#Office of the Chief Justice - www.ojp.gov

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Amazon Web Services Programme 2022

Amazon Web Services Programme 2022

Office of the Chief Justice has various vacancies open in the field of Administration Clerk, Registers Clerk, Typist and Usher Messenger. FAQs: “What Does the Office of Justice Programs Do, Office of Justice Programs Address, Lord Chief Justice Contact Details, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs Jobs, Lord Chief Justice List, Lord Chief Justice Email Address” Office of the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

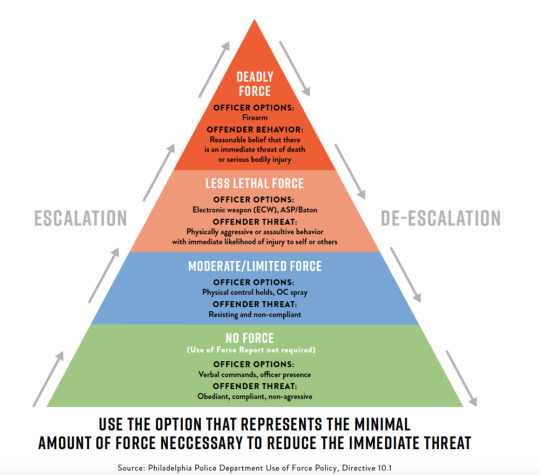

Ethics in Law Enforcement-USE OF FORCE

In relation to the universal definition of the use of force, there isn't an institutionally accepted one, however, The International Association of Chiefs of Police has described the use of force as the "amount of effort required by police to compel compliance by an unwilling subject". With this stated, it can be inferred that it is within the discretion of the officer, and guidelines are given by their respective agencies, to use whatever “force” or pressure they see fit to apprehend an individual.

A major problem that has been plaguing Jamaican officers over the years is the use of force. This is littered through the media as several videos have been posted showing instances in which officers were deemed to be using excessive force. The reality with this is that onlookers aren’t privy to both sides of the story and are quick to condemn the officers, thus siding with the civilian. This is due to the gross level of disrespect that is meted out to officers in this country, which is the ramification of an aloof relationship between citizens and law enforcers.

In Jamaica, the Constabulary Force Act speaks on various facets of the Force, in particular, its personnel and their policies, including but not limited to procedures and interactions with the public. In this particular document, there is not a specific clause that speaks to the use of force however Part I sections 15 through to 18 speaks on the power of arrests and the surrounding circumstances. With the absence of such a rule, there are calls for a reformation of this act to include such. There is such a clause presented in the JCF Human Rights and Police Use of Force and Firearms policy which is an underpublicized document dictating as the title suggests. Though this is the reality, there needs to be more integration of this policy into the actual Constabulary Force Act.

The general strain theory speaks to the use of force as being influenced by several factors including work and home stress, societal pressure ad social inclusion. Due to these factors officers of the law are more inclined to use excessive force due to these social strains.

Recommendations

Pre-employment screening

On the job counselling

Constant monitoring

2 strike policies

References

Scrivner, E. M. (1994). Controlling Police Use of Excessive Force: The Role of the Police Psychologist. National Institute of Justice-Research in Brief. Retrieved April 20, 2021, from https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/150063NCJRS.pdf.

0 notes

Text

Prosecutorial Discretion

By Laila Mustafa, Florida State University of 2022

March 5, 2021

When one imagines a courtroom, they may envision a room filled with rows of spectators and court reporters, a team of attorneys on either side, with a bench area facing outward, where the judge sits and passes down their sentences. Due to their prominence in court proceedings, many may argue that the judge is the most powerful member of the courtroom workgroup. Proponents of this argument may be failing to recognize the amount of discretion that prosecutors have throughout the criminal justice process. Prosecutorial discretion is the decision-making power prosecutors have based on the range of choices available to them that include scheduling cases for trial and negotiating plea deals and affects the results of many criminal proceedings.

Before a case is brought to trial, prosecutors are already faced with one of their most important displays of influence that ultimately controls the outcome of all criminal cases, the power to decide whether to charge the defendant with the offense [1]. When making this call, the prosecuting attorney has several things to mull over. They must evaluate their doubt that the accused is guilty, consider the strength of the case, and, as the attorney that serves the public interest, assess the harms caused by the offense. Once this judgement is made, the prosecutor makes a recommendation regarding pretrial release or detention that is dependent upon the defendant’s perceived risk to society, and the plea-bargaining negotiations commence.

Through plea deals, prosecutors can drop charges and reduce sentences if the defendant pleads guilty; this is a very attractive offer to those that fear going to court and receiving a guilty verdict. Although defendants can counter the offers, the prosecutors are the ones that must agree to its terms. Defendants plead guilty in 95% of all criminal cases through plea-bargaining [1]. As a result of their power to propose and accept plea deals, prosecutors can get a conviction without having to go to trial. The prosecution also decides the charges that are going to be brought against the defendant and whether they are going to be filed separately or simultaneously. When filing multiple charges at one time, prosecutors save time and money by presenting an extensive amount of evidence in one trial, while filing separate charges gives the prosecution more attempts to get a guilty verdict.

Although the prosecution determines the strength of the incriminating evidence during trial preparation, there are two important U.S. Supreme Court decisions that have made it prosecutors’ responsibility to make all evidence available to the defense. In the 1963 case Brady v. Maryland, the Court ruled that “suppression by the prosecution of evidence favorable to an accused who has requested it violates due process” [2]. The Court goes further in the 1985 US v. Bagley case, holding that the prosecution must release any evidence that the defense requests even if its disclosure would not support claims of innocence nor guilt, or have an effect on the verdict [3].

After conviction, prosecutors can make sentencing recommendations to the judge. When making these recommendations, they consider several factors, such as the type of sentences that reflect the seriousness of the crime, and the need for the defendant to provide restitution to the victims. Despite there being advisory guideline ranges that “reflect an appropriate balance of factors” when making sentencing recommendations, it is up to the prosecution’s discretion whether to depart from the guidelines and obtain supervisory approval if they conclude that a sentence above or below the guideline range would better serve the public’s interest [4].

Once convicted, the prosecution also can exercise their discretion during the corrections stage of the criminal justice process by recommending whether the defendant be considered for early release from prison or parole. Like sentencing guideline ranges, there are guidelines that indicate the average time needed to serve in prison before being granted early release. Prosecutors can make decisions outside the guidelines where they feel the circumstances warrant. For example, the defendant’s age at the time of offense may serve as a mitigating factor that the prosecution assesses. Aggravating factors like salient factor scores that indicate that there is a high risk of parole violation must also be evaluated [5].

When discussing the amount of power prosecutors have throughout the criminal justice process, it is also important to note the immunity against liability they are granted when exercising their duties. Three Supreme Court cases can be used to examine this. The Supreme Court ruled in the 1976 case Imbler v. Pachtman that prosecutors are immune from liability for actions done in their capacity as prosecutors representing the State’s case. Burns v. Reed was an interesting case in 1991 where prosecutors recommended that the police use hypnosis when investigating Cathy Burns, who, when under hypnosis, confessed to the murders of her sons. The Court held that “giving advice to the police does not entitle a prosecutor to absolute immunity from civil law suits” [6]. Lastly, in the 2009 case Van de Kamp v. Goldstein, the U.S. Court of Appeals found that the actions by the prosecutors of obtaining information from a jailhouse informant in exchange for reduced sentences was administrative rather than prosecutorial, therefore it is not subject to immunity [7]. With these cases in mind, prosecutors are absolutely immune from liability in civil suits when their actions are judicial and associated with their role as an officer of the court.

Due to the amount of discretion prosecutors possess, there are many opportunities for prosecutorial misconduct. To combat such behavior, the Professional Misconduct Review Unit was created and is responsible for “all disciplinary and state bar referral actions” relating to Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) findings of “professional misconduct against career attorneys” [8]. Prosecutors are also expected to follow the Model Rules of Professional Conduct outlined by the American Bar Association (ABA). The ABA expects prosecutors to be committed to their primary duty of seeking justice within the bounds of law, and not just focus on getting a conviction [9]

______________________________________________________________

[1] https://journals.openedition.org/droitcultures/1580?lang=en

[2] https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/373/83/

[3] https://www.oyez.org/cases/1984/84-48

[4] https://www.justice.gov/jm/jm-9-27000-principles-federal-prosecution#9-27.730

[5] https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/uspc/legacy/2010/08/27/uspc-manual111507.pdf

[6] https://www.ojp.gov/library/abstracts/prosecutor-immunity-impact-burns-v-reed

[7] https://www.oyez.org/cases/2008/07-854

[8] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-creates-professional-misconduct-review-unit-appoints-kevin-ohlson-chief#:~:text=The%20Professional%20Misconduct%20Review%20Unit,professional

[9]

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/criminal_justice/standards/ProsecutionFunctionFourthEdition/

0 notes