#National Etruscan Museum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

National Etruscan Museum, Rome 21/07/23

#art#art history#academia#archaeology#anthropology#museum#roman art#etruscan art#ancient#national etruscan museum#sculpture#pottery

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bronze Statues and Coins Found at Ancient Sacred Bath in Tuscany

Archaeological excavations at the Bagno Grande sanctuary in San Casciano dei Bagni, Tuscany, Italy, have uncovered a wealth of artifacts that highlight the Etruscan-Roman heritage of this ancient thermal site.

Dating back to the 3rd century BCE, the sanctuary was originally constructed by the Etruscans and later developed by the Romans into the renowned spa complex, Balnea Clusinae. Revered for its therapeutic hot springs, the site attracted visitors from across the Roman Empire, including Caesar Augustus.

The recent excavation, spanning June to October 2024, focused on the sacred temenos, a walled enclosure surrounding the sanctuary, and revealed the remnants of a central temple built around a thermal water basin. Within this sacred space, archaeologists unearthed an array of votive offerings and artifacts remarkably preserved by thermal waters and clay.

Among the most notable finds are four bronze statues, votive limbs, and heads, inscribed with dedications. A striking bronze torso, bisected from neck to genitals, was dedicated by a man named Gaius Roscius to the “Hot Spring.” Researchers suggest this statue symbolizes the healing of specific ailments. Other discoveries include a child statue portraying an augur priest holding a pentagonal ball, likely used in divination rituals, and elegant votive heads inscribed in Latin.

Inscriptions in both Etruscan and Latin were uncovered, including dedications to the Nymphs and the thermal spring, referred to as “Flere Havens” in Etruscan, and oaths to Fortuna and the Genius of the Emperor.

The sacred basin contained a diverse range of offerings, including oil lamps, glass unguent jars, painted terracotta anatomical votives, and coins—more than 10,000 spanning the Roman Republic to the Empire. Precious metals, such as a gold crown and ring, Roman aurei, and fragments of amber and gemstones, were also uncovered. Notably, the presence of preserved eggs, some with intact yolks, suggests rites symbolizing rebirth and regeneration.

Decorative elements such as pinecones, branches, and bronze serpents—one nearly a meter long and thought to represent the Agathodaimon, a protective spirit—emphasize the connection between the rejuvenating waters and nature’s generative power.

Efforts are underway to preserve these extraordinary finds. The National Archaeological Museum of San Casciano dei Bagni is being established in the Archpriest’s Palace to house the artifacts, while a thermal archaeological park is planned around Bagno Grande to promote cultural tourism.

By Dario Radley.

#Bronze Statues and Coins Found at Ancient Sacred Bath in Tuscany#Bagno Grande sanctuary in San Casciano dei Bagni#Balnea Clusinae#roman coins#ancient coins#bronze#bronze statues#bronze sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman era

580 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etruscan art from the temple dedicated to the goddess Uni in Pyrgi dated ca 500 BC. National Etruscan Museum in Rome, Italy.

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Most EPIC Off-the-Beaten-Path Ancient Sculptures in Rome You Need to Discover

The Boxer, 1st century AD, Altemps Palace.

Sarcophagus of the Spouses, 530–510 BCE, National Etruscan Museum.

Portonaccio sarcophagus, late 2nd century AD, Palazzo Massimo.

Corsini Throne, 1st century AD, Corsini Gallery.

By: Learn Latin

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

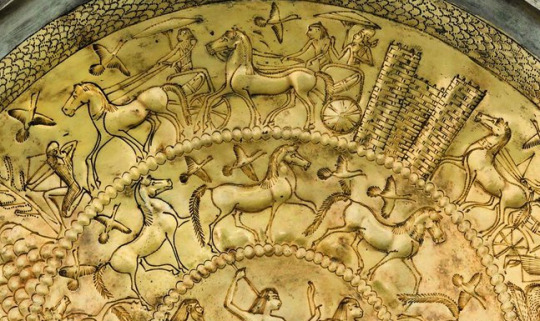

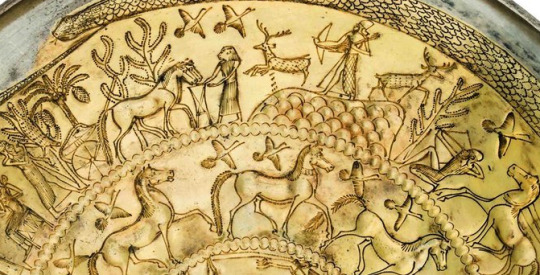

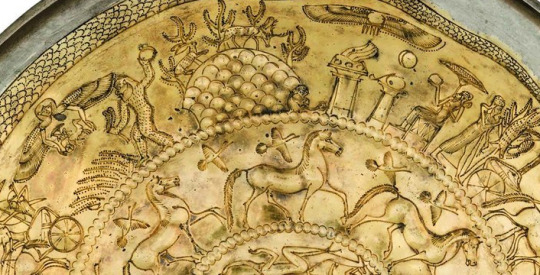

Phoenician Bowl with encircling Serpent Bernardini Tomb (Palestrina, Italy) c. 700 BCE The National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia Rome, Italy

#cyprus#rome#italy#egypt#egyptian gods#canaan#canaanite gods#phoenicia#phoenician gods#aram#aramean gods#syria#syrian gods#levantine gods#mesopotamia#mesopotamian gods#pagan gods#polytheism#archeology#magic#witchcraft#witchblr#paganblr#occult#uroboros#ouroboros#warfare#hunting#soldiers#birds

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Etruscan head of a youth from Veii 430-420 BCE. National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia.

746 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold swivel ring with carnelian intaglio depicting a warrior, Etruscan, 4th-3rd century BC

from The National Museums, Liverpool

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivy Nicholson, National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia, Photo by Pasquale De Antonis, 1956

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

Winged Horses of Tarquinia - Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy.

490-480 BC

The high relief sculpture is of a pair of winged horses positioned side by side standing in profile, prancing and harnessed to a biga. They once decorated the most important temple of the ancient Etruscan city of Tarquinia, the Temple of the Queen Ara (Temple of Ara della Regina). The horses were sculpted on a 114 cm high and 124 cm wide terracotta panel. They are a masterpiece of Tarquinian coroplastic art, and now considered to be the symbol of the town. The Winged Horses was found shattered into more than 100 shards when archaeologist Pietro Romanelli excavated the temple in 1938. They have been painstaking restored to its original condition. (National Archaeological Museum of Tarquinia)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques-Albert Senave - Copyist in a gallery of the Louvre -

oil on panel, height: 28.5 cm (11.2 in); width: 36.2 cm (14.2 in)

Louvre Museum

The Louvre or the Louvre Museum is a national art museum in Paris, France. It is located on the Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement (district or ward) and home to some of the most canonical works of Western art, including the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo. The museum is housed in the Louvre Palace, originally built in the late 12th to 13th century under Philip II. Remnants of the Medieval Louvre fortress are visible in the basement of the museum. Due to urban expansion, the fortress eventually lost its defensive function, and in 1546 Francis I converted it into the primary residence of the French kings.

The building was extended many times to form the present Louvre Palace. In 1682, Louis XIV chose the Palace of Versailles for his household, leaving the Louvre primarily as a place to display the royal collection, including, from 1692, a collection of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. In 1692, the building was occupied by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres and the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which in 1699 held the first of a series of salons. The Académie remained at the Louvre for 100 years. During the French Revolution, the National Assembly decreed that the Louvre should be used as a museum to display the nation's masterpieces.

The museum opened on 10 August 1793 with an exhibition of 537 paintings, the majority of the works being royal and confiscated church property. Because of structural problems with the building, the museum was closed from 1796 until 1801. The collection was increased under Napoleon and the museum was renamed Musée Napoléon, but after Napoleon's abdication, many works seized by his armies were returned to their original owners. The collection was further increased during the reigns of Louis XVIII and Charles X, and during the Second French Empire the museum gained 20,000 pieces. Holdings have grown steadily through donations and bequests since the Third Republic. The collection is divided among eight curatorial departments: Egyptian Antiquities; Near Eastern Antiquities; Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities; Islamic Art; Sculpture; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints and Drawings.

The Musée du Louvre contains approximately 500,000 objects and displays 35,000 works of art in eight curatorial departments with more than 60,600 m2 (652,000 sq ft) dedicated to the permanent collection. The Louvre exhibits sculptures, objets d'art, paintings, drawings, and archaeological finds. At any given point in time, approximately 38,000 objects from prehistory to the 21st century are being exhibited over an area of 72,735 m2 (782,910 sq ft), making it the largest museum in the world. It received 8.9 million visitors in 2023, 14 percent more than in 2022, but still below the 10.1 million visitors in 2018, making it the most-visited museum in the world.

Jacques-Albert Senave (1758–1823) was a Flemish painter mainly active in Paris during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He is known for his genre scenes, history paintings, landscapes, city views, market scenes and portraits.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legendary Creatures: Harpy

By Written and illustrated by John Vinycomb (1833–1928 biography) - Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art http://heraldicart.org/fictitious-and-symbolic-creatures-in-art/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114035415

Harpies (Greek: ἅρπυια hárpyia Latin: harpȳia) are Greek and Roman creatures that are half-human (chest and heads) and half-birds (wings, legs, tail) and personify storm winds. They are mostly found in Homeric poems.

Source https://www.flickr.com/photos/duncanh1/4565921045

The human half of the harpy is a young woman who looks pale with hunger according to the Greeks and in pottery. The Romans considered them to be ugly. Ovid, who lived from 43 BCE to 17 or 18 CE, described them as a blend of humans and vultures. Hesiod described them as fair haired and winged maidens and able to fly as fast as the wind. Aeschylus, who lived from about 525 to 456 BCE, described them as ugly and seems to have influenced those who came after.

Boreads chasing Harpies, Laconian black-figure kylix C6th B.C., National Etruscan Museum

Harpies began as personifications of winds, especially those that are destructive. The word 'harpy' means 'snatcher' or 'swift robbers' so they are said to steal food and evildoers, taking the evildoers to the Eumenides, underworld goddesses of vengeance. They were also called 'the hounds of mighty Zeus', relating them to Zeus' thunder. They were also called guardians of the underworld, keeping out other creatures like the Chimera, Gorgons, and Centaurs.

The exact relationships and names of the harpies vary by writer. Hesiod stated that their parents were Thaumas, a sea god who was the son of Gaia and Pontus, a primordial sea god, and Electra, an Oceanid, an ocean nymph who is a daughter of the Titan Oceanus and Tethys, a Titan, and sisters to the river god Hydaspes. Hesiod lists their names as Aello, meaning 'storm swift', and Ocypete, meaning 'the swift wing'.

Museum Collection The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu Catalogue No. Malibu 85.AE.316 Beazley Archive No. 30369 Ware Attic Red Figure Shape Hydria, Kalpis Painter Attributed to the the Kleophrades Painter Date ca 480 B.C. Period Late Archaic

The most popular story involving harpies is when King Phineus of Thrace angered Zeus by using his gift of prophecy to reveal the plans of the gods, so Zeus blinded him and put him on an island with a banquet that the harpies at before he could eat any of it. This continued until Jason and the Argonauts arrived. Phineus bargained for his delivery from the harpies by using his gift of prophecy to guide them. The Boreads, sons of the North Wind, Boreas, drove off the harpies. There was a prophecy that the Boreads would destroy the harpies, but that the Boreads would die if they didn't defeat the harpies. The harpies fled and one fell into the Tigris, and the other reached the Echinades, a group of islands in the Ionian Sea, and collapsed with fatigue, along with the Boread that chased her. She promised to leave Phineus alone going forward and they were both allowed to live. Aeneas is then said to meet them during the Trojan war where they took away Trojans.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

My interpretation of this etruscan bronze mirror from florence (in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence) in which Hercle becomes Uni's son through adoption (breastfeeding)

I think sometimes I just have to leave things as they end up. Is this where i wanted to leave it? absolutely not, but i have to stop at some point. maybe i'll come back to it one day.

At least i learned a lot about the Etruscans :)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Golden Orphism Book, the oldest book in the world.

El Libro del Orfismo de Oro, el libro más antiguo del mundo.

(English / Español / Italiano)

Perhaps the oldest multi-page book in the world, dating from around 660 BC, it was discovered in the Strouma River in Bulgaria. The book is made of six sheets of twenty-four carat gold, each 5x4.5 cm, held together by rings. The Book of Golden Orphism, created over 2500 years ago, contains illustrations of a horse, a mermaid, a harp, soldiers, and text in the Etruscan language. The book was anonymously donated to the National Museum of History in Sofia, where it is currently housed. The authenticity of the book has been confirmed by two experts in Sofia and London, according to the museum's director. The Etruscans were a people originating from Lydia, in what is now Turkey, settling in central Italy about three thousand years ago. Thracian Orphism combined the cult of the Earth and the cult of the Sun, personified by Orpheus and Zalmoxis.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Quizás es el libro de varias páginas más antiguo del mundo, datado hacia el 660 a.C, fue descubierto en el río Strouma, en Bulgaria. El libro está hecho de seis láminas de oro de veinticuatro quilates, de 5 x 4,5 cm cada una, unidas por dos anillos. El Libro del Orfismo de Oro, creado hace más de 2500 años, contiene ilustraciones de un caballo, una sirena, un arpa, soldados, y texto en lengua etrusca. El libro fue donado anónimamente al Museo Nacional de Historia de Sofia, donde se encuentra actualmente. La autenticidad del libro ha sido confirmada por dos expertos en Sofía y Londres, según el director del museo. Los etruscos fueron un pueblo originario de Lidia, en lo que es actualmente Turquía, asentándose en la Italia central hace tres mil años aproximadamente. El orfismo tracio combinaba el culto a la Tierra y el culto al Sol, personificado por Orfeo y Zalmoxis.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Forse il più antico libro a più pagine del mondo, risalente al 660 a.C. circa, è stato rinvenuto nel fiume Strouma in Bulgaria. Il libro è composto da sei fogli d'oro a ventiquattro carati, de 5 x 4,5 cm ciascuno, tenuti insieme da due anelli.

Il Libro dell'Orfismo d'Oro, creato oltre 2500 anni fa, contiene illustrazioni di un cavallo, una sirena, un'arpa, soldati e testi in lingua etrusca. Il libro è stato donato anonimamente al Museo Nazionale di Storia di Sofia, dove è attualmente conservato.

L'autenticità del libro è stata confermata da due esperti a Sofia e a Londra, secondo il direttore del museo. Gli Etruschi erano un popolo originario della Lidia, nell'attuale Turchia, che si stabilì nell'Italia centrale circa tremila anni fa. L'orfismo tracio combinava il culto della Terra e quello del Sole, personificato da Orfeo e Zalmoxis.

Source: Indika Ki Som. Arqueologia, Historia y Arte

#ancient history#historia antigua#etruscos#etruscans#etruschi#7th century bc#660 bc#s.VII a.C.#The Book of Golden Orphism#Libro dell'Orfismo d'Oro

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etruscan Amphora; 6th Century BC. National Roman Museum, Italy

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

And so, today is Mother's Day Perhaps I should be particularly struck by this anniversary, given that my work has a lot to do with motherhood: but in reality the idea of beatifying and respecting women only when they are mothers has always irritated me deeply: in fact I I have always preferred to focus on aspects of my profession that allow women to freely experience their sexuality and reproductive choices. I was born and raised in a country where the greatest representation of women is Holy Mary, the prototype of the one who has never been able to choose anything about her life. And if 2000 years ago it was a situation common to many women, I really hoped that in 2024, thanks also to medical advances that allow safe and available Contraception and Termination of Pregnancy, it was just the distant memory of a chauvinist and patriarchal world. Instead, unfortunately, I was able to see first-hand how this is still the daily reality of many women in the world, never in control of their own bodies and their own lives. And so, this morning, I wished my mother -who is still amazed to see me at home after all these months - for the Happy Day. And I won't publish even one of my photos of mothers I've assisted, I really wouldn't know which one to choose, each of them is a precious bitch that I will remember fondly and keep for myself. But there is a statue, which I saw as a very young student, which struck me for its calm naturalness and which I have always associated with motherhood: a woman from almost 3000 years ago, perhaps an ancestor of mine (very unlikely, but I have always felt a strong bond with the Etruscans), certainly not a virgin mother (let's leave those to Middle Eastern legends), just a young woman with her child, who continues to speak to me from the depths of time. Happy Mother's Day. One of the main masterpieces of Etruscan art preserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence is a mother breastfeeding a child: she is the Mater Matuta, the Italian goddess of the morning and the dawn, and consequently protector of fertility, motherhood and birth. She was found in a necropolis near Chianciano Terme. The work strikes the observer with its monumentality which however does not affect the degree of realism that the sculptor managed to give it (observe the naturalness of the movement of the hands holding the child, but also the folds of the drapery). In ancient times, the cult of the mother goddess was deeply rooted in Italian territory, this also explains why some depictions of mothers with their children have reached us in Etruscan sculpture. The votive statues could also represent newborns, and had the aim of obtaining protection from the divinities for the little ones.

#Mother's Day#Mater Matuta#Women's fundamental rights#Holy Mother#Archaeological Museum of Florence#Etruscan art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Origins of Boxing

Historical Trace of Boxing's Origins

The origins of boxing, tracing its roots from ancient Greece and Rome to the bare-knuckle era in 18th-century England, reveal a fascinating evolution of a combat sport that has captivated civilizations for millennia. This survey note provides a comprehensive exploration, expanding on the key points with detailed historical context, supported by various sources.

Ancient Greek Boxing: The Foundation

Boxing, known as pygmachia in ancient Greece, dates back to at least the 8th century BC, with mentions in Homer's Iliad. It became an official Olympic event in 688 BC, marking its significance in Greek athletic culture. Fighters used leather thongs, called himantes, wrapped around their hands for protection, with no weight categories and no rounds. Fights continued until one fighter acknowledged defeat by raising an index finger or was incapacitated, often resulting in severe injuries. The stance typically involved an advanced left leg, with the left arm semi-extended for guarding and jabbing, and the right arm drawn back for powerful strikes, primarily targeting the head. Archaeological evidence, such as a boxing scene on a Panathenaic amphora (c. 336 BC) housed at the British Museum (Ancient Greece, Boxers (youths), Panathenaic Amphora), and frescoes from Akrotiri (c. 1650 BC) (Young boxers fresco, Akrotiri, Greece), confirms its early practice. Legends, like Theseus inventing a form where fighters sat and beat each other until death, highlight its brutal nature, though later standing fights became standard.

Ancient Roman Boxing: A Violent Spectacle

In ancient Rome, boxing, termed pugilatus (from pugnus, "fist"), was influenced by Greek practices via the Etruscans, becoming a popular spectator sport. Fighters used caestus, gloves reinforced with metal studs or spikes, significantly increasing the sport's lethality. Evidence from literature, sculptures, wall paintings, and mosaics, such as a Roman mosaic of a boxer and rooster (first century AD) at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples (Naples Museum 18 (14972772469).jpg), shows its integration into gladiatorial spectacles. Fights, often to the death, lacked weight classes and time limits, with no rules against hitting fallen opponents, reflecting a more brutal approach than Greek boxing. This violence led to its ban around 400 CE by Emperor Theodosius I, aligning with the decline of pagan games under Christian influence.

The Middle Ages: A Period of Silence

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, boxing entered a period of obscurity during the Middle Ages. Historical records suggest minimal practice, with the sport overshadowed by weapon-based combat and the church's growing influence discouraging violent activities. Changing views on public entertainment and moral values contributed to its decline, with arenas for boxing matches becoming empty. This gap, lasting roughly from the 5th to the 17th century, marks a significant interruption in the sport's continuity, with no notable documentation in Mediterranean or European contexts.

Revival in 17th and 18th Century England: The Bare-Knuckle Era

Boxing re-emerged in England in the late 17th century as bare-knuckle prizefighting, initially illegal but gaining popularity, especially in London. The first documented bout was in 1681, arranged by Christopher Monck, Second Duke of Albemarle, between his butler and butcher, with regular contests by 1698 at the Royal Theatre. Fighters competed without gloves, for purses and side bets, with no weight divisions, often continuing until one could not proceed. This era saw the rise of notable figures, starting with James Figg, acclaimed champion of England in 1719, holding the title for 15 years with nearly 300 fights, all victories, employing fencing-inspired footwork. His pupil, Jack Broughton, became champion from 1734-1750 and, after a fatal fight in 1741, introduced the first rules in 1743, banning hits on downed opponents and hair-pulling, aiming to make boxing respectable. These rules governed until 1838, replaced by the London Prize Ring Rules, and later the Revised London Prize Ring Rules in 1853.

Other notable boxers include George Taylor, the first to tour in boxing booths by 1735, Tom Johnson (champion 1784-1791), Daniel Mendoza (champion 1792-1795, known for scientific boxing), and John Jackson (champion 1795-1803). The sport, while brutal, laid the groundwork for modern boxing, with fights often held in circles, influencing the term "boxing ring."

Cultural and Historical Connections

While there's no direct evidence that 18th-century English boxers looked to ancient Greek and Roman boxing for inspiration, the revival likely drew on historical knowledge of these practices, reflecting the Age of Enlightenment's fascination with classical antiquity. The similarities, such as no weight classes and fights to submission, suggest an unconscious echo, though the English form evolved independently, focusing on prize fighting and betting, distinct from ancient rituals.

Conclusion

The journey of boxing from ancient Greece and Rome to 18th-century England highlights its resilience and adaptability. From Olympic glory to Roman brutality, a medieval silence, and a vibrant revival, the sport's evolution reflects societal shifts, with bare-knuckle prizefighting in England marking a pivotal chapter, driven by figures like Figg and Broughton, setting the stage for modern boxing.

Sources:

Boxing - Wikipedia, comprehensive history

Ancient Greek boxing - Detailed origins

Boxing in the Ancient Olympic Games - Olympic perspective

Boxing - Bare Knuckle, Rules, History - Britannica

History of Boxing - Detailed timeline

Boxing in the Roman Empire - World History Encyclopedia

Ancient Greek boxing - Mobile version

Naples Museum 18 (14972772469).jpg - Roman boxing evidence

Young boxers fresco, Akrotiri, Greece - Early evidence

Ancient Greece, Boxers (youths), Panathenaic Amphora - Greek artifact

0 notes