industry veteran, will now be in charge of the day-to- day operations. He will take on the seemingly gargantuan task of overseeing the integration of CalAtlantic, which has 573 home communities and 67,622 homesites.

A high-stakes game

The year 2018 will likely be one of the most important in Lennar’s history. While analysts say that none of the company’s moves should be particularly alarming for investors, they come at a difficult time for homebuilders, who are facing macroeconomic headwinds with rising interest rates, escalating construction costs and labor issues that don’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

In addition to those challenges, making one of the largest acquisitions the industry has ever seen means blending the corporate cultures and marketing strategies of two homebuilding behemoths, which is no easy feat.

“They have history going against them,” said Megan McGrath, senior analyst of homebuilding and building products at MKM Partners, an institutional equity research, sales and trading firm. “We don’t see a ton of big [mergers and acquisitions] in this space, and when we have it has not been historically successful.”

McGrath said there have been various reasons why these mega-acquisitions haven’t panned out for homebuilders in the past. One example she cites is Pulte Homes’ $1.3 billion acquisition of Dallas-based Centex Corporation in 2009.

The company’s homebuilding revenue before the acquisition was 60 percent more than what it was postacquisition; in 2010, its revenue was $4.6 billion, down from $6.3 billion in 2008. The company apparently had to write down a bunch of Centex’s assets, causing it to lose money.

Furthermore, when other homebuilders were focused on selling new homes and buying property at distressed prices, Pulte was instead focused on the integration of the acquisition itself rather than on the growth of its existing business, according to McGrath.

“The lesson learned there is you need to be constantly reinvesting your capital,” said McGrath. “So for Lennar, there has to be growth.”

Beckwitt said in a recent conference call with analysts that the integration is going smoothly so far. Out of CalAtlantic’s 573 communities, 100 have already been converted to Lennar products, according to Beckwitt.

But the big challenge, analysts note, is how Lennar will incorporate CalAtlantic’s homes into Lennar’s “Everything’s Included” program.

That slogan and concept originated with Stuart Miller’s father in 1989. The “Everything’s Included” program was designed to give homeowners everything they would need in a home, such as granite countertops, a covered patio and stainless steel refrigerators. For Lennar, it meant homes were built efficiently, allowing the company to maintain profit margins higher than the industry average.

“The ‘Everything’s Included’ philosophy … I don’t think that’s a marketing solution. I think they think it’s the best way to include value,” said McGrath. “They are very, very strict about that building philosophy.”

However, CalAtlantic had a different approach than Lennar, focusing more on the design of the home, with more customization and more upgrade options for luxury homes.

“They [Lennar] look at it more from an investment perspective first, with the emphasis on the aesthetics of the home as secondary,” said Barron, founder of the Housing Research Center.

Strategic alternatives

Lennar’s ascension from a small local homebuilder to an industry giant with more than $12 billion in revenues was due in part to Leonard Miller’s focus on diversifying the company’s revenue stream.

Now this strategy seems poised to change.

Before departing his position, Stuart Miller said in a conference call with analysts that he wanted Lennar to become more of a “pure-play” homebuilder, meaning that Lennar would focus solely on the homebuilding segment of its business.

In October 2017, Lennar sold its Miami headquarters to real estate investment firm Naya USA for $40 million. Lennar retains long-term leases for its office spaces there.

As part of this new strategy, the company has suggested that it is looking to find “strategic alternatives” for its Rialto Group subsidiary, which was formed after the financial crisis to purchase distressed properties. “Strategic alternatives” could mean that Lennar plans to spin off the division, which accounted for $54.3 million out of $2.6 billion in revenues the company logged in its most recent quarterly report.

Analysts said Lennar would be smart to focus on what it does best: building efficient single-family homes at a time when there is a huge shortage and high demand. The National Association of Homebuilders projects that 2018 will have a shortage of almost 400,000 new homes compared to the population growth.

How it all began

One of the most prominent examples of large-scale corporate success in South Florida, Lennar began with Arnold Rosen and Gene Fisher founding F&R Builders in Miami in 1954.

A few years later, a 23-year old Miami businessman named Leonard Miller, who owned 42 lots in what was then Dade County, bought out Fisher’s stake for $10,000.

Miller and Rosen soon began focusing on building low- and moderately priced homes throughout Florida for first-time homebuyers and retirees. The firm went public in 1971 as Lennar Corporation — a combination of Miller and Rosen’s first names — with an $8.7 million IPO.

As CEO, Leonard Miller developed Lennar’s strategy to weather economic downturns by acquiring new businesses and diversifying its revenue streams, while at the same time maintaining a strong balance sheet. In 1977, Lennar expanded outside of Florida by acquiring Mastercraft Homes and Womack Development Company in Phoenix.

Through the next two decades, Lennar started to move into new segments such as home mortgages, forming Universal American Mortgage Company in 1981, giving the company a steady new revenue stream outside of homebuilding.

This also helped Lennar do what analysts say was the key to its success: buying land at depressed prices.

“Their reputation is that they are sharp land buyers,” said Carl Reichardt, an analyst for BTIG, a financial services firm specializing in institutional trading and investment banking.

One of these deals included purchasing the real estate portfolio of AmeriFirst Federal Savings Bank, which failed in 1991, in a partnership with Morgan Stanley & Company. The portfolio consisted of huge tracts of land in South Florida, including 277 undeveloped acres close to the Sawgrass Mills outlet mall in Sunrise.

“When you look at what a homebuilding company is, it’s an asset management company and their asset is land and homes,” said David Cobb, the South Florida regional director at Metrostudy, a provider of market information on the housing industry. “They are aggressive when things look like they are at their worst.”

Keeping it in the family

Stuart Miller had always stayed close to the family business. The son of Leonard and Sue Miller, Stuart mowed the yards of Lennar model homes at age 11, and as he grew older, he performed construction work on Lennar homes.

After graduating from Harvard University and law school at the University of Miami, Miller began working for his father, rising through the ranks to become president of Lennar’s homebuilding subsidiary in 1991.

He became CEO about six years later. Miller quickly established a quirky culture at Lennar. He would open company meetings with the company’s own version of the Dr. Seuss poem “The Little Red Hen”; it was written under the pen name Dr. Stuess, a combination of Stuart and the popular author’s name, according to a Wall Street Journal report.

He instituted a number of company policies designed to make the workplace more egalitarian and friendlier. This included requiring employees to wear name tags and eliminating assigned executive parking spots.

“From what I heard, when they had their sales meeting they would all start off with 20 minutes of cheering,” said Jack McCabe, the CEO of McCabe Research & Consulting. “It’s very different from most homebuilders.”

Stormy weather

Lennar’s culture may have changed under Stuart Miller, but its growth strategy did not. In 2000, the company acquired U.S. Home Corporation for about $1.2 billion, expanding the company’s operations into New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, Minnesota, Ohio and Colorado, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing. By the end of that year, the acquisition gave Lennar housing revenues of almost $5 billion.

But in 2007, an overextension of subprime mortgage lending left the housing industry and the global economy in tatters. Lennar reported losses of over $1.1 billion in net income in 2008, down from gains of $593.8 million in 2006. The company, long regarded a smart cycle timer, however, was able get by, in part by selling off assets at lower prices than they cost.

Then, in January 2009, the firm was forced to confront bogus fraud allegations from a report that compared Lennar to a Bernie Madoff-type Ponzi scheme. The author, Barry Minkow, was found to have published the fake study in a deliberate effort to drive down the company’s stock price. Reports later surfaced that Minkow had been hired by one of Lennar’s former development partners, with whom Miller had had a dispute over cash: San Diego developer Nicolas Marsch. A Florida jury awarded Lennar a $1 billion judgment more than four years later, in December 2013.

21st century and beyond

Historically, Lennar appears to have survived obstacles by constantly adapting and innovating, and it continues to do so in the digital age. The company recently announced that several features in its new homes, such as doorbells and smart locks, will be controlled by Amazon Alexa, a voice-enabled digital assistant. Analysts said that this move was clearly a strategy for recruiting millennial buyers.

“Lennar is well positioned to take advantage of the elephant in the room, which is an age demographic cohort that is just starting to get into their peak years of home ownership,” said Ralph McLaughlin, chief economist and founder of Veritas Urbis Economics. “Over the next 10 to 15 years, this demographic is going to be buying homes, and if you are providing them, you are going to do very well.”

Correction: This story has been updated to state that Stuart Miller is not retiring. He will remain active in his new role as executive chairman of Lennar.

from The Real Deal Miami https://therealdeal.com/miami/issues_articles/inside-the-house-of-lennar/#new_tab via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Inside the house of Lennar: Where will the nation’s biggest homebuilder turn next?

Illustration by Chris Koehler

UPDATED: June 22, 4:43 p.m.: The last decade of Stuart Miller’s 20-year-plus tenure as CEO of Lennar was one for the books. Before announcing his move into the role of executive chairman this past April, the Miami native — and the company — had weathered some significantly stormy weather.

Miller led Lennar through one of the worst housing collapses in U.S. history, fended off an alleged extortion scheme by a convicted fraudster and grew the company’s revenues to over $10.9 billion in 2016.

But by the summer of 2017, Miller knew he needed something else. Something big.

Despite the growing demand for single-family houses, the homebuilding industry was facing a number of pressing challenges. Material and supply costs were rising sharply, and labor shortages were making it difficult for homebuilders to find enough workers to build their homes.

For Miller, the media-shy visionary — and son of the firm’s co-founder — who’s led the now $12 billion public company since 1997, there were no immediate solutions to resolve these massive problems, sources said.

There was one move, however, that could reduce the strain: acquiring another large homebuilder. Through a major acquisition, Lennar could obtain new subcontractors while simultaneously gaining scale, more land and better negotiating power.

“If they are the biggest, it’s like Walmart, everyone wants to work with you, everyone wants to give you a better price,” said Alex Barron, founder of the Housing Research Center.

Unfortunately for Lennar, there were few acquisition options available. Most large homebuilders like Toll Brothers were led by entrepreneurs or families who had no plans of giving up control, while others were too small to alleviate any of Lennar’s challenges.

However, Miller and Lennar’s other executives found one company that didn’t fit this mold: Virginia-based CalAtlantic Group. It was the fourth-largest homebuilder in the U.S. and the product of a rare marriage of equals, Standard Pacific Homes and Ryland Homes, in 2015. A conservative company, Lennar studied CalAtlantic for six months and traveled to all of its home communities before moving forward.

On October 30, 2017, Lennar announced it had finally reached a deal valued at $9.3 billion to acquire CalAtlantic. Though the deal required that Lennar take on CalAtlantic’s $3.6 billion in debt, the acquisition would ultimately make Lennar the largest homebuilder in the country, dethroning D.R. Horton. It was also expected to lower the company’s construction costs by $50 million in 2018.

But in April, a few months after Lennar completed the deal, the company — long known for its stability — made a big announcement.

Miller said he would transition to the role of executive chairman. The move would relinquish the CEO title to someone outside the Miller family for the first time in almost five decades.

Rick Beckwitt, who had served as the company’s president since 2011, took over as CEO.

To analysts and industry onlookers, the selection of Beckwitt didn’t come as much of a surprise. But some doubt that Miller is really handing over complete control of the company to Beckwitt.

“I am sure Stuart is not going anywhere; he is still relatively young,” said Charles Brecker, a partner in Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr’s real estate practice in Miami. “I think that he will still be involved on the macro level.”

Beckwitt, a soft-spoken 30-year industry veteran, will now be in charge of the day-to- day operations. He will take on the seemingly gargantuan task of overseeing the integration of CalAtlantic, which has 573 home communities and 67,622 homesites.

A high-stakes game

The year 2018 will likely be one of the most important in Lennar’s history. While analysts say that none of the company’s moves should be particularly alarming for investors, they come at a difficult time for homebuilders, who are facing macroeconomic headwinds with rising interest rates, escalating construction costs and labor issues that don’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

In addition to those challenges, making one of the largest acquisitions the industry has ever seen means blending the corporate cultures and marketing strategies of two homebuilding behemoths, which is no easy feat.

“They have history going against them,” said Megan McGrath, senior analyst of homebuilding and building products at MKM Partners, an institutional equity research, sales and trading firm. “We don’t see a ton of big [mergers and acquisitions] in this space, and when we have it has not been historically successful.”

McGrath said there have been various reasons why these mega-acquisitions haven’t panned out for homebuilders in the past. One example she cites is Pulte Homes’ $1.3 billion acquisition of Dallas-based Centex Corporation in 2009.

The company’s homebuilding revenue before the acquisition was 60 percent more than what it was postacquisition; in 2010, its revenue was $4.6 billion, down from $6.3 billion in 2008. The company apparently had to write down a bunch of Centex’s assets, causing it to lose money.

Furthermore, when other homebuilders were focused on selling new homes and buying property at distressed prices, Pulte was instead focused on the integration of the acquisition itself rather than on the growth of its existing business, according to McGrath.

“The lesson learned there is you need to be constantly reinvesting your capital,” said McGrath. “So for Lennar, there has to be growth.”

Beckwitt said in a recent conference call with analysts that the integration is going smoothly so far. Out of CalAtlantic’s 573 communities, 100 have already been converted to Lennar products, according to Beckwitt.

But the big challenge, analysts note, is how Lennar will incorporate CalAtlantic’s homes into Lennar’s “Everything’s Included” program.

That slogan and concept originated with Stuart Miller’s father in 1989. The “Everything’s Included” program was designed to give homeowners everything they would need in a home, such as granite countertops, a covered patio and stainless steel refrigerators. For Lennar, it meant homes were built efficiently, allowing the company to maintain profit margins higher than the industry average.

“The ‘Everything’s Included’ philosophy … I don’t think that’s a marketing solution. I think they think it’s the best way to include value,” said McGrath. “They are very, very strict about that building philosophy.”

However, CalAtlantic had a different approach than Lennar, focusing more on the design of the home, with more customization and more upgrade options for luxury homes.

“They [Lennar] look at it more from an investment perspective first, with the emphasis on the aesthetics of the home as secondary,” said Barron, founder of the Housing Research Center.

Strategic alternatives

Lennar’s ascension from a small local homebuilder to an industry giant with more than $12 billion in revenues was due in part to Leonard Miller’s focus on diversifying the company’s revenue stream.

Now this strategy seems poised to change.

Before departing his position, Stuart Miller said in a conference call with analysts that he wanted Lennar to become more of a “pure-play” homebuilder, meaning that Lennar would focus solely on the homebuilding segment of its business.

In October 2017, Lennar sold its Miami headquarters to real estate investment firm Naya USA for $40 million. Lennar retains long-term leases for its office spaces there.

As part of this new strategy, the company has suggested that it is looking to find “strategic alternatives” for its Rialto Group subsidiary, which was formed after the financial crisis to purchase distressed properties. “Strategic alternatives” could mean that Lennar plans to spin off the division, which accounted for $54.3 million out of $2.6 billion in revenues the company logged in its most recent quarterly report.

Analysts said Lennar would be smart to focus on what it does best: building efficient single-family homes at a time when there is a huge shortage and high demand. The National Association of Homebuilders projects that 2018 will have a shortage of almost 400,000 new homes compared to the population growth.

How it all began

One of the most prominent examples of large-scale corporate success in South Florida, Lennar began with Arnold Rosen and Gene Fisher founding F&R Builders in Miami in 1954.

A few years later, a 23-year old Miami businessman named Leonard Miller, who owned 42 lots in what was then Dade County, bought out Fisher’s stake for $10,000.

Miller and Rosen soon began focusing on building low- and moderately priced homes throughout Florida for first-time homebuyers and retirees. The firm went public in 1971 as Lennar Corporation — a combination of Miller and Rosen’s first names — with an $8.7 million IPO.

As CEO, Leonard Miller developed Lennar’s strategy to weather economic downturns by acquiring new businesses and diversifying its revenue streams, while at the same time maintaining a strong balance sheet. In 1977, Lennar expanded outside of Florida by acquiring Mastercraft Homes and Womack Development Company in Phoenix.

Through the next two decades, Lennar started to move into new segments such as home mortgages, forming Universal American Mortgage Company in 1981, giving the company a steady new revenue stream outside of homebuilding.

This also helped Lennar do what analysts say was the key to its success: buying land at depressed prices.

“Their reputation is that they are sharp land buyers,” said Carl Reichardt, an analyst for BTIG, a financial services firm specializing in institutional trading and investment banking.

One of these deals included purchasing the real estate portfolio of AmeriFirst Federal Savings Bank, which failed in 1991, in a partnership with Morgan Stanley & Company. The portfolio consisted of huge tracts of land in South Florida, including 277 undeveloped acres close to the Sawgrass Mills outlet mall in Sunrise.

“When you look at what a homebuilding company is, it’s an asset management company and their asset is land and homes,” said David Cobb, the South Florida regional director at Metrostudy, a provider of market information on the housing industry. “They are aggressive when things look like they are at their worst.”

Keeping it in the family

Stuart Miller had always stayed close to the family business. The son of Leonard and Sue Miller, Stuart mowed the yards of Lennar model homes at age 11, and as he grew older, he performed construction work on Lennar homes.

After graduating from Harvard University and law school at the University of Miami, Miller began working for his father, rising through the ranks to become president of Lennar’s homebuilding subsidiary in 1991.

He became CEO about six years later. Miller quickly established a quirky culture at Lennar. He would open company meetings with the company’s own version of the Dr. Seuss poem “The Little Red Hen”; it was written under the pen name Dr. Stuess, a combination of Stuart and the popular author’s name, according to a Wall Street Journal report.

He instituted a number of company policies designed to make the workplace more egalitarian and friendlier. This included requiring employees to wear name tags and eliminating assigned executive parking spots.

“From what I heard, when they had their sales meeting they would all start off with 20 minutes of cheering,” said Jack McCabe, the CEO of McCabe Research & Consulting. “It’s very different from most homebuilders.”

Stormy weather

Lennar’s culture may have changed under Stuart Miller, but its growth strategy did not. In 2000, the company acquired U.S. Home Corporation for about $1.2 billion, expanding the company’s operations into New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, Minnesota, Ohio and Colorado, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing. By the end of that year, the acquisition gave Lennar housing revenues of almost $5 billion.

But in 2007, an overextension of subprime mortgage lending left the housing industry and the global economy in tatters. Lennar reported losses of over $1.1 billion in net income in 2008, down from gains of $593.8 million in 2006. The company, long regarded a smart cycle timer, however, was able get by, in part by selling off assets at lower prices than they cost.

Then, in January 2009, the firm was forced to confront bogus fraud allegations from a report that compared Lennar to a Bernie Madoff-type Ponzi scheme. The author, Barry Minkow, was found to have published the fake study in a deliberate effort to drive down the company’s stock price. Reports later surfaced that Minkow had been hired by one of Lennar’s former development partners, with whom Miller had had a dispute over cash: San Diego developer Nicolas Marsch. A Florida jury awarded Lennar a $1 billion judgment more than four years later, in December 2013.

21st century and beyond

Historically, Lennar appears to have survived obstacles by constantly adapting and innovating, and it continues to do so in the digital age. The company recently announced that several features in its new homes, such as doorbells and smart locks, will be controlled by Amazon Alexa, a voice-enabled digital assistant. Analysts said that this move was clearly a strategy for recruiting millennial buyers.

“Lennar is well positioned to take advantage of the elephant in the room, which is an age demographic cohort that is just starting to get into their peak years of home ownership,” said Ralph McLaughlin, chief economist and founder of Veritas Urbis Economics. “Over the next 10 to 15 years, this demographic is going to be buying homes, and if you are providing them, you are going to do very well.”

Correction: This story has been updated to state that Stuart Miller is not retiring. He will remain active in his new role as executive chairman of Lennar.

from The Real Deal Miami https://therealdeal.com/miami/issues_articles/inside-the-house-of-lennar/#new_tab via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Inside the house of Lennar: Where will the nation’s biggest homebuilder turn next?

Illustration by Chris Koehler

UPDATED: June 22, 4:43 p.m.: The last decade of Stuart Miller’s 20-year-plus tenure as CEO of Lennar was one for the books. Before announcing his move into the role of executive chairman this past April, the Miami native — and the company — had weathered some significantly stormy weather.

Miller led Lennar through one of the worst housing collapses in U.S. history, fended off an alleged extortion scheme by a convicted fraudster and grew the company’s revenues to over $10.9 billion in 2016.

But by the summer of 2017, Miller knew he needed something else. Something big.

Despite the growing demand for single-family houses, the homebuilding industry was facing a number of pressing challenges. Material and supply costs were rising sharply, and labor shortages were making it difficult for homebuilders to find enough workers to build their homes.

For Miller, the media-shy visionary — and son of the firm’s co-founder — who’s led the now $12 billion public company since 1997, there were no immediate solutions to resolve these massive problems, sources said.

There was one move, however, that could reduce the strain: acquiring another large homebuilder. Through a major acquisition, Lennar could obtain new subcontractors while simultaneously gaining scale, more land and better negotiating power.

“If they are the biggest, it’s like Walmart, everyone wants to work with you, everyone wants to give you a better price,” said Alex Barron, founder of the Housing Research Center.

Unfortunately for Lennar, there were few acquisition options available. Most large homebuilders like Toll Brothers were led by entrepreneurs or families who had no plans of giving up control, while others were too small to alleviate any of Lennar’s challenges.

However, Miller and Lennar’s other executives found one company that didn’t fit this mold: Virginia-based CalAtlantic Group. It was the fourth-largest homebuilder in the U.S. and the product of a rare marriage of equals, Standard Pacific Homes and Ryland Homes, in 2015. A conservative company, Lennar studied CalAtlantic for six months and traveled to all of its home communities before moving forward.

On October 30, 2017, Lennar announced it had finally reached a deal valued at $9.3 billion to acquire CalAtlantic. Though the deal required that Lennar take on CalAtlantic’s $3.6 billion in debt, the acquisition would ultimately make Lennar the largest homebuilder in the country, dethroning D.R. Horton. It was also expected to lower the company’s construction costs by $50 million in 2018.

But in April, a few months after Lennar completed the deal, the company — long known for its stability — made a big announcement.

Miller said he would transition to the role of executive chairman. The move would relinquish the CEO title to someone outside the Miller family for the first time in almost five decades.

Rick Beckwitt, who had served as the company’s president since 2011, took over as CEO.

To analysts and industry onlookers, the selection of Beckwitt didn’t come as much of a surprise. But some doubt that Miller is really handing over complete control of the company to Beckwitt.

“I am sure Stuart is not going anywhere; he is still relatively young,” said Charles Brecker, a partner in Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr’s real estate practice in Miami. “I think that he will still be involved on the macro level.”

Beckwitt, a soft-spoken 30-year industry veteran, will now be in charge of the day-to- day operations. He will take on the seemingly gargantuan task of overseeing the integration of CalAtlantic, which has 573 home communities and 67,622 homesites.

A high-stakes game

The year 2018 will likely be one of the most important in Lennar’s history. While analysts say that none of the company’s moves should be particularly alarming for investors, they come at a difficult time for homebuilders, who are facing macroeconomic headwinds with rising interest rates, escalating construction costs and labor issues that don’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

In addition to those challenges, making one of the largest acquisitions the industry has ever seen means blending the corporate cultures and marketing strategies of two homebuilding behemoths, which is no easy feat.

“They have history going against them,” said Megan McGrath, senior analyst of homebuilding and building products at MKM Partners, an institutional equity research, sales and trading firm. “We don’t see a ton of big [mergers and acquisitions] in this space, and when we have it has not been historically successful.”

McGrath said there have been various reasons why these mega-acquisitions haven’t panned out for homebuilders in the past. One example she cites is Pulte Homes’ $1.3 billion acquisition of Dallas-based Centex Corporation in 2009.

The company’s homebuilding revenue before the acquisition was 60 percent more than what it was postacquisition; in 2010, its revenue was $4.6 billion, down from $6.3 billion in 2008. The company apparently had to write down a bunch of Centex’s assets, causing it to lose money.

Furthermore, when other homebuilders were focused on selling new homes and buying property at distressed prices, Pulte was instead focused on the integration of the acquisition itself rather than on the growth of its existing business, according to McGrath.

“The lesson learned there is you need to be constantly reinvesting your capital,” said McGrath. “So for Lennar, there has to be growth.”

Beckwitt said in a recent conference call with analysts that the integration is going smoothly so far. Out of CalAtlantic’s 573 communities, 100 have already been converted to Lennar products, according to Beckwitt.

But the big challenge, analysts note, is how Lennar will incorporate CalAtlantic’s homes into Lennar’s “Everything’s Included” program.

That slogan and concept originated with Stuart Miller’s father in 1989. The “Everything’s Included” program was designed to give homeowners everything they would need in a home, such as granite countertops, a covered patio and stainless steel refrigerators. For Lennar, it meant homes were built efficiently, allowing the company to maintain profit margins higher than the industry average.

“The ‘Everything’s Included’ philosophy … I don’t think that’s a marketing solution. I think they think it’s the best way to include value,” said McGrath. “They are very, very strict about that building philosophy.”

However, CalAtlantic had a different approach than Lennar, focusing more on the design of the home, with more customization and more upgrade options for luxury homes.

“They [Lennar] look at it more from an investment perspective first, with the emphasis on the aesthetics of the home as secondary,” said Barron, founder of the Housing Research Center.

Strategic alternatives

Lennar’s ascension from a small local homebuilder to an industry giant with more than $12 billion in revenues was due in part to Leonard Miller’s focus on diversifying the company’s revenue stream.

Now this strategy seems poised to change.

Before departing his position, Stuart Miller said in a conference call with analysts that he wanted Lennar to become more of a “pure-play” homebuilder, meaning that Lennar would focus solely on the homebuilding segment of its business.

In October 2017, Lennar sold its Miami headquarters to real estate investment firm Naya USA for $40 million. Lennar retains long-term leases for its office spaces there.

As part of this new strategy, the company has suggested that it is looking to find “strategic alternatives” for its Rialto Group subsidiary, which was formed after the financial crisis to purchase distressed properties. “Strategic alternatives” could mean that Lennar plans to spin off the division, which accounted for $54.3 million out of $2.6 billion in revenues the company logged in its most recent quarterly report.

Analysts said Lennar would be smart to focus on what it does best: building efficient single-family homes at a time when there is a huge shortage and high demand. The National Association of Homebuilders projects that 2018 will have a shortage of almost 400,000 new homes compared to the population growth.

How it all began

One of the most prominent examples of large-scale corporate success in South Florida, Lennar began with Arnold Rosen and Gene Fisher founding F&R Builders in Miami in 1954.

A few years later, a 23-year old Miami businessman named Leonard Miller, who owned 42 lots in what was then Dade County, bought out Fisher’s stake for $10,000.

Miller and Rosen soon began focusing on building low- and moderately priced homes throughout Florida for first-time homebuyers and retirees. The firm went public in 1971 as Lennar Corporation — a combination of Miller and Rosen’s first names — with an $8.7 million IPO.

As CEO, Leonard Miller developed Lennar’s strategy to weather economic downturns by acquiring new businesses and diversifying its revenue streams, while at the same time maintaining a strong balance sheet. In 1977, Lennar expanded outside of Florida by acquiring Mastercraft Homes and Womack Development Company in Phoenix.

Through the next two decades, Lennar started to move into new segments such as home mortgages, forming Universal American Mortgage Company in 1981, giving the company a steady new revenue stream outside of homebuilding.

This also helped Lennar do what analysts say was the key to its success: buying land at depressed prices.

“Their reputation is that they are sharp land buyers,” said Carl Reichardt, an analyst for BTIG, a financial services firm specializing in institutional trading and investment banking.

One of these deals included purchasing the real estate portfolio of AmeriFirst Federal Savings Bank, which failed in 1991, in a partnership with Morgan Stanley & Company. The portfolio consisted of huge tracts of land in South Florida, including 277 undeveloped acres close to the Sawgrass Mills outlet mall in Sunrise.

“When you look at what a homebuilding company is, it’s an asset management company and their asset is land and homes,” said David Cobb, the South Florida regional director at Metrostudy, a provider of market information on the housing industry. “They are aggressive when things look like they are at their worst.”

Keeping it in the family

Stuart Miller had always stayed close to the family business. The son of Leonard and Sue Miller, Stuart mowed the yards of Lennar model homes at age 11, and as he grew older, he performed construction work on Lennar homes.

After graduating from Harvard University and law school at the University of Miami, Miller began working for his father, rising through the ranks to become president of Lennar’s homebuilding subsidiary in 1991.

He became CEO about six years later. Miller quickly established a quirky culture at Lennar. He would open company meetings with the company’s own version of the Dr. Seuss poem “The Little Red Hen”; it was written under the pen name Dr. Stuess, a combination of Stuart and the popular author’s name, according to a Wall Street Journal report.

He instituted a number of company policies designed to make the workplace more egalitarian and friendlier. This included requiring employees to wear name tags and eliminating assigned executive parking spots.

“From what I heard, when they had their sales meeting they would all start off with 20 minutes of cheering,” said Jack McCabe, the CEO of McCabe Research & Consulting. “It’s very different from most homebuilders.”

Stormy weather

Lennar’s culture may have changed under Stuart Miller, but its growth strategy did not. In 2000, the company acquired U.S. Home Corporation for about $1.2 billion, expanding the company’s operations into New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, Minnesota, Ohio and Colorado, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing. By the end of that year, the acquisition gave Lennar housing revenues of almost $5 billion.

But in 2007, an overextension of subprime mortgage lending left the housing industry and the global economy in tatters. Lennar reported losses of over $1.1 billion in net income in 2008, down from gains of $593.8 million in 2006. The company, long regarded a smart cycle timer, however, was able get by, in part by selling off assets at lower prices than they cost.

Then, in January 2009, the firm was forced to confront bogus fraud allegations from a report that compared Lennar to a Bernie Madoff-type Ponzi scheme. The author, Barry Minkow, was found to have published the fake study in a deliberate effort to drive down the company’s stock price. Reports later surfaced that Minkow had been hired by one of Lennar’s former development partners, with whom Miller had had a dispute over cash: San Diego developer Nicolas Marsch. A Florida jury awarded Lennar a $1 billion judgment more than four years later, in December 2013.

21st century and beyond

Historically, Lennar appears to have survived obstacles by constantly adapting and innovating, and it continues to do so in the digital age. The company recently announced that several features in its new homes, such as doorbells and smart locks, will be controlled by Amazon Alexa, a voice-enabled digital assistant. Analysts said that this move was clearly a strategy for recruiting millennial buyers.

“Lennar is well positioned to take advantage of the elephant in the room, which is an age demographic cohort that is just starting to get into their peak years of home ownership,” said Ralph McLaughlin, chief economist and founder of Veritas Urbis Economics. “Over the next 10 to 15 years, this demographic is going to be buying homes, and if you are providing them, you are going to do very well.”

Correction: This story has been updated to state that Stuart Miller is not retiring. He will remain active in his new role as executive chairman of Lennar.

from The Real Deal Miami https://therealdeal.com/miami/issues_articles/inside-the-house-of-lennar/#new_tab via IFTTT

0 notes