#Oleg Kirov

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oleg Kirrov in Saints Row: The Third (2011)

#Crimson's Gifs: Saints Row#Saints Row#SR#Saints Row: The Third#SR:TT#Saints Row The Third#SRTT#Saints Row 3#SR3#Oleg Kirrov#Oleg Kirov#Oleg SR#Oleg Saints Row#My king I miss you

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mikhail Baryshnikov (dancer, born January 27, 1948, in Riga, Latvia) "Working is living to me,'' Mikhail Baryshnikov once said. He has worked hard and lived to the fullest. His name is synonymous with dance throughout the world. His dancing is a sublime vision at the dawn of a new century. Mikhail Nikolaevitch Baryshnikov was born in Riga in 1948 and began his ballet studies there in 1960. In 1964, he entered the Vaganova School in what was then called Leningrad, studying with the legendary Aleksander Pushkin and soon winning the top prize in the junior division of the International Varna Competition. Word began spreading of this extraordinary young dancer of precious classical purity and exquisite presence. Clive Barnes gave notice of what was to come after observing the student Baryshnikov in Pushkin's class, describing him as ""the mostemperfect dancer I have ever seen.'' He joined the Kirov Ballet and made his debut at the Maryinsky Theater in 1967, dancing the “Peasant” pas de deux in Giselle. Choreographers recognized in Baryshnikov a unique instrument for new dance, and soon Oleg Vinogradov, Konstantin Sergeyev, Igor Tchernichov, and Leonid Jakobson created ballets for him. Jakobson's 1969 Vestris, a feast of virtuosity and wit, became Baryshnikov's signature role and, along with his intensely otional Albrecht in Giselle, his calling card to his new home. Baryshnikov defected from the Soviet Union in 1974 in search for artistic and personal freedom in the West. He made his debut with the American Ballet Theatre that same year, dancing Giselle with Natalia Makarova. He stayed with ABT for the next four years, voraciously learning and defining new roles, expanding his horizons as well as those of male dancing. memorably, he also staged ABT's productions of The Nutcracker, Don Quixote and Cinderella. In 1978, Baryshnikov left ABT for New York City Ballet, where he could work with George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. He returned to ABT in 1980, not only as principal danceR&But also as artistic director, a distinguished position he held for almost a decade. In the years that followed, Baryshnikov's explorations of artistic frontiers became one of the most dazzling spectacles of the age: dances by Merce Cunningham and Erick Hawkins, the play Metamorphosis on Broadway, The Turning Point, White Nights and Dancers on screen, my Award-winning television specials with Twyla Tharp and Liza Minnelli, glittering galas for Martha Graham and Paul Taylor. Baryshnikov is a naturalized American citizen. In 1990, he teamed up with Mark Morris and founded the White Oak Project, a unique dance company that reflects Baryshnikov's passion for modern dance and bodies the extraordinary transformation of a paragon of Russian ballet into the very model of perfection in American modern dance. Not long after coming to the United States, Baryshnikov looked both back and ahead at the immense possibilities of a dancer's lifetime. "I have been very lucky to work in so many new ballets, but that is what a dancer's work is,'' he wrote in the 1978 Baryshnikov At Work. He likened the challenge of dancing different choreographies and styles to learning new languages, confessing that "there are never enough.'' He added that "every ballet, whether or not successful artistically or with the public, has given me something important. Everything that I've done has given me more freedom.'' Has anyone in the field of dance ever made so much of that freedom? The generosity of Baryshnikov's spirit braces the world. He has danced to Adam and Tchaikovsky, but also to Dmitri Shostakovich and Philip Glass, to Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra. He has danced to silence, and he has danced to his own heartbeat. He has been the ideal Albrecht and Prince Siegfried, but he has also stepped out in style as a paragon of jazz dancing. He has been, and continues to be, a surprise. He bodies so many different and impossibly beautiful things to so many people that it is next to impossible to define him save to say this: Mikhail Baryshnikov is a dancer.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Smiley's People - BBC Two - September 20, 1982 - October 25, 1982

Spy Drama (6 episodes)

Running Time: 360 minutes Total

Stars:

Alec Guinness as George Smiley

Eileen Atkins as Madame Ostrakova

Michael Byrne as Peter Guillam

Bernard Hepton as Toby Esterhase

Anthony Bate as Sir Oliver Lacon

Barry Foster as Sir Saul Enderby

Michael Lonsdale as Anton Grigoriev

Beryl Reid as Connie Sachs

Bill Paterson as Lauder Strickland

Siân Phillips as Ann Smiley

Mario Adorf as Claus Kretschmar

Tessy Kuhls as Frau Kretzschmar

Patrick Stewart as Karla

Curd Jürgens as Gen. Vladimir

Vladek Sheybal as Otto Leipzig

Rosalie Crutchley as Mother Felicity

Maureen Lipman as Stella Craven

Dudley Sutton as Oleg Kirov

Michael Gough as Mikhel

Michael Elphick as Detective Chief Superintendent

Paul Herzberg as Villem Craven

Stephen Riddle as Nigel Mostyn

Tusse Silberg as Alexandra/Tatiana

Norma West as Hilary

Ingrid Pitt as Elvira

Lucy Fleming as Molly Meakin

Andrew Bradford as Ferguson

Joe Praml as Paul Skordeno

Alan Rickman as Mr Brownlow

Tanya Rees as Beckie Craven

Alex Jennings as PC Hall

#Smiley's People#TV#Spy Drama#BBC Two#1982#Alec Guinness#Eileen Atkins#Curd Jurgens#Dudley Sutton#Michael Gough#Vladek Sheybal#Bill Patterson#Anthony Bate#Michael Elphick

1 note

·

View note

Text

Russia annexed Crimea comes under another drone attack

On the night of Saturday, August 12, explosions were heard in the annexed Crimea.

Eyewitnesses report that they heard a loud explosion in the Kirov district. Oleg Kryuchkov, an adviser to the Russian "head" of Crimea, said that air defense was active in different regions of Crimea.

At the same time, the official Telegram channel of the Kerch Bridge authority reported that the bridge was closed to traffic.

"The vehicle traffic on Source

0 notes

Photo

Andris Liepa in Oleg Vinogradov’s Petrushka (Kirov Ballet, 1990 [?])

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You see, the Bolshoi is very musical, they dance very well to music. But the Kirovsky is music itself.

Oleg Vinogradov

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

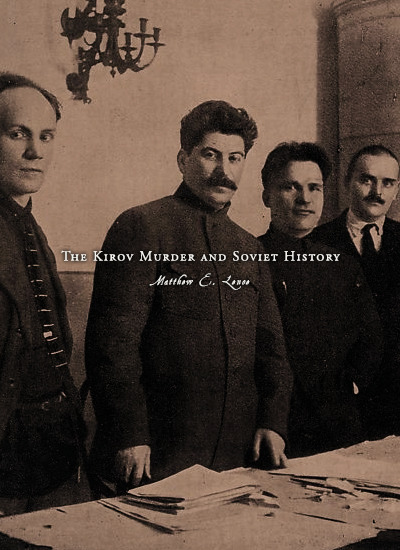

Favorite History Books || The Kirov Murder and Soviet History by Matthew E. Lenoe ★★★★☆

This book is in large part the story of how one of the greatest mass murderers of modern history, Joseph Stalin, made use of the fear and rage provoked by the Kirov murder to justify the execution or confinement in forced labor camps of millions of innocent people. In the months following the murder, Stalin did all he could to heighten the atmosphere of suspicion and dread that accompanied the killing. He warned of terrorist plots to assassinate the entire Soviet leadership, and proclaimed that no one could be trusted because “enemies” had penetrated the party itself. He focused at first on former “Left” Communists who had opposed his consolidation of power in the 1920 s. In Leningrad thirteen men, mostly former Left sympathizers, were framed, charged with plotting a terrorist attack on Kirov, and executed together with the actual assassin, Leonid Nikolaev. Two of Stalin’s most prominent former rivals, Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, were tried in January 1935 for “moral complicity” in the assassination and sentenced to long prison terms. Thousands of other former supporters of Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Stalin’s exiled archenemy Leon Trotsky were arrested and sent to concentration camps in the winter of 1934 – 1935 .

Following a year and a half of steady repression of former Left Communist opponents as well as the usual “class enemy” suspects, Stalin ramped up the attack on the remnants of the defunct Communist opposition groups. In August 1936 he organized the trial and execution of Kamenev and Zinoviev on charges of conspiring to murder Kirov, Stalin himself, and several other Soviet leaders. Then, in early 1937 , the security organs arrested the former leaders of the “Right Deviation,” a loose group of Communists who had opposed forced collectivization and Stalin’s domination of the party. The most prominent of these men, Nikolai Bukharin and Aleksei Rykov, were put on trial in March 1938 for terrorism, treason, and complicity in Kirov’s murder. They were subsequently executed. By the time of the March 1938 show trial, the Soviet Union was embroiled in a cataclysm of state-sponsored violence. Beginning in late June 1937 Stalin, in an apparent attempt to eliminate any possible source of resistance to his rule, presided over the execution of thousands of senior party officials who had no record of political opposition. Many of these men and women were charged with complicity in Kirov’s murder and/or conspiring to kill Stalin himself. The dictator and his closest associates also ran so-called “mass operations” in which the state security forces shot around 700,000 people, deporting or arresting millions more. Many of those arrested died of neglect and abuse in the forced labor camps. While the Kirov murder was not the direct pretext or the real motivation for the mass operations, the atmosphere of dread and hyper-vigilance that Stalin developed around the assassination facilitated them.

Stalin’s use of Kirov’s death to justify terror led by 1939 to conjectures in the West that he might have ordered the killing himself. Also, chewed-up fragments of rumors from the Soviet Union reached European socialists and fueled such speculation. Over the succeeding decades Western authorities on Soviet affairs and Soviet advocates of de-Stalinization accumulated many bits and pieces of evidence suggesting Stalin’s complicity in the crime. By the early 1970 s speculation had become certainty for Western scholars such as Robert Conquest and Soviet opponents of Stalinism like Roy Medvedev.

... Yet even before the archival gold rush attendant upon the fall of the Soviet Union, a few Western scholars voiced doubts that Stalin had conspired to kill Kirov. Most notably, J. Arch Getty in Origins of the Great Purges questioned the sources on which the received narrative was based. Getty noted that the NKVD defectors and émigrés who reported the various elements of the “Stalin did it” version were in fact passing on third-, fourth-, or more-hand rumors. He cast doubts too on oral history evidence gathered in the late 1950s and early 1960s during Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization drive, observing both the investigators’ political biases and the length of time elapsed since the crime. Finally, Getty reiterated Adam Ulam’s skepticism that Stalin would have resorted to such a risky expedient as political assassination to rid himself of Kirov. The Leningrad party chief, Getty argued, was no moderate rival to Stalin, but a loyal follower of second rank.

The opening of Soviet archives in the early 1990 s tended to strengthen Getty’s arguments. Two Russian scholars, Alla Kirilina and Oleg Khlevniuk, used newly available documents to debunk many of the received myths about the Kirov assassination. Khlevniuk, while agnostic about Stalin’s involvement in Kirov’s murder, assembled Central Committee documentation to demonstrate that the Leningrad party chief was never a rival to the Soviet dictator. Kirilina utilized Leningrad archives, Central Committee sources, and her own interviews with surviving witnesses to show that many details of the received narrative were simply false, and to argue that Leonid Nikolaev was probably a lone gunman.

#historyedit#litedit#sergei kirov#soviet history#russian history#european history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

Ralph Fiennes didn’t need a magic spell to bring gay ballet icon Rudolf Nureyev back to life. Instead, the actor/director relied on the talents of Ukrainian dancer-turned-actor Oleg Ivenko in dramatizing a pivotal chapter in Nureyev’s life: the months leading up to his 1961 defection from the Soviet Union at age 23 while he performed with the Kirov Ballet Company in Paris, had affairs with both men and women, and pissed off his oppressive KGB minders. Although famously arrogant, rude, and even abusive, the supremely talented and trailblazing dancer worked in London and Paris for three decades before he died from AIDS complications in 1993.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The White Crow (2019)

Rudolf Nureyev, a remarkable young dancer of 22, is a member of the world-renowned Kirov Ballet Company, travelling to Paris in 1961 for his first trip outside the Soviet Union. But KGB officers watch his every move, becoming increasingly suspicious of his behavior and his friendship with the young Parisienne Clara Saint. When they finally confront Nureyev with a shocking demand, he is forced to make a heart-breaking decision, one that may change the course of his life forever and put his family and friends in terrible danger.

Directed by: Ralph Fiennes

Starring: Oleg Ivenko, Ralph Fiennes, Adele Exarchopoulos, Raphael Personnaz, Sergei Polunin, Chulpan Khamatova, Louis Hofmann

Release date: March 12, 2019

#The White Crow#Ralph Fiennes#Oleg Ivenko#Adele Exarchopoulos#Raphael Personnaz#Sergei Polunin#Chulpan Khamatova#Louis Hofmann#Movie#Movie Trailers#Film

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The White Crow (2019)

Those unfamiliar with the world of ballet may not recognize the name Rudolf Nureyev. I had no idea who he was going into the film based on his life, The White Crow. The film will play best to those who already know he was an accomplished dancer who revolutionized the art form despite all odds. For the rest, it has both ups and downs.

Born on a Trans-Siberian train in the Soviet Union, Nureyev (Oleg Ivenko) began his dance career late but showed much promise right away. Quickly rising to be one of the Kirov Ballet’s most accomplished dancers, he never fit in with his country’s strict rules and regulations. A trip to France brings a new world to his attention and inspires within him a sudden desire for more.

Directed by Ralph Fiennes (who also plays the role of Alexander Pushkin, Rudolf’s principal instructor), I admire his willingness to show Nureyev warts and all. At numerous points, he’s impatient, arrogant and dismissive of others’ feelings, even those of people who are close to him like his girlfriend Clara (Adèle Exarchopoulos) or his other male and female lovers. He can be straight-up cruel, to the point you kind of wonder why we’re supposed to like him exactly. Then, you see him dance. Oleg Ivenko doesn’t seem to leap into the air as much as he glides through the space above the stage. He defies gravity. Even if you’re not familiar with the terms and techniques of the dances he’s performing, you immediately recognize his skills.

The film truly springs to life in a pivotal moment where Rudolf’ is on his way to the airport. There’s tension, uncertainty, danger, and all sorts of mixed emotions. Everything feels like it’s rushing by so quickly and yet so slowly you find yourself as overwhelmed as Rudolf. Before then, it's uneven. Told in a non-linear style for reasons that aren’t obvious to this viewer except perhaps to let us know something big is coming, the structure and certain events feel there either just because they actually happened - and not because they would help tell the story - or feel out of place - like they were created solely for the film and have no basis in reality. The movie’s in a can’t-win scenario because there just isn’t really that much going on. Despite the numerous scenes spent with Nureyev, you never quite develop a bond with him.

If Rudolf Nureyev is a subject of interest for you, this is an intimate portrait which covers a critical point in his life. You’ll be pleased to have seen it. If you’ve never heard of him, The White Crow may be worth checking out but I think at home is where it’ll play best. (Theatrical version on the big screen, July 3, 2019)

#The White Crow#The White Crow review#movies#films#reviews#movie reviews#film reviews#Ralph fiennes#David hare#Rudolf nureyev#Oleg ivenko#adele exarchopoulos#Chilean khamatova#Alexey morozov#2019 movies#2019 films#ballet

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

LUNDI 24 JUIN 2019 (Billet 2 / 3)

« NOUREEV » (2h 07 min)

Un film de Ralph Fiennes, avec Oleg Ivenko, Ralph Fiennes, Louis Hofmann, Adèle Exarchopoulos, Raphaël Personnaz…

Tout de suite vous dire que le film « Noureev » n’est pas parfait mais que l’histoire est passionnante et qu’on ne s’ennuie pas une seconde (pour peu qu’on aime le sujet).

Ce qui fait rire JM, c’est que les Critiques (avec un « C » majuscule) ont été assez sévères avec ce biopic. Ils le sont surtout quand ils sont réalisés par des metteurs en scène étrangers. Par contre, quand c’est un Français (Roschdy Zem) qui rate par exemple complètement celui du clown « Chocolat », le premier artiste noir de la scène française dans le Paris de la Belle Epoque… alors ils peuvent être d’une incroyable indulgence. Peur de dire du mal d’un film qui parle du racisme ? Et pourtant, on aurait pu en faire un biopic formidable et l’exporter dans le monde entier ! Donc ces Critiques (avec un grand « C ») sont très forts pour dire que « Noureev » est un biopic « conventionnel », trop « classique », etc. mais aucun d’entre eux - on a cherché dans tous les journaux et magazines français, aucun n’a dit qu’Adèle Exarchopoulos qui joue Clara Saint (celle qui a aidé Noureev pour qu’il demande au Bourget in extremis l’asile en France) est archi-nulle (dans ce rôle), qu’on se demande à chaque fois qu’elle apparait, comment se fait-il que Ralph Fiennes l’ait choisie. Dans ce film, si elle a de la présence, elle est ectoplasmique ! Raphaël Personnaz, autre acteur français « imposé » par la co-production anglo-française, même si son rôle est plus mince, est nettement meilleur, comme d’ailleurs devraient être a minima toutes les personnes qui jouent dans un film. Marina a été dérangée par le jeu mou et sans caractère du professeur de danse russe de Noureev, interprété par Ralph Fiennes. Etant donné que ce dernier est un immense comédien, ce doit être sûrement parce que le personnage l’était vraiment dans la vie. Mais tous les autres sont parfaits et particulièrement Oleg Ivenko qui joue le rôle de Noureev ! Il a 2 longs plans-séquences où il doit danser, virevolter et sauter comme Noureev, il le fait avec une technique époustouflante ! Le film avance en flashbacks permanents, ce n’est pas gênant du tout, contrairement à ce que certains ont écrit. Il nous a donné en tout cas l’envie d’en savoir encore plus sur ce génie de la danse et nous avons commandé le jour-même sur Amazon une biographie dont on a lu du bien : « Noureev » de Bertrand Meyer-Stabley (Editions Payot).

Vous trouverez ci-dessous une critique plutôt positive du film. Si vous aimez la danse... et plus particulièrement Noureev, nous vous le recommandons (la bande-annonce est très bien faite, ne la ratez pas).

Marina lui a donné ♥♥♥ et JM, ♥♥♥, 8 sur 5

______________________________

« En juin 1961, au pic de la guerre froide, le ballet du Kirov se produit à Paris, sur la scène de l’Opéra, où triomphe, dans « le Lac des cygnes », un danseur étoile de 23 ans. Suivi par les agents du KGB et guidé par Clara Saint (fiancée à un fils du ministre de la Culture André Malraux), le sanguin, ambitieux et puéril Rudolf Noureev tombe amoureux de la capitale française, ses artistes, ses nuits folles et sa liberté. Alors que le Kirov s’apprête, depuis Le Bourget, à s’envoler pour Londres, Noureev, à qui les autorités soviétiques ordonnent de rentrer à Leningrad, se jette, en plein aéroport, dans les bras de deux policiers français et demande l’asile politique : « Je voudrais rester dans votre pays. » L’épisode est connu. Le film de l’acteur britannique Ralph Fiennes n’apporte rien qu’on ne sache déjà. Le principal intérêt de ce biopic est de voir, dans l’impossible rôle de « Rudi », le danseur ukrainien Oleg Ivenko, de l’Opéra de Kazan. Il n’est pas seulement convaincant dans son jeu, il l’est aussi dans ses incroyables cabrioles, grands jetés et autres tours en l’air. Sans oublier le saut final vers l’Ouest. »

(Source : « lenouvelobs.com »)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oleg Kirrov in Saints Row: The Third (2011)

#Crimson's Gifs: Saints Row#Saints Row#Saints Row: The Third#Saints Row The Third#SRTT#SR:TT#Saints Row 3#SR3#Oleg Kirrov#Oleg Kirov#MY SWEET GENTLE GIANT KINGHGGG

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

•|•|•|•|•|•|•|•|•Mikhail Baryshnikov (dancer, born January 27, 1948, in Riga, Latvia) "Working is living to me,'' Mikhail Baryshnikov once said. He has worked hard and lived to the fullest. His name is synonymous with dance throughout the world. His dancing is a sublime vision at the dawn of a new century. Mikhail Nikolaevitch Baryshnikov was born in Riga in 1948 and began his ballet studies there in 1960. In 1964, he entered the Vaganova School in what was then called Leningrad, studying with the legendary Aleksander Pushkin and soon winning the top prize in the junior division of the International Varna Competition. Word began spreading of this extraordinary young dancer of precious classical purity and exquisite presence. Clive Barnes gave notice of what was to come after observing the student Baryshnikov in Pushkin's class, describing him as ""the mostemperfect dancer I have ever seen.'' He joined the Kirov Ballet and made his debut at the Maryinsky Theater in 1967, dancing the “Peasant” pas de deux in Giselle. Choreographers recognized in Baryshnikov a unique instrument for new dance, and soon Oleg Vinogradov, Konstantin Sergeyev, Igor Tchernichov, and Leonid Jakobson created ballets for him. Jakobson's 1969 Vestris, a feast of virtuosity and wit, became Baryshnikov's signature role and, along with his intensely otional Albrecht in Giselle, his calling card to his new home. Baryshnikov defected from the Soviet Union in 1974 in search for artistic and personal freedom in the West. He made his debut with the American Ballet Theatre that same year, dancing Giselle with Natalia Makarova. He stayed with ABT for the next four years, voraciously learning and defining new roles, expanding his horizons as well as those of male dancing. memorably, he also staged ABT's productions of The Nutcracker, Don Quixote and Cinderella. In 1978, Baryshnikov left ABT for New York City Ballet, where he could work with George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. He returned to ABT in 1980, not only as principal danceR&But also as artistic director, a distinguished position he held for almost a decade. In the years that followed, Baryshnikov's explorations of artistic frontiers became one of the most dazzling spectacles of the age: dances by Merce Cunningham and Erick Hawkins, the play Metamorphosis on Broadway, The Turning Point, White Nights and Dancers on screen, my Award-winning television specials with Twyla Tharp and Liza Minnelli, glittering galas for Martha Graham and Paul Taylor. Baryshnikov is a naturalized American citizen. In 1990, he teamed up with Mark Morris and founded the White Oak Project, a unique dance company that reflects Baryshnikov's passion for modern dance and bodies the extraordinary transformation of a paragon of Russian ballet into the very model of perfection in American modern dance. Not long after coming to the United States, Baryshnikov looked both back and ahead at the immense possibilities of a dancer's lifetime. "I have been very lucky to work in so many new ballets, but that is what a dancer's work is,'' he wrote in the 1978 Baryshnikov At Work. He likened the challenge of dancing different choreographies and styles to learning new languages, confessing that "there are never enough.'' He added that "every ballet, whether or not successful artistically or with the public, has given me something important. Everything that I've done has given me more freedom.'' Has anyone in the field of dance ever made so much of that freedom? The generosity of Baryshnikov's spirit braces the world. He has danced to Adam and Tchaikovsky, but also to Dmitri Shostakovich and Philip Glass, to Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra. He has danced to silence, and he has danced to his own heartbeat. He has been the ideal Albrecht and Prince Siegfried, but he has also stepped out in style as a paragon of jazz dancing, as a living bl of modern and post-modern sensibilities, as a choreographer and teacher, as a company director. He has been, and continues to be, a surprise.

0 notes

Photo

A Viewer's Guide to The White Crow, Ralph Fiennes' Rudolf Nureyev Biopic

I caught a preview screening of The White Crow earlier this week at New York City's 92Y, and I have to say: Even with a solid grasp of dance history and a smattering of film studies knowledge, I had some questions when the credits rolled. The Ralph Fiennes–directed Rudolf Nureyev biopic dramatizes the events leading up to the ballet star's famous defection from the Soviet Union, touching on incidents from his childhood and his years at the Leningrad Choreographic School.

The meaning of the film's enigmatic title, The White Crow, is explained straightaway. It's a Russian term for someone "unusual, extraordinary, not like others, an outsider." (Aside: Has anyone else noticed Hollywood's tendency to name ballet-adjacent movies with a color and a type of bird? Black Swan, Red Sparrow, The White Crow...)

The film unfolds across three intertwined timelines

The triple-timeline structure utilized by Fiennes and screenwriter David Hare (who is admittedly fond of the device) means that we as a viewer have to work a bit harder to piece together what's happening. There are three different time periods in play: Nureyev's childhood, which stretches from his birth on a train in 1938 through his mother dropping him off at his first ballet school; the Leningrad years, 1955–61; and the weeks in Paris leading up to his defection on June 16, 1961.

Even as the film intertwines the three strands, each one unfolds chronologically (with the exception of the bookended opening scene, which features the interrogation of Alexander Pushkin, played by Fiennes, after Nureyev's defection).

The triple-timeline structure utilized by Fiennes and screenwriter David Hare (who is admittedly fond of the device) means that we as a viewer have to work a bit harder to piece together what's happening. There are three different time periods in play: Nureyev's childhood, which stretches from his birth on a train in 1938 through his mother dropping him off at his first ballet school; the Leningrad years, 1955–61; and the weeks in Paris leading up to his defection on June 16, 1961.

Even as the film intertwines the three strands, each one unfolds chronologically (with the exception of the bookended opening scene, which features the interrogation of Alexander Pushkin, played by Fiennes, after Nureyev's defection).

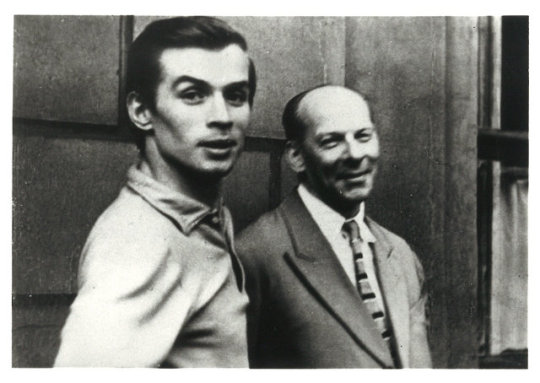

Who was Alexander Pushkin? A black and white photograph of a young Rudolf Nureyev and his teacher, Alexander Pushkin, here smiling and wearing a suit and tie. Rudolf Nureyev with Alexander Pushkin

Fiennes pulled double duty on the film, not only directing but also playing legendary ballet teacher Alexander Pushkin (not to be confused with the famed Russian writer). As a teacher at the Leningrad Choreographic School (as the Vaganova Ballet Academy was then known), Pushkin shaped the leading male dancers of the Kirov for decades—and Nureyev wasn't his only famous student. Mikhail Baryshnikov, who, like Nureyev, ultimately defected from the Soviet Union (in 1974), also trained under the master teacher. "This man made me as a dancer," Baryshnikov once said.

In a scene from The White Crow, Rudolf Nureyev stands at attention in a ballet uniform as his teacher, Alexander Pushkin, considers him. Behind them is a mirror, in which other male ballet students are standing at attention at the barre and an accompanist awaits instructions at his piano.

Nureyev (Ivenko) joins the class taught by Alexander Pushkin (Ralph Fiennes) in The White Crow.

Fiennes' depiction of Pushkin's approach aligns with his students' accounts. It was "a delicate way of teaching," Fiennes said at the screening, in which Pushkin would suggest ideas or simply ask a dancer to stop and repeat what they'd done to allow them to find and fix their own errors. Baryshnikov described Pushkin as "a very quiet man. A father figure, to us."

If the dance sequences look great (which mostly, they do), it's because of a former Royal Ballet star. In The White Crow, Rudolf Nureyev, costumed in a gold costume and tights, prepares to turn during a performance.

"I don't have any interest in ballet," Fiennes said at the screening, going on to say that he was drawn to the story by Nureyev's "ferocious sense of destiny" rather than his dancing. "I'm way out of my comfort zone," he added. Though he watched hours of archival footage of Nureyev's performances in preparation for filming, the director found himself frustrated by the way all of the footage only used wide angles to show the full body, and was eager to play with camera angles and close-ups during The White Crow's dance sequences.

However, Johan Kobborg, who was brought onto the film as both dance consultant and choreographer, convinced him that the scenes needed to be shot to show the dancers' full bodies, and that the camera should respect the "front" of the choreography. "The dancers are very sensitive to how they're being filmed," Fiennes said. "Johan Kobborg said to me, 'Well, it's okay, but it looks ugly to me because I'm showing you a specific angle.' " They ultimately reshot several of the dance sequences.

Who is the older ballerina who requests Nureyev as her partner? In the White Crow, Natalia Dudinskaya, an older, blonde ballerina, and Rudolf Nureyev rehearse in the studio. Both wear practice clothes and are posed in releve, arms in fourth position.

Natalia Dudinskaya (Anna Urban, née Polikarpova) and Nureyev (Ivenko) rehearse in a still from The White Crow.

Unless you just so happen to already know this key bit of Nureyev's Kirov career, it's unfortunately all too easy to miss this detail. When Nureyev graduated from the Leningrad Choreographic School, he got multiple contract offers but ultimately went to the Kirov, where he made his debut dancing opposite star ballerina Natalia Dudinskaya. She was in her late 40s and within a couple years of her official retirement; Nureyev was a 21-year-old fresh out of the academy.

In The White Crow, Nureyev asks Dudinskaya (portrayed by Anna Urban, née Polikarpova) why she requested to dance with him. "I'll make you look talented, you'll make me look young," is her wry reply. (We couldn't help but think that this comment was also meant as a nod to Nureyev's later famed partnership with Dame Margot Fonteyn.)

Yes, the actor playing Nureyev is a real dancer. As quickly becomes obvious during the film's dance sequences, the actor playing Nureyev is also an accomplished ballet dancer. His name is Oleg Ivenko, and he's a leading dancer at the Musa Dzhalil Tatar State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre Company. Much of Nureyev's technical prowess and pyrotechnics are considered par for the course for today's male dancers, but we were quite impressed by Ivenko's attention to detail—he even managed to recreate Nureyev's distinctive arabesque line. He might not have quite managed the peculiar alchemy that made Nureyev such an explosive performer, (who could?) but he did capture the famed dancer's "mischievous hauteur" (as Fiennes put it) in his interactions with the other characters.

In fact, there are lots of dancers playing dancers. In addition to Ivenko and Urban (who enjoyed an extensive career at Hamburg Ballet and now teaches at the company's affiliated school), the cast also includes Sergei Polunin (before his most recent spate of social media nastiness), Bolshoi soloist Anastasia Meskova and Belgrade National Theater first soloist Margaryta Cheremukhina.

Did Nureyev really have an affair with his teacher's wife? There are rumors that Nureyev and Xenia, Pushkin's wife, herself a former dancer, had an affair after the Pushkins invited the young Rudi to live with them. The affair is shown in the film, and while Hare is convinced that they did, it's impossible to prove or disprove.

It is worth noting that similar rumors dogged Nureyev's friendship with Fonteyn, and there is some strangeness in the fact that the film is more preoccupied with this alleged affair than it is with its nods to Nureyev's burgeoning awareness of his homosexuality. The film does seem to assert, however, that the realization of his own sexual orientation may have been one motivation for Nureyev to leave his situation with the Pushkins.

"Are you always this rude?" Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos), the French socialite who helped orchestrate Nureyev's defection, asks him this question in the film. The answer: quite often, yes, as demonstrated in multiple scenes in the film, and worse. Nureyev had a notorious temper—Dame Beryl Grey, who overlapped with him at The Royal Ballet, made headlines two years ago when her memoir detailed instances of the dancer behaving threateningly or violently toward dancers who displeased him. On the flip side, he could be incredibly charming and sweet—like everyone else, Nureyev contained multitudes.

Easter egg: Natalia Makarova's name appears on a casting sheet. It's a there-and-gone moment near the beginning of the film: Nureyev checks the opening night casting sheet in Paris to find his name not listed. But a few lines down? There's Natalia Makarova. Though she sadly does not appear as a character in the film, we love that the filmmakers included a nod to the ballerina—especially since she defected nearly a decade after Nureyev and landed at American Ballet Theatre.

youtube

https://www.dancemagazine.com/white-crow-nureyev-biopic-guide-2635456679.html?rebelltitem=1#rebelltitem1

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kirov Academy, a Leading Ballet School, to Close in May

The school, founded by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon more than three decades ago, told parents that the closing was related to financial issues.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/08/arts/dance/kirov-academy-ballet-school-closing.html

A winter recital performance of “The Nutcracker,” in 2019, at the Kirov Academy of Ballet. The future of the Kirov Academy’s building remains uncertain. Credit... Josh Jeong/Kirov Academy of Ballet

By Rebecca J. Ritzel Feb. 8, 2022 The Kirov Academy in Washington D.C., an elite ballet school founded by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, leader of the Unification Church, plans to close in May after serving as an important dance training ground for three decades. Parents were informed by email in November that the school was winding down its operations.

“As much as we love the Kirov Academy, we cannot ignore the financial reality,” the Kirov’s executive director Pamela Gonzales de Cordova wrote in the email.

...

Thomas Walsh, the president of the academy and the Universal Peace Federation, founded by Rev. Moon, said in an email: “Last year, it became clear that we could no longer rely on the necessary funding we had received in the past. We made great effort to acquire adequate funds to remain open for one more year so that we could help assure a smooth, dignified transition for our students, as well as faculty and staff.”

...

Tatiana Moon, Rev. Moon’s oldest daughter, had led the academy as president from 2018 until last July.

...

Rev. Moon opened the Kirov in 1990, 36 years after he founded the Unification Church. The religious movement is best known for its mass weddings, business ventures, conservative politics and longtime devotion to Rev. Moon, a self-proclaimed messiah who died in 2012.

His interest in ballet was fueled by his friendship with Hoon Sook Pak, a ballerina and the daughter of a close aide, Bo Hi Pak, who led The Washington Times as its president. In 1984, Hoon Sook Pak was on tour with the Washington Ballet and preparing for the lead role in “Giselle,” when Rev. Moon’s 17-year-old son ran his car off the road. Having died single, he was not eligible to enter heaven under the church’s teachings, so Hoon Sook Pak agreed to marry the dead teen’s spirit in a lavish ceremony in which she carried his portrait.

Later that year, Rev. Moon created the Universal Ballet company, in which Hoon Sook, who took the name Julia Moon, became a principal dancer. Six years later, a palatial-looking former monastery near Catholic University reopened as the Kirov Academy.

...

After Oleg Vinogradova (the Kirov Ballet’s first artistic director) died in 2008, church subsidies dwindled. In Seoul, the Moon and Pak families opened the Universal Ballet School, lessening the need to send dancers to Washington. “Over the years, they stopped putting money into the Kirov and stopped caring about it,” said Martin Fredmann, who served as artistic director from 2011 to 2013.

The closure comes less than a year after Sophia Kim, a former bookkeeper at the Kirov, was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in federal prison for bank fraud after being charged with embezzling more than $1.5 million from academy coffers. ...

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/08/arts/dance/kirov-academy-ballet-school-closing.html

A version of this article appears in print on Feb. 9, 2022, Section C, Page 3 of the New York edition with the headline: Kirov Academy to Close Its Elite Ballet School in Washington.

2013 Ex-nonprofit bookkeeper sentenced to two years for tax crimes

A former McLean resident who embezzled more than $800,000 from a nonprofit tied to the Unification Church and then failed to report the income on her tax returns was sentenced to two years in prison, prosecutors said. Sookyeong Kim Sebold, the former bookkeeper of the nonprofit, was sentenced to the prison time on Friday and was also ordered to pay $133,548 in restitution to the Internal Revenue Service.

_________________________

A Ballet School Rehired an Embezzler. Then $1.5 Million Vanished. New York Times March 16, 2020

Former Dance School Comptroller Pleads Guilty in $1.5 Million Fraud New York Times May 9, 2021

0 notes

Photo

Mikhail Baryshnikov in Oleg Vinogradov’s The Mountain Girl (Kirov Ballet, 1968)

#ballet#ballet history#mikhail baryshnikov#kirov ballet#mariinsky ballet#the mountain girl#oleg vinogradov

23 notes

·

View notes