#Pamela Bannos on Vivian Maier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

#Pamela Bannos on Vivian Maier#The Great Women Artists#podcasts#podcast#women in art history#women artists#art history#katy hessel#history#20th century art#20th century#photographer#photography#Vivian Maier

1 note

·

View note

Text

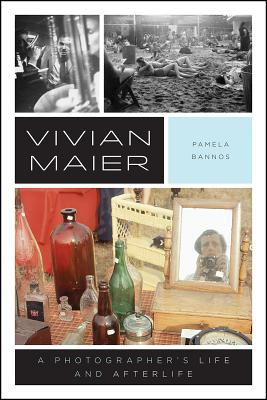

Pamela Bannos Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vivian Maier: The Creative Personality Versus the Persona

— Written by: John Paul Jonas

In New York, the retrospective of Miss Vivian Maier (1926-2009), titled “Unseen Work,” recently concluded. The exhibition was open to visitors from May 31 to September 29, 2024, at the “Fotografiska New York” museum. The showcase included around 230 works covering the period from the early 1950s to the late 1990s, featuring many previously unseen photographs.

The exhibition highlighted Miss Maier's distinctive style and her extraordinary ability to capture the essence of everyday life through an artistic lens. It is part of a larger effort to bring her work to a wider audience, especially considering that her vast body of work was only discovered posthumously, yet it is already considered one of the most important contributions to 20th-century photography.

Organized in partnership with cultural institutions such as the John Maloof Collection in Chicago and the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York, this retrospective is part of an international tour that began in Paris in 2021.

Over the past 15 years, since the discovery of her archive, Miss Maier’s remarkable life story has captivated the international art community. Why?

Miss Maier was an American street photographer of French descent, born in 1926 in New York. She spent most of her life working as a nanny in Chicago. During her time off or on walks with the children she cared for, she dedicated herself to photographing the urban life around her, capturing candid and unfiltered moments of city life.

Although she remained unknown during her lifetime, her extensive archive—comprising over 150,000 negatives—was discovered in 2007 when Mr. John Maloof acquired the majority of her work at an auction. Fascinated by his discovery, Mr. Maloof became the driving force behind promoting her photographs, leading to the production of the Oscar-nominated documentary Finding Vivian Maier in 2013. Since then, interest in her extraordinary life and work has only grown. Following years of research, two comprehensive biographies have been published: Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife by Pamela Bannos in 2017 and Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny by Ann Marks in 2021.

In his renowned work On Liberty, John Stuart Mill reminds us: “Among the works of man, which human life is rightly devoted to perfecting and beautifying, the first in importance surely is man himself.” This observation aptly applies to the life and work of Miss Vivian Maier.

Anne Morin, curator of the exhibition Vivian Maier: A Photographic Revelation, shown across Europe, claims that Miss Maier is “one of the top street photographers, ever.” “Her story is definitely amazing, but I have to work hard to keep it separate from the physical reality of her photographs.” (Morin, as cited in Casper, 2014) [1] While I have no doubt about the sincerity of this intention, I fear such efforts may be in vain. Miss Maier’s most significant achievement is, indeed, her extraordinary life story. The art of photography forms the backbone of this narrative. It gave meaning to an otherwise unremarkable life—perhaps the highest gift art can bestow upon its creator.

“When we are involved in [creativity], we feel that we are living more fully than during the rest of life,” observes Professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, adding, “Even without success, creative persons find joy in a job well done.” [2] For an artist, separation from their art is a kind of torment, a confrontation with the meaninglessness of existence. When Miss Maier’s photographic walks ended in success, her daily duties as a nanny likely became less tedious and futile. The world’s imposed tasks could be viewed as necessary preparations for the next round of creation. A reasonable compromise.

Professor Csikszentmihalyi also suggests that no one can be both exceptional and normal at the same time. Miss Maier separated these two aspects of her life for the sake of survival—a creative compromise. For those around her, including the families she worked for, she presented herself as an unmarried yet proud modern woman, unusually interested in various aspects of contemporary life. “The personal accounts from people who knew Vivian are all very similar. She was eccentric, strong, heavily opinionated, highly intellectual, and intensely private. She wore a floppy hat, a long dress, wool coat, and men’s shoes and walked with a powerful stride.” [3]

Well-informed and empathetic toward the oppressed, she was diligent in imparting knowledge to her charges, often addressing challenging topics. Their walks included visits to impoverished parts of the city, with open discussions about current issues. Some audio recordings of these conversations, conducted in the form of interviews, were found among the artist's belongings. Similar efforts are confirmed by Mrs. Nancy Gensburg of Highland Park, whose three sons (John, Lane, and Matthew) were cared for by Miss Maier: “She wanted them to be very aware of what was going on in the world.” [4]

The artist’s identity intertwines significantly with her role as a caregiver, a profession that financially sustains both sides of her life. This unusual nanny finds ways to navigate the demands of daily life. At this stage, the dichotomy between her two personas isn’t yet fully expressed. It even seems that, in a harmonious blend, the creative personality might enrich the life and professional standing of the governess. As a photographer, she grants herself permission to dedicate valuable time, energy, and resources to a project that, at the very least, jeopardizes the practical survival of her career as a childcare provider. Always seeking knowledge and intellectual challenges, the artist approaches her vocation with both dedication and apparent detachment. “She captured politicians on the campaign trail (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, LBJ); celebrities at premieres or out in the wild (Frank Sinatra, John Wayne, Greta Garbo, Audrey Hepburn); laborers and commuters; drunks, criminals, and down-and-outs; flâneurs [*] and well-coiffed women in furs”. [5]

The initial enthusiasm seems well-balanced and clearly directed. The financial support that Miss Maier manages to secure through her profession as a governess is apparently supplemented by a modest family inheritance. It appears that resources to fuel her creative spark are not lacking—quite the opposite. She frequently takes advantage of opportunities for extensive travel, during which she further broadens her intellectual horizons. These odysseys stand in stark contrast to the otherwise modest habits of the nanny. “Her thirst to be cultured led her around the globe. At this point we know of trips to Canada in 1951 and 1955, in 1957 to South America, in 1959 to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, in 1960 to Florida, in 1965 she’d travel to the Caribbean Islands, and so on. It is to be noted that she traveled alone and gravitated toward the less fortunate in society”. [3] The families she worked for generally viewed such excursions with leniency, tolerating the whims of their young, unmarried, and headstrong caregiver. “If she wanted to go, she’d just get up and go,” Nancy recalls. “The family would hire a temporary replacement while Maier was away; she never said where she was headed”. [4]

During her creative expeditions across the globe, Miss Maier photographed tirelessly. It is likely that during this period of intense travel and creative freedom, a strong artistic personality fully took shape. The desire for unrestricted movement and an independent choice of vocation remained powerful even upon her return to the role of governess. The families she worked for began to sense a shift in her approach to daily duties; unfortunately, the other Miss Maier—sensitive, original, and above all, productive—became inaccessible, even to those closest to her. “She really wasn’t interested in being a nanny at all,” Nancy Gensburg says. “But she didn’t know how to do anything else.” [4] The second part of this statement now seems both untrue and harsh. Many creative individuals who were not recognized in their own time face similar misconceptions. In Miss Maier’s case, we ask ourselves to what extent the artist herself is responsible for hiding her achievements from public view.

Based on the relatively sparse evidence currently available, we conclude that Miss Maier’s early creative work was far more visible and accessible, at least to those in her immediate surroundings. “There’s one family in New York that has hundreds of vintage Vivian photographs. In Chicago, she’d give people like two at the most. So she was much more generous and open with her photography in New York.” (Marks, as cited in Reid, 2021) [6]

It is evident that the pressures of daily life grew stronger with time. The creative personality would occasionally retreat, and the artist often made concessions. For example, in her creative process, she gradually abandoned post-production. The selection and processing of photographs, printing reproductions, and even developing negatives became increasingly unavailable luxuries. “In 1956, when Maier moved to Chicago, she enjoyed the luxury of a darkroom as well as a private bathroom. This allowed her to process her prints and develop her own rolls of B&W film.” [3] This convenience extended her control over the creative process—from capturing the image to developing the prints. The initiative of transforming her bathroom and sacrificing personal comfort demonstrates her deep commitment to accessing resources scarce for an artist in the social role of a nanny. Miss Maier consistently exhibited an undeniable dedication to learning, refining her artistic methods, and perfecting her technique. It wasn’t merely an exploration of her own vision of the world through the lens, but a sincere effort to realize, materialize, and ultimately present that vision to the people around her.

The seriousness of her intention to make some income from photography is evident in the fact that a number of her works were prepared for sale during post-production. “If you wanted a picture,” Nancy says, “you had to buy it. But Maier wasn’t selling her photography for profit. Someone had to want it more than she wanted it. It’s like an artist who would paint something and then hate to get rid of it. She loved everything she did.” [4] I doubt the comparison to a painter is quite fitting. We know that photographs can be reproduced an unlimited number of times. For similar reasons, visual artists create graphic works. Each print is authentic because it bears the artist's signature and a unique serial number from a limited edition. It’s likely that behind this apparent reluctance to sell her work lay different motivations. Perhaps Miss Maier wasn’t yet ready for this form of commerce—without an official representative, gallery, or agent who could properly assess the specific value. If that’s the case, maybe she was still waiting for the right opportunity to present herself to the world ‘the proper way.’ Perhaps the value she sought to achieve in the eyes of her contemporaries wasn’t financial. She was aware of her talent but lacked recognition.

Unfortunately, her working conditions during the later period were not as favorable. "As she would move from family to family, her rolls of undeveloped, unprinted work began to collect." [3] The creative process was diminished. From this period, the stereotype of the artist who creates out of an inner necessity, without any clear intention of sharing their work with the world, began to emerge. This complex dynamic between dedication to the art and neglect of the result creates the popular narrative about Miss Maier’s rich and self-sufficient inner world. Sophie Wright, the New York museum’s director, tells CNN: “There’s no audience in mind. There is no evidence that Maier wondered about her viewers—or that she ever imagined having viewers in the first place.” (Wright, as cited in Wexler, 2024) [7]

Professor Csikszentmihalyi reminds us that creative people are often intelligent but, at the same time, extremely naive. It is likely that the refined cultural habits she developed played a role in shaping and protecting her creative self. However, these habits also created a clear separation between her artistic identity and her social persona. This unintentional division left her vulnerable, deprived of understanding and support from the ‘ordinary’ world. “I once saw her taking a picture inside a refuse can,” talk show host Phil Donahue, who employed Maier as a nanny for less than a year, told Chicago magazine. “I never remotely thought that what she was doing would have some special artistic value.” (Donahue, as cited in Wexler, 2024) [7]

However, Miss Maier did not allow people or circumstances to take away her initial creative spark and authentic raison d’être. The boundary was clearly drawn on that front. “Her relationship with the world occurred through the camera, through the process of photographing/filming her surroundings,” comments Anne Morin, adding, “But once the recording was finished, she wasn’t as interested in looking at the result.” (Morin, as cited in Casper, 2014) [1]

The truth is, we will never know how painful the concessions to reality were. Was the act of photographing alone enough for Miss Maier? Could she truly choose? Or were choices made on her behalf by social and economic circumstances, as well as her marginalized position? While she carefully observed the world, no one saw her work after the photographs were taken—not even the artist herself.

It seems that the transition to color photography finally marked the quiet abandonment of any plan to enter the artistic scene, if such an intention ever existed. “Her color photographs focus on the musicality of the image, the forms, the density of the colors. She was really working in the medium of color when she took color photographs. In her black-and-white work, her focus seems to be on her subjects, the people pictured.” (Morin, as cited in Kasper, 2014) [1]

During this later period, faces gradually disappear from her photographs, giving way to abstract compositions in vibrant colors. Their artistic value is not diminished, but the sensibility has changed. If she had failed to connect with her contemporaries by skillfully capturing their portraits in scenes from everyday life familiar to everyone, that chance was certainly reduced by her prevailing choice of new subjects. In the bustling urban environment, there were plenty of themes, and Miss Maier gave due attention to each, despite the evident divergence from popular taste. “She cataloged the textures and cast-offs of the urban environment: graffiti, fire escapes, signs, garbage, shadows, abandoned newspapers, half-demolished buildings. She easily switched between registers.” [5]

We sense that an antagonism has always existed between Miss Maier’s creative self and her social mask, occasionally softened by fortunate circumstances. Finally, at some mysterious crossroads in her life, these two constructs tragically diverged. Instead of complementing and supporting each other, they grew apart. The artist gradually became a practical burden for the nanny. “When she interviewed with Zalman, a math professor at the University of Chicago, and Karen, a textbook editor, she made one thing clear: ‘I have to tell you, I come with my life, and my life is in boxes.’ No problem, they replied. They had a spacious garage. ‘We had no idea what we were in for,’ Zalman recalled. ‘She showed up with 200 boxes.’” [4]

Without the ability to bring her creative passion into the open, the “normal” nanny Maier was forced to endure. Proud and independent, she gradually retreated into a form of self-imposed exile toward the end of her life, relying on the goodwill of others. The rent for her final apartment was paid by the three brothers she once cared for, who remained deeply fond of her. Even they were unaware of her massive body of work. She rented storage lockers where she kept an enormous collection of negatives, photographic equipment, and numerous audio and video recordings. After a severe head injury from falling on ice around Christmas in 2008, she spent her last days in an emergency room. The three boys from Highland Park visited her daily. Their mother, Nenny Gensburg, noted: “She really was a unique person, but she didn’t think anything of herself.” [4]

When the rent on her storage lockers was not renewed, Miss Maier’s artistic legacy was auctioned off while she was still alive. No one in her circle knew anything about it. The secret was kept.

Why didn’t she confide in the people who embraced her? Would the world have collapsed? Yes. Her world would have. The carefully built facade would have crumbled irreversibly. She didn’t allow that, even when the remedy finally turned into poison. Her insecurity about her place in the world, perhaps rooted in her dysfunctional childhood, led to distrust and withdrawal from others. The world didn’t recognize the artist. It tolerated the well-read but eccentric persona. For the nanny, that was enough.

On the other hand, we wonder: during those fruitful decades, did the controlled “schizophrenia” between her private and public selves drive the engines of her vibrant and original creativity? Did the friction between these strange poles of existence generate the spark of creation? I believe this is beyond doubt.

The artist and the nanny courageously carried out their mission to the end. It is now up to the world to embrace and reconcile them, and finally display with pride the photographs from an unparalleled time capsule.

I'm an independent writer, and any contribution counts! If you enjoyed my work, you can buy me a coffee @ Ko-fi →

[1] Casper, J. (2014, July). Vivian Maier: Street photographer, revelation. LensCulture. Retrieved from:

https://www.lensculture.com/articles/vivian-maier-vivian-maier-street-photographer-revelation

[2] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperCollins.

[3] Maloof Collection, Ltd (n.d.). About Vivian Maier. Vivian Maier. Retrieved from:

https://www.vivianmaier.com/about-vivian-maier/

[4] O'Donnell, N. (2010, December 14). The life and work of street photographer Vivian Maier. Chicago Magazine. Retrieved from:

https://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/January-2011/Vivian-Maier-Street-Photographer/

[5] Lybarge, J. (2021, Dec 21). The Trouble With Writing About Vivian Maier. The New Republic. Retrieved from:

https://newrepublic.com/article/164770/vivian-maier-photographer-biography-review

[6] Reid, K. (2021, Dec 7). Writing the True Story of Vivian Maier’s Life. Chicago Magazine. Retrieved from:

https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/december-2021/writing-the-true-story-of-vivian-maiers-life/

[7] Wexler, E. (2024, July 9). Meet Vivian Maier, the reclusive nanny who secretly became one of the best street photographers of the 20th century. Smithsonian Magazine. Preuzeto sa:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/meet-vivian-maier-reclusive-nanny-street-photographer-20th-century-180984665/

[*] Flâneur is a French term that refers to a person who strolls leisurely through urban spaces, observing and experiencing the surroundings without a specific destination or purpose. This concept embodies the idea of leisurely exploration, allowing the flâneur to engage with the environment in a reflective manner. Often associated with 19th-century Parisian culture, the flâneur is viewed as a detached observer of city life, embodying the spirit of modernity and the complexities of urban existence.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Trouble With Writing About Vivian Maier

Biographers get distracted by the photographer’s unusual life story—to the point of diminishing her work itself.

Until 12 years ago, the photographer Vivian Maier was largely unknown. Though she shot incessantly from 1950 until about a decade before her death in 2009, she hid her pictures, literally locking them away. Often, she didn’t even bother to develop her rolls of film. She made money as a live-in nanny for families in New York and Chicago (briefly working for talk-show host Phil Donahue). As she got older, she rented storage lockers to house her overwhelming accumulation of books, magazines, newspapers, and other miscellany. The contents of those lockers were auctioned off in 2007 after she fell into arrears, which is how then-26-year-old John Maloof, a former art student, began purchasing the bulk of Maier’s archive: more than 140,000 images, most of them undeveloped and unprinted. A couple of years later, he uploaded some of the pictures to a street photography group on Flickr to immediate acclaim.

The images arrived already imbued with the aura of permanence. They sometimes evoke the wanderlust of Robert Frank’s photos, the wry self-deprecation of Lee Friedlander, or the grubbiness of Weegee, but they’re not derivative. Attentive to plaintive or absurd interludes in American life, primarily in New York City and Chicago, Maier made a piecemeal record of the sudden encounters and furtive gestures that turn any street into a guerrilla theater. She captured politicians on the campaign trail (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, LBJ); celebrities at premieres or out in the wild (Frank Sinatra, John Wayne, Greta Garbo, Audrey Hepburn); laborers and commuters; drunks, criminals, and down-and-outs; flaneurs and well-coiffed women in furs. She cataloged the textures and cast-offs of the urban environment: graffiti, fire escapes, signs, garbage, shadows, abandoned newspapers, half-demolished buildings. She easily switched between registers, from gentle wit—as in a 1975 photo of an elderly trio crossing a Chicago street in rhyming yellow apparel, or a 1960s photo of an imperious dog loitering beneath a pay phone—to almost ethnographic sincerity, as in her photos from a six-month solo voyage around the world in 1959. She often photographed children, particularly when they were aggrieved or lost in adultlike introspection. Above all, she made images of casual lyricism, as in her celebrated 1957 photo of a woman in white drifting through a dark Florida night. Maier’s are the kinds of photos about which you can only say: These are the real deal.

The fact that Maier was dead by the time she became famous has proved a boon for her posthumous renown; in her absence, the mysteries around the photographer-nanny became irresistible hooks for editors and curators. Maloof has been entrepreneurial about marketing her story. At least half a dozen monographs have appeared in the last decade, bolstered by numerous exhibitions and a steady chorus of press. In 2015, Finding Vivian Maier, a documentary that Maloof co-directed, was nominated for an Oscar and burnished Maier’s legend further. If she’s not quite in the canon yet, she’s certainly wait-listed.

Maier has also been the subject of two notable biographies. The first, Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife, by Pamela Bannos, was released in 2016. The second, Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny, by Ann Marks, exemplifies the allure and risks of writing about the enigmatic Maier. Marks, a former marketing executive at Dow Jones, began to dig into Maier’s life after watching Maloof’s film. She kicks off her biography with a brassy sales pitch: “By book’s end, key questions will be answered, including the one everyone asks: ‘Who was Vivian Maier, and why didn’t she share her photographs?’ Mystery solved.”

Well, maybe, maybe not. Treating Maier like a riddle makes for good jacket copy but can also turn her into a kind of Rorschach: One sees in her whatever the critical mode du jour demands. Circa 2011, she was “the best street photographer you’ve never heard of,” to quote Mother Jones. Today, she is an aerosol of neuroses and quirks, the lonely spinster who shampooed with vinegar and slathered Vaseline on her face; who wore men’s size 12 shoes; who dumped drippings from a roast pan into a glass and drank them. As Marks describes Maier’s eccentricities, she starts to play the amateur clinician, marshaling hypotheses from medical experts whose secondhand diagnoses foreground a story of trauma and unwitting victimhood. Commercial publishers require a takeaway, and so Maier becomes here something she would have detested: an inspiration.

Maier is a tricky subject for a biographer. She spent the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s as a nanny, shuttling between families, or sometimes enjoying the reprieve of stable employment. (Her longest post was 11 years.) Whenever she moved, she locked her room and forbade anyone from entering. She seems not to have had romantic relationships, and had few personal ties. She left behind little by way of diaries or letters. Marks bases part of her portrait of Maier on the recollections of people who knew her glancingly, who remember her as an “extraterrestrial” figure. “She was … a very foreign presence in Highland Park,” recalls a friend of the Gensburgs, the family that employed Maier the longest. Marks’s physical rundown suggests why:

[Maier] dressed formally; her everyday attire consisted of a tailored suit or crisp Peter Pan–collared blouse paired with a calf-length skirt. She still wore old-fashioned rolled-down stockings, unable to make the transition to pantyhose. It was all covered up with oversize men’s coats in beiges and grays and topped with a trademark floppy hat.

Adding to the sense of foreignness was Maier’s brusqueness and penchant for French expressions. She presented a stern image that seemed at odds with the sensibility of her photos: The strict disciplinarian who insisted that her young charges address her as “Mademoiselle” and who sometimes slapped the children in her care also created a portfolio rife with humor and tenderness. More puzzling still, the woman who once traveled the world alone, who frankly espoused her opinions, and who seethed with ambition spent most of her adult life in the suburbs, anonymously plying her art. Marks begins her book with an epigraph of dichotomous terms acquaintances used to describe Maier, among them: Caring/Cold, Feminine/Masculine, Jovial/Cynical, Passionate/Frigid, Social/Solitary, Mary Poppins/Wicked Witch.

Despite her outward formality, a streak of playfulness runs through her photographs. In her more than 600 self-portraits, she finds ingenious ways to use mirrors and storefront windows to reflect her plain intensity, or else manifests as a kind of negative presence, as in more oblique shots of her shadow against sidewalks and walls. A self-portrait from the 1970s depicts her shadow against a laborer’s mud-spattered behind; another shows her shadow hovering amid a patch of buttercups (an image later used on a dress displayed in Bergdorf Goodman’s storefront). Other self-portraits are more direct: Maier reflected in a car mirror, her face neutral, aloof. According to Marks, Maier almost never let anyone else take her picture. How are we to understand these paradoxes?

In Marks’s telling, Maier inherited a split sense of self. Maier’s mother, Marie Jaussaud, was born in France in 1897, the illegitimate daughter of a teenage fling. “The baby girl was welcomed into a world where she officially didn’t exist,” Marks writes, noting that this shame “set into motion three generations of family dysfunction.” By 1919, Marie had immigrated to New York City, where she married an alcoholic steam engineer named Charles Maier. The couple gave birth to a son, Carl, in 1920, and to a daughter, Vivian, in 1926. The Maiers’ marriage was unhappy, and in 1932 Marie and Vivian fled to France, leaving young Carl behind. Mother and daughter returned to New York in 1938, where Maier eventually lodged with a widowed family friend, and found work in a doll factory (perhaps accounting for some later shots of dolls discarded in trash cans).

In 1950, Maier again returned to France. It was there she began taking photographs with a box camera: panoramas of the Alps, studies of the region’s working class, portraits of family. “It is clear from her early negatives and prints that Vivian possessed a great deal of confidence,” Marks writes. “She typically covered her subjects with just one shot, an approach that would become a trademark.” In the spring of 1951, Maier returned to New York, where she continued shooting, and even flirted with the idea of launching a picture postcard business. Most importantly, Maier revolutionized her practice by purchasing a Rolleiflex camera, which allowed her to literally shoot from the hip.

Marie almost entirely disappears from the biography after this point. “[She] stands out as disturbed and mentally unstable, even among a group of troubled individuals,” Marks writes of Maier’s mother. A doctor who examined the family records for this biography suggests that Marie had narcissistic personality disorder. She rarely held a steady job and was allergic to housework. She fabricated medical ailments, and in a letter to an officer about Carl’s care, she strikes a paranoid tone, lamenting that everyone had “plotted against” her. Although Marks acknowledges that it’s impossible to accurately diagnose Marie, this doesn’t stop her from premising the whole biography on such drive-by psychologizing. Indeed, the book is a case study for what responsible biographers shouldn’t do.

Some of Marks’s theories are more credible than others. It’s likely, for example, that Maier was a hoarder. By the time she died, she had crammed more than eight tons of possessions into storage lockers. (Her hoarding cost her at least one nanny job.) At other times, though, Marks’s hypotheses are purely speculative. “Physical and sexual abuse can contribute to trauma,” she writes, “and Vivian’s behavior suggests that she may have endured this type of exploitation.” The behavior in question—Maier’s distaste for physical intimacy, her fusty wardrobe, and her cautioning young girls against sitting on men’s laps—doesn’t strike me as compelling evidence of childhood sexual abuse so much as the traits of a reserved woman with old-fashioned notions of propriety. “[Maier’s] brother was definitively diagnosed with schizophrenia, and her mother almost certainly had a history of some sort of mental illness,” Marks writes. “Many felt Vivian’s grandfather Nicolas Baille may have also, based on his antisocial behavior and extreme paranoia.” (Marks doesn’t specify whom she means by “Many.”) She asks the same doctor who diagnosed Maier’s mother to take a crack at Maier herself. The verdict: Maier was perhaps a “classic case of schizoid disorder.”

Marks uses the fact of Carl Maier’s schizophrenia to prop up this diagnosis. One of the assets of her largely lackluster biography is the gumshoe work she does chasing down Carl’s records and filling in his story. (The book’s multiple appendixes, including one devoted to “genealogical tips,” suggests that building out a family tree is Marks’s real passion.) Carl was imprisoned at age 16 for tampering with the mail and forging a check. He joined the military but was dishonorably discharged for a drug-related offense. He bounced in and out of psychiatric hospitals as an adult and died of an aortic thrombosis at a rest home in 1977, at age 57. He and Maier had little contact with each other, although Marks portrays them as heirs to a common bloodline of mental illness. Marks takes Carl’s diagnosis at face value, despite how often the label schizophrenia was slapped onto criminalized bodies at mid-century, particularly among institutionalized drug users. Still, let’s grant that Carl had some kind of genetic psychological disturbance—what does that mean for Maier?

It means that her creativity, her art, is inextricable from mental illness. That’s a generic enough argument, but in Marks’s hands, it turns cloying. Her interpretations of Maier’s work sometimes take unfortunate cues from clinical analyses. She quotes a father-son duo of Freudian therapists who posit that “the negative themes that surface in Vivian’s portfolio—including death, violent crime, demolition, and garbage—represent subconscious reflections of her low self-esteem.” Name any worthwhile photographer—any worthwhile artist—and you’ll encounter “negative themes.” This is vapid psychoanalysis and even worse critical writing.

As I read, I was increasingly irritated by this reductive and patronizing portrayal of Maier. (This is underscored by how Marks refers to Maier as “Vivian.” “I use her first name throughout because this is how most people know and speak about her,” Marks writes by way of explanation. She doesn’t consider that Maier, who worked in a service capacity all of her life, was unlikely to be addressed by her surname.) “With immense strength of character and perseverance,” Marks writes, “Vivian developed compensatory qualities and coping mechanisms, like photography, to manage her mental health issues.” In Marks’s account, Maier is a mentally ill woman who took photos almost as a therapeutic tic rather than a full-fledged artist with (perhaps) a mental illness. Maier’s self-portraits, according to Marks, are simply ways to substantiate herself in the world—signposts of a woman who was forever unmoored. Even Maier’s prolificness is evidence of a compulsion, as if her taking pictures was of a piece with her hoarding of newspapers. Marks never considers that perhaps Maier just enjoyed being a photographer, and that the act of framing a shot was itself creatively fulfilling. Would anyone point to a writer’s pile of false starts and trashed drafts as signs of a mental disorder?

Just because Maier often didn’t develop her rolls of film and rarely produced prints (and almost never exhibited them) doesn’t mean that her creative practice was somehow stunted or insular. That’s a careerist view of how a photographer should operate. Maier was undoubtedly a serious, dedicated, and consummate artist, largely self-taught, who honed her craft over decades. As Marks herself notes, Maier was more than a hobbyist, even from the beginning: “Altogether, the thousands of early images … confirm how intensely Vivian worked to master the basics of photography during her time in [France].” In New York, Maier sought out “colleagues to learn from, collaborate with, and engage in shoptalk.” She assiduously cropped images and experimented with color film. Even by the end of her career, Maier was known to leave precise instructions for the technicians entrusted with developing her images. But by pressing her into a queasy Hallmark narrative of a woman triumphing over her demons, Marks’s biography unintentionally undervalues Maier’s achievement. Photography wasn’t a “coping mechanism” but her life’s work.

“I’m sort of a spy,” Maier once told someone who asked about her profession. She was being cheeky, but the remark indicates how she saw herself: as a witness and a trespasser, a woman interested in momentary revelations of truth, no matter how painful or embarrassing or fraught. Her photographs represent a vast album of American street life across five decades, and, parallel to that, a chronicle of Maier’s own place in that landscape. It’s a body of work that’s simultaneously objective and subjective, in which Maier is both the author and a recurrent, ambiguous protagonist who lends the entire undertaking a kind of self-referential weight. Contrary to Marks’s argument, I see no meaningful distinction between the photographer and the world in Maier’s work. She doesn’t appear to me as an isolated woman trying to fix her coordinates in a universe from which she was somehow estranged. She looks, instead, like a woman who was profoundly and intuitively present.

If you read enough biographies, you realize that the genre has a fatal flaw, a system error: Every person is unknowable, not least of all to themselves. There is, in everyone, some small cinder of truth that never sees the light of day. Biographers pretend that this cinder can be revealed, and that order can be imposed upon an unruly life. That’s a lie. Ann Marks hasn’t solved the mystery of Maier—why would we want her to? The photographer’s mystery remains intact, suffusing the thousands of indelible images she left behind in those storage lockers. It’s better to look there for the truth of her life, in those pictures of the world that she put away, as if she saw, and understood, what the rest of us never would. ~ Jeremy Lybarger · Dec 21, 2021.

1 note

·

View note

Link

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

2017 Holiday Newsletter

Welcome to the 2017 Politics and Prose Holiday Newsletter. As always, we’re proud to present a selection of some of the year’s most impressive books. Happy holidays to all!

Graphics

Chris Ware’s new collection, Monograph by Chris Ware (Rizzoli), assembles countless strips, pages, magazine covers, sculptures, photographs, and other things into a thorough and astoundingly generous retrospective of the artist’s career. It comes replete with commentary written by Ware himself, who charts his path from RAW to Jimmy Corrigan to Building Stories and beyond. Reading this book is like touring the interior of a vast and seemingly impossible mechanism carved from space metal, while your tour guide chats amiably and bemoans the lack of carpets. There are also individual booklets within the book that you can flip through, and several of his New Yorker covers depicted in their full glory. For any fan of the cartoonist, this is probably the single best purchase you could make this holiday, a blueprint for everything Ware has done over the past few decades. But for artists, this is something even better: Chris Ware opens the door backstage, shows you how he performs the magic tricks, and then gives you a chance to do it yourself. - Adam W.

Art and Artists

The Art Museum, by the editors of Phaidon Press, brings together an astonishing cross-section of work from around the globe and throughout time, reproduced in over 1,600 beautiful color images. The reader can jump from virtual room to virtual room by flipping the pages, or stay in one place for a comprehensive study. This book is perfect for an art lover, a person who wants to learn about art, or someone who loves art but whose feet just can’t take the Smithsonian anymore. A single book doesn’t get more entertaining or informative than this, and finally there is no crowd standing in front of what you want to see. - Bill L.

Women Artists in Paris: 1850-1900 (@yalepress) edited by Laurence Madeline, former curator at the Musée d’Orsay, is a must-own for art lovers, historians, and feminists alike. This stunning exhibition catalogue presents over eighty paintings by thirty-seven different artists. Paris in the late nineteenth century was considered the place for artists to train, and people came from around the world to develop their technique. This catalogue is a testament to the exceptional and varied work produced by the women who journeyed to Paris to pursue their artistic ambitions. These artists fought to achieve recognition at a time when artistic talent and creative genius were thought to be reserved for men, all the while also trying to adhere to the social norms that governed the lives of respectable women. They persevered in the face of rejection and condescension, and created masterful works of art in the process. The scholarly essays that open the book are fascinating and well worth the read, but the catalog of full-page color reproductions that follow are what readers will find irresistible. Here you will encounter works by household names like Mary Cassatt alongside those by artists still waiting to achieve the widespread public recognition they are due, such as Marie Bashkirtseff and Cecilia Beaux. - Alexis J. M.

Projects (@abramsbooks) chronicles forty-four Andy Goldsworthy installations around the world, as they change and evolve with their environments. This book, a companion volume to Goldsworthy’s Ephemeral Works, includes stunning photographs, site maps, and an extensive interview. You’ll find his usual cones and labyrinths made of wood and stone, but unlike his “ephemeral” works, whose construction marked an endpoint, these pieces began life only when Goldsworthy finished them, for they evolve as they are weathered by the seasons. Goldsworthy documents, for example, walls covered in porcelain clay, as they dry, crack and tear away, and enormous slate chambers, enclosing wind-fallen branches, which gradually transform as moss and fungi cover them. He repaves an ancient forest track with rectangular stones and cuts a new path across an Ohio estate, always maintaining 950 feet above sea level. An igloo of woven branches sits inside a pit, accessed through a doorway via steps in a terraced wall. A flowing line of fallen cypress weaves through eucalyptus trees, which overtake a California landscape. But whatever he does in these installations, Goldsworthy invites us to experience nature freshly. This gorgeous, glossy volume will make an extraordinary gift for the art or nature lover in your life. - Amanda H.D.

Rothko: The Color Field Paintings (@chroniclebooks) is a tribute to one of the greatest periods by a single painter in art history. Mark Rothko (1903-1970), one of the leading Abstract Expressionists, pioneered the large, flat fields of solid color that Clement Greenberg dubbed “color field painting.” He worked his way toward them throughout the 1940s, and by 1949 had “arrived,” as his son, Christopher Rothko, says in the Foreword. The artist pursued color fields for the rest of his life, arranging two, three, and four color rectangles in dramatic and shimmering patterns that establish kinetic relationships between the viewer and the canvas. Presenting fifty of Rothko’s iconic paintings in chronological order, this book allows you to watch the artist develop his style and discover what the colors and rectangles could do; you can see the shades deepen, and darken. The volume also allows you to savor the full, luminous power of each composition, giving you the images one by one, with plenty of white space for the colors to breathe. Janet Bishop, curator of painting and sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, provides a commentary on Rothko’s legacy. - Bennard F.

Alexander Calder (1898-1976) was the son and grandson of sculptors, but when he went to school he studied engineering. Later, committing himself to art, he chose painting, like his mother. It took a few years before he accepted his fate and turned to sculpture. This brief period of indecision is the single moment of angst in the life of one of the twentieth century’s most joyful and original modern artists. Inheriting his father’s dexterity as well as his “playful, lively, fantastic” tendencies, Calder (Knopf) dedicated his life to animating the inanimate. In Jed Perl’s lively, affectionate, and thorough account to 1940, Calder’s life was pretty much on track from the start. With the avant-garde “always part” of it, he grew up in the artistic circles of both France and the U.S., a peripatetic life he continued. He was an incorrigible punster (see his work A Merry Can Ballet) and everything he did was infused with humor. Perl traces Calder’s jeux d’esprit from the early portraits and objects he made by bending wire, works that “suggested rapidly executed line drawings leaping into the third dimension,” to the elaborate Cirque Calder that was meant to be performed, not just looked at, and on to his abstractions, which were also a “menagerie…of unexpected forms” in motion, and which Perl, in the spirit of his subject, describes as “motions galumphing, jagged, swishy, swirly.” As playful as they were serious, these mobiles (named by Duchamp) and stabiles (so-called by Jean Arp) revolutionized sculpture, taking a stationary form, making it move, and creating new relationships between the viewer and the art. Perl is tireless in tracing Calder’s influences, which included Miró, Klee, Hélion, Saul Steinberg, Mondrian, Edgar Varèse, Martha Graham, and Malcolm Cowley. All were his friends, and Perl’s engaging, scholarly, and buoyant biography—and its 400-plus photos—makes it easy to see why. - Laurie G.

Among the few things known about Vivian Maier: she was a great photographer. She worked as a nanny. She was born in New York, lived in France from age six to twelve, grew up in a splintered family, spent the last fifty years of her life in Chicago, and left tens of thousands of photos, negatives, slides, and undeveloped rolls of film in storage. Once these surfaced after being auctioned off, their new owners began the myth-making that Pamela Bannos, a professor of photography, both charts and refutes. Her Vivian Maier (Chicago) is a kind of Emily Dickinson of photography; while she roamed the streets relentlessly, she let no one in. Her neighbors thought she was homeless because she spent so much time on a park bench. In lieu of friends to interview, Bannos turned to the photos for clues to Maier’s life. She has studied seemingly every image Maier recorded, and follows in her footsteps from Maier’s first forays with a camera in the early 1950s, in France, through her development as a prodigious street photographer in New York and Chicago, and her travels through Europe, South America, and Asia. Looking at what Maier looked at, Bannos reads these images beautifully, giving insight about Maier’s brilliant sense of composition, her experiments, and her ever-evolving technique. She identifies the cameras Maier used, points out angles, notes lighting and shadows, and traces recurrent themes. She brings the pictures to life so vividly, and is so convincing about what was in Maier’s mind at the moment she framed each shot, that this eloquent photographic interpretation itself becomes a masterful biography of Maier not as an eccentric but as a true artist and an uncommonly independent woman. - Laurie G.

Vermeer Diptych

The ne plus ultra of Vermeer art books, Vermeer in Detail (@abramsbooks) is a conclusive cataloguing of all thirty-two paintings by the master, accompanied by 170 extremely intimate—often full page—magnifications. Satisfyingly, in this one volume is everything the eye can take in from a Vermeer painting, elucidated by a thorough presentation of all the documentation and research we do have about the dismayingly mysterious, historically unreachable Johannes Vermeer. And yet this canonical volume’s greatest asset is the lightness with which author Gary Schwartz wears his learning. An American art historian residing in the Netherlands, Schwartz delivers prose unencumbered by any scholastic staidness or over-certainty, taking an intelligent but lightsome tone wholly befitting Vermeer’s oeuvre (“Dear Reader: it’s every Vermeer scholar for himself on this one,” he avers at one point). The manner in which Schwartz groups his chosen details into chapters is itself a revelation, providing fascinating insight into life in 17th- century Delft, as well as into Vermeer’s technical genius, yet nowhere detracting from the sheer awe of viewing the Old Master at such microscopic proximity. - Lila S.

A fascinating exercise and assay, Traces of Vermeer (@oupacademic) serves as an elucidating technical accompaniment to the broader scope of Vermeer in Detail. Jane Jelley is, first and foremost, a painter. But she has become something of a reconstructive art historian through her engagement with Vermeer and his artistic process. Vermeer’s startling command of light, the snapshot-like quality of his 17th century masterworks, has long baffled even his greatest admirers. It would seem he used a camera obscura as an optic aide, but how exactly Vermeer might have used it—and whether its use in some way detracts from his genius—has been highly controversial. Jelley brings a vast knowledge, and, more importantly, practice, of traditional painting techniques to this discussion: grinding one’s own pigment, preparing canvases, long apprenticeships, third glazes. Through trials in the studio, she proposes a novel suggestion as to how exactly Vermeer could have used a camera obscura lens to arrive at his compositions, plot them onto canvas, and then prepare and layer paint to create his unparalleled works. The process, she maintains, would only further elevate Vermeer’s genius. Jelley’s engaging prose is a boon to both scholars and casual art appreciators. - Lila S.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In this scholarly but accessible exploration of the life of outsider Chicago photographer Vivian Maier, Northwestern photography professor Pamela Bannos sheds some much needed light on the elusive and misunderstood Maier. Rigorously researched and beautifully written, this is the bio that Maier deserves! 🙌🏽📸 #vivianmaier #unabridgedbookoftheweek #pamelabannos (at Unabridged Bookstore)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you @johns-prince for tagging me!!! 💛

rules: tag 9 people you’d like to get to know better

top 3 ships:

I'm not really huge into shipping, it's just not something that happens with my interests much (and yes y'all know John and Paul, so I'll include other ones) but:

Bubbline (Princess Bubblegum and Marceline, Adventure Time)

Caejose (Caeser and Joseph, JoJo's Bizarre Adventure Part 2)

Cyreese (Cyrus and Reese, Animal Crossing, is this a valid ship or nah, I just think they're cute and pure)

lipstick or chapstick: chapstick! ✨

last song: On the Wings of a Nightingale - Paul McCartney (his demo of it) but ALSO I listened to the entire EP: Motorcycle.jpg by Slaughter Beach, Dog... I am so in love with it. (And I've also been listening to Garth Brooks??? Suddenly I'm on a country kick too???) I listen to a lot of music. 😅

last movie: A Hard Day's Night (which I've seen before obv) but new movies? There Will Be Blood, Julie & Julia, and The Master. I also watch a lot of movies.

reading: The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka (it's not that long and I'm almost finished), next I'm reading Vivian Maier: A Photographer's Life and Afterlife by Pamela Bannos.

I'm not tagging a lot of people because @johns-prince tagged so many I would have. So I tag:

@princessleiaqueen @macca-bby @ya-boi-fab @stonedlennon for now :>

Tagged by @towerhaze, hullo!

rules: tag 9 people you’d like to get to know better

top 3 ships:

Oh this changes all the time lol

McLennon [John x Paul]

Sonamy [Sonic x Amy]

Inukag [Inuyasha x Kagome]

lipstick or chapstick: Uh, both? Depends on the day and the mood and how chapped my lips are lol

last song: Doja Cat - Say So

last movie: Meet Me in St. Louis

reading: A Spaniard in The Works [John Lennon]

Tagged or not, go ahead if you’d like !

@novakflower @maclen100 @those-four-goofballs @femininehygieneproducts @rhapsodywentz @fingersfallingupwards @e-writes-something @im-you-but-weaker @hide-your-bugs-away @martianmadness66 @johnericlennon @johnrlennon @weall-love-ina-yellow-submarine @leviathanlennon

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS WEEK on the GWA Podcast, we interview author, artist, writer, and academic, Pamela L Bannos on the very private yet supremely inquisitive street photographer who spent her days working as a nanny, VIVIAN MAIER!!

Maier (1926–2009) was street photographer who has been compared to the likes of Helen Levitt or Diane Arbus. But here’s the thing: despite taking pictures incessantly and amassing more than 100,000 negatives, she never published or exhibited her work in her lifetime. This is one of the most fascinating stories in art history.

Maier’s photographs reveal a woman who had empathy for her subjects – from children to the elderly – and who were often unaware of her presence. She famously worked with a Rolliflex camera which she would use for several decades, allowing for her signature square format, but which didn’t need to be brought up to one’s eye – enhancing even further how she could catch her subjects off guard. When asked about her occupation by a man she once knew, she’d say “I’m sort of a spy… I’m the mystery woman.”

Tracing the people, politics, and landscape of mid to late 20th century North America, Maier’s extensive oeuvre recorded life as it passed her by. And here’s the thing, because she never exhibited or published her work during her lifetime, she was predominantly known for her primary role as a nanny to children in the Chicago area. So much remains to be missing, which is why I can’t wait to speak to Pamela, who has looked at tens of thousands of these images; traced Maier’s footsteps from the US to France, and delved into the archive in search of everything we might know about the photographer.

Pamela Bannos is a professor at Northwestern University, and the author of Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife, 2017: http://vivianmaierproject.com/. Here is the TV interview of her discussing the book 10 min: https://news.wttw.com/2017/10/19/new-book-focuses-life-work-mysterious-photographer-vivian-maier

#Vivian Maier#Pamela Bannos#The Great Women Artists#podcast#podcasts#women in art history#women in art#outsider art#art#artists#women artists#photographer#photography#20th century art#20th century

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vivian Maier, Through a Clearer Lens

Vivian Maier, Through a Clearer Lens

But stories — like snapshots — are shaped by people, and for particular purposes. There’s always an angle. A new biography, “Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife,” by Pamela Bannos, strives to rescue Maier all over again, this time from the men who promulgated the Maier myth and profited off her work; chiefly Maloof, who controlled her copyright for a time. After a legal battle —…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Vivijan Majer: stvaralačka ličnost naspram persone

— Piše: Jovan Jona Pavlović

U Njujorku je okončana retrospektiva radova gospođice Vivijan Majer (Vivian Maier, 1926-2009) pod nazivom “Unseen Work”. Izložba je primala posetioce od 31. maja do 29. septembra 2024. godine u muzeju "Fotografiska New York". Postavka je obuhvatala oko 230 radova koji pokrivaju period od ranih 1950-ih do kasnih 1990-ih, uključujući mnoge do sada neviđene fotografije.

Izložba se fokusira na jedinstven stil gospođice Majer i njenu superiornu sposobnost da svakodnevne trenutke „uhvati“ izuzetnim umetničkim okom. Retrospektiva je deo napora da se rad predstavi široj javnosti, imajući u vidu da je njen opus otkriven posthumno, a već se smatra jednim od najvažnijih doprinosa istoriji fotografije 20. veka.

Izložba je organizovana u saradnji sa reprezentativnim ustanovama kulture John Maloof Collection iz Čikaga i Howard Greenberg Gallery iz Njujorka, i deo je međunarodne turneje koja je započela u Parizu 2021. godine.

U proteklih 15-tak godina, otkako je njen rad otkriven i publikovan, fascinantna životna priča gospođice Majer u žiži je interesovanja međunarodne umetničke javnosti. Zašto?

Gospođica Majer bila je američka ulična fotografkinja francuskog porekla. Rođena je 1926. godine u Njujorku, a veći deo života provela je radeći kao dadilja u Čikagu. Tokom slobodnog vremena ili šetnji sa štićenicima, gospođica Majer strastveno je fotografisala svakodnevni život na ulicama metropola, beležeći autentične trenutke urbane stvarnosti.

Iako je tokom života ostala anonimna, njen opus, koji obuhvata preko 150.000 negativa, otkriven je 2007. godine kada je gospodin Džon Maluf otkupio na aukciji većinu njene umetničke zaostavštine.

Opčinjen otkrićem, promovišući fotografije na koje je naišao slučajno, gospodin Maluf je producirao dokumentarni film „Finding Vivian Maier“, nominovan 2013. godine za Oskara. Interesovanje za njen nesvakidašnji život i rad otada ne jenjava. Nakon višegodišnjih istraživanja, publikovane su i dve reprezentativne biografije: „Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife“ (Pamela Bannos) objavljena je 2017. godine, a „Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny“ (Ann Marks) objavljena je 2021. godine.

U svom znamenitom delu “O slobodi” Džon Stjuart Mil nas podseća: “Među ljudskim delima, čijem se usavršavanju i ulepšavanju s pravom posvećuje ljudski život, svakako je najvažnije delo sam čovek.” Zapažanje s punim pravom može da se primeni na život i delo gospođice Vivijan Majer.

An Morin (Anne Morin), kustoskinja izložbe “Vivijan Majer: fotografsko otkrovenje” koja je prikazana širom Evrope, tvrdi da je gospođica Majer „jedna od najboljih uličnih fotografa ikada”. „Njena životna priča zaista je neverovatna, ali naporno radim kako bih je odvojila od fizičke stvarnosti fotografija.” (Morin, citirano prema Kasper, 2014) [1] Bez sumnje u iskrenost namere, plašim se da su slična nastojanja uzaludna, jer je najvažnije ostvarenje gospođice Majer upravo njena nesvakidašnja životna storija. Umetnost fotografije predstavlja okosnicu te pripovesti. Ona je jednoj neupadljivoj ljudskoj sudbini podarila smisao. To je najviše što je umetnost u stanju da pruži kreatoru.

“Kada smo obuzeti stvaranjem, osećamo da živimo ispunjenije” [2], primećuje profesor Mihalj Čiksentmihalj (Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi), i dodaje “Čak i bez uspeha (društvenog priznanja), kreativne osobe pronalaze zadovoljstvo u dobro obavljenom poslu”. Ne zaboravimo da odvojenost od umetnosti za umetnika predstavlja mučenje. Svojevrsno silovanje besmislom postojanja. Kada se fotografska šetnja gospođice Majer okonča uspešno, dnevne obaveze dadilje postaju manje zamorne i uzaludne. Zaduženja koja svet nameće mogu se u tom slučaju smatrati neophodnim pripremama za narednu rundu stvaranja. Razuman sporazum.

Profesor Čiksentmihalj još jednostavno primećuje da niko ne može istovremeno biti izuzetan i normalan. Stoga je gospođica Majer u svrhu opstanka efikasno razdvojila ove dve tvorevine. Kreativan kompromis. Za sopstveno okruženje, uljučujući tu i članove porodica u kojima je služila, gospođica Majer predstavlja neudatu, ali ponosnu modernu ženu, nebično zainteresovanu za različite aspekte savremenog života. „Lični opisi ljudi koji su poznavali Vivijan veoma su slični. Bila je ekscentrična, snažna, veoma izraženih stavova, izuzetno intelektualna i intenzivno povučena. Nosila je veliki šešir, dugačku haljinu, vuneni kaput i muške cipele, i hodala je odlučnim korakom.“ [3]

Dobro obaveštena, sa neskrivenom empatijom prema potlačenima, pokušava da svojim štićenicima savesno prenese i spoznaje koje često nisu ugodne. Zajedničke šetnje obuhvataju posete delovima grada sa siromašnim stanovništvom, ali i otvorene razgovore o različitim aktuelnom pitanjima. Audio zabeleške pojedinih dijaloga u formi intervjua pronađene su u zaostavštini umetnice. O sličnim nastojanjima svedoči i izjava gospođe Nensi Genzburg iz Hajlend Parka, čija je čak tri sina (Džon, Lejn, i Metju) gospođica Majer čuvala: „Želela je da budu veoma svesni onoga što se događa u svetu.“ [4]

Ličnost umetnice u startu se uveliko prepliće sa personom vaspitačice koja materijalno podržava obe. Neobična dadilja se kako-tako snalazi u svakodnevici. Dihotomija još nije jasno izražena. Čini se čak da će u srećnom spoju kreativna ličnost zauzvrat obogatiti život i profesionalni nastup guvernante. Fotografkinja pribavlja neku vrstu dopuštenja da posveti dragoceno vreme, energiju i finansije projektu koji je, u najmanju ruku, upitan po profesionalni opstanak vaspitačice. Uvek u potrazi za znanjem i novim intelektualnim izazovima, umetnica pristupa svom pozivu predano i naizgled nepristrasno. „Fotografisala je političare tokom kampanja (Ajzenhauera, Kenedija, Niksona, Lindona Džonsona); poznate ličnosti na premijerama ili u svakodnevnom životu (Frenk Sinatra, Džon Vejn, Greta Garbo, Odri Hepbern); radnike i putnike; pijance, kriminalce i beskućnike; urbane posmatrače [*] i žene s besprekornom frizurom u bundama.“ [5]

Početni entuzijazam doima se kao dobro odmeren i jasno usmeren. Izdržavanje koje gospođica Majer uspeva da obezbedi izborom profesionalnog poziva guvernante, po svemu sudeći podupire i skromno porodično nasledstvo. Deluje da resursi za podršku stvaralačkoj iskri nisu oskudni, naprotiv. Obilato koristi prilike za obuhvatna putovanja tokom kojih dalje širi duhovne horizonte. Ove odiseje odudaraju od navika inače sasvim skromne dadilje. „Njene kulturne potrebe vodile su je širom sveta. Do sada znamo za putovanja u Kanadu 1951. i 1955. godine, u Južnu Ameriku 1957. godine, zatim u Evropu, na Bliski istok i u Aziju 1959. godine, na Floridu 1960. godine, a 1965. godine putovala je na Karibe, i tako dalje. Vredno je pomenuti da je uvek putovala sama i da su je često privlačili siromašniji slojevi društva.“ [3] Porodice poslodavaca uglavom blagonaklono gledaju na slične ispade svoje mlade, neudate, i svojeglave dadilje. „’Ako je želela da putuje, jednostavno bi ustala i otišla’, seća se Nensi. Porodica bi angažovala privremenu zamenu dok je Majer bila odsutna; nikada nije govorila kuda ide.“ [4]

Na svojim kreativnim ekspedicijama diljem globusa, gospođica Majer neumorno fotografiše. Najverovatnije se upravo u ovom periodu intenzivnih putovanja i stvaralačke slobode formira snažna umetnička ličnost. Poriv ka nesputanom kretanju i samostalnom izboru poziva snažno je prisutan i nakon povratka u ulogu vaspitačice. Porodice za koje je radila naslućuju promenu u pristupu svakodnevnim obavezama; nažalost, ona druga gospođica Majer – osetljiva, originalna, i pre svega produktivna – postaje nedostupna i za najbliže. „’Ona zapravo uopšte nije bila zainteresovana za to da bude dadilja,’ kaže Nensi Genzburg. ’Ali nije znala kako da radi bilo šta drugo.’“ [4] Drugi deo tvrđenja danas zvuči neistinito i grubo. Većina kreativnih ličnosti koje se nisu ostvarile na sceni svog doba suočava se sa sličnim predrasudama. U slučaju gospođice Majer, pitamo se u kojoj meri upravo sam umetnik snosi krivicu za skrivanje postignuća od očiju javnosti.

Na osnovu relativno šturih dokaza koji su trenutno dostupni, izvodimo zaključak da je tokom ranijeg perioda stvaralaštvo gospođice Majer daleko vidljivije i pristupačnije, barem za osobe iz njene neposredne okoline. „Jedna porodica u Njujorku poseduje stotine starih fotografija gospođice Majer. U Čikagu bi poklanjala najviše dve. Dakle, u Njujorku je sa svojim fotografijama postupala galantnije i otvorenije.“ (Marks, citirano prema Rid, 2021) [6]

Evidentno je da pritisak svakodnevice sa prolaskom godina postaje jači. Kreativna ličnost se povremeno povlači, a umetnica često čini ustupke. Na primer, kada je stvaralački postupak u pitanju, postepeno je odustala od postprodukcije. Selekcija i naknadna obrada fotografija, štampanje reprodukcija, čak i razvijanje negativa postali su postupno nedostupan komfor. “Godine 1956, kada se gospođica Majer preselila iz Njujorka u Čikago, uživala je u luksuzu privatnog kupatila koje je preuredila u tamnu komoru, što joj je omogućilo da obrađuje svoje fotografije i razvija crno-bele filmove.” [3] Ova pogodnost omogućila je proširenu kontrolu nad kreativnim procesom – od snimanja do razvoja slika. Inicijativa iskazana preuređenjem kupatila, i odricanjem od lične udobnosti govori o visokoj zainteresovanosti za pristup resursima oskudnim za umetnicu u društvenoj ulozi dadilje. Gospođica Majer konstantno je pokazivala nesumnjivu posvećenost učenju, razvijanju umetničkog postupka, i usavršavanju tehnike. Nije to samo puko istraživanje sopstvene vizije sveta kroz objektiv, već iskreno nastojanje da se ta vizija realizuje, materijalizuje i naposletku prikaže ljudima iz okruženja.

O ozbiljnosti namere da bavljenje fotografijom obezbedi i deo prihoda, govori činjenica da je izvestan broj dela tokom postprodukcije pripreman za prodaju. " ’Ako ste želeli fotografiju,’ kaže Nensi, ’morali ste da je kupite.’ Ali gospođica Majer nije prodavala svoje fotografije radi zarade. ’Neko je morao želeti fotografiju više nego što je ona bila spremna da je se odrekne. To je poput slikara koji ne može da se rastane od dovršenog platna. Volela je sve što je stvorila.’ " [4] Sumnjam da je paralela sa slikarom adekvatna. Znamo da fotografije mogu da se reprodukuju proizvoljan broj puta. Iz sličnog razloga vizuelni umetnici kreiraju grafičke radove. Svaka grafika je autentična jer poseduje potpis autora i jedinstven serijski broj iz ograničene količine štampanih dela. Sva je prilika da iza prividne nespretnosti u prodaji stoje drugačiji motivi. Moguće je da gospođica Majer još nije spremna za ovakav oblik trgovine – bez zvaničnog zastupnika, galerije ili agenta, koji bi adekvatno procenili specifičnu vrednost. Ako je tako, možda je još uvek očekivala pogodnu priliku da se svetu obznani „na pravi način“. Možda vrednost koju nastoji da postigne kod savremenika nije finansijske prirode? Svesna je svojih kvaliteta. Nedostaje joj uvažavanje.

Nažalost, radni uslovi tokom kasnijeg perioda, nisu tako povoljni. “Dok se selila iz jedne porodice u drugu, njeni nerazvijeni i neodštampani radovi počeli su da se gomilaju.” [3] Stvaralački postupak je okrnjen. Iz ovog perioda potiče stereotip o umetniku koji stvara iz unutrašnje potrebe, bez jasne namere da fotografije podeli sa svetom. Ova složena dinamika, između posvećenosti umetnosti i zapostavljanja rezultata, kreira popularan narativ o bogatom i samodovoljnom unutrašnjem svetu gospođice Majer. “Sofi Rajt, direktorka muzeja u Njujorku, izjavila je za CNN: ’Nema publike na umu.’ Nema dokaza da je gospođica Majer brinula o svojim gledaocima – niti da je ikada zamišljala da će ih uopšte imati.“ (Rajt, citirano prema Veksler, 2024) [7]

Profesor Čiksentmihalj nas podseća i da su kreativne osobe uglavnom pametne, ali istovremeno i veoma naivne. Sva je prilika da su prefinjene kulturne navike koje je razvila igrale odlučujuću ulogu u oblikovanju i zaštiti njene kreativne ličnosti. Međutim, pomenute potrebe takođe su kreirale jasnu razliku između umetničkog identiteta i socijalne persone. Ova podela ostavila je ranjivu kreativnu pojavu nehotično bez razumevanja i podrške „običnog“ sveta. „Jednom sam je video kako fotografiše unutrašnjost kante za smeće,“ rekao je za Čikago magazin voditelj tok šoua Fil Donahju, koji je gospođicu Majer zapošljavao kao dadilju manje od godinu dana. „Nikada nisam ni pomislio da to što radi može imati neku posebnu umetničku vrednost.“ (Donahju, citirano prema Veksler, 2024) [7]

Kakogod, gospođica Majer ni ljudima ni okolnostima nije dozvolila da joj oduzmu inicijalnu stvaralačku iskru i autentični “raison d'être”. Granica je jasno povučena na tom frontu. „Njen odnos sa svetom odvijao se kroz kameru, kroz proces fotografisanja/snimanja okruženja.“ komentariše An Morin, i dodaje ”Ali, kada bi okončala snimanje, nije pokazivala isto interesovanje za rezultate.” (Morin, citirano prema Kasper, 2014) [1]

Istina je da nikada nećemo doznati koliko su bolni bili ustupci načinjeni realnosti. Da li je za gospođicu Majer sam čin fotografisanja bio dovoljan? Da li je zaista mogla da bira? Ili su izbor u njeno ime načinile društvene i ekonomske okolnosti, kao i marginalizovani položaj? Dok je pažljivo posmatrala svet, njene radove nakon snimanja nije video niko. Čak ni autor.

Izgleda da je prelaz na fotografiju u boji konačno označio tiho gašenje plana o izlasku na umetničku scenu, ukoliko je slična namera ikada i postojala. „Njene kolor fotografije fokusiraju se na muzikalnost slike, oblike, i intenzitet boja. Kada je snimala u koloru, zaista je koristila medij boje u punom smislu. U njenim crno-belim radovima, pažnja je više usmerena na subjekte, na ljude koji su prikazani.” (Morin, citirano prema Kasper, 2014) [1]

Tokom ovog kasnog perioda, lica postupno nestaju sa fotografija, a izranjaju apstraktne kompozicije živog kolorita. Njihova umetnička vrednost nije umanjena, ali je izmenjen senzibilitet. Ukoliko nije uspela da se poveže sa savremenicima vešto hvatajući njihove portrete u prizorima iz svakodnevnog, svima bliskog života – ta šansa svakako je umanjena preovlađujućim izborom novih motiva. U užurbanom gradskom okruženju, tema ima mnogo, a gospođica Majer svakoj posvećuje dužnu pažnju, uprkos očiglednog mimoilaženja sa popularnim ukusom. „Beležila je teksture i odbačene stvari iz urbanog okruženja: grafite, požarne stepenice, znakove, smeće, senke, napuštene novine, polusrušene zgrade. Spontano je pravila prelaz između različitih prizora.“ [5]

Naslućujemo da je između stvaralačke ličnosti i socijalne maske gospođice Majer sve vreme obitavao antagonizam, povremeno utišan srećnim sticajem okolnosti. Napokon, u jednom trenutku, na nekoj misterioznoj raskrsnici života, ove dve konstrukcije nesretno su se mimoišle. Namesto da se dopunjuju i pomažu, potom su se udaljavale. Umetnica postepeno prerasta u praktičan teret za dadilju. „Kada je razgovarala za posao kod Zalmana, profesora matematike na Univerzitetu u Čikagu, i Karen, urednice udžbenika, jasno je stavila do znanja jednu stvar: ‘Moram vam reći da dolazim sa svojim životom, a moj život je u kutijama.’ Nema problema, uzvratili su. Posedovali su prostranu garažu. ‘Nismo imali pojma šta nam se sprema,’ preneo je Zalman. ‘Došla je sa 200 kutija.’” [4]

Bez mogućnosti da kreativnu strast izvede iz senke, “normalna” dadilja Majer prinuđena je da trpi. Ponosna i nezavisna, postepeno se pred kraj života povlači u neku vrstu izabranog izgnanstva. Zavisi od dobre volje drugih. Zakup poslednjeg apartmana plaćaju tri brata o kojima se nekoć brinula, i koji su joj krajnje naklonjeni. Svoj ogroman opus taji i pred njima. Iznajmljuje ormariće za skladištenje, gde smešta enorman broj negativa i različitu fotografsku opremu, te brojne audio i video zapise. Nakon fatalne povrede glave usled pada na led, oko Božića 2008. godine, poslednje dane provodi u urgentnom centru. Trojica bivših dečaka iz Hajlend Parka svakodnevno je posećuju. Njihova majka, Neni Genzburg, ne propušta da primeti: “Zaista je bila jedinstvena osoba, ali nije imala visoko mišljenje o sebi.” [4]

Nakon što zakup ormarića nije obnovljen, umetničko zaveštanje gospođice Majer prodato je na aukciji još za života. Niko iz njenog okruženja nije o tome znao ništa. Tajna je sačuvana.

Zašto se nije poverila ljudima koji su je prigrlili? Zar bi se svet srušio? Da. Njen bi se srušio. Pažljivo zidana fasada nepovratno bi propala. Nije to dopustila ni kada se lek konačno pretvorio u otrov. Nesigurnost u autentično mesto u svetu, pohranjena možda još u detinjstvu u okvirima disfunkcionalne porodice, uzrokovala je nepoverenje i povlačenje od ljudi. Svet nije prepoznao umetnicu. Tolerisao je načitanu ali čudnu personu. Dadilji je to bilo dovoljno.

Na drugoj strani, pitamo se: da li je tokom plodnih decenija kontrolisana „šizofrenija“ između lične i javne pojave dodatno pokretala turbine bujnog i originalnog stvaranja? Da li je varničenje između čudnih polova postojanja rađalo iskru stvaralaštva? Smatram da je to izvan svake sumnje.

Umetnica i dadilja odvažno su iznele zadatak do kraja. Svetu preostaje da ih prigrli i pomiri. I da napokon sa ponosom prikaže fotografije iz neponovljive vremenske kapsule.

[1] Casper, J. (2014, July). Vivian Maier: Street photographer, revelation. LensCulture. Preuzeto sa:

https://www.lensculture.com/articles/vivian-maier-vivian-maier-street-photographer-revelation

[2] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperCollins.

[3] Maloof Collection, Ltd (n.d.). About Vivian Maier. Vivian Maier. Preuzeto sa:

https://www.vivianmaier.com/about-vivian-maier/

[4] O'Donnell, N. (2010, December 14). The life and work of street photographer Vivian Maier. Chicago Magazine. Preuzeto sa:

https://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/January-2011/Vivian-Maier-Street-Photographer/

[5] Lybarge, J. (2021, Dec 21). The Trouble With Writing About Vivian Maier. The New Republic. Preuzeto sa:

https://newrepublic.com/article/164770/vivian-maier-photographer-biography-review

[6] Reid, K. (2021, Dec 7). Writing the True Story of Vivian Maier’s Life. Chicago Magazine. Preuzeto sa:

https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/december-2021/writing-the-true-story-of-vivian-maiers-life/

[7] Wexler, E. (2024, July 9). Meet Vivian Maier, the reclusive nanny who secretly became one of the best street photographers of the 20th century. Smithsonian Magazine. Preuzeto sa:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/meet-vivian-maier-reclusive-nanny-street-photographer-20th-century-180984665/

[*] "Flâneur" je francuska reč koja se u engleskom jeziku koristi da označi osobu koja se bez cilja šeta gradom, uživa u ambijentu i opaža život oko sebe. Flâneur je često opisan kao pasivni posmatrač, koji se kreće kroz urbanu sredinu, istražujući njene detalje, atmosferu i ljude, obično u kontekstu modernog grada. Ovaj pojam se često povezuje s umetničkim i literarnim proučavanjem svakodnevnog života u urbanim sredinama.

0 notes

Link

TO MANY, Vivian Maier is known as the mysterious Chicago nanny who took photographs secretly — thousands and thousands of photographs, often left as undeveloped rolls of negatives, which she then boxed up and stored in lockers. She was perceived by the locals in her Rogers Park neighborhood as a cantankerous old bag lady who ate food out of cans. Nobody knew about her art. But in the months before she died on April 21, 2009, aged 83, her storage lockers went into arrears. The padlocks came off, and all her photos and old cameras, her stacks of newspapers, magazines, and other items, went up for blind auction. One buyer bought the whole lot, and put it up for sale again in four or five subsequent auctions, thus setting in motion the scattering of Maier’s work. Some buyers, curious about the photos they found, began posting them on the internet.

The discovery of Vivian Maier caused a sensation in the art world, and her story has captivated many. It is, after all, a tale of mystery and intrigue: a woman who works as a nanny, never marries, says almost nothing about her life and childhood, dies in obscurity, dwarfed by the belongings she hoarded, only to be unveiled as one of the boldest and most poetic street photographers of the 20th century. It is difficult not to be fascinated by the woman, who can be glimpsed in the various self-portraits she took throughout her life, casting her distinctive shadow on a pavement or a wall — the tall, austere figure with an angular face and a beguiling stare, always smartly dressed in 1950s-style skirt suits or overcoats regardless of what decade it actually was.

This is exactly the story Pamela Bannos, in the first full biography of Maier, sets out to discredit. Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife is intended as “a counterpoint, a counternarrative, and a corrective” to the narrative spun primarily by the buyers of Maier’s boxes at the auctions of August 2007, and in particular, former real estate agent John Maloof, who has done more than anyone else to make Maier visible. As one blogger put it in 2014, Maloof could be described as a man who “just found an old photo in storage, attached [his] name to it, claimed all rights and sold limited editions of that photo for thousands of dollars.” It is difficult to avoid Maloof when seeking out Maier’s photography. He has published three books of her photos and made a documentary, Finding Vivian Maier, released in 2014. When the productions are not in his name he has shown less enthusiasm however: he refused to collaborate when the BBC arrived in Chicago to make their own documentary on Maier for Alan Yentob’s Imagine series; when Bannos began working on this biography, Maloof set such high demands she found it impossible to work with him, thus denying her access to his collection.

Maloof is, undoubtedly, the archvillain in A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife, cultivating the image of the “mystery nanny photographer” and even admitting this was what kept him going. “If I knew all about her, I don’t think I’d be as interested,” he says. But he is also the figurehead of a deeper problem dogging all Maier scholarship: given that she was so secretive, and that her oeuvre has subsequently been so dispersed, can we ever build a true picture of the artist? To this, Bannos simply follows the photographs, tracing where Maier went and looking at what subjects drew her eye. Her approach is refreshing — a clear-eyed, empirical account that counters the willfully obscure, ego-driven yarns spun by the buyers. In this light, A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife is a work of real integrity in a field lacking such a genuine spirit of inquiry.

The biography proceeds by dual narratives, shifting between recounting and retracing Maier’s life, and the story of how her oeuvre was subsequently “discovered” following the auctions — Maier’s life, in other words, and the afterlife of her work, told in parallel. This jumping across time has its drawbacks for the flow of the biography. With the constant shifting from one epoch to another, we become less immersed in Maier’s life, and, perhaps as a by-product of this, Maier’s childhood in New York and France, her work as a nanny, the heyday of her photography in New York and Chicago throughout the ’50s and ’60s, and then her slow decline from the ’70s onward lack intensity. It is clear the nature of Maier’s photography evolved as the world around her changed, just as the cultural, social, and political atmosphere in the previous decades infused her work and likely influenced her behavior. But when Bannos describes this context, and offers some color and detail on the developments in art and photography, the shifts and controversies in society and politics, the prose can be clunky and dutiful — paragraphs are often tacked onto sections, as though to do the job of contextualization in a few lines, but evoked without much passion. A deftness of touch in knitting together biographical material with the historical situation is lacking.

One forgives Bannos, however, because she directs her energies on getting the counternarrative right, and this she manages admirably.

Maier’s choices to not share her history or her photography also seem vital to seeing her as a woman who did her best to control the way she was seen, as well as how she viewed and recorded her surroundings. Maier found men to be “uncouth” yet her legacy has been almost entirely in the hands of men — something we cannot ignore when considering how her life and work have been depicted.