#Reiko Tomii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

AR: Yutaka Matsuzawa at Yale Union

#Alan Longino#August Review#Portland#Reiko Tomii#Uncategorized#United States#Yale Union#Yutaka Matsuzawa

91 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Horikawa Michio

- The Shinano River Plan: 11

1969

From the series “Mail Art By Sending Stones”

Collection of Matsuzawa Kumiko.

Photo by Reiko Tomii

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

Installation view of Vanishing in the Wilderness, Yutaka Matsuzawa, Empty Gallery. Courtesy of Matsuzawa Kumiko and Empty Gallery. Photo: Michael Yu

En fait, je n'écris pas pour les morts, mais pour les vivants, mais bien sûr pour ceux qui savent que les morts aussi existent. Paul Celan, Les microlithes, ce sont des petits cailloux , 1969

Empty Gallery a le plaisir de présenter Yutaka Matsuzawa : Disparition dans le désert. Co-organisée par Alan Longino et Reiko Tomii, et réalisée avec l'aide généreuse de la famille Matsuzawa, cette exposition représente le premier aperçu de la pratique de cet artiste pivot en Asie de l'Est sinophone. Largement considéré comme le principal pionnier de l'art conceptuel japonais, la pratique de Matsuzawa a synthétisé un large éventail de connaissances orientales et occidentales - y compris la parapsychologie, le bouddhisme de la Terre pure et la physique quantique - dans la poursuite de stratégies artistiques pour exprimer la sphère immatérielle.

artviewer.org

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

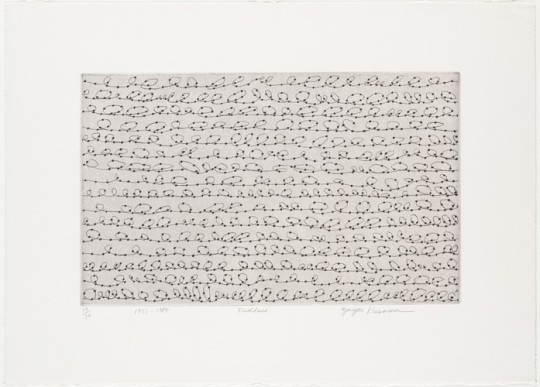

Endless, Yayoi Kusama, 1953–84, MoMA: Drawings and Prints

Gift of Jeff Rothstein and Reiko Tomii in memory of Bhupendra Karia Size: composition: 10 11/16 x 17 9/16" (27.1 x 44.6 cm); sheet: 17 11/16 x 24 3/4" (45 x 62.8 cm) Medium: Etching

http://www.moma.org/collection/works/60977

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Postwar Conference: GROUND ZERO, Panel 2 / 22.05.14

0 notes

Photo

To celebrate the Chinese New Year, we're getting some inspiration from 'Cai Guo-Qiang: Odyssey and Homecoming' — an epic exploration of the artist internationally renowned for his unique gunpowder art — published by @delmonico_books Edited with text by Simon Schama. Text by Cai Guo-Qiang, Yu Hui, Wang Hui, Rachel Rivenc, Reiko Tomii, Sang Luo. Read more via linkinbio @caistudio #caiguoqiang #simonschama #odysseyandhomecoming https://www.instagram.com/p/CZc0S2pJFsM/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

Radicalism in the Wilderness

BOOK REVIEW

[expanded version of review published in Japan Times on 26/02/17]

Reiko Tomii (2016) Radicalism in the Wildnerness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan. Boston, MA: MIT Press, pp. xviii+293

Reiko Tomii’s profound, yet accessible, study of 1960s avant garde art from Japan offers an answer to a perennial problem in the appreciation of Japanese culture. So often international observers rely on the perception that culture from Japan is “exquisite” or “cool”, without knowing how or where to place it in international currents. Japan indeed often represents a clichéd parade of the exotic, weird and plain off-the-wall. At the same time, avant garde movements, seen to be delayed copies of trends which started in London, Paris or New York, have often been ridiculed as derivative—as infamously happended to the pioneering Gutai group of artists, when their works were first compared alongside Jackson Pollack in 1958. The apparent craziness of Japanese avant garde gestures also frequently baffles, its throaway ephemerality and “vanguard extremism” foregrounded for amusement: all those 1960s artists with a predilection for dangerous group stunts, often in the nude... The well known critic Yoshiaki Tōno once said in frustration that this was like forever equating its avant garde artists to wartime kamikaze pilots.

.

Reiko Tomii’s mission is to retrieve these misunderstood visionaries from the “abyss of history”. For many years, she has been the leading figure of a New York-centred network of art historians (PoNJA GenKon) working to establish the reputation of avant garde fine art from Japan in the post-war period. As an independent writer, educator and curator, she has been involved in many of the key translations of contemporary Japanese art writing, and some of the most important exhibitions in the city. In her own work and those around her, she has marshalled the flowering of understanding about Japanese art from the 1950s and 60s in particular. Radicalism in the Wildeness reads like a lifework, many years in the gestation. And, although it may seem to be on a specialised topic, its argument holds a very broad significance for the global study of culture.

.

Tomii cuts to the heart of the dilemma of how we are to understand what she calls the “contemporaneity” (kokusaiteki dōjisei) of Japanese works: striking and original art that was similar yet dissimilar to more renowned innovations taking place at around the same time in the US or Europe. They were neither really in advance nor behind, but with careful reconstruction of their relations, can all be placed correctly as part of global innovation, through a comparative and transnational exposure of what she calls “connections” and “resonances”. Sometimes real networks and direct translation of ideas can be found; and sometimes, rather, related discoveries of global import were being made synchronously in local places, in different parts of the world. The history she writes is of the 1960s, when events in culture and politics were momentous everywhere, with a heightened globility intensified by growing linkages. She is proposing, in effect, a model for the study of global transactions and undercurrents, which can work to decentre the Eurocentric tendencies of conventional art history, while underlining a historical lesson of understanding the global as happening at once and variously in multiple, distinct locations. At the same time, the Japanese embraced a conception of “contemporary art” (gendai bijutsu) in the 1960s, that was ahead of the notion “contemporary” being adopted in the US and Europe.

.

The book is built around three particular case studies of artists, among the lesser known in the pantheon of post-war Japanese art. These vivid presentations are a masterclass of art historical writing in their precise documentation and narrative unfolding. The first, Yutaka Matsuzawa, was a philosophically minded conceptualist whose purpose as an artist became clear when he had a vision about art needing to “vanish the object”. After the suspension of the famous Tokyo avant garde art show, the Yomiuri Independent Exhibition, in 1964, he went on to to staging exhibitions of invisible art works in remote locations. Next up, The Play, were a 60s collective in the Kansai region who coalesced as a group to devise a mode of working outside art instutions with absurdist performances. In a famous piece they all rode together on a styrofoam raft shaped like an arrow down river from Kyoto to Osaka. The third, GUN (Group Ultra Niigata) experimented with a Japanese variant of land art. The cover of the book shows their work in a mountainous part of Niigata, spraying colour in a snow field out of borrowed farmer’s pesticide equipment. Each of these artists and groups took their radical reaction to the constraints of mainstream society and culture out into the wildnerness of rural Japan.

.

This idea of “wilderness” as a key characteristic of Japanese contemporary art plays a central role in Tomii’s argumentation. It refers to those who have often worked in rural locations outside of institutionalised forms and channels of recognition, far from metropolitanTokyo. It also speaks of the wilderness of working in the absense of any viable commercial form of making a living—it is this which leads to the ephemerality and physicality of contemporary art gestures, in what Tomii calls the chronically under-commodified environment of Japan, compared to highly self-conscious performances of Euro-American conceptualism when it took a break from lucrative gallery shows. It is also the wilderness of Japan in relation to the world’s art centres and powers.

.

How much these artists fulfill the promise of “radicalism” in the title is sometimes harder to grasp. Unlike, say, the much celebrated Genpai Akasegawa who fell into long running conflicts with the authoriries for his work, such as his model Y1,000 note, these artists were rarely political in a direct sense. The leader of Gun, Michio Horikawa, posted a black stone to Richard Nixon in 1969 (which was politiely received), and printed fake zero en postage stamps with the prime minister’s face. But on the whole, these artists shunned the political activism of the time, and steered well clear of any grounded social engagement of the kind nowadays so widespread in Japan. Tomii sees this as a strong point: that their interventions, as art, now restored to the canon, have lasted so much longer than the futile violence of 60s and 70s radical leftists. At the same time, their absurdist gestures were accused of being “bourgeois art”.

.

Tomii’s writing works as handbook of contemporary art history references, but more connections might be made with the long standing post-colonial literatures in historiography, philosophy and sociology, which have long wrestled with issues of “provincialising” the West, or revealing the power of “glocal” cultural forms. Tomii, in effect, proposes an addition to these “decolonial” models and it would be good to see her work rightly placed at the heart of intense current debates on the idea of thus studying “Asia as Method”.

.

For all their iconoclastic edge, the 1960s pioneers were absorbed into Japanese museum presentations in the 1970s, and they have received some wider appreciation in recent years. Matsuzawa’s famous Psi Zashiki Room was recreated for visitors at the Yokohama Triennale 2014 by artist-curator Yasumasa Morimura. The Play have recreated their work in Paris, and attracted the attention of international curators such as Tom Trevor. GUN’s rural work, which remains a little more obscure, was a precuror to the Echigo-Tsumari art triennale, which takes place in the same region. Tomii’s rigorous “amplification” of these figures puts them back into a “decentred” canon, “regrouping” post-war Japanese art as among the most extraordinary production world wide.

.

Over-emphasising this art historical point, though, would be to limit this book to specialists. Beautifully written and structured, Radicalism in the Wilderness is a book for any culturally literate reader interested in questioning how to study regional art in its correct international context. As it is discovered, it will surely receive wide attention: as a central contribution to post-colonial work re-assessing ideas of centre and periphery, and a very-likely-to-be classic contribution to global cultural studies.

.

Adrian Favell

http://www.adrianfavell.com

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Artist: Yutaka Matsuzawa

Venue: Yale Union, Portland

Curated By: Alan Longino, Reiko Tomii

Date: June 30 – August 18, 2019

Note: A text associated with the exhibition written by Alan Longino can be downloaded here.

Click here to view slideshow

Originally Posted: August 9th, 2019

Note: This entry is part of August Review, our annual look back at this season’s key exhibitions. For more information, see the announcement here.

from Contemporary Art Daily https://bit.ly/3khsmUD

0 notes

Photo

Yutaka Matsuzawa at Yale Union

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japan, in from the Wilderness: Reiko Tomii’s Expanded Modern-Art History

via Hyperallergic

Edward M. Gómez

The Japanese-born art historian Reiko Tomii is one of those researchers who is both passionate about her subjects and recognized among her peers for her meticulous mapping of the cultural-intellectual terrain from which they emerge. An independent scholar who has lived and worked in the United States since the mid-1980s and has been based in New York for many years, Tomii has focused on the artists and art movements of post-World War II Japan, carefully classifying their evolution and ideas, as well as their constituent parts, antecedents and relevant affinities.

Although she admits that “art history is not a precise science,” her own approach is unmistakably fine-tuned, and she is an inventive thinker. The results and revelations of her method are well showcased in her new book, Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (MIT Press).

“Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan” by Reiko Tomii (courtesy MIT Press) (click to enlarge)

In it, she takes on modern-art history’s familiar, canonical narrative, which, understandably, has long focused on the ideas, artists, movements, and milestone events that are linked to its roots territories in Europe and North America. However, Tomii does not take a crowbar to this history with the intent of forcing open its pantheon of recognized masters to make room for less well-known but attention-deserving modernists from Japan.

Instead, her objective reflects the interests of a still-evolving but ever more notable tendency among certain researchers and curators in the U.S., Europe and East Asia to examine modern art’s development with a broader, deeper, more inclusive scope.

Their new consideration of modern art’s story has brought such places as Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Delhi and Prague into sharper focus. (In the US, Alexandra Munroe, the senior curator of Asian art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York has been a trailblazer in this effort since the mid-1990s. More recently, such museums as Tate Modern in London, the Stedelijk in Amsterdam and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have appointed new curators or developed special research programs to pursue this new outlook.)

Tomii’s own research and curatorial work have contributed significantly to this new, so-called global view of modern art’s history. In Radicalism in the Wilderness, she describes “international contemporaneity” as “a geohistorical concept, one that liberates us from the inevitable obsession with the present inherent in ‘contemporaneity’ as used in the English construction of ‘contemporary art’ (whose basic meaning is ‘art of present times’) and helps us devise an expansive historical framework” by means of which “a multicentered world art history” may be told. She argues that an understanding of this phenomenon may make room for overlooked or ignored currents in the story of modern art as it developed in 20th-century Japan after World War II. She also puts forth the related notions of what she calls “connections” and “resonances,” the meanings of which become self-evident as her study unfolds.

However, looking back at past events and examining the “international contemporaneity” of a certain moment or era from a particular vantage point is not quite the same as taking the pulse of its Zeitgeist. Instead, keen observers like Tomii are on the lookout for similar expressions, ideas, or breakthroughs that occur in different places at more or less the same time. In this way, Tomii notes, historians aiming to construct a global history of modern art must “seek out and examine linkable ‘contact points’ of geohistory,” where they will find evidence of what she calls “connections,” or “actual interactions and other kinds of links” between artists, critics, curators and other figures in the world of art, and “resonances,” which she defines as “visual or conceptual similarities” between artists’ ideas, creations or activities, even in situations in which “few or faint links existed.”

Tomii uses the examples of one solo artist and two artists’ collectives that were active in Japan in the 1960s, and whose works can be classified as conceptual art, to illustrate her observations about “international contemporaneity.” These artists’ careers offer intentional and unwitting points of contact with artists in the US and Europe. Tomii cites Yutaka Matsuzawa, who was born in 1922 in central Japan, earned a degree in architecture in Tokyo, and returned to his native region, where he later came up with art forms that reflected his disenchantment with “material civilization.”

He spent a couple of years in the US, including a stay in New York in the late 1950s, looking at art— Jackson Pollock’s paintings, Robert Rauschenberg’s mixed-media “combines” — and learning about parapsychology. Matsuzawa was interested in physics, Buddhist thought and the idea of visualizing the invisible. Back in Japan, he developed works that invited viewer-participants to “vanish” certain subjects — to make them disappear. (He once told an audience at his university, “I don’t believe in the solidness of iron and concrete. I want to create an architecture of soul, a formless architecture, an invisible architecture.”) At the exhibition Tokyo Biennale 1970: Between Man and Matter, in which both Japanese and numerous, well-known Western artists took part — a milestone, Tomii notes in retrospect, of “international contemporaneity” — Matsuzawa offered an empty room titled “My Own Death.”

Tomii also looks at the activities of The Play, a group of “Happeners,” founded in Osaka in 1967, who devised and carried out their own versions of “Happenings,” those action-as-art events that blasted the idea of the work of art as a physical object. The Play’s message, Tomii writes, “was constructive, not destructive, as their major concern was to take a ‘voyage’ away from everyday consciousness trapped in familiar space and time.” Their provocative events included erecting a huge cross made of white fabric atop a mountain (for which they intended no specific message, although it called attention to nearby urban zones’ proximity to nature), and group member Keiichi Ikemizu’s “Homo Sapiens” performance piece of 1965, in which he stood for hours like a zoo animal in a cage. A sign identified him as a representative of the human species. In 1968, The Play created a gigantic fiberglass egg, which they released into the ocean near the southernmost tip of Japan’s main island. Ikemizu told a Japanese magazine that “Voyage: Happening in an Egg” offered “an image of liberation from all the material and mental restrictions imposed upon us who live in contemporary times.”

Continue story here

0 notes

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: THE ANTI- MUSEUM : An Anthology (2017) The museum is constantly a target for criticism, whether it comes from artists, thinkers, curators, or even the public. From the avant-gardes of the twentieth century up until our contemporary era, the museum’s suspect position has generated countless gestures, iconoclastic actions, scathing attacks, utopias, and alternative exhibition spaces. For the first time, this anthology is devoted to the anti-museum, through anti-art, the anti-artist, anti-exhibition, as well as anti-architecture, anti-philosophy, anti-religion, anti-cinema and anti-music. This notion – unpatented but regularly reappropriated – traces the erratic, fractured, and sometimes paradoxical counter-history of the contestation of artistic institutions. From the first anti-exhibition to the first catalog retracing the history of “Closed Exhibitions,” from Dada to Noise music, from “Everything is Art” to NO!art, the Japanese avant-gardes to Lettrist cinema, and not forgetting such major protest figures as Gustav Metzger, Henry Flynt, Graciela Carnevale, and Lydia Lunch, The Anti-Museum sketches a polyphonic panorama where negation is accompanied by a powerful breath of life. Edited by Mathieu Copeland and Balthazar Lovay. Introduction by: Mathieu Copeland. Texts by: Zach Blas, Johannes Cladders, Beatriz Colomina, Henry Flynt, Kenneth Goldsmith, Krist Gruijthuijsen, Robert Morris, Bob Nickas, Sören Schmeling, Reiko Tomii, Jon Hendricks, Jean Toche, Andrea Branzi, Ettore Sottsass, Allan Wallach, Guerilla Art Action Group, Robert Morris, Gareth James and many more Features interviews/conversations with John Armleder, Robert Barry, Ben, Genesis P-Orridge, Andrea Branzi, Piero Gilardi, Mierle Laderman Ukeles and many more An incredibly refreshing, valuable, and dense (almost 800 pages) volume, published by Koenig Books and Fia Art. Copies available in the shop this weekend and via our website. #worldfoodbooks #theantimuseum (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: THE ANTI- MUSEUM : An Anthology (2017) The museum is constantly a target for criticism, whether it comes from artists, thinkers, curators, or even the public. From the avant-gardes of the twentieth century up until our contemporary era, the museum’s suspect position has generated countless gestures, iconoclastic actions, scathing attacks, utopias, and alternative exhibition spaces. For the first time, this anthology is devoted to the anti-museum, through anti-art, the anti-artist, anti-exhibition, as well as anti-architecture, anti-philosophy, anti-religion, anti-cinema and anti-music. This notion – unpatented but regularly reappropriated – traces the erratic, fractured, and sometimes paradoxical counter-history of the contestation of artistic institutions. From the first anti-exhibition to the first catalog retracing the history of “Closed Exhibitions,” from Dada to Noise music, from “Everything is Art” to NO!art, the Japanese avant-gardes to Lettrist cinema, and not forgetting such major protest figures as Gustav Metzger, Henry Flynt, Graciela Carnevale, and Lydia Lunch, The Anti-Museum sketches a polyphonic panorama where negation is accompanied by a powerful breath of life. Edited by Mathieu Copeland and Balthazar Lovay. Introduction by: Mathieu Copeland. Texts by: Zach Blas, Johannes Cladders, Beatriz Colomina, Henry Flynt, Kenneth Goldsmith, Krist Gruijthuijsen, Robert Morris, Bob Nickas, Sören Schmeling, Reiko Tomii, Jon Hendricks, Jean Toche, Andrea Branzi, Ettore Sottsass, Allan Wallach, Guerilla Art Action Group, Robert Morris, Gareth James and many more Features interviews/conversations with John Armleder, Robert Barry, Ben, Genesis P-Orridge, Andrea Branzi, Piero Gilardi, Mierle Laderman Ukeles and many more An incredibly refreshing, valuable, and dense (almost 800 pages) volume, published by Koenig Books and Fia Art. Copies available in the shop this weekend and via our website. #worldfoodbooks #theantimuseum (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

1 note

·

View note

Link

Artist: Yutaka Matsuzawa

Venue: Yale Union, Portland

Curated By: Alan Longino, Reiko Tomii

Date: June 30 – August 18, 2019

Note: A text associated with the exhibition written by Alan Longino can be downloaded here.

Click here to view slideshow

Full gallery of images, press release, and link available after the jump.

Images:

Images courtesy of Yale Union, Portland

Press Release:

Yutaka Matsuzawa (1922–2006) was considered the father of Japanese conceptual art. Born in Shimo Suwa in central Japan, he studied architecture during the war, and upon witnessing the after effects of the firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945, he proclaimed upon his graduation from school that he wished “to create an architecture of invisibility.” Once he gave up architecture, he wrote poetry, made paintings, and worked as both an artist and teacher in his hometown. In his pursuit of ways to express the invisible invisibly, Matsuzawa began to develop a unique understanding of conceptual art that both elevated and transcended the typical notions of conceptual art in the western, euro-centric art worlds. However, exhibitions and publications for Matsuzawa in the West have only occurred infrequently, and to this day his work has still not been given the same space for consideration and understanding that many others situated in the West have thus received.

In light of this history, the exhibition at Yale Union will be the first in the U.S. for the artist, and alongside the exhibition the artist’s seminal publication, QUANTUM ART MANIFESTO, from 1988, will be re-published for the first time outside of Japan in an edition of 500. During the exhibition, art historian Namiko Kunimoto will speak on the collaborative work between Yutaka Matsuzawa and the female Butoh dancer, Tsujimura Kazuko.

Alan Longino is an art historian and curator based in Cologne, Germany. His M.A. thesis in Art History from CUNY Hunter College (2017) focused on the event of telepathy within information as the source of image production. His writing has appeared in the Haunt Journal of Art, from UC Irvine.

Reiko Tomii is a New York-based scholar and curator who investigates post-1945 Japanese art as a vital element of world art history of modernisms. She organized exhibitions with Yutaka Matsuzawa until his death in 2006. Her book Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan was published by MIT Press and won the 2017 Robert Motherwell Book Award, which recognizes outstanding publications in the history and criticism of modernism in the arts. The book has recently been turned into an exhibition Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s, currently on view at Japan Society Gallery in New York (through June 9), in which Matsuzawa is prominently featured.

Link: Yutaka Matsuzawa at Yale Union

Contemporary Art Daily is produced by Contemporary Art Group, a not-for-profit organization. We rely on our audience to help fund the publication of exhibitions that show up in this RSS feed. Please consider supporting us by making a donation today.

from Contemporary Art Daily http://bit.ly/33nYltZ

0 notes

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: THE ANTI- MUSEUM : An Anthology (2017) The museum is constantly a target for criticism, whether it comes from artists, thinkers, curators, or even the public. From the avant-gardes of the twentieth century up until our contemporary era, the museum’s suspect position has generated countless gestures, iconoclastic actions, scathing attacks, utopias, and alternative exhibition spaces. For the first time, this anthology is devoted to the anti-museum, through anti-art, the anti-artist, anti-exhibition, as well as anti-architecture, anti-philosophy, anti-religion, anti-cinema and anti-music. This notion – unpatented but regularly reappropriated – traces the erratic, fractured, and sometimes paradoxical counter-history of the contestation of artistic institutions. From the first anti-exhibition to the first catalog retracing the history of “Closed Exhibitions,” from Dada to Noise music, from “Everything is Art” to NO!art, the Japanese avant-gardes to Lettrist cinema, and not forgetting such major protest figures as Gustav Metzger, Henry Flynt, Graciela Carnevale, and Lydia Lunch, The Anti-Museum sketches a polyphonic panorama where negation is accompanied by a powerful breath of life. Edited by Mathieu Copeland and Balthazar Lovay. Introduction by: Mathieu Copeland. Texts by: Zach Blas, Johannes Cladders, Beatriz Colomina, Henry Flynt, Kenneth Goldsmith, Krist Gruijthuijsen, Robert Morris, Bob Nickas, Sören Schmeling, Reiko Tomii, Jon Hendricks, Jean Toche, Andrea Branzi, Ettore Sottsass, Allan Wallach, Guerilla Art Action Group, Robert Morris, Gareth James and many more Features interviews/conversations with John Armleder, Robert Barry, Ben, Genesis P-Orridge, Andrea Branzi, Piero Gilardi, Mierle Laderman Ukeles and many more An incredibly refreshing, valuable, and dense (almost 800 pages) volume, published by Koenig Books and Fia Art. Copies available in the shop this weekend and via our website. #worldfoodbooks #theantimuseum #henryflynt (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

0 notes