#My LSE Journey

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My life is perfect in all aspects

Over the past year, every aspect of my life has improved—financially, socially, emotionally, and even in small daily joys. I’ve built a life that is stable, abundant, fulfilling, and full of ease. Below is a breakdown of how each area of my life has transformed.

1. Financial Stability & Abundance

At the start of this journey, I was in a constant state of financial stress. My rent was ridiculously high, I was terrified of spending money, and I felt restricted in what I could afford. Now, I’ve reached a state of financial abundance where I no longer feel worried about money:

✔ Rent reduced from £710 to £360, saving me hundreds every month.

✔ Income increased significantly—earning £95–£120 per day, providing stability.

✔ Extra £2,300 discovered in October, removing the stress of saving for the PSW visa.

✔ No longer feel guilty spending money—I buy what I want, when I want.

✔ Commuting costs reduced by £30–£40 per day due to moving closer to work.

✔ Mom got a job in February, so we no longer have to send her £300 monthly.

✔ Can now afford to go to any café for coffee whenever I want, which was unthinkable before.

Biggest Shift: I no longer live in scarcity. I trust that I always have more than enough.

2. Lifestyle & Living Situation

My living environment went from being restrictive and expensive to comfortable, affordable, and fully mine:

✔ Moved into a perfect room that feels like home.

✔ Finally have free laundry access, saving money and making life easier.

✔ Invested in my space—bought a rack, bookshelf, and TV, making my room more functional and cozy.

✔ No longer have to stress about my accommodation or move again.

Biggest Shift: I finally feel settled and comfortable in my living space.

3. Social Life & Friendships

I went from feeling alone and isolated in the UK to having meaningful connections and deep friendships:

✔ Steph became my best friend in the UK, and we spent so much time together.

✔ She even invited me over for Christmas, making my holiday warm and special.

✔ No longer feel lonely during important moments—I now have a strong support system.

Biggest Shift: I went from spending holidays alone and crying to being surrounded by love and friendship.

4. Small Daily Joys & Indulgences

A major transformation has been my ability to enjoy life without guilt:

✔ Started ordering food more often, no longer feeling guilty about spending.

✔ Bought self-care items like scented sticks, a facial mask, and a scrub—things I used to restrict myself from.

✔ Got back into K-dramas, movies, and celebrity crushes (Cha Eun Woo!), adding fun and excitement to my days.

✔ Started cooking delicious Chinese noodles at home, a new skill and joy.

✔ Began going to cafés freely after realizing I didn’t have to stress about money anymore.

✔ Cinema trips became a regular part of my life, sometimes even for free.

Biggest Shift: I now allow myself to enjoy life freely instead of living in restriction.

5. Career Growth & Future Security

My work life has completely stabilized, and I now feel secure in my future:

✔ Consistent work booked until the end of the year, providing financial stability.

✔ Likely to transition into an easier class soon, making work even more manageable.

✔ Learned that PR/sponsorship is easier than I thought—only need a £24K salary, which is achievable.

✔ Discovered LSE is now the #1 university in the UK, increasing the value of my degree.

Biggest Shift: I no longer feel uncertain or anxious about my future—everything is working in my favor.

6. Mental Peace, Stability & Self-Concept

Perhaps the biggest shift has been in how I see myself and how I experience life:

✔ I have fully detached from stress, fear, and desperation.

✔ My self-concept is stronger than ever—I feel like the chosen one.

✔ I know that everything always works out for me, and I no longer doubt it.

✔ I have reached a state of peace and neutrality, trusting that my desires will manifest.

Biggest Shift: I no longer chase or force outcomes—I trust that things are unfolding perfectly.

7. Travel, New Experiences & Memorable Moments

This year also brought incredible trips and experiences:

✔ Went to Harvard—a huge milestone, proving how much I am achieving.

✔ Spent Christmas in London at Steph’s house, instead of being alone.

Biggest Shift: I am experiencing new, exciting things, making life feel richer and more fulfilling.

Final Summary: Everything Has Improved

Every aspect of my life has transformed for the better:

✔ Financially → More income, less stress, freedom to spend.

✔ Living situation → A comfortable, affordable home that truly feels like mine.

✔ Social life → Deep friendships, no more holiday loneliness.

✔ Small joys → Buying what I want, indulging in self-care, enjoying hobbies again.

✔ Career security → Stable work, sponsorship confirmed, future secured.

✔ Mental peace → Detachment, confidence, ease—knowing everything works out for me.

✔ New experiences → Harvard, Christmas in London, embracing new opportunities.

If this much has changed in just a few months, I can only imagine how much better things will get. My life is now filled with ease, joy, and abundance, and I know that everything will continue to unfold in my favor.

0 notes

Text

Well done, you!

An LSE Journey Essay

Looking deep into ourselves to find our real motivation can be hard especially when everything around us have been going by in a blur. Our true purpose, should we ever find it early, tend to get lost somewhere between making a living, paying the bills, raising kids and running a hundred different errands. Before you know it, you're well into your middle age and wondering where did the last 10 years go. It is in this age that I started to question what my endgame is.

I was born in the North to Ilocano parents, raised in Metro Manila and educated in both private and government institutions. I majored in Architecture but majority of my work is in another discipline. For the past 13+ years in Singapore, I worked, and mostly enjoyed, working in Civil Engineering specifically in Geotech where we do a lot of underground works for tunnels and transport structures. Such a badass feeling for a female to actually do this in a predominantly male field! I left the Philippines not because there was a pressing need to provide. On the contrary, I have a stable but boring job in the city. I was surprised when I got the call from a foreign headhunter that, at the prospect of new adventures and since there's nothing to lose (they paid for all the expenses anyway), I relented and went along to see where'd I'd end up. Fortunately, fate has been good.

Being a migrant worker for most of my youth can be quite unsettling. I have all the time in the world in a new environment full of possibilities, earning a decent disposable income and not saddled with pressing responsibilities. When you're new in a foreign land, the allure of all things shiny are very tempting. It's these times that I went on a spree, a moderate one by standard, but to an Ilocano it's a spree nonetheless. Year in and out, I accumulated stuff that I liked and like to share with my family. But as my belongings grew and lugging them from one rental house to the next becomes harder, I thought "there must be more to gain in living here than this".

Enter social media.

I spent numerous hours scrolling, clicking and just wasting time away but it's an upside that I saw an A-LSE sponsored seminar on one of the shared posts. At this point I'm already indoctrinated in the concept of financial management by another OFW (also an admirable Fin-Lit and Social Enterprise advocate) and seeing the A-LSE program page with all the bright faces of the students, my curiosity was piqued. What is this group that makes people come together and learn new stuff to improve themselves? The FOMO (fear of missing out) is strong and I had to join in on the fun. I finally got in a year after putting my name down on the waiting list.

And so, the grind begins.

The program started with self-introspection -- who are you, what makes you get up in the morning, what's your mission -- its wading at the rubbish and finding the bits that radiate sunshine. It's the equivalent of doing the Marie-Kondo in your life and removing the clutter.

As a parent, my goal is to give my child the tools and opportunities that will enable him to achieve good things in life. Not great, but good. I can only lead him to the starting line, I will leave it up to him to finish it in ways he sees fit. Of course, to be able to do that I will need the financial capacity to provide for his primary needs but also to be there emotionally to support and guide him in his decisions. My goal is to show him the dignity in working and the joy of doing good, to impart the values I've learned from my parents, to have fun and appreciate the arts.

As a sibling, my goal to help them finish their tertiary education has been fulfilled. My siblings are now enjoying their chosen professions and has now embarked on new pursuits to ascend to the next level. Next is to help them map out their financial plans for the future -- that's a tactic to make them financially independent and not borrow money from me.

As a daughter, my goal is to see my parents enjoy the latter years of their lives and to help them come into terms that they need to step back and let their children take on the responsibilities on managing their estate.

As a person, my goal to become an instrument of change in however small way I can manage. Running for public office seems the easiest route but as I have no death wish and plan to live a longer-ish life, that's a no-go for me.

My goal is to achieve financial independence in the next decade, to establish my own enterprise, have enough to sustain my health coverage and retirement in the later years and leave a worthy legacy to my family. Lastly, I want to travel every year or every other year to places that are culturally rich and ‘gram worthy.

The 10 sessions have brought immense knowledge and insight about the core competencies of the LSE program. Journals have been written to provide a deeper insight for each session.

For Leadership, I find Tina Liamson's lecture on Migration & Principles of Leadership enlightening. The most fascinating has got to be from Dr. Juan Kanapi's Appreciative Inquiry. This is the first time I've heard of it and it's quite difficult to grasp the idea and can be easily confused with positivity. But at the end, It shows that if practiced AI is not just mind tricks but a powerful tool in realising your full potential.

The best lectures for Financial Literacy are the split sessions of Vince Rapisura and Edwin Salonga. (Edwin's lecture is about Social Entrepreneur but I remembered a lot more on his lecture about Finances, hence…) Who knew studying finance concepts could be this good? And most definitely not boring! I now have a deeper understanding about managing my finances better and learning that my current insurance is shit, which I really need to rectify soon. I can't tell you enough how the things I've learned from these wonder duos are gold. Call me by any other name (read: biased), but Ed's lecture is my most favourite of the lot.

The Social Entrepreneurship sessions have the most gravitas for these lectures carry the main core of the program. They're not all boring, mind you, but can be a bit challenging. The lectures on this series provided many useful tips for future entrepreneurial endeavors and is a big help in formulating our business plan. Other insights for the SE series can be read here and here.

At every journal writing, I try to reflect on what I've learned and think of ways to apply them in my daily life. Most often I find things and events that need to be tweaked or heavily redesigned in order for it to be aligned with my future goals. Most pressing of these are the consolidation of my assets and liabilities, and making a clear plan on mapping out my finances that will include my son's future education. The next point is to work on myself and how I carry myself as a leader starting at home. What better place to practice than to apply these learning in the household first? Hopefully, I will be able to improve my inability to forge meaningful connections to people by the time I have to build my own enterprise. I am not aspiring to be Miss Friendship, I'm ok with Miss Effective Boss or even Miss Influencer-For-The-Greater-Good. Tall order, I know, but we're allowed to dream and dreaming is free.

Joining the program made me realise the answer to my question, "So what happens now?"

During my first few years as a migrant worker, my goal is to save so I can buy gadgets to connect me home. After having a mobile phone, a laptop and the ability to call home any time, ano na? As I enter my 14th year of being a migrant, I've somewhat been able to achieve the things I hoped for. Not the millions of dollars in bank account **fingers crossed**, but a comfortable life. But that restlessness persists. Learning that there are available avenues to pursue these in the Philippines is a big help in making me step into the right direction closer to the things I wanted to become. Programs like these give hope. With that, I realise that there is more I can do back home than where I am currently at. I have the knowledge; I can share it -- starting with a small group of like-minded people who are willing to help themselves. Acquiring and sharing knowledge is free so I may as well start with that.

All the sessions have been audio recorded and kept in a cloud that I shared with family members. Many of the things Dr. Kanapi said are the things I so want to say to my father. Sharing it is just a click away, let him hear it straight from the board-certified horse's mouth.

I also plan to lead the residents in our small sitio towards a better understanding of financial management which can be instrumental in their livelihood. These people have been known in the family for decades. They have worked alongside our grandparents in tilling the land and their children continues to do so. While there have been advancements in their lives, I believe there is more to be done -- better education for their children/grandchildren, opening bank accounts, accessing government programs, using tech etc. I am excited to share with them the different concepts we have learned in the program, and also a good training ground for me to improve my leadership skills.

I highly commend the A-LSE program for striving to make the Filipino Migrant Workers' quest for relevancy and better lives. Much appreciation to A-LSE founding Team and the current secretariat who makes it run smoothly. The past month has been very trying but everyone has been great in providing feedback and extending their hands. For that, a big Salute! to everyone -- for the team and the speakers who traverse the globe every year.

As a program alumnus, I will most definitely uphold the values of the LSE in the best way that I possibly can. Sadly, my physical involvement with the LSE will not extend to the volunteer work for the next batch as I have made plans for the next year that will make it impossible to fulfill my duties on the site . However, I am willing to extend my skill/expertise in whatever way I can as long as it is done remotely.

Thank you, A-LSE.

Congratulations, Batch 83!

2019 will be remembered as the year I turned another leaf over.

0 notes

Text

My Psychedelic Journey

Why take mushrooms?

What do they do to you?

I want to explain why I take them, my reasoning is not for everyone if anyone else at all! We all have our reasons.

So, Since being 16 i have taken drugs, started on pills, then coke and onwards. I had a coke & speed addiction for a 2-3 year period and often relapsing. I had consciously not taken psychedelics as i have known I've been mentally ill since being 20 and being diagnosed and given Prozac at that age. I was wary that i would have bad trips or i would be stuck on a trip. I just felt the risks were too high, especially taking medication and all the other drugs. Pretty sure i took LSD one night at a party was these green things and i was off my nut, i was in a different reality and i was quite honestly scared. i went skinny dipping in November at Great Yarmouth beach! So yeah it was a weird thing to happen and to this day can't remember what these pills/little plastic-looking things were or what i did with them, literally can't remember if it was paper or a pill. they were just in a bowl with all the other drugs.

I digress, several years later, I’d been clean maybe 1-2 years of all substances including weed, well maybe the odd joint but we moved somewhere we couldn't find a supplier! So we would have to make a 2-hour drive down to manchester just to pick up but eventually decided it wasn't worth the money in fuel. We were also skint which didn't help matters. We eventually found a supplier of weed and met new people who like us, liked drugs. We started sessioning on anything and everything. Mainly research chemicals as they were cheap and plentiful. m-kat hadn’t be criminalised at that point so we were importing large amounts of it. My friend, Xander decided to start making his own drugs. We were all sceptical about it but we trusted him. He made LSE(?) which is pretty much LSD but i think weaker, that trip was a nightmare as i spoke to my boyfriend just before the trip and i hadn't hung up and he heard me slagging him off...Anyway, moving on lol He made DMT one day, took ages. We had enough for the 3 of us who wanted to do it and my god, it's a short trip but it changed my way of thinking forever. I may revisit the DMT experience later. We did DMT a fair few times before i abruptly moved out as i ended the relationship with my boyfriend.

Now i did some research online, it wasn't as fruitful in results as it is today, we are talking 10 or so years ago. So came across mushrooms and some scant info on where to find them and how to take them. I went for a walk with the dogs, we lived in the middle of nowhere, 1500 ft above sea level (lived on top of hartside) and by a river and lots of sheep. Anyway, i started looking in sheep fields and soon realised that the fields were full of them! I would collect enough for a few doses at a time and dry as much as possible. I was taking shrooms 3-4 times a week including at times DMT.

So we’ve got to where i am taking them, i best explain why and what the effects were.

To be honest i took it as an escape. My relationship was a nightmare, he made me feel like death was my only escape. I had spoken to friends who had used psychedelics and they thought it might help me feel better. I had started being in pain a lot too at that point but not medicated for it. I was still taking meds but when planning i stopped taking them the day before. As Psilocybin is affected by SNRI’s. That applies to most drugs though tbh. it gives you a very high tolerance, you have to take more to feel it. Which could result in serotonin syndrome.

I wanted to search deeper inside myself, i had been interested in Buddhism and Krishna consciousness for maybe a year at that point and i saw it as a way of speaking to god. to confirm to myself that he existed. What i got was a revelation.

So using it so regularly means i can't remember each trip but i can give you what i learned and saw from those experiences.

I would take maybe 10g (its rough but 6 cup teapot with a handful of shrooms in) of fresh shrooms in tea. Tasted rank but get it down you! Then wait, and it is a waiting game!

I would sit cross-legged, often by the log burner, just close my eyes, listen to music and i would feel calm. A completely blissed feeling. An inner peace. I could see patterns and colours, swirling great vortex’s of colours and light. If i opened my eyes the patterns and colours overlayed the room and i would just forget i was in the room. I would see parts of my past, like showing me it wasn't my fault, that i should let go of trauma. I saw my present and it was like looking at my brain, black, covered in clouds and dying. If i touched it then there was a flash of colour. I saw the energy of the universe in front of me, glowing and pulsating in front of me, my heart beating with it, a feeling of supreme power came over me like i had been recharged. I was seeing my future, i saw the love i am capable of giving and receiving. It showed that my empathy wasn't a weakness and showed i was a good soul, It made me think deeply on experiences and learning from them, it cleansed me, it rewrote who i was. All hate drained from me. At peace with myself and others. The visuals were amazing, you can't describe it, you cant show the colours on a palette, you cant imagine the scale of this place. It truly was an amazing thing to do with my life for a year.

So it showed me a different me and overtime i morphed into that person. Today i am still hugely empathetic towards people. I have a kind and calm nature. I don't hold onto hate & i respect myself more.

However, i have decided i need to revisit the energy, i need its healing and recharging. I want to journey further and this time i get to do it with someone i love, my sister. She’s used drugs infrequently for a few years but like me, she has mental problems and wants to try shrooms more holistically than just ‘getting high’ and she thinks i can do that with her. I will be there to look after her, to experience everything with her. I want her to get to where i did and she sees life differently. That she grows as a person. It will be a very special journey that i get to be a part of.

So we reach the end of my epic. I hope you read it and enjoyed it. Maybe learn something, understand it better, i don’t know but most of all it's out there. Sharing experiences are a solid way of learning and getting to know someone.

Enjoy your mushrooms, be safe & enjoy your trip <3

youtube

#pyschedelic#pyschadelic#psychedelia#shrooms#mushrooms#magic mushrooms#magic truffles#getting high#breaking through#tripping#drugs#high on drugs#growing as a person#god#energy#mushroom picking#liberty caps#psilocybin#shpongle#hang drum

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Analysis: Song Mingi, the ‘Wind Whisperer’

Languages: English, Japanese (Post Transformation), Korean (Modern Day), French (Modern Day), Spanish, Sign Language (ESL, JSL, KSL, LSL, LSE-Modern Day)

Crew Position: Boatswain

Powers: Aerokinesis/Air (Inherited from Japanese God, Fujin)

Compass Position + Arrowpoint Stone: South Eastern, located under his collarbone, Crystal Opal

Eye Color: Brown (Natural)/ Violet (Demonic Form)

Hair Color: Brunette (Natural)/ Crimson (Demonic Form)

Piercings: Prince Albert (Modern Day)

Likes: Praise, Successful Snatches, Orange Juice, Crafting Presents for Friends and Family, Reading Stories With the Crew

Dislikes: Bella Rose, Manipulative People, Mean-Spirited People, Being Left Alone

*The above image of Demonic Mingi is a commissioned piece from @seonghwea and is not to be taken out of this moodboard. Reposting isn’t cute, if I find this piece anywhere besides on Atlas’ blog and here in this moodboard, we WILL file a dmca. Don’t be an asshole :)

Mingi.

An unfortunate child, with a heart of gold. Raised amongst a poor band of thieves, but still finding a family worth more than even the finest diamonds. A child raised around the honey and warmth of a found family.

Until the day poison began to seep into his life in the form of a little girl with a wicked smile.

Not even the smiles of his precious baby sister can stave off the looming force of negativity known as Bella Rose.

Boatswain Song Mingi.

The sails fly high above the heads of the members of the formidable Utopia. Reliable, sturdy, innocent, and strong. Despite his inexperience, the crew looks towards him for guidance on affairs regarding cargo and other crew members.

A loyal and hard worker, none of the crew members are opposed to following behind their boatswain. They sing a hearty shanty together, passing barrels to and fro under his leadership.

Something about orange juice, but no one seems to mind too much, as long as their boatswain keeps that smile on his face.

-Mythology-

Feared and respected are the brothers of the storm. The lightning, Raijin, and the wind, Fujin.

Fujin, an unruly force of nature, is often depicted with messy, wind swept curls and an intimidating snarl. Upon his back is a bag of winds, which is the source of his power. He rides upon a nimbus cloud and can devastate the lands below just as easily as he can aid humanity.

For all of the lost life that comes from typhoons, at times, the wind is on the side of Fujin’s people. Such a case would be an instance in the 1200s, when the invading Mongol fleet was devastated by a horrible wind storm. Sometimes, the helpful storm is attributed to Fujin’s divine intervention.

From a gentle summer breeze to a volatile tornado, Fujin is the god behind it all.

-Power Applications/Demon Transformation-

Upon fully using his powers, Mingi’s hair bleeds into a deep crimson color. His eyes shift into a dark violet tone and a shining, glittering cloud-like mark appears on his cheek. The mark glitters in the light, and the more Mingi uses his powers, the more you can see the hues of color within the gem swirl around within the mark.

Despite being a Boatswain, not a Navigator or Sailing Master, Mingi still uses his powers for the crew’s ocean exploration. Alongside Hongjoong pushing Utopia with strong waves, Mingi puts the wind in her sails, speeding up their journey and cutting their trips down to over half the time it would take for them to sail places.

The force of Mingi’s wind can change, from a light breeze to vicious typhoon or tornado force winds. Though he is one of the more combative of the men when it comes to using his powers, Mingi doesn’t have a particularly organized style of fighting.

What he lacks combative style, he makes up for it in sheer force and power. Mingi plays strong offensive support in group fights and will use his winds to either push or pull enemies closer to the others. Out of the eight of them, sans Hongjoong, Mingi has the farthest reach with his powers.

He is also one of the mobile members, using the force of his winds to fly through the air and close the distance on long-range enemies. His powers work better when there is some space between them, as it does take a bit for him to muster up the winds for them to be useful in attacks. If he’s interrupted when gathering the winds-specifically before a wind storm-he’ll have to start all over again, but if he manages to stop one, him summoning more or being attacked won’t detract away from the first initial storm.

Ideally, Mingi fights better with an even, level field to fight on, as too many obstacles on a battlefield will break some of the force of the winds and lessen the damage he can cause. Mingi may not be a trained fighter like Seonghwa, Jongho, or Yunho, but he knows how to use his size to his advantage, and can hold his own fairly well in a hand to hand fight.

-Character Song Breakdown-

All of the main boys have a song assigned to them in the AtT playlist to go alongside their origin chapters. Mingi’s character song is Never Be Like You by Crywolf. He also has another song that strongly relates to him so I’ll share some lyrics from the other song as well, Masochist by Matt Van.

Both songs feal with Mingi’s near suffocating anxiety and his loss of self-worth as a result of Bella Rose’s constant torment.

‘What I would do to take away this fear of being loved

Allegiance to the pain

Now I'm fucked up and I'm missing you

I swear she'll never be like you

I would give anything to change this fickle-minded heart

That loves fake shiny things

Now I'm fucked up and I'm missing you

I swear she'll never be like you’

Originally this song is intended to be for a man pleading for forgiveness from an ex-lover, but I decided to use the hurt from the lyrics to change the meaning to apply to Mingi. His fear of being loved, stemming from Bella’s verbal and emotional abuse, is something we follow throughout his time with the pirates aboard the utopia.

Mingi was raised to be a pickpocket, and that ties in for his love for ‘fake shiny things’. While with the crew and battling with himself, Mingi has to convince himself to accept the good feelings he receives from the others around him and how they’ll never be like Bella Rose. She, though deceased at the time of him joining the crew, will never be like them, either.

‘Stop looking at me with those eyes

Like I could disappear and you wouldn't care why

Now I'm fucked up and I'm missing you’

Throughout their time together, Bella Rose makes it abundantly clear she only ‘cares’ for Mingi during the times she needs or wants his aid for something. Mingi also has issues making and keeping eye contact from time to time, as a result of his trauma.

‘I'm only human. Can't you see?

I made, I made a mistake

Please just look me in my face

Tell me everything's okay

I'm only human. Can't you see?’

To wrap this up, I’ll share some lines from Masochist that share the same sentiment and message as the song we’ve just gone over.

‘As long as I'm not myself

I think I'll be safe, yeah

What am I looking for

In this state between love and war

Am I chasing a chemical

That just leaves me wanting more

And is there a difference

Between truth and happiness

If ignorance is bliss

To the emotional masochist’

‘We can go pretty far

If you wanted

'Cause I know it's not your thing

To stay in one place, yeah

I can be what you want

I can be anything

As long as I'm not in love

I think I'll be safe’

-Character Blurb-

“Slowly.”

“I can’t-”

“If you say you can’t one more time, I’ll tell Yeosang to never give you any oranges ever again.”

Mingi sat up straighter, frowning as he looked down at the paper in his hands. Seonghwa sat across from him. His long legs crossed as he watched Mingi. It was his turn to tutor the boatswain for the week and Mingi felt small under his steel gaze. With a shaky breath, he scanned the paper.

“Read it.”

“I am, I swear-”

“Aloud.”

Mingi pursed his lips, startling when Seonghwa crossed the room, leaning into his space. Mingi shied away, but Seonghwa followed, catching his chin between his fingers. He tilted his head and smiled, and Mingi felt his heart stutter.

“You can do it, and I promise it’ll be worth it when you do. Read it, please.”

Mingi blushed and smiled as Seonghwa placed an encouraging kiss to his nose before pulling him away, giving him some space.

“O-one cup…” he squinted at the page before perking. He knew that word. He’d seen it before in the galley while working with Yeosang.

“Sugar! It’s sugar!” Seonghwa smiled from beside him, carding long fingers through tousled brunette hair before nodding.

“Excellent.” He placed a rewarding kiss on his lips. “Continue.”

One by one, Mingi slowly read the list of things on the paper, each time encouraged by Seonghwa’s gentle purred praises or a small compliment in that accent they all loved so much.

Milk. Cinnamon. Nutmeg. Vanilla. Coconut.

When he finished, he tilted his head, blinking.

“Is...this a recipe?”

Seonghwa’s lips quirked before he nodded.

“It sure is, meu amado. Yeosang picked up a book on Caribbean desserts at the last port and he wanted to make you something. Toto, I believe it was?”

Mingi’s eyes lit up as he perked, looking at Seonghwa like an overgrown puppy. If he squinted, the ex prince could swear he could see a tail wagging back there. He chuckled and kissed him, nodding towards the door.

“Let’s get you something to eat to celebrate.” he hummed. Mingi nodded and took off like a shot, smiling ear to ear as he raced down to the galley, joy erupting in his chest at the scent of vanilla and coconut that flooded the inside of the ship.

He’s never felt so at home.

-M.List-

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Big Names on Campus Part 1 - Your Sabbatical Officers

Coming to LSE can be daunting, and we know that you guys may be feeling understandably nervous. One thing that will definitely help you is finding out as much information as you can – that way, you can be as well-informed as you can and jump right into life at LSE!

Speaking of important information…have you heard about your Sabbatical Officers? Your Students’ Union is run by 5 full time sabbatical officers and 12 part time officers. They were elected by the rest of the student body last year, and they are the ones who decide what we do for the next academic year. In other words, they basically call the shots here at LSESU.

For all of you guys, they are very important people to know for two main reasons: No. 1 – they are the ones who can actually DO something about a problem you could be having at LSE, so raise any concerns to them! No. 2 – your sabbatical officers have done the whole student experience from start to finish, so they have a wealth of advice and tips to offer.

So here we go, this is your part 1 of the Big Names on Campus – a quick introduction to your Sabbatical Officers:

David Gordon, Your General Secretary

Pronouns: He/Him Instagram: @david_gordon24 Facebook: David Gordon Email: [email protected] “Hey everyone! I have no doubt that you are all excited about joining us at LSE. I’m your General Secretary (AKA President) for the next academic year 2020-2021 and served as your Community & Welfare officer last year. LSE has such a diverse and vibrant community, and I can’t wait to meet you all!

I’m a graduate of BSc Philosophy, Logic & Scientific Method and lived in Carr-Saunders hall in my first year, where I was the Vice-President of the hall’s committee. During my studies, I was a part of the LSESU Men’s Rugby Club and the LSESU Mixed Lacrosse Club, which was fantastic - I loved being part of both clubs, being able to play the sports, to get stuck into the social side that comes with being a part of the Athletics Union, as well as the opportunities to focus on and challenge sports culture at LSE. There was also a lot of activism and campaigning which was great to support and be a part of. Making sure LSE is a safe and welcoming place for everyone is our top priority as officers, with plenty of opportunities to get involved.

Here are the top 2 things that I think you should do in your first year:

Get involved. Whether you want to take part in a new sport, or join a society, make sure you try new things and explore what LSE has to offer. If a new class mate invites you to an event, whether its online or in person, try it out. The best thing about LSE is the people, so connecting with people through the SU and your department is one of the most rewarding things you can do.

Come and say hi to us, your Sabbatical Officers! Our job is to represent you full time, we are here to support you in your time at LSE by lobbying for change and empowering you with opportunities. If you think there’s something we could to do help, don’t hesitate to get in touch!

One service that I think you should really familiarise yourselves with is the LSESU Advice Service. They can help you with a range of issues or can signpost you to the relevant services who can offer further support. The truth is, we can all have problems at LSE, but the important thing is that you use the support services available to you if you need them. Even if you just need to talk it out with someone, go and speak to the Advice Team.

My general advice for all you new students would be to take it at your own pace. I know how quickly everything can go during Welcome and that you are presented with a whirlwind of information; especially as we head into a new and unfamiliar kind of learning environment. And while you’re trying to make the most of this new and exciting experience, remember just to take it easy. And no matter what you want to get out of LSE, there will be people who want the same thing - so go out there, find them and do it together!”

Ellie Duplock, Your Activities & Development Officer

Pronouns: She/Her Instagram: ellie_activitiesdevelopment Email: [email protected]

“Hey everyone! My name is Ellie and I’m going to be your Activities & Development Officer for the upcoming year. I hope you are excited to start your LSE journey!

I’ve just graduated from LSE with a degree in International Social & Public Policy. I lived in Bankside Halls as well as in Camden and Holloway during my time here. Sports played a big part in me LSE experience. I was the Vice Captain of the AU Waterpolo Womens’ Team in my second year, then was a member of the Athletics Union (AU) Executive Team and AU Boxing Secretary in my third year, as well as playing in the fifth team of AU Netball! Taking part in the AU Fight Night in my second year and then running the event in my third year were the highlights of my time at university!

My favourite thing about LSE is probably the location – it’s right in the heart of the city! I'm from North East London originally, but living in central meant I did a lot more exploring this year, and it helped me make the most of being at a university. We’re so lucky that LSE is in such a good location.

The top 2 things I think new students should this year:

Join a club or society – definitely one of the best ways to make the most of your university experience!

Make the most of your contact time / office hours. Starting classes can feel a little overwhelming at first, but your class teachers and lecturers will always be happy to help.

For me, the most important service that I think students should be aware of is the Students’ Union (LSESU)! When I was a student, I didn't really make the most of the support and guidance they offer until I became part of the Athletics Union Executive Team in my third year. The LSE Volunteering Centre is also fantastic and I wish I'd looked more into that when I was a student!

In terms of my priorities for the year, you should definitely keep an eye out for the Visual Art Showcase that I’m planning, in conjunction with the LSESU Creative Network! It aims to highlight the incredible creative work that our students do. There’s lots of other projects in the works right now that I’ll be sharing details of through the year, with potential for one really big change for LSESU aswell, so watch out for these!”

Bali Birch-Lee, Your Education Officer

Pronouns: They/Them Twitter: @theotherbali Email: [email protected]

“Hello! I hope you are all looking forward to your arrival in September. I’m Bali and I’ll be your Education Officer for the upcoming year. I studied an MSc in Political Sociology here at LSE and actually did my undergraduate degree over at Cambridge, where I studied Education.

I didn’t live in halls, I rented privately with my partner, a 45-minute bus ride from campus. This worked really well for me as it allowed me to keep a distance between my work and chill spaces, plus it gave me a lot of time to read on the bus!

I wasn’t part of any clubs or societies during my Postgraduate study here at LSE, but I did perform in one of the “LSE Chill night” music events and sang with the Philosophy and Logic department band…not sure how this managed to slide seeing as I wasn’t actually a student of their department, but hey ho!

My favourite thing about LSE is the wide array of people you get to meet! It’s such a diverse place. I think there are 2 very important things all new students need to do in their first year:

Find out how you learn best! LSE can be quite a different experience to school or work environments – or even previous universities. Take some time to work out how you want to organise your time and which learning approaches work best for you.

Seek out those interesting discussions! Challenge people, bounce your thoughts off one-another and explore the topics that really tickle your curiosity. If there is someone in a class with you who you have a bit of an academic crush on, talk to them! So much learning and processing can happen in the conversations that you strike up outside of the classrooms.

In my opinion, The LSESU Advice Service is the most important service to know about! I didn’t really understand what it was until I became a Sabbatical Officer and I wish I had taken the time to find out when I was a Postgrad. They do such incredible work supporting students, providing help and guidance whatever issue a student may be facing.

I’m working on a lot of priorities this year, but I would definitely say that our work on Diversification and Decolonisation of the Curriculum is something to watch out for. I’m really looking forward to working to make the curriculum more inclusive! We are looking to holding talks and events to provide extra-curricular opportunities to engage with more diverse and radical topics, as well as addressing courses and departments. If you’re interested, then definitely keep an eye out for ways you can get involved!”

Laura Goddard, Your Community & Welfare Officer

Pronouns: She/Her Instagram: @laura_communitywelfare Email: [email protected]

“Hi guys! I’m Laura, your Community & Welfare Officer for 2020-2021. Congratulations on securing your place at LSE, I can’t wait to welcome you to LSE in a few weeks time!

I initially started doing a Politics and International Relations here at LSE, but at the end of my first year decided to switch to a straight International Relations course. I’ve just graduated, I lived in Connaught Hall which is an intercollegiate hall right on Tavistock Square – I definitely took for granted the 15/20 min walk onto campus! Personally, I loved my living experience and I got to meet people from KCL and UCL as well as LSE.

When studying, joining AU Mixed Lacrosse club was probably the best decision I made. It was a super sociable club and I learned a new sport completely from scratch. I went on to join the Mixed Lacrosse committee in second year and became club captain in my third!

My favourite thing about LSE, as cliché as it sounds, is the people. Everyone you meet has such impressive life experience and that’s so inspiring for your own future and goals. It’s a really motivating environment to be in!

The top 2 things I think you should do are:

Find a society or sports club that feels right for you – it’s not just about playing the sport, you will form a really strong and tight knit community with other members. They were like a second family to me!

Consider volunteering with the LSE Volunteer Centre – your first year will be a whirlwind, but making time to give back is so important. It also has amazing benefits in terms of your mental health and wellbeing.

I echo what my fellow Sabbatical officers have said - the most important service that I think you need to know about is without a doubt the LSESU Advice Service. You can get free, impartial advice on any issue that you may be facing while you are at LSE, with advisors who are incredibly understanding and have been trained in dealing with a wide range of issues.

This year I am focusing on improving all students’ experience of LSE’s mental health services and sexual violence support because to me; nothing is more important than the wellbeing and the support services available for you at LSE, and they need to reflect the diversity of its student body. I’ll be updating you on the progress of this throughout the year, stay tuned!”

Your Sabbatical Officers work full time for LSE Students’ Union to represent your views and negotiate with the School to improve your student experience. If you have an issue, want to raise a concern or feel like a change needs to happen at LSE – these are the people who can do something about it. They are open to your suggestions and feedback, and welcome your insights on how they can improve your experience at LSE. You can reach out to David, Ellie, Bali and Laura on their respective emails.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Settling In

The first month of my LLM journey was so busy and eventful that until now I’ve hardly had time to reflect on it. Adjusting to my new life as LSE student has been a little overwhelming, but very exciting: registering for the program, choosing modules, meeting fellow students from all over the world during welcome events and many more.

Prior to my arrival in London, I had doubts as to whether it’s a good place for a student as opposed to small university towns with slower life pace. But despite being situated in the city centre, right next to the Royal Courts of Justice, LSE campus has a very peaceful vibe which makes you forget that you are in one of the busiest world capitals. Plus, I feel very lucky to be living in a student hall within 5 minutes walking distance from LSE, and also very close to Covent Garden and the theatre district.

Due to the fact that the LLM program is very international, with students from different backgrounds, during the welcome week we had introductory lectures about the English legal system and EU law. Also, I found very helpful postgraduate law option fairs that were designed to help students decide which modules to choose for the year ahead. In essence, each professor did a short presentation of his/her module(s), and after that took questions from the audience.

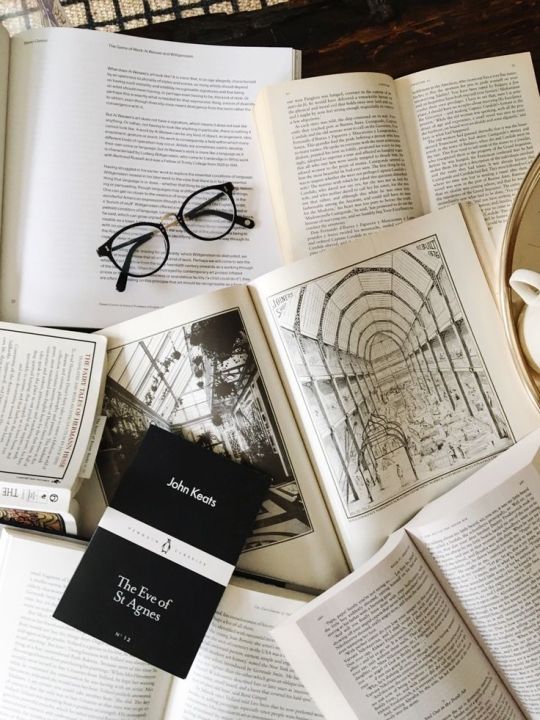

At LSE you are expected to complete a total of eight courses, one of which is compulsory for everyone - Legal Research and Writing Skills. The latter will be assessed by a master dissertation to be submitted by the end of summer. What I found peculiar is that you can write your dissertation on any legal topic irrespective of your chosen modules. However, if you wish to focus on a particular area of law and have a specialism to your LLM, your dissertation topic has to fall within it.

Also, each student on the LLM is assigned an academic mentor from the law department who you can turn to for advice. Basically, your mentor keeps track of your academic performance and general wellbeing throughout your time at LSE and regularly contacts you to arrange meetings. Interestingly, your mentor is often specialised in a different area of law than the one you choose to specialise in at LSE, however, it doesn't preclude them from giving you valuable advice on course choice and other aspects of your academic life.

One of the highlights of my first weeks at LSE was a welcome reception at the Law Society on Chancery Lane - home to professional body of solicitors in England and Wales. Despite the fancy setting, it was a great opportunity to socialise with law department professors in a rather informal way and commemorate the start of this exciting new life as LLM students at LSE.

Coming from an education system where the relationship between students and their professors is supposed to be very formal, I find it helpful to be able to approach your teachers and talk to them outside classroom.

The weather in London is infamously gloomy (mostly) this time of the year, which makes it easier to stay in the library and study for long periods of time without being distracted. But if you do get tired, there is always the option of lying on the beanbag beach :)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

"Window into the World: I have an endless curiosity about our world. I want to explore its natural wonder, meet its people and listen to their stories, and travel to far flung places. This is my education" - Blaise Buma The Open Dreams Family Celebrates the success of its co-founder, Blaise Buma who continues to set the pace in the quest for quality and befitting education. Blaise just graduated from the Havard Business School, which is consistently ranked among the top business schools in the world. From Government Bilingual High School Bamenda (GBHS Bamenda) - Cameroon to Washington and Lee University in the USA to The London School of Economics and Political Science - LSE in the UK and Tsinghua University in Beijing, China (Schwarzman Scholars) and now havard university in the USA, Blaise indeed is a scholar par excellence and has conquered the world. And it's not over yet! The number of scholars following a similar path like him is rising geometrically within the Open Dreams. Here are his notes on this achievement: "Not to make a mountain out of a molehill, this achievement is for every student in my community who aspires to attend institutions like the Harvard Business School, HBS. If I set out on this journey today like I did many years ago in Bamenda, I may never have the chance to attend an institution like HBS. In our forgotten war, students all across the Anglophone Regions of Cameroon are out of school due to a protracted conflict that has exacted an incalculable toll in our community. This achievement is also for them. But in the face of adversity, there is plenty of room for hope. Many organizations, like Open Dreams, that didn’t exist when I graduated from high school now make it easier so more students have a decent shot at attending institutions like Harvard. And hopefully in the future, we won’t have to leave home to get a good education abroad. For now it’s time to celebrate. Tomorrow, it’s back on the road to continue to find new ways to use my education to serve my community." You may visit blaisebuma.com/about/ to read more about his convictions. #HALIAccessNetwork #SDG4QualityEducation U.S. Embassy Yaounde UK in Cameroon #intlacac https://www.instagram.com/p/CeJOojUOts0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Idea Development

Reviewing and reflecting my idea

Catterall, Pippa. 2020. On statues and history: The dialogue between past and present in public space. LSE.

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/statues-past-and-present/#:~:text=treated%20as%20sacrosanct.-,They%20represent%20what%20people%20in%20the%20Past%20chose%20to%20celebrate,to%20represent%20power%20and%20authority.I

When I was reviewing my initial images from my first assessment and conceptualizing how editing them could alter the context of them, I began to realise that my original context was not capturing the essence of what I wanted. How someone identifies with their culture is a very personal one and can be very raw and emotional.

The earlier notion of adding movement some somehow symbolise the spiritual side just was not working as it took the focus away from my subjects and almost cheapened their feelings.

I found myself therefore contemplating relationships themselves and how it can make people feel when they feel seperated from their culture and the embarrassement it can cause and I realised the feeling is that of being broken inside and out. I had considered photoshopping the movement but this was to distracting and too obvious. I also thought about editing the images so that one or both the subjects just faded away, but this did not have the impact I was after either.

A concept that started to develop in my head was that of statues and how they could develop and deepen the context of my work. When I was researching what statues represent I came across a statement that impacted me and that was that ‘They represent what people in the Past chose to celebrate and memorialise, they do not represent history.’ When I applied this reasoning to my work, I realised that this is definitely the avenue I wanted to go down as in my case and for my images.

People’s identity journeys do not necessarily have to be representative of the history of the culture, it’s an individual journey and someone standing firm (like a statue) and stating “I am Maori��� ... “I am Tongan”.... “I am Samoan”.... I am Cook Island”.

0 notes

Text

When Fred Halliday—scholar, activist, journalist and teacher—died two years ago at the too-early age of 64, obituaries and tributes swamped the British press; the New Statesman subtitled its remembrance “The death of a great internationalist.” Halliday was a truly original thinker, a combination of Hannah Arendt (in her concern for the connection between ethics and politics) and Isaac Deutscher (in his materialist yet supple approach to history). Halliday also knew a little something about the Middle East: he spoke Arabic, Farsi and at least seven other languages, and he traveled widely throughout the region, including in Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Palestine, Israel, Libya and Algeria. He is one of the very few writers who, after 9/11, understood the synthesis between fighting radical Islam and opposing the brutal inequities of the neoliberal global order. He was an uncategorizable independent, supporting, for instance, the communist government in Afghanistan and the US invasion of that country. He embodied the dialectic between utopianism and realism. In his scholarship and research, in his outspokenness and courtesy, in the complexity of his thinking, he was the model of a public intellectual. It is Halliday’s writings—not those of Noam Chomsky, Edward Said, Alexander Cockburn, Christopher Hitchens or Tariq Ali—that can elucidate the meaning of today’s most virulent conflicts; it is Halliday who represented radicalism with a human face. It says something sad, and discouraging, about intellectual life in our country that Halliday’s death—which is to say, his work—was ignored not only by mainstream publications like The New York Times but by their left-wing alternatives too (including this one).

It is cheering, then, that a selection of essays, written by Halliday for the website openDemocracy between 2004 and 2009, has just been published by Yale University Press. Called Political Journeys, it gives a taste—though only that—of the extraordinary range of Halliday’s interests; included here are analyses of communism , the cold war, Iran’s revolution, post-Saddam Iraq, violence and politics, radical Islam, the legacies of 1968 and feminism. The book gives a sense, too, of Halliday’s dry humor—he loved to recount irreverent political jokes from the countries he had visited—and his affection for lists, as in the essay “The World’s Twelve Worst Ideas” (No. 2: “The only thing ‘they’ understand is force”). But most of the articles, written as they were for the Internet, are comparatively short and represent a brief span in a long career; this necessarily sporadic volume will, one hopes, lead readers to some of Halliday’s two dozen other books and more extensive essays.

Political Journeys is a well-chosen title for the collection. It alludes not just to Halliday’s travels but also to the ways his ideas—especially about revolution, imperialism and human rights—changed in reaction to tumultuous world events over the course of four decades. For this he has often been attacked, even posthumously. Earlier this year, Columbia University professor Joseph Massad opened a piece about Syria, published on the Al Jazeera website, by dismissing Halliday—along with his “Arab turncoat comrades”—as a “pro-imperial apologist.” (Massad also put forth the novel idea that Syria “has been…an agent of US imperialism,” which might be news to Bashar al-Assad and the leaders of Iran and Hezbollah, Syria’s allies in the so-called axis of resistance.) Yet it was precisely Halliday’s intellectual flexibility—his ability to derive theory from experience rather than shoehorn the latter into the former—that was one of his greatest strengths. Pace Massad,

Halliday didn’t move from Marxism into imperialism, neoconservatism, neoliberalism or “turncoatism”; rather, he developed a deeper, more humane and far sturdier kind of radicalism. It was one that refused to hide—much less celebrate—repression, carnage and virulent nationalism behind the banner of progress, world revolution, selfdetermination or anti-colonialism. Halliday sought not to reject the socialist tradition but to reconnect it to its heritage—derived from the Enlightenment, from 1789, from 1848— of reason, rights, secularism and freedom. He would also develop an unsparing critique of the anti-humanism that, he thought, was ineradicably embedded in the revolution of 1917 and its successors.

Halliday believed that the duty of committed intellectuals is to keep their eyes open, to learn from history, to be humble enough to be surprised (and to admit being wrong). The alternative was what he called “Rip van Winkle socialism.” He sometimes told his friends, “At my funeral the one thing no one must ever say is that ‘Comrade Halliday never wavered, never changed his mind.’”

* * *

Fred Halliday was born in 1946 in Dublin and raised in Dundalk, a town near the northern border that, he pointed out, The Rough Guide to Ireland advises tourists to avoid. The Irish “question” and Irish politics remained, for him, a touchstone—though more as a warning than an inspiration, especially when it came to Mideast politics. The unhappy lessons of Ireland, he wrote in 1996, included “the illusions and delusions of nationalism” and “the corrosive myths of deliverance through purely military struggle.” He added: “A good dose of contemporary Irish history makes one sceptical about much of the rhetoric that issues from dominant and dominated alike.… [A] critique of imperialism needs at the very least to be matched by some reserve about most of the strategies proclaimed for overcoming it.” Growing up in the midst of the Troubles, Halliday developed, among other things, a healthy aversion to histrionic nationalism and the repugnant concept of “progressive atrocities.”

Halliday graduated from Oxford in 1967 and then attended the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Later he would earn a PhD from the London School of Economics (LSE), where, for over two decades, he taught students from around the world and was a founder of its Centre for the Study of Human Rights. (The intellectual and governing classes of the Middle East are sprinkled with his graduates.) He was an early editor of the radical newspaper Black Dwarf and, from 1969 to 1983, a member of the editorial board of the New Left Review, a journal for which he occasionally wrote even after he broke with it over key political issues. He immersed himself in the revolutionary movements of his time and gathered an enviable range of friends, interlocutors and contacts along the way: traveling with Maoist Dhofari rebels in Oman; working at a student camp in Cuba; visiting Nasser’s Egypt, Ben Bella’s Algeria, Palestinian guerrillas in Jordan and Marxist Ethiopia and South Yemen (the subject of his dissertation). He wasn’t shy: he proposed a two-state solution to Ghassan Kanafani of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, infamous for its hijackings; argued with Iran’s foreign minister about the goals of an Islamic revolution; told Hezbollah’s Sheik Naim Qassem that the group’s use of Koranic verses denouncing Jews was racist—“a point,” Halliday dryly noted, “he evidently did not accept.”

Halliday received, and accepted, invitations to lecture in some of the Middle East’s most repressive countries, including Ahmadinejad’s Iran, Qaddafi’s Libya and Saddam’s Iraq, where a government official told him, without shame or embarrassment, that Amnesty International’s reports on the regime’s tortures and executions were correct. Clearly, he was no boycotter. But neither was he seduced by these visits: in 1990, he described Iraq as a “ferocious dictatorship, marked by terror and coercion unparalleled within the Arab world”; in 2009, he reported that the supposedly new, rehabilitated Libya was just like the old, outcast Libya: a “grotesque entity” and “protection racket” that was regarded as a joke throughout the Arab world. His moral compass remained intact: that year, he warned the LSE not to accept a £ 1.5 million donation from the so-called Charitable and Development Foundation of the dictator’s son, Saif el-Qaddafi. Alas, greed trumped principle, and Halliday’s arguments were rejected—which led, once the Arab Spring reached Libya, to the LSE’s public disgrace and the resignation of its director.

* * *

In May 1981, Halliday published an article on Israel and Palestine in MERIP Reports, a well-respected Washington journal that focuses on the Middle East and is closely identified with the Palestinian cause. It is an astonishing piece, especially in the context of its era, more than a decade before the Palestine Liberation Organization recognized Israel’s right to exist and the signing of the Oslo Accords. It is no exaggeration to say that, at the time, the vast majority of the left, Marxist and not, held anti-Israel positions of various degrees of ferocity; to do otherwise was to risk pariahdom.

While harshly critical of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and of the occupation , Halliday proceeded to question—and forcefully rebuke—the bedrock beliefs of the left: that Israel was a colonial state comparable to South Africa; that Israelis were not a nation and had no right to self-determination; that Israel was a recently formed and therefore inauthentic country (most states in the Middle East—including, for that matter, Palestine— are modern creations of imperialist powers); that a binational state was desired by either Israelis or Palestinians and, therefore, could be a recipe for anything other than civil war and a harshly authoritarian government. (Halliday asked a question often ignored by revolutionaries: Why would anyone want to live under such a regime?)

Most of all, he challenged the irredentism of the Palestinian movement and its supporters. Partition, he presciently warned, is “the only just and the only practical way forward for the Palestinians. They will continue to pay a terrible price, verging on national annihilation, if they prefer to adopt easier but in fact less realizable substitutes, and if their allies and supposed friends continue to urge such a course upon them.” Halliday stressed that a truly revolutionary strategy cannot be “at variance with reality.” Solidarity without realism is a form of betrayal.

The reality principle, and its absence, was a theme Halliday would return to frequently, as in his reappraisal of the legacy of 1968. “It does not deserve the sneering, partisan dismissal,” he wrote in 2008. But nostalgic celebration was also unearned, for “the problem is that in many ways, we lost.” Despite triumphal rhetoric, the year of the barricades led not to worldwide revolution but to conservative governments in France, England and the United States (Richard Nixon). In the communist world, the situation was even worse: “It was not the emancipatory imagination but the cold calculation of party and state that was ‘seizing power.’” In Prague, socialist reform was crushed; in Beijing, the Cultural Revolution’s frenzy reached new heights.

Yet Halliday, like most of us, was sometimes guilty of letting wishful thinking cloud his vision too. In 2004, he called for the United Nations to assume authority in Iraq, which was then in free fall. This ignored the fact that Al Qaeda’s shocking bombings of the UN’s Baghdad mission the previous year—resulting in the death of Sergio de Mello, the secretary general’s special representative in Iraq, and so many others—had disposed, rather definitively, of that issue; the UN had withdrawn its staffers and, clearly, could not ask them to undertake another death mission. (Nor was there any indication that the UN’s member nations—many of whom opposed any intervention in Iraq—would have supported such a proposition.) And his claim, made in 2007, that “a set of common values is indeed shared across the world,” including a commitment to “democracy and human rights,” is hard to square with much of Halliday’s own reporting—such as his 1984 encounter with a longtime acquaintance named Muhammad, who had formerly been a member of the Iranian left. Now a supporter of the regime, Muhammad visits Halliday in London and explains, “We don’t give a damn for the United Nations.… We don’t give a damn for that bloody organisation, Amnesty International. We don’t give a damn what anyone in the world thinks.… We have made an Islamic Revolution and we are going to stick to it, even if it means a third world war.… We want none of the damn democracy of the West, or the socalled freedoms of the East.… You must understand the culture of martyrdom in our country.” Indeed, Halliday’s optimism of the intellect here is belied by even a casual look at any of the world’s major newspapers— whether from New York or Paris, Baghdad or Beirut—on any given day.

* * *

Iran, which Halliday first visited in the 1960s as an undergraduate, was foundational to his political development; he analyzed, and re-analyzed, its revolution many times, as if it was a wound that could not stop hurting. (Iran is the only country to which Political Journeys devotes an entire section of essays.) His initial study of the country, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, was written just before the anti-Shah revolution of early 1979. Based on careful observation and research, the book scrupulously analyzed Iran’s class structure, economy, armed forces, government, opposition movements, foreign policy—everything, that is, but the role of religion, which Halliday seemed to regard as essentially a front for political demands, and which he vastly underestimated. The book’s last sentence reads, “It is quite possible that before too long the Iranian people will chase the Pahlavi dictator and his associates from power… and build a prosperous and socialist Iran.”

Events moved quickly. In August 1979, Halliday filed two terrifying dispatches from Tehran, published in the New Statesman, documenting the chaotic atmosphere of fear and xenophobia, the outlawing of newspapers and political parties, and the brutal crackdown on women, intellectuals, liberals, leftists and secularists. “It does not take one long to sense the ferocious right-wing Islamist fervour that grips much of Iran today,” he began. Later, he would write, “I have stood on the streets of Tehran and seen tens of thousands of people…shouting, ‘Marg bar liberalizm’ (‘Death to liberalism’). It was not a happy sight; among other things, they meant me.” A revolution, he realized, could be genuinely anti-imperialist and genuinely reactionary.

But the problem wasn’t only Iran or radical Islam. As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, it became clear—or should have—that most of the third world’s secular revolutions and coups (in Algeria, Syria, Libya, Ethiopia and, especially, Iraq) had failed to fulfill their emancipatory promises. Each became a one-party dictatorship based on repression, torture and murder; each stifled its citizens politically, intellectually, artistically, even sexually; each remained mired in inequality and underdevelopment. None of this could be explained, much less justified, by the legacy of colonialism or the crimes of imperialism, real as those are. These were among the central issues that led to Halliday’s rift with the New Left Review—and that continue to divide the left, both here and abroad. Indeed, it is precisely these issues that often underlie (and sometimes determine) the debates over humanitarian intervention, the meaning of solidarity, the US role as a global power, the centrality of human rights and of feminism, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. (In 2006, Halliday would sum up his points of contention with his former comrades, especially their support of death squads and jihadists in the Iraq War : “The position of the New Left Review is that the future of humanity lies in the back streets of Fallujah.”)

Halliday’s revised thinking—his emphasis on democracy and rights; his aversion to the particularist claims of tribe, nation, religion or identity politics; his unapologetic secularism; his questioning of imperialism as a purely regressive force—is evident in his enormously compelling book Islam and the Myth of Confrontation, published in 1996. (Halliday dedicated it to the memory of four Iranian friends, whom he lauded as “opponents of religiously sanctioned dictatorship.”) In this volume he took on two still prevalent, and still contested, concepts: the idea of human rights as a Western imposition on the third world, and the theory of “Orientalism.”

Halliday argued that, despite the assertions of covenants such as the 1981 Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights (which defines “God alone” as “the Source of all human rights”) and the 1990 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (which defines “all human beings” as “Allah’s subjects”), there is no such thing as Islamic human rights—or, indeed, of rights derived from any religious source. Such rights apply to everyone and, therefore, must be based on man-made, universalist principles or they are nothing: it is the “equality of humanity,” not the equality before God, that they assert. (That is why they are human rights.) Because rights are grounded in the dignity of the individual, not in any transcendent or divine authority, they can be neither granted nor rescinded by religious authorities, and no country, culture or region can claim exemption from them by appealing to holy texts, a history of oppression, revered traditions or because rights “somehow embody ‘Western’ prejudice and hegemony.”

In this light, the search for a kinder, gentler version of Islam—or, for that matter, of any religion—as the basis of rights is “doomed” to failure; for Halliday, the question of a religion’s content was entirely irrelevant. “Secularism is no guarantee of liberty or the protection of rights, as the very secular totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century have shown,” he argued. “However, it remains a precondition, because it enables the rights of the individual to be invoked against authority.… The central issue is not, therefore, one of finding some more liberal, or compatible, interpretation of Islamic thinking, but of removing the discussion of rights from the claims of religion itself.… It is this issue above all which those committed to a liberal interpretation of Islam seek to avoid.” The issues that Halliday raised in 1996 are by no means settled today, and they are anything but abstract; on the contrary, the Arab uprisings have forced them insistently to the fore. In Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, secularists and Islamists struggle over the role (if any) of Islam in writing new constitutions and legal codes; at the United Nations, new leaders such as Egypt’s Mohamed Morsi and Yemen’s Abed Rabbu Mansour Hadi argue that the right to free speech ends when it “blasphemes” against Islamic beliefs.

But more than a defense of secularism is at stake here. Halliday argued that the very idea of a unitary, reliably oppressive behemoth called the West—on which so much antiimperialist and “dependency” theory rested— was false. “Far from there having been, or being, a monolithic, imperialist and racist ‘West’ that produced human rights discourse, the ‘West’ itself is in several ways a diverse, conflictual entity,” he wrote. “The notion of human rights was not the creation of the states and ruling elites of France, the USA, or any other Western power, but emerged with the rise of social movements and associate ideologies that contested these states and elites.” The West embodied emancipation and oppression, equality and racism, abolitionism and slavery, universalism and colonialism. Political theories and practices that refuse to acknowledge this—proudly brandishing their “anti-Western” credentials—will be based on the shakiest foundations.

* * *

The argument between advocates of the concept of “Orientalism,” put forth most famously by Edward Said, and its critics—often associated with the scholar Bernard Lewis—was close to Halliday. Lewis had been a mentor of his at SOAS, and one he admired; Said, whom Halliday described as “a man of exemplary intellectual and political courage,” was a friend. (Though not forever: Said stopped talking to Halliday when the two disagreed on the first Gulf War.) Yet on closer look, Lewis and Said shared an orientation: both had rejected a materialist analysis of Arab (and colonial) history and politics in favor of a metadebate about literature. “For neither of them,” Halliday argued, “does the analysis of what actually happens in these societies, as distinct from what people say and write about them…come first.” Increasingly, Halliday would regard the Orientalist debate as one that deformed, and diverted, the discipline of Mideast studies and helped to foster a vituperative atmosphere.

Said had argued that, for several centuries, British and French writers, statesmen and others had created a static, mythical Middle East—sometimes romanticized, sometimes denigrated, always objectified— as part of an unwaveringly racist, imperialist project. (Indeed, Said’s book has turned the word “Orientalist,” which used to refer to scholars of the Muslim, Arab and Asian worlds, into a term of opprobrium.) With sobriety and respect, Halliday considered and, in the end, devastatingly refuted the theory’s major tenets. With its sweeping, all-encompassing claims, he argued, the concept of Orientalism was a form of fundamentalism: “We should be cautious about any critique which identifies such a widespread and pervasive single error at the core of a range of literature.” It was based on a widely held yet entirely unsubstantiated belief that Europe bore a particular hostility toward the Muslim world: “The thesis of some enduring, transhistorical hostility to the orient, the Arabs, the Islamic world, is a myth.” It was undialectical, ignoring not only the myths that Easterners projected against the West—ignorant stereotyping is, if nothing else, a busy two-way street—but the ways the East itself reproduced the tropes of Orientalism: “A few hours in the library with the Middle Eastern section of the Summary of World Broadcasts will do wonders for anyone who thinks reification and discursive interpellation are the prerogative of Western writers on the region.” In fact, Islamists can be among the greatest Orientalists, for many insist on an Islam that is eternal, opaque and monolithic.

Most of all, though, Halliday questioned the assumption that the presumably impure origin of an idea necessarily negates its truth value. “Said implies that because ideas are produced in a context of domination, or directly in the service of domination, they are therefore invalid.” Carried to its logical conclusion, of course, this would entail a rejection of modernity itself—from its foundational ideas to its medical, technological and scientific advances—for all were produced “in the context of imperialism and capitalism: it would be odd if this were not so. But this tells us little about their validity.” (“Antiimperialism” and “self-determination” are, we might note, Western concepts, just as penicillin, the computer, the machine gun and the atom bomb are Western inventions.) And he questioned a key tenet of postcolonial studies and postcolonial politics: that the powerless are either more insightful or more ethical than their oppressors. “The very condition of being oppressed…is likely to produce its own distorted forms of perception: mythical history, hatred and chauvinism towards others, conspiracy theories of all stripes, unreal phantasms of emancipation.” Suffering is not necessarily the mother of wisdom.

But if Halliday was a foe of the simplicities of Orientalism, he was equally opposed to Samuel Huntington’s notion of “the clash of civilizations”—a concept that, he pointed out, was as beloved by Osama bin Laden as by neoconservatives—and to essentialist fictions like “the Islamic world” and “the Arab mind.” (On this, he and Said certainly agreed.) More than fifty diverse countries contain Muslim majorities; the job of the intellectual—whether located inside or outside the region—was to specify and demystify rather than deal in lumpy, ignorant generalities. “Disaggregation and explanation, rather than invocations of the timeless essence of cultures,” was the Mideast scholar’s prime task, Halliday insisted. He rejected mystified concepts such as Islamic banking and Islamic economics (“Anyone who has studied the economic history of the Muslim world…will know that business is conducted as it is everywhere, on sound capitalist principles”); the Islamic road to development (Iran’s economy was “a perfectly recognisable ramshackle rentier economy, laced with corruption and inefficiency”); and Islamic jurisprudence (Sharia, Halliday noted, has virtually no basis in the Koran). Echoing E.P. Thompson, Halliday argued that much of what passes for the ancient and authentic in the Islamic world—including Islamic fundamentalism itself—is the creation of modernity, and can be productively analyzed only within a political context.

Halliday proposed that even the Iranian Revolution—with its mobilization of the masses, consolidation of state power, repressive security institutions and attempts to export itself—had, despite its peculiar ideology, reprised the basic dynamics of modern, secular revolutions: “not that of Mecca and Medina in the seventh century but that of Paris in the 1790s and Moscow and St Petersburg in the 1920s.” Islam, Halliday insisted, could not explain the trajectory of that revolution or, for that matter, the politics of the greater Middle East.