#Nicholas of Cusa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What would have happened if what lived in the hearts of the greatest individuals – Nicolaus Cusanus, Paracelsus, Agrippa, Giordano Bruno, and Campanella – would have entered the hearts of everyone? […] What if the old and the new had met and intermingled, spirit with blood, and blood with spirit?

— Gustav Landauer, Revolution and Other Writings: A Political Reader, transl Gabriel Kuhn, (2010)

#German#Gustav Landauer#Revolution and Other Writings: A Political Reader#Gabriel Kuhn#(2010)#Nicolaus Cusanus#Nicholas of Cusa#Paracelsus#Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa#Giordano Bruno#Tommaso Campanella#What if? What if? What if...

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irrefutable proof that Jordan Peterson is a time traveler

#jordan peterson#lobster#12 rules for life#Nicholas of Cusa#theology#negative theology#postmodernism#renaissance

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Nicholas of Cusa, also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus, was a German Catholic cardinal and polymath active as a philosopher, theologian, ju...

Link: Nicholas of Cusa

0 notes

Text

another attempt at drawing @the-whispers-of-death oc Stone

art consistency? we don't know her.

(i feel like i could've done better for the scars)

#my post#my art#art#traditional art#oc is not mine#he belongs to: @the whispers of death#drew this during my new age philosophy lecture#Nicholas of Cusa is just not as interesting as the treat that is Stone#please be kind#fanart

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

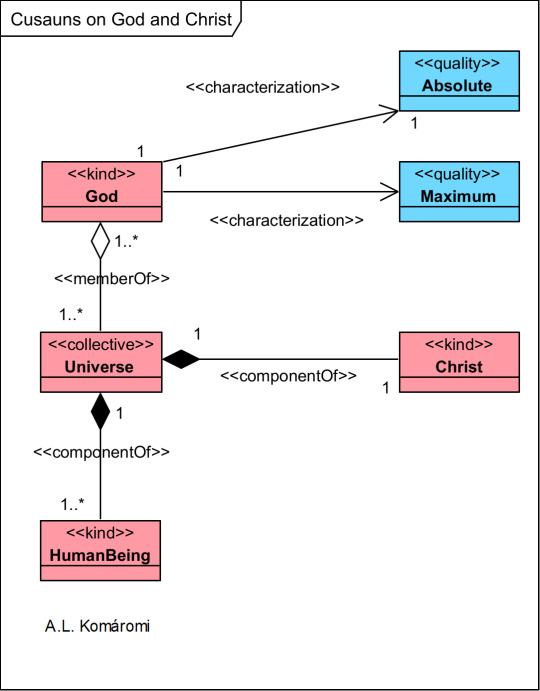

[6.10.1] Cusanus, Nicolaus on God, Universe, Christ, and Human Being

Nicholas of Cusa (Nikolaus Cryfftz or Krebs in German, then Nicolaus Cusanus in Latin, 1401-1464) “Christian Neoplatonic framework to construct his own synthesis of inherited ideas”. Cusanus addresses the four categorical realities traditionally found in Christian thought: God, the natural universe, Christ and human beings. God is absolute and maximum. The following OntoUML diagram shows…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

me observing Nicholas of Cusa’s commentary on Euclid’s Elements and his mathematical proofs of God (i barely understand any of it but i agree with him)

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think it would be possible for an Evangelical or Pentacostal church to enter full communion with Rome (presuming that their pastors would get ordained etc) while keeping most of its current liturgy?

I haven't really been to any Protestant services of a low church persuasion before, so I don't think I can competently comment on it. But in principle, I don't see why not.

In Allatae sunt, Pope Benedict XIV says that when groups of "schismatics" return to the Catholic Church, they should not be expected to give up their liturgical traditions. "[The Church's] great desire is [...] in short, that all may be Catholic rather than all become Latin." Now, this was written with the Orthodox Churches in mind. But I don't see why this would ipso facto mean that it couldn't also be applied to groups born of the Protestant Reformation.

Now, Anglican Ordinariate communities are technically Roman Rite Catholics, but their breviary and missal might bring something to the conversation, too. Namely, as their website says, Divine Worship: The Missal is a very unique Catholic liturgical text in that it "marks the first time the Catholic Church has sanctioned liturgical texts deriving from the Protestant Reformation." And if it's happened once, well, I don't see why it can't happen again. I would imagine that any explicitly anti-Catholic or overtly Calvinistic language would need to be expunged, and the Communion prayer would need to incorporate the Epiclesis and Words of Institution, at minimum.

Based off of these two principles, I don't think it's necessary impossible for what you're suggesting to come to pass. I think these rites would potentially look radically different from the current 24 rites of the Catholic Church, but as early as the 1450s, Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa was making suggestions for incorporating religious traditions that would have looked radically different from the Catholic rites prominent in his own time.

But I wonder if someone has actually talked about this possibility in a way that was publishable in an academic environment?

#asks#Christianity#Catholicism#ecumenicism#Allatae sunt#Pope Benedict XIV#Evangelical Christianity#liturgy#Ordinariate#Nicholas Cusanus#Protestant Reformation

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

All Time is Present

“All time is comprised in the present or ‘Now’.

The past was present, the future shall be present, so that time is only a methodical arrangement of the present.

The past and the future, in consequence, are the development of the present; the present comprises all present times, and present times are a regular and orderly development of it: only the present is to be found in them.

The present, therefore, in which all times are included, is One: it is Unity itself.”

- Nicholas of Cusa.

Image by Alex Grey.

23 notes

·

View notes

Quote

To answer these and other questions, Christian postliberals would draw less from Augustine and Aquinas—the gloomy Guses of inherited guilt, predestination, and infernalism—and more from figures such as Gregory of Nyssa and Nicholas of Cusa. Gregory’s eloquent and ferocious condemnation of slavery is one of the most extraordinary moral documents of antiquity, and he rooted his call for abolition not in a political metaphysics of rights but in theosis, an eschatological vision of humanity fully restored to its divinity. (“For how many obols did you value the image of God?”—a question that could well be posed to Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk.) Nicholas, whose work is witnessing a long overdue and hopefully permanent revival, is perhaps the theological avatar of a Christian commitment to innovative, democratic agency: the first theologian to explicitly contend that all governance stems from the consent of the governed, he also wrestled with the problem of how an evolving, multifarious universe, pliable to the art and technics of culture and civilization, could still be a manifestation of the divine.

Toward a Christian Postliberal Left

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Happened Today in Christian History

September 21, 1451: Nicholas of Cusa, a German cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, orders Jews to wear a yellow badge. A practice later followed by the Nazi regime throughout Germany and Nazi occupied Europe during the Second World War.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biblical Critical Theory has a quote from Nicholas of Cusa at the beginning, but I glanced at the footnote and thought it was Nic Cage and I don't quite have words for the emotion I felt in that half second

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

About

Autodidact, passionate intellectual. INFP, 5w4. Male (he/him), married, age 55. Currently living in New York state. I would describe my faith (i.e. an ontological orientation) through the lens of a critical post-Christian humanism, rooted in the Christian contemplative apophatic tradition.

Essential influences include: Byung-Chul Han, Simone Weil, T.S. Eliot, Maggie Ross, Iain McGilchrist, Evelyn Underhill, Owen Barfield, Hannah Arendt, Rainer Maria Rilke, Denise Levertov, David Bentley Hart, Sarah Coakley, Martin Buber, Kathleen Raine, Søren Kierkegaard, Meister Eckhart, Nicholas of Cusa, Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius, Laozi, Zhuangzi, J.S. Bach, Arvo Pärt, Akira Kurosawa, and Andrei Tarkovsky.

Some personal interests: poetry, philosophy, theology, literature, poetics, the history of ideas, etymology, art, film, classical music, and long, solitary saunterings in the woods.

—JMS, 2025

1 note

·

View note

Text

nicholas of cusa is the most awesome and important person to live in all of the middle ages, except for mechthild

rilke is the most awesome and important person to live in Germany, except for mechthild

these are the 3

father, mechthild

son, nicholas

spirit, rilke

0 notes

Text

As part of their programming for PST: Art & Science Collide, Getty Museum is showing Lumen: The Art & Science of Light. The exhibition includes a collection of European medieval artwork, along with several contemporary works, that focus in some way on the science and concept of light.

From the museum about the show-

Through the manipulation of materials such as gold, crystal, and glass, medieval artists created dazzling light-filled environments, evoking, in the earthly world, the layered realms of the divine. To be human is to crave light. We rise and sleep according to the rhythms of the sun, and have long associated light with divinity. Focusing on the arts of western Europe, this exhibition explores the ways in which the science of light was studied by Christian, Jewish, and Muslim philosophers, theologians, and artists during the “long Middle Ages” (800-1600 CE), when science and religion were firmly intertwined. Natural philosophy (the study of the physical universe) served as the connective thread for diverse cultures across Europe and the Mediterranean, uniting scholars who inherited, translated, and improved on a common foundation of ancient Greek scholarship.

This story is equal parts science, poetics, and craft. By bringing together a variety of media that materialize light and objects that communicate how medieval people understood the lights of the heavens and of the eye, this exhibition demonstrates how science informed the artistry of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. To convey the continuing sense of wonder inspired by starry skies or moving light on precious materials, the exhibition includes several contemporary works of art placed in dialogue with historic objects.

Below are a few selections-

“On the Construction of the World”, in “Book of Divine Works (Liber divinorum operum)” (text in Latin), Rupertsberg, Rhineland, Germany, about 1210-40 CE by Hildegard of Bingen (German, 1098-1179 CE), Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment

About this work from the museum-

The nun and philosopher Hildegard of Bingen is known for her deeply religious visionary experiences in which she communed with the fiery “living light” (lux vivens) of God. Yet her evocative spiritual imagery reflects the language of science and cosmology. Shown at lower left, Hildegard, an illuminator as well as author, recorded her dazzling vision of the human at the center of nested elemental spheres. The figure is ringed by heavenly bodies, the clouds, and the winds, all encircled by the figure of flaming Caritas, or Divine Love. As a way to understand humankind’s relationship to the Godhead, Hildegard’s imagery emphasizes the correspondence between the body and the cosmos; just as the four humors affected health, the four winds controlled the earth, and the vivifying power of divine light nourished both.

“The Glorification of the Virgin”, attributed to Geertgen tot Sint Jans, Haarlem, northern Netherlands, about 1490-95 CE, Oil on panel

The painting above by Geertgen tot Sint Jans has so many fascinating details and was part of a section titled Divine Darkness.

The wall text from that section-

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam all associate God with light. In the Creation story told in Genesis, when light was created, so too was darkness. As medieval optical theorists understood that sight was contingent upon light and that bodily vision was not possible in darkness, theologians of the time equated the unknowable, invisible aspects of God with darkness. According to a medieval “negative theology,” God exists beyond human perception and poses a challenge to vision itself. The fifteenth-century Christian theologian Nicholas of Cusa wrote that “God is found when all things are left behind; and this darkness is light in the Lord.” Such contradictory associations between God and both light and darkness were fundamental to the verbal and visual expressions used to elucidate the nature of the divine.

And about the painting-

Golden light surrounds the glorified Virgin Mary and Christ child at the center of this intimate and absorbingly detailed devotional painting as a luminous host of angels fills the heavens with eternal music. Their brightness contrasts with the dark perimeter that envelops this apocalyptic vision to suggest the ineffable darkness in which God dwells.

Constellations from a Hebrew Translation of Ptolemy’s “Almagest”, In an astronomical anthology (text in Hebrew), Catalonia, about 1361 CE, Tempura, gold, and ink on parchment and Astrolabe (with Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic Script), Iberia (Spain) or Italy, 1300s CE

From the museum about these two items-

In the Muslim and Christian courts of Europe, and particularly in Iberia, highly educated, multilingual Jews held important positions as physicians and astrologers. Jewish practitioners of these related fields contributed original works on astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy, drawing from and improving on Greco-Arabic sciences. At left, the Hebrew translation of Ptolemy’s Almagest (a work that was little known in Europe before 1200) updated the ancient text with the addition of astronomical tables that guided religious observance. Only a small number of European astrolabes with Hebrew inscriptions survive. This exquisite example lists the names of twenty-four stars in a combination of Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic. The centermost circle marks the ecliptic, or the sun’s path, and is labeled with the zodiacal signs in Hebrew.

“Untitled (Mugarnas)”, 2012, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Mirrors, reverse-glass painting, and plaster on wood

One of the most impressive contemporary pieces in the show was the sculpture pictured above, by Monir Sharoudy Farmanfarmaian, which captured and reflected light so beautifully.

About the work from the museum-

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian was deeply inspired by a visit to the Shah Cheragh shrine in Shiraz, Iran. The vaulted domes and walls of that site are covered in dazzling, intricate mirror mosaics that fracture and dematerialize space while reflecting light and amplifying movement and activity in the shrine below. Farmanfarmaian began exploring these mosaic techniques, eventually collaborating with master artisans to produce sculptural and wall-mounted works that incorporate mirror mosaic and reverse-glass painting. Untitled (Mugarnas) adopts the sacred and decorative forms that are common in Islamic architecture, and expresses the perfection of creation.

This exhibition closes 12/8/24.

#The Getty#Getty Museum#Medieval Art#Art#Art Shows#Book Art#Books#Geertgen tot Sint Jans#Getty Center#Pacific Standard Time Art and Science Collide#Hildegard of Bingen#Illustration#Los Angeles Art Show#Los Angeles Art Shows#Manuscripts#Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian#Pacific Standard Time 2024#Painting#PST#Science and Art#Sculpture#Religious Art

1 note

·

View note

Text

Continuity and Rupture in the Long Middle Ages

https://justifiable.fr/?p=1951 https://justifiable.fr/?p=1951 #Ages #Continuity #Long #Middle #Rupture Présentation de l’éditeur The “Long Middle Ages” indicates a span of time extending from Antiquity, across the Middle Ages, to the Early Modern period. The author tries to understand factors of historical continuity binding this period together and the periodic scenes of violent change that disrupted societies and traditions. The Long Middle Ages were established on classical and biblical foundations, while each generation interpreted and expanded on those origins. The cohesion of the Long Middle Ages was brought about by continuous acts of reflection and renascence. Scholarly practices and ideas of Antiquity were taken up in the monasteries and cathedral schools of the Middle Ages, while during the Renaissance, and then the Baroque period, thinkers looked back to Antiquity and to the Middle Ages. Continuity and Rupture in the Long Middle Ages is an interdisciplinary approach to intellectual history, which puts the history of ideas in the context of cultural, political, religious, and legal history. Medieval history is the central moment, while continuity and change are found in traditions extending from the Lord’s Prayer (AD 30) to Jean Mabillon (AD 1632–1707) and onward to moderns like Ernst Cassirer and Paul Ricoeur. Readers will discover new significance in historical figures like the Venerable Bede, Boniface of Mainz, Charlemagne, and Pope Formosus – in the laws of medieval kings and bishops – and institutions like the monastery of Cluny. These essays, gathered together for the first time in this Variorum volume, offer powerful new interpretations for students and researchers in the fields of medieval studies, legal and literary interpretation, legal history, and the history of European intellectual life from ancient to modern times. Michael Edward Moore is Emeritus Associate Professor of Medieval and European History, University of Iowa. He has published numerous essays on political culture and European intellectual history. He is the author of A Sacred Kingdom: Bishops and the Rise of Frankish Kingship and Nicholas of Cusa and the Kairos of Modernity. Born in Nuremberg, Germany, Moore was raised in New England and later among the woods and farmland of his native Michigan. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan where he studied with Hans Küng and Czeslaw Milosz. He enjoys canoeing and hiking in the wilderness. Sommaire Introduction Part I: Religion 1. Demons and the Battle for Souls at Cluny Originally published as: “Demons and the Battle for Souls at Cluny.” Studies in Religion / Sciences réligieuses 32.4 (2003): 485-497. Reprinted by permission of Sage Journals. 2. Bede’s Devotion to Rome: The Periphery Defining the Center Originally published as: “Bede’s Devotion to Rome: The Periphery Defining the Center.” Bède le Vénérable entre tradition et postérité. Edited by Stephane Lebecq, Michel Perrin et Olivier Szerwiniack. Lille: CEGES, 2005. 199-208. Reprinted by permission of Université Lille, CEGES. 3. The Frankish Church and Missionary War in Central Europe Originally published as: « The Frankish Church and Missionary Warfare in Central Europe. » Between Sword and Prayer: Warfare and Medieval Clergy in Cultural Perspective. Edited by Radoslav Kotecki, Jacek Maciejewsky, Jon S. Ott. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2017. 46-87. Reprinted by permission of E.J. Brill – Leiden. 4. The Attack on Pope Formosus: Papal History in an Age of Resentment Originally published as: « The Attack on Pope Formosus: Papal History in an Age of Resentment (875-897). » Ecclesia et Violentia: Violence Against the Church and Violence Within the Church in the Middle Ages. Edited by Radoslav Kotecki and Jacek Maciejewski. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014. 184-208. Reprinted by permission of Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 5. The Body of Pope Formosus Originally published as: “The Body of Pope Formosus.” Millenium. Jahrbuch zu Kultur und Geschichte des ersten Jahrtausends n. Chr. / Yearbook on the Culture and History of the First Millenium C.E., 9 (2012): 277-297. Reprinted by permission of Walter de Gruyter Academic Publishing. Part II: Law 6. Carolingian Monarchy and Ancient Irish Models of Kingship Originally published as: “La Monarchie carolingienne et les anciens modeles irlandais.” Annales – Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 51 (1996): 307–324. Translated into French by Alain Boureau. Reprinted by permission of Éditions de l’EHESS, Paris. 7. The Ancient Fathers: Christian Antiquity, Patristics and Frankish Canon Law Originally published as: « The Ancient Fathers: Christian Antiquity, Patristics and Frankish Canon Law. » Millenium. Jahrbuch zu Kultur und Geschichte des ersten Jahrtausends n. Chr. / Yearbook on the Culture and History of the First Millenium C.E., Vol.7 (2010): 293-342. Reprinted by permission of Walter de Gruyter Academic Publishing. 8. Canon Law and Royal Power in the Councils and Letters of St. Boniface Originally published as: “Canon Law and Royal Power in the Councils and Letters of St. Boniface.” The Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law 28 (2008) [2010]: 1-30. Reprinted by permission of The Catholic University of America Press. Part III: Interpretation 9. Philology and Presence Originally published as: “Philology and Presence.” The European Legacy: Toward New Paradigms 22.4 (2017): 456-471. Reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of International Society for the Study of European Ideas ©International Society for the Study of European Ideas’. 10. Our Father: Glossing a Bohemian Prayer Originally published as: “Our Father: Glossing a Bohemian Prayer.” Biblical Interpretation, 22 (2014): 71-89. Reprinted by permission of E.J. Brill – Leiden. 11. The God of Culture Originally published as: “The God of Culture.” East European Politics and Societies 16:2 (Spring, 2002): 572-588. Reprinted by permission of Sage Journals. 12. Jean Mabillon and the Sources of Medieval Ecclesiastical History (Part 1) Originally published as: “Jean Mabillon and the Sources of Medieval Ecclesiastical History: Part One »: American Benedictine Review 60:1 (March, 2009): 76-93. Reprinted by permission of The American Benedictine Academy. 13. Jean Mabillon and the Sources of Medieval Ecclesiastical History (Part 2) Originally published as: “Jean Mabillon and the Sources of Medieval Ecclesiastical History: Part Two »: American Benedictine Review 60:2 (June, 2009): 121-134. Reprinted by permission of The American Benedictine Academy Source link JUSTIFIABLE s’enrichit avec une nouvelle catégorie dédiée à l’Histoire du droit, alimentée par le flux RSS de univ-droit.fr. Cette section propose des articles approfondis et régulièrement mis à jour sur l’évolution des systèmes juridiques, les grandes doctrines, et les événements marquants qui ont façonné le droit contemporain. Ce nouvel espace est pensé pour les professionnels, les étudiants, et les passionnés d’histoire juridique, en quête de ressources fiables et structurées pour mieux comprendre les fondements et l’évolution des normes juridiques. Plongez dès maintenant dans cette catégorie pour explorer le passé et enrichir vos connaissances juridiques.

0 notes

Text

The Ideology of Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno, a philosopher of the 16th century, is known for his passionate defense of the idea of an infinite universe, a conception that led him to be accused of pantheism and eventually burned alive. He challenged the traditional view of a fixed and structured cosmos, proposing that the universe is a dynamic system in constant transformation, populated by an infinite number of stars and planets, many of which, according to him, could harbor intelligent life.

Bruno drew inspiration from the ideas of Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa, Copernicus, and Giovanni Battista della Porta. He is often cited as one of the first to suggest the infinitude of the universe. In his work On the Infinite Universe and Worlds (1584), he stated: "We declare this infinite space, since there is no reason, convenience, possibility, meaning, or nature that delineates a limit for it." For Bruno, this idea was not merely a theoretical speculation but a reflection of the nature of God: "The world is infinite because God is infinite. How can one believe that God, an infinite being, could have limited Himself by creating a closed and limited world?"

His view of relativity anticipated concepts that would be explored by Galileo, emphasizing that "in an infinite universe, any perspective of any object is always relative to the position of the observer," suggesting that there are "infinite possible references" and that none is privileged over the others.

Bruno was also a proponent of hylozoism, the belief that everything has life. He stated: "The Earth and the stars, as they provide life and sustenance to things, returning all matter they lend, are themselves endowed with life, in an even greater measure." This view led him to assert that "all forms of natural things have souls," reflecting his belief that "the spirit exists in all things," and that even the smallest particle contains a portion of spiritual substance.

In his work The Ash Wednesday Supper, Bruno challenged the idea that divinity should be sought outside ourselves, arguing that "we should not look for divinity outside ourselves, for it is by our side, or rather, in our innermost selves, more intimately in us than we are in ourselves." This statement underscores the deep connection he saw between humanity and the universe.

Bruno positioned himself against the religious orthodoxy of his time, confronting the Catholic Church and other institutions, which resulted in his excommunication. His book The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast is an example of his attack on organized religion and his pantheistic view of the world.

Thus, Giordano Bruno stands out as a bold thinker who, by proposing an infinite and interconnected universe, not only challenged established beliefs but also laid the groundwork for modern scientific inquiry, advocating a vision of the cosmos where life and divinity permeate all things. His philosophy continues to resonate, inviting us to explore the depth of the relationship between the human and the divine.

0 notes