#Queen Blanche of France

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Philip II Augustus (1165-1223), Louis VIII (1167-1226), Blanche of Castile (1188-1252), Louis IX (1214-1270) and Margaret of Provence (1291-1295). By Felix Fossey.

#felix fossey#royaume de france#capétiens#philippe ii auguste#louis viii#blanche de castille#louis ix#st louis#st louis ix#marguerite de provence#roi de france#vive le roi#full length portrait#kingdom of france#queen consort#reine de france#vive la reine#outremer#crusades#crusaders

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Reine Blanche de Castille et son fils Saint Louis

#Blanche de Castille#saint louis#st louis#louis ix#louis 9#roi de france#moi je dis roy de Franc#king of france#france#french history#aquarelle#watercolour art#art#queen of france#queen

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche, Marguerite, and Queenship

Blanche's actions as queen dowager amount to no more than those of her grandmother and great-grandmother. A wise and experienced mother of a king was expected to advise him. She would intercede with him, and would thus be a natural focus of diplomatic activity. Popes, great Churchmen and great laymen would expect to influence the king or gain favour with him through her; thus popes like Gregory IX and Innocent IV, and great princes like Raymond VII of Toulouse, addressed themselves to Blanche. She would be expected to mediate at court. She had the royal authority to intervene in crises to maintain the governance of the realm, as Blanche did during Louis's near-fatal illness in 1244-5, and as Eleanor did in England in 1192.

In short, Blanche's activities after Louis's minority were no more and no less "co-rule" than those of other queen dowagers. No king could rule on his own. All kings- even Philip Augustus- relied heavily on those they trusted for advice, and often for executive action. William the Breton described Brother Guérin as "quasi secundus a rege"- "as if second to the king": indeed, Jacques Krynen characterised Philip and his administrators as almost co-governors. The vastness of their realms forced the Angevin kings to rely even more on the governance of others, including their mothers and their wives. Blanche's prominent role depended on the consent of her son. Louis trusted her judgement. He may also have found many of the demands of ruling uncongenial. Blanche certainly had her detractors at court, but she was probably criticsed, not for playing a role in the execution of government, but for influencing her son in one direction by those who hoped to influence him in another.

The death of a king meant that there was often more than one queen. Blanche herself did not have to deal with an active dowager queen: Ingeborg lived on the edges of court and political life; besides, she was not Louis VIII's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine did not have to deal with a forceful young queen: Berengaria of Navarre, like Ingeborg, was retiring; Isabella of Angoulême was still a child. But the potential problem of two crowned, anointed and politically engaged queens is made manifest in the relationship between Blanche and St Louis's queen, Margaret of Provence.

At her marriage in 1234 Margaret of Provence was too young to play an active role as queen. The household accounts of 1239 still distinguish between the queen, by which they mean Blanche, and the young queen — Margaret. By 1241 Margaret had decided that she should play the role expected of a reigning queen. She was almost certainly engaging in diplomacy over the continental Angevin territories with her sister, Queen Eleanor of England. Churchmen loyal to Blanche, presumably at the older queen’s behest, put a stop to that. It was Blanche rather than Margaret who took the initiative in the crisis of 1245. Although Margaret accompanied the court on the great expedition to Saumur for the knighting of Alphonse in 1241, it was Blanche who headed the queen’s table, as if she, not Margaret, were queen consort. In the Sainte-Chapelle, Blanche of Castile’s queenship is signified by a blatant scattering of the castles of Castile: the pales of Provence are absent.

Margaret was courageous and spirited. When Louis was captured on Crusade, she kept her nerve and steadied that of the demoralised Crusaders, organised the payment of his ransom and the defence of Damietta, in spite of the fact that she had given birth to a son a few days previously. She reacted with quick-witted bravery when fire engulfed her cabin, and she accepted the dangers and discomforts of the Crusade with grace and good humour. But her attempt to work towards peace between her husband and her brother-in-law, Henry III, in 1241 lost her the trust of Louis and his close advisers — Blanche, of course, was the closest of them all - and that trust was never regained. That distrust was apparent in 1261, when Louis reorganised the household. There were draconian checks on Margaret's expenditure and almsgiving. She was not to receive gifts, nor to give orders to royal baillis or prévôts, or to undertake building works without the permission of the king. Her choice of members of her household was also subject to his agreement.

Margaret survived her husband by some thirty years, so that she herself was queen mother, to Philip III, and was still a presence ar court during the reign of her grandson Philip IV. But Louis did not make her regent on his second, and fatal, Crusade in 1270. In the early 12605 Margarer tried to persuade her young son, the future Philip III, to agree to obey her until he was thirty. When Philip told his father, Louis was horrified. In a strange echo of the events of 1241, he forced Philip to resile from his oath to his mother, and forced Margaret to agree never again to attempt such a move. Margaret had overplayed her hand. It meant that she was specifically prevented from acting with those full and legitimate powers of a crowned queen after the death of her husband that Blanche, like Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been able to deploy for the good of the realm.

Why was Margaret treated so differently from Blanche? Were attitudes to the power of women changing? Not yet. In 1294 Philip IV was prepared to name his queen, Joanna of Champagne-Navarre, as sole regent with full regal powers in the event of his son's succession as a minor. She conducted diplomatic negotiations for him. He often associated her with his kingship in his acts. And Philip IV wanted Joanna buried among the kings of France at Saint-Denis - though she herself chose burial with the Paris Franciscans. The effectiveness and evident importance to their husbands of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile in England led David Carpenter to characterise late thirteenth-century England as a period of ‘resurgence in queenship’.

The problem for Margaret was personal, rather than institutional. Blanche had had her detractors at court. It is not clear who they were. There were always factions at courts, not least one that centred around Margaret, and anyone who had influence over a king would have detractors. They might have been clerks with misgivings about women in general, and powerful women in particular, and there may have been others who believed that the power of a queen should be curtailed, No one did curtail Blanche's — far from it. By the late chirteenth century the Capetian family were commissioning and promoting accounts of Louis IX that praise not just her firm and just rule as regent, but also her role as adviser and counsellor — her continuing influence — during his personal rule. As William of Saint-Pathus put it, because she was such a ‘sage et preude femme’, Louis always wanted ‘sa presence et son conseil’. But where Blanche was seen as the wisest and best provider of good advice that a king could have, a queen whose advice would always be for the good of the king and his realm, Margaret was seen by Louis as a queen at the centre of intrigue, whose advice would not be disinterested. Surprisingly, such formidable policical players at the English court as Simon de Montfort and her nephew, the future Edward I, felt that it was worthwhile to do diplomatic business through Margaret. Initially, Henry III and Simon de Montfort chose Margaret, not Louis, to arbitrate between them. She was a more active diplomat than Joinville and the Lives of Louis suggest, and probably, where her aims coincided with her husband’s, quite effective.

To an extent the difference between Blanche’s and Margaret’s position and influence simply reflected political reality. Blanche was accused of sending rich gifts to her family in Spain, and advancing them within the court. But there was no danger that her cultivation of Castilian family connections could damage the interests of the Capetian realm. Margaret’s Provençal connections could. Her sister Eleanor was married to Henry III of England. Margaret and Eleanor undoubtedly attempted to bring about a rapprochement between the two kings. This was helpful once Louis himself had decided to come to an agreement with Henry in the late 1250s, but was perceived as meddlesome plotting in the 1240s. Moreover, Margaret’s sister Sanchia was married to Henry's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, who claimed the county of Poitou, and her youngest sister, Beatrice, countess of Provence, was married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia’s interests were in direct conflict with those of Alphonse of Poitiers; and Margaret herself felt that she had dowry claims in Provence, and alienated Charles by attempting to pursue them. Indeed, her ill-fated attempt to tie her son Philip to her included clauses that he would not ally himself with Charles of Anjou against her.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#grégoire ix#innocent iv#raymond vii de toulouse#aliénor d'aquitaine#louis ix#philippe ii#guérin#louis viii#marguerite de provence#aliénor de provence#alphonse de poitiers#henry iii of england#philippe iii#jeanne i de navarre#philippe iv#simon de montfort#edward i of england#jean de joinville#sancia de provence#béatrice de provence#charles i d'anjou

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Next on the list of Snow White tales in the book Sleeping Beauties: Sleeping Beauty and Snow White Tales From Around the World are the versions from France and Italy.

*The first of the three French tales is The Lay of Eliduc, composed by a medieval woman poet, Marie of France. It's not really a Snow White story, but it does feature a beautiful princess in a deathlike trance. A knight, Eliduc, is unjustly banished by his king, and forced to travel to another kingdom, where he helps the local king to win a war. During this time, he falls in love with the king's daughter, Guillardun, and she with him... but unfortunately, he already has a good, faithful wife, Guildeluec, back in his homeland, and is torn between his new love and old love. When Guillardun learns that Eliduc is already married, she falls into a swoon from which nothing can revive her. Distraught, Eliduc lays her to rest in a chapel in the woods, which he frequently visits from then on, even after he goes back to his wife. Guildeluec sets out to learn the cause of her husband's mysterious sadness, and discovers the chapel and Guillardun lying inside it. Then, in a detail that evokes the Grimms' tale of The Three Snake Leaves, she sees a weasel use a certain flower to bring its dead mate back to life – she uses the flower to bring Guillardun back to life too. After the whole story is revealed, Guildeluec graciously leaves her husband and becomes a nun, allowing Eliduc and Guillardun to marry.

**Besides the tale itself, the book includes an essay which highlights the parallels between this story and the Celtic Snow White tale of Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree, which will be overviewed later. The author suggests that Marie of France may have heard a variant of Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree and drawn inspiration from it.

*The book also includes two other French Snow White tales: The Mirror and The Stepmother.

**The Mirror is nearly identical to the Grimms' Snow White (a wicked queen stepmother, a magic mirror, a poisoned apple, etc.) with two chief exceptions. (1) Instead of seven dwarfs in a cottage, the heroine, Blanche, comes to live with seven giants in a castle. (2) The details of the ending. Some time after Blanche's "death," a royal wedding is held in another kingdom, and the seven giants are invited. Rather than leave Blanche's glass coffin unprotected, they carry it with them, but on their way they accidentally drop and shatter it, jarring the piece of apple from Blanche's mouth and reviving her. She then goes with the giants to the wedding, where, as it happens, her father and stepmother are guests too. Blanche reunites with her father and accepts the marriage proposal of a prince who also attends, while the queen is forced to dance to death in hot iron shoes.

**In The Stepmother, the heroine isn't a princess, but an innkeeper's daughter, and her jealous stepmother convinces her weak-willed father to abandon her, a la Hansel and Gretel. She meets a band of thieves who take her in. But sometime later, she shows kindness to an old beggar woman, who is really a wicked witch, and who offers to comb her hair, only to stick a magic pin into her head that freezes her in place like a statue. (Strangely, there's no mention of any connection between this witch and the stepmother.) The heartbroken thieves keep the "statue" on display in their house, until one day a prince discovers her, falls in love, and takes her back to his castle, where he secretly keeps her in his room. But one day the prince's sister discovers the "statue," tries to comb its beautiful hair, and takes out the pin, bringing the heroine back to life. The prince and the heroine are joyfully wed and have twins. But soon the prince is forced to go to war; while he's away, the wicked stepmother forges a letter from him and sends it to the castle, demanding that his wife and children be banished. But in the woods with her children, the heroine prays, and miraculously a house springs up for the three of them to live in, until in the end the prince finds them.

*I've also read another French variant, La petite Toute-Belle, which isn't included in this book. In that tale, the heroine is pushed down a well (evoking Mother Holle) by her wicked mother's servant, lands in the home of three friendly dragons, is later poisoned with a dress, then set afloat on the sea in her coffin, and washes up near the castle of a young king, whose mother takes off the dress and revives her. Why Heiner left it out of her collection I don't know.

Next come a long list of variations from Italy.

*The first is The Young Slave from Giambattista Basile's Il Pentamerone, which is often labeled a Snow White story, though it's really more of a cross between Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, and The Goose Girl. A group of young maidens, including a baron's sister, have a contest to see who can jump over a rosebush without damaging the single rose on it. The baron's sister knocks off just one rose petal, but she secretly swallows it so no one will know. As a result, she gives birth to a baby girl, whom she names Lisa, and whose birth she keeps a secret from everyone except the fairies because there's no father. As in Sleeping Beauty, the fairies each give Lisa a blessing, but one fairy twists her ankle while running to the cradle, and in her pain she curses Lisa to die at age seven when her mother accidentally leaves a comb stuck in her hair. Sure enough, seven years later, it happens. Rather than bury Lisa, the distraught mother places her in the innermost of seven crystal chests, which she hides in a secret room in her brother's castle. She then falls ill with grief and dies, on her deathbed warning her brother never to look inside that room. Some time later, the baron marries, and warns his wife never to look in the secret room either. But of course, out of curiosity, she does, and she finds the dead Lisa grown into a beautiful maiden. In a jealous rage she grabs Lisa's hair, and in doing so she dislodges the comb and revives her. Then she dresses her in rags, forces her to work as a slave, and constantly abuses her. But eventually, the baron goes on a journey and asks all the castle servants for gift requests, including Lisa, whom he doesn't know is his niece. Lisa asks for a doll, and when she gets it, she tells her troubles to it every day. Finally, the baron overhears her and learns her true identity. The cruel wife is sent away, and the baron becomes Lisa's guardian and eventually finds a good husband for her.

*As for the other Italian versions, there are too many to summarize each one, so I'll just overview the details:

**The heroine is typically a commoner, not a princess. As in The Stepmother from France, her wicked mother or stepmother is sometimes an innkeeper, who learns of the heroine's survival from travelers to the inn who saw her.

**Only a few of these versions have the villainess be the heroine's own mother. The majority seem to feature a stepmother, and several follow the pattern seen in some Cinderella stories from the same region, where she starts out as the heroine's seemingly-kind teacher, whom the girl persuades her father to marry. In a few versions, however, the heroine is persecuted by two older sisters.

**Some versions include a magic mirror, while others have the heroine's survival and whereabouts reported by a bird, an animal, or a beggar whom she was kind to.

**Two versions introduce the prince at the very beginning, and have him visit the three sisters and be smitten by the youngest while slighting the older two. This takes the place of the mirror proclaiming her the fairest in the land.

**There typically isn't a huntsman figure. The villainess usually just abandons the heroine in the wilds, or has a maidservant do it, or else convinces the girl's father to do it, Hansel and Gretel-style.

**The counterparts of the seven dwarfs vary widely. Sometimes they're fairies, sometimes a band of thieves, in one version an ogre and his wife, and in another just a kindly old man. In two versions, it's a dead lady trapped on earth in her castle as a form of purgatory, whom the heroine cares for until her sins are expiated and she rises to heaven; unfortunately, her ascent happens just before the last attempt on the heroine's life, so she's not there to warn her about the poison the way she was before. In yet another Italian version I've read that isn't included here, Giricoccola, the heroine's helper is the moon, who lifts her out of the attic where her jealous sisters have imprisoned her and carries her away to her heavenly castle.

***In the versions with the thieves, the heroine typically hides in their house for the first few days, eating, drinking, and cleaning the house while they're away, much to their confusion when they come home. But soon they discover her and welcome her into their family.

**The villainous mother, stepmother, or sisters typically don't practice witchcraft themselves in these versions, but consult a witch, who creates the poisoned items for them.

**The poisoned item that finally "kills" the heroine is almost always an article of clothing: e.g. a dress, a hat, a hairpin, or a pair of slippers. In some versions she simply falls down dead or in an enchanted sleep, while in other versions she becomes motionless like a statue, or actually turns to stone. But either way, the prince typically finds her, falls in love, and takes her home to his castle, where he lets no one else inside the room where he keeps her. But then one day a woman – his mother, his sister, or a servant – sneaks in, discovers the girl, and tries to make her look more presentable, removing the poisoned item in doing so. Her revival becomes a joyful surprise for the prince when he comes home.

***Only one version, The Beautiful Anna, has the heroine poisoned by a grape, which the prince later dislodges from her throat by stroking her beautiful neck while admiring her.

***Several versions use poisoned food (usually cake or sweets) for the first one or two murder attempts. But either the heroine is warned not to eat it, or else an animal eats it first and dies. It's an interesting contrast to the familiar Grimms' version, where the queen's first two attempts to kill Snow White with articles of clothing fail because they're easily removed, so she turns to the more seemingly foolproof method of poisoned food for the third try.

**In the versions where the heroine "dies" rather than becoming a statue, she's either placed in a glass, crystal, or jeweled coffin by her companions, or else she just lies where she fell in the castle where she now lives alone, to be found later by the prince when he ventures inside, a la Sleeping Beauty.

*The villainess is sometimes executed by the prince in the end, but in other versions she goes unpunished.

**Two versions, The Beautiful Anna and Maruzzedda, continue after the heroine revives with second halves that recall certain Sleeping Beauty tales. The prince marries the heroine and fathers two or three children with her, but he keeps his marriage and children a secret from his cruel, possessive mother. Eventually, the mother finds out and tries to have the heroine and children killed, but in the end her schemes are thwarted and she's put to death instead.

Coming up next: versions from Greece, Albania, and Turkey.

@ariel-seagull-wings, @adarkrainbow, @themousefromfantasyland

#snow white#fairy tale#variations#sleeping beauties: sleeping beauty and snow white tales from around the world#heidi anne heiner#france#italy

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below the cut I have made a list of each English and British monarch, the age of their mothers at their births, and which number pregnancy they were the result of. Particularly before the early modern era, the perception of Queens and childbearing is quite skewed, which prompted me to make this list. I started with William I as the Anglo-Saxon kings didn’t have enough information for this list.

House of Normandy

William I (b. c.1028)

Son of Herleva (b. c.1003)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

William II (b. c.1057/60)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Third pregnancy at minimum, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 26/29 at birth.

Henry I (b. c.1068)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Fourth pregnancy at minimum, more likely eighth or ninth, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 37 at birth.

Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

Daughter of Matilda of Scotland (b. c.1080)

First pregnancy, possibly second.

Approx age 22 at birth.

Stephen (b. c.1092/6)

Son of Adela of Normandy (b. c.1067)

Fifth pregnancy, although exact birth order is uncertain.

Approx age 25/29 at birth.

Henry II (b. 5 Mar 1133)

Son of Empress Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

First pregnancy.

Age 31 at birth.

Richard I (b. 8 Sep 1157)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 35 at birth.

John (b. 24 Dec 1166)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Tenth pregnancy.

Approx age 44 at birth.

House of Plantagenet

Henry III (b. 1 Oct 1207)

Son of Isabella of Angoulême (b. c.1186/88)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 19/21 at birth.

Edward I (b. 17 Jun 1239)

Son of Eleanor of Provence (b. c.1223)

First pregnancy.

Age approx 16 at birth.

Edward II (b. 25 Apr 1284)

Son of Eleanor of Castile (b. c.1241)

Sixteenth pregnancy.

Approx age 43 at birth.

Edward III (b. 13 Nov 1312)

Son of Isabella of France (b. c.1295)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 17 at birth.

Richard II (b. 6 Jan 1367)

Son of Joan of Kent (b. 29 Sep 1326/7)

Seventh pregnancy.

Approx age 39/40 at birth.

House of Lancaster

Henry IV (b. c.Apr 1367)

Son of Blanche of Lancaster (b. 25 Mar 1342)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

Henry V (b. 16 Sep 1386)

Son of Mary de Bohun (b. c.1369/70)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 16/17 at birth.

Henry VI (b. 6 Dec 1421)

Son of Catherine of Valois (b. 27 Oct 1401)

First pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

House of York

Edward IV (b. 28 Apr 1442)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Third pregnancy.

Age 26 at birth.

Edward V (b. 2 Nov 1470)

Son of Elizabeth Woodville (b. c.1437)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 33 at birth.

Richard III (b. 2 Oct 1452)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Eleventh pregnancy.

Age 37 at birth.

House of Tudor

Henry VII (b. 28 Jan 1457)

Son of Margaret Beaufort (b. 31 May 1443)

First pregnancy.

Age 13 at birth.

Henry VIII (b. 28 Jun 1491)

Son of Elizabeth of York (b. 11 Feb 1466)

Third pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Edward VI (b. 12 Oct 1537)

Son of Jane Seymour (b. c.1509)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 28 at birth.

Jane (b. c.1537)

Daughter of Frances Brandon (b. 16 Jul 1517)

Third pregnancy.

Approx age 20 at birth.

Mary I (b. 18 Feb 1516)

Daughter of Catherine of Aragon (b. 16 Dec 1485)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

Elizabeth I (b. 7 Sep 1533)

Daughter of Anne Boleyn (b. c.1501/7)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 26/32 at birth.

House of Stuart

James I (b. 19 Jun 1566)

Son of Mary I of Scotland (b. 8 Dec 1542)

First pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

Charles I (b. 19 Nov 1600)

Son of Anne of Denmark (b. 12 Dec 1574)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles II (b. 29 May 1630)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

James II (14 Oct 1633)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

William III (b. 4 Nov 1650)

Son of Mary, Princess Royal (b. 4 Nov 1631)

Second pregnancy.

Age 19 at birth.

Mary II (b. 30 Apr 1662)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Second pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Anne (b. 6 Feb 1665)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

House of Hanover

George I (b. 28 May 1660)

Son of Sophia of the Palatinate (b. 14 Oct 1630)

First pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

George II (b. 9 Nov 1683)

Son of Sophia Dorothea of Celle (b. 15 Sep 1666)

First pregnancy.

Age 17 at birth.

George III (b. 4 Jun 1738)

Son of Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (b. 30 Nov 1719)

Second pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

George IV (b. 12 Aug 1762)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

First pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

William IV (b. 21 Aug 1765)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

Third pregnancy.

Age 21 at birth.

Victoria (b. 24 May 1819)

Daughter of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafield (b. 17 Aug 1786)

Third pregnancy.

Age 32 at birth.

Edward VII (b. 9 Nov 1841)

Daughter of Victoria of the United Kingdom (b. 24 May 1819)

Second pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

House of Windsor

George V (b. 3 Jun 1865)

Son of Alexandra of Denmark (b. 1 Dec 1844)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

Edward VIII (b. 23 Jun 1894)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

First pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

George VI (b. 14 Dec 1895)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

Second pregnancy.

Age 28 at birth.

Elizabeth II (b. 21 Apr 1926)

Daughter of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (b. 4 Aug 1900)

First pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles III (b. 14 Nov 1948)

Son of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom (b. 21 Apr 1926)

First pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

City of Ladies: the game

This post is based on a discussion with @lilias42. The idea was to imagine what an all-women Civilization-like game would look like. Would that be even possible?

This was done for fun, my choice of leaders is in no way a political statement. My goal is to showcase amazing historical ladies. I couldn't include everyone, so some choices were made. Let's go!

Angola: Njinga Mbande

Arabia: Samsi/Al-Khayzuran

Byzantine Empire: Irene of Athens/Theodora the Armenian/Theodora Porphyrogenita/Eudokia Makrembolitissa/Anna Dalassene

Carthage: Elissa-Dido

China: Fu Hao/Queen Dowager Xuan/Wu Zetian/Empress Liu

Celts: Boudica/Cartimandua

Denmark: Margaret I of Denamrk

Egypt: Merneith/Ahhotep I/Hatshepsut

England: Seaxburh of Wessex/Æthelflæd of Mercia/Empress Matilda/Eleanor of Aquitaine/ Elizabeth I

France: Blanche of Castile/ Emma of France/Brunehilda/Fredegund/Anne of France

Georgia: Tamar of Georgia

Germany: Theophanu Skleraina/ Matilda of Quedlinburg

Greece: Laskarina Bouboulina

Inca: Mama Huaco/Chañan Cori Coca

India: Rani Lakshmibai/Rudrama Devi/Didda of Kashmir/Ahilyabai Holkar

Italy: Matilda of Tuscany/Joanna I of Naples/Caterina Sforza/Lucrezia Borgia

Japan: Himiko/Empress Suiko/Empress Jito/Hojo Masako

Korea: Seondeok/Jindeok/Empress Myeongseong

Macedonia: Olympias/Eurydice I of Macedon

Maya: Lady K'abel/Wak Chanil Ajaw/ Lady K’awiil Ajaw

Mongolia: Sorghaghtani Beki/Mandukhai Khatun

Nigeria: Amina of Zaria

Nubia: Amanirenas/Amanitore

Ottoman Empire: Hürrem Sultan/Kösem Sultan

Persia/Iran: Atossa/Boran/Qutlugh Turkhan

Poland: Jadwiga of Poland

Roman Empire: Agrippina the Elder/Julia Domna

Russia: Catherine the Great/Elizabeth of Russia

Scythians/Sarmatians: Tomyris/Sparethra/Amage/Zarinaia

Senegal: Ndaté Yalla Mbodj

South Africa: Mmanthatisi

Spain: Urraca of León and Castile/Isabella I of Castile

United States of America: Harriet Tubman

+indigenous nations and their leaders such as : The Lady of Cofitachequi/ Weetamoo (Wampanoag)/Nonhelema (Shawnee) / Bíawacheeitchish (Apsáalooke)/Pretty Nose (Arapaho)

Vietnam: The Trưng sisters

Yemen: Arwa al-Sulayhi/Asma bint Shihab

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The attraction of Eleanor of Aquitaine to post-medieval historians, novelists and artists is obvious. Heiress in her own right to Aquitaine, one of the wealthiest fiefs in Europe, she became in turn queen of France by marriage to Louis VII (1137–52) and of England by marriage to Henry II (1154–89). She was the mother of two of England’s most celebrated (or notorious) kings, Richard I and John, and played an important role in the politics of both their reigns. She was a powerful woman in an age assumed (not entirely correctly) to be dominated by men. She was associated with some of the great events and movements of her age: the crusades (she participated in the Second Crusade, and organized the ransom payments to free Richard I from the imprisonment that he suffered returning from the Third); the development of vernacular literature and the idea of courtly love (as granddaughter of the ‘first troubadour’ William IX of Aquitaine, she was also a patron of some of the earliest Arthurian literature in French, and featured in one of the foundational works on courtly love); and the Plantagenet–Capetian conflict that foreshadowed centuries of struggle between England and France (her divorce from Louis VII and marriage to Henry II took Aquitaine out of the Capetian orbit, and created the ‘Angevin Empire’). She enjoyed a long life (she was about eighty years old at the time of her death in 1204) and produced nine children who lived to adulthood. The marriages of her off spring linked her (and the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties) to the royal houses of Castile, Sicily and Navarre, and to the great noble lines of Brittany and Blois-Champagne in France and the Welfs in Germany. A sense of both the geographical and temporal extent of Eleanor’s world can be appreciated when we consider an example from the crusades. Eleanor accompanied her husband Louis VII on the Second Crusade in 1147–9; when Louis IX went on crusade over a hundred years later, he left France in the care of Blanche of Castile, a Spanish princess and Eleanor’s granddaughter, whose marriage to Louis’s father had been arranged by Eleanor. Just this single example shows her direct influence spanning a century, two crusades and three kingdoms.

— Michael R. Evans, Inventing Eleanor: The Medieval and Post-Medieval Image of Eleanor of Aquitaine

#slay#eleanor of aquitaine#historicwomendaily#english history#french history#12th century#women in history#richard I#king John#Henry II#angevins

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'Art et la mode, no. 31, vol. 15, 4 août 1894, Paris. Toilettes pour garden-parties, croquet, etc. Dessin de G. de Billy. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Robe de faille bleu pâle, voilée de tulle brodé ivoire; la blouse large est serrée à la taille par des plis fins; ceinture de velours fermée par des choux. Manches larges avec nœuds sur les épaules; manches très drapées sur un transparent bleu pâle, serrées au-dessus du coude par un bracelet de velours noir. Capeline Louis XVI. en dentelle, nœud de taffetas bleu, aigrette noire.

Pale blue faille dress, veiled with ivory embroidered tulle; the wide blouse is tightened at the waist by fine pleats; velvet belt closed by choux. Wide sleeves with bows on the shoulders; very draped sleeves on a pale blue transparent, tightened above the elbow by a black velvet bracelet. Louis XVI capeline. in lace, blue taffeta bow, black aigrette.

—

Robe en satin feuille de rose, genre princesse, avec plis dans le dos, retenus par une ceinture et des choux de satin; ruban remontant dans le dos sur une pèlerine de batiste brodée; manches courtes, gants blancs.

Princess-style rose-leaf satin dress with pleats in the back, held by a belt and satin puffs; ribbon running up the back on an embroidered batiste cape; short sleeves, white gloves.

—

Robe en mousseline ou batiste rousse sur transparent; garniture de point à l’aiguille; ceinture écharpe, en soie molle effilée dans le bas; grosse touffe de roses reine à la taille; devant du corsage coulissé; manches garnies d'entre-deux. Capeline paille de riz, garnie de marguerites, de rubans et de plumes.

Dress in russet muslin or batiste on transparent; needlepoint trim; scarf belt, in soft silk tapered at the bottom; large tuft of queen roses at the waist; front of the bodice drawn; sleeves trimmed with entre-deux. Rice straw wide-brimmed hat, trimmed with daisies, ribbons and feathers.

—

Robe en popeline soie crème, avec broderie Pompadour, en soie de teintes vives, formant des guirlandes; corsage de gaze de soie bleu pâle, garnie d’entre-deux en biais; col formant berthe coquillée en popeline de soie crème; nœud de velours noir. Chapeau en paille fantaisie, avec boucle, nœud de soie Louis XV, et aigrette blanche et noire

Cream silk poplin dress, with Pompadour embroidery, in brightly colored silk, forming garlands; pale blue silk gauze bodice, trimmed with biased entre-deux; collar forming a shell berthe in cream silk poplin; black velvet bow. Fancy straw hat, with buckle, Louis XV silk bow, and white and black aigrette

—

Corsage pour robe de tennis, en serge piquée ou drap blanc, plastron découpé, fermé par des boutons; pinces ouvertes, formant corselet, retenant les côtés du corsage qui ne sont pas ajustés. Manches larges, poignets ajustés.

Bodice for tennis dress, in pique serge or white cloth, cut-out plastron, closed with buttons; open darts, forming a corset, holding the sides of the bodice which are not fitted. Wide sleeves, fitted cuffs.

#L'Art et la mode#19th century#1890s#1894#on this day#August 4#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#description#bibliothèque nationale de france#dress#gigot#collar#Modèles de chez#G. de Billy

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women’s History Meme || Sibling Relationships (1/5) ↬ Berenguela, reina de Léon y de Castilla and Blanca de Castilla, reine de France

Queen Berenguela of Castile (1180–1246) was, in her lifetime and for some time thereafter, a dominant figure on the political landscape of the kingdoms of Castile and Leon. She typified the medieval elite woman whose ordained role in life was to be a wife and mother. The political circumstances of her native Castile, however, complicated and even enhanced Berenguela’s reproductive responsibilities. As the eldest daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile and his wife Leonor of England, Berenguela was at different points in her young life the presumed heir to the throne. The Castilians adhered to the Visigothic principle of partible inheritance. Although favoring sons, this principle meant that daughters had a claim to inheritance. Therefore, it was possible for a woman to inherit the throne when a male heir was lacking as had happened with Alfonso VI’s daughter Urraca in 1109 and with Berenguela in 1217. Berenguela’s awareness of and concern for her own lineage derived not only from a strong, involved identification with her natal family, based on her position as her father’s daughter, but also from her awareness of her own self as an element of that lineage. Her experiences and activities can be usefully contextualized by those of her numerous and important sisters, especially Urraca, Blanche, Leonor, and Constanza. They show ways in which Berenguela was like other elite women; indeed, her life could have turned out very much like one of theirs. Despite their individual circumstances, together they help demonstrate ways in which Berenguela was and was not alone in her experiences of family, marriage, motherhood, religion, and, above all, gender. Furthermore, the sisters were key elements of Berenguela’s family; throughout their lives, they remained in contact, if only for seemingly political reasons at times. Family visits, the fostering of children, and prayers for the dead suggest affective bonds as well as a deep sensibility of filial and sisterly piety among the members of this family. Berenguela’s sister Blanca (1188–1252) is better known as Blanche of Castile, queen of France, one of the most famous women of the Middle Ages. From the time of her marriage to the French heir Louis, Blanche was destined for significance, even if only as another female link in the seemingly miraculous chain of male inheritance that had secured the Capetian throne for generations. Three years after Blanche’s husband Louis became king, he was dead, and Blanche became regent both for her young son, Louis IX, and for the kingdom of France. Blanche became queen of France at a time when the institution of queenship seems to have undergone a shift, becoming increasingly relegated to the private, domestic world of the queen’s own household; at the very least, there is a change in the way documentation presented the queen’s activities at court. Although Blanche’s own political experiences were particular to her Capetian context, examining the several parallels between her experiences and those of her sister Berenguela points to certain consistencies in thirteenth-century royal motherhood and queenship. — Berenguela of Castile (1180–1246) and Political Women in the High Middle Ages by Miriam Shadis [old version]

#women's history meme#berengaria of castile#blanche of castile#house of ivrea#house of capet#medieval#spanish history#french history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Berenguela and Blanche of Castile

Daughters of Alfonso VIII of Castile and Eleanor of England, Berenguela maintained strong connections with her sister Blanche, Queen of France. Their letters are in Latin. Latin was still, at the beginning of the 13th century, the language of writing, while French and Castilian became the languages commonly spoken, even at court. Berenguela and Blanche were well-educated, competent and forceful like their formidable grandmother Eleanor of Aquitaine.

The two sisters will also lead a parallel existence, each exerting, in their own country, a comparable influence. Much like her younger sister Blanche in France, Berenguela presents an interesting case of co-rulership with her son in Castile. Furthermore, both have ties with warfare and played determinant roles in the success of military campaigns as well as access to – and maintenance of – the throne.

Berenguela and Blanche directed a great deal of their personal energy into assuring that all of their children were appropriately married. It was Blanche who suggested sending Joan of Ponthieu as a bride for her nephew Fernando after his first wife's death. Berenguela and Blanche became the mothers of fighting saints King Fernando III and King Louis IX.

In the Archives Nationales de France are nine letters written to King Louis VIII and his wife Blanche of Castile, during Louis’s brief reign from 1223 to 1226. These letters informed Louis VIII that Alfonso VIII of Castile had intended his throne to pass to a son of Louis and Blanche, if his own son Enrique died without heirs. Louis VIII should therefore immediately send his son to Castile, where his correspondents—the scions of several major Castilian noble houses—would take up arms to set him on the throne and overthrow the “foreigner” (alienus) who was in power. The most prominent of these Castilian magnates were Rodrigo Díaz de Cameros and Gonzalo Pérez de Molina. This conspiracy was an explicit attempt to dispose of the current Castilian monarchy and replace it with a new configuration of rulers. It was therefore a far more serious threat than either Rodrigo Díaz’s or Gonzalo Pérez’s earlier revolts had been. And it was aimed squarely at the legitimacy of the reigning monarchs.

The letters’ most perplexing feature is the suggestion that Blanche’s claim to the Castilian throne superseded Berenguela’s. Some historians have even taken this as evidence that Blanche was the elder sister, though that claim is patently false. Yet the plot to overthrow Fernando III was first of all an attempt to unseat Berenguela. It was through her that Fernando III claimed hereditary right and legitimate descent from Alfonso VIII. To say that Alfonso VIII had excluded Berenguela from the succession, and to describe Fernando as a “foreigner,” was to reject the Castilian identity that Berenguela had tried to reclaim during her ten years as a solitary queen in her father’s court, and that she had negotiated with varying success during her regency and the subsequent wars. It was to define her not as the daughter and sister of the latest kings of Castile, but as the cast-off wife of the king of León.

To be sure, Blanche and her sons were at least as French as Berenguela and Fernando III were Leonese. But the rebels were apparently willing to overlook this quibble; their appeal was directed as much to Louis VIII as to his queen. Besides, the threat of union with France was diminished by the fact that Blanche and Louis VIII had no fewer than five living sons at the time that they ruled France. The rebels never insisted that the son sent to them should be Louis VIII’s firstborn, and a younger brother’s accession in Castile considerably reduced the risk of union between the crowns. All five French princes were underage, but so much the better; the minorities of Alfonso VIII and Enrique I had proved how much power nobles could gain in a regency. Louis VIII was sufficiently intrigued by the rebels’ offer to have asked them for proof of their promised support. His wife, however, was likely to be less sympathetic. A combination of Blanche’s unwillingness to contribute to her older sister’s overthrow and Fernando III’s military successes after 1224 probably quashed the plot.

Sources:

JANNA BIANCHINI,THE QUEEN'S HAND: POWER AND AUTHORITY IN THE REIGN OF BERENGUELA OF CASTILE

Regine Pernoud, La Reine Blanche

#women in history#berenguela de castilla#berengaria of castile#blanca de castilla#blanche of castile#louis viii#fernando iii#louis ix#alfonso viii#eleanor of england#eleanor of aquitaine#french history#spanish history

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you see a similarity between Margery Tyrell (as well as Elinor Tyrell, Megga Tyrell, and Alla Tyrell) being put on trail and the trail of the daughter's in law of King Philip the Fair of France (specifically as described in The Accursed Kings), I was reading the Iron King a few weeks ago and it made me wonder if there was a connection as GRRM is a fan of the The Accursed Kings.

Me, think about a connection between ASOIAF and The Accursed Kings? Now when have I ever done that before?

(It me, it always me. Also long, more under the cut.)

Absolutely, I 100% believe that GRRM partially (emphasis on partially) based the supposed love affairs of Margaery and her cousins on the Tour de Nesle Affair as depicted in The Accursed Kings - specifically the first novel of the series, The Iron King. To very briefly summarize, the Tour de Nesle affair centers on the three daughters-in-law of King Philip IV of France: Marguerite of Burgundy, wife of Philip’s eldest son, Louis (and Queen of Navarre, since Louis is King of Navarre in his own right); Marguerite’s cousin Jeanne of Burgundy, wife of the king’s second son, Philip; and Jeanne’s sister (and, naturally, Marguerite’s cousin) Blanche, wife of the king’s third son, Charles. Marguerite and Blanche engage in extramarital sexual affairs with two courtiers, the brothers Philippe and Gautier d’Aunay, with Jeanne acting as facilitator and messenger for their trysts; the affair takes its name from the tower of the Hôtel-de-Nesle, the manor of the King of Navarre, where Marguerite and Blanche entertain their lovers. The affair is discovered by another French prince, Robert of Artois, and he and Philip IV’s daughter, Isabella, engineer a scheme to trap the princesses and expose them. Marguerite, Blanche, and Jeanne are subsequently caught and found guilty, the former two of adultery, the latter of aiding and abetting them; Marguerite and Blanche are imprisoned (the former until she is murdered, the latter until she dies, prematurely young and apparently insane), while Jeanne is likewise initially imprisoned but eventually freed by and reunited with her husband.

With respect to parallels between this story and the plot of AFFC, the Tour de Nesle affair and the affair Cersei invents for Margaery both involve several interrelated royal (or semi-royal) ladies. I mentioned above the princesses in The Iron King, who are called the “Princesses of Burgundy”: Marguerite is the daughter of the Duke of Burgundy, while her cousins Jeanne and Blanche are referred to as the “sisters of Burgundy”, daughters of the late Count of Burgundy. (Yes, the Duchy of Burgundy and County of Burgundy were at this time two separate political entities despite sharing a name). Likewise, the sexual scandal dreamed up by Cersei centers on four Tyrell girls at court, with one a queen: Queen Margaery, of course and three of her cousins, Megga, Elinor, and Alla. None of the Tyrell girls are sisters to any of the others, but all four are part of an extended Tyrell family, grouped together as “Tyrells” much as the three princesses of The Iron King are counted together by Robert of Artois as part of the “family of Burgundy”. In turn, just as Robert of Artois seeks to reveal the scandal specifically so that “[t]he whole family of Burgundy will be plunged up to the neck in the midden … [and] their inheritance will no longer be within reach of the Crown” - leaving that disputed inheritance open to Robert himself - so Cersei, furious at being “awash in roses”, dreams of framing Margaery for a crime of treason so serious that “even her own lord father must condemn her, or her shame becomes his own”.

Moreover, the parallel between these plots in The Iron King and AFFC is strengthened by the identities of the respective plotters. As I noted, one of the two chief architects of the plot against the princesses of Burgundy is Queen Isabella - daughter of King Philip IV of France, sister-in-law to the three princesses, and Queen of England as the wife of King Edward II. Just as Cersei is considered one of the most beautiful women in the Seven Kingdoms, inheriting the golden good looks of any number of Lannister antecedents, Isabella is often compared to her famously handsome father, Philip the Fair, sharing what Druon calls the king’s “legendary personal beauty”; a courtier of her father’s, Hughes de Bouville, even goes on to compliment Isabella in a later novel, The She-Wolf of France, by saying that Isabella had inherited “all [King Philip’s] beauty which was so impervious to time”. Yet The Iron King opens on Isabella by calling her “the loveless queen”, and it’s a description as fitting to Cersei as it is to the daughter of Philip IV. Just as Isabella is trapped in a miserable marriage to Edward II, so Cersei was trapped in a terrible marriage to King Robert Baratheon - marriages made by their respective fathers, for the political gains of their paternal families. Indeed, King Philip’s retort to Isabella’s complaints about her bad treatment at the hands of her husband - “I did not marry you to a man … but to a King. I did not sacrifice you by mistake” - seems like the sort of reply Tywin would have given to Cersei, having chosen to make his daughter queen and secure a future royal grandson despite privately dismissing Robert as a stupid oaf (to say nothing of Robert's years of abusing Cersei).

Likewise, both queens seek solace in their eldest sons, as well as their birth dynasties. Isabella is first shown approving that her baby son Edward’s first word was “want”, which Isabella calls “the speech of a king”; she also teaches her son that “he belongs to France as much as to England” and insists that he “get accustomed to the names of his relatives” and learn “that his grandfather, Philip the Fair, is King of France”. Isabella also surrounds herself with reminders of her French past: The Iron King opens with Isabella listening to a French poem, her most trusted lady-in-waiting is the French Jeanne de Joinville, and in a later novel, The She-Wolf of France, Isabella loses to her husband’s favorite a book of poetry by Marie of France. For her part, Cersei has made sure - or at least tried to make sure - that Joffrey was raised as a Lannister with no love for his Baratheon “father”; indeed, Cersei even likes to think of conceiving Joffrey with Jaime as an act of revenge against Robert while trapped at the home of Robert’s maternal family. Joffrey’s surcoat when he duels Robb at Winterfell shows the Lannister lion equal to the Baratheon stag, imagery he later makes his official standard when he becomes king, and he famously has in the first book a sword he proudly calls Lion’s Tooth; too, when he is married, the Lannister banners are displayed as equal to the Baratheon and Tyrell banners, underlining the Lannister importance in Joffrey’s reign.

Too, neither queen has much love for the eventual objects of their respective plotting. When Robert of Artois informs Isabella that the princesses of Burgundy “hate you”, Isabella replies that “[t]hough I don’t know why, it is true that as far as I am concerned, I never liked them from the start”; Robert then adds his opinion, that Isabella “didn’t like them because they’re false, because they think of nothing but pleasure and have no sense of duty”. Indeed, Isabella’s longstanding dislike and distrust of her sisters-in-law seems reflected in her suspicions, apparently established before the beginning of The Iron King, that the princesses were already deceiving their husbands with extramarital lovers, seemingly heightened by the contrast to her own faithful (for her part) but loveless marriage - Isabella later tells Robert that “when I think of what I am denying myself, what I am giving up, then I know how lucky they are to have husbands who love them”, declaring “[t]hey must be punished, properly punished!”. Cersei’s distrust of Margaery, of course, can hardly be overstated, though in her case the origins of her hatred stem not from Margaery herself but rather Cersei’s paranoia about her, Cersei’s, own prophesied downfall at the hands of a younger and more beautiful queen. Convinced - probably at her ultimate cost - that her son’s (or sons’) eventual wife would fulfill the prophecy Maggy gave so many years prior, Cersei was predisposed to dislike, distrust, and deeply fear such a woman from the first

So both queens set out to denounce and bring down their royal in-laws through the revelation of a sexual scandal - the bombshell news that a queen and her aristocratic cousins have taken lovers in the persons of a few highborn courtiers. Both plots begin at their outset with the queens appointing spies in the households of the targets of the plots. Robert of Artois advises Isabella to request one of his allies be placed in Marguerite’s household as what he terms “a spy within the walls” - a successful move for Robert and Isabella's conspiracy, as not only does Marguerite (correctly) suspect Madame de Comminges for “always trailing about in her widow’s weeds”, but Robert also reveals that “[s]ince entering Marguerite’s service, Madame de Comminges sent him a report every day”. Cersei herself recruits Taena Merryweather from Margaery’s own household, blithely confirming Jaime’s suspicion that “[s]he’s informing on you to the little queen by saying that “Taena tells me everything Maid Margaery is doing”. Taena, for her part, tells Cersei what Cersei wants to hear, often dropping sexually suggestive hints supposedly about Margaery and her court, which encourage Cersei in her plot against Margaery.

Additionally, each queen faces the difficulty in singling out the rival queen in question given the presence of those rivals’ respective ladies. Robert of Artois complains that the princesses of Burgundy are “[c]lever wenches” because while Jeanne or Blanche often go to “pray” with Marguerite at the Tour de Nesle, each acts as an alibi for the other; as Robert concludes, “[o]ne woman at fault finds it difficult to defend herself”, but “[t]hree wicked harlots are a fortress”. Indeed, Taena Merryweather borrows almost the exact same castellated metaphor from Robert, claiming that Margaery’s “women are her castle walls”, as “[w]henever men are about, her septa will be with her, or her cousins”. This commentary from Taena inspires Cersei to ponder whether “[Margaery’s] ladies are part of it as well … [sic] not all of them, perhaps, but some” and then manipulate the confession of the Blue Bard to implicate Elinor, Megga, and Alla in the invented affair.

So in both cases, the groups of royal ladies are accused of fornication, with one lady from each excepted for a charge of what we might call criminal knowledge instead. In the case of the princesses of Burgundy, it is Jeanne who is deemed “guilty of complicity and culpable complacence”, while in the case of the Tyrells it is young Alla who is “charged with witnessing their shame [i.e. the supposed sexual relationships of Megga, Elinor, and Margaery] and helping them conceal it”. The distinction in charges notwithstanding, all the ladies are thereafter imprisoned, with both the Burgundy princesses and the Tyrell ladies stripped of their finery: at their judgment, the princesses of Burgundy kneel before the king “shaven and clothed in rough fustian” (so humbled that Jeanne and Blanche’s mother mistakes them for “three young monks”), and when Cersei visits the imprisoned Margaery, the young queen is dressed in “the roughspun shift of a novice sister”, with “[h]er locks … all a tangle”.

(It’s probably going too far to suggest that the planned roles for two courtier brothers in Cersei’s plot echoes the involvement of the d’Aunay brothers in the Tour de Nesle affair. After all, only Osney of the three Kettleblacks was supposed to have had sex with Margaery, and only Osney did have sex with Cersei, whatever Cersei would later claim to the High Septon.)

(I would be amused if GRRM named Margaery after Marguerite of Burgundy, knowing perhaps he would use her in an Accursed Kings-like plot in the future. However, I’m not saying this was necessarily or even likely the case: Margaery had been named since AGOT, after all long before the writing and publication of AFFC, and while GRRM’s affection for Maurice Druon and The Accursed Kings predates ASOIAF, there is no evidence that he planned this sort of parallel all the way back in 1996. The similarity of names may be simply an amusing coincidence, or even a retroactive realization by GRRM that he could use a similarly named character to star in a plot directly inspired by Marguerite of Burgundy’s story.)

Now, does this mean GRRM limited himself to The Iron King in creating this plot point for AFFC? Absolutely not, I would say. Indeed, I think it is very clear that GRRM also looked to the popular conception of the downfall of, and all but certainly false accusations leveled against, Anne Boleyn for further inspiration. Here, as in the popular imagination of Anne’s undoing, is a queen accused of sexual affairs with several male courtiers, who are imprisoned along with her (though note that according); here, as in the trial of Anne Boleyn, is a singer, supposedly among those accused lovers, tortured into a presumably false confession (and being the only accused lover to confess); here, as with Anne and George Boleyn, is a charge of incest against a queen and her brother, so obviously ludicrous in both cases that no contemporary takes it seriously; here, as with the arrests and subsequent release of Thomas Wyatt and Richard Page, are two courtiers seemingly accused of the same crime, but expected to be freed in order to demonstrate the guilt of the others. It’s an obvious but important point that GRRM does not need to borrow only to one point of inspiration, fictional or historical (or, rather, what he imagines as historical), for any given narrative he wants to write. Drawing connections between The Iron King and the plot against Margaery and her cousins no more invalidates connections between that same plot and the popular conception of Anne Boleyn’s downfall than comparing, say, Baelor to Louis IX of France (including the latter’s depiction in The Accursed Kings) invalidates comparisons between Baelor and Henry VI of England.

This last point extends to Cersei herself as well. While I definitely believe GRRM borrowed elements from Isabella of France for Cersei, I have also argued, and still believe, that Cersei also shared elements of her character and story with Marguerite of Burgundy herself. Parallels between Cersei and Marguerite should not nullify or undermine parallels between Margaery and Marguerite (specifically in this context of affairs/supposed affairs), any more than parallels between, say, Edward IV of England and Robert Baratheon should nullify or undermine parallels between that same King Edward and Robb Stark (specifically in the context of a secret marriage with no apparent political benefit). GRRM is not required to neatly match one for one a character in his universe to a historical or fictional figure, nor would I think we as readers would want him to; it would be a pretty boring story if he simply copy pasted figures from extant works or history and swapped their names for those he created.

Plus, I think Margaery and her cousins are pretty likely to come out of their trials much better than the princesses of Burgundy did with theirs. Most obviously, as even the High Septon admitted, the case against the queen and her cousins is weak - as indeed it might be, given that Cersei invented the affair in the first place. Far from the d’Aunay boasting about their royal lovers by wearing the infamous purses given them by the princesses (and gifted to them by Queen Isabella, to catch the lovers with them), all of the supposed lovers of the Tyrell girls save the Blue Bard have denied the affair, and his testimony is denounced as “half-mad”. On a practical level, the High Septon surely knows the danger for him, and his position, of convicting Margaery, given that Osney reported on the crown of sparrows demanding Margaery’s release (news Cersei regards ruefully, since as she thinks “Margaery has been their little pet”). Add to that threat the presence of Mace at the head of his army, returned to the capital explicitly to see through his daughter’s trial, and the High Sparrow is playing with fire in truly trying to convict Margaery and her cousins.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The education of St. Louis.

#royaume de france#st louis#st louis ix#roi de france#vive le roi#blanche de castille#reine de france#vive la reine#capétiens#capetians#kingdom of france#saints#christianism#catholicism#queen mother

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love your blog so much! I love all the Claudia's info and the rare pics!

Do you know more about her sister Blanche? She looked sooo pretty!

Thank you so much! Delighted that you like my Tumblr and little by little I will upload more information and photos 😍

Blanche Cardinale:

She was born a year after Claudia, 1939 in La Goulette, Tunisia and is the second sister of 4 brothers; Claudia, Blanche, Bruno and Adriano.

Blanche accompanied her mother and her sister Claudia at the "The Most Beautiful Girl in Tunisia" beauty pageant to help with the preparations.

Although like her sister she did not participate in the contest, she Blanche came in second place.

/Blanche on the left and Claudia next/

She helped her sister Claudia to move her to Rome...

so that Claudia could play her first roles and Blanche sometimes made a small appearance like in this scene from the movie "Un Maledetto Imbroglio"

With beautiful blonde hair, white skin and bright blue eyes, one of her dreams was to be an actress (Quite the opposite of Claudia)

and Italian director Aldo Sinesio hired her for the movie "Tutto Il Bello Dell 'Uomo" based on mafia in 1962.

As the protagonist alongside Italian actor Dante Posani with whom she seems to have had a "romance".

The film is considered lost since there are no copies or the original tape.

After the film Blanche decided to dedicate herself to her other passion, turning it into her profession; She is a photographer at 23 years old.

Claudia was her first model and then she photographed Mylène Demongeot among other actors and actresses.

/Claudia Cardinale by Blanche Cardinale/

/Mylène Demongeot for Queen magazine in 1963/

She was also secretary to her sister Claudia, replacing Carolyn Pfeiffer (on the pic with Claudia on 8 1/2 behind scenes)

who sadly had to resign because she was going to live in France and at the same time would work as a secretary for Romy Schneider and Alain Delon who were working in Paris.

/Blanche and Claudia for an interview, 1964/

Blanche married the Italian director Mario Forges Davanzati and from this union she had 3 children: Luca, Simone and the only daughter Tiare.

Blanche sang "Piú Peggio di Cosi" for the film "Per amore… per magic" produced by her brother-in-law, the Italian director Franco Cristaldi, and included on the singer Gianni Morandi's album in 1967:

She later worked as a designer and costume designer in the late 1960s and then worked at the Armani emporium in Paris, France.

/Blanche with Claudia and Yasmin Aga Khan (Rita Hayworth's daughter) in "Circus World" behind scenes/

Blanche is currently 85 years old, I am not sure what country she currently lives in but whatever country she is in I know she is very happy!

"Blanche was the pretty one of the family, the complete opposite of me; Blonde hair, blue eyes, lighter skin… she was every director's dream! "

- Claudia Cardinale in 2017

Credits: 📷 Photos by Angelo Frontoni. 📷 Luce Archive.

#claudia cardinale#blanche cardinale#60s#actress#vintage#my gifs#quotes#1962#1966#ask me anything#ask#mylene demongeot#yasmin khan#rita hayworth#my gif#gif#carolyn pfeiffer

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A legend almost in her own lifetime"

Like her grandmother Eleanor of Aquitaine and her uncle Richard the Lionheart, Blanche became a legend almost in her own lifetime. For Philippe Mousquès, writing within her lifetime, she was a formidable presence: she was the wise queen, whose son loved her more deeply than any other son could love his mother, and obeyed her in all things. The Ménestrel of Reims wrote in 1262, a mere ten years after her death and long before the image of Blanche became caught up in attempts to declare her son a saint. The Ménestrel has several striking anecdotes featuring Blanche. He tells the story of Blanche blackmailing Philip Augustus into releasing monies to rescue Lord Louis's English campaign by threatening to pawn her children. He tells too the unforgettable story of Blanche disproving the slander that she had been made pregnant by Cardinal Romanus, by jumping on a table in full council and throwing off an enveloping mantle to reveal herself in nothing but a flimsy chemise. "Lords, look at me, all of you: someone has said that I am pregnant with a child", she challenges them, as she twirls on the table to show off her svelte figure. When she died, Matthew Paris called her the "Lady of the ladies of this world", and compared her to the Persian empress Semiramis. Matthew had developed into one of her most ardent admirers, and it is clear from the context that the highest praise is intended.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#queens of france#aliénor d'aquitaine#richard coeur de lion#philippe mousquès#matthew paris#philippe ii#philippe auguste#louis viii#cardinal romain de saint-ange#:))

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Now that the Histories Ficathon is over I'm making good on my threat/promise... please assign the Lancasterlings (and their spouses, if you want) a prehistoric creature to go alongside Thomasaurus Rex.

yes...haha yes! 😈

this got long so under the cut:

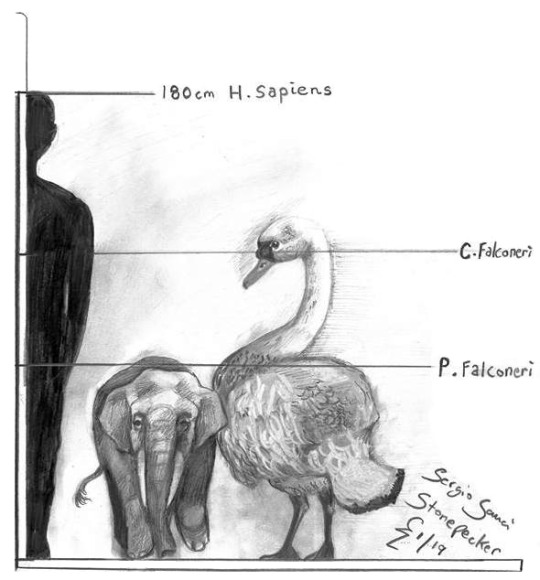

Henry V:

Okay hear me out- we keep keep the swan theme and connection to Mary and her family as strong, tight throughline also I love the idea of Hal beating up people aggressive-swan-style. But- hear me out- bigger. So I'm thinking the giant Pleistocene swan Cygnus falconeri. It's a beautiful morning in France, and you are a horrible swan.

Artist: Sergio Gauci

Given Henry VI may have gotten his panther badge from his mom, may I also propose for Catherine de Valois the Eurasian extinct giant cheetah species Acinonyx pardinensis?

Artist: Velizar Simeonovski

Thomas, Duke of Clarence:

Obviously a T. rex, but I'm gonna stick this bit in from Brusatte's The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs to show how perfect that choice is 🤌✨

I admittedly know very little about Margaret Holland, but I was kind of compelled by how her children from her first marriage were kept in her and Thomas' household...that and Margaret wanting her book of hours to prepare her to "always be redy to dye," reminds me of the oviraptorid fossil that died and was preserved in position of protecting its eggs. Something about that as a parallel to her being buried alongside both her husbands too....

Artist: Zhao Chuang

John, Duke of Bedford:

Maybe it's because he himself seemed constantly stressed and running around doing some sort of assignment, and in the plays it's sometimes played as if he dies from sheer exhaustion, but I kind of like the idea of a beardog like Ischyrocyon or Amphicyon. The beardogs were famously generalists in hunting and in both of the above genera, it's hypothesized they may have been persistence hunters.

youtube

Also voting for Anne of Burgundy as an alvarezsauroid like Mononykus or Shuvuuia, which have been compared to nocturnal avian hunters like owls 🤎🤍

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester:

So a guy having a pretty productive relationship to his family (not perfect, but pretty good compared to others I could name...) trying his best to be an actual protector of his relative's kid, having a lot of relationship drama, and also getting into spats with people reads as very ceratopsian to me lmao. To de-fang him a just a little, I'm going with Kosmoceratops. Those folded horns on the top edge of the frill and side-facing brow horns probably aren't going to help you that much at Agincourt, but I'm sure that pretty lady from Cobham thinks they're fire 👍

Artist: Lukas Panzarin

Speaking of: I like the idea of Eleanor of Cobham maybe being assigned with some sort of plesiosaur? Sort of bridging the siren to mermaid to modern creature of our mythical imagination Nessie pipeline :)

Artist: James Kuether

For Jacoba, Smilodon. They're smart and fierce so fitting. Also what she deserves ❤️🔥

Artist: Mehdi Nikbakhsh

Blanche:

Unfortunately I couldn't find a whole lot on her, but that sort of elusive energy kind of reminds me of Coelurus fragilis, a possible Jurassic relative of the tyrannosaurs, but not much is known about their evolution or ecology. That and it being a more gracile and swift-footed creature kind of has Blanche vibes to me 🤍

Artist: Nobu Tamura

Ludwig deserves nothing and gets nothing bye

Philippa, Queen of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway:

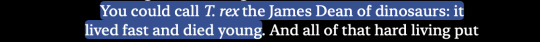

I know in the fic poor Philippa seems pretty freaked out by Thomasaurus' size, but I'm partial to her being a big death lizard too– maybe like those coming-of-age mermaid stories but she's...bigger and teeth-ier 😅. For a similar reason to seeing what Thomas would do at Baugé, I'd like to see Philippa defend Copenhagen as a Mosasaurus hoffmannii. Let's see the Hanseatic League try to get past THIS 🫡 min dronning 🫡

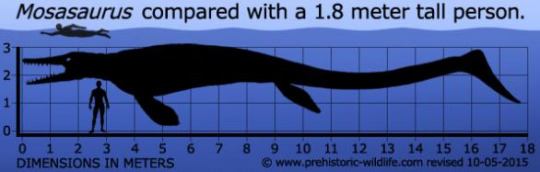

I like the idea of Erik also being associated with something aquatic though maybe not as intimidating as Philippa...maybe an early whale relative like Dorudon?

Artist: David Arruda Mourao

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugenie Servieres - Blanche of Castile freeing prisoners - 1818

oil on canvas, height: 141 cm (55.5 in) Edit this at Wikidata; width: 109 cm (42.9 in)

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Libourne, France

Blanche of Castile (Spanish: Blanca de Castilla; 4 March 1188 – 27 November 1252) was Queen of France by marriage to Louis VIII. She acted as regent twice during the reign of her son, Louis IX: during his minority from 1226 until 1234, and during his absence from 1248 until 1252.

A crowd of serfs of the officers of the chapter of Chastenay had been plunged into the prisons of this chapter for not having paid the size attached to their condition. The Regent, touched with compassion, at the complaints she received, asked the officers of the chapter to release them from prison on her bail; but she was refused and soon learned that a number of these unfortunate people were going to perish, either from hunger or from all the inconveniences they suffered in a place barely capable of containing them. Blanche, indignant, goes to the prisons of the chapter, where she orders the doors to be broken down, and with her scepter gives the first blow. This blow was so well seconded that in an instant the door fell to the ground. We then saw a multitude of men, women and children, with dying, pale and disfigured faces, who, throwing themselves at her feet, begged her to take them under her protection (His. of the Queens and Regents of France , volume I)

Eugénie Honorée Marguerite Servières, née Charen (1786 – 20 March 1855) was a French painter in the Troubadour style. She specialized in genre period paintings.

7 notes

·

View notes