#Recueil d'arras

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A long-delayed commission for the kind and extremely patient @branloaf. It's Margaret Tudor, taken from this contemporary sketch here, from the Recueil d'Arras.

#margaret tudor#tudors#art#illustration#tudor dynasty#commissions#painting#traditional painting#16th century#tudor

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meynnart Wewyck’s workshop-part 6: Hidden in Recueil d'Arras

Sorry guys, I realised this months ago, and forgot to post it. In part 1, I mentioned the lost Scottish portraits by Wewyck, done c.1502-1503. They seem to have been lost, and we only have Receuil d’Arras(collection of drawings based upon actual portraits, done in c.1570) which shows us aproximately how they looked like.

We have drawing of James IV, Margaret Tudor, Henry VII and then very rubbed of Elizabeth of York.

But records from 1502 show one extra painting. Of future Henry VIII. It’d be probably THE oldest portrait of him! As child! But it is nowhere to be found. Or have we been looking at it this whole time?

And if you read further I’ll explain you why this drawing from Receuil D’Arras cannot be the Warbeck. 100%.

This is typical handwriting of Le Boucq, found all over the Receuil d’Arras:

And this is text labelling the drawing of Warbeck as him:

Absolutely no way this is the same hand, and I’d wager not even same century. It’s too readable for modern viewer.

Le Boucq didn’t know who it was. He never made any label for drawing. And let me remind you Le Boucq made the drawing about 70 years after Warbeck died. Cca 1570.

How could anybody even later than that recognize it as Warbeck? Based upon what?! It’s impossible!

It was an unknown male whose portrait was part of Scottish royal collection(that is clear because of drawings surounding it. First 21 drawings in Receuil d’Arras were from(in) Scotland, even though not all sitters of those paintings were. Lots of french and english royalty etc. Royalty often sent each other portraits. Long story short, lots of evidence to suggest it truly was Scottish section.)

And based upon it, somebody GUESSED that it is Warbeck!

It’s supposedly the only depiction of him we have surviving!

And it is not him! 100%.

The jewelry, the posture, it fits with Wewyck’s work and Tudor males so well!

Yes, the features are nicer-because kids tend to have softer features and Le Boucq’s drawings also add the softness(such was his style). It fits perfectly with Wewyck’s work. Just look through previous posts.

Also, how would Warbeck’s portrait survive in Scottish royal collection throughout many years Margaret Tudor was the Queen? She’d be certainly outraged at such display. It’s not make sense for her husband to keep the painting of now dead man of whom he had no use.

Like for Tudors it made sense to portray Richard III with broken sword-because that shows him as warrior who was defeated, thus more glory to Tudors for defeating him.(read my post Mistaken identity, if you don’t get why I assume rest of Richard’s portraits are not him.) But same doesn’t apply to Scottish royalty and Warbeck.

In Receuil d’Arras ‘Warbeck’s’ drawing is not even that far from rest of Wewyck’s work.

It’s Henry VII, then Elizabeth of York, then two drawings of Elizabeth I (from late 1550s it seems), then James IV, Margaret Tudor, then Bernard Stewart, 4th Lord of Aubigny; then drawing of Egyptian woman who once healed Scottish King, James II of Scotland and then supposed drawing of Warbeck.

Henry VIII was just 3 drawings away from his sister, the entire time!

Meaning that probably in c.1570, all those paintings were in same chamber or set of chambers when Le Boucq drawn them. They were not separated, even though by that point nobody could remember who the boy in the painting was.

(Probably because those 4 paintings by Wewyck were in same style. So people knew they belonged together. Just no longer who was in one of them.)

That it is boy might also explain why he is much bigger in current drawing than rest of his family. (or at least Le Boucq makes it seems so.)Some painters struggled with proportions of children, adn then sometimes made them ridiculously smaller or much bigger.Even though Margaret would be in her early teens when she got painted, she’d be still couple of years older than her younger brother, thus her features closer to adults.

(That was main information. If you’re interested into me rambling bit more about the other Scottish paintings by Wewyck you can read further. But to be honest i covered lots of it in part 1. If not I hope you’ve enjoyed this.)

Speaking of Margaret I’d like to clerify something. Records suggest she was painted by Wewyck twice. Once as English Princess, and 2nd time already as Quen of Scotland. Idk which one is in Receuil d’Arras.

1)Drawing of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland, based upon portrait from c.1502-3:

But I belive we have idea how 2nd portrait looked. Family trees of James I show Margaret in en face with gable hood:

It’s also in several engravings. Each of them is of not great quality.

The lenght of frontlets and pitch of gable hood suggest it is early 1500s(max.1505), thus likely based upon Wewyck’s work.

I also wanted to point another thing about these scottish-based portraits. They are unique. While there are other depictions where they hold golden orb/apple? and similiar outfit, together all those details don’t fit any other different versions of their portraits surviving, probably because the copies made during Henry VIII’s reign were made based upon portraits located in England.

Thus Scotish located paintings never had copies of them made. So when alongside many other Scottish portraits they got destroyed, Receuil D’Arras became sole source where we can see them. (As far as we know.)

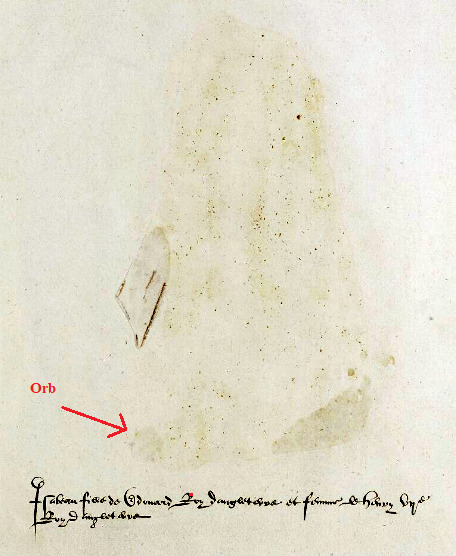

2)Drawing of Henry VII holding an apple/orb:

(Yep it is once again the same brooch-or perhaps there were 2 of same design but different sizes. But same style brooch.)

While even on Henry VII’s drawing some details of the sleeves rubbed off, note the shape of the oufit around his neck. It is round, and the curve goes downward.

And Henry VIII’s paintings go also downward.

But majority of Henry VII’s paintings, have it other way around. They are pointed upward. And it got me thinking-i don’t much about Tudor male fashion in general. So i don’t know their chronological order. However, around 1480 the neckline of english ladies was curve pointing downward(York sisters stained glass), but then through 1490s we saw W-shaped neckline pointing upward, which then slowly returned to almost straight line with slight raise by c.1500 and eventually to completely straight, only to be curved upward much later towards end of Henry VIII’s reign.

I don’t believe they’d send to Scotland painting predating Henry VII’s reign. It’s 1502 painting. No doubt about it.But neckline of men evolved in same way as ladies’ fashion, then big portrion of Henry VII’s paintings would not be from 1500s, but from 1490s, and I don’t mean just late 1490s. Thus potentially Wewyck worked for English royals for much longer than we assumed.

But I don’t have yet enough to establish firmly chronology of dress and headwear prior to 1500. Sadly my only solid source from that time are tomb brasses and dating of those is very difficult and requires lots of time.

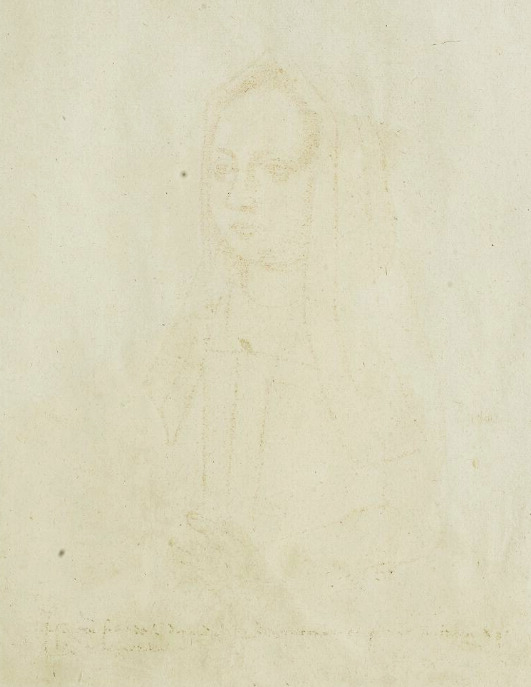

3)Sadly Elizabeth’s sketch is no more there. Sketches are all in pencil and hers sadly got worn out. Only imprint of the original drawing left on the opposite page still survives, but it is really light imprint.@english-history-trip enhanced it a bit(far better than attempt I made and then discarded), but in order to know what that painting looked like, we have to flip it back:

It’s not perfect match with neither of the 5 paintings of her I showed you prior, Currently closest it comes to this:

But why if it is based upon original by Wewyck-from life, why is her neck short?

(In other cases it was in posthumous paintinsg or altered.)

This time there are other possible explanations alterations to the original, le Boucq not gettig proportions right(possibly further shifted by this being based upon imprint) etc. But imo none of those is correct. Imo it’s not alteration. It’s actually there, but isn’t what we think it is(neck crease). Imo it’s edge of necklace.

I had looked at original drawing in Receuil d’Arras, and in Photopea I played with setting to see, if i could find filter or something which would give us better idea of what the drawing looked like. I used both inprint and what is left from original drawing. That is how i discovered that just as Henry she held an orb.

It just stayed on the original page and not on the imprint.

But to get to that necklace, I need to use much stronge filter. Idk what it is called with english, but it turns the drawing into these dots and as you shift the setting, it goes from very dark lines to very light ones-revealing some which you’d never see with naked eye. But it also has downsides. it will hide some lines you’ve seen before and eventually the filter will start to reveal weird lines which are texture of the paper, not related to drawing itself.

Main issue is that some parts are already distorted(because they were visible/more dark before), while some are not, and it is hard to catch the right setting for the era you’re interested in.

However you need to rely on your knowledge of tudor outfit, to connect the dots-literally and to know which dots to not remove.

In this setting hands are not visible, but it is focused exactly on the area of clevage. Thus, while rest needs bit of clearing, that area should be fairly accurate. Now I could be wrong, but that looks like necklace to me.

And you can see it on imprint, in HD, if you focus on it. If you search for it. It’s very very light. But it seems to be there.

Tiny bit of pattern, just under the ‘neck crease) which forms shape of triangles I’d say. It’s not likely to be any of the pearl necklace of triangles we seen in late reign of Henry VIII and later. But some late 15th/early 16th century necklaces had similiar form. One is in Receuil d’Arass itself-on Eleanor of Austria as child:

Royalty in those days often had same jewel makers. Just few provided the jewelry of quality royals wanted(that is why often you see same or similiar jewelry across Europe, on members of several different dynasties and it isn’t just them sending each other gifts.) Also fashion and jewelery back then was not solely unique to the country, they influened each other, and some trends took on in several countries or had pararels in them. (Like french hood’s frill and english gable hood’s paste in early 16th century- they moved up and down around same time.)

Thus Elizabeth’s necklace might have looked similiar to Eleanor’s. Idk exact shape, but it seems to me like top same, then much larger triangles. ANd sometimes it seems like two rows of triangles. Idk.

Unfortunately all my attempts looked horrible. You can try it yourself. I give up.

With hadns also. Can’t make the shape out conclusively. And i can’t make the shape out. But it sort of reminds me of necklace of triangles(which obviously was made much later) or some paintings at turn of 15th and 16th century. Nevertheless this is very underated depiction of her.

(I did look into drawing Henry VII also with these filters-because his is also partially rubbed off. He wears his usual clothes he has in many other portraits. There is nothing new for you to learn there.)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portraits from the Recueil d’Arras, a 16th century collection of images of royalty and other famous personages, attributed to Jacques Le Boucq

1. Henry VII of England

2. Elizabeth of York, Queen of England (This one exists only as an imprint of the original drawing left on the opposite page, so I enhanced it a bit to make it more visible)

3. James IV of Scotland

4. Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

5. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, brother of Henry V of England

6. Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy

7. Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France (Incorrectly labeled as Charlotte of Savoy)

8. James (I or II) of Scotland (Labeled only as “James, King of Scots”)

9. Mary I of England (Labeled as Elizabeth I, but I think it’s Mary because I’ve only ever seen that triangle hood on her)

10. Elizabeth I of England

Check out the entire digitized manuscript, featuring a total of 293 portraits, here!

#this thing rocks so hard#they're mainly copies of contemporary portraits#and we know they're largely accurate because some of the original portraits have survived to compare them to#definitely gonna do a second post#manuscript#tudors#plantagenets#stewarts#art history#Recueil d'arras

200 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Historical Objects: Sixteenth Century Portrait of a Romani Woman from the Recueil d’Arras

The Recueil d’Arras- a collection of sketches of notable historical figures probably produced by the Hainaulter Jacques le Boucq in the mid-sixteenth century- is a fascinating work to anyone interested in Scottish history, not least for its sketches of members of the Scottish royal family, mostly taken from contemporary portraits which have no longer survived. Possibly one of the most intriguing pieces associated with Scotland though, is not of a king or princess, but of an ordinary woman of the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, described in the recueil as “L’Egyptienne quy rendist santé part art de médecine au roy d’Escoce abandonné des medecins”- i.e. “The Egyptian woman who by medical art restored health to the King of Scotland, given up by physicians”. The recueil does not specify WHICH king of Scots this skilful woman is supposed to have saved, although the sketch is placed between two portraits of Scottish monarchs (one which may either be James I or James II, and another of James IV). The story might even be entirely fanciful, but it is nonetheless an interesting piece of anecdotal evidence, while the woman’s costume tallies with other sixteenth century portrayals of Romani women wearing turbans and cloaks.

It is unclear whether this particular lady was resident in France or Scotland (the possibility that the miraculous healing of a King of Scots relates to James V’s visit to France in 1536-7 cannot be ruled out, given the Recueil’s provenance), but there has certainly been a Romani community in Scotland since at least the early sixteenth century, distinct from other Scottish travellers. Royal and civic documents of the time contain several references to “Egyptians” (the general term of the time, despite their actual origin in what is now India), including some famous names like that of John Faa, whose posthumous reputation, though far exceeding the historical evidence for his life, pays testament to the importance of the Romani community in Scottish culture and history across the centuries, despite frequent persecution. If this sketch does indeed depict a real woman, whether resident in France or Scotland, we are incredibly fortunate in its survival, but even if the story is more myth than history, the portrait is an interesting piece of evidence for both Romani history of the sixteenth century and contemporary perceptions of Romani dress and cultural roles.

Sources below cut.

References:

I wasn’t able to find much certain information about this painting, nor was I able to find many available images online so I am much in debt to this article by Angus Fraser, “The Gypsy Healer and the King of Scots”, in the “Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society” (now entitled “Romani Studies”- and can you believe that the University of Liverpool have published almost all of its issues online free!

Otherwise I was reliant on the reference in Andrea Thomas’ “Glory and Honour” which initially directed me to the sketch. Generally if anyone wants to find some more primary sources about the Romani community (or communities) in sixteenth century Scotland, I would suggest making a start with the usual registers of the privy seal, Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer, Acts of the Lords of Council, and various burgh records from Scotland’s towns, bearing in mind that these sources will inevitably be biased.

And if anyone can recommend any good and trustworthy sources to me in turn, or offer some pointers as to where I may have gone wrong (pretty sure some of my terminology is confused), please do! It is not my area of expertise at the moment, and I’d like to research something a bit more meaty than a portrait of dubious origin, but it was hardly an aspect of Scottish history that could be left out of any self-respecting blog.

#Scottish history#art history#Romani history#British history#women in history#art#Recueil d'Arras#France#Jacques le Boucq#Living in Medieval Scotland#sixteenth century#Romani#women#medicine#historical objects#healing#folklore#(?)#fashion history#sort of anyway#immigration#people

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arbalétrier Demi-Elfe

Vous voulez retrouver la fiche de personnage ?

Unali Jomaris est une demi-elfe qui a choisi la voie martiale de l’Arbalétrier.

La fiche de personnage pour Chroniques Oubliées est ici : https://scriiipt.com/download/53454/

L’Arbalétrier historique

L'arbalétrier est un soldat de l'armée féodale muni d'une arbalète. Il fut très largement utilisé par les Français, lors des Croisades et de la guerre de Cent Ans, souvent comme mercenaire principalement génois (recruté à Gênes et dans diverses villes et pays du nord-ouest de l'Italie).

Son emploi en rase-campagne était médiocre, dû essentiellement à la lenteur du rechargement de l'arbalète et s'avérait donc plus efficace lors des sièges. Richard Cœur de Lion mourut ainsi au siège de Châlus et Jeanne d'Arc fut blessée d'un carreau en assiégeant Paris.

Le cranequinier est un arbalétrier muni d'une arme dont l'arc (composite ou en acier) nécessite un appareil puissant et mobile pour le tendre. Les cranequiniers servaient à pied ou à cheval selon le moyen de tension utilisé. Les cranequiniers à cheval tiraient et retendaient leur arme depuis leur selle, comme en atteste notamment la bataille de Montlhéry en 1465.

Le pavesier est un valet muni de grands boucliers (terges, pavois) protégeant les arbalétriers.

Maître arbalétrier : l’office de Maître des arbalétriers était considérable en France dès le temps de Saint Louis. Il avait le commandement sur les gens de pied. Du Tillet dans son Recueil des Rois de France et de leur couronne, chapitre des Connétables, sur le fin, et Pasquier dans ses Recherches, disent qu’il était ainsi nommé, parce que les arbalétriers étaient les plus estimés entre les gens de pied, les principales forces des armées françaises constituant en archers et arbalétriers. Le premier de ces auteurs ajoute que c’était un office et non une commission, et que le colonel de l'infanterie lui a succédé. Il avait encore la surintendance sur tous les offices qui avaient charge pour les machines de guerre avant l’invention et usage de la poudre et de l’artillerie. Il est difficile d’établir plus précisément en quoi consistaient ses fonctions et son autorité et dans quel temps il a été connu sous le titre de « Grand Maître des Arbalétriers ». Ce que l’on a de plus certain est que sur un débat entre le Maréchal de Boucicault et Jean sire de Hangest, dans lequel les arbalétriers, archers et canonniers soutenaient qu’ayant pour supérieurs les Maîtres des arbalétriers et de l’artillerie, ils n’étaient point dépendants des maréchaux de France. C’est le 22 avril 1411, que le roi Charles VI de France jugea qu’ils étaient et demeureraient à toujours sous la charge des maréchaux au fait de la guerre. Une des premières références d’un Maître arbalétrier sous Saint Louis remonte à février 1233, dans un acte en latin confirmant une rente pour les héritiers de feu « Illustre Maître des arbalétriers Jean de Surie », originaire de Lorris-en-Gâtinais (Loiret).

Histoire

On parle pour la première fois de la milice des arbalétriers en France sous Louis le Gros. Le deuxième concile de Latran interdit l'arbalète comme une invention trop meurtrière. Richard Cœur de Lion et Philippe-Auguste ne tinrent pas compte : les arbalétriers rendirent de grands services à la bataille de Bouvines (1214). Bientôt ils eurent un Grand-Maître.

Les compagnies d'arbalétriers de Rouen, Tournai et Paris, servirent de modèle à celles qui se formèrent dans les villes du Nord de la France, à Laon, Beauvais, Compiègne, Béthune, etc. On tenait à honneur d'entrer dans ces compagnies. Du Guesclin était de celle de Rennes.

Les changements introduits au XVème siècle dans l'organisation militaire ne firent pas complètement disparaître les arbalétriers. Une compagnie fit merveille à Marignan sous François Ier de France ; d'autres aidèrent Bayard à défendre Mézières contre les Impériaux ; les arbalétriers de Crépy combattirent à Saint-Quentin avec Coligny ; ceux de Montdidier repoussèrent le grand Condé en 1653 ; les compagnies de Picardie prirent part, sous Louis XIV, aux sièges de Saint-Omer, d'Arras et de Dunkerque. Mais, en général, jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIème siècle, les arbalétriers ne servirent qu'à maintenir le bon ordre dans les villes.

0 notes

Photo

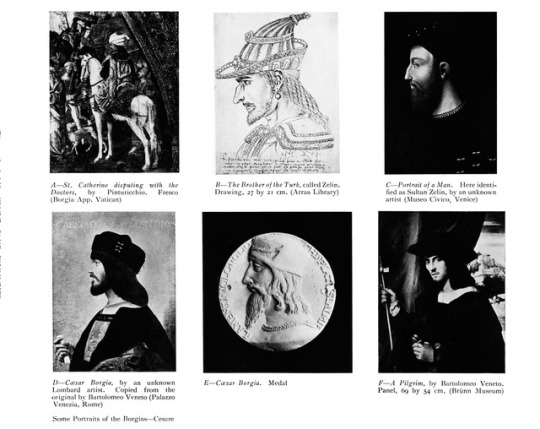

Warning: the article is overly influenced by the black legend. Anyway, it’s interesting and worth a look, especially for the inscription round the medal made after Valentino’s downfall.

Caesar Borgia was the most feared man of his time. Murder was his pastime and also his business. He decreed the assassination of his own brother, the Duke of Gandia, and even threatened his own father with death. Alexander VI trembled before him, and yet loved him. Cruelty seemed quite natural in those days. The condottieri did not value their own lives; still less the lives of others. And yet Cesare was a coward. He did not assassinate his victims himself, but preferred to pay others to do so. Many of those rough Italian warriors had good human qualities: capacity for love and friendship, taste for poetry, architecture and gardens. Cesare loved nothing but gold and rich clothing. By a curious irony of fate, this barbarous personage had for a whole year in his service an engineer named Leonardo da Vinci, a man indifferent to everything but the highest flights of thought and art. During this year he wrote to a friend: “Do not pity me; I am not poor; poor only is he who desires many things.” Cesare, on the contrary, was ever eager to accumulate more and more land, more and more gold. This avaricious noble was a past master of the art of advertising. His purpose was to become known and feared throughout Europe. And in fact, he attained a wide-spread notoriety; he was as popular as Charlie Chaplin in our days and he was at the same time despised like Herod. His fame spread as rapidly as that of a popular actor and died down just as quickly. Born on the steps of a papal throne, he enjoyed papal wealth and power, but was not able to maintain his position after the death of his father, Pope Alexander VI. He was imprisoned in Rome, sent to Spain and remained there two years in captivity. He then escaped, but was killed in a night action in 1507 near Vienna. A few years afterwards, by order of the Bishop of Pampeluna, who thought that such an evil man should not even receive burial, his bones were thrown out of his tomb. The body of the man, who filled so many coffins, lay unburied. The story of his life lived on in the minds of the people, vague and fantastic as a popular legend. What was he like, this extraordinary man? The cavalier in the background of Pinturicchio’s fresco in the Borgia apartments is not Cesare Borgia, as is generally supposed, but the truth is that the son of Alexander VI was subsequently confused with one of his most famous victims. About 1482, Djem, younger brother of the Emperor Bajareth, fled to Rhodes, came afterwards to France, and was sent to Rome in 1489. He was received there with honours. Whenever he appeared in the train of the Pope, his remarkable face, his perfect horsemanship, and the magnificence of his oriental garments were much admired. Pinturicchio gave to this picturesque Oriental gentleman a prominent place in his picture St. Catherine disputing with the Doctors. There is no doubt that the warrior on a white horse is Prince Djem [PLATE A], as stated in a sketch book of the sixteenth century, entitled the “Recueil d'Arras,”’ in which appears the same eagle-faced [PLATE B]. Djem introduced the fashion of eastern coats into Rome. Cesare was envious of his success and imitated his style of dress. The citizens of Rome were scandalized when the son of the Pope appeared in solemn processions arrayed in oriental garments and wearing a large white turban like a Turk. In the eyes of Bajareth, this brother, living so far away in the midst of Christians, was an ever- present danger. In 1496, the Sultan offered three hundred thousand pieces of gold to Alexander VI, asking him by letter to send his brother “ to a better land.” Soon afterwards, the army of Charles VIII conquered Rome. The King of France, Prince Djem and Cesare all rode together to Naples. On the way, Cesare escaped. A few days later, the Oriental nobleman died a mysterious death, and it subsequently transpired that Cesare was richer by a hundred thousand pieces of gold–the amount promised by Bajareth to the murderer of his brother. It comes as a surprise after this story to find in the Museo Civico in Venice the portrait of the victim over the name of his murderer. It is the same face as that of the “Recueil d'Arras,” only the hair is dressed in Italian fashion, a fine net keeping it together, as in many portraits of that time [PLATE C]. As a matter of fact, there was a certain resemblance between the two men, Djem and Cesare. The difference consisted in the finer profile and aquiline nose of the Turk, while Cesare had quite a straight nose and the contours of his face were rather heavy and effeminate. The inscription round a medal made after his downfall, runs as follows: Volgi. Gliochi. Piatosl. Amiie Lamenti. And on the reverse side, round the figure of Fortune with a sail riding on a dolphin, we read: Poche. Fortuna. Vole. Che. Cosi Tstenti (Turn thy compassionate eyes to my lamenting, since it is Fortune’s will to be so niggardly) [PLATE E]. Here we see him as he really was, and this medal affords further proof that the original of the portrait by Bartolomeo Veneto was indeed the son of Alexander VI. We find a copy made after the lost original of this painting in the Palazzo Venezia in Rome. It shows the Duke in profile, holding a roll of documents in his right hand [PLATE D]. The inscription is as follows: Caes. Borgia Valentinus. Bartolomeo Veneto was a portrait painter only in the latter part of his life. He painted some simple portraits in his youth when he worked in the studio of Giovanni Bellini. Such an early work may be seen in a Munich private gallery. But, as mentioned above, his fame as a portrait painter came later. He became one of the most remarkable portraitists of Italy, with a wonderful capacity for catching a likeness. He was most careful in reproducing every detail of costume, and yet there was nothing finicky about his pictures. His models also are fascinating: thoughtful young gentlemen clad in rich garments. In Brummel’s epoch, a dandy had to appear indifferent and insolent; in the Renaissance, a dreamer. These magnificent young people, who had their portraits painted by Veneto, were students of the Padua University. We are able to establish this fact by means of a recently acquired picture by Bartolomeo Veneto in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, representing Hieronymus Dondi, a young patrician of Padua. The sojourn of Bartolomeo in Padua had the greatest influence upon his development. Padua was at this time the Oxford of Christendom. The education of a nobleman was not complete if he had not studied for some years at this university. The most eminent young humanists of every country met there. For some time, Bartolomeo Veneto made his home in Padua, probably after 1517, because from 1509 to 1517, the university was closed on account of the war between the Emperor Maximilian and the Venetians. There Bartolomeo made the acquaintance of several young noblemen, painted their portraits, and remained their friend. He was a welcome guest in the chateaux of Northern Italy. He painted some of his friends in their first youth, and then again in later years. It may be that one of his hosts asked him to paint some portraits of the Borgias for his picture gallery. But it is also possible that some member of the Court of Ferrara entrusted him with this work. Unfortunately, the original of Bartolomeo’s Cesare Borgia is lost. A genuine painting by the artist of the same period, and signed by him, is the Pilgrim in the Briinn Museum [PLATE F]. This makes us regret all the more that we no longer possess the original of his Cesare Borgia, which must have been a great work. But how was it possible that Bartolomeo Veneto had the cruel condottiere as a model? The painter came to Ferrara in 1505. The year before, Cesare left Italy for ever. So Bartolomeo could never have seen Cesare Borgia. Nevertheless, he stayed for a long time at the court of his sister. The only deep feeling of which that ambitious and superficial creature was capable was affection for her brother. When Lucrezia received the news that Cesare had been killed, she retired for a long time to a convent, profoundly affected. In her palace, Bartolomeo must certainly have seen portraits and medals of the Duke of Valentinois, and heard a great deal about him, so, with the sensitiveness of a real artist, was able to produce a true portrait of a man he never saw. Bartolomeo painted Lucrezia long after he had left her house, and he became the painter of Cesare whom he never met.

Source: The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 61, No. 353 (Aug., 1932), pp. 70+74-75

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hey! Wanna see some realistic contemporary-adjacent portraits of people from the past? Curious about who a 16th century Belgian man might consider worthy of note? Just down to see some ROCKIN’ HATS?

Come on down to the Wikipedia page for the Recueil d’Arras, which I just spent two solid days updating with over 190 missing portraits. (I died some time ago.) (The Wikipedia page is in French, so you’ll have to have Translate on, or know French.)

#I love octopus hat up there#but I think my favorite might be little Catherine of Egmont in the no 7 slot there#she looks like she walked out of the 1920s#anyway hats hats hats#I genuinely dreamed in pencil sketches last night#fashion history#art history#Manuscript#Recueil d'arras

141 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some of my Recueil d’Arras coloring pages completed!

(These are Yolande, illegitimate daughter of Philip III of Burgundy, Margaret Tudor, and Jacqueline of Hainaut.)

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking at the very interesting https://ladyjanegreyrevisited.com/, as well as http://somegreymatter.com/, alerted me to a development in the world of the portraiture of Elizabeth I, specifically the rediscovery of this portrait, which resurfaced at auction last year:

It's one along the lines of the classic Clopton Portrait, which was produced early in her reign before she began to control the strict iconography of her public image.

The similarities are clear, but so are the differences: the front-facing pose, the jewelry, the headdress. But I immediately thought of a different comparison, this pencil copy of an unknown portrait of the queen:

This is from the Recueil d'Arras, a compendium of hundreds of copies of portraits of nobility from around Europe. Most of the original portraits have been lost, which makes it a great resource, but the few that have survived show the accuracy of the drawings.

With this in mind, the fashion and posture between the two Elizabeth portraits can be believed:

The clearest differences are the rounded face and the necklace of the first portrait. My theory is that these are later, possibly Victorian additions. There is a history of Victorians altering portraits to be more "marketable", smoothing out features and adding/removing elements to conform to a Victorian style of beauty:

Perhaps the fur and ruff were altered, and the necklace added, to further identify the portrait with Elizabeth; certainly she is not shown wearing strings of knotted pearls until much later in her reign. I'd be very interested for them to run an x-ray on it!

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, remember the Recueil d'Arras, the collection of sketches of various medieval and renaissance figures? Turns out it's got a baby sister: the Memoriaux d'Antoine de Succa. Succa was appointed by Albert and Isabella of Austria in 1600 to document the portraiture of the ruling houses of Austria, Burgundy, Brabant and Flanders. He copied largely funerary monuments, noting details like color and materials, and the work exists as the only record for some of these since lost monuments. Those which have survived attest to the accuracy of his drawings.

It's a little harder to navigate, since it hasn't been transcribed to Wikipedia, but the digitized manuscript is still fascinating to page through. You can also follow along in this catalog for descriptions, but it is in French.

(Pictured above are Michelle of Valois, Jacqueline of Hainaut, Baldwin V of Hainaut and Margaret of Flanders, Blanche of Sicily, Catherine of France, Catherine of Burgundy, John I of Cleves, and Marie of Savoy.)

#some of these are pretty anachronistic but that wasn't his fault#he was just copying them#like baldwin and margaret there are from the 12th century and no one was wearing that#art history#fashion history#manuscript

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting started on my Recueil d'Arras coloring pages!

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Recueil d'Arras is a mid-16th century manuscript.

Tentatively attributed to the Netherlandish artist Jacques Le Boucq, it comprises 293 paper folios, of which nrs 5–177, 179–293 and 271 contain 289 copies of drawn portraits of named historical people.

The book is named after the city of its current location, Arras, located in Northern France.

It is not known who commissioned the book, or for what purpose.

Portraits from the Receuil d’Arras, a 16th century collection of images of royalty and other famous personages, attributed to Jacques Le Boucq

1. Henry VII of England

2. Elizabeth of York, Queen of England (This one exists only as an imprint of the original drawing left on the opposite page, so I enhanced it a bit to make it more visible)

3. James IV of Scotland

4. Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

5. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, brother of Henry V of England

6. Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy

7. Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France (Incorrectly labeled as Charlotte of Savoy)

8. James (I or II) of Scotland (Labeled only as “James, King of Scots”)

9. Mary I of England (Labeled as Elizabeth I, but I think it’s Mary because I’ve only ever seen that triangle hood on her)

10. Elizabeth I of England

Check out the entire digitized manuscript, featuring a total of 293 portraits, here!

200 notes

·

View notes