#PA Dutch Folk Magic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hexenwolf, A Mysterious, PA Dutch Wolf-Like Entity

♦️Introduction to Hexenwolf♦️

Hexenwolf are mysterious entities which are known throughout rural Germany and Pennsylvania. Many accounts were written about them by the Pennsylvania Dutch, with some people witnessing their powerful presence firsthand. They were often a source of both fear and intrigue. Hexenwolves are entities that traverse the wilderness and rural countryside at night. They are able to project themselves here from their own realm, often via portals. People often see them appear from seemingly nowhere. Many people have had interactions with them, where the Hexenwolf would say a meaningful, often precognitive message aloud, or quietly project a message to them via thoughts. They appear as a tall, bipedal wolf, with fur colors varying. They often wear long robes or cloaks. They are nocturnal beings and they detest bright lights. They are masters of camouflage, easily able to blend in with their environment by changing color to match backgrounds. Many are able to cloak themselves and remain invisible, completely undetected. They are quiet and observant. They have an intense gaze, and they are able to project their thoughts onto others through this stare. They have raw power, and exude unusual dark energy. They are naturally drawn to dark witches, as well as other wolves. Their name is because of their strong association as friends and guardians to human witches. They may reach out and communicate telepathically to witches and occultists to offer help, support and occult guidance. They are loyal, intense, courageous, and protective, and can assist in protective magic and vengeance magic. They are dark magic beings. You may see tall shadows or energy orbs.

Talisman available at Temple Of Mars Hexerei on Etsy.

♦️WE ARE NOT AFFILIATED WITH ANY OTHER OCCULT SHOPS OR OCCULT PRACTITIONERS♦️

♦️Written descriptions and photos exclusively belong to us, Temple Of Mars Hexerei. You may not copy our item descriptions or photos for profit in any way, shape or form. We realize that our item descriptions contain interesting, rare historical and metaphysical information, therefore you are welcome to share item descriptions for strictly informational purposes only in a positive way, or strictly as a way to positively promote our shop, but when doing so, site that it comes from Temple Of Mars Hexerei. Thank you♦️

#witchcraft#magick#hexerei#occult#hexeglaawe#Spirit Companion#pa dutch folk magic#PA Dutch Magic#Heideglaawe#Temple Of Mars Hexerei

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

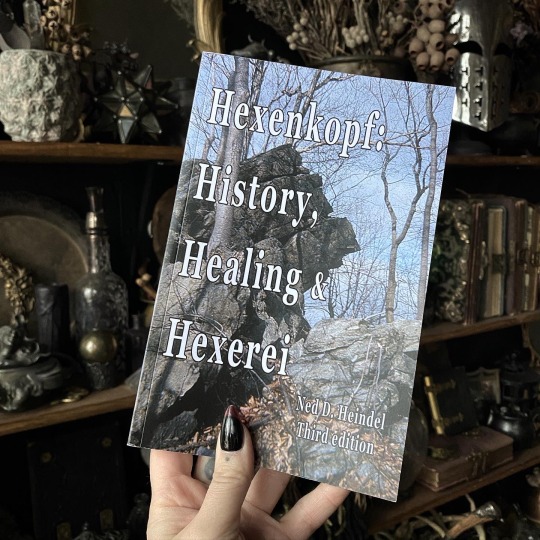

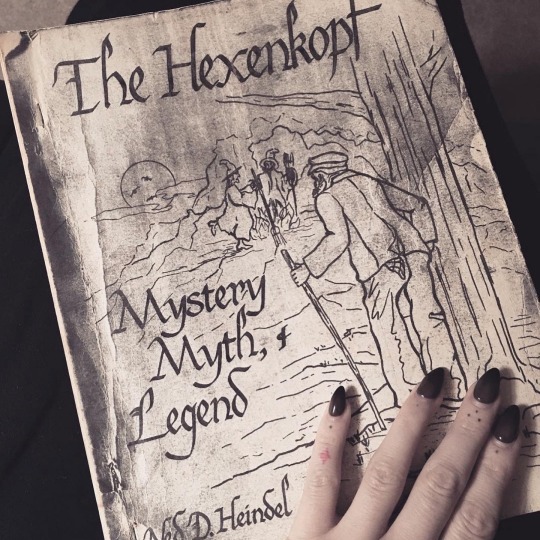

I am excited to share that my original artwork ‘Witches’ Night on Hexenkopf Rock’ is featured in the third edition of Ned D. Heindel’s ‘Hexenkopf: History, Healing, & Hexeri’! You can grab a copy for yourself from The Sigal Museum. It is an honor to be included in such a wonderful book that preserves a part of Pennsylvanian history and the history of Pennsylvanian folk magic!

In 2016, I unearthed a rare copy of the first edition of this book (published under a slightly different title in 1974, seen in the third photo) at my grandmother’s house and it is what inspired me to create ‘Witches’ Night on Hexenkopf Rock.’

The rock itself is a stony summit in Williams Township, PA that has long been associated with magic, ritual, and witchcraft. ‘Hexenkopf: History, Healing, and Hexeri’ takes an in-depth view at the history and folklore surrounding Hexenkopf Rock and examines how Braucherei, or PA German folk magic, first developed in the area and contributed to the rock’s legends. Also discussed are stories of Native American magic, witch gatherings, ominous omens, and apparitions that have helped bolster Hexenkopf rock’s mysterious reputation. I highly recommend this book if you are interested in American folk magic and Pennsylvanian lore!

#poisonappleprintshop#Hexenkopf rock#Hexenkopf#Williams township#Pennsylvania#PA#American#pennsylvanian#folk magic#braucherei#hexeri#pow wow magic#PA Dutch#PA German#Braucher#original artwork#witches night#witchcraft#Easton#history#folklore#lore#magic#ritual#art#artwork

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is this the year I finally get into braucherei??

#just dara things#dara’s witchy shit#IMO as a PA Dutch person I don’t think braucherei is a ‘real’ PA Dutch tradition#I’ve done a lot of research on the academic side and everything I’ve seen#points to it being something brought by later German immigrants (late 1800s?)#or the name just invented at that time as a label for various types of German folk magic#bc it seems our PA Dutch superstitions and practices don’t bear a whole lot of resemblance#but nonetheless I find it interesting and it’s more attractive to me than English cunningwork#which also seems cool#but I am just less drawn to it

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I recently came across your post about pennsylvania dutch folk magic being a closed practice. I obviously agree with this but I was hoping you could help me in a bit of a personal journey if you have the knowledge or know where to find it.

My family, maternally, comes from germany and immigrated to the pennsylvania dutch area. I was wondering it you knew if this blood connection to the culture would be enough to warrant looking into the culture's traditions? I spent much of my life talking to my great grandma from PA and spend as much time as possible talking to my grandma and great-aunt (her daughters) and while we discuss their culture, i believe much of our knowledge died with my great grandmother.

If you have any thoughts or advice I would love to hear them. Thank you very much 💕🌿✨

Hello there. 🌱

In all honesty, I don't feel like I'm the best authority on this. But, to me, if you have Pensylvania Dutch ancestors in living memory—especially if at least some of their traditions have been passed down to you—then it doesn't seem unreasonable to explore that some, so long as it's done steadily and respectfully. For myself, I have never felt like I was really being called to fully "embody" my Penylvania Dutch heritage, and I would never try and call myself a Braucher or anything like that, but the traditions that I did inherit are very dear to me.

If you're wanting to explore Pennsylvania Dutch traditions in a serious way, your best bet is probably seeking someone who is actually part of that tradition, and doing your best for prove yourself worthy of learning some from them. Of course, there's no guarantee that someone would be willing to share with a person from outside of their direct community.

Best of luck moving forward!

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

So a while back (and I mean a *while*) someone I was following posted about modern practitioners of the Germanic folk religion brought over by the Pennsylvania Dutch. I can’t remember if it was you or not, but do you know what I’m talking about anyway? I’m trying to find the modern group but I can’t remember the name they gave themselves or how they were referring to the religion itself, like what name they were calling it.

That's not quite an accurate description of it but you are probably talking about Urglaawe (which does have a relationship to PA Dutch culture going back to that period but in and of itself is a self-consciously very recent phenomenon), just based on the fact that I and others have talked about it before. If you were looking for a specific group it was probably Distelfink Sippschaft though they're not the only one.

It's possible you could also mean Braucherei, which is an initiatory folk magical practice with lineages that go back to that time period though that also has gradually but continuously changed.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're looking for a particularly obscure branch of religious folk healing, there's Braucherei (it's also known as powwow, but I'm not a fan of that term). It's pretty much magic, but make it pre-Reformation German translated to early American settler. You can cast spells using Scripture, and rituals need to be performed on specific holy days, etc. Hex signs might be involved, but probably not (could still work for a fantasy setting, though).

Since the PA Dutch who brought this over were mostly Protestants or Anabaptists, there really wasn't a central authority telling them not to do this (though I'm going to assume that the Church frowned upon it when they still had an influence). And there was at least one pretty infamous murder case where the victim was a Braucher.

I'd recommend these article for better details:

I understand why a lot of fantasy settings with Ambiguously Catholic organised religions go the old "the Church officially forbids magic while practising it in secret in order to monopolise its power" route, but it's almost a shame because the reality of the situation was much funnier.

Like, yes, a lot of Catholic clergy during the Middle Ages did practice magic in secret, but they weren't keeping it secret as some sort of sinister top-down conspiracy to deny magic to the Common People: they were mostly keeping it secret from their own superiors. It wasn't one of those "well, it's okay when we do it" deals: the Church very much did not want its local priests doing wizard shit. We have official records of local priests being disciplined for getting caught doing wizard shit. And the preponderance of evidence is that most of them would take their lumps, promise to stop doing wizard shit, then go right back to doing wizard shit.

It turns out that if you give a bunch of dudes education, literacy, and a lot of time on their hands, some non-zero percentage of them are going to decide to be wizards, no matter how hard you try to stop them from being wizards.

54K notes

·

View notes

Photo

was given this book by my dad bc he saw that i had a similar one on my wishlist + someone fucking stabbed it to death?? these holes go all the way through

#haxxy stop#stab wounds aside i'm really interested to read this#i've been craving information on pa dutch stuff / folk magic for months now#i can't believe i didn't ask my father if he had anything abt it. he has tons of this sort of book

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rukschtee or “Rest Stone”

So I have been reading through “The Red Church” and came across something that I just had to share. Before I proceed I will provide my typical disclaimer I am not an expert on the subject of PA Dutch Folk Magic and Healing, also don’t forget to consult a licensed medical professional, modern medicine is still important. So Any who....

The Rest Stone is a sympathetic Remedy used to absorb pain from wounds, and would be placed under the pillow of the party you wished to heal. After each use you would want to cleanse it. ex. bathe in salt water, and sunlight for a day (This is direct from “The Red Church”)

The Rest Stone would need to be a stone located at “an area of a boarder”, that is small, round and above ground. Traditionally this would be like a fence on the property and the stone would be close by the fence.

Once you find your stone the book also instructs you to speak to the stone. Again this is not a prayer, you will actually instruct the stone what you want from it. Repeated use of this stone is said to build a “memory” of what it is supposed to do. Some of this may not be specific to PA Dutch magics, still found this to be cool.

#sympathetic magic#folk magic#folk healing#padutchwitchery#pa dutch witchery#pennsylvania powwow#braucherei#sorry have to geek out

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello seeing all your posts on braucherei is so cool, im pure pa dutch and wanted to learn the folk magic,,, do you have any jumping off boards to start?

It’s an initiatory practice, as I’ve mentioned here several times, and as someone who is A. Not Christian and B. Was never fully inducted into the practice due to the death of my Lehrer, I should not be who you turn to to learn.

Your best bet is to look for an actual Braucher, build a relationship with the community you wish to serve and show yourself as one who is earnest and steadfast in your faith and your desire to serve in a way that is selfless.

Also the idea of being “full PA dutch” feels….. wrong to me bc PA Dutch is a culture within the American anabaptist faith. I don’t say that I’m “of PA Dutch descent” I say that my family are PA Dutch because it’s a religious and cultural group that can be joined by those who wish to convert to those denominations of anabaptist belief and who wish to live in those communities. I’m of German descent, not PA Dutch descent.

#you have to find a real Lehrer or Lehrerin#not a pagan on the internet who’s literally bastardizing the practice to suit a completely different religion

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buschgroßmutter, Shrub Grandmother, known throughout Pennsylvania Dutch and Germanic Magic.

This crystal pendulum talisman will undergo a strong ritual of consecration to the Buschgroßmutter, dedicating it to her and making it a powerful sacred object that establishes a connection to her. Buschgroßmutter is a powerful tree entity, akin to a forest Goddess, that is called upon for guidance, especially by Hexerei Practitioners. She was known throughout Germany, Austria, and later in America to some of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Known as Shrub Grandmother, she is appears as a wise older, mossy matriarch tree entity with long white hair and a magic staff. She is helpful to those who are kind and generous. She is often sympathetic of those who experience hardships in life, especially poverty, and offers support in trying situations. She is quite malevolent toward those who are malicious and problematic without reason. She is a stern, tough, no nonsense woman who is very knowledgeable. She is representative of strength, wisdom, independence, perseverance, and vengeance. She helps to provide wisdom and spiritual knowledge to you. She can be called upon for strong spiritual protection, combatting malicious people, magic, spirits, and entities. She would be considered darker arts to black arts and enjoys exacting revenge on people to obtain justice. She is quite ruthless and aggressive when it comes to vengeance magic. Please note, as stated, she is no nonsense! She WON'T tolerate any form of disrespect and may lash out at those who deliberately insult her. She doesn't cater to every whim; she gives guidance, wisdom, and assistance, but she expects effort on your part, as part of her lessons are about encouraging people to establish independence, personal power, and self-reliance. She enjoys nature, trees, plants and animals, they're all sacred to her and she protects them from spiritual attacks. This talisman acts as a strong energy conduit tuned to her power. This consecrated talisman is great for increasing personal power, gaining wisdom and insight, and increasing assertiveness. It is an excellent piece used to break free from spiritual constraints, develop independence, success, as well as hone your skills in vengeance magic. Additionally, it gives occult knowledge, usually via dreams or intuition.She often appears via dreams to inform you about important events, to give occult knowledge, teach you her magic, or to give messages. OFFERINGS: She appreciates thoughtful offerings, moss agate and tree agates are a favorite of hers. Pine needles, juniper berries, and thoughtful forest related gifts. Candles that are dressed with herbs such as mugwort. Honey bread or cakes. You may even plant a tree and dedicate it to her, or give her a figurine. She especially enjoys art and hand crafted items. Pendulum is great for divinatory purposes and receiving answers from her. It acts as a conduit to her for prayer requests. It can be utilized in ritual work for additional strength. Place near your pillow to receive dreams.

Talisman available at Temple Of Mars Hexerei on Etsy.

♦️WE ARE NOT AFFILIATED WITH ANY OTHER OCCULT SHOPS OR OCCULT PRACTITIONERS♦️

♦️Written descriptions and photos exclusively belong to us, Temple Of Mars Hexerei. You may not copy our item descriptions or photos for profit in any way, shape or form. We realize our item descriptions contain interesting, rare historical and metaphysical information, therefore you are welcome to share item descriptions for strictly informational purposes only, or strictly as a way to positively promote our shop, but when doing so, site that it comes from Temple Of Mars Hexerei. Thank you♦️

#witchcraft#pagan#magick#hexerei#hexeglaawe#heathen#folk magic#temple of mars hexerei#occult#pa dutch folk magic#Pennsylvania Dutch Magic#Germanic Magic#Spirit Companion

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Catch up work also means morning walks to reaffirm relationships with local spirits

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Bachelor’s Grove

Pairing: none

Summary: It’s Christmas 1885. Dutch is talking to anarchists, Hosea’s trying to scam an old man out of his house, and Arthur’s trying to figure out the very weird kid they just picked up. Nobody knows if they’re going to keep him, and John doesn’t want to go back.

Warnings: some gory imagery; almost-kind-of-you-decide-whether-it’s-magical-realism?

On AO3: https://archiveofourown.org/works/28368408

@wolfmeat, I was your secret santa! (I bet you never guessed. Love you)

i.

The sun glancing off the frosted windows of the station house blinds Arthur temporarily as he slips off Boadicea. He tugs off his heavy mittens to tie her to the hitching post, then stuffs his chapped hands quickly back into his coat pockets. There was an inch of ice on the water bucket this morning in camp. Arthur wishes Dutch had chosen a warmer morning to get caught with a known anarchist distributing anti-government literature.

He steps inside, and again can’t fucking see for a minute. The station’s dark even in daylight, old wood lit by dusty kerosene lamps that stink louder than the general musk of a constant cycle of drunks’ piss and tobacco spit. Arthur stops for a minute inside the door to let his eyes adjust, and the officer at the desk barks at him.

“What you want, son?”

“Payin’ a social call,” Arthur says, and takes the wad of bills Hosea counted out for him and tosses it onto the desk. The fella’s eyebrows hop nearly off his face, and Arthur scans the cells while he counts the money. It doesn’t take him long to pick him out. There’s not many people in the 18th district jailhouse wearing black silk and sitting on the cot like it’s a goddamn throne.

Dutch stands to meet him when Arthur approaches the cell, straightening his vest and checking the time on his pocket watch. As if Arthur were here picking him up from a social function, as if he didn’t have a huge purple bruise over one cheekbone.

“Good morning, Arthur,” he says, spreading his arms wide.

“Hosea’s gonna have your hide,” Arthur tells him. Dutch waves that away blithely, picking up his coat. He limps elegantly to the door of the cell and extends a broad hand to the jailkeeper, who doesn’t take it.

“A merry Christmas to you and your family,” Dutch says, beaming. Arthur can tell he’d like to knock the man’s teeth out. “Very sorry to insult your hospitality this way, but I’m afraid I ain’t inclined to spend another night in the company of the state.”

The guard isn’t impressed. “Go on,” he says, “before I change my mind.”

Dutch, Arthur notes with some dismay, is clearly in a good mood. For the first fifteen minutes of the ride back to camp, Dutch expounds on the uselessness of the state and the pathetic bankruptcy of soul that must lead a man like that wretch back at the jailhouse to feed his family off the profits of a government that’s nothing more than a tradition, and a cruel and foolish one at that, and Arthur picks at the loose wool on his mittens and watches his breath steam in the air.

“The true place for a just man, Arthur, is a prison,” Dutch shouts to him through the blistering chill as they wind south towards Bachelor’s Grove.

“True place for a man who can’t run on a sprained ankle, more like,” Arthur says, and Dutch throws his head back and laughs so loud a crow gets startled off the fence they’re passing by, and Arthur can’t help himself, he’s grinning.

“We’re onto something good here, Arthur,” Dutch says as they pass into the woods. “Silas tells me that Leslie Ashville—that haggard old maggot who owns the steel works where Silas’s poor cousin lost his hand last month—is losing his mind.”

“This the same Silas who got you arrested last night?” Arthur asks.

Dutch ignores him. “Old Ashville’s cracking, Arthur. Talking to folks as ain’t there and forgetting his own name. They say he ain’t gonna see the year of our Lord 1886, and it don’t seem right to me to let that fine gentleman die alone, with no one but his vampire of a nephew to carry on his legacy.”

“So,” Arthur says, starting to see where this is going, “you’re goin’ to apologize to Hosea for getting yourself arrested by inviting him to con a dyin’ man out of his money?”

“A dyin’ industrialist,” Dutch confirms brightly.

The camp’s a cluster of tents and wagons in a stand of oaks just south of the quarry pond, a respectful distance from the scattered headstones of Bachelor’s Grove cemetery. As they ride in, Arthur can see Hosea and Miss Grimshaw hurrying between the tents, ducking to look under the wagons and talking hotly. He catches Miss Grimshaw’s last sentence on the wind as he and Dutch ride closer: “...can’t have gone far in this cold.”

“What’s happening?” Dutch inquires as he slips down from the Count, favoring his hurt ankle just a little.

“The boy’s disappeared,” Hosea says, and Arthur doesn’t miss the relief that settles over Dutch’s features when he realizes this latest catastrophe is going to postpone a conversation with Hosea about his own sins.

“Go on, Arthur,” he says, “you look up thataways, and pray he ain’t fallen down that quarry. I’ll look off to the west, and Hosea, you and Miss Grimshaw stay here in case he comes back on his own.”

Arthur sets out grudgingly on foot. This ain’t the first time the kid’s given them trouble. In fact, Arthur reflects, he’s been more trouble than anything else since the moment Dutch caught sight of that rabble of homesteaders tying a noose to a walnut tree and decided to investigate. When they got closer and it turned out the fearful criminal due for a lynching that day was a twelve-year-old kid with an armful of onions and a crazy look in his eye, Arthur was the one who picked the kid up and carried him to safety while Dutch and Hosea argued with the would-be executioners. And then, Arthur was the one who got onion juice spit in his eye for his troubles and a nice set of bite marks on his neck.

The kid’s calmed down in the weeks since, or at least been effectively convinced Arthur isn’t trying to kidnap him, but he still bites. And apparently that ain’t all. Once they got him back to camp and a bowl of stew in front of him, he told Dutch his name’s John, his folks are dead, and he knows how to kill a man. Those facts, in that order, and if they didn’t light Dutch’s face up. Dutch likes the odd ones. Arthur tries not to think too deeply about how that reflects on him.

John’s odd, all right. He talks to himself all day; talks to animals too, and rocks and trees. And, strange enough, he’s a hell of a shot—hit every one of the cans Dutch lined up for him a week after he joined the camp, “just to see what he can do.” But he’s young, younger even than Arthur was when Dutch found him, and that’s a problem. Dutch said he’s safer here than on his own, Miss Grimshaw said a child his age got no business running with outlaws, Hosea said he ought to go to an orphanage, and John started hollering so loud nobody could finish the argument, and in the month since the question of what’s to be done with John has stood open. For now, it seems, he’s with them, but one of these days somebody’s gonna have to make a decision.

But maybe John’s made a decision of his own, now. This isn’t the first time he’s run off—he seems to have a special talent for that—but the longer Arthur trudges through the snow, the more it seems John might have made a real shot at it this time.

Arthur skirts the mouth of the quarry pond, looking reluctantly for any sign of a little body floating in the glassy dark water ringed all around with ice, and ascertains to his satisfaction and relief that John hasn’t drowned. He’d be sure to, if he had fallen, based on the almighty fuss he put up the first time Miss Grimshaw tried to get him to wash himself, shrieking that she was trying to drown him. Dutch finally intervened, grabbing John by his collar and belt and tossing him bodily into the creek, where it immediately became clear John’s never been in water deeper than his big toe. Arthur grins to himself as he picks around the clumps of buckthorn skirting the edge of the pond, remembering the look of dumb outrage on the kid’s spluttering face when he resurfaced and realized he was only knee-deep.

Arthur turns away from the quarry and up the snowy path towards the cemetery gates, squinting at the beaten stones that line the ground on either side. He can’t make out the names, but Hosea told him it’s mainly railway workers and homesteaders buried here, Russians and Germans and Irish. Folks who came from worlds away to get run over by wagons, or catch the grippe, or just to blow their own brains out when the crops failed and the government turned a blind eye. Ma’s buried in a place that looks like this. Pa too, maybe, only Arthur didn’t stay to see.

He watches a red-bellied woodpecker hammer busily at someone’s gravestone, and wonders if he should start to worry.

Then he turns onto the path leading up to the cemetery gate, a rickety wrought-iron arch planted between two spreading white cedars, and sees the kid. He’s sitting in the snow next to a tall granite monument, arms clasped around his legs and his head ducked down onto his knees, drowning in Hosea’s spare coat and Miss Grimshaw’s old scarf. His hair, as usual, hangs down over his pinched face like he’s trying to hide it.

“Hey,” Arthur calls out, and watches as John’s head snaps up like a spooked deer. But he stays where he is, body held tense and unmoving, as Arthur jogs forward through the icy cover of snow.

Up close, Arthur can see the kid’s been crying: his eyes are red, his cheeks are wet and chapped, and there’s a goddamn river of snot traveling down his chin. Still, when Arthur asks if he’s all right, he snaps, “A-course” and glares as if Arthur accused him of some grave offense.

“You scared folks, runnin’ off like that,” Arthur tells him, nudging John’s leg with the toe of his boot.

John shakes his head. “I ain’t scary.”

“Never said you was.” Arthur holds out a hand to pull the kid up. John doesn’t take it. “Come on now.”

John shakes his head, straggly hair flying side to side with the vehemence of his refusal. Stubborn as a horse’s ass is one thing they’ve already learned about John, and it ain’t Arthur’s favorite quality.

“What happened this time?” he sighs, settling himself against a gravestone opposite John. “Hosea said you just up and disappeared.”

John shrugs. “I ain’t talkin’ to you.” He’s picking at a loose thread on the sleeve of the coat, frowning furiously at it.

“What, did Grimshaw try to make you wash again? Because you know you stink.”

“Don’t neither.”

“You do,” Arthur assures him.

John sniffs, pulling his sleeve over his face and smearing snot even further across his cheek. “I ain’t goin’ back,” he says.

“Suit yourself,” Arthur says, shrugging broadly. “You wanna run off on your own, get yourself strung up by another pack of tetchy farmers, I guess that ain’t no business of mine.”

“No it ain’t,” John snaps, nodding in satisfaction.

“Awfully cold, though,” Arthur remarks, pulling his coat a little closer and squinting up at the sky. “I do believe that’s a storm comin’ in off to the east there.” John pokes his head up from the depths of Hosea’s coat to swivel his skinny neck around. “Still,” Arthur goes on, “you’ve obviously made up your mind, so I ain’t gonna try to talk you out of it.” He stands up, brushing snow off his coat. “Shame about them pies, though.”

John squints at him. “What pies?”

“Pies?” Arthur says. “Oh, the pies—oh, that ain’t nothin’. Only, I know Miss Grimshaw was plannin’ a heap of pie for Christmas. Mince pie, she said. Maybe apple. And Hosea, he’s made friends with a fella down at the slaughterhouse, figures he’ll get us a pig to roast.”

John stares. “I never seen a pig roast.”

“Well,” Arthur says, “I guess you ain’t gonna see one this year. Seein’ as you’re goin’ it alone now.” John squirms irritably in his snowy seat, frowning at Arthur. Arthur waits, listening to crows scream in the cedars.

“They was fixin’ to take me back to the nuns,” John says finally, in an unusually soft little voice. Not looking at Arthur.

“What,” Arthur says, startled, “Hosea and Grimshaw?”

John nods. “I heard ‘em. I was diggin’ in the dirt by that big ol’ stump an’ I was eatin’ some cheese an’ then I heard the lady say ‘this ain’t no place for a child, I heard him cough’ only I wasn’t coughin’, I just had some crumbs in my throat, an’ then Hosea said ‘he ain’t settlin’ in so good an’ I think we oughta see if them nuns’ll take him,’ an’ Dutch weren’t there and now he’s gone they’re gonna take me back there an’ so I got my coat an’ I snuck off ‘fore they could catch me an’ I ain’t goin’ back, if you take me back they’re just gonna make me go back to the nuns an’ they’ll cook me an’ eat me an’ then I ran an’ I ran an’ I heard someone comin’ so I hid behind the graves only then I thought maybe it was dead folks so I waited an’ then I heard someone else comin’ but it was you an’ I ain’t goin’ back, I ain’t gonna let ‘em do it.” He breaks off, breathing hard. His cheeks are red.

Arthur, a little dizzy trying to parse out that garbled spew of words, thinks he can see tears gathering in the corners of the kid’s eyes. Passing over, for the moment, the idea of cannibal nuns, he sighs and says, “Look, kid, ain’t nobody gonna send you anywhere without Dutch’s say-so, and Dutch ain’t decided yet.”

John frowns. “But he went to jail.”

“Yeah, dumbass, and I went and got him out,” Arthur says. “He’s out lookin’ for you right now.”

The kid’s eyes get wide at that. Arthur sees him take a shaky little breath and whisper something to himself that Arthur can’t catch.

“Come on,” he says, “I’m freezin’ my nuts off, and you ain’t gettin’ cooked alive by nobody this Christmas. Come on back, and I’ll tell Grimshaw an’ Hosea to lay off talkin’ about nuns.” He holds out his hand again.

This time, after a little consideration, John takes it, tugging hard as he struggles up to his feet. Arthur’s astonished at how light he is; the kid weighs nearly nothing. He sets himself on his feet, pulls Grimshaw’s scarf over his grimy face, and looks up to Arthur.

“An’ we’ll have pie?” he asks, hopefully.

“Sure,” Arthur nods. “Pie and pig.”

“I ain’t never had a Christmas dinner,” John tells him as they head back towards camp.

“What, never?”

John shrugs. He’s playing with the loose ends of his scarf, tossing them back and forth on his palms. “I heard about it, but I never had one. Me an’ pa, one time we stole a whole duck an’ he said that’s Christmas dinner, but it gave me the trots an’ I shit till I yelled.”

“Thank you for that,” Arthur says.

John nods, clambers over a wooden fence, and drops down the other side in a little flurry of snow. “What’s it like?” he asks, and the question’s so dumb and so oddly sweet that Arthur feels a little twinge in his chest.

“I dunno,” he says. “Like a party, I guess. Folks make good food and talk and sing, and go to church I suppose, only I ain’t been since I was a little, little kid, littler than you.”

“I ain’t little,” John interjects, scrambling over a rock.

“Well, I was,” Arthur says. “But my ma used to make supper, and we’d have turkey and fish and ham and potatoes and beans, and after she’d play on her organ.”

“What’s a organ,” John asks.

“A kinda musical instrument,” Arthur tells him. He hasn’t thought about this in years, can only vaguely picture the boxy little organ in the corner, Mama’s pale hands on the keys. The melody’s long gone. “Sorta like a piano, I figure, only it’s got pipes and pedals. My ma had one from a catalogue, and she said it kept her company out there in the country.” He remembers that: the way she’d sit at the organ in the evenings, not even playing some nights, just sitting. The way she cried when they came back from town and the organ was gone, sold to a man Pa found looking to pay good money for a secondhand Beckwith for his wife. Arthur remembers that, all right.

“So,” John says, “ya play music and ya eat?”

“More or less,” Arthur says. “S’posed to be some kinda holy day, but mostly folks just like to eat.”

They’re nearing camp, now, and Arthur can see the defensive curl in John’s shoulders. When he sees Dutch sitting at the camp table, though, he breaks away from Arthur’s side and dashes over, planting himself next to Dutch, arms crossed stubbornly over his chest.

“So you found him, Arthur,” Dutch greets him as Arthur approaches the table.

“Out hidin’ in the graveyard,” Arthur says. “I guess he prefers the company of dead folks to ours.” Dutch laughs, and John scowls.

“I weren’t hidin’,” he says. “And I didn’t see no dead folks.”

Arthur leaves him with Dutch, leaning intently over Evelyn Miller’s America and shooting Dutch shy reverential looks, and goes to find Hosea. He’s by the fire, poking at the dull coals, and he raises a hand as Arthur approaches.

“Found him all right?”

Arthur hums his yes, settling himself on the log Dutch dragged out of the woods as a seat. “Told ‘im we’d have pie for Christmas,” he tells Hosea. “He liked that.”

Hosea laughs. “Our little associate seems mightily driven by food,” he remarks drily.

“Like a damn pig,” Arthur agrees. Hosea chuckles, stretching his legs out and lighting a cigarette.

“I take it Dutch filled you in on his latest scheme,” he remarks, and Arthur can tell from the crinkle at the corner of his eye that excitement’s overtaken his annoyance at Dutch.

“The Ashville thing? He mentioned it,” Arthur says. “Somethin’ about stealin’ the fella’s legacy, or something.”

“Legacy, Arthur, is another word for a fat bank account,” Hosea says. “Besides, if we can play this thing right, there’s a roof over our heads in January. That boy’s already got a cough, and I for one would prefer not to spend the winter thawing out my backside every time I need to shit. I’ll need your help with the paperwork for this one, though.”

Arthur nods, rubbing his hands together in the growing warmth from the fire, and feels odd. Doesn’t know why he feels, suddenly, choked. He feels the way he did when Hosea and Dutch first picked him up, as though any wrong word would have him out on his ear or worse. Like all his words were caught in his throat, because he couldn’t pick the ones that were right.

Hosea, naturally, doesn’t miss a thing. “What’s on your mind?”

Arthur hesitates, chewing his lip, thinking about John’s blank, tearful face; about Mama crying the night the Beckwith disappeared; about old Leslie Ashville alone in his house on Cherry Street, talking to people who aren’t there. About the look on John’s face, hope and wonderment, when Arthur said Dutch was looking. For him.

“He’s scared of us,” he says finally. “Scared of you. And Grimshaw, but that’s—I mean, she scares everyone.”

Hosea snorts gently, but all he says is, “Give him time.”

“How much time?” Arthur says. “Dutch ain’t said if he’s staying with us.”

“Dutch’ll decide when the time’s right,” Hosea says, as if that settles it. As if Arthur hasn’t heard John whimpering in his sleep every damn night since they picked him up. Arthur turns to look at him and Dutch—two dark heads matched at the table—and hopes the right time’s soon.

ii.

The house on Cherry Street is three dusty stories of Italianate brick, lit from within by a dozen candles. From the street, it looks warm, even festive—someone’s hung a grand ring of pine and holly on the heavy oak door—but as soon as Hosea steps inside, he feels the chill. It’s different from the brisk winter evening outside: a dry, sickly cold that seeps through Hosea’s coat and settles along the joints of his bones.

Someone’s dying in this house. Hosea’s felt that cold before.

He follows the maid down the hallway to the parlor, past the cavernous recesses of unlit rooms. Behind the false front of lamps, this house is dark and silent, save the single corridor of light that traces a line down its center. Hosea watches a chandelier of thick, ugly crystals sway mutely above his head as he passes beneath, and fixes his mind on his story.

It’s his second visit to the Ashville mansion. On the first, he introduced himself as William Ashville, the long-lost offspring of the affair a group of Ashville Steel workers told Hosea about over bad whiskey at the Red Hen. It seems the story’s well known among Ashville’s discontented employees: the lady’s name was Eleanor, and Ashville promised her marriage, then left her at the altar and came west instead to make his fortune off the work of honest men. Nobody’s been able to give Hosea an exact date, but one fellow, with a rough white beard and teeth so sparse and loose Hosea suspects he lost one in his beer over the course of the conversation, remembered the year Ashville turned up in Chicago as 1856, so Hosea’s dated the affair to about thirty years ago. He considered, briefly, having Dutch step in as the prodigal bastard, but this part requires a delicacy that Dutch, for all his charms, lacks. Besides, Hosea flatters himself that he can still play thirty. He borrowed a bit of Dutch’s pomade for the occasion, and a little of Susan’s face powder—and besides, old Ashville’s eyesight isn’t that good.

All in all, Ashville took the news of his unwitting fatherhood surprisingly well. Hosea, who after thirty-odd years of disregard for the fairer sex unexpectedly became surrogate parent to an unwashed teenage criminal, can attest to the shock that comes with that sort of arrival. True, there was a moment of initial skepticism from Ashville, but the family bible Hosea produced (purchased from a bookseller in the Levee, embellished by Arthur with the names of a whole fictitious lineage for poor forgotten William Ashville) seemed to turn the tide of his disbelief, and the love letter Hosea wrote after making a study of Ashville’s handwriting clinched the story. Today, Hosea’s back, in character as young William, with two missions: to lend cheer to his aging father’s lonely indisposition, and to lift a copy of the old man’s will.

He hears Ashville’s voice before they reach the parlor: halting, guttural, like water through a clogged pipe. He’s murmuring about the newspaper, about catching a train. The maid leads Hosea into the room, where an unfed fire lights a frail circle around Ashville’s chair and casts long shadows across the rich Turkish carpet, and Hosea can see that it’s empty; that Ashville’s talking to no one.

“Sir?” the maid says, leaning down to the high upholstered chair by the hearth. “Young Mr. William here to see you.”

Mr. Leslie Ashville, sole owner and proprietor of the Ashville Steel Works, looks molded of lean clay. He’s wrapped in a brocade robe that looks like it hasn’t been washed since the early ‘70s, his head bare save the airy thatch of white hair shrouding the glare of his scalp. Hosea finds him fascinatingly grotesque.

“Good evening, father,” he says, settling in the chair across from Ashville, who acknowledges his presence with a faint hum that turns into a cough.

“Is that you, William?” he croaks, finally, and Hosea leans closer to take his hand.

“I’m here.”

“Thought I saw your mother last night,” Ashville rasps. “Thought I heard her, in the walls.”

“Perhaps it was her spirit,” Hosea offers. “I do believe she’s glad to see us reunited.” There’s a bulk of shadow off behind Ashville’s right shoulder in the general shape of a writing desk. Hosea makes a note, and refocuses his attention on Ashville.

“She was beautiful, your mother,” the old man says, and then he’s off chasing the thread of that long-forgotten memory, a thread that seems to unravel every time he reaches another knot. Hosea plays the dream-weaver, dropping a hint or a suggestion every time he hears the man’s voice falter. It’s fragments he offers the old man, things that could have belonged in any lifetime, things easily forgotten and more easily misremembered: the color of a dress, the fate of an old school friend, the name of a parson or a shopkeeper; always just enough to get Ashville’s feet back under him and send him off along another strand of reminiscence. Together, between Ashville’s dying memory and Hosea’s healthy imagination, the two of them write Leslie and Eleanor’s love story by the light of the fading fire as the evening deepens into night.

The bells of St. Clement’s are chiming ten when it finally happens: Ashville stammers, trails off, and doesn’t look to Hosea for the next line of his memory-fantasy. Instead, his ancient head droops and lolls magnificently, and after a moment’s pause Hosea hears a loud, guttering snore. Ashville’s asleep.

Finally.

Easing himself off the slick horsehair of his seat, Hosea crosses to the shadowy desk he noticed earlier in the evening. It’s a heavy thing, made of rich cherrywood and full of drawers and cracks and pigeonholes. Hosea returns to the center of the parlor for a candle, and sets to work searching the desk, an ear out for the maid’s footstep or a shift in Ashville’s steady, ugly breath.

An hour later, he’s slipping out the front door into the midnight chill, bidding the maid a happy Christmas, with the thin pages of Leslie Ashville’s will flat against his side under his heavy coat. He found the lockbox easily enough, stowed in a deep drawer under a sheaf of old bills and past due correspondence, and five minutes was all it took to break the lock while Ashville snored in his seat ten paces away. The will itself is simple: all Ashville’s wealth and property deeded to his nephew Fred Ashville, the current junior proprietor of Ashville Steel and the devil himself as far as most of the working population of the west side’s concerned. Hosea thinks, as he makes his way down Cherry Street under a soft flurry of snow, that they’ll be doing mankind two services this December: keeping Leslie Ashville company on his trip towards the undiscovered country, and seeing to it that Fred Ashville never prospers again.

The campfire’s burning unusually bright when Hosea makes his way through the last bent hickories of Bachelor’s Grove. At first, Hosea thinks it must be Dutch who’s up, caught in one of those odd brain fevers where he can’t sleep till he’s filled fifty pages with words about God and death and man’s perverse indifference to nature—but when he gets closer he sees that it isn’t Dutch at all. It’s John, hunched gracelessly on one of the logs like a disgruntled little bullfrog, tossing little twigs and dead leaves into the flames to watch them sizzle and smoke. His lips are moving, but from his distance Hosea can’t tell what he’s saying. It occurs to Hosea that he’s spent quite a lot of his time lately in the company of people who talk to the air around them.

That’s the thing that worries Hosea. It’s not the taking him in—they’ve done as much before, and not only with Arthur. Hosea knows what it’s like to be ten and cold and empty as a tomb on Judgment Day, and he’s not about to turn away hungry mouths when there’s room at the fire and enough in the pot to go round. Besides, he’s never regretted letting Arthur stay. But Arthur was fourteen, not twelve, and Arthur didn’t talk to people who aren’t there. Arthur was just a kid whose father hit him too much, and a damn good thief. John’s something else, and after weeks Hosea still isn’t sure exactly what.

Hosea approaches the fire, and John starts, shoving his hands under his armpits as though Hosea just caught him doing something bad.

“It’s late,” Hosea observes.

John shrugs. “I’m not tired.” His eyes are huge in the firelight, and Hosea has the feeling he often gets when John looks at him—that the kid is sizing him up, calculating where to strike if trouble starts.

“I can see that,” Hosea says.

“Is he dead?” John asks. Arthur’s been telling him about the scheme, then. Hosea makes no pretense of sensitivity when it comes to death, but having spent a full evening playing the loving son to Ashville, Sr., he feels a mite put off by the ghoulishness of the question.

“Old Ashville? Not yet,” he says. “Go to bed.”

John doesn’t go to bed. He leans back, firelight catching the ragged ends of his hair, and says, “I seen a fella die once.”

“So have I,” Hosea tells him.

“He was coughin’,” John goes on, undeterred. “Blood was comin’ out of his mouth, an’ out of his nose, an’ all down his shirt an’ then—” he pauses dramatically, gathering a handful of rotting leaves into his grubby hand, “—then he shit in his pants, an’ a whole lot of blood came out his mouth, an’ the lady said he’s really dead now.” He tosses the bundle of leaves into the fire, which sends up a small gasp of muddy smoke. Hosea wonders who the lady was. Wonders where this child’s been, to tell that kind of story.

He doesn’t ask. “You’ve been dreaming,” he says, and it’s less a guess than most of what he spun for Ashville earlier tonight. He’s seen that spooked look before—seen it in Arthur’s eyes when he was barely older than John and still fighting his father off in his sleep; seen it in his cousin’s eyes when he came back from Sharpsburg a leg light and ten times heavier for it; seen it in Dutch, sometimes, too. Hosea knows too well what nightmares look like.

John scrubs at the snot trailing from his nose and shrugs. “I seen it,” is all he says. But he shudders, and his skinny shoulders hunch smaller against the night.

He’s clearly not going to go back to bed, and in a way, Hosea can’t see why he should have to. It’s well past midnight now, but Hosea isn’t tired either. The moon’s high, the air’s quiet, and he’s got a job to do. He might as well have some company while he does it.

“Come on,” he says, waving towards the table. John follows him over, and Hosea draws Leslie Ashville’s will from under his coat and spreads the pages across the pocked wood. John, who can’t read and tried to bite Dutch when he offered a lesson, peers at the frail sheets with the curiosity of a spider inspecting a particularly fearsome fly.

“Now,” Hosea begins, “what we’ve got to do is this.”

iii.

On Christmas Eve, something happens.

John isn’t sure at first what’s happened, only that folks are talking real loud and nobody’s telling him anything, but that’s not new. He goes into the trees and finds a big old stick and hits a stump till it falls into soft, stinking rubble, and stamps in the snow till there’s a flat circle all around. There’s a fat squirrel running around the base of a tree a ways off, and it stops for a minute and sniffs in John’s direction.

“I ain’t smelly,” he tells the squirrel. “An’ I ain’t stupid.”

The squirrel twitches and scoots away, tiny claws on the snow.

“John!” Arthur calls, and John kicks bits of rotten wood across the ground until Arthur comes through the trees. “Get your coat on,” he says, nodding back towards camp; “we’re goin’ into town.”

“Why,” John asks. He thinks about a wagon full of kids, rolling through the iron gates of the orphanage. He thinks he could kill Arthur, if he tried to put him in there. Kick his nuts, put his thumbs in his eyes and squeeze the jelly out, like that fella did to Pa in the bar, get his gun off him and point it to his heart.

If he had to do it, he thinks he could. He’d be sad about it after, though. He likes Arthur.

“Ashville’s dead,” Arthur’s saying. His face is split with a grin; John’s never seen him smile much. “We’re gonna be rich. We’re gettin’ the house.”

“Oh,” John says. He can see the old man in his head, wrinkled and tiny in a house like a tomb, the way Hosea told him the night he came back with that secret pack of papers. Worms in his nose. Gobs of blood pouring, pouring out of his slack, black mouth. “Really?”

“Really.”

It’s a cold ride into town, perched on the back of Arthur’s horse with his arms tight around Arthur’s middle. John can hear Dutch talking up ahead, but the wind’s too quick to hear the words. John probably wouldn’t understand it anyway. He can’t understand half what Dutch says. He’s never met anyone as smart as that. He wonders when Dutch is going to find out that John’s dumb as a rock. Dumb as a rock and the devil in him, that’s what people say. Dutch don’t seem to mind the devil so much, though. John doesn’t know what to think about that.

How exactly they got this house, John still doesn’t understand. Hosea took that dead man’s sheaf of papers, and said we’ll write these out again, and he and Arthur sat at the table for hours inking and scratching till Hosea said it was all perfect, and then there was some meetings with lawyers and magistrates and aldermen, and then it was all done, only the old man weren’t dead. John asked if Dutch was going to kill him, but Dutch just laughed and said I ain’t a murderer, I’m a philanthropist, and Hosea said that’s my old dad you’re talking about, and now John isn’t sure. But Arthur said it’s like a game, don’t you worry, and when the old man dies we’ll take his house, and now he’s dead. John squeezes a little tighter around Arthur’s middle, and tugs himself closer in the saddle.

They’re riding through the grand part of town now, the part where every house has three floors and curly carvings on the windowsills and a pretty little tree out front all its own. John remembers sleeping here one night last summer, after Pa died, in a little stand of apple trees behind one of the mansions. He ate the hard little apples off the ground till his stomach hurt, and fell asleep in a shed, and in the morning an old African man came along and told him to run or he’d be in a pile of trouble, so John ran. He’s scanning the houses as they pass, trying to remember which one it was with the apples and the old man who said to run.

The house where Ashville died is cold, and it smells like dust. John watches Arthur and Dutch and Hosea and Miss Grimshaw striding through the halls, crowing and laughing and saying Shakespeare, and looks to see if he can spot the place where the old man died. But there’s no blood on the floors or the furniture, just warm leather and shiny velvet and wood that gleams like gold when Dutch pulls back the heavy curtains and lets the winter sun spill over the room.

“Merry Christmas,” Dutch booms, and Hosea says “hear, hear,” and John wonders if the ghosts can hear them too.

Arthur takes him upstairs. Upstairs is a row of rooms, each the size of a house, each full of cobwebs and dead beetles and beds with heavy ceilings. Arthur tugs the curtains aside in each room while John sneezes in the bright dust and pokes at the silky wallpaper.

Then Miss Grimshaw comes up the winding staircase and sets them to work, hauling carpetbags up the stairs and beating dust out of the duvets with an old broom from the kitchen. She snaps orders like a policeman and drags John by her iron knuckles to a room at the end of the musty hall and tells him it’s his. John suspects a trap, but Arthur laughs and says I ain’t bunkin’ with you no more, and John understands. After supper that night, when Dutch and Hosea pop open a bottle of wine they found in the cellar and Arthur starts singing and Hosea says John can’t have any wine and Dutch says it’s all right and Grimshaw says it ain’t, John sneaks upstairs to the Room That’s His, and wonders when they’ll drop him at the orphanage.

He’s lying in the dust, watching moonlight crawl over the tall windows, when he hears the voice. It doesn’t sound like Dutch or Hosea or Arthur, but it’s a man, and it’s saying his name.

John.

John.

John stands up. The door to the hallway opens, opens without him touching it, and on the other side’s a man who looks familiar. He’s not tall and he’s not short, with a little mustache and a fancy suit, and his hat reaches towards the ceiling and his eyes are fixed on John’s heart and not his face.

“John,” he says, “I’ve missed you.”

Then his face swells and melts. His eyes are hot black hollows, crawling with white worms, blood pouring out his mouth. John watches the river of black gore, swimming down his front, running over the rich, dusty carpet, the smell of shit rising thick and hot around him, and the man twitches and moans and heaves. Blood pouring out his mouth. John tries to scream and he can’t scream, he can’t breathe, and the smell of blood and shit makes him gag and retch, and the blood keeps coming, a black waterfall streaming from the strange man’s face as he sways and leers and shimmers in the dark.

“John!”

Someone’s holding his shoulders, shaking him. There’s carpet under his feet, warm and soft, and he gags, and hears Arthur say shit.

He opens his eyes. He’s in the dark, in the hallway, and Arthur’s here in a big white shirt with his hair mussed up from sleep. He’s got John by the shoulders, and he’s got an odd look on his face, like something bad is happening, and John wonders if it’s happening to him.

He looks worried, John realizes with a muffled shock.

“You okay?” he’s asking, and John shakes his head before he can think about it. His heart’s beating like an army drum. He thinks he can feel it shaking his whole body. He steps from foot to foot on the swampy carpet, and realizes his pants are wet. “What happened,” Arthur asks.

John’s stomach jerks and twists inside of him. If he tells Arthur the truth, he’ll be gone by morning.

Arthur’s hand’s at the back of his head, in his hair, steady and warm.

“Come on, kid.”

John sucks in air.

“It was him,” he whispers. “It was the devil.”

Blood pouring out his mouth.

Arthur sighs, a little sound that’s almost a laugh, and says, “There ain’t no devil here. You had a dream.” He leans in, smelling like wine and horse, and pats John on the back, one arm around him pressing close, his scratchy chin brushing against John’s forehead. John thinks it’s a hug. He doesn’t know what that means.

“I ain’t good,” John starts to tell him—heart in his stomach, stomach in his throat. “I’m crazy an’ I’m bad an’ I got the devil in me an’ he follows me an’ last year he made me shoot a man till his brains came out through his nose an’ the nuns’ll give me back to him,” but Arthur stops him, hand on his cheek, shaking his head and saying no, no, forget all that, you’re dreamin’, there ain’t no devil and there ain’t no nuns here. You’re home now, John. Forget that.

In the end, Arthur picks John up like he’s a kid, and John’s too tired to complain. He wraps his arms around Arthur’s neck and lets him carry him down the hall, away from the room with the devil’s blood soaking into the floor and into Arthur’s room, where there’s a heap of orange coals in the hearth and a wooly blanket that Arthur wraps him in once his sodden pants are gone. They sit by the fire, John a mute cocoon and Arthur more than half asleep, and Arthur pulls out his notebook and shows John a funny drawing of a man with an apple for a head.

John thinks about home.

“You’re a good kid,” Arthur says, his voice soft and silly. He’s drunk. “Dutch ain’t gonna send you back, y’know.”

John’s throat aches like there’s someone punching it. His cheeks are hot, lit up by the fire and the tears spilling up and over his eyelids. He can’t answer back. He thinks about a flat plain, gray grass wrinkled by the wind, and a heap of rocks at the edge of a hill. He can’t get the picture out of his head. Can’t get the devil’s voice out of his throat.

“You’re home,” Arthur says, and the warmth of the fire swallows him up, and he sobs into Arthur’s side for a long time.

Down the hallway, in the darkness, the door swings silently open and shut.

#rdr secret santa 2020#rdr2#john marston#arthur morgan#rdr2 fic#we got some christmas here and we got some wild handwaving towards the background plot i had in mind but didnt have the energy to write#this really might not make sense but it is gifted with love to my perfect wife

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

If others ask this, i apologise for asking again, but what does Urglaawe do that other US pagan groups do not?

Never any need to apologize, but to the first anon, you were, in fact, the first.

Just as a disclaimer, I think everyone knows this but I am not an Urglaawer myself, but I have a lot of friends who are and have participated with them as a friend and guest.

Uglaawe, for those who haven’t heard of it, is a type of heathenry that draws primarily on the folk traditions of the Pennsylvania Dutch (i.e. PA German, or Deitsch). It first started to be articulated around 2007-8 by Rob Schreiwer (ex-steer of the Troth) and some others. In incorporates a lot of traditions that developed in the last few hundred years, such as folk and fairy tales; its own calendar/holidays; recognition and veneration certain distinct historical, ancestral, and/or spiritual beings; and traditional magical practices.

It takes a lot of flak in heathen communities, online or in-person, for being historically inaccurate, but historical accuracy has never been one of their stated goals so much as doing whatever works for them. That doesn’t mean they just do whatever they want arbitrarily, but it means their development is guided by a different set of principles than what guides most other heathens. An example of a criticism they get is that they worship deities that have been rejected as ahistorical by most heathens, such as Zisa, but it isn’t so much that they think she is historical as it is that they don’t really care, or at least that isn’t the basis of them recognizing her. This should have earned them a big “I told you so” when heathens discovered Philip Shaw’s book about Easter, since Urglaawer had been worshiping Easter through the whole period of heathens saying she was fake, but nobody really seemed to notice that. Some Urglaawe traditions like their variants on runic lore were probably either made up in the last few centuries or at least heavily impacted by intentional invention during that time, because they’re just a little too much of what one would expect based on what was believed about Germanic culture in like Grimm’s era, but they know all of that and work that recent history into it (which is like many Scandinavian heathens who have no problem celebrating traditions that they know where invented in the 20th century).

So when I was accusing recons of trying to “escape from history,” that’s an example of something that Urglaawer definitely do NOT do, they see themselves as active participants in a complex web of history that includes everyone, not just a narrowly geographically- and temporally-bound focus. While recons struggle to find the philosophical tools to give life to their dead religion (note: I like Marc personally but the sliver of overlap in the Venn diagram of our heathenries is barely visible under a microscope), Urglaawe was living, even if only as a seedling, from the moment it was conceived of. In my opinion this makes them more historically accurate than recons on like a meta level. They don’t hold up to, like, reenactor standards the way a recon might, but their concerns, motivations, and methodologies are more like actual historical pagan peoples even if the expressions of it are novel.

When it was getting started it borrowed heavily from Ásatrú, meaning early 2000′s American Ásatrú, taking that to be a good faith representation of Germanic traditions, and some of that is still part of it. But part of Urglaawe’s development is the actual hard work of language-learning, folklore collection, translation, and teaching so as time goes on it continues to individuate more from other branches of heathenry, which is a good thing.

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

While driving home from PA yesterday, I took a detour to Bethlehem to meet up with a friend... and ended up taking a wrong turn and getting a little lost west of 476. Before I realized it and righted myself, I passed the barn at the top (and later the garage at the bottom), and excitedly pulled over to take a pic of the hex signs.

So-called hex signs are a very old Pennsylvania Dutch folk-art tradition, usually found as barn decoration. While they are sometimes prepared as separate pieces and mounted, the “serious” ones are painted directly onto barns like this. (The white arches over the window are also a common local feature of barn decoration.)

There is some controversy over the common English name, “hex sign”, because they don’t actually have anything to do with witchcraft or putting hexes on people... except, I would note, in the very broadest of senses (see below). The popular term comes from what might be a misunderstanding by a scholar who did some early chronicling and interviewing about them. Most of the designs are luck-related in one way or another. (Supposedly for general luck, happiness, good rain, fertility, welcome, etc.) As I said above, that sort of propition of good fortune could, if you squinted, sort of be related to invocations in witchcraft (”hex” is related to the German word for witch, “hexe”; and while most people think “hex” means “curse”, it could mean any kind of magic, helpful or harmful). BUT, the actual makers and users of the folk-art in Pennsylvania undoubtedly do not regard it as “witchcraft” per se. At most, they may regard them as “folk magic” that they relate to a Christian tradition. (There are some designs with Christian origins or allusions.) There is one source in Wikipedia that I’d like to follow up with, that suggests the designs may have pre-Christian Alpine origins, which is pretty interesting.

Anyway, it’s silly that I grew up in the Philadelpha area and of course knew about the Pennsylvania Dutch, and hex signs, but we never took the short trip up to drive around the area with the highest concentration of decorated barns. (They became quite the tourist draw in the early 20th century.) I’d still like to do that at some point.

The barn and garage above would have to be on the eastern fringe of that area, and while I’ll try to see if there’s any info on the barn online somewhere, at the moment I don’t know its provenance. (They may be modern rather than historic.) Nice job on the barn, though!

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

A/N: ok hi I wrote this listening to my Arthur playlist so like. It gets emotional. I decided to give my idea of what the whole, Arthur returning to Isaac and Eliza to find two crosses in their place thing. Details to keep in mind: I imagine Arthur to have been around 21 when he and Eliza had Isaac, which would make him 25 in this. I also included a tiny tiny part of an oc called Annie, but she’s literally just a memory so she’s really not that significant. Just a heads up for any confusion! Enjoy!

It was muscle memory at this point. The ride to the house just in the corner of the woods. The trail between trimmed shrubs and branches that created an arch above it, almost like it was welcoming him into its grasp. It was a pretty house, too, no doubt. Folk wondered how Eliza Holliday, the sweet, quiet barmaid could afford something like it. She had been living with her parents in their tiny little shack in town, when all of a sudden word spread that the house in question was bought by her. It was strange enough that she could afford it, a girl her age, and even stranger that she’d occupy it alone. Folk couldn’t make sense of it.

No one linked it to the heist. The answer to their question was right in front of them, clear as day, but no one could think sweet little Eliza could be responsible for the robbery at the mayor’s house, during a party at that. It didn’t even enter their mind.

It wasn’t her. Arthur, however, the same can’t be said for. No amount of persuasion could have made Dutch and Hosea part with such funds, so he reckoned he’d get it himself. With the help of Annie, Eliza’s strange friend, the possibilities were endless. She was a brave girl, Annie. Did more for Eliza than Arthur even knew. Made her smile when she felt down. Planned the Mayor Heist. Died for her. Arthur was forever indebted to Annie. A brave, strong girl. Braver than he could ever be, he imagined. To think, she ran with a gang he was supposed to hate. Their leader was out for Dutch’s blood. Annie may be gone, but the leader she turned on wasn’t. She won that fight.

Her name was Willy, which is odd. She wasn’t a fan of Wilhelmina, according to Annie. She was a good leader at some point. Raised Annie from when she was a little girl. Willy found her wandering around, Annie only 8 years old, looking for Dutch. They both had the same mission even then, only with very different reasons. Willy wanted Dutch dead. Annie was looking for her uncle, at the wishes of her dead mother. Willy worked her magic and did so for 10 more years, turning Annie away from her old idea of Dutch. Her mother’s idea of him. Manipulating her into thinking she was the best parent for her. Annie’s story was a wild one, but she had a kind heart. Right to the end.

Arthur still thought about her. It was impossible not to. Eliza loved her, he knew that much. And Annie loved her right back. The last thing she said to him before she faced Willy one last time was to keep Eliza and the baby safe. He hadn’t even been born yet, and Annie was already looking out for him.

Eliza wasn’t the same after Arthur returned to the house with Annie on the back of it, wrapped up in cloth from head to toe. He understood full well how she felt about her. It was fair, too. He knew he wasn’t in love with Eliza. And she wasn’t in love with him. Both had different people on their mind, and both needed each other to hide that pain.

He didn’t want to think about Mary. Eliza and Arthur weren’t romantic anymore, if they ever really were. They were close, though, and she always encouraged him to talk. She was good at that. And it sure was refreshing to have someone listen. Dutch and Hosea meant the world to him, as did Bessie and Annabelle, but he never felt he could mention Mary around them. He didn’t want them to think he was a fool. He already thought it about himself.

He always got lost in thought on this ride. It was a nice area, full of birds singing and wind rustling the trees. He was glad Isaac was going to grow up somewhere as nice as this. His own childhood wasn’t something he wanted to throw on his own son. It was one of the reasons he didn’t want him constantly moving with the gang, and why he and Annie bought the house for Eliza. He deserved a settled childhood, away from the life of an outlaw. A normal life. If Arthur couldn’t have it himself, he’d make sure his son could.

He didn’t like being away from them. He promised to visit for Isaac’s fourth birthday, which would mean 2 visits that month. That promise couldn’t be kept, which broke Arthur up inside. Trelawny messed up information he had on a job, and it led to the gang hiding out in a barn for a week. So now, a week late, Arthur was surprising them.

His favourite part was hearing the cheer Isaac let out when Eliza would call for him. He was growing so fast, it was like he defied the laws of time. He was a curious kid, too, always running around the garden and getting intrigued by the smallest things. Eliza told him the boy had stared at a blade of grass for 20 minutes, totally amazed. She reckoned he’d be a drawer some day, just like his Pa. it was probably the only trait Arthur wanted to pass down.

He was nearing it now, just about to turn the corner towards the final trail to the house. He imagined the smile on Isaac’s face as he hopped off the horse and ran to hug him. His little boy. God. He never thought he’d get to say that. And Eliza. He was lucky to have her in his life. So damn lucky. There was a love there, even if it wasn’t romantic. They cared for each other very much. Their little family of three.

The horse slowed as the house came into sight, and Arthur prepared his big announcement of his presence. Unconsciously, a smile was forming on his face. He missed them more than he knew. He was finally here. The beautiful house that meant so much to him. The trees that surrounded it making it look like something out of a fairytale. The crisp white paint that was still as bright as the day he painted it. The porch he sat at with his little family and watched the stars on.

A wooden cross. A second cross, right beside it.

The smile dissolved, and was replaced with confusion. He urged the horse to stop, pulling the rains and hopping off. A name was carved into each cross.

In an instant, he was back on the horse, riding back through the trail, that once seemed like something out of a dream. Now it was a nightmare, as branches reached for him and leaves begged him to stay. The wind howled instead of lightly whistling, and the shrubs seemed to close in on each other. He had to go. He had to find them.

The town wasn’t far from the house. Passers-by jumped as he dashed through it, towards the saloon where it all began. She would be in there, standing at the bar like she was that night, a smile on her face. Isaac would be there too this time, running around the saloon or playing on the counter. There would be an explanation. They’d be ok.

The music came to an abrupt halt as he burst into the room, throwing the wooden flaps open and stopping where he stood. Mickey stood at the bar, drying a glass. The second he saw Arthur, his face paled. The boy was red in the face and tears were already streaming down his face. His breath was hitching as he stood there, waiting for the saloon-owner to tell

him.

‘Arthur...’ he began.

‘Where are they?’ he said, his words shaking as they left his mouth.

Mickey stared at him, unable to form the next sentence. He was an older man, late fifties. Not only an employer but a friend to Eliza. He was kind to Arthur, too. Didn’t even complain when his presence prompted a shootout in the bar. Mickey was a good man, and knew what he said next would break the boy’s heart.

‘I went to the house and... and...’ began Arthur.

‘I’m sorry,’ was all he could respond.

‘Where are they, Mickey?’

‘I’m so sorry, Arthur.’

Arthur stood for another moment, breathing heavily, unable to control it. The moment he raised the gun, Mickey threw his hands up. As frightened as he was, he knew the boy was just processing. To hear your world has been taken away isn’t easy.

‘Stop lying to me!’ said Arthur, though it sounded like a whimper now. He wanted so desperately for it to be a lie.

‘Son,’ came a voice behind him. ‘Lower the gun.’

Hosea. Arthur turned to see him, standing with a newspaper in his hand and a look full of sorrow on his face.

‘News got to camp after you left,’ he said. Arthur stared at him, the gun already fallen to his side. The tears had stopped. Now it was just shock. Hosea held the newspaper towards him. He read the words, which barely sunk in, and could only stare. ‘Young mother and child shot dead in Home Robbery’. The saloon matched his silence. His feet slowly moved out the door, stopping when the air from outside hit him. Hosea followed closely behind him. The boy practically fell into his arms, hiding his face in Hosea’s shoulder.

He hadn’t cried like that since he was a child. Hosea only remembered one time, when Arthur was around 15, that he sobbed talking about his mother. It was the first time he really opened up to Hosea. He was a broken person when they first found him. They healed that somewhat, then Mary came along and broke his heart. And he was right back to the broken child they’d found years before. Eliza and Isaac healed that again, only for that to be torn away from him too. Hosea wished it could be different. He wished the life they lived could be better. He wished Arthur could be happy and keep the things that made him that way.

But it just wasn’t like that. And it never would be.

#rdr2#red dead redemption 2#arthur morgan#dutch van der linde#john marston#young arthur morgan#isaac morgan#eliza#hosea matthews#fic#my writing#long post

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

All About Barn Stars & “Hex Signs”

I’ve written and re-written this post at least three times now because there’s so much to cover and it’s something I’m passionate about. Hell, there are multiple people who have devoted their lives to this topic! So what follows below the cut is the most bare bones, straight-to-the-point version I’ve managed to do. I can expand on it later if there’s interest or I can point people to some good sources for their own research.

Note: Image heavy post with most of the photos courtesy of the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University.

So first: The Name

The tradition of painting these images onto barns goes back more than 200 years in Pennsylvania alone. Celestial images can be seen on multiple household objects in PA Dutch culture and back in Europe where the immigrants who settled here came from.

In the Pennsylvaanisch Deitsch (PA Dutch dialect) there are two terms most commonly used to describe these images. Blumme (flowers) and Schtanne (stars). While not reserved exclusively to refer to the art, these words predate anything else that we’ve called the images.

[Image description: 24 photos of barn stars next to each other to show off the similarities and differences. Good examples of Blumme style can be seen in the bottom three photos of the first column. The entire top row are great examples of the Schtanne style.]

Hex Sign is the most common name today thanks to a man named Wallace Nutting who created Pennsylvania Beautiful, a collections of images and descriptions of rural Pennsylvania created for a burgeoning tourist industry. According to a single source, the images were supposedly called “Hexafoos” or “Witch’s Foot” and were part of an ancient traction of warding off the devil. It should be noted that the word Hex means witch in the dialect.

[Image description: an ink image of a barn from Earl Township, Berks County featured in Wallace Nutting’s Pennsylvania Beautiful (1924) which links to the naming mix up.]

While Nutting likely did not mean to confuse people, it is VERY likely that there was some miscommunication. A “Hexefuss” (the standard spelling) is a mark left behind by a witch, often resembling the footprint of a bird. Depending on the type of animal print the mark can have slightly different names but crows were most popular in legends so that’s what’s linked to Hexefuss the most.

Another sign that Nutting was confused is the fact that the other domestic objects in his work were decorated in a similar manner but were not also given the title and mythical meaning.

Next: The Meaning

So if they weren’t to ward off evil, why were they there? What did they MEAN?

No one really knows. Some think it was “just for nice” since they’re often only on the side of the barn that’s facing the road. Celestial symbolism has deep ties with folk culture and the Blumme and Schtanne images could have different associations with biblical and natural events.

While most barn stars do not have any major superstitious or magical meanings, we will likely never know for sure. Barn blessing were not uncommon, they just often took a different form such as a paper charm hidden under floorboards or in peg-holes within the frame.

If you’ve heard that all stars have “meaning” like fertility, love, etc. you are likely thinking of the transformation to the art form that came around the 1950s.

The 1950s was a time of increased interest in Dutch Country. Many were fascinated with the “sectarians” or “plain people” like the Amish and even though they did not decorate their barns, business minded people knew there was money to be made. The “church people” or “gay” Dutch were the ones who decorated and who are responsible for the signs which before this point had not been sold commercially.

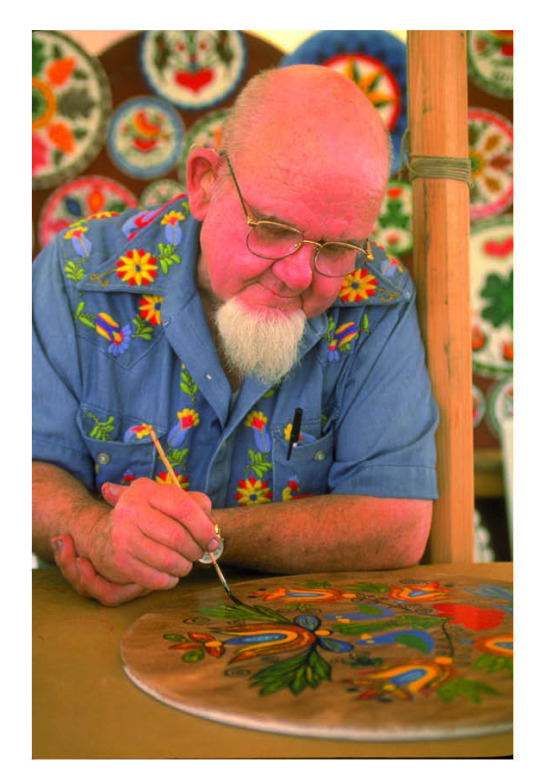

Jacob Zook, a screen printer, started selling disks with a predefined “meaning” and he along with two other hex sign painters in particular are most credited with changing how producers, consumers, and tourists understand hex signs. The two others are Johnny Ott, a self-proclaimed Hexologist from Berks County, and his protégé Johnny Claypoole.

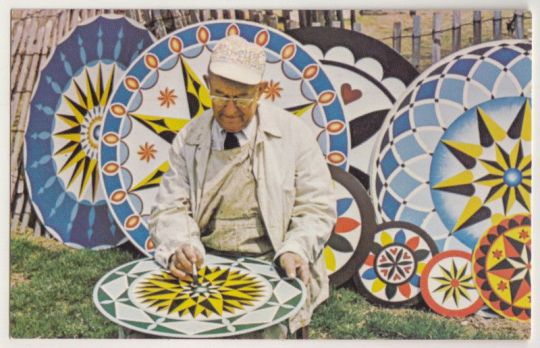

[Image description: Johnny Ott posing for a postcard in front of his collection of new, stylized “hex signs.”]

Ott was the first to really introduce motifs like birds and interlacing flowers which had been around in other PA Dutch folk art but had not been seen on barns. Ott also sold his work on disks instead of painting barns directly. He was a charismatic man who enjoyed telling tall tales about the magical properties of his work, even claiming that the Delaware River flood of 1958 was due to a farmer leaving his hex sign for rain and fertility out too long.

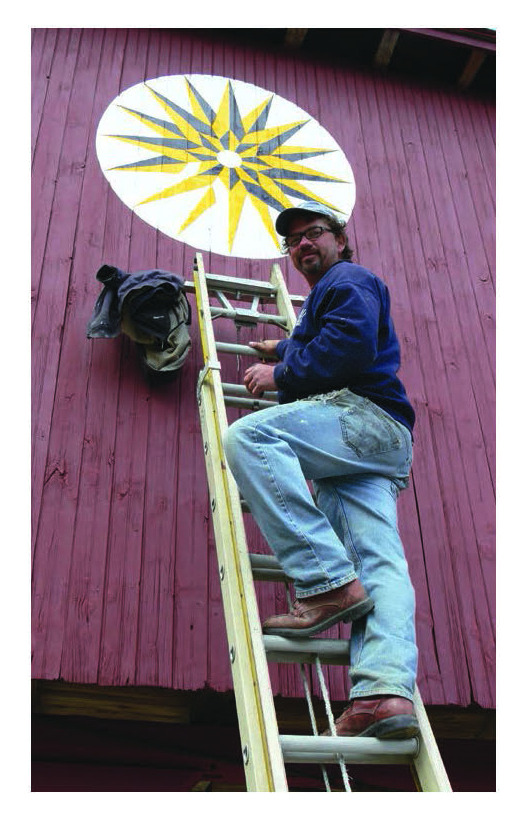

[Image description: Johnny Claypoole painting a hex sign, in front of a wall of his other art.]

Claypoole continued his mentor’s tales and stylized art but also painted barns directly, something Ott never did. In fact, Johnny Claypoole and his son Eric are responsible for repainting many of the aging stars in PA. The term “ghost stars” which refer to the weathered outlines of old barn stars is attributed to Johnny Claypoole and these ghosts are used as templates for repainting to maintain the local history and aesthetics.

[Image description: A weathered barn star “ghost,” salvaged from a once-decorated wagon shed in Windsor Castle, Berks County.]

[Image description: Eric Claypoole painting a barn star in the traditional style]

Conclusion: