#NIBR

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

IBR,NIBR and PNG Piping installations and erection In India

We have an extensive experience of executing underground and aboveground Piping projects involving Fabrication and Erection of IBR/ NIBR Pipelines in CS & SS, Process Piping for Chemical, Power, Cement, Mining, Pharmaceuticals and Steel Industry, including fabrication of Piperacks.

For more details please visit our website-

https://avengineersefp.com/service/piping-erection/

0 notes

Text

Lease or Buy Spaces in 1 Aerocity by FloorTap

NIBR 1 Aerocity, located in Andheri East, Mumbai, is a premier commercial project offering 202 well-ventilated units designed to meet the needs of both emerging and established businesses. Spread over a substantial area, the project provides versatile workspace solutions with a compliance-focused design. Situated in the vibrant Aerocity area, the development benefits from excellent infrastructure and a dynamic business atmosphere, making it an inviting prospect for organizations looking to thrive.

Strategically positioned in Andheri East, NIBR 1 Aerocity offers unparalleled accessibility and connectivity. The location is adjacent to Mumbai’s international airport, ensuring convenience for businesses with global operations. It is well-connected via the Mumbai Metro, suburban railways, buses, and major roadways, including the Western Express Highway and Andheri-Kurla Road. This excellent transport network facilitates easy commutes for employees and seamless logistics for businesses.

The architectural design of NIBR 1 Aerocity stands out with its distinctive glass façade and modern office interiors. The project is equipped with premium amenities such as valet parking, a business lounge, and concierge services, elevating its appeal as a sophisticated commercial destination. With top-notch infrastructure and professional management, the development creates a productive and stylish working environment.

For investors, NIBR 1 Aerocity presents a compelling opportunity. Its prime location in Andheri East, coupled with exceptional infrastructure and premium amenities, ensures high demand for workspace solutions. Flexible layouts, wet-line provisions, and inspiring views add to its versatility, catering to diverse business requirements. This strategic investment offers significant potential for long-term growth and steady returns in Mumbai’s thriving commercial real estate market.

0 notes

Text

fujcking shoot me

0 notes

Text

Tracklist:

El Chupa Nibre • Sofa King • The Mask • Perfect Hair • Benzie Box • Old School • A.T.H.F. • Basket Case • No Names • Crosshairs • Mince Meat • Vats of Urine • Space Ho's • Bada Bing

Spotify ♪ Bandcamp ♪ YouTube

#hyltta-polls#polls#artist: dangerdoom#artist: mf doom#artist: danger mouse#language: english#decade: 2000s#Abstract Hip Hop#East Coast Hip Hop#Nerdcore Hip Hop#Sketch Comedy#Experimental

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

DANGER DOOM - The Mouse and the Mask [2005]

Hip-Hop ; 39:51

El Chupa Nibre

Sofa King

The Mask (Feat. Ghostface Killah)

Perfect Hair

Benzie Box (Feat. Cee Lo Green)

Old School (Feat. Talib Kweli)

A.T.H.F.

Basket Case

No Names

Crosshairs

Mince Meat

Vats of Urine

Space Ho's

Bada Bing

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since announcing his presidential bid, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has made being “tough-on-crime” a cornerstone of his campaign. As purported proof of his track-record on public safety, he’s claimed that Florida “leads the nation” in crime reduction and is experiencing 50-year crime lows.

At the same time, he’s criticized “big progressive cities,” like Chicago, Philadelphia and Portland, Or. and blamed their justice reform policies for crime, while arguing that Florida’s pro-law enforcement stance is responsible for its relative safety.

The problem with these claims is that they are not only factually inaccurate, they also show just how little the presidential hopeful knows about crime in his own state—let alone the nation’s. DeSantis’ arguments deserve further investigation because they rely on inaccurate data that don’t (and can’t) paint the full picture of crime in Florida, obscures place-based variations and upticks in certain forms of crime across Florida, and contradicts the evidence on the relationship between criminal justice reform and crime.

Florida’s crime data are too flawed to claim 50-year lows

DeSantis can’t be sure that Florida has achieved 50-year crime rate lows because the state itself doesn’t know what its crime trends are, due to flawed data.

This is because, in 2021, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) was in the process of shifting from its traditional data collection system—the Summary Reporting System, which reports monthly crime counts and documents only the most serious offense in an incident—to align with new national FBI reporting standards, the National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS), which includes a greater number of crimes and allows for the reporting multiple offenses within one incident. While the NIBRS system will be an important transition in the long-term for more accurate crime reporting nationwide, some state agencies, including FDLE, did not meet the FBI’s 2021 reporting deadline and were excluded from national crime statistics.

In the place of accurate FBI data, DeSantis is basing his claims about Florida’s crime rates on FDLE’s 2021 annual crime report. This report is methodologically flawed since a total of 239 agencies (covering about half the state’s population) reported their crime trends using the old Summary Reporting System methodology. Others submitted with the new NIBRS methodology, others did a mix of both, and some—including Hillsborough County, where Tampa is—didn’t enter data whatsoever, meaning they were excluded from the 2021 statewide crime trends that DeSantis regularly cites.

These methodological clashes in Florida’s crime reporting create gaps in information that make it difficult to definitively claim any statewide crime trends—let alone that the state has reached “50-year-crime rate lows.”

Florida cities lagged behind more “progressive” cities in crime reduction

DeSantis’ “tough-on-crime” rhetoric relies on state-level “total crime” data to argue that Florida outperforms more progressive places (particularly cities) in crime reduction. Even if Florida’s state-level data was accurate, this comparison wouldn’t make sense for two reasons.

First, it compares Florida’s state-level data with cities, while ignoring place-based patterns of crime concentration within Florida itself. Meaning, DeSantis’ claims don’t acknowledge the “neutralizing” effect that state data can have on crime trends, if some Florida cities experienced sharp upticks in crime while others saw declines.

Second, DeSantis’ claims rely on statewide “total crime” rates, which can also be misleading if certain minor crimes (like shoplifting or drug possession) went down across the state, while more serious crimes (like murder or rape) went up.

To help determine whether Florida cities have truly made progress in reducing serious crimes—and to see how they stand up to “more progressive” peers—we analyzed local police department data from the state’s four largest cities’ and compared their crime reduction rates with four other cities (Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Richmond, California) that are relatively “progressive” on criminal justice, many of which have shouldered their share of criticisms from DeSantis.

Our analysis finds that place matters when talking about crime trends, and the story DeSantis is telling about the state of Florida versus “big progressive cities” in other states is much more complex than he makes it seem.

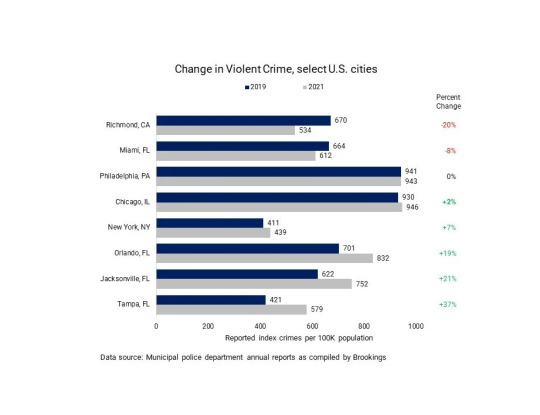

Looking at changes in violent crime rates between 2019 (the year DeSantis took office) and 2021 (the most recent year data were available), we found that three of Florida’s largest cities—Jacksonville, Tampa, and Orlando—had significant upticks in violent crime. Tampa led the bunch with a 37% spike, then Jacksonville at 21%, and Orlando at 19%. Miami, on the other hand, saw its violent crime rate decrease by 8%.

Looking at other cities deemed “progressive” on criminal justice—Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Richmond, Ca.—all made more progress on reducing violent crime rates than Tampa, Jacksonville, and Orlando.

For instance, Richmond— which has embraced public health and community violence intervention approaches to reducing crime—reduced its violent crime rate by 20% during this period (during which violent crimes were spiking nationwide).

And New York City—one of DeSantis’ favorite targets and a city that has, for decades, championed safety through environmental design (such as cleaning up public spaces and train stations)—had the lowest violent crime rate of any in the sample in 2021 at 439 violent crimes per 100,000 people compared to Orlando’s 832 violent crimes per 100,000 people.

Our analysis makes it clear that there is no one “statewide” story that can be told about crime—and that many of Florida’s largest cities are not achieving the violent crime reductions that DeSantis claims.

“Progressive” criminal justice reform policies do not cause crime

DeSantis’ “tough-on-crime” message hinges on blaming progressive criminal justice reforms, like ending cash bail or electing a progressive prosecutor, for rising crime rates.

But the evidence on the relationship between criminal justice reform and crime rates do not support his claims. New York’s 2019 bail reform legislation, for instance, was found to have a negligible effect on crime rates. Progressive prosecution practices in cities like Philadelphia, too, have not led to crime increases. In fact, some cities like Boston and Baltimore, have actually reduced violent crime by stopping the prosecution of lower-level offenses, like nonviolent misdemeanors, which often make it hard for individuals to obtain a job or a loan due to criminal records, and can increase their likelihood of further criminal justice system involvement.

Importantly, the non-Florida cities in our sample have made significant strides in reducing violent crime through the kinds of “progressive” non-punitive approaches that DeSantis would call “soft-on-crime.” In Philadelphia, for instance, efforts to transform and clean vacant lots in high-poverty neighborhoods were associated with a 29% reduction in gun violence. Similar strategies are working in Chicago. And all four have “violence interrupter” programs, which have been associated with a 63% decrease in gun violence in the Bronx, and a 43% reduction in Richmond.

On the other hand, many of the “tough-on-crime” policies that DeSantis proposed in his criminal justice package—including permit-less carry and stronger penalties for drug crimes—are associated with higher violent crime rates and lasting reductions in social mobility for communities of color. So, when DeSantis argues that reducing crime requires punitive approaches over root-cause ones, it may be time to ask him what his tough-on-crime stance has done for Tampa, where violent crime rates are up nearly 40%.

When DeSantis compares “crime-ridden” cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia to his “safe” state of Florida, it is important to remember there is much more context, nuance, and evidence underlying the picture he’s painting. DeSantis’ flawed statements on crime and safety matter—not just for winning campaigns—but for ensuring the safety and well-being of all Florida residents.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

lois!!! you should listen to MF DOOM, he makes really good music and references a lot of cartoons

I have, I was listening to the mouse and the mask yesterday, Because it was one of Calebs favorite albums, I love the cartoon samples theres even a lois Griffin sample in the song El Chupa Nibre And thats what convinced me.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

IBR,NIBR and PNG Piping installations and erection In India

We have an extensive experience of executing underground and aboveground Piping projects involving Fabrication and Erection of IBR/ NIBR Pipelines in CS & SS, Process Piping for Chemical, Power, Cement, Mining, Pharmaceuticals and Steel Industry, including fabrication of Piperacks.

For more details please visit our website-

0 notes

Text

This reminds me of the Dangerdoom album in which Master Shake was constantly featured as well as the rest of the Aqua Teen Hunger Force lol. Maybe we can get another single/album but with the smiling friends in the future. Would be on theme ngl

happy smiling friends

#smiling friends#aqua teen hunger force#pim pimling#charlie dompler#master shake#rickchase art#Spotify

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Laguna Beach transitioning to FBI’s crime reporting system, officials warn numbers will look higher

Crimes occurring in Laguna Beach will be reported in greater detail offering more transparency following a switch to a national crime database, but that could also mean an increase in the numbers, city officials said. As of the new year, the Laguna Beach Police Department has started using the FBI’s National Incident-Based Reporting System, known as NIBRS, which puts the department in compliance…

0 notes

Text

I saw a post about the FBI tracking animal cruelty like homocides and arson. I looked into it, and this is true.

https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/-tracking-animal-cruelty

The post here seems to imply it values it as a warning sign to other crimes, but at the bottom it also states this quote:

"The National Sheriffs’ Association’s John Thompson urged people to shed the mindset that animal cruelty is a crime only against animals. “It’s a crime against society,” he said, urging all law enforcement agencies to participate in NIBRS. “By paying attention to [these crimes], we are benefiting all of society.”"

Hopefully with this, more animal cruelty will be stopped, and reports of it will get more attention. I think despite it being seen as "a warning sign to worse" that it is a step in the right direction of taking animal protection more seriously.

0 notes

Text

Harika nibr danışmanlık

https://www.sualpdanismanlik.com.tr/services/iso-belgeleri-ve-fiyatlari/

0 notes

Text

*2021 was the first year that the annual hate crimes statistics were reported entirely through the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). As a result of the shift to NIBRS-only data collection, law enforcement agency participation in submitting all crime statistics, including hate crimes, fell significantly from 2020 to 2021.

Case Examples

News

March 9, 2023

Mississippi Man Sentenced for Federal Hate Crime for Cross Burning

December 2, 2022

Mississippi Man Pleads Guilty to Federal Hate Crime for Cross Burning

September 23, 2022

Mississippi Man Charged with Federal Hate Crime for Cross Burning

December 6, 2021

Federal Officials Close Cold Case Re-Investigation of Murder of Emmett Till

September 30, 2021

FBI Launches Hate Crimes Awareness Campaign in Mississippi

November 5, 2019

Mississippi Man Sentenced to 36 Months for Crossburning

September 10, 2019

Mississippi Man Sentenced to 11 Years for Crossburning

August 6, 2019

Mississippi Man Pleads Guilty to Federal Hate Crime for Crossburning

April 12, 2019

Mississippi Man Pleads Guilty to Federal Hate Crime For Crossburning

November 26, 2018

U.S. Attorney Mike Hurst issued the following statement in response to nooses and hate signs found this morning outside the Mississippi State Capitol:

May 15, 2017

Mississippi Man Sentenced To 49 Years in Prison for Bias-Motivated Murder of Transgender Woman in Lucedale, Mississippi

#Mississippi hate crimes statistics#white hate#mississippi#white supremacy#hate crimes#crossburning#lynchings#racial violence#nooses require assistance always

0 notes