#NOT saying movie once-ler isn't cute/cool (just bland in contrast to being a disembodied pair of mysterious arms)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

At least 76% plastic

I’m a consummate defender of Ron Howard’s live-action Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000)—and, to a much lesser extent, Bo Welch’s 2003 Dr. Seuss’ The Cat in the Hat—not because I think the movie/either movie is particularly “good” but because they are at least not boring. They have an interesting chaotic and even gross energy. I guess there’s a case to be made for them having camp value since the ostensible intent was to mimic the iconic whimsy and color of a Seuss book, but the end-results are just trippy, uncanny, horny, racist, etc. Jim Carrey and Mike Myers are great as the Grinch and Cat, respectively, but I don’t think for the intended reasons.

Meanwhile, the 2012 Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax (another kids’ movie I skipped originally) is just boring and lacks even the off-putting (accidental?) artistry of the aforementioned two live-action movies. Watching it, I felt exactly what I’ve frequently seen other people decry about Howard’s Grinch: That it’s too long, for one thing, spoiling the pristine pacing of the Seuss original and the earlier animated adaptation, which is like a third to a fourth of this newer runtime. The difference is that I find stuff like the Whos throwing a key party delightful but think the many little moments of additional “whimsy” Illumination tries to cram into Lorax are unpalatable violations of the original work’s mood. The difference is almost purely subjective, of course, but I would still argue for The Grinch treatment being more interesting because it is such a wild, wide swing (and a miss). Meanwhile, the added stuff of The Lorax is very safe and sanitized and is just mostly comprised of goofiness that children would probably enjoy (trademark). It is, ironically, as texture-less and vapid as the corporate-controlled façade and endless profiteering the movie supposedly critiques.

One visual that I actually liked was the design of the very important Truffula Trees. Their colorful tufts looked so pleasant to touch (and maybe delicious). Their allure—to the animals, to the Once-ler for his “Thneed”-making, to the deprived people of the flimsy utopia of “Thneedville” as a symbol of hope—is perfectly, primally presented. And the movie kind of does justice to the aged Once-ler’s house, at least on its first appearance, when it’s meant to be ominous, though that feeling does not stick around for subsequent scenes or even for that entire initial visit once The Whimsy kicks in.

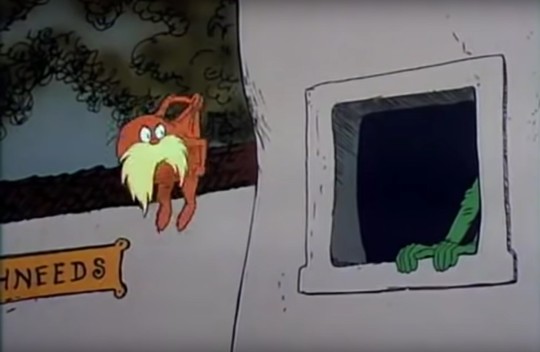

I have always been drawn to horror, and the Once-ler and his house as depicted in the Seuss book are early images in that vein that I still feel on a deep, subconscious level. I loved how the book reduces the Once-ler to just his long arms, keeping the body hidden. Of course, The Lorax movie as good as resents suggestion/implication and requires a maximalist telling to make the story fit the feature film outline. The child from the book’s frame narrative now has his own story that trades off with the Once-ler’s, and the two arcs muddy the waters greatly in terms of pathos. There’s a new, additional profiteering capitalist, Mr. O’Hare, to serve as an antagonist for the story, where the original book was more of a parable and less of a conventional narrative with such rote dramatic stakes. The way that it concluded so ambiguously by exhorting the frame narrative child (and, by extension, the reader) to be better than the Once-ler without ending on a conventionally “happy” note is part of what gives it so much force and staying power (and contributes to The Gloom that I enjoyed). I resent the movie’s de-fanging of the original narrative’s criticism by virtue of being too damn long and boring—Because the Once-ler’s story now ends before the movie does, he has to offer the exhortation/moral too early, so they also slap those words on-screen again when the movie finally does actually conclude, with the Once-ler and Lorax embracing as friends. The world gets better because Ted Wiggins cares a lot; you, the viewer, need not feel so terribly pressed to do anything.

Depicting the Once-ler at all is a mistake, and not just because his bland human design sucks all the mystery and fun out of the character. It also bungles his thematic purpose: He is the Once-ler, an embodiment of the mistakes of the past, passing his story and the hope for the future onto his audience. Who he was is unimportant (you could argue that he’s not one person so much as a whole generation and/or class of people), and what matters is strictly what he did (wrong). He and his name are allegorical and vague. We’re not meant to latch onto him and to instead find something familiar and relatable in the child as our proxy. By contrast, the movie now asks us to root for and empathize with the Once-ler as well, and now he’s a concrete personality who was for some reason named “Once-ler” by his parents, which is just extremely odd, even more so when you throw in the stereotypically redneck-esque brothers named “Chet” and “Brett.”

Giving the Once-ler’s audience a name and an arc further dilutes the thematic and atmospheric power of the book, as that nameless kid is now “Ted Wiggins” specifically and no longer all of us. Giving him a motivation for visiting the Once-ler is also bad. In the book, we don’t know all the details regarding why the child is seeking this man-person-thing out, but it works in a very emotionally graspable way: It’s the haunted house, the neighborhood hermit (Old Man Once-ler), a novelty, maybe a dare or rite of passage of sorts. It can, in its vagueness, work with so many different storytelling concepts or frameworks involving children and local spooky mysteries. Having this “Ted” go to the Once-ler because he needs a tree in order to Get With Taylor Swift just feels like sacrilege, on top of being more vibe-wrecking specificity.

What I will give this narrative thread is that I think Ted subtly forgets this motivation in the end in a way that I actually liked: When he finally gets to plant the seed of the last Truffula Tree in the center of Thneedville (after a sequence of animated Antics that includes a radical snowboarding granny!), he’s so lost in the moment that he’s surprised when Swift’s Audrey gives him a peck on the cheek. Shortly before that, he also borrows the Lorax’s language in trying to win over the town by “speak[ing] for the trees.” I wish there was perhaps more of a spotlight placed on this transformation—how Ted doesn’t really care about trees initially (they’re just a means to an end, like they were for the Once-ler)—but he ultimately realizes that the health of the planet matters more than some mammalian milestone. The arc’s there, but it could have been drawn out as a new explicit moral that could have worked with this slick, modern Lorax, as one for the Smartphone Age youth, as it were. I am ultimately saying that this adaptation needed to change even more to function properly as a successor to the original.

The very beginning of The Lorax lulled me into a false sense of hope regarding the overall package, as there’s a movie-original rhyming bit delivered by the Lorax to set the stage that I felt matched ok enough with the source material, but I wish there was more that felt so effortful about this re-telling. There’s some “clever” incorporation of Seuss’ original words at points, and there are also some musical numbers that did not impress me on the first viewing. I lowered the volume a few notches for each one of them, in fact.

I didn’t (and still don’t) think any of these songs needed to be here, though I’ve changed my mind about them feeling what I was going to describe as “perfunctory.” That “you feel every song in [the movie] as a song first and foremost.” The comparison I was going to make was to musical theater, where what you want from a musical number is for the sentiment it expresses or the way that it advances the plot or deepens the audience’s understanding of a character to feel seamless—When you forget that the characters are even singing because it’s such a natural extension of the storytelling that it sweeps you away. Some of the musical numbers in The Lorax are even staged a bit like musical musical numbers, funnily enough. That’s a certain stylization I can respect. And they’ve grown on me over time (and after a second viewing), which also parallels my experience with musicals like Into the Woods. There was a “hollow, like a dead tree” final pronouncement attached to this train of thought originally, but I’m going to amend that slightly: Like a stricken, dying, or dead tree, there are fleeting glimpses of beauty or old grandeur in The Lorax, but also those tell-tale dead branches and unsightly growths that tell you the thing is not totally healthy.

#NOT saying movie once-ler isn't cute/cool (just bland in contrast to being a disembodied pair of mysterious arms)#movies#movie review#the lorax#lorax 2012#dr seuss

5 notes

·

View notes