#Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Most Secret Plot Twist in Gaming History: Punished "Venom" Snake's True Identity Mystery in Metal Gear Solid V The Phantom Pain

youtube

The most secret plot twist in gaming history - Punished "Venom" Snake and Ricardo "Chico" Valenciano Libre being one and the same person in Metal Gear Solid V The Phantom Pain - was foreshadowed multiple times since (but not only...) Metal Gear Solid Peace Walker's Title Sequence (a Hideo Kojima game released in 2010 for the Sony PlayStation Portable originally planned to be titled "Metal Gear Solid 5: Peace Walker")

which shows this mirror breaking transition with two hidden butterflies (suggested play speed 0,25x) revealing - Chico Young volunteer in Snake's private army - the "Hombre Nuevo" chosen for Hideo Kojima's Metal Gear Solid V Experience as its new main protagonist

youtube

(which includes P.T. Silent Hills Concept Movie with the Chico's head appearance...)

youtube

that was, and still is, believed by most of the audience and its english language speaking vocal minority in particular (also known as the "Metal Gear community") to have died in the final helicopter crash cutscenes from Metal Gear Solid V Ground Zeroes showed in this video which was mirrored "for a special reason."

youtube

This crucial hint, hidden in plain sight, was secretly a direct reference left by the Metal Gear mastermind to be seen, and then revisited, only by those "good listeners" among his fans whose minds are still looking for the Truth behind the Hideo Kojima's Metal Gear Solid V Experience in the future MGSV games released years after such as it occurs in this very pivotal moment from MGSVTPP's Episode 46 Truth The Man Who Sold The World ending cutscene when the main protagonist punches the mirror "...for a S-Special reason."

I highly recommend to read the not flipped text printed down below in this Metal Gear Solid V Ground Zeroes' poster showing - Snake A former hero once known by the code name "Big Boss" - revealed during the Metal Gear Saga 25th Anniversary Party for the details...

The text "ƎЯƎH ꓘƆI��Ɔ" from Konami's Metal Gear 25th Anniversary Party Special Site was also flipped "for a special reason."

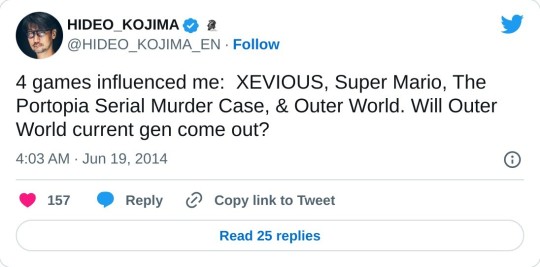

This crucial hint was also a tribute to Yuji Horii's Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken/The Portopia Serial Murder Case in which a butterfly is revealed to be a critical clue for the player trying to solve that mystery

which was one of the most influential games inspiring Hideo Kojima into starting his career as game designer

The original version for the NEC PC-6001 cassette tape data loader sound of Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken/The Portopia Serial Murder Case

youtube

was originally included in Metal Gear Solid V Ground Zeroes' "Classified Intel Data" (timestamp 1:01:50)

youtube

and Metal Gear Solid V The Phantom Pain's "Operation Intrude N313" cassette tapes as a clue to solve Punished "Venom" Snake's true identity mystery, the key to decipher the entire Metal Gear Solid V Experience's enigma

youtube

before being changed by the "Metal Gear Development Team" left in Konami after Kojima's departure from the company in October 9th 2015

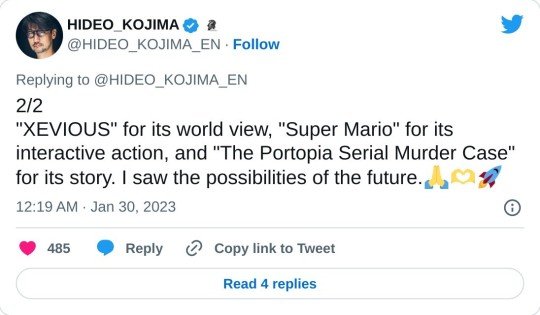

with the MSX version of the original Hideo Kojima's Metal Gear game (here displayed during Metal Gear Solid V Ground Zeroes boot camp held in Nasu on february 2014 in which the japanese game designer is "recreating a scene" from both his past and The Phantom Pain player's future...)

after being discovered by dataminers of the MGSVTPP pc version

in order to trying to keep hidden the most secret plot twist in gaming history before someone would have been able to find it...

...that someone was this online persona known by the username @ItalianJoe83 very long time ago (timestamp 1:41:50)

which social media activities including this video

youtube

weren’t, and are not, affiliated in any capacity with Konami Digital Entertainment like the spreading of this Google document

created and updated for years by Twitter user @HastatusAtratus

explaining in details all the issues still afflicting this Hideo Kojima's "social experiment" known as The Secret Nuclear Disarmament Event of Metal Gear Solid V The Phantom Pain...

...which wasn't even mentioned in this DidYouKnowGaming's video and its description box about how Konami is still hiding Metal Gear Solid V The Phantom Pain's Final Chapter from the entire playerbase since the game's release date...

youtube

...despite the fact I actually did asked to the author of this video @DrLavaYT (who asked me for my contribution after most of his video script was already finalized) to include @HastatusAtratus's username on top of the contributors list as he deserved but his name was nowhere to be seen and heard for some reason...

...and here's a now "Deleted User" Hung Horse's direct message reply to me on Discord in which he didn't just confirmed his awareness of this Google document existence but he also admitted to have took inspiration from Hastatus Atratus' monumental work into exposing Konami's agenda (way long before anybody else) for his group's activities...

...thus, everything else the audience is being shown and told in this DidYouKnowGaming's YouTube video outside from my contribution (which goes by timestamp 17:42 up to 18:26) should be considered as to being approved by/affiliated with Konami Digital Entertainment in official capacity before the final upload...

Note: this "Brain Structure" Episode #24 [ENGLISH] in which Hideo Kojima (voiced by Aki Saito) has a conversation with the Ricardo "Chico" Valenciano Libre's japanese voice actress Kikuko Inoue may also cause some "conflicts" of massive magnitude with the "good listener's" "internal timeline" starting at 35:22 up to 36:56 in particular "for a special reason."

Be aware of all this facts while you're looking for the Truth on the r/AHideoKojimaRuse subreddit...

..."Hombre"

youtube

#secret#plot twist#gaming#history#Punished “Venom” Snake#Ricardo “Chico” Valenciano Libre#metal gear solid v the phantom pain#metal gear solid v ground zeroes#metal gear solid peace walker#venom snake#Ricardo Valenciano Libre#punished snake#snake#mirror#butterflies#butterfly#a hideo kojima game#hideo kojima#metal gear#@ItalianJoe83#portopia renzoku satsujin jiken#the portopia serial murder case#A Hideo Kojima Ruse#metal gear solid v#metal gear solid 5#Chico#Metal Gear Solid V Experience#P.T. Concept Movie#P.T. Silent Hills#Hombre Nuevo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken November 29, 1985 // Family Computer

Nowadays, when someone says they play games "for the story," no one bats an eye. Gameplay purists might scoff, but games have become a storytelling medium like any other. In 1985, especially on consoles, that wasn't really the case. Most console games had only the vague outline of a story, and a lot of times it was just contained in a blurb in the manual. Then comes Portopia, a game where the gameplay is not shooting or jumping, but talking to people as you try to unravel a murder mystery.

The Portopia Serial Murder Case is the seminal mystery ADV on the Famicom. As far as I know this game is basically unknown in the West, but it's hugely important. Not only because it essentially created a genre on consoles—there were adventure games on PC, but the command-based interaction system innovated here revolutionized their gameplay and made them suitable for platforms without a keyboard—but also because it was the first meeting between Chunsoft's Horii Yuuji and Enix, the combination which would go on to produce Dragon Quest.

The plot sees you, a nameless detective, and your assistant Yasu trying to solve the murder of the president of a shady loan company in Kobe. The command-based interaction system is a lot to grapple with at first, but once you get used to the menus (which should look very familiar to anyone who's played an 8-bit Dragon Quest title) it plays pretty smoothly. Compared to latter-day ADVs, the plot is thin, but it's still compelling, and contains a surprising final twist that plays cleverly with the player's expectations of the game as a game.

In fact, the shocking ending of Portopia is so famous it's been called "the most famous spoiler in all of Japan," and became something of an early game meme in the 80s. I won't give it away here, so you're gonna have to play Portopia yourself. You'll need a guide, though, because some of these clues are cryptic, especially the "magnifying glass" clues which require you to investigate areas only a few pixels across on certain screens. Apparently the PC version had even harder puzzles, including one where you had to convert a hex number to decimal—maybe not that outlandish today, but definitely utter Greek to most kids playing games in the early 80s.

Even though a clean playthrough of the story takes less than an hour, Portopia is a fascinating game and pretty well-constructed as a mystery to boot. There are plenty of red herrings and non-linear story branches to take, and I didn't see the ending coming. This was played by the likes of Aonuma Eiji and Kojima Hideo and inspired them to create some of the greatest story-focused games of all time. As someone who today loves games like AI: The Somnium Files and 13 Sentinels, it's amazing to see the grandpappy of them all here.

0 notes

Photo

Sanma no Meitantei

Sanma no Meitantei (or “Great Detective Sanma”) is an interesting footnote in the history of early Japanese adventure games. It’s a crossroads of sorts between the release of detective-based murder mysteries inspired by Yuji Horii’s Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken, and – of all things – the Japanese stand-up comedy scene of the mid-80s. This is clear from the get-go, since it stars renowned comedian Sanma Akashiya as the titular great detective, along with a host of famous double acts and comedians of the day who populate the game world.

Read more...

#Hardcore Gaming 101#Apollo Chungus#Review#Sanma no Meitantei#Japanese adventure#comedy#Famicom#murder mystery#Namco#NES#wacky#over the top#video games

123 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Portopia Serial Murder Case (ポートピア連続殺人事件) - Enix - Famicom - 1985

#the portopia serial murder case#portopia#portopia renzoku satsujin jiken#chunsoft#enix#yuji horii#famicom

324 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chunsoft and Sound Novels

I remember when visual novels weren't quite known as well as they are today. By no means are visual novels a mainstream genre of video games--in fact you won’t be hard pressed to find some “expert” try to argue with you over how they are not games at all--but their notoriety is far more than that of even just ten years prior. For the longest time visual novels were seen as just an anime fandom “thing” that mainstream gamers paid no mind to. Very few titles were discussed outside those that had animes be it a TV series or an erotic OVA, and even some of the earliest visual novels localized into English were done so by anime and manga translation companies and not actual video game publishers.

If I had to pinpoint a time in my own memory where the genre started to get noticed more it would be when the Nintendo DS took off. With the DS there was an increase amount of western releases for visual novels thanks in large part to its touch screen interface working well with adventure style games. This wasn't just noticed by Japanese developers either as a fair share of American and European made adventure style games were developed for the console as well. It seems everybody was anxious to utilize the system’s unique features when the DS started soaring in popularity. The point ‘n click and visual novel genres really had a home on the DS, and because of that a lot of people outside of just the anime community got a taste of these kinds of games with beginner friendly titles such as Ace Attorney, Trauma Center, and Hotel Dusk.

However, despite the Nintendo DS (and later to a lesser extent the PSP and PS Vita) giving gamers a finely curated and easily digestible dose of the genre I’d say the sad thing is the push was pretty small and died out quickly. Instead what seems to be the biggest reason why most video game outlets nowadays talk about visual novels are because of the parody dating sims that started to grow in popularity. Hey, do you want to date some monster? Is your girlfriend a llama? Maybe all you need in your life is to date a pigeon. Don’t try to hide it, we all know you secretly wish you could go out with a YouTuber. Not into dorky millennials, well no problem, we got a game for you--that is if dating other people’s dads is a you thing. Yes, this is the era of the wacky, silly dating sims taking over in the English market. It wasn't always like this however, and yes Japan has had a long history of doujin dating sim parodies themselves, but lately it feels like all people know are the parodies that make good YouTube videos to react to instead of what a large amount of the games in the genre can offer.

Don’t get me wrong however, I’m by no means saying parodies do not have a place nor should they stay out of the limelight, and I definitely love that this fad has ushered in a wave of indie made English titles--but simply put this wave lacks so much variety and has been stretched so thin by this point. For every one creative title that pushes boundaries and gets new people interested in visual novels there are ten bland titles spilled all over Steam that feel like they were made by people with barley a grasp on what a visual novel can be outside of either parody dating or “boobies are pretty awesome”. Some of these bland games are even really well made and have a lot of care and attention added to their interfaces and artwork, but when push comes to shove, they are still just a basic joke stretched to its thinnest level. Visual novels don’t have to be that however, and while most mainstream gaming outlets may still be joking about how great it is to date your kitchen appliances, you don’t have to (unless you want to, in which case I recommend dating the toaster for he is the bravest of all kitchen dwellers).

A lot of this misunderstanding can be tied into the nebulous relationship between visual novel and dating sim, two “genres” that many people debate are separate things entirely yet due to the overlapping nature of the two they are often confused for each other. There’s a great article by Brian Crimmins online that actually goes into heavy detail about how visual novels came to be as a genre and how over time both visual novels and dating sims affected and evolved each other. It’s a wonderful read that I really recommend it for anyone curious about games such as these, but either way, whether or not you think visual novels and dating sims are the same thing or should be counted as separate but similar genres of games; it certainly doesn't seem to stop most western gaming outlets reporting solely on gag dating sims as visual novels and taking away a majority of people’s attention from so much more that these games can offer.

I take back all my complaints

I somewhat lost focus and started rambling today, so let’s move on now and finally discuss what I wanted to talk about--that being, despite there being well known visual novel developers to the tight knit community that follows games such as these--examples including but not limited to: Mages, Type Moon, or Nitroplus--my favorite developer often seems forgotten in the conversation. What company is that you ask? Well, it’s Chunsoft. So today I want to talk about why Chunsoft really should be talked about more in the western fandom and all their contributions to the genre.

Chunsoft is one of the many long standing Japanese developers that have been around for every major home console since the Famicom. Nowadays they are known as Spike Chunsoft after their merger with Spike Co. in April of 2012. For the sake of this blog post however I am mostly going to refer to them as Chunsoft still given everything I really want to talk about predates the merger. Chunsoft’s involvement with Japanese style adventure games and visual novels more or less are tied to the very beginning of the genre. There isn't quite a de facto known “first” visual novel per se, but most fans put the starting line at around 1982 or ‘83 depending on which game they may be talking about and which source they want to use for the release date (remember release dates were not entirely clear back in these early days).

One of the earliest contenders for this honor is Yuji Horii’s adventure game The Portopia Serial Murder Case (Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken), a game that was based around Horii’s interest in western style adventure titles, much like Horii’s later known legendary game Dragon Quest was based around his fascination with Wizzardy and Ultima and how to replicate those games in an easier to understand interface for his home nation. It’s here we can see “visual novel” wasn't even a blip on the radar yet, and there was no definitive understanding of what genres for games really were at the time. Portopia proved to be a major hit during its release however and lives on even to this day as a fondly remembered game (and also a Japanese internet meme). Chunsoft handled the porting of the title to the Famicom and this was the beginning of a long business relationship between Chunsoft president Koichi Nakamura and Enix’s own Yuji Horii as in the years to follow Chunsoft would develop the first five entries in the hit Dragon Quest franchise for Enix.

With the birth of the Super Famicom things began to change between both Enix and Chunsoft. Having developed games primarily for the publisher Enix Chunsoft felt they should move into their own publishing, and soon got certification from Nintendo to do so. After slaving away on four Dragon Quest titles on the Famicom, and also working on the fifth title for the Super Famicom, most of the employees at Chunsoft were burned out so they decided their first self published title should be a simple game. Koichi Nakamura wanted to help make gaming more accessible at the time and took both the team’s exhaustion and his desire for a more casual audience into consideration when they moved forward.

The title Nakamura needed to make had to be simple; a game that anyone could be able to figure out to navigate--even those intimidated by a controller, but despite that also needed to take advantage of the more powerful hardware of the Super Famicom by using Kanji scripts which again would make the experience easier on casual players who had trouble getting into video games because game consoles prior could only display text entirely in Hiragana or Katakana making the reading experience poor and hard to enjoy for Japanese players (see Japanese writing systems for more details). To all these ends the team at Chunsoft decided to create a game entirely around reading to tackle this Hiragana issue and show off the hardware (or at least the hardware’s Kanji capabilities) while also being something anyone of any gaming skill level could enjoy. The game would mostly be text for the player to navigate through and present choices at key moments in the story to advance, cutting out any complicated aspects from western adventure style games that might intimidate the unfamiliar such as solving puzzles or finding hidden items. This is how Otogirisō was born.

Otogirisō (Japanese for St John Wort) was Chunsoft’s very first sound novel, a nomenclature which has since confused the hell out of everyone. But what exactly is a sound novel you may ask? Well, people get kind of convoluted about it. Looking at the definition currently found on Giant Bomb a sound novel can be defined by its heavy reliance on sound effects and music to create a game's atmosphere. Usually sound novels will use minimalist visuals and choose to emphasize the text over the artwork presented on screen--most commonly covering the entire screen in said text instead of keeping text only contained in a dialogue box. Something among these lines is the definition usually seen online when you look into it. It’s not entirely wrong either, but it’s also missing something to it. The term sound novel is a creation of Chunsoft themselves, and something they own a copyright on, this is also often brought up when you search sound novel, but at the time of its creation sound novel was meant to be something really easily understood and not this tangled mess of “a certain kind of visual novel”.

When Chunsoft first created Otogirisō the brand sound novel was added to its box in order to help potential customers understand what kind of game it was. At the time it was just a way to let people unfamiliar with adventure style games (more commonly found in the west) to understand that this title will largely feature reading. In fact when Otogirisō was originally shown to the press in a 1991 Nintendo Space World show the game looked radically different from its finished project. Otogirisō was presented mostly as a book that the player would read, pretty much just like modern e-readers are now, with the exception that it included some sound effects and music. The press at the time was underwhelmed by this so Chunsoft took the game back to the drawing board and created unique visual backgrounds to give the game more flair and in doing so set a certain precedence for future visual novels to follow in.

An important factor to remember here is there was no clear cut way to define games such as these yet. The term visual novel had not yet been coined, and even gamers themselves were not very well aware of genres. As Nakamura admits in a Famitsu interview when asked about the creation of sound novels, “if you look back at the very beginning of video games, for me, the conception of “genre” didn’t exist. Take action games, for example: within that label you had shooting games [note: Shoot ‘em Ups], you had stuff like Pac Man and Dig Dug, and you had more puzzle-y games too. It was very diverse. On the same note, with adventure games, there were Ascii Magazine’s games like Ometesandou Adventure and Minamiseizan Adventure, which were pure text adventures… but you also had things like Mystery House, which had a few pictures, or war simulation games like Fleet Commander. I played all those, and while I recognized there were many different types of games, I never thought about it in terms of genres.” So basically, at the time sound novel was conceived it was just meant to be the most straightforward way to define this Japanese style of adventure gaming that Chunsoft was trying out on the Super Famicom.

But does it end there? Well no. That’s only the part of the answer. Otogirisō ended up being a modest sleeper hit upon its release and this lead to Chunsoft to making more sound novels, with their next title being a legendary game that has since eclipsed Otogirisō as the de facto sound novel; Kamaitachi no Yoru (Night of the Sickle Weasels). This game was a hit, there’s no easy way for me to describe just how big it really was back during its release--out of the pantheon of legendary Japanese games that people in the US and Europe know jack about Kamaitachi no Yoru is one of the highest. Kamaitachi no Yoru is a fantastic game and I talked about it ad nauseum a few years ago when I payed the localized version called Banshee’s Last Cry, check that out if you’d like to know more, and if you’re still somehow able to play it then you’re definitely in for a darn good time.

With the a string of successes in the visual novel marketplace after both Otogirisō and Kamaitachi no Yoru, Chunsoft kept churning out games over the years, many of which are highly respected by the fandom still such as Machi and 428: Shibuya Scramble. All these releases of theirs had a certain tone and atmosphere, not to mention a distinct presentation that didn’t change much over the years and because of that did not look like what visual novels typically look like now. There’s a certain charm and narrative style between all of Chunsoft’s sound novels that is a really strong defining link in their catalogue despite a lot of these games being stand alone--and because of that people come to expect certain things upon seeing the term sound novel. Many titles would eventually come out not made by Chunsoft that shared similarities to their brand--these games followed in the footsteps of Chunsoft’s tone, structure, style, and presentation--and people began to notice, the most famous of which being 07th Expansion’s Higurashi doujin series. This is where we begin to see that murky kind of convoluted aspect of sound novels, as they start to transcend a basic label put on a box almost three decades ago and turn into their own little sub genre or maybe better described as their own style of visual novel.

So what the heck is a sound novel then? The simplest answer is a sound novel is a dated term that Chunsoft used regularly and has since fallen out of use for visual novel; the more complicated answer is that sound novels are both a term used by Chunsoft for their brand of visual novels back before the term visual novel existed and also a certain style of visual novel that is mostly inspired by the early Chunsoft games’ presentation and ambiance.

Top Left to Right: Otogirisō - Chunsoft '92, Kamaitachi no Yoru - Chunsoft '94, and Machi - Chunsoft '98 Bottom Left to Right: Higurashi When They Cry - 07Expansion 2002, Tsukihime - Type Moon 2000, and GeGeGe no Kitaro Maboroshi Fuyu Kaikitan - Bandai '96

Over the years Chunsoft has expanded, changed, and moved beyond their sound novel brand. Despite this however, they have never really stopped putting out solid titles in the visual novel market, and it seems like each new generation of gaming is blessed with at least one visual novel of theirs. My personal favorite title out of all their work from this era would definitely have to be 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors on the Nintendo DS. It was because of this game in particular that my love of visual novels in general really started, and Kotaro Uchikoshi’s sharp writing--especially the incredible dialogue and thorough thought narration in protagonist's Junpei’s head still stands at the peak in my mind. Throw in beautiful sprite work based around art from legendary Capcom (and now freelance) artist Kinu Nishimura, and a fantastic soundtrack from the man himself, Shinji Hosoe and you got yourself a meeting of some fantastic minds. I've written about 999 in the past, and you can read about it here, but I still want to write more about it in the future, especially tackling the latest release it got in 2017’s Zero Escape: The Nonary Games.

Recent years have seen Spike Chunsoft make it big with their Dangan ronpa franchise, admittedly however the first Dangan ronpa title should be more attributed to Spike, as the game was released in 2010 two years before their merger. However the two companies together as one have since released three more Dangan ronpa games, and two (or is it three?) Dangan ronpa anime titles, and many, many rereleases and compilations. My own interest in the franchise isn't nearly as strong as everyone else’s seem to be but I did however absolutely adore the last game, Dangan ronpa V3, with how many times it managed to jump the shark, upping the game, and constant plot twist after more ludicrous plot twist. If there was ever a way to end something like Dangan ronpa it was what that game did, and oh boy did I get a kick out of that.

Finally moving past Dangan ronpa, 2019 will see Spike Chunsoft develop and publish Kotaro Uchikoshi’s newest game, AI: The Somnium Files, for the Nintendo Switch, PS4, and Steam which just got its newest trailer and release date announced earlier this week. I am very excited for it personally and love the intricate and complex alternate reality game type marketing the team has been using to build up to its release! This is some next level stuff, and has been tons of fun all on its own.

Then there’s of course one more game I simply cannot pass up mentioning, 428: Shibuya Scramble. Now I briefly spoke this title earlier mentioning later sound novels that have been highly acclaimed, and trust me 428 is definitely beloved; its perfect score in Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu really meant something back in 2008 on the Wii. But why mention this with recent Spike Chunsoft games? Well the answer is easy, 2018 saw the much beloved, super Japanese game finally get an American and European release! And much celebration was had! If anything in this whole blog post remotely sounded interesting to you I really implore you all to go check it out either on the PS4 or Steam, and see what a Chunsoft sound novel is all about. And for the impatient, I will be writing about it next on blog!

Despite Chunsoft changing over time and no longer using their sound novel brand, they have still put out many classic and fantastic games in the visual novel genre. Their later work may take a radically different presentation from their prior titles, but despite their moving away from that set style there are still other developers out there that keep up that mantle. Overall I think the effect Chunsoft has had on the genre is undeniable and anyone missing out on their catalogue of fantastic titles are really missing on some of the best titles visual novels have to offer. That’s why I really wanted to write this blog post about them and put into words my thoughts about this developer’s library that just seems so often overlooked by many others in the fandom, at least in my experience. I hope through all my grumbling, and “kids today” rant I was able to at least get somebody interested in trying out one of their games.

#428#428 Shibuya Scramble#999: Nine Hours Nine Persons Nine Doors#999: 9 Hours 9 Persons 9 Doors#999#Banshee's Last Cry#Chunsoft#Spike Chunsoft#Danganronpa#Higurashi When They Cry#Kamaitachi no Yoru#Koichi Nakamura#Kotaro Uchikoshi#Nintendo DS#Otogirisō#Otogirisou#Portopia#The Portopia Serial Murder Case#Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken#sound novel#video games#visual novel#visual novels#VN#Zero Escape 999#Zero Escape

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backblog #15 - Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken (NES)

As mentioned previously, this time we have Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken, known in English as The Portopia Serial Murder Case. Developed by Yuji Horii of Dragon Quest fame (and the Famicom version by Chunsoft) and published by Enix in June of 1983, it was originally released on the NEC PC-6001 before being ported to numerous other Japanese PCs and then eventually the Famicom (the version I played, thanks to a translation patch from DvD Translations), all in Japan only, of course. More recently, a full remake was released on Japanese mobile phones alongside two other games (Hokkaido Rensa Satsujin: Ohotsk ni Kiyu and Karuizawa Yuukai Annai) from the Yuji Horii. It is among the earliest games in the visual novel genre (the only games on vndb.org actually listed as being released earlier are Lolita: Yakyuuken and Lolita 2 by PSK and only the second one of those is anything more than strip rock-paper-scissors). For this and a litany of other reasons, it is among the most important early releases in Japanese gaming history.

During his time as a journalist for a video game column for Shonen Jump, Yuji Horii entered a game programming contest held by the then brand new company, Enix, in order to source talented developers and build their initial library of games. Horii managed to place in this contest with Love Match Tennis. Another big player also came out of the contest in the form of Koichi Nakamura with his puzzle game, Door Door, which featured a player character named Chun, who ended up becoming the namesake of Nakamura’s development contracting company, Chunsoft. Together, the winners of the contest all used their prize, a trip to the United States, to attend the 1983 Applefest in San Francisco. It was here that Horii encountered the western computer RPG, Wizardry, which proves to be very important later.

Soon after Enix’s initial spree of releasing all of the contest games for a wide variety of Japanese PCs, Horii ended up working on Portopia. He derived the concept of the game after reading in a PC magazine about interactive fiction games in the west, such as Zork, and deciding it was an untapped market in Japan. Portopia was designed to be his take on that genre, even featuring a simple “verb noun” text parser. One of his major additions to that style of game was graphics depicting the current scene in the story: the “visual” part of “visual novel.” He also wanted to use the opportunity to experiment with more non-linear storytelling, which was sorely lacking in Japanese games at the time. The game was programmed in BASIC and released for various Japanese PCs over the course of 1983 and 1984 to great success, laying the foundation for the entire visual novel genre. A lot of early visual novels even share the mystery theme of this one.

After the Famicom was released and Enix started porting some of their games to it, Horii wanted to make a game in the style of Wizardry for it. However, Enix felt that the Famicom was still too much of an action platform compared to PCs and they weren’t sure how well a game of that type would do. So, it was decided to first go with the cheaper option of porting Portopia to the Famicom to see how a more adventure-oriented game fared in that market. Horii teamed up with Nakamura’s Chunsoft and work on the port began. One of the major additions to this version was an underground maze section in the style of the Wizardry games used to test the Famicom’s ability to handle something like this. Upon release, the Famicom version of Portopia, of course, also did extremely well and Horii was allowed to work on Dragon Quest along with Chunsoft, which itself became the template for all future JRPGs. So, in addition to kicking off the visual novel genre, its continued success ultimately led to what we now think of as a JRPG. Granted, Dragon Quest isn’t the very first Japanese RPG, The Black Onyx predates it by a few years for example, but it was certainly the most influential. And hell, if that weren’t enough, Portopia is also one of the games that inspired Hideo Kojima of Metal Gear fame to enter the game development scene after he was moved by its storytelling.

The story of the game itself (as told in the manual, since the game itself starts off with the case already having begun with no immediate context) is that Kouzou Yamakawa, the president of a loan shark company in Kobe, was found in his home by his secretary and security guard, dead from a stab wound to the neck. Because he was found in a room that was locked from the inside, the obvious conclusion is that it was a suicide, but owing to his position, the man did have a lot of enemies, so it falls to you, an unnamed veteran homicide detective to investigate. You spend the game searching the murder site and the surrounding cities, gathering clues, interviewing suspects, and establishing motives, hoping to determine the culprit of the crime, if there even is one. It’s a classic sealed-room murder mystery.

As you explore the game and perform your investigation, it is actually your subordinate Yasuhiko Mano (or Yasu for short) through whom you interact with the world by commanding him to perform various functions. In the original game, as mentioned above, this is done by a simple text parser, but since this isn’t really a possibility for the Famicom, that version instead has a large menu of all of the actions you can ask Yasu to perform. The actions include: move, ask, investigate someone, show item, look for someone, call out, arrest, investigate thing, evidence, hit, take, theorize, dial phone, and close case. Some of these are more important than others. For example, I don’t remember “look for someone” ever being successful over the course of the whole game, whereas investigate someone is important for learning new bits of information and investigate thing is important for gathering new clues. Theorize is another command that’s never technically necessary during the game but it can serve to give the player some hints.

Possibly the most frustrating facet of the game is the fact that selecting investigate thing and then selecting magnifying glass brings up a magnifying glass cursor that you use to actually select a point on the screen. I would say this creates an irritating example of pixel-hunting but I can’t even really call it that because sometimes there isn’t even a pixel. Sometimes when this needs to be done to find a new piece of evidence, you’re required to select a spot on the screen where there doesn’t appear to be anything at all. Adding to this is the fact that it can be pretty specific where you actually need to search. It might not be enough to search under a table, instead requiring you to search a pretty small region under the table. I obviously wouldn’t mind this if there were any visual cue, but sometimes there just isn’t. It isn’t a huge aspect of the game by any means, but whenever I did get stuck, it was almost always because I didn’t meticulously comb every inch of some screen. To be fair, I believe every time this comes up is on one of the locations in or around the house where the victim was found dead, so it does make sense that I should have been much more thorough with the magnifying glass there of all places.

The structure of the game is actually surprisingly open. You can more or less go anywhere in the game and find clues there or interact with the characters at any time. However, you still have to proceed with the main story linearly. Oftentimes, the aspect of the game that controls the flow of the story is events that occur in the police station at different times. For example, one of the suspects is one of Yamakawa’s clients that has been reported as missing and you can learn about him and start to follow that lead pretty early on. However, until you eliminate suspect of the first act of the game you can’t trigger the flag for the event in the police station that gives you the clue to find out where the missing client is and eliminate him. This structure is something I experimented with for a while during my playthroughs of the game. Even though you can almost completely set up the chain of events that ultimately leads to solving the case from the very beginning of the game, you end up missing one tiny little thing that lets you completely follow through with that lead until you proceed as normal.

Another big new aspect of the Famicom version of the game, as mentioned above, is the large Wizardry-style first-person maze located underneath the Yamakawa mansion. Like a lot of the game, you can access this pretty early on, but the most important part of it is still inaccessible, again via an event at the police station, until you complete the rest of the story. It’s a fairly complex maze and can be pretty easy to get lost in. This is mostly because of the sudden transition as you move square to square. It looks pretty natural when you’re just moving forward, but when doing turns, especially 180-degree turns, you can get pretty disoriented. To be fair, the same can be said of Wizardry, but it can be pretty hard to get used to after playing something like Phantasy Star where the animation for moving through the maze is much smoother and feels more intuitive. The maze does contain a Wizardry-style message (that turns out to be graffiti) saying that you were surprised by a monster, which is pretty amusing.

The true culprit, once you finally do cross off all the other suspects and find out who it is, is actually a pretty neat twist. It was considered so shocking at the time that it pretty quickly became a meme, even appearing as a gag in the manga, Rozen Maiden. It also served as the namesake for a character in another well-respected mystery visual novel, which I won’t reveal the name of, lest I spoil both of them. Unfortunately for me, I did go into the game already knowing the identity of the culprit, having been spoiled on it ages before ever even intending to play the game just due to how much of a cultural phenomenon it is, but it’s still a good story, with well thought out character motivations, and the lead-up to that revelation is cool nonetheless.

As mentioned above the graphics pretty much just consist of simple illustrations of the current scene of the story, with minor additions for some scenes, such as the ability for multiple characters to show up in the interview room in the police station. In the original PC versions, these graphics were drawn using lines and fills, looking somewhat like MS Paint drawings that took quite a while to be drawn on the screen, probably due to having to read from the disk. The graphics of the Famicom version are still crude (owing to not using any mapper chips to extend the Famicom’s graphical capabilities, which did make the game extremely cheap to produce), but less so, and loaded much faster. And I can certainly forgive crude graphics for such an early title. Probably the more unfortunate fact is that the game contains zero music. The only sound effects in the game at all are the sirens at the beginning and end, the noise that plays for the text scrolling, and a few sound effects in the maze. It makes the whole thing feel pretty lonely, which may or may not be intentional. The mobile phone versions did add music though, so there is that if you can find it.

Overall, apart from being an extremely important game it actually is a fun game with a good story. I’d definitely recommend it, especially if you’ve managed to avoid spoilers. It’s pretty short and can be beaten in a couple of hours at most, which is good since there’s no save function of any kind. Up next is a game that I’ve already finished just the other day, Princess Tomato in the Salad Kingdom, so the write-up should be rolling out pretty shortly.

Links:

DvD Translations’ Fan Translation - In addition to containing the translation patch itself, the readme also included a lot of contextual information on the game, much of which made it into this post.

#text post#backblog#backlog#backloggery#video games#yuji horii gekijou#yuji horii theater#yuji horii mysteries#portopia renzoku satsujin jiken#the portopia serial murder case#chunsoft#enix#yuji horii#koichi nakamura#nintendo entertainment system#famicom#adventure#visual novel

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Portopia by Legowelt (aka “He Of Way Too Many Aliases”).

He released this under the name Satomi Taniyama, who was supposedly a garbage man from Oda who made an album inspired by the Portopia Serial Murder Case adventure game, using instruments he’d found discarded on the job.

#Portopia#Portopia Serial Murder Case#Legowelt#Satomi Taniyama#Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken#Electronic Music#Electronic Ambient#Minimal#Video

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

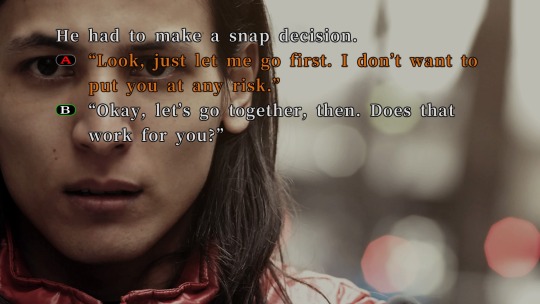

Flyer for the HAL Laboratory 1988 game ‘Satsui no Kaisou: Power Soft Satsujin Jiken’. This graphical adventure is one of the most notable offspring from Yuji Horii’s highly influential ‘Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken’. However, its style and interface were somewhat more in line with murder investigation games of the late ‘80s such as Data East’s ‘Tantei Jingūji Saburō’, the first of a long-running series; or Namco’s ‘Sanma no Meitantei’, both hitting the market the previous year.

The player assumes the role of a young police detective by the name Akito Kashibatake, who is informed that an old friend was found dead at the Jogasaki coast cliffs, apparently as a result of a suicide. Upon examining the scene, he suspects foul play and initiates an investigation. The game takes place over a period of three days, during which the player must resolve the case and avoid a game over outcome. As the story unfolds, additional murders take place, creating a sense of urgency and tension. As each action taken by the player advances the clock a few minutes, finding the perpetrator can only be achieved by taking a strategic and sequential approach. This unique system also made the game particularly difficult, one of the reasons why it was not as popular as its contemporaries. The relatively poor market performance led to the cancellation of an initially planned sequel.

The artwork beautifully captures not only the element of time in association with death, as symbolized by the hanging rope that replaces the pendulum of the antique wooden clock, but also the shock of the initial scene in which the friend’s corpse is discovered by the sea. It also proposes an interesting rendition of the main character that turns the turn of the decade police detective stereotype on its head. The game concept and story originated at Hyperware, a small software house nested in the University of Tokyo, under the direction of Theoretical Science Group, creators of the Apple II version of the legendary 1979 arcade game,Heian-kyō Eirian. Touchingly, the HAL Laboratory website still reserves a small corner where visitors can discover more about the game.

#Satsui no Kaisou: Power Soft Satsujin Jiken#Satsui no Kaisou#hal laboratory#famicom#murder investigation#video game#1998

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken

©️ Chunsoft / Enix (MSX 1985 / Mobile 2003 / Mobile 2005)

Image sourced from hardcoregaming101.net As seen in the fourth episode of Pop Team Epic season 2.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken Año: 1983 Plataformas: MSX, NES, NEC PC-8801, Sharp X1, FM-7, NEC PC-6001

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(vía https://twitter.com/chou_nosuke/status/529644636432650240)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Quest May 27, 1986 // Family Computer

We're finally here, where it all begins. The console RPG is arguably the most quintessentially Japanese video game genre, and Dragon Quest is inarguably the most quintessential console RPG. You could say that DQ is the genre boiled down to its most basic components, except there was nothing to boil down from at the time. Horii Yuuji and Nakamura Kouichi were really creating a new genre from scratch, and a lot of the peculiarities of DQ from a modern perspective are a result of this. For example, it seems absurd to have separate commands for "open door" and "go up stairs" and "investigate" and "talk" (which would all be handled with a single button, or no button, in a modern game) but it was seen as necessary to simply let the player know these are things they can do—particularly talking to NPCs, which is very important for following the game's main story, but had rarely been a big part of a console game to this point, except maybe in Horii's Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken, to which DQ owes a lot.

So for the modern player who is completely used to the conventions of role playing games, Dragon Quest feels extremely barebones but it is not a bad game by any means. The game feels like something that might be implemented as an "idle RPG" today. You grind, watch number go up, and buy the next equipment so you can grind even more and buy the equipment after that. There is a lot of grinding required, though, and even as someone who likes grinding in RPGs I started to get bored around level 12 or so. Still, this game is single-handedly responsible for defining what an "RPG" meant in Japan and is really required reading for anyone who considers themselves a fan of Japanese RPGs.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken

In a cutscene at the end of Metal Gear Solid V, a game set in the 1980s, a man is loading a cassette tape in MSX computer and the characteristic loading noises from a data tape are played. It did not take fans long to find out that the audio contained the header of the 1983 Japanese adventure game The Portopia Serial Murder Case, a game Hideo Kojima famously has quoted as one of the reasons he went into the video game industry. In fact, this by modern standards rather primitive graphical text adventure is often heralded as one of the most influential games in Japanese video game history. Similar to how Sierra’s King’s Quest (1984) shaped the direction western computer adventure games would take, Portopia has been instrumental to the development of the adventure (ADV) genre, but also to Japanese video game interface design in general.

Read more...

#hardcore gaming 101#daniel brink#review#portopia renzoku satsujin jiken#japanese adventure#text adventure#fm-7#historically important#japanese pc#msx#murder mystery#famicom#pc-6001#pc-88#pc-98#sharp x1#video games

203 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Portopia Serial Murder Case running on a NEC PC-6001 mkII.

49 notes

·

View notes

Video

A prova do crime esta no cartucho de Famicom. Mais informações

1 note

·

View note