#President Eisenshower

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Exodus

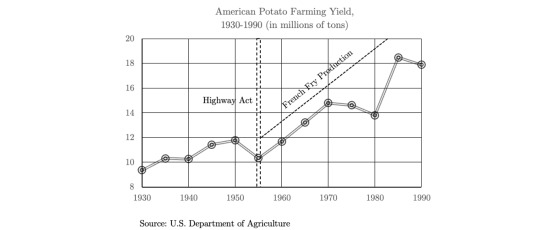

Consolidating fragmented supply chains through statecraft proved to be a potent jolt for enterprising industries in the 1910s. The success was replicated four decades later when the descendent of motorway expansion legislated the Interstate Highway System which became the crown jewel of President Dwight Eisenhower’s incumbency. Known as the Highway Act of 1956 it allocated $25b or the equivalent of $280b today for 41,000 miles of expressway over a decade by fronting 90 percent of costs shared with states. The asphalted ambition pared down travel times between coasts from upwards of two weeks by more than half before the close of the 1960s. A brisk five days of travel between New York to San Francisco had structural implications for the economy based on this civil engineering feat. Quite predictably Detroit automakers in particular were gifted a boom in annual sales by 48 percent between 1951 and 1965 as the change in road stock aroused the ubiquity of vehicles. Politics of mobility further reduced the friction of supply chains whilst simultaneously whetting the wanderlust of Americans as evidenced by the public capital’s intensity of use. After some stocktaking the return on investment approximated 20 percent for the economy due to the improvement in inbound and outbound logistics (Congressional Budget Office 1991).

America’s largest peacetime works program followed by the Panama Canal reimagined once more industrial development by carrying one-quarter of the country’s road traffic upon completion. Each dollar of cost apportioned to the superhighway yielded a six-fold return in productivity gains (Cox and Love 1998). Compared with rail and byways the Interstate saw roughly twenty-six times more traffic density in a testament to its speed and efficiency which changed America from a kaleidoscope of businesses into a single contiguous market. Any given lane services four thousand vehicles per hour in peak travel times so naturally such capacity elicited productivity growth in sectors reliant on transportation. Most lauded was how faster roads would optimize supply chains with the net effect of higher prosperity. Infrastructure spending of this species epitomized economist Robert Solow’s ideas on the mechanics of growth which hinges not so much on capital accumulation but productivity (1956). This nuanced exegesis intimates the number of factories on a company’s ledger is of little import compared with how efficiently they operate. Productivity matters more than capital intensity. America’s version of the Autobahn thus promised to strategically multiply growth rather than merely add to it by compressing time and space.

The Highway Act beyond its physical manifestation introduced industrywide savings as tractor-trailer costs declined by 17 percent translating into economies for consumers and their purchasing power. Americans saw their consumption rise commensurate with their dollars stretching further. When channeled into core business functions travel time reductions in the range of 60 percent were monetized to be worth $438b for Interstate users (Federal Highway Administration 1970). Companies revelled in this reality of transit costs no longer gnawing away at their margins in virtue of less outlays in fuel, wear and tear and labour hours. Rather than a passive investment this leviathan of a project in the postwar years brought about a windfall of wealth creation. A quarter of the nation’s productivity increase at the time resulted from the audacious 5 percent of GDP invested towards this single piece of infrastructure. The dividends were aplenty now that companies were poised to produce and distribute goods more swiftly which necessitated a hiring spree in keeping with the expansion of operations. Not only did Interstates provide a facelift to logistics but they indirectly became employment generators for a raft of industries downstream. Carmakers for instance grew by leaps and bounds by employing one out of six Americans (Sugrue 2012).

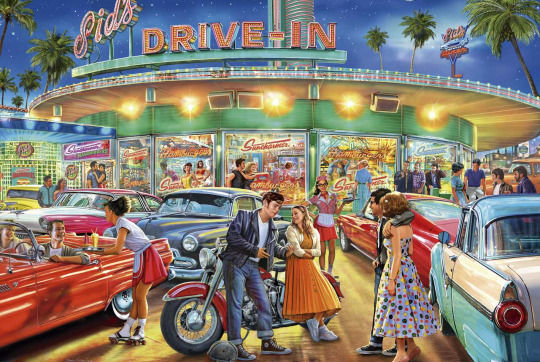

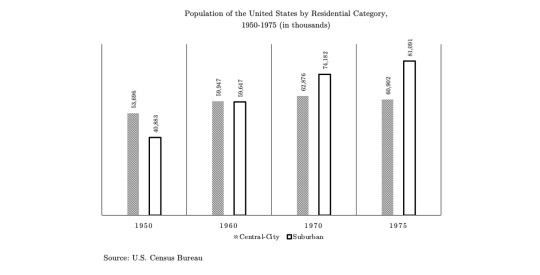

The golden age of infrastructure might have had its most profound effect on tertiary industries. One bellwether for the change afoot was the exodus towards the white-picketed suburbs that saw an increase in private and commercial real estate activity. By 1960 sixteen out of the largest twenty cities succumbed to significant population loss with a housing boom proliferating in their peripheries (Myers 1963). The cramped quarters of urban living became anathema to a growing-middle class whose love affair with backyard dimensions caused suburbs to grow by a factor of two from forty to eighty million between 1950 and 1975. President Eisenhower’s Interstates would personify the silhouette of modern America with cathedrals of capitalism in the form of shopping malls springing up next to these corridors. Culinary preferences were not spared either with drive-thru culture becoming a staple of the retail utopia which abounded in greenfield sites for developers. The centrifugal forces wrought by the Highway Act haemorrhaged demographics in cities towards these manicured enclaves as family formation in more verdant grounds appealed to WWII veterans. Suburbs invariably evolved into icons of middle-class aspiration around which scores of industries coalesced to profit from a migration spurred by Eisenhower.

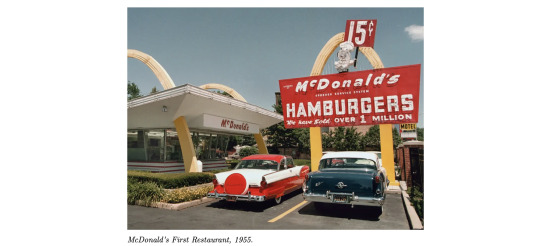

The industrial policy of the Highway Act did not operate in a vacuum instead beckoning a panoply of companies to service commuters and road trippers in new markets. Part of America’s mythology in the 1950s would be the surge in fast food eateries that popularized the hamburger and French fry between the likes of Dairy Queen, Burger King and McDonald’s. Highways were synonymous with the comfort food and its mass consumption could be read in the potato industry’s annual yield which reversed prior years of stagnation. Between 1961 and 1971 the franchise units adorned with the Golden Arches multiplied by 758 percent and even surpassed the United States Army as the largest dispenser of meals (Hackett 1976). Similarly the restaurant chain known as Kentucky Fried Chicken accounted for 6 percent of all broiler demand in America (Wilcox 1971: 24). It quickly came to pass that a franchise model disrupted the food industry’s traditional family-owned diner from drive-ins to drive-thrus wherein carhops would be bypassed. These establishments colonized the suburbs even to the point of oversaturating them as they jostled for marketshare amidst the halcyon years of suburbia. The fast-food industry’s rise to stardom was in no small part a corollary to how the Interstate transformed the gastronomy of American consumers.

0 notes

Text

Trump has proved he can read off a teleprompter but that doesn't make him presidential

Trump has proved he can read off a teleprompter but that doesn’t make him presidential

In 1954, four years after it was created by an American electrical engineer called Hubert Schlafly, Dwight Eisenshower became the first US president to make use of a teleprompter for a State of the Union address.

Since then, just about everyone who followed has done the same, and some with more grace than others. Barack Obama made it look utterly natural, whereas the pauses in George W Bush’s…

View On WordPress

0 notes