#NELA

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nela, Prague 2006, by Craig Morey

#Nela#craig morey#morey-art#b&w#b&w nude#b&w photography#artistic nude#moreystudio#black and white#fine art nude#nude art#signed prints available

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

#film#film photography#photography#photographers on tumblr#street photography#35mm#film camera#35mm film#color film#los angeles#35mmフィルム#35mmmagazine#los angeles street photography#los angeles blog#cinestill#NELA

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

I fight you 😈

*fight blocked*

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Korvex Skyline

#Nela#Nikita#lesbian#wlw#couple#acrador project#acrador#art#furry#my art#mindmachine#artists on tumblr#furry oc#furry character#commission#anthro#furries#anthro art#furry art#fursona

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

SHE'S AN ICON, SHE'S A LEGEND AND SHE IS THE MOMENT ✨

Marianela Nunez!!! One of my most favourite ballerinas! I adore the way she expresses and the joy and passion that shines from her. Such an inspiration 😭🤍

#nela#royal ballet#black swan#swan lake#kitri#don quixote#ballerina#marianela nunez#carlos acosta#pointe#royal ballet school#argentina

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

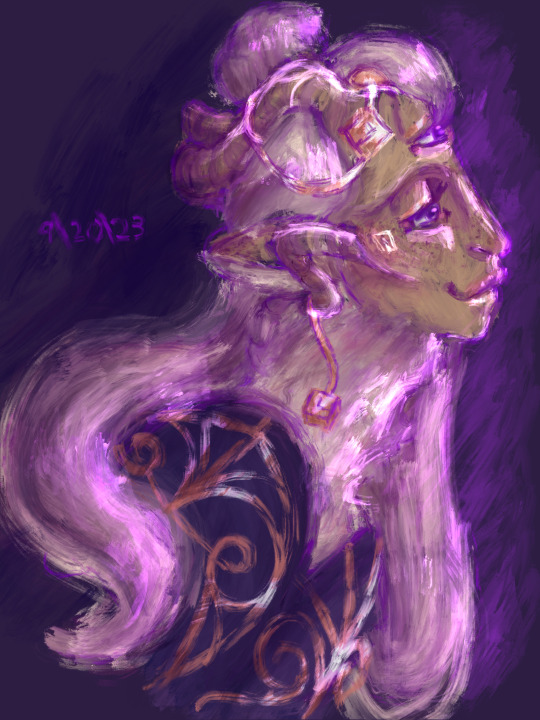

nela

#outer wilds#outer wilds oc#portrait#art by me#fanart#painting#nomai#outer wilds nomai#nela#hard lighting#purple#art#outer wilds fanart

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summerfest Day 6 - ABANDONED

It all goes wrong so quickly, and then, like every other job that gets dirty, Millie is trying as best she can to look away. There’s nowhere to bloody look, though – bloody is the problem. It’s on her sleeves. It’s in her mouth.

(They said it would be a clean one – they said –)

It had been going well, is the thing, they’d done everything right – Margaid went scouting, and Am-Tul sparked the base of a half-dead tree so it fell over the road, and Millie had triple-checked her bow and stocked her arrows and made sure everything was just right. Usually she’s just the lure, right, little girl in distress on the side of the road, please, sir, stop a minute – but ever since she turned thirteen that’s started to wear. The older she looks the more people will remember to be suspicious. And she’s well good enough to be doing shit properly, anyway, has been for years – she’s a better shot than any of the rest of them, and she’s okay enough with a knife if pushed, and she’s been getting kind of tired of being babied. She’s not a little kid anymore; she can do more than sit with her mum lying prone next to the road with a dagger hidden in her sleeve and cry. And Mum said it was time she pulled a bit more weight.

So it had been going well – the wagon stopped, and there were only three people, and one of them was a year or so younger than her so probably didn’t need much worrying about; she held her bow drawn and steady at him to keep the parents still, and when Dad plucked a half-eaten apple from one of their hands – fucking perfect – and held it aloft between index and thumb, just like they practised, she swivelled and loosed her arrow and had the next one drawn and nocked before the culls are done gasping. It nearly got knocked right out of his hand, juice dripping from the arrow-shaft shot into the core. That bit’s just showing off. But it works. It always works. Millie learned from her mum, and she’s got a bluff no-one ever wants to call. It had been going fine.

But then, over in the tangle of them, someone pressed something a little too hard, tones turned a little too ugly, and Millie had split her attention to keep an eye on it – her first fucking job on this end of things, she wasn’t having her mum turn it all thorny and difficult by running her fucking mouth, like she so often does with jobs that start out too easy – and then one of the wagon people yelled, and the kid freaked out, and –

He was stupid. He was so fucking stupid, because she hadn’t been properly focused, and he leapt at her like he thought he could knock the bow out of her hands, and she hadn’t been focusing because over there they’d started yelling so she flinched – and her fingers –

And he –

The bow’s on the ground somewhere, now, and Millie’s hands are on his chest, around the shaft of the arrow, her breath stuck thick as glue in her lungs, his breath leaking out from the hole she made in his, and he’s still – looking at her –

(The arrow landed with the same wet thump it does when Carilweth takes her hunting for cavies, and everything had gone quiet; then Mum had said, “Fuck,” at the same time one of the wagon people started screaming.)

When Millie’s acting lure her job is just to get people to stop, get them enough away from their stuff that they can’t reach it, and then she’s done; then there’s nothing left but to watch, or, when things take that turn, stop watching, close her ears, turn away. She’s turning away from what her parents are doing now, but it’s just towards something else; she can hear the steel clanging; she can taste blood. It’s not – she bit her tongue. It hurts. There’s blood on her hands, because she’s pushing down on the kid’s chest, around the shaft, blood on her sleeves where they trail – her fingernails are gleaming, sputtering like a burned-out candle, but his skin’s not doing anything, not closing – she’s not a good mage, never has been, can heal scrapes and bruises but that’s about it. Can’t begin to get the arrow out of him. It’s barbed. Even if she got the skin to close around it, veins mended, lungs sealed up, he’d still be fucked with the arrow still in him; she can’t even get it to close, and the harder she tries the faster the blood spurts, on her sleeves, on her fingers, spattered against her bowstring tattoos. Her throat hurts, a screaming pain, and it’s not until she realises that that she realises she’s talking – “I didn’t mean to,” she’s saying, hoarse, “I didn’t mean to, I didn’t mean to –” and he’s looking at her and not saying anything at all. Lips parted. He looks scared.

Then he stops looking scared and starts looking like nothing at all, and even her shitty healing won’t go anymore, but she’s still putting pressure on the chest. She stops talking.

The noise has stopped, across the road. If she was still playing lure, it would mean it’s time to open her eyes again.

Footsteps. Squelching, a bit. This stretch of road runs too close to a swampy bit coming off the Niben; sometimes wheels get stuck in it and they don’t even have to do anything. A vague shadow falls over her, drowning out the faint dappling from between the leaves.

Millie says, dry-mouthed, “I didn’t mean to.”

“You can let go of him,” says her mum. Her voice is what, for her, very nearly passes as soft. It doesn’t help. It feels worse, actually.

Millie says, “I didn’t mean – he started at me and I – my hand slipped –”

“Mills,” Mum says, “he’s dead. You don’t have to keep pressure on it.”

“I didn’t mean to kill him,” Millie says, and she’s shouting, a bit.

Something presses at her shoulder. Carilweth is offering her a canteen. She shoves it away. She doesn’t move her hands. There’s still blood on them. It’s stopped gushing. They’re all standing around, and there’s more bodies on the road she hasn’t looked at, and there have been bodies on the road before, and she doesn’t –

It’s different, when she’s got her hands around the shaft of the arrow, covered in blood.

It was supposed to be a clean job.

Dad puts a hand on her head, rough-palmed on her hair, stubby fingers brushing her forehead. She butts it off. “Don’t.”

Mum says, “Come on, Mills. Take it easy,” and Millie looks up at her, at all of them; still crouched over a corpse with her hands around the arrow, staring. They all look tired. They’re all looking at her. Margaid, hair frizzy and loose round her head, mouth twisted in something approaching sympathy; Am-Tul, tail curled; Carilweth, face pinched; Dad, glancing over at the horses, still lashed to the cart.

Millie swallows and repeats, “I didn’t mean to.”

“I know,” Mum says, like she really does, and lays a heavy hand on her shoulder. And then, “We talked about how important it is to stay focused.”

(And it’s guilt that you feel, isn’t it, when you’ve killed someone without any good reason and you didn’t mean to; that’s how that feels, Millie knows, and so she knows that’s how she’s feeling, even if she doesn’t feel much of anything nameable. That’s what makes sense. The feeling she gets next is so vivid she doesn’t even need to think about it – rage, like in all her dog-eared Pelinal books, white-hot and spitting and like, for a moment, she could eat them all alive.)

She lashes out, flailing, violent, and her forearm hits her mum’s knee; her hand streaks blood on her trousers. It’s a shit hit. Most times Mum would drag her up and tell her to do it better, but right now Mum can eat a dick.

“You were distracting me! You were fucking yelling and keying everyone up, like you always do!” Millie hits her again, hard as she can, her form no better the second time. One hand’s still on the boy. On the body. “I was keeping an eye in case shit went sideways, like you told me! You were fucking me up!”

Mum steps neatly back out of arms’ range, her mouth twisting but not ticking like it does when she’s really mad; Carilweth says quietly, “You said you’d take it easy on the kid, Nela.”

She jerks her head, sharp, derisive; the gold in her ears glisters in the dappled sunlight. The boy’s blood shines half-dried on the cloth at her knee. “She’s well old enough to make a bit of balsam,” she says, voice tart; “I was out on the pad at her age.”

Margaid snorts. (She’s cleaning off her fucking knife. Millie is going to – she’s cleaning off her knife. She’s laughing.) “You’d knapped at her age, you weren’t doing shit,” she says, and Am-Tul is looking over at the other side of the road like he’s planning disposal, and Dad’s looking at the fucking horses, and Millie’s had it.

“I fucking killed someone!” she says; bashes her bloody hand into the ground, dirt gumming to the heel of her palm, and she says it again, loud and raw enough to scrape, to make her throat hurt, until they all shut up and pay attention. “I killed someone, I killed someone, I fucking killed someone! Why didn’t you do anything?”

“Should have caught your arrow, should I?” says Mum, voice acrid, a strand of hair loose over her eye.

“Nelly,” Dad says.

Millie snaps, “Go fuck yourself.”

“No, tell me how this is my fault,” Mum says; she gestures, short and sharp, at the whole circle of them, towering over her. “How this is any of our faults. You fucked up, Mills – you want to cry about it, whatever, but don’t try to pin it on me.”

Millie’s voice is cracking when she says, “If you weren’t showing off –”

“You’re not a colt,” Mum replies flatly. “You know how this works.”

“Nelly, she’s upset,” says Dad, soft-voiced; “she’s not going to listen now.”

The body’s still just there, on the ground, eyes open, mouth slack. And Millie isn’t a colt. She does know how this works. She’s not new to scamping, and she’s not new to violence; can’t count how many fucking times she’s seen a job go south and come to this. But she’s the youngest, and she was always the lure, and before now she’s always been able to look away. It’s another thing when you’re looking it in the face. It’s another thing when you did it and it’s your fault. It’s different. It’s new. She doesn’t like it.

And she can’t look away.

Mum’s looking at her, mouth twisted, close enough both to sympathy and irritation to get confusing. “Look,” she says, gruff. “Your first milling business, that’s rough. I get that. But it was going to happen sometime. Maybe best to get it out of the way.”

There’s blood sticky and covered with dirt on her hands. The boy is on the ground. They haven’t even closed his mouth.

“You don’t even care,” Millie says, and she fixes her eyes on the place where the wood of the arrow-shaft meets torn cloth and too much blood, which she really didn’t want to look at before but feels rather like nothing, now. The bleeding’s stopped. It’s all over. It’s all over. Rough, she says, “Leave me alone.”

“You going to clean up here on your own?” Mum asks, slanted, and Millie just kind of shuts her ears off after that. There’s a bit more conversation. She waits for it to be done. She waits for them to go away. Carilweth crouches down to kiss the top of her head, first; the ridges of Am-Tul’s tail brush against her back. Dad takes the horses’ reins. Good fucking riddance.

The boy’s not bleeding anymore, because he’s dead. His eyes are open. He has freckles. She’s never felt good about looking away, exactly, but it was just routine; but all hell, she doesn’t know how they kept doing it if it felt like this every damned time.

“Come on back to camp when you’re feeling a bit better,” says Dad; and he doesn’t apologise. None of them have ever apologised. She wants it, suddenly, worse than she’s ever wanted anything, and it’s about as practical as hoping she might sprout wings and fly off into the sky. Fuck. She wants to hit someone again. She wants it to be this morning again and for everything to go different. She wants to be five years old and for everything to be like it used to. It’s not the same. It can’t ever be the same.

She waits for them to be gone; watching the faint dappled sunlight shifting over her blood-soaked hands, listening to the faint complaining of frogs, the high-pitched sawing of cicadas. Somewhere, there is a bird. She doesn’t know its name, but she knows its warbling call. She hates it, right now.

When it’s just her and the frogs and the cicadas and the bird that won’t shut up and the corpse, she walks forward a little on her knees and grabs him around the armpits. Leaves the bow where it is in the dirt. Begins to drag him out, to where the ground gets swampier, to where, a short few minutes’ walk away, there’s the marshy bank of the river. Not one of the off-shoots, twisting twigs and branches, but the Niben proper. She’s never been to a funeral – she’s only ever really known five people, and none of them are dead – but she’s read about them. There’s no priests of Arkay out in the back-ends of Blackwood, the stretches of swamp-road between towns, and she doesn’t have a shovel, but underwater is close enough to underground, and the river-spirits from the really old stories can make up for the consecrations.

They can say all the rites and whatever too, if that’s important, because Millie sure as hell isn’t.

She almost trips over one of the other corpses as she passes it; kicks its arm out of the way. The back of its hand is flushed red.

A body’s an unwieldy thing to carry, it turns out; Millie drops the boy in the mud twice. His clothes get stained. There’s spatters of dirt on his skin, which is cold. He was nearly as tall as she was, standing up, so there’s a fair bit to manage, and his limbs flop all over, unsteady. It’s like dragging a coil of rope, the ends going everywhere. He leaves a trail in the mud. That feels like exactly what you don’t want when you’re hiding a body. But she’s not trying to hide, and she can’t heave him up any higher. She can hear the lapping of the river.

She drops him at the bank; stands over, looking at him. Eyes open, mouth open, arrow-shaft still sticking out of his chest. Bloody. Cold. His blood is still on her hands; so first, she kneels down in the muck, and she washes them as best she can without soap in the sluggish-running water, watching red bloom like rust in its surface. Sunlight glances off the surface of the river. The water is cooler than outside, but not cold. She rubs off what she can, watching it run clean, and employs her bitten-down fingernails for the gummy bits; scratches long, red marks parallel to her veins, running criss-cross over her palms, picking at the skin around her nails. The water is dirty. There’s no soap. That’s probably why it still doesn’t feel clean.

She closes the boy’s eyes. Her fingers are wet, wrinkled; water dribbles down his face, like he’s been crying, which he hasn’t, because he’s dead. She closes his mouth. It falls open again. His skin feels like normal skin. There’s mud on his cheek. She almost just rolls him into the water like that, but it doesn’t feel right – his face uncovered – his arms all floppy, like octopus limbs. There’s no coffins here. If she had her scarf she could manage a shroud, but it’s a warm day; she didn’t wear it.

There’s pale red running down her hands again. The damp end of her sleeves are still wet with blood.

Better than nothing, she decides, so she peels off her tunic, picks an arrow out of her hip quiver, sits down in the mud, and starts slicing through the thread at the seams. It’s not easy, with the point of the arrowhead. Takes fucking forever. Half the fabric is wet with sweat. Her skin feels clammy. She feels a little bit insane, but also the most rational she’s ever been.

(She’ll need another tunic – a change of clothes or two, if she can grab them, which means a bag. A canteen, for water. Some lightweight food. She’ll have to leave most of her books. Most everything. She can get new books. She can get new everything. Jewellery, though, good to keep – easy to carry, easy to hide, easy to sell – so she’ll need all of hers, and, fuck, some of everyone else’s into the bargain, why not. Mum has gold enough. Margaid has a few pieces somewhere. Am-Tul has the horn rings. And Dad never wears any of his, so he wouldn’t even notice. A bow, because she’s not going back to the road to get hers. A knife, something that can be a tool and a weapon in a pinch. And cash. As much as she can carry. Talk about making a bit of balsam.)

(Everyone will be back at camp, now, the one with the broken wagon. They probably wouldn’t all leave to do the cleaning, but figuring out the horses and the wagon in the road would be a job and a half; if she’s lucky, they’ll all be gone to manage it by the time she makes her way back. At least most of them. Millie doesn’t want to talk to anyone. She doesn’t have to. She’d like to see them try and make her.)

(In and out, like housebreaking, that year they stayed in Leyawiin. Pack a bag and be gone. There’s other roads in the world. If she’s old enough to kill someone she’s old enough to find them.)

Her hand slips, nearly at the end of the side-seam; the arrowhead slips and carves a neat groove in the meat of her palm. Blood wells up, red as rubies, staining the creases.

Millie looks at it, for a moment; then she puts the fabric down, and she leans out over the water, and she retches. Only twice. Nothing comes up. Her mouth tastes sour.

(She has to leave, and she has to do it now, because nothing will ever really be the same but if she stays it will get back to being close, and it will be like it didn’t matter. And it did matter. And none of them cared.)

She rips the last few stitches in the seam; they tear easy as grass. The boy is as unwieldy as he was before as she tries her best to swaddle him in it. The sleeves are dangling. Fabric is fraying. His jaw still won’t close, so she snaps the head off the arrow with a bit of her blood on it and puts it over his mouth, the point facing down. The rest of the fabric she puts over his face.

She looks at the cloth-clad lump of him for a moment. She does not apologise. She doesn’t think she knows how.

She doesn’t say anything. There’s nothing to say.

When she pushes him into the water – past the mud of the bank, into the current of it – he sinks, silent, under the sunlit oil-slick of the surface. The cut in her hand is dribbling into the river. The sky above is bluer than anything else in the world.

(Camilla Patesca will disappear that day. She will never be seen again.)

#every time I reread this I say 'why did I do that.' and I say 'sorry'. but I don't change it to be less miserable because I love it#I love going into backstory stuff. I loveee creating a guy and then reverse-engineering why they're like that#finally getting around to figuring out the yellow road highwaymen going Wow... explains a lot#no wonder they're like that#this takes place about a year before the oblivion main quest :)#tesfest24#oc tag#pax#and. for good measure#nela#silaus#am-tul#carilweth#margaid#the elder scrolls#tesblr#oblivion#tes#fay writes#my writing

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

some pixels of my wotr characters i made like a yr ago

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bom dia, já pensando nela.. 🙃

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Tuesday

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nela, Prague 2006, by Craig Morey

#Nela#craig morey#morey-art.com#fine art nude#b&w nude#b&w photography#artistic nude#moreystudio#black and white#signed prints available

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

A MEETING OF THE MINDS -- WHAM! BAM! POW!

PIC INFO: Spotlight on living legends Jim Lee, comic book artist, writer, publisher supreme & Serj Tankian frontman of SYSTEM OF A DOWN (as well as activist, artist, and now writer), photographed at his one man multimedia exhibition “Lost Technique” @ the Eye for Sound hybrid cafe/art gallery, 1638 Colorado Blvd., Eagle Rock, CA, c. late September 2024.

Source: www.picuki.com/media/3446499074206254179.

#Jim Lee#Serj Tankian#SYSTEM OF A DOWN#Alternative Metal#Nu Metal#Jim Lee Artist#WildStorm Productions#Lost Technique#SOAD#DC Universe#Comic Book Artist#90s Marvel#Serj Tankian Lost Technique#Jim Lee 2024#Serj Tankian 2024#Art Gallery#Eagle Rock#Los Angeles#Eagle Rock California#Vocalist#Multimedia Art#Multimedia Artist#DC Comics#Northeast L.A.#L.A.#American Style#Writer#NELA#Comic Books#Eye for Sound Gallery

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joey Quinones.

#film#film photography#photography#photographers on tumblr#35mm#film camera#35mm film#street photography#los angeles#north east los angeles#NELA#aes#img#b&w film#bnw#blackandwhitephotography#black and white film#los angeles street photography#los angeles blog#los angeles photography#35mmフィルム#35mmfilm#35mm camera#35mm photography#Spotify

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bikes on the spider bridge, April 2024

#los angeles#california#photography#google pixel#tybg#fyp#photos#my photos#pictures of la#fixie#bikes#cyclist of tumblr#bikes of tumblr#fixed gear bike#roadbike#bmx#gravel bike#frogtown#NELA#LA#la river

6 notes

·

View notes