#Nat Struct Mol Biol

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Molecular analysis of PRC2 recruitment to DNA in chromatin and its inhibition by #RNA.

Related Articles Molecular analysis of PRC2 recruitment to DNA in chromatin and its inhibition by #RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017 Dec;24(12):1028-1038 Authors: Wang X, Paucek RD, Gooding AR, Brown ZZ, Ge EJ, Muir TW, Cech TR Abstract Many studies have revealed pathways of epigenetic gene silencing by Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) in vivo, but understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms requires biochemistry. Here we analyze interactions of reconstituted human PRC2 with nucleosome complexes. Histone modifications, the H3K27M #cancer mutation, and inclusion of JARID2 or EZH1 in the PRC2 complex have unexpectedly minor effects on PRC2-nucleosome binding. Instead, protein-free linker DNA dominates the PRC2-nucleosome interaction. Specificity for CG-rich sequences is consistent with PRC2 occupying CG-rich DNA in vivo. PRC2 preferentially binds methylated DNA regulated by its AEBP2 subunit, suggesting how DNA and histone methylation collaborate to repress chromatin. We find that #RNA, known to inhibit PRC2 activity, is not a methyltransferase inhibitor per se. Instead, #RNA sequesters PRC2 from nucleosome substrates, because PRC2 binding requires linker DNA, and #RNA and DNA binding are mutually exclusive. Together, we provide a model for PRC2 recruitment and an explanation for how actively transcribed genomic regions bind PRC2 but escape silencing. PMID: 29058709 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] http://bit.ly/2CqTMlx #Pubmed

1 note

·

View note

Text

Predatory Snail (Conus)

*hehe will post our next blogpost on the account*

Group 3

I. Classification

Kingdom Animalia Subkingdom Bilateria Infrakingdom Protosomia Superphylum Lophozoa Phylum Mollusca Class Gastropoda Subclass Prosobranchia Order Neogastropoda Family Conidae Genus Conus

ITIS (n.d.)

II. Biology

Tropical Dwellers

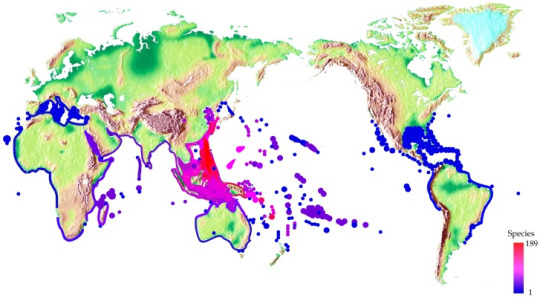

Approximately, there are 700 Conus species. The majority is found throughout tropical and subtropical waters, such as the South China Sea, Australia, and the Pacific Ocean. Few species were found in South Africa, Southern Australia, Southern Japan, and Mediterranean Sea (Dutertre and Lewis, 2011). There are also existing species thriving in temperate waters such as C. californicus which are found in the North American Pacific coast(Gao et al. 2017).

Figure 1. Worldwide distribution of cone snails. Spot colors stand for various species number (Gao et al. 2017). Image retrieved from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5744117/#B37-toxins-09-00397

Habitat

Cone snails are commonly found in intertidal and shallow sublittoral zones. They are present in coral reef areas, sand bottoms, and silty crevices. Some were reportedly found in mangrove areas, and in deeper waters of up to 400-600 meters (Carpenter and Niem, 1998; Dutertre and Lewis, 2011).

Anatomy

Cone snails are gastropods. Gastropods have asymmetrical body symmetry and their shells are spirally coiled. Conus shells are cone-shaped. The spire of the shell is conical and moderately low to flat. It has a well-developed body whorl that tapers towards the narrow anterior end. The aperture is very long and narrow. There is a notch at the aperture’s posterior end, and a short, wide siphonal canal is located at the anterior end. The operculum is corneous, small, and ovate to claw-shaped. However, the operculum may not always be present (Carpenter and Angelis, 2016).

Figure 2. Ventral view of Conus shell with labelled parts.

Image retrieved from:http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5712e.pdf

The soft body of gastropods has 4 main regions: the head, the foot, the visceral mass, and the mantle. The head protrudes from the anterior end. The foot is a muscular ventral organ with a flattened base used for locomotion (creeping or burrowing). The visceral mass is located in the spire of the shell and contains most organ systems. The mantle is a collar-like tegument which lines and secretes the shell and forms a mantle cavity normally provided with respiratory gills in aquatic species (Carpenter and Angelis, 2016).

Figure 3. Internal anatomy of Conus striatus.

Image retrieved from:https://www.marinelifephotography.com/marine/mollusks/gastropods/cones/cones.htm

Cone snails have a specialized venom apparatus that comprises a venom gland, salivary glands, a radular sac, a pharynx, a proboscis, and a radula. The radula of the cone snail is hollowed and barbed and it resembles a harpoon. These harpoons are produced and stored in the radular sac, which is divided into two arms and connects to the pharynx. The short arm contains a few fully formed radula while the long arm is where the radulas are produced.

The cone snail uses chemosensory to detect prey. Once the prey is detected, it will extend its proboscis and shoot its radula which will inject a potent venom to paralyze its prey (Kohn et al. 1972; Marsh 1977; Salisbury et al. 2010; Schulz et al. 2004).

Images retrieved from:https://kristinabarclay.wordpress.com/2016/07/

Figure 4. Close-up photo of a cone snail’s radula (top). Cone snail radula under an electron microscope (bottom).

Life Cycle

Most cone snail species have separate sexes and fertilization happens internally. Cone snails lay their eggs once a year. The egg masses of cone snails are usually made up of up to 25 egg capsules with each capsule containing roughly around 1000 eggs (Zehra & Perveen 1991). Two types of cone snail hatchlings have been described, the veliger stage (free-swimming larvae) and veliconcha stage (juvenile snails). During these stages, only a few will survive. In between 1 and 50 days, the snails will undergo the pelagic stage (Perron, 1983).

According to Rockel et al as cited in Dutertre and Lewis (2011), it is estimated that cone snails have a lifespan of 10-20 years. This estimated lifespan is based on the marks and shell growth of the snail. They can reach a maximum size of > 20 cm, but most species are < 8 cm and weight < 100 g.

Figure 5. Conus magus with egg sacs

Image retrieved from:https://poppe-images.com/?t=17&photoid=951805

Figure 6. Conus ammiralis with its egg capsules attached to Halimeda sp. algae.

Images retrieved from:http://www.underwaterkwaj.com/shell/cone/Conus-ammiralis.htm

III. Relationship with Humans

Cone snails are exploited for ornamental trade and research.

Conus shells have economic value and are marketed as ornaments. One of the rarest and most valuable shells in the world is the Conus gloriamaris or the Glory of the Seas Cone (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2020).

Conantokins or sleeper peptides from the geographic cone snail are short chain peptides that can affect neural receptors in fish and mammals. This peptide has great potential that humans can benefit from when it comes to paint ecpetop, drug and alcohol withdrawal symptoms and learning. Con-G one of the conatokins from the geographic cone snail has been found to act as a neuroprotective agent in brain ischemia from strokes. Conus shells contain conotoxin which is used for drug development. For example, the ω-MVIIA (ziconotide) is a well-known conotoxin approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2004) to treat chronic pain in cancer and AIDS patients. It is derived from the toxin/venom produced by Conus Magus (Gao et al. 2017). Conus regius is rich in alpha-conotoxins, which can target nicotine receptors and can help in research concerning the development of medicine for Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, lung cancer and even tobacco addiction. (Kompella et al. 2015)

Death by conus?

Humans can be negatively affected by conus. It is recorded that 30 humans have died from a conus sting. Once stung, the victim feels numbness accompanied by dizziness, slurred speech and respiratory paralysis and then death.

IV. Did you know?

1. The venom from one cone snail has a hypothesized potential of killing up to 700 people. (Kapil S., et al.)

2. The Geographic Cone Snail (Conus geographus), according to BBC Earth, is the most toxic cone snail in the world. Its venom contains a protein which when isolated scientists can be used as effectively as a morphine substitute without the harmful side effects.

3. A person was recorded to be killed from a cone snail sting in as short as 5 minutes!

4. Some cone snails are solitary in nature, like the Conus spurius or the Alphabet cone, and the only time individuals have contact with each other is during mating!

5. The largest Alphabet cone shell was recorded at 80 mm or as large as your regular sized mountain dew can!

6. Conus species were observed to exhibit “fishermen-like” behavior when hunting for food! They use their proboscis as lures and catch their prey, scientists even coined the term hook and line method to describe this hunting behavior, just like the fishing method.

7. The cone snail is the only recorded species in the animal kingdom to use insulin as a chemical weapon, a hormone that is also used to help diabetic people! Even though this is used as a means to catch prey, scientists actually used insulin from the cone snail’s venom and combined it with human insulin creating a new type of insulin called mini-Ins.

IV. References

Chivian, E., et. al. (2003, November). The Threat to Cone Snails. Retrieved October 3, 2020 from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/9046809_The_Threat_to_Cone_Snails_1

Gao B, Peng C, Yang J, Yi Y, Zhang J & Shi Q. 2017. Cone Snails: A Big Store of Conotoxins for Novel Drug Discovery. 2017; 9(12): 397. DOI: 10.3390/toxins9120397

Geography Cone. (2018, September 21). Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/g/geography-cone/

Hall, M. (n.d.). Conus geographus (geography cone snail). Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Conus_geographus/

Kane, S. (2017, December 4). The most venomous animal on Earth is truly surprising. Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://www.businessinsider.com/most-venemous-animal-cone-snail-2016-2?international=true&r=US&IR=T

Kohn, A.J. (2016). Human injuries and fatalities due to venomous marine snails of the family Conidae. DOI: 10.5414/CP202630

Kompella SN, Hung A, Clark RJ, Mari F, Adams DJ. 2015. Alanine Scan of α-Conotoxin RegIIA Reveals a Selective α3β4 Nicotine Acetylcholine Receptore Antagoist. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2015; 290(2): 1039 DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605592

Kohn, A.J. (2016). Human injuries and fatalities due to venomous marine snails of the family Conidae. DOI: 10.5414/CP202630

Safavi-Hemami, J., et. al. (2014). Specialized insulin is used for chemical warfare by fish-hunting cone snails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.1423857112 (2015).

Sygo, M. (1999). "Conus spurius" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved October 03, 2020 from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Conus_spurius/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2020. Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/animal/cone-shell

Xiong, X., Menting, J.G., Disotuar, M.M. et al.(2020). A structurally minimized yet fully active insulin based on cone-snail venom insulin principles. Nat Struct Mol Biol 27, 615–624 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-020-0430-8

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

"ZNF-451 E3 SUMO Ligase, as Putative Partner for MAPKK-RNF4 Signaling Complex", A Hypothesis and Project by Alex Sobko, PhD from Alexander Sobko on Vimeo.

ZNF-451 E3 SUMO Ligase, as Putative Partner for MAPKK-RNF4 Signaling Complex - A Hypothesis and New Project” by Dr. Alex Sobko, PhD

Copyright:

© 2022, Alex Sobko, PhD © 2022, Record, edit, design, posts at social media by Alex Sobko, PhD, 8762728, South-West IL (ישראל).

References:

Sobko A. A hypothetical MEK1-MIP1-SMEK multiprotein signaling complex may function in Dictyostelium and mammalian cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2020;64(10-11-12):495-498.

Sobko A, Ma H, Firtel RA. Regulated SUMOylation and ubiquitination of DdMEK1 is required for proper chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2002 Jun;2(6):745-56.

Eisenhardt N.…Pichler A. A new vertebrate SUMO enzyme family reveals insights into SUMO-chain assembly. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015 Dec;22(12):959-67.

Koidl S.…Pichler A. The SUMO2/3 specific E3 ligase ZNF451-1 regulates PML stability. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016 Oct; 79:478-487.

Cuijpers SAG, Willemstein E, Vertegaal ACO. Converging Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) and Ubiquitin Signaling: Improved Methodology Identifies Co-modified Target Proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017 Dec;16(12):2281-2295.

Bigenzahn JW…Superti-Furga G. LZTR1 is a regulator of RAS ubiquitination and signaling. Science. 2018 Dec 7;362(6419):1171-1177.

Steklov M…Sablina AA. Mutations in LZTR1 drive human disease by dysregulating RAS ubiquitination. Science. 2018 Dec 7;362(6419):1177-1182.

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/metabolic-control-of-brisc-shmt2-assembly-regulates-immune-signalling/

Metabolic control of BRISC–SHMT2 assembly regulates immune signalling

1.

Giardina, G. et al. How pyridoxal 5′-phosphate differentially regulates human cytosolic and mitochondrial serine hydroxymethyltransferase oligomeric state. FEBS J. 282, 1225–1241 (2015).

2.

Anderson, D. D., Woeller, C. F., Chiang, E.-P., Shane, B. & Stover, P. J. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase anchors de novo thymidylate synthesis pathway to nuclear lamina for DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7051–7062 (2012).

3.

Szebenyi, D. M., Liu, X., Kriksunov, I. A., Stover, P. J. & Thiel, D. J. Structure of a murine cytoplasmic serine hydroxymethyltransferase quinonoid ternary complex: evidence for asymmetric obligate dimers. Biochemistry 39, 13313–13323 (2000).

4.

Patterson-Fortin, J., Shao, G., Bretscher, H., Messick, T. E. & Greenberg, R. A. Differential regulation of JAMM domain deubiquitinating enzyme activity within the RAP80 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30971–30981 (2010).

5.

Cooper, E. M., Boeke, J. D. & Cohen, R. E. Specificity of the BRISC deubiquitinating enzyme is not due to selective binding to Lys63-linked polyubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10344–10352 (2010).

6.

Feng, L., Wang, J. & Chen, J. The Lys63-specific deubiquitinating enzyme BRCC36 is regulated by two scaffold proteins localizing in different subcellular compartments. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30982–30988 (2010).

7.

Sobhian, B. et al. RAP80 targets BRCA1 to specific ubiquitin structures at DNA damage sites. Science 316, 1198–1202 (2007).

8.

Wang, B. et al. Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science 316, 1194–1198 (2007).

9.

Kim, H., Chen, J. & Yu, X. Ubiquitin-binding protein RAP80 mediates BRCA1-dependent DNA damage response. Science 316, 1202–1205 (2007).

10.

Jiang, Q. et al. MERIT40 cooperates with BRCA2 to resolve DNA interstrand cross-links. Genes Dev. 29, 1955–1968 (2015).

11.

Sowa, M. E., Bennett, E. J., Gygi, S. P. & Harper, J. W. Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell 138, 389–403 (2009).

12.

Zheng, H. et al. A BRISC-SHMT complex deubiquitinates IFNAR1 and regulates interferon responses. Cell Reports 5, 180–193 (2013).

13.

Zeqiraj, E. et al. Higher-order assembly of BRCC36–KIAA0157 is required for DUB activity and biological function. Mol. Cell 59, 970–983 (2015).

14.

Walden, M., Masandi, S. K., Pawłowski, K. & Zeqiraj, E. Pseudo-DUBs as allosteric activators and molecular scaffolds of protein complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 46, 453–466 (2018).

15.

Kyrieleis, O. J. P. et al. Three-dimensional architecture of the human BRCA1-A histone deubiquitinase core complex. Cell Reports 17, 3099–3106 (2016).

16.

Zanetti, K. A. & Stover, P. J. Pyridoxal phosphate inhibits dynamic subunit interchange among serine hydroxymethyltransferase tetramers. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10142–10149 (2003).

17.

Jagath, J. R., Sharma, B., Rao, N. A. & Savithri, H. S. The role of His-134, -147, and -150 residues in subunit assembly, cofactor binding, and catalysis of sheep liver cytosolic serine hydroxymethyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24355–24362 (1997).

18.

Jala, V. R., Appaji Rao, N. & Savithri, H. S. Identification of amino acid residues, essential for maintaining the tetrameric structure of sheep liver cytosolic serine hydroxymethyltransferase, by targeted mutagenesis. Biochem. J. 369, 469–476 (2003).

19.

Krishna Rao, J. V., Jagath, J. R., Sharma, B., Appaji Rao, N. & Savithri, H. S. Asp-89: a critical residue in maintaining the oligomeric structure of sheep liver cytosolic serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Biochem. J. 343, 257–263 (1999).

20.

Xu, D., Jaroszewski, L., Li, Z. & Godzik, A. FFAS-3D: improving fold recognition by including optimized structural features and template re-ranking. Bioinformatics 30, 660–667 (2014).

21.

Zimmermann, L. et al. A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new HHpred server at its core. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2237–2243 (2018).

22.

Björklund, A. K., Ekman, D. & Elofsson, A. Expansion of protein domain repeats. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2, e114 (2006).

23.

Hu, X. et al. NBA1/MERIT40 and BRE interaction is required for the integrity of two distinct deubiquitinating enzyme BRCC36-containing complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11734–11745 (2011).

24.

Guettler, S. et al. Structural basis and sequence rules for substrate recognition by tankyrase explain the basis for cherubism disease. Cell 147, 1340–1354 (2011).

25.

Hamilton, G., Colbert, J. D., Schuettelkopf, A. W. & Watts, C. Cystatin F is a cathepsin C-directed protease inhibitor regulated by proteolysis. EMBO J. 27, 499–508 (2008).

26.

Zheng, N. & Shabek, N. Ubiquitin ligases: structure, function, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 129–157 (2017).

27.

Yang, X. et al. SHMT2 desuccinylation by SIRT5 drives cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 78, 372–386 (2018).

28.

Cao, J. et al. HDAC11 regulates type I interferon signaling through defatty-acylation of SHMT2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5487–5492 (2019).

29.

Fitzgerald, D. J., et al. Protein complex expression by using multigene baculoviral vectors. Nat. Methods 3, 1021–1032 (2006).

30.

Thompson, R. F., Iadanza, M. G., Hesketh, E. L., Rawson, S. & Ranson, N. A. Collection, pre-processing and on-the-fly analysis of data for high-resolution, single-particle cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Protocols 14, 100–118 (2019).

31.

Zivanov, J. et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7, e42166 (2018).

32.

Zheng, S. Q., et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 2006 3:12 14, 331–332 (2017).

33.

Zhang, K. Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016).

34.

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protocols 10, 845–858 (2015).

35.

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

36.

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 (2010).

37.

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 213–221 (2010).

38.

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 12–21 (2010).

39.

Pickart, C. M. & Raasi, S. Controlled synthesis of polyubiquitin chains Methods Enzymol. 399, 21–36 (2005).

40.

Wei, Z. et al. Deacetylation of serine hydroxymethyl-transferase 2 by SIRT3 promotes colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat Commun. 9, 4468 (2018).

41.

Byrne, D. P. et al. cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) complexes probed by complementary differential scanning fluorimetry and ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Biochem. J. 473, 3159–3175 (2016).

42.

Scarff, C. A. et al. Examination of ataxin-3 (atx-3) aggregation by structural mass spectrometry techniques: a rationale for expedited aggregation upon polyglutamine (polyQ) expansion. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 1241–1253 (2015).

43.

Gault, J., et al. High-resolution mass spectrometry of small molecules bound to membrane proteins. Nat. Methods 13, 333–336 (2016).

44.

Rose, R. J., Damoc, E., Denisov, E., Makarov, A. & Heck, A. J. R. High-sensitivity Orbitrap mass analysis of intact macromolecular assemblies. Nat. Methods 9, 1084–1086 (2012).

45.

Marty, M. T. et al. Bayesian deconvolution of mass and ion mobility spectra: from binary interactions to polydisperse ensembles. Anal. Chem. 87, 4370–4376 (2015).

46.

Shao, G. et al. MERIT40 controls BRCA1–Rap80 complex integrity and recruitment to DNA double-strand breaks. Genes Dev. 23, 740–754 (2009).

47.

Ochocki, J. D. et al. Arginase 2 suppresses renal carcinoma progression via biosynthetic cofactor pyridoxal phosphate depletion and increased polyamine toxicity. Cell Metab. 27, 1263–1280.e6 (2018).

Source link

0 notes

Text

Porting Garcia-m NC

New Post has been published on https://nerret.com/netmyname/porting-garcia-m/porting-garcia-m-nc/

Porting Garcia-m NC

Porting Garcia-m NC Top Web Results.

imaging.onlinejacc.org NIRS and IVUS for Characterization of Atherosclerosis in Patients … elevated percentage VH-NC or LCP by NIRS; however, the correlation ….. 450 m and correlated with each chemogram block (4). For the validation of …. ported that false positive reading of NIRS could be …. Garcia–Garcia HM, Serruys PW,.

www.mt-llc.com Millennium Technologies Millennium Technologies provides repair and maintenance services for cylinders and cylinder heads, and manufactures nickel silicon carbide plated cylinders …

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov Mechanisms of Protein Sorting in Mitochondria Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 226–233 [PubMed]; Garcia M, Darzacq X, Delaveau T, ��� Hulett JM, Lueder F, Chan NC, Perry AJ, Wolynec P, Likic VA, Gooley PR, …

academic.oup.com Plant Biosecurity in the United States: Roles, Responsibilities, and … management of exotic pests, port-of-entry measures, and domestic …… Magarey RD, Fowler GA, Borchert DM, Sutton TB, Colunga-Garcia M,. Simpson JA. 2007.

arxiv.org In Praise of Artifice Reloaded: Caution with subjective image quality … Jan 30, 2018 … 1. arXiv:1801.09632v1 [q-bio.NC] 29 Jan 2018 … ical goal (Laparra et al., 2017; Martinez-Garcia et al., 2017). When using ….. Optimization of the width and am– plitude of the …. ported from the optimized case. The panel at the …

enforcement.trade.gov List of Foreign-Trade Zones by State Grantee: Board of Harbor Commissioners of the Port of Long Beach 4801 Airport Plaza … County of Merced 2222 M Street, Merced, CA 95340 ….. 1 S. Wilmington St., Raleigh, NC 27601. Emily Jones …. Mark Garcia (956) 682-4306. Fax (956) …

arxiv.org Geonic black holes and remnants in Eddington-inspired Born-Infeld … Apr 28, 2014 … Gonzalo J. Olmo a,1, D. Rubiera-Garcia b,2, Helios Sanchis-Alepuz c,3 … ported by the electric field. As a result, the total energy … low a critical value, Nc q ∼ 16 ….. The function M(r) appearing in (15) can be written as M(r) …

www.sportingnews.com Sporting News – NFL | NCAA | NBA | MLB | NASCAR | UFC | WWE Kevin Garnett sues accountant, alleging $77M stolen from him · Arthur Weinstein … Angel Garcia: The method behind the madness of Danny Garcia's father and.

www.karger.com Cebus apella, Cebus xanthosternos and Cebus nigr Oct 30, 2012 … Manuel Ruiz-García Maria Ignacia Castillo Nicolás Lichilín-Ortiz ….. 3 m M MgCl 2, 2 l of 1 m M dNTPs, 2 l (8 pmol) of each primer, 2 units of Taq DNA …… ported by this first molecular study. ….. Rambaut A, Grassly NC (1997).

ajph.aphapublications.org Small-Group Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase Condom Use … have sex with men, aged 18 to 55 years in North Carolina, to the 4-session HOLA en Grupos intervention or an ….. ported adherence to traditional notions of masculinity (P= …. R. Rodriguez-Celedon, and M. Garcia collected the data. L. Mann …

0 notes

Text

An integrated native mass spectrometry and top-down proteomics method that connects sequence to structure and function of macromolecular complexes

1.

Sharon, M. How far can we go with structural mass spectrometry of protein complexes? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 21, 487–500 (2010).

2.

Heck, A. J. R. Native mass spectrometry: a bridge between interactomics and structural biology. Nat. Methods 5, 927–933 (2008).

3.

Lorenzen, K. & Duijn, E. v. Current Protocols in Protein Science (Wiley, 2001).

4.

Van Duijn, E. Current limitations in native mass spectrometry based structural biology. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 21, 971–978 (2010).

5.

Benesch, J. L. P., Ruotolo, B. T., Simmons, D. A. & Robinson, C. V. Protein complexes in the gas phase: technology for structural genomics and proteomics. Chem. Rev. 107, 3544–3567 (2007).

6.

Snijder, J., Rose, R. J., Veesler, D., Johnson, J. E. & Heck, A. J. R. Studying 18 MDa virus assemblies with native mass spectrometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 4020–4023 (2013).

7.

Van Berkel, W. J. H., Van Den Heuvel, R. H. H., Versluis, C. & Heck, A. J. R. Detection of intact megaDalton protein assemblies of vanillyl-alcohol oxidase by mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 9, 435–439 (2000).

8.

Rose, R. J., Damoc, E., Denisov, E., Makarov, A. & Heck, A. J. R. High-sensitivity Orbitrap mass analysis of intact macromolecular assemblies. Nat. Methods 9, 1084–1086 (2012).

9.

Van de Waterbeemd, M. et al. High-fidelity mass analysis unveils heterogeneity in intact ribosomal particles. Nat. Methods 14, 283–286 (2017).

10.

Snijder, J. et al. Defining the stoichiometry and cargo load of viral and bacterial nanoparticles by orbitrap mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 7295–7299 (2014).

11.

Gault, J. et al. High-resolution mass spectrometry of small molecules bound to membrane proteins. Nat. Methods 13, 333–336 (2016).

12.

Dyachenko, A. et al. Tandem native mass-spectrometry on antibody–drug conjugates and submillion Da antibody–antigen protein assemblies on an Orbitrap EMR equipped with a high-mass quadrupole mass selector. Anal. Chem. 87, 6095–6102 (2015).

13.

Rosati, S., Yang, Y., Barendregt, A. & Heck, A. J. R. Detailed mass analysis of structural heterogeneity in monoclonal antibodies using native mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 9, 967–976 (2014).

14.

Walzthoeni, T., Leitner, A., Stengel, F. & Aebersold, R. Mass spectrometry supported determination of protein complex structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 252–260 (2013).

15.

Shi, Y. et al. Structural characterization by cross-linking reveals the detailed architecture of a coatomer-related heptameric module from the nuclear pore complex. Mol. Cell Proteomics 13, 2927–2943 (2014).

16.

Savaryn, J., Catherman, A., Thomas, P., Abecassis, M. & Kelleher, N. The emergence of top-down proteomics in clinical research. Genome Med. 5, 53 (2013).

17.

Smith, L. M. & Kelleher, N. L. Proteoform: a single term describing protein complexity. Nat. Methods 10, 186–187 (2013).

18.

Li, H. et al. Use of top-down and bottom-up Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry for mapping calmodulin sites modified by platinum anticancer drugs. Anal. Chem. 83, 9507–9515 (2011).

19.

Siuti, N. & Kelleher, N. L. Decoding protein modifications using top-down mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 817–821 (2007).

20.

Tian, Z. et al. Enhanced top-down characterization of histone post-translational modifications. Genome Biol. 13, R86 (2012).

21.

Xie, Y., Zhang, J., Yin, S. & Loo, J. A. Top-down ESI-ECD-FT-ICR mass spectrometry localizes noncovalent protein–ligand binding sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14432–14433 (2006).

22.

Castro, M. E., Russell, D. H., Amster, I. J. & McLafferty, F. W. Detection of mass 16241 ions by Fourier-transform mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 58, 483–485 (1986).

23.

Karabacak, N. M. et al. Sensitive and specific identification of wild type and variant proteins from 8 to 669 kDa using top-down mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell Proteomics 8, 846–856 (2009).

24.

Zhang, H., Cui, W., Gross, M. L. & Blankenship, R. E. Native mass spectrometry of photosynthetic pigment–protein complexes. FEBS Lett. 587, 1012–1020 (2013).

25.

Li, H., Wolff, J. J., Van Orden, S. L. & Loo, J. A. Native top-down electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry of 158 kDa protein complex by high-resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 86, 317–320 (2014).

26.

Li, H., Wongkongkathep, P., Van Orden, S., Ogorzalek Loo, R. & Loo, J. Revealing ligand binding sites and quantifying subunit variants of noncovalent protein complexes in a single native top-down FTICR MS experiment. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 25, 2060–2068 (2014).

27.

Zhang, H., Cui, W., Wen, J., Blankenship, R. E. & Gross, M. L. Native electrospray and electron-capture dissociation FTICR mass spectrometry for top-down studies of protein assemblies. Anal. Chem. 83, 5598–5606 (2011).

28.

Geels, R. B. J., van der Vies, S. M., Heck, A. J. R. & Heeren, R. M. A. Electron capture dissociation as structural probe for noncovalent gas-phase protein assemblies. Anal. Chem. 78, 7191–7196 (2006).

29.

Barford, D., Hu, S. H. & Johnson, L. N. Structural mechanism for glycogen phosphorylase control by phosphorylation and AMP. J. Mol. Biol. 218, 233–260 (1991).

30.

Horn, D. M., Ge, Y. & McLafferty, F. W. Activated ion electron capture dissociation for mass spectral sequencing of larger (42 kDa) proteins. Anal. Chem. 72, 4778–4784 (2000).

31.

Schennach, M. & Breuker, K. Probing protein structure and folding in the gas phase by electron capture dissociation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 26, 1059–1067 (2015).

32.

Johnson, L. N. Glycogen phosphorylase: control by phosphorylation and allosteric effectors. FASEB J. 6, 2274–2282 (1992).

33.

Tsaprailis, G., Somogyi, Á., Nikolaev, E. N. & Wysocki, V. H. Refining the model for selective cleavage at acidic residues in arginine-containing protonated peptides2. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 195–196, 467–479 (2000).

34.

Breci, L. A., Tabb, D. L., Yates, J. R. & Wysocki, V. H. Cleavage N-terminal to proline: analysis of a database of peptide tandem mass spectra. Anal. Chem. 75, 1963–1971 (2003).

35.

Rose, G., Geselowitz, A., Lesser, G., Lee, R. & Zehfus, M. Hydrophobicity of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Science 229, 834–838 (1985).

36.

Carrigan, J. B. & Engel, P. C. The structural basis of proteolytic activation of bovine glutamate dehydrogenase. Protein Sci. 17, 1346–1353 (2008).

37.

Banerjee, S., Schmidt, T., Fang, J., Stanley, C. A. & Smith, T. J. Structural studies on ADP activation of mammalian glutamate dehydrogenase and the evolution of regulation. Biochemistry 42, 3446–3456 (2003).

38.

Smith, T. J. & Stanley, C. A. Untangling the glutamate dehydrogenase allosteric nightmare. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 557–564 (2008).

39.

Jacobson, R. H., Zhang, X. J., DuBose, R. F. & Matthews, B. W. Three-dimensional structure of β-galactosidase from E. coli. Nature 369, 761–766 (1994).

40.

Matthews, B. W. The structure of E. coli β-galactosidase. C. R. Biol. 328, 549–556 (2005).

41.

Cui, W., Zhang, H., Blankenship, R. E. & Gross, M. L. Electron-capture dissociation and ion mobility mass spectrometry for characterization of the hemoglobin protein assembly. Protein Sci. 24, 1325–1332 (2015).

42.

Lermyte, F. et al. ETD allows for native surface mapping of a 150 kDa noncovalent complex on a commercial Q-TWIMS-TOF instrument. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 25, 343–350 (2014).

43.

Li, H. et al. Structural characterization of native proteins and protein complexes by electron ionization dissociation-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 89, 2731–2738 (2017).

44.

Jacob, E. & Unger, R. A tale of two tails: why are terminal residues of proteins exposed? Bioinformatics 23, e225–e230 (2007).

45.

van der Spoel, D., Marklund, E. G., Larsson, D. S. D. & Caleman, C. Proteins, lipids, and water in the gas phase. Macromol. Biosci. 11, 50–59 (2011).

46.

Faull, P. A. et al. Gas-phase metalloprotein complexes interrogated by ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 283, 140–148 (2009).

47.

Haverland, N. A. et al. Defining gas-phase fragmentation propensities of intact proteins during native top-down mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 28, 1203–1215 (2017).

48.

Brodbelt, J. S. & Wilson, J. J. Infrared multiphoton dissociation in quadrupole ion traps. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 28, 390–424 (2009).

49.

Bourgoin-Voillard, S., Leymarie, N. & Costello, C. E. Top-down tandem mass spectrometry on RNase A and B using a Qh/FT-ICR hybrid mass spectrometer. Proteomics 14, 1174–1184 (2014).

50.

Ahlf, D. et al. Evaluation of the compact high-field Orbitrap for top-down proteomics of human cells. J. Proteome Res. 11, 4308–4314 (2012).

51.

Holzmann, J., Hausberger, A., Rupprechter, A. & Toll, H. Top-down MS for rapid methionine oxidation site assignment in filgrastim. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 6667–6674 (2013).

52.

Belov, M. E. et al. From protein complexes to subunit backbone fragments: a multi-stage approach to native mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 85, 11163–11173 (2013).

53.

Brodbelt, J. S. Ion activation methods for peptides and proteins. Anal. Chem. 88, 30–51 (2016).

54.

Durbin, K. R., Skinner, O. S., Fellers, R. T. & Kelleher, N. L. Analyzing internal fragmentation of electrosprayed ubiquitin ions during beam-type collisional dissociation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 26, 782–787 (2015).

55.

Ogorzalek Loo, R. R. & Loo, J. A. Protein complexes: breaking up is hard to do well. Structure 21, 1265–1266 (2013).

56.

Schennach, M. & Breuker, K. Proteins with highly similar native folds can show vastly dissimilar folding behavior when desolvated. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 164–168 (2014).

57.

Campuzano, I. & Giles, K. Nanoproteomics: Methods and Protocols (eds Toms, S.A. & Weil, R.J.) 57–70 (Humana, 2011).

58.

Marshall, A. G., Hendrickson, C. L. & Jackson, G. S. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: a primer. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 17, 1–35 (1998).

59.

Rayleigh, L. XX. On the equilibrium of liquid conducting masses charged with electricity. Philos. Mag. 14, 184–186 (1882).

60.

Ma, X., Zhou, M. & Wysocki, V. Surface induced dissociation yields quaternary substructure of refractory noncovalent phosphorylase B and glutamate dehydrogenase complexes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 25, 368–379 (2014).

61.

Rostom, A. A. & Robinson, C. V. Detection of the intact GroEL chaperonin assembly by mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 4718–4719 (1999).

62.

Sobott, F. & Robinson, C. V. Characterising electrosprayed biomolecules using tandem-MS—the noncovalent GroEL chaperonin assembly. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 236, 25–32 (2004).

63.

Zubarev, R. A. Electron-capture dissociation tandem mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15, 12–16 (2004).

— Nature Chemistry

#Nature Chemistry#An integrated native mass spectrometry and top-down proteomics method that connect

0 notes

Text

lnc-β-Catm elicits EZH2-dependent β-catenin stabilization and sustains liver CSC self-renewal.

Latest HPB article: [LIVER] http://dlvr.it/LRjhpZ

0 notes

Text

The ribosome moves: #RNA mechanics and translocation.

Related Articles The ribosome moves: #RNA mechanics and translocation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017 Dec 07;24(12):1021-1027 Authors: Noller HF, Lancaster L, Zhou J, Mohan S Abstract During protein synthesis, #mRNA and #tRNAs must be moved rapidly through the ribosome while maintaining the translational reading frame. This process is coupled to large- and small-scale conformational rearrangements in the ribosome, mainly in its #rRNA. The free energy from peptide-bond formation and GTP hydrolysis is probably used to impose directionality on those movements. We propose that the free energy is coupled to two pawls, namely #tRNA and EF-G, which enable two ratchet mechanisms to act separately and sequentially on the two ribosomal subunits. PMID: 29215639 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] http://bit.ly/2Cp3LYB #Pubmed

0 notes

Text

Guide-bound structures of an #RNA-targeting A-cleaving CRISPR-Cas13a enzyme.

Related Articles Guide-bound structures of an #RNA-targeting A-cleaving CRISPR-Cas13a enzyme. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017 Oct;24(10):825-833 Authors: Knott GJ, East-Seletsky A, Cofsky JC, Holton JM, Charles E, O'Connell MR, Doudna JA Abstract CRISPR adaptive immune systems protect bacteria from infections by deploying CRISPR #RNA (c#rRNA)-guided enzymes to recognize and cut foreign nucleic acids. Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas systems include the Cas13a enzyme, an #RNA-activated RNase capable of c#rRNA processing and single-stranded #RNA degradation upon target-transcript binding. Here we present the 2.0-Å resolution crystal structure of a c#rRNA-bound Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas13a (LbaCas13a), representing a recently discovered Cas13a enzyme subtype. This structure and accompanying biochemical experiments define the Cas13a catalytic residues that are directly responsible for c#rRNA maturation. In addition, the orientation of the foreign-derived target-#RNA-specifying sequence in the protein interior explains the conformational gating of Cas13a nuclease activation. These results describe how Cas13a enzymes generate functional c#rRNAs and how catalytic activity is blocked before target-#RNA recognition, with implications for both bacterial immunity and diagnostic applications. PMID: 28892041 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] http://bit.ly/2gGCp6O #Pubmed

0 notes

Text

Structure of a transcribing #RNA polymerase II-DSIF complex reveals a multidentate DNA-#RNA clamp.

Related Articles Structure of a transcribing #RNA polymerase II-DSIF complex reveals a multidentate DNA-#RNA clamp. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017 Oct;24(10):809-815 Authors: Bernecky C, Plitzko JM, Cramer P Abstract During transcription, #RNA polymerase II (Pol II) associates with the conserved elongation factor DSIF. DSIF renders the elongation complex stable and functions during Pol II pausing and #RNA processing. We combined cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of the mammalian Pol II-DSIF elongation complex at a nominal resolution of 3.4 Å. Human DSIF has a modular structure with two domains forming a DNA clamp, two domains forming an #RNA clamp, and one domain buttressing the #RNA clamp. The clamps maintain the transcription bubble, position upstream DNA, and retain the #RNA transcript in the exit tunnel. The mobile C-terminal region of DSIF is located near exiting #RNA, where it can recruit factors for #RNA processing. The structure provides insight into the roles of DSIF during #mRNA synthesis. PMID: 28892040 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] http://bit.ly/2gI3lTu #Pubmed

0 notes

Text

NEAT1 scaffolds #RNA-binding proteins and the Microprocessor to globally enhance pri-#miRNA processing.

Related Articles NEAT1 scaffolds #RNA-binding proteins and the Microprocessor to globally enhance pri-#miRNA processing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017 Oct;24(10):816-824 Authors: Jiang L, Shao C, Wu QJ, Chen G, Zhou J, Yang B, Li H, Gou LT, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Yeo GW, Zhou Y, Fu XD Abstract Micro#RNA (#miRNA) biogenesis is known to be modulated by a variety of #RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), but in most cases, individual RBPs appear to influence the processing of a small subset of target #miRNAs. Here, we report that the #RNA-binding NONO-PSF heterodimer binds a large number of expressed pri-#miRNAs in HeLa cells to globally enhance pri-#miRNA processing by the Drosha-DGCR8 Microprocessor. NONO and PSF are key components of paraspeckles organized by the long noncoding #RNA (l#ncRNA) NEAT1. We further demonstrate that NEAT1 also has a profound effect on global pri-#miRNA processing. Mechanistic dissection reveals that NEAT1 broadly interacts with the NONO-PSF heterodimer as well as many other RBPs and that multiple #RNA segments in NEAT1, including a 'pseudo pri-#miRNA' near its 3' end, help attract the Microprocessor. These findings suggest a 'bird nest' model in which an l#ncRNA orchestrates efficient processing of potentially an entire class of small noncoding #RNAs in the nucleus. PMID: 28846091 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] http://bit.ly/2gHEsY5 #Pubmed

0 notes

Text

NEAT1 scaffolds #RNA-binding proteins and the Microprocessor to globally enhance pri-#miRNA processing.

Related Articles NEAT1 scaffolds #RNA-binding proteins and the Microprocessor to globally enhance pri-#miRNA processing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017 Oct;24(10):816-824 Authors: Jiang L, Shao C, Wu QJ, Chen G, Zhou J, Yang B, Li H, Gou LT, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Yeo GW, Zhou Y, Fu XD Abstract Micro#RNA (#miRNA) biogenesis is known to be modulated by a variety of #RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), but in most cases, individual RBPs appear to influence the processing of a small subset of target #miRNAs. Here, we report that the #RNA-binding NONO-PSF heterodimer binds a large number of expressed pri-#miRNAs in HeLa cells to globally enhance pri-#miRNA processing by the Drosha-DGCR8 Microprocessor. NONO and PSF are key components of paraspeckles organized by the long noncoding #RNA (l#ncRNA) NEAT1. We further demonstrate that NEAT1 also has a profound effect on global pri-#miRNA processing. Mechanistic dissection reveals that NEAT1 broadly interacts with the NONO-PSF heterodimer as well as many other RBPs and that multiple #RNA segments in NEAT1, including a 'pseudo pri-#miRNA' near its 3' end, help attract the Microprocessor. These findings suggest a 'bird nest' model in which an l#ncRNA orchestrates efficient processing of potentially an entire class of small noncoding #RNAs in the nucleus. PMID: 28846091 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] http://bit.ly/2gHEsY5 #Pubmed

0 notes

Video

vimeo

"ZNF-451 E3 SUMO Ligase, as Putative Partner for MAPKK-RNF4 Signaling Complex", Hypothesis and Project by Alex Sobko, PhD from Alexander Sobko on Vimeo.

ZNF-451 E3 SUMO Ligase, as Putative Partner for MAPKK-RNF4 Signaling Complex - A Hypothesis and New Project” by Dr. Alex Sobko, PhD

Copyright:

© 2022, Alex Sobko, PhD © 2022, Record, edit, design, posts at social media by Alex Sobko, PhD, 8762728, South-West IL (ישראל).

References:

Sobko A. A hypothetical MEK1-MIP1-SMEK multiprotein signaling complex may function in Dictyostelium and mammalian cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2020;64(10-11-12):495-498.

Sobko A, Ma H, Firtel RA. Regulated SUMOylation and ubiquitination of DdMEK1 is required for proper chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2002 Jun;2(6):745-56.

Eisenhardt N.…Pichler A. A new vertebrate SUMO enzyme family reveals insights into SUMO-chain assembly. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015 Dec;22(12):959-67.

Koidl S.…Pichler A. The SUMO2/3 specific E3 ligase ZNF451-1 regulates PML stability. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016 Oct; 79:478-487.

Cuijpers SAG, Willemstein E, Vertegaal ACO. Converging Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) and Ubiquitin Signaling: Improved Methodology Identifies Co-modified Target Proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017 Dec;16(12):2281-2295.

Bigenzahn JW…Superti-Furga G. LZTR1 is a regulator of RAS ubiquitination and signaling. Science. 2018 Dec 7;362(6419):1171-1177.

Steklov M…Sablina AA. Mutations in LZTR1 drive human disease by dysregulating RAS ubiquitination. Science. 2018 Dec 7;362(6419):1177-1182.

youtu.be/35NqAbc3VQs

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Lecture: "Cell biologist’s perspective. Frontiers in Development of HDAC Degraders. by Alex Sobko, PhD. May 2022. from Alexander Sobko on Vimeo.

Lecture: "Cell biologist’s perspective. Frontiers in Development of HDAC Degraders. by Alex Sobko, PhD. May 2022.

© 2022, Alex Sobko, PhD © 2022, Record, edit, post at social media by Alex Sobko, PhD, 8762728 IL (ישראל)

References and Textbooks:

Epigenetics, Cancer, Aging

Ageless Quest: One Scientist's Search for the Genes That Prolong Youth. Leonard Guarente. CSHL Press, 2002.

Lifespan: Why We Age―and Why We Don't Have To. David A. Sinclair PhD, Matthew D. LaPlante. 2019.

Lewin’s Genes XII. Krebs, Jocelyn E., Goldstein, Elliott S., Kilpatrick, Stephen T. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2018.

Epigenetics, Second Edition, Edited by C. David Allis et al, CSHL Press. © 2015. Chapter 4. Writers and Readers of Histone Acetylation: Structure, Mechanism, and Inhibition. Ronen Marmorstein, Ming-Ming Zhou. Chapter 5. Erasers of Histone Acetylation: The Histone Deacetylase Enzymes. Edward Seto, Minoru Yoshida. Chapter 34. Epigenetic Determinants of Cancer. Stephen B. Baylin, Peter A. Jones. Chapter 35. Histone Modifications and Cancer. James E. Audia Robert M. Campbell. Epigenetics and Cancer.

Feinberg AP, Koldobskiy MA, Göndör A. Epigenetic modulators, modifiers and mediators in cancer aetiology and progression. Nat Rev Genet. 2016 May;17(5):284-99.

Zhao S, Allis CD, Wang GG. The language of chromatin modification in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021 Jul;21(7):413-430.

Cynthia J. Kenyon. The genetics of ageing. Nature, 2010, 464, 504. Cell 166, 2016.

Payel Sen, Parisha P. Shah, Raffaella Nativio, and Shelley L. Berger. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Longevity and Aging. Cell 2016, 166, 822-839.

Molecular degraders

Alessio Ciulli and Nicole Trainor. A beginner’s guide to PROTACs and targeted protein degradation. October 2021 © The Authors. Portland Press Limited under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND).

Stuart L. Schreiber. The Rise of Molecular Glues. Cell 2021, 184. Rati Verma, Dane Mohl, and Raymond J. Deshaies. Harnessing the Power of Proteolysis for Targeted Protein Inactivation. Molecular Cell, 2020, 77.

Wu, T., Yoon, H., Xiong, Y. et al. Targeted protein degradation as a powerful research tool in basic biology and drug target discovery. Nat Struct Mol Biol 27, 605–614 (2020).

HDAC Inhibitors, HDAC-degraders

EPIGENETIC THERAPY WITH HISTONE DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS: IMPLICATIONS FOR CANCER TREATMENT. Soares, C. P., Santos, J. L. D., Sousa, Â., eds. (2021). Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA. (Front Cell Dev Biol).

Jia Tong Loh, I-hsin Su. Post-translational modification-regulated leukocyte adhesion and migration. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(24), 37347-37360.

Sobko A. Cell biologist’s perspective: Frontiers in Development of PROTAC-HDAC degraders. Preprint. August 2021. doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/vua9r.

Rodrigues DA, Roe A, Griffith D, Chonghaile TN. Advances in the Design and Development of PROTAC-mediated HDAC Degradation. Curr Top Med Chem. 2022 Mar 4;22(5):408-424.

Rodrigues DA, Pedro de S. M. Pinheiro, Fernanda S. Sagrillo, Maria L. Bolognesi, Carlos A. M. Fraga. Histone deacetylases as targets for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders: Challenges and future opportunities. Med Res Rev. 2020; 1–35.

Durbin AD, Wang T, Wimalasena VK, Zimmerman MW, Li D, Dharia NV, Mariani L, Shendy NAM, Nance S, Patel AG, Shao Y, Mundada M, Maxham L, Park PMC, Sigua LH, Morita K, Conway AS, Robichaud AL, Perez-Atayde AR, Bikowitz MJ, Quinn TR, Wiest O, Easton J, Schönbrunn E, Bulyk ML, Abraham BJ, Stegmaier K, Look AT, Qi J. EP300 Selectively Controls the Enhancer Landscape of MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma. Cancer Discov. 2022 Mar 1;12(3):730-751.

0 notes

Video

Lecture: "Cell biologist’s perspective: Frontiers in Development of HDAC Degraders", by Alex Sobko, PhD, May 2022. from Alexander Sobko on Vimeo.

Lecture: "Cell biologist’s perspective. Frontiers in Development of HDAC Degraders. by Alex Sobko, PhD. May 2022.

© 2022, Alex Sobko, PhD © 2022, Record, edit, post at social media by Alex Sobko, PhD, 8762728 IL (ישראל)

References and Textbooks:

Epigenetics, Cancer, Aging

Ageless Quest: One Scientist's Search for the Genes That Prolong Youth. Leonard Guarente. CSHL Press, 2002.

Lifespan: Why We Age―and Why We Don't Have To. David A. Sinclair PhD, Matthew D. LaPlante. 2019.

Lewin’s Genes XII. Krebs, Jocelyn E., Goldstein, Elliott S., Kilpatrick, Stephen T. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2018.

Epigenetics, Second Edition, Edited by C. David Allis et al, CSHL Press. © 2015. Chapter 4. Writers and Readers of Histone Acetylation: Structure, Mechanism, and Inhibition. Ronen Marmorstein, Ming-Ming Zhou. Chapter 5. Erasers of Histone Acetylation: The Histone Deacetylase Enzymes. Edward Seto, Minoru Yoshida. Chapter 34. Epigenetic Determinants of Cancer. Stephen B. Baylin, Peter A. Jones. Chapter 35. Histone Modifications and Cancer. James E. Audia Robert M. Campbell. Epigenetics and Cancer.

Feinberg AP, Koldobskiy MA, Göndör A. Epigenetic modulators, modifiers and mediators in cancer aetiology and progression. Nat Rev Genet. 2016 May;17(5):284-99.

Zhao S, Allis CD, Wang GG. The language of chromatin modification in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021 Jul;21(7):413-430.

Cynthia J. Kenyon. The genetics of ageing. Nature, 2010, 464, 504. Cell 166, 2016.

Payel Sen, Parisha P. Shah, Raffaella Nativio, and Shelley L. Berger. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Longevity and Aging. Cell 2016, 166, 822-839.

Molecular degraders

Alessio Ciulli and Nicole Trainor. A beginner’s guide to PROTACs and targeted protein degradation. October 2021 © The Authors. Portland Press Limited under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND).

Stuart L. Schreiber. The Rise of Molecular Glues. Cell 2021, 184. Rati Verma, Dane Mohl, and Raymond J. Deshaies. Harnessing the Power of Proteolysis for Targeted Protein Inactivation. Molecular Cell, 2020, 77.

Wu, T., Yoon, H., Xiong, Y. et al. Targeted protein degradation as a powerful research tool in basic biology and drug target discovery. Nat Struct Mol Biol 27, 605–614 (2020).

HDAC Inhibitors, HDAC-degraders

EPIGENETIC THERAPY WITH HISTONE DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS: IMPLICATIONS FOR CANCER TREATMENT. Soares, C. P., Santos, J. L. D., Sousa, Â., eds. (2021). Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA. (Front Cell Dev Biol).

Jia Tong Loh, I-hsin Su. Post-translational modification-regulated leukocyte adhesion and migration. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(24), 37347-37360.

Sobko A. Cell biologist’s perspective: Frontiers in Development of PROTAC-HDAC degraders. Preprint. August 2021. doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/vua9r.

Rodrigues DA, Roe A, Griffith D, Chonghaile TN. Advances in the Design and Development of PROTAC-mediated HDAC Degradation. Curr Top Med Chem. 2022 Mar 4;22(5):408-424.

Rodrigues DA, Pedro de S. M. Pinheiro, Fernanda S. Sagrillo, Maria L. Bolognesi, Carlos A. M. Fraga. Histone deacetylases as targets for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders: Challenges and future opportunities. Med Res Rev. 2020; 1–35.

Durbin AD, Wang T, Wimalasena VK, Zimmerman MW, Li D, Dharia NV, Mariani L, Shendy NAM, Nance S, Patel AG, Shao Y, Mundada M, Maxham L, Park PMC, Sigua LH, Morita K, Conway AS, Robichaud AL, Perez-Atayde AR, Bikowitz MJ, Quinn TR, Wiest O, Easton J, Schönbrunn E, Bulyk ML, Abraham BJ, Stegmaier K, Look AT, Qi J. EP300 Selectively Controls the Enhancer Landscape of MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma. Cancer Discov. 2022 Mar 1;12(3):730-751.

0 notes

Text

Tapping the #RNA_World for therapeutics.

Related Articles Tapping the #RNA_World for therapeutics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018 05;25(5):357-364 Authors: Lieberman J Abstract A recent r#evolution in #RNA biology has led to the identification of new #RNA classes with unanticipated functions, new types of #RNA modifications, an unexpected multiplicity of alternative transcripts and widespread transcription of extragenic regions. This development in basic #RNA biology has spawned a corresponding r#evolution in #RNA-based strategies to generate new types of therapeutics. Here, I review #RNA-based drug design and discuss barriers to broader applications and possible ways to overcome them. Because they target nucleic acids rather than proteins, #RNA-based drugs promise to greatly extend the domain of 'druggable' targets beyond what can be achieved with small molecules and biologics. PMID: 29662218 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE] http://bit.ly/2Z6sMS2

0 notes