#Muhammad: the Last Prophet 2002

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A few 2D Muslim heroes

#muslim#animation#disney#richard rich#dreamworks#kamala khan#ms. marvel#the boy and the king 1992#Muhammad: the Last Prophet 2002#the singing princess 1949#La Rosa di Baghdad 1949#egypt#gundam wing#setsuna#princess zeila#princess jasmine#aladdin#sinbad: legend of the seven seas#the thief and the cobbler#princess yum yum#x-men#dust

156 notes

·

View notes

Link

By CALVIN WOODWARD, ELLEN KNICKMEYER and DAVID RISING

September 10, 2021 GMT

In the ghastly rubble of ground zero’s fallen towers 20 years ago, Hour Zero arrived, a chance to start anew.

World affairs reordered abruptly on that morning of blue skies, black ash, fire and death.

In Iran, chants of “death to America” quickly gave way to candlelight vigils to mourn the American dead. Vladimir Putin weighed in with substantive help as the U.S. prepared to go to war in Russia’s region of influence.

Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi, a murderous dictator with a poetic streak, spoke of the “human duty” to be with Americans after “these horrifying and awesome events, which are bound to awaken human conscience.”

From the first terrible moments, America’s longstanding allies were joined by longtime enemies in that singularly galvanizing instant. No nation with global standing was cheering the stateless terrorists vowing to conquer capitalism and democracy. How rare is that?

Too rare to last, it turned out.

___

Civilizations have their allegories for rebirth in times of devastation. A global favorite is that of the phoenix, a magical and magnificent bird, rising from ashes. In the hellscape of Germany at the end of World War II, it was the concept of Hour Zero, or Stunde Null, that offered the opportunity to start anew.

For the U.S., the zero hour of Sept. 11, 2001, meant a chance to reshape its place in the post-Cold War world from a high perch of influence and goodwill as it entered the new millennium. This was only a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union left America with both the moral authority and the financial and military muscle to be unquestionably the lone superpower.

Those advantages were soon squandered. Instead of a new order, 9/11 fueled 20 years of war abroad. In the U.S., it gave rise to the angry, aggrieved, self-proclaimed patriot, and heightened surveillance and suspicion in the name of common defense.

It opened an era of deference to the armed forces as lawmakers pulled back on oversight and let presidents give primacy to the military over law enforcement in the fight against terrorism. And it sparked anti-immigrant sentiment, primarily directed at Muslim countries, that lingers today.

A war of necessity — in the eyes of most of the world — in Afghanistan was followed two years later by a war of choice as the U.S. invaded Iraq on false claims that Saddam Hussein was hiding weapons of mass destruction. President George W. Bush labeled Iran, Iraq and North Korea an “axis of evil.”

Thus opened the deep, deadly mineshaft of “forever wars.” There were convulsions throughout the Middle East, and U.S. foreign policy — for half a century a force for ballast — instead gave way to a head-snapping change in approaches in foreign policy from Bush to Obama to Trump. With that came waning trust in America’s leadership and reliability.

Other parts of the world were not immune. Far-right populist movements coursed through Europe. Britain voted to break away from the European Union. And China steadily ascended in the global pecking order.

President Joe Biden is trying to restore trust in the belief of a steady hand from the U.S. but there is no easy path. He is ending war, but what comes next?

In Afghanistan in August, the Taliban seized control with menacing swiftness as the Afghan government and security forces that the United States and its allies had spent two decades trying to build collapsed. No steady hand was evident from the U.S. in the harried, disorganized evacuation of Afghans desperately trying to flee the country in the first weeks of the Taliban’s re-established rule.

Allies whose troops had fought and died in the U.S-led war in Afghanistan expressed dismay at Biden’s management of the U.S. withdrawal, under a deal President Donald Trump had struck with the Taliban.

THE ‘HOMELAND’

In the United States, the Sept. 11 attacks set loose a torrent of rage.

In shock from the assault, a swath of American society embraced the us vs. them binary outlook articulated by Bush — “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists” — and has never let go of it.

You could hear it in the country songs and talk radio, and during presidential campaigns, offering the balm of a bloodlust cry for revenge. “We’ll put a boot in your ass, it’s the American way,” Toby Keith promised America’s enemies in one of the most popular of those songs in 2002.

Americans stuck flags in yards and on the back of trucks. Factionalism hardened inside America, in school board fights, on Facebook posts, and in national politics, so that opposing views were treated as propaganda from mortal enemies. The concept of enemy also evolved, from not simply the terrorist but also to the immigrant, or the conflation of the terrorist as immigrant trying to cross the border.

The patriot under threat became a personal and political identity in the United States. Fifteen years later, Trump harnessed it to help him win the presidency.

THE OTHERING

In the week after the attacks, Bush demanded of Americans that they know “Islam is peace” and that the attacks were a perversion of that religion. He told the country that American Muslims are us, not them, even as mosques came under surveillance and Arabs coming to the U.S. to take their kids to Disneyland or go to school risked being detained for questioning.

For Trump, in contrast, everything was always about them, the outsiders.

In the birther lie Trump promoted before his presidency, Barack Obama was an outsider. In Trump’s campaigns and administration, Muslims and immigrants were outsiders. The “China virus” was a foreign interloper, too.

Overseas, deadly attacks by Islamic extremists, like the 2004 bombing of Madrid trains that killed nearly 200 people and the 2005 attack on London’s transportation system that killed more than 50, hardened attitudes in Europe as well.

By 2015, as the Islamic State group captured wide areas of Iraq and pushed deep into Syria, the number of refugees increased dramatically, with more than 1 million migrants, primarily from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, entering Europe that year alone.

The year was bracketed by attacks in France on the Charlie Hebdo magazine staff in January after it published cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, and on the Bataclan theater and other Paris locations in November, reinforcing the angst then gripping the continent.

Already growing in support, far-right parties were able to capitalize on the fears to establish themselves as part of the European mainstream. They remain represented in many European parliaments, even as the flow of immigrants has slowed dramatically and most concerns have proved unfounded.

THE UNRAVELING

Dozens of countries joined or endorsed the NATO coalition fighting in Afghanistan. Russia acquiesced to NATO troops in Central Asia for the first time and provided logistical support. Never before had NATO invoked Article 5 of its charter that an attack against one member was an attack against all.

But in 2003, the U.S. and Britain were practically alone in prosecuting the Iraq war. This time, millions worldwide marched in protest in the run-up to the invasion. World opinion of the United States turned sharply negative.

In June 2003, after the invasion had swiftly ousted Saddam and dismantled the Iraqi army and security forces, a Pew Research poll found a widening rift between Americans and Western Europeans and reported that “the bottom has fallen out of support for America in most of the Muslim world.” Most South Koreans, half of Brazilians and plenty more people outside the Islamic world agreed.

And this was when the war was going well, before the world saw cruel images from Abu Ghraib prison, learned all that it knows now about CIA black op sites, waterboarding, years of Guantanamo Bay detention without charges or trials — and before the rise of the brutal Islamic State.

By 2007, when the U.S. set up the Africa Command to counter terrorism and the rising influence of China and Russia on the continent, African countries did not want to host it. It operates from Stuttgart, Germany.

THE SUCCESSES

Over the two decades, a succession of U.S. presidents scored important achievements in shoring up security, and so far U.S. territory has remained safe from more international terrorism anywhere on the scale of 9/11.

Globally, U.S.-led forces weakened al-Qaida, which has failed to launch a major attack on the West since 2005. The Iraq invasion rid that country and region of a murderous dictator in Saddam.

Yet strategically, eliminating him did just what Arab leaders warned Bush it would do: It strengthened Saddam’s main rival, Iran, threatening U.S. objectives and partners.

Deadly chaos soon followed in Iraq. The Bush administration, in its nation-building haste, failed to plan for keeping order, leaving Islamist extremists and rival militias to fight for dominance in the security vacuum.

The overthrow of Saddam served both to inspire and limit public support for Arab Spring uprisings a few years later. For if the U.S. showed people in the Middle East that strongmen can be toppled, the insurgency demonstrated that what comes next may not be a season of renewal.

Authoritarian regimes in the Middle East pointed to the post-Saddam era as an argument for their own survival.

The U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq killed more than 7,000 American military men and women, more than 1,000 from the allied forces, many tens of thousands of members of Afghan and Iraqi security forces, and many hundreds of thousands of civilians, according to Brown University’s Costs of War project. Costs, including tending the wars’ unusually high number of disabled vets, are expected to top $6 trillion.

For the U.S., the presidencies since Bush’s wars have been marked by an effort — not always consistent, not always successful — to pull back the military from the conflicts of the Middle East and Central Asia.

The perception of a U.S. retreat has allowed Russia and China to gain influence in the regions, and left U.S. allies struggling to understand Washington’s place in the world. The notion that 9/11 would create an enduring unity of interest to combat terrorism collided with rising nationalism and a U.S. president, Trump, who spoke disdainfully of the NATO allies that in 2001 had rallied to America’s cause.

Even before Trump, Obama surprised allies and enemies alike when he stepped back abruptly from the U.S. role of world cop. Obama geared up for, then called off, a strike on Syrian President Bashar Assad for using chemical weapons against his people.

“Terrible things happen across the globe, and it is beyond our means to right every wrong,” Obama said on Sept. 11, 2013.

THE NEWISH ORDER

The legacies of 9/11 ripple both in obvious and unusual ways.

Most directly, millions of people in the U.S. and Europe go about their public business under the constant gaze of security cameras while other surveillance tools scoop up private communications. The government layered post-9/11 bureaucracies on to law enforcement to support the expansive security apparatus.

Militarization is more evident now, from large cities to small towns that now own military vehicles and weapons that seem well out of proportion to any terrorist threat. Government offices have become fortifications and airports a security maze.

But as profound an event as 9/11 was, its immediate effect on how the world has been ordered was temporary and largely undone by domestic political forces, a global economic downturn and now a lethal pandemic.

The awakening of human conscience predicted by Gadhafi didn’t last. Gadhafi didn’t last.

Osama bin Laden has been dead for a decade. Saddam was hanged in 2006. The forever wars — the Afghanistan one being the longest in U.S. history — now are over or ending. The days of Russia tactically enabling the U.S., and China not standing in the way, petered out. Only the phoenix lasts.

___

Rising reported from Bangkok; Knickmeyer and Woodward from Washington. AP National Security Writer Robert Burns contributed to this report.

https://apnews.com/article/911-20-years-world-affairs-cc497f11743fcbd48b0b3e0c3ed2da5f

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reception of Gender Diversity in Indonesia and Women’s Erotic Literature

Selections from "Between sastra wangi and perda sharia: debates over gendered citizenship in post-authoritarian Indonesia," Susanne Schröter, Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs (RIMA), 48(1), 2014.

In Indonesia, we encounter a somewhat paradoxical situation where gender deviance is tolerated in many quarters while there is, at the same time, an increasingly repressive-patriarchal gender mainstream. This becomes particularly apparent in the issue of acceptance of queer lifestyles. After the end of the New Order period, the emerging liberalisation in the urban areas included that aspect as well. A group called Q-Munity has organised an annual queer film festival, the Q!Festival, in Jakarta since 2002 and activists join in public debates, trying to reduce prejudice and to put an end to discrimination. Within the women’s rights network, Kartini, a training manual was developed to strengthen the position of non-heteronormative life models (Bhaiya und Wieringa 2007), and Siti Musdah Mulia proclaimed in the newspaper Jakarta Globe of 23 September 2009 that lesbian desire was created by God just like its heterosexual counterpart and hence must be accepted as natural. Until today, her statement triggers controversial discussions within Indonesia and beyond.

As could be expected, this unusual awakening was criticised by Islamist hardliners as an adoption of Western decadence. Performance venues of the Q! Festival were repeatedly raided by ‘goon squads’ and in 2010 Surabaya became the site of an éclat that was even covered by the international media. It was sparked by plans of the Asian branch of the International Lesbian and Gay Association to hold an international conference in March of that year. There had been similar conventions before in Mumbai, Cebu and Chiang Mai. The organisers were eager to be as discrete as possible in order to avoid protests. There was to be no Gay Pride Parade, and the organisers planned to publish a press release only on the last day of the event. Due to an unlucky coincidence, however, the local media learned about the planned event in its run-up and there were quick reactions by Islamic organisations. Statements were issued by religious authorities, claiming that homosexuality is irreconcilable with both Indonesian culture and Islam. Such language immediately mobilised the Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam) and the Indonesian fraction of Hizb-ut Tahrir[14] to take militant action against the organisers. As a result, the local authorities prohibited the conference and those participants who had already arrived were besieged at their hotels by the mob until they were brought to safety under police protection (Vacano 2010).

These incidents appear to be at odds with the supposedly tolerant attitude towards gender variances in Indonesia as described by anthropologists such as Boellstorff (2005), Peletz (2009), Davis (2010) and Blackwood (2010). These scholars base their claims on the existence of so-called third and fourth genders rooted in local social orders. An often-cited example of this are the Bugis of South Sulawesi who use five gender terms: besides women and men, there are calalai (masculine women), calabai (feminine men), and bissu (ritual experts and shamans who are ambiguous in terms of gender). The bissu have always particularly attracted the attention of anthropologists, who interpreted them as a culturally-accepted variant of non-binary gender. In the Bugis system of gender categories, they are classified as calabai, that is, individuals with a male body and a feminine or ambivalent habitus. They are viewed as embodying a pre-Islamic, double-gendered Supreme Being which is attributed the ability to mediate between humans and spirits; hence, they act as healers and shamans. There is some debate, however, among anthropologists about whether the existence of this phenomenon can actually be interpreted as an indicator of tolerance and liberalism. Birgit Röttger-Rössler, who has done fieldwork among the Bugis, is sceptical, and even objects to applying the term ‘third gender’. According to her, calabai are ‘institutionalised, socially-accepted variants or subcategories of the male gender’ (Röttger-Rössler 2009:287, translation mine). She adds that these types of transgenderism can by no means be interpreted as a negation of heteronormative gender concepts. The reverse is true: they reinforce the latter. As Röttger-Rössler sees it, the order legitimated by this exception is not only ‘defined clearly and rigidly’(Röttger-Rössler 2009:287–8), but also asymmetrical, putting women at a disadvantage.

On top if this, the mere existence of a local ‘third gender’ does not allow the conclusion that local communities are generally characterised by a liberal attitude towards gender issues. This becomes particularly evident when modern phenomena of transgression, which are usually referred to as queer, meet local forms of deviance. The mobilisation of queer activists in Indonesia and the resulting Islamic counteroffensive is a well-documented example of this.

The same applies to shifts in local gender structures that were triggered by the general climate of open-mindedness after the end of the New Order. In the year when the conference in Surabaya was wrecked by conservative moral ideas, there was also a remarkable public debate on local Indonesian transgenders who are subsumed by the collective term of waria.[15] The debate was sparked by a ‘Miss Aceh Transsexual’ beauty pageant held in February 2010. Many people in Aceh have ambivalent and contradictory attitudes towards waria. On the one hand, they view the latter’s existence as a disgrace for the community; on the other hand, waria are tolerated half-heartedly, not least because men secretly relish their sexual services. Waria often use their beauty parlours and hairdressing salons as brothels and engage in prostitution in the semi-clandestine red light district of the capital Banda Aceh. It is obvious that neither Aceh society nor the police intend to actually eliminate this option for extramarital sex, which is punishable under current legislation. Representatives of the authorities, however, take advantage of the waria’s extralegal status and arbitrary arrests as well as rape in police custody are common. Everyday discrimination, humiliation, and assaults by the sharia police are rampant. In the wake of the devastating tsunami in 2004, which was interpreted by Islamic clerics as a warning to disobedient believers, waria were repeatedly expelled from their homes and businesses because their neighbours feared that their presence might evoke the wrath of God to descend upon them again.

In Indonesia, both the human rights and the Qur’an and Sunna are invoked in the discussion about whether or not the existence of waria is legitimate. In Aceh, more importance is attached to the religious narratives of justification, however, than to secular reasoning, because Islam is viewed as the measure of all things. In the end, phenomena that are incompatible with the commandments of Allah will not gain acceptance. The experts disagree, however, about what is compatible with Islam, particularly if waria make their appearance in modern contexts. The pageant mentioned above, where they performed in burlesque costumes, sparked a pan-Indonesian controversy which dominated the headlines of the local and national press for several days. Well-known politicians, activists, and Islamic clerics piped up to express their opinion. The majority of the religious contributions condemned waria as being immoral and sinners, while secular commentators came to their defence, referring to minority rights.

I had the opportunity to discuss that issue in March 2010 with students at the State Islamic University (Universitas Islam Negeri, UIN) in Yogyakarta and at the Gadjah Mada University (UGM) which is also located in Yogyakarta. The Islamic students, in particular, engaged in a lively debate about whether the Qur’an makes a clear statement about the matter and what the prophet Muhammad said about it. This was their sole criterion for tolerating or condemning waria. On the personal level, the subject did not trigger any emotions in them; it was a purely matter-of-fact discussion without any recourse to moral categories. My colleague Sahiron Syamsuddin, a respected Islamic scholar with whom I held the event, eventually made an important point. He said that three gender categories were already known in Muhammad’s time: men, women, and khunta--transgenders who resembled the waria. He went on to explain that the third gender had fallen into oblivion due to subsequent patriarchal developments. This was acceptable to the students. Sahiron’s reasoning is typical of so-called ‘progressive’ Muslims who attempt to substantiate liberal ideas with little-known data from the Islamic past or new interpretations of the Qur’an and Sunna.

As becomes apparent from the abovementioned examples, upon closer examination, the much-cited Indonesian open-mindedness with regard to gender variances turns out to be a restrictive straightjacket into which some phenomena can be fitted, while others cannot. Transgender individuals are tolerated and may even hold respected positions, provided that they stay within narrow, strictly-defined social confines or already-accepted cultural constructs. Above all, they are expected to be inconspicuous. As long as a beauty pageant is held in a village, whether or not the event is made into a scandal depends on the social relations between the individual actors. At the national level, it is not possible to rely on such local relations. Other narratives of justification then take effect, particularly narratives backed by Islam. It appears that only a minority of the Indonesian Muslims subscribe to progressive interpretations of the Qur’an and the Islamic traditions, and my colleague Syamsuddin would certainly have had a hard time if rhetorically-versed Islamists had participated in the discussion. According to a study conducted in 2013 by the Pew Research Center, 93 per cent of all Indonesians disapprove of homosexuality. Thus, in terms of tolerance, the country is behind Malaysia (86 per cent) and Pakistan (87 per cent) and at the same level as Palestine. As has been noted by Jamison Liang, homophobia is on the rise (Liang 2010). This development is due not only to the strength gained by a conservative, partly militant Islam, but also to the fact that by now there is a public debate on the issue of gender deviance.

----

The virulently liberal face of Indonesian culture, despite Islamist zealotry, is also represented by the genre of female erotic literature. Called sastra wangi (fragrant literature) it caused an international sensation.[12] Writers such as Djenar Maesa Ayu, Ayu Utami, Fira Basuki, Dewi Lestari, and Nova Riyanti Yusuf picked out incest, extramarital sex, and homosexuality as central themes. They were not afraid of giving drastic descriptions of sexuality and they played offensively with the breach of all social conventions (Hatley 1999; Listyowulan 2010). One of the most prominent examples is Ayu Utami’s book Saman, of which more than one hundred thousand copies were sold in Indonesia. The novel is about the sexual adventures of three young women from good families, about split identities and the transgression of patriarchal moral ideas. Shakuntala, one of the protagonists, deflowers herself with a spoon and feeds the hymen to a dog. Later, she enters into a lesbian relationship in which she takes the male-connoted part. These are the scandal-provoking parts of the novel. It also has, however, another, political dimension which centres on the priest Saman. During a conflict, he takes sides with oppressed rubber farmers who are struggling against dispossession. He is denounced as their leader, arrested and tortured.

[cw for discussion of incest, child sexuality/assault]

In Djenar Maesa Ayu’s Menjusuh Ayah (Suckled by the Father), a woman recounts the sexual childhood experiences she had with older men, including her father. She states that as a baby she was not fed her mother’s milk, but her father’s semen. When she confronts her father with that story, he accuses her of lying and hits her with his belt. She insists, however, on her version of the past. The first-person narrator tells the reader that her father eventually refused to feed her any longer. Hence, she turned to his friends as a child. ‘I liked the way they slowly pushed down my head and allowed me to suckle there for a long time’ (Ayu 2008:95). When one of her father’s friends penetrates her, she kills him: ‘I am a woman, but I am not weaker than a man’, she writes, ‘because I have not suckled on mother’s breast’ (Ayu 2008:97).

[end cw]

The new erotic women’s literature led to a controversial discussion in Indonesia. The term sastra wangi itself alludes to the public erotic self-staging of the women, which was eagerly picked up by the media. Many stories about the young writers opened with exact descriptions of their looks, mentioning the high heels, the strapless t-shirts, the long loose hair, or the fact that the audience smoked and consumed alcohol during the readings. Like the provocative titles and texts, the media stagings brought fast fame and high sales figures. On the other hand, the women were accused of using sex as a marketing strategy. Not surprisingly, criticism of the taboo breaches came from the religious side, while secular-urban intellectuals mostly appreciated the new literary awakening. Saman won several awards, including a writing contest of the Jakarta Art Institute in 1997 and an award of the Jakarta Art Council (Dewan Kesenian Jakarta) for best novel in 1998. In 2000, Ayu Utami won the Claus Award in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, there has been some reserve on the part of literary scholars. Katrin Bandel criticises the unquestioned male perspective of the sastra wangi (Bandel 2006:115), Arnez and Dewojati find fault with the virulent phallocentrism (Arnez and Dewojati 2010).[13] Positive appraisal, however, prevails in the overall judgment. According to Arnez and Dewojati, the issue of whether sastra wangi can be called emancipatory is still controversial, but nevertheless ‘it can be claimed that in modern Indonesian literature such an open discussion of sexuality and female desire has not taken place before, especially not in such an outspoken language’ (Arnez and Dewojati 2010:20).

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Treat Your S(h)elf

The Places In Between by Rory Stewart

“I offered Asad money but he was horrified. It seemed a six-hour round trip through a freezing storm and chest deep snow was the least he could do for a guest. I did not want to insult him but I was keen to repay him in some way. I insisted, feeling foolish. He refused five times but finally accepted out of politeness and gave the money to his companion.Then he wished me luck and turned up the hill into the face of the snowstorm."

- Rory Stewart

Just weeks after the fall of the Taliban in January of 2002 Scotsman Rory Stewart began a walk across central Afghanistan in the footsteps of 15th Century Moghul conqueror Emperor Babur and along parts of the legendary Silk Road, from Herat to Kabul. He'd find himself in the course of twenty-one months encountering Sunni Kurds, Shia Hazala, Punjabi Christians, Sikhs, Kedarnath Brahmins, Garhwal Dalits, and Newari Buddhists. He said he wanted to explore the "place in between the deserts and the Himalayas, between Persian, Hellenic, and Hindu culture, between Islam and Buddhism, between mystical and militant Islam." He described Afghanistan as "a society that was an unpredictable composite of etiquette, humour, and extreme brutality."

The Places in Between is Stewart's account of walking across Afghanistan from Herat to Kabul in January 2002. The book was the winner of the Royal Society of Literature Ondaatje Award and the Spirit of Scotland Award and shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award, the John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize and the Scottish Book of the Year Prize.

I first read the book as a teenager a few years after it came out when I was spending a few months doing voluntary work for an Afghan children’s charity in Peshawar, Pakistan with my older sister who was a junior doctor at the time.

I read it on the rocky bus ride from Peshawar, Pakistan and into Afghanistan from Jalalabad to Kabul with my sister and her colleagues. I avidly read the book because I already knew the author through my oldest brother but from a distance because of our respective ages. Little did I realise then that I would be back in Afghanistan a few years later but this time in uniform doing my tour in Afghanistan flying combat helicopters against the Taliban.

I had the book with me (but a newer copy) and it took on a greater prescience precisely because as soldiers, even from the most senior officers on down, we privately questioned what the hell were we really accomplishing in a country ravaged by war since the Soviet invasion in 1979 (and that’s being generous given how history has buried empires into the graveyard of Afghanistan as a testament to their hubris).

Maybe it was hubris or perhaps it was that adventurous strain that needs to be scratched that led Rory Stewart to undertake his madcap journey. Stewart did the entire journey on foot, refusing any other form of transportation (and at one point going back and redoing a section of the walk when he couldn't turn down a vehicle ride). He took an uncommon route straight through the centre of the country and the heart of the mountains, instead of the more common route through the south that bypasses the dangerous mountain passes. This choice was partly because it was shorter, partly because the south was still partially controlled by the Taliban, and partly I suspect (though he doesn't say this explicitly) because it's the less-discussed and less-known route, even today.

This is, therefore, a sort of travel book, describing places that 99.99% of readers in the Western world are very unlikely to ever go. It's also unavoidably political, since Afghanistan is unavoidably political. However, unlike many travel books and many books with political overtones, it's carefully observational, documentary, and quietly understated in a way that gives the reader room to analyse and consider. Stewart focuses on his specific journey and concise, detailed descriptions of what he encountered and lets any broader implications of what he saw emerge from the reader's evaluation. He describes how he reacts to the remarkable natural beauty and almost-forgotten ruins that he encounters, giving the reader a frame and a sense of the emotional impact, but he's not an overbearing presence in the book. The story is clearly personal, but he doesn't dominate it. This is a very difficult line to walk, and I don't recall the last time I've seen it walked as deftly.

Instead there is a real sense that the author has gotten over the novelty of travelling and is more focused on the fundamental circumstances he encounters. The book overall is a fascinating read and there is much to be learned about the epistemologies driving the Afghan people and how different interpretations of Muslim teachings (and likewise, any teachings) can create small, but significant differences between neighbours. He has a gift for vividly describing the people and the landscape without injecting himself too much into the scene.

I suspect every reader will take different things from The Places in Between.

For some readers unaccustomed to the culture of Afghanistan, they would find it distressing to read how dogs are treated in Afghanistan. It's said Prophet Muhammad once cut off part of his own garment rather than disturb a sleeping cat. Unfortunately, he didn't feel equal affection for dogs, and they're "religiously polluting." They're not pets, and they're never petted. A quarter of the way in his journey Stewart has a toothless mastiff pressed upon him by a villager and he named him Babur. The evidence of past abuse could be seen in missing ears and tail, and someone told Stewart the dog was missing teeth because they'd been knocked out by a boy with rocks. Stewart found the dog a faithful companion and said he'd call him "beautiful, wise, and friendly" but that an Afghan, though he might use such terms to describe a horse or hawk would never use it to describe a dog.

But I knew all this growing in Pakistan and India as a small girl. Friends would look perplexed that we Brits - or any Westerners - have dogs or cats as pets and even see them as part of the family.

For me though two big themes stuck out when I first read the book.

One of the things that struck me most memorably is the spider’s web of personal loyalties, personal animosities, different tribes and history, and complexity of Afghan politics that Stewart walks through. Afghanistan is not coherent or cohered in the way that those of us living in long-settled western countries assume when thinking about countries. While there are regions with different ethnicities or dominant tribes, it doesn't even break down into simple tribal areas or regions divided by religion. The central mountain areas Stewart walked through are very isolated and have a long history and a complex web of rivalries, differing reactions to various central governments, and different connections. Stewart meets people who have never traveled more than a few miles from their village, and people who can't go as far as his next day's stop because they'd be killed by the people in the next village. It becomes clear over the course of his journey why creating a cohesive western-style country with unified national rule is far less likely and more difficult than is usually portrayed in the Western news media. The reader slowly begins to realise that this may not be what the Afghans themselves want, and some of the reasons why not.

A large part of that recent history is violent, and here is where Stewart's ability to describe and characterise the people he meets along the way shines. It is a tenet of both Islam and the local culture to give hospitality to travellers, which is the only thing that makes this sort of trip possible. Stewart is generally treated exceptionally well, particularly given the poverty of the people (meat is extremely rare, and most meals are bread at best), but violence and fighting fills the minds and experiences of most people he meets. He memorably observes at one point that one of his temporary companions describes the landscape in terms of violent events. Here, he shot four soldiers. There, two people were killed. Over there is where they ambushed a squad of Russians. It's striking how, after decades of fighting either for or against first the Russians and then the Taliban shapes and marks their mental map of the world. It's likely that few of the people Stewart meets are entirely truthful with him, but even that is an intriguing angle on what they care to lie about, what they think will impress him, and how the Afghan people he encounters display status or react to the unusual.

The second big theme that stuck out for me on a personal note was how Stewart respectfully weaves the wonder of history with the sad lament of the destructive loss heritage on his travels. In the book, Stewart followed roughly the same path as Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, did in 1504 at roughly the same time of year. He quotes occasionally from the Baburama, Babur's autobiography, which adds a depth of history to the places Stewart passes through. The Minaret of Jam in the mountains of western Afghanistan is one of the (unfortunately rare) black and white pictures in the centre of this book, and Stewart describes the legendary Turquoise Mountain, the lost capital of a mountain kingdom destroyed by the son of Genghis Kahn in the 1220s, of which the minaret may be the last surviving recognisable remnant. He describes the former Buddhist monasteries at Bamyan in Hazarajat (the region of central Afghanistan populated by the Hazara) and the huge empty alcoves where giant statues of the Buddha had stood for sixteen centuries until destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. This book then is full of history of which is described with a discerning eye for necessary detail.

How Afghanistan's precious historical and cultural legacy was being destroyed even back in 2002 is heart breaking to read. I think many Westerners certainly know about how the Taliban dynamited the giant Bamiyan Buddha statues over a millennium old because they considered them "idols." Just as profound a loss is discovered by Stewart in his travels. There is a legendary lost city, the "Turquoise Mountain" of the pre-Moghul Ghorid Empire. Archeologists couldn't find it - but when passing through the area, Stewart had found villagers who had, and were looting artefacts with no care for the archeological context or the damage they were doing to the site, selling the priceless wares for the equivalent of a couple of dollars on the black market. This is what he tells us about his discussion with the villagers about the lost city:

"It was destroyed twice," Bushire added, "once by hailstones and once by Genghis." "Three times," I said. You're destroying what remained." They all laughed.

Even as I write this I can’t help but think this episode eerily echoes the madness gripping us in Britain, Europe, and the US (albeit for different reasons) in defacing and pulling down historical statues in wanton in acts of extreme ideological vandalism.

Overall I enjoyed the ‘peace’ of this book as there is a constant tone of a simple purpose. There are some moments along the way that are quite confronting and even frustrating, but so many that are warm and celebratory of the Afghan belief in hospitality.

Perhaps others will differ but I didn’t find too many irritating passages that wax-poetic on the evolution of the traveller. Stewart’s writing style is clinical; completely void of sentimentality, he never allows his own initial or personal meditations on these places overtake his observations, written with much hindsight. Whether being harassed by local soldiers or struggling through snowdrifts Stewart does not bridge a gap with the reader to really get a sense of who he his, as if his own story would detract from the crucial timing of his recordings of this landscape and its people.

His own biography is something out of John Buchan. The son of Scottish colonial civil servant who was born in Hong Kong and grew up in the Far East (and subsequently the second most senior official in the British secret intelligence) before being packed off back to England to Dragon School, Eton and onto Balliol, Oxford to study PPE. A short stint with the Black Watch regiment (as his father and uncle before him) before joining the British Foreign Office and work in some hot spots of the world, including a stint as deputy governor in the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq after 2003. He went on to work at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard before returning to the UK to successfully run as a Conservative MP in his native Scotland. Served as a minister in different ministries under Prime Minister Theresa May’s government and improbably came close to upsetting the coronation of Boris Johnson as the next leader of the Conservative party. He resigned from the party rather than be purged and made an unsuccessful bid to run as an independent candidate for London Mayor. He continues to writer and author travel books and front documentaries. He has a storied background but he wears it very lightly.

Of course there is a conceit to the book which in a sense all travel books of this kind that largely goes unquestioned. I don’t think it’s wrong to question a certain kind of entitlement that pervades these kind of books, no matter how much I enjoy reading them especially about countries you have traveled to and know a little bit about. Stewart after all embarks on a journey ‘planning’ to rely on the proverbial kindness of strangers because that is an Islamic cultural and religious value. Try planning a trip anywhere in Western Europe or the USA and Canada. I cannot imagine anyone walking across America, or England and Scotland for that matter, who would believe that he was entitled to expect food, shelter and assistance because he asked for it.

And he does it - as have countless travellers before and after him. Because Stewart succeeds in his journey, he is evidence of an astonishing degree of Afghan Muslim hospitality and generosity. As a back packer who has done it rough not just in Afghanistan but also neighbouring Central Asia as well as Pakistan, India, and China I can see why it might rub some up the wrong way. But I also think it’s not cultural or some sort of colonial arrogance on Stewart’s part. It’s hard to articulate but it’s really a kind of cultured sensitivity of people and lands you already are familiar with or know well from childhood.

Certainly for Rory Stewart - and myself - didn’t exclusively grow up in England and Scotland but in the Eastern post-colonial countries of the ex-British Empire that afforded a privileged childhood (privileged as in a real cultural engagement and immersion) that left a deep appreciation and respect for those countries cultures and traditions. I believe for the vast majority of Western back packers who take adventurous treks across these lands they do so partly out of genuine respect and understanding of different cultures.

For instance, the legacy of this book has been that Rory Stewart has spear headed a long term project called Turquoise Mountain. Alongside his partners, they have been re-creating the "downtown" river district in Kabul and restoring it to it's former glory. They have opened schools for people to re-learn the ancient arts of carving, weaving, architecture, etc. They have supported efforts to restoring city blocks that have been covered in a mountain of trash, and restoring homes where families have lived for centuries. And all for free. The Afghan have never been sure why someone would be doing this out of the goodness of their hearts, but that the poignant irony is that the goodness began with them through their hospitality of the stranger.

The kindness to strangers is a real thing in this part of the world. Kindness to strangers has it roots in fear that the strangers might be gods or their messengers alongside the pragmatic need that strangers in a strange land might need assistance. I sometimes wonder how is it we cannot show the same unabashed kindness to strangers to our homes?

However you slice it, you have to admire Stewart for his mostly un-aided walk across Afghanistan. It does take a certain kind of ballsiness to do it. He carried just his clothes and a sleeping bag (and money), trusting that the villagers along the way would put him up for the night and feed him. He got very sick (diarrhoea and dysentery), was at constant risk of freezing to death in the mountains, and had some very unpleasant encounters with Afghan soldiers in the last few days, after rejecting very strong advice not to walk through this section.

Strangely though nothing about this book is breathtaking of ‘Oriental exoticism’ beloved of Western imagination. Indeed nothing in this book is romanticised and nothing is placed on a pedestal. Stewart writes openly and honestly of all the people he met, those friendly, and those that would've preferred to rob him and leave him dead in a ditch. He's truthful and humorous, and I found myself walking alongside him, a sort of ghost following his rugged trail through mountains, valleys, and Buddhist monasteries.

Re-reading this book when I was doing my tour in Afghanistan with time to kill between missions, I wished George W. Bush and Tony Blair - and all the other Western leaders since these two - could have taken that walk with Stewart and learned the lessons he did. Stewart gives you a sense of the complexity and diversity of the culture and of Islam - and just how ludicrous and ignorant were the assumptions and goals imposed on the country by the invading Westerners. Indeed at the very end of his walk, Stewart reaches Kabul, the heart of the western intervention in Afghanistan and the place where all the political theorists and idealists came to try to shape the country. He describes the impact of seeing draft plans for a national government, which look ridiculous in the light of the country that he just traveled through.

It's a rare bit of political fire in the narrative that's all the more effective since it's one of the few bits of political commentary in the book. Indeed it’s all the more rich and relevant given its emergent commentary and background for the current war being fought there. Stewart necessarily tells only part of the story of Afghanistan, but he tells far more of the story than most will know prior to reading it. It should be mandatory reading for anyone making decisions about how to proceed in that region.

I would recommend anyone take a walk with Rory Stewart.

#books#reading#bookgasm#rory stewart#places in between#travel#afghanistan#trek#adventure#author#walking#treat your s(h)elf#personal#bio#army

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cartoon of Muhammad (PBUH) at church: Is this because of 'Cursed' Italy?

At present, the country that is currently in the worst condition due to coronavirus spreading worldwide in Italy. The Italian administration could not stop the procession of death. In the last about 5,000 people died. The Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte himself commented, 'We have lost control of the epidemic. We have died physically and mentally. Do not know what else to do. All solutions to the world are gone. Now the solution is just in the sky'. Such a situation has arisen in Italy. Many say Italy is a "cursed country" in Europe because of that incident. That curse is taking the country to the brink of destruction. But what is that history? Giovanni da Modena, one of the most famous Italian artists of the Renaissance era. This artist painted a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) 610 years ago. The old cartoon is still preserved in a Catholic church in Bologna, Italy. In the cartoon shown, the guards of the Hell (Nawzubillah) are torturing the Prophet (peace be upon him). The church is named San Petronio Basilica. In the first 2001, Muslims in Italy demanded the destruction of the cartoon. But the Italian government ignored that demand and arrested 5 Muslims in 2002 for opposing. The government claims they were planning to attack the church. Soon after that incident, a competition was created in Europe for the creation of the cartoon of the Prophet. In continuation of the same, on September 30, 2005 the European state of Denmark published 12 cartoons of the Prophet(s) in Jilan Postein. Later on February 1, France, Germany, Italy and Spain re-published cartoons by Muhammad (PBUH). On February 8, France's magazine, Shirley Hebdo, published a similar cartoon on the front page. It is important to note that recently in all these countries, Corona has become a terrible epidemic. At one point, Spain acknowledged a lot of restrictions and lifted restrictions on the country. Now let's see what way Italy goes! Meanwhile, in the middle of February 2006, a minister in the Italian government announced that he would make a t-shirt with a cartoon of the Prophet (PHUH) and distribute it to everyone. In April, a Christian religious magazine, 'Italian Studi Cattolici' in Italy published a new cartoon in imitation of Giovanni da Modena, preserved in the church of San Petronio Basilica. Immediately afterwards the subject of this cartoon spread around the world. From 2007, the Great MP of the Netherlands began his work on the cartoon of Islam and Muhammad (PBUH). Later, exhibitions were held in different countries. There are also some Islamist films. The whole thing was then patronized by the peoples of Europe. The anti-immigration movement started around this continent. Because most of the immigrants in those countries were Muslim. In these cases, at one point in Bangladesh, the anti-Islamic activities of Europe started. Islamist bloggers have emerged. They are sponsored by various countries in Europe. And at the top of this program is a European-based company, Penn International, headquartered in Britain. It is also alleged that some Bangladeshi boys bought them for money. They are given visas to travel to Europe. The cartoon about Muhammad (peace be upon him), the Qur'an and Islam around the world began in the last two decades, but it began in the Italian church. Recently, a question has been raised about the state of Italy after the coronavirus crashed. Despite such an advanced country in medicine, the procession of death does not stop in Italy. Many have claimed that in the current context, Italy should destroy the cartoon. Moreover, from the past history shows that during the time of the cartoon of Muhammad (peace be upon him) painted in Italy during the 1410 year, a terrible black plague was going on all over Europe, including Italy. The procession of death came to a halt after 1420. The world has been plagued by epidemics every 100 years. For example, in the 15th century, at the same time in the 16th century and in these times of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Europe has been the worst affected by these epidemics. This year's corona virus is also a witness.

1 note

·

View note

Text

PODSERIES: SAFEGUARDING SPEECH – PART 4 OF 13

The last blog was discussing the different types of speech a muslim must safeguard themself from.

The next danger of the tongue is foul language. This habit is undoubtedly a sin. The one who is obscene and bad mouthed is hated by Allah, the Exalted. This is confirmed in a Hadith found in Jami At Tirmidhi, number 2002. The one who angers Allah, the Exalted, is far away from His mercy and thus more susceptible to punishment in both worlds.

Foul language is any words which contradict modesty and good manners. It includes swearing and using shameless language. Wherever possible one should reference something indirectly rather than using shameless language.

The Holy Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, has made it clear in a Hadith found in Jami At Tirmidhi, number 1977, that a true believer does not utter foul words. So the one who makes this their habit should review their faith and sincerely repent from this evil trait. In fact, using foul language has been indicated as a branch of hypocrisy by the Holy Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, in a Hadith found in Jami At Tirmidhi, number 2027.

Replying to a shameless person is foolish and only leads to sins. For example, a person commits a major sin when they abuse their own parents. According to a Hadith found in Sahih Muslim, number 5973, this occurs when a person abuses another person's parents and the latter in response abuses their parents.

A muslim should strive to purify their tongue by only uttering sensible words otherwise they may speak a foul word which causes them to sink into Hell greater than the distance between the east and west of this world. This is confirmed in a Hadith found in Sahih Muslim, number 7481.

DIRECT PDF LINKS TO OVER 120 FREE SHAYKHPOD EBOOKS:

https://acrobat.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:4b1dfda6-78e9-36c9-8e4c-0291e83d4790

PodSeries: Speech - Part 4: https://youtu.be/y2G3SPnNYoY

PodSeries: Speech - Part 4: https://fb.watch/6SnbYK9P-q/

@shaykhpodpics - Infographics on Good Character

@shaykhpod-blog - Short Blogs on Good Character

5 MINS LIVE HADITH SESSIONS EVERY SUNDAY @ 9:45PM UK TIME

5 MINS LIVE TAFSEER SESSIONS EVERY THURSDAY @ 9:45PM UK TIME

5 MINS LIVE PODWOMAN SESSIONS EVERY TUESDAY @ 9:45PM UK TIME

– SET REMINDERS USING LINK:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCfii14TrSrTseShoeGLLhJw/videos

#Allah #ShaykhPod #Islam #Quran #Hadith #Prophet #Muhammad #Sunnah #Piety #Taqwa #Speech #Foul #Swearing #Cursing

0 notes

Photo

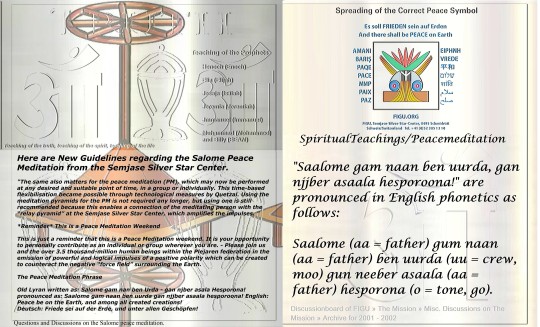

(Peace Meditation Pyramid is not required any longer)

SpiritualTeachings/Peacemeditation

The vowels in the following meditation sentence –

"Saalome gam naan ben uurda, gan njjber asaala hesporoona!" are pronounced in English phonetics as follows:

Saalome (aa = father) gum naan (aa = father) ben uurda (uu = crew, moo) gun neeber asaala (aa = father) hesporona (o = tone, go).

The meditation pyramid is placed either on a table if the person(s) meditates while sitting at the table, or in a slightly elevated position on a stool on the floor (the top of the antenna should be level with the meditators' foreheads). When several meditators of varying height participate in the meditation, an average level may be selected.

Using a compass, one of the pyramid's diagonal lines must be aligned due north; that is, the four corner points are directed toward the four cardinal points of the compass, namely North, South, East and West. When meditating as a group (two or more persons), we recommend that someone be designated beforehand who signals the beginning and the end of the peace meditation.

1. The meditators either sit at a normal height (no upholstered seats or the like) around a table, or else, they take a lotus/cross-legged position or sit on their haunches on a carpeted surface, whereby a small stool or a cushion, blanket, and so forth, is used as a seat. It is important that the spine and the head be relaxed and upright throughout the entire meditation period.

2. The minimum distance to the pyramid must be more than 50 cm (20"), measured from the chest to the pole of the antenna.

6. When the individual meditates at a table, both arms are extended toward the left and right sides of the pyramid in front of the individual, hands held open vertically with fingertips pointing toward the pyramid while the narrow edge of the palms rests on the table.

Posted on Saturday, March 16, 2002 - 03:46 pm:

From what I have heard, the FIGU does not give out specifications for pyramids anymore, nor do they ship them out anymore. The reason for this is that they usually are not made correctly and therefore will not work properly. They don't ship them anymore either because they get damaged during shipment. The only way to be sure to get a meditation pyramid according to the exact specifications of the Plejaren that works, is to go to the Center and get one, or have someone bring one back for you.

Posted on Saturday, March 16, 2002 - 09:30 pm:

Discussionboard of FIGU » The Mission » Misc. Discussions on The Mission » Archive for 2001 - 2002

forum.figu.org/cgi-bin/us/discus.cgi

**Lehre der Propheten**Lehre der Wahrheit, Lehre des Geistes, Lehre des Lebens**von** Henoch, Elia, Jesaja, Jeremia, Jmmanuel,Muhammad und Billy (BEAM)**

http://billybooks.org/

Nokodemion Presentation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DM_H9y36Btw

WWW.FIGU.ORG http://theyfly.com/new-translation-talmud-jmmanuel http://www.figu.org/ch/files/downloads/buecher/figu-kelch_der_wahrheit_goblet-of-the-truth_v_20150307.pdf http://www.futureofmankind.info/Billy_Meier/The_Pleiadian/Plejaren_Contact_Reports https://creationaltruth.org/Library/FIGU-Books/Arahat-Athersata https://www.theyfly.com/articles-billy-eduard-albert-meier

Spreading of the Correct Peace Symbol https://creationaltruth.org/Portals/0/Images/Library/FIGU%20Stickers/Verbreitet%20das%20richtige%20Friedenssymbol-1.pdf

Ban-Srut Beam - Last Prophet - Line of Nokodemion

0 notes

Photo

Every religious belief system...is a complete blasphemy...in the eyes of every other religious belief system...and all are a complete blasphemy in the eyes of rational unbelief...

For example, as outlined by Atheist Ireland ...

“Here are the 25 blasphemous quotes that we first published on 1 January 2010, along with the quotation that has caused the Irish police to investigate Stephen Fry.

1. Jesus Christ, when asked if he was the son of God, in Matthew 26:64: “Thou hast said: nevertheless I say unto you, Hereafter shall ye see the Son of man sitting on the right hand of power, and coming in the clouds of heaven.” According to the Christian Bible, the Jewish chief priests and elders and council deemed this statement by Jesus to be blasphemous, and they sentenced Jesus to death for saying it.

2. Jesus Christ, talking to Jews about their God, in John 8:44: “Ye are of your father the devil, and the lusts of your father ye will do. He was a murderer from the beginning, and abode not in the truth, because there is no truth in him.” This is one of several chapters in the Christian Bible that can give a scriptural foundation to Christian anti-Semitism. The first part of John 8, the story of “whoever is without sin cast the first stone”, was not in the original version, but was added centuries later. The original John 8 is a debate between Jesus and some Jews. In brief, Jesus calls the Jews who disbelieve him sons of the Devil, the Jews try to stone him, and Jesus runs away and hides.

3. Muhammad, quoted in Hadith of Bukhari, Vol 1 Book 8 Hadith 427: “May Allah curse the Jews and Christians for they built the places of worship at the graves of their prophets.” This quote is attributed to Muhammad on his death-bed as a warning to Muslims not to copy this practice of the Jews and Christians. It is one of several passages in the Koran and in Hadith that can give a scriptural foundation to Islamic anti-Semitism, including the assertion in Sura 5:60 that Allah cursed Jews and turned some of them into apes and swine.

4. Mark Twain, describing the Christian Bible in Letters from the Earth, 1909: “Also it has another name – The Word of God. For the Christian thinks every word of it was dictated by God. It is full of interest. It has noble poetry in it; and some clever fables; and some blood-drenched history; and some good morals; and a wealth of obscenity; and upwards of a thousand lies… But you notice that when the Lord God of Heaven and Earth, adored Father of Man, goes to war, there is no limit. He is totally without mercy — he, who is called the Fountain of Mercy. He slays, slays, slays! All the men, all the beasts, all the boys, all the babies; also all the women and all the girls, except those that have not been deflowered. He makes no distinction between innocent and guilty… What the insane Father required was blood and misery; he was indifferent as to who furnished it.” Twain’s book was published posthumously in 1939. His daughter, Clara Clemens, at first objected to it being published, but later changed her mind in 1960 when she believed that public opinion had grown more tolerant of the expression of such ideas. That was half a century before Fianna Fail and the Green Party imposed a new blasphemy law on the people of Ireland.

5. Tom Lehrer, The Vatican Rag, 1963: “Get in line in that processional, step into that small confessional. There, the guy who’s got religion’ll tell you if your sin’s original. If it is, try playing it safer, drink the wine and chew the wafer. Two, four, six, eight, time to transubstantiate!”

6. Randy Newman, God’s Song, 1972: “And the Lord said: I burn down your cities – how blind you must be. I take from you your children, and you say how blessed are we. You all must be crazy to put your faith in me. That’s why I love mankind.”

7. James Kirkup, The Love That Dares to Speak its Name, 1976: “While they prepared the tomb I kept guard over him. His mother and the Magdalen had gone to fetch clean linen to shroud his nakedness. I was alone with him… I laid my lips around the tip of that great cock, the instrument of our salvation, our eternal joy. The shaft, still throbbed, anointed with death’s final ejaculation.” This extract is from a poem that led to the last successful blasphemy prosecution in Britain, when Denis Lemon was given a suspended prison sentence after he published it in the now-defunct magazine Gay News. In 2002, a public reading of the poem, on the steps of St. Martin-in-the-Fields church in Trafalgar Square, failed to lead to any prosecution. In 2008, the British Parliament abolished the common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel.

8. Matthias, son of Deuteronomy of Gath, in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, 1979: “Look, I had a lovely supper, and all I said to my wife was that piece of halibut was good enough for Jehovah.”

9. Rev Ian Paisley MEP to the Pope in the European Parliament, 1988: “I denounce you as the Antichrist.” Paisley’s website describes the Antichrist as being “a liar, the true son of the father of lies, the original liar from the beginning… he will imitate Christ, a diabolical imitation, Satan transformed into an angel of light, which will deceive the world.”

10. Conor Cruise O’Brien, 1989: “In the last century the Arab thinker Jamal al-Afghani wrote: ‘Every Muslim is sick and his only remedy is in the Koran.’ Unfortunately the sickness gets worse the more the remedy is taken.”

11. Frank Zappa, 1989: “If you want to get together in any exclusive situation and have people love you, fine – but to hang all this desperate sociology on the idea of The Cloud-Guy who has The Big Book, who knows if you’ve been bad or good – and cares about any of it – to hang it all on that, folks, is the chimpanzee part of the brain working.”

12. Salman Rushdie, 1990: “The idea of the sacred is quite simply one of the most conservative notions in any culture, because it seeks to turn other ideas – uncertainty, progress, change – into crimes.” In 1989, Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to kill Rushdie because of blasphemous passages in Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses.

13. Bjork, 1995: “I do not believe in religion, but if I had to choose one it would be Buddhism. It seems more livable, closer to men… I’ve been reading about reincarnation, and the Buddhists say we come back as animals and they refer to them as lesser beings. Well, animals aren’t lesser beings, they’re just like us. So I say fuck the Buddhists.”

14. Amanda Donohoe on her role in the Ken Russell movie Lair of the White Worm, 1995: “Spitting on Christ was a great deal of fun. I can’t embrace a male god who has persecuted female sexuality throughout the ages, and that persecution still goes on today all over the world.”

15. George Carlin, 1999: “Religion easily has the greatest bullshit story ever told. Think about it. Religion has actually convinced people that there’s an invisible man living in the sky who watches everything you do, every minute of every day. And the invisible man has a special list of ten things he does not want you to do. And if you do any of these ten things, he has a special place, full of fire and smoke and burning and torture and anguish, where he will send you to live and suffer and burn and choke and scream and cry forever and ever ’til the end of time! But He loves you. He loves you, and He needs money! He always needs money! He’s all-powerful, all-perfect, all-knowing, and all-wise, somehow just can’t handle money! Religion takes in billions of dollars, they pay no taxes, and they always need a little more. Now, talk about a good bullshit story. Holy Shit!”

16. Paul Woodfull as Ding Dong Denny O’Reilly, The Ballad of Jaysus Christ, 2000: “He said me ma’s a virgin and sure no one disagreed, Cause they knew a lad who walks on water’s handy with his feet… Jaysus oh Jaysus, as cool as bleedin’ ice, With all the scrubbers in Israel he could not be enticed, Jaysus oh Jaysus, it’s funny you never rode, Cause it’s you I do be shoutin’ for each time I shoot me load.”

17. Jesus Christ, in Jerry Springer The Opera, 2003: “Actually, I’m a bit gay.” In 2005, the Christian Institute tried to bring a prosecution against the BBC for screening Jerry Springer the Opera, but the UK courts refused to issue a summons.

18. Tim Minchin, Ten-foot Cock and a Few Hundred Virgins, 2005: “So you’re gonna live in paradise, With a ten-foot cock and a few hundred virgins, So you’re gonna sacrifice your life, For a shot at the greener grass, And when the Lord comes down with his shiny rod of judgment, He’s gonna kick my heathen ass.”

19. Richard Dawkins in The God Delusion, 2006: “The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully.” In 2007 Turkish publisher Erol Karaaslan was charged with the crime of insulting believers for publishing a Turkish translation of The God Delusion. He was acquitted in 2008, but another charge was brought in 2009. Karaaslan told the court that “it is a right to criticise religions and beliefs as part of the freedom of thought and expression.”

20. Pope Benedict XVI quoting a 14th century Byzantine emperor, 2006: “Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.” This statement has already led to both outrage and condemnation of the outrage. The Organisation of the Islamic Conference, the world’s largest Muslim body, said it was a “character assassination of the prophet Muhammad”. The Malaysian Prime Minister said that “the Pope must not take lightly the spread of outrage that has been created.” Pakistan’s foreign Ministry spokesperson said that “anyone who describes Islam as a religion as intolerant encourages violence”. The European Commission said that “reactions which are disproportionate and which are tantamount to rejecting freedom of speech are unacceptable.”

21. Christopher Hitchens in God is not Great, 2007: “There is some question as to whether Islam is a separate religion at all… Islam when examined is not much more than a rather obvious and ill-arranged set of plagiarisms, helping itself from earlier books and traditions as occasion appeared to require… It makes immense claims for itself, invokes prostrate submission or ‘surrender’ as a maxim to its adherents, and demands deference and respect from nonbelievers into the bargain. There is nothing—absolutely nothing—in its teachings that can even begin to justify such arrogance and presumption.”

22. Ian O’Doherty, 2009: “(If defamation of religion was illegal) it would be a crime for me to say that the notion of transubstantiation is so ridiculous that even a small child should be able to see the insanity and utter physical impossibility of a piece of bread and some wine somehow taking on corporeal form. It would be a crime for me to say that Islam is a backward desert superstition that has no place in modern, enlightened Europe and it would be a crime to point out that Jewish settlers in Israel who believe they have a God given right to take the land are, frankly, mad. All the above assertions will, no doubt, offend someone or other.”

23. Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, 2009: “Whether a person is atheist or any other, there is in fact in my view something not totally human if they leave out the transcendent… we call it God… I think that if you leave that out you are not fully human.” Because atheism is not a religion, the Irish blasphemy law does not protect atheists from abusive and insulting statements about their fundamental beliefs. While atheists are not seeking such protection, we include the statement here to point out that it is discriminatory that this law does not hold all citizens equal.

24. Dermot Ahern, Irish Minister for Justice, introducing his blasphemy law at an Oireachtas Justice Committee meeting, 2009, and referring to comments made about him personally: “They are blasphemous.” Deputy Pat Rabbitte replied: “Given the Minister’s self-image, it could very well be that we are blaspheming,” and Minister Ahern replied: “Deputy Rabbitte says that I am close to the baby Jesus, I am so pure.” So here we have an Irish Justice Minister joking about himself being blasphemed, at a parliamentary Justice Committee discussing his own blasphemy law, that could make his own jokes illegal.

25. As a bonus, Micheal Martin, Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, opposing attempts by Islamic States to make defamation of religion a crime at UN level, 2009: “We believe that the concept of defamation of religion is not consistent with the promotion and protection of human rights. It can be used to justify arbitrary limitations on, or the denial of, freedom of expression. Indeed, Ireland considers that freedom of expression is a key and inherent element in the manifestation of freedom of thought and conscience and as such is complementary to freedom of religion or belief.” Just months after Minister Martin made this comment, his colleague Dermot Ahern introduced Ireland’s new blasphemy law.

26. Finally, here is the quote that has caused the Irish police to investigate Stephen Fry for blasphemy. Asked by Gay Byrne on RTE what he would say if he was confronted by God, Fry replied: “How dare you create a world in which there is such misery that is not our fault. It’s not right. It’s utterly, utterly evil. Why should I respect a capricious, mean-minded, stupid God who creates a world which is so full of injustice and pain?” Questioned on how he would react if he was locked outside the pearly gates, he responded: “I would say, ‘Bone cancer in children? What’s that about?’ Because the God who created this universe, if it was created by God, is quite clearly a maniac, utter maniac. Totally selfish. We have to spend our life on our knees thanking him? What kind of God would do that?””

https://atheist.ie/2017/05/25-blasphemous-quotes-in-solidarity-with-stephen-fry/

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discuss the concept of gender justice in relation to qur’anic passages about rights and responsibilities of men and women

In this essay, I will be looking at the rights and responsibilities of men and women in accordance to Islam. To do so I will look at Qur’anic verses that are used in reference to the rights and responsibilities of women, and a variety of secondary sources. Asma Barlas identifies two key questions in relation to gender justice and the Qur’an, Does the Qur’an ‘condone sexual inequality or oppression’, or does it ‘permit and encourage liberation for women?’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 1)

Asma Barlas states that ‘a definition of patriarchy is fundamental to being able to establish the Qur’an as an antipatriarchal’, or a patriarchal, text. (Barlas, 2002, p. 12) and offers two definitions, a specific and a universal one. Barlas’ specific definition assumes that there is a real and a symbolic continuum between God, or Allah, and fathers. The specific definition has a father-right theory, which also extends to husband’s claim on his wife and children. The Qur’an was written in a society that functioned via this traditional form of patriarchy. The classical definition speaks of patriarchy in a historical sense, referring to a past culture and using it as an explanation for what may be contained in the Qur’an.

The broader definition that Barlas offers sees the Qur’an’s teachings as being universal. In this definition, the father rule has ‘reconstituted itself’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 12) into a political system which privileges males. This system operates off of three major claims, that ‘essential ontological and ethical-moral differences between women and men’, ‘these differences are a function of nature/biology’ and that the Qur’an’s different, unequal treatment of ‘women and men affirms their inherent inequality.’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 12) The broad patriarchal definition is more applicable to modern Islamic cultures.

It’s important to consider the political context before Islam was introduced. The description Daniel Brown gives of it make it seem rather grim for females, he points to things such as female infanticide being denounced ‘harshly and repeatedly’ (Brown, 2003, p. 26) and any woman who did survive to adulthood belonged to her father, only to later belong to her husband. Women had ‘no economic or social independence or rights’ (Brown, 2003, p. 26). Additionally, poetry at the time portrays women ‘primarily as sexual objects’ (Brown, 2003, p. 26), further diminishing any value women have that isn’t to serve men. The introduction of the Qur’an could actually be seen as quite beneficial, for women of the time, as it ‘not only repudiated female infanticide’ granting more of them a chance at actually surviving, ‘but gave women economic and legal status independent of their husbands and guaranteed daughters a share of inheritance’ (Brown, 2003, p. 26) so was a big step forwards, for the time. Cook notes that Khadija was an important and wealthy widow around the time Islam was introduced to the area, and she was powerful enough to employ Muhammad as her agent, and was the one to propose marriage to him. Cook points to Khadija as evidence that some pre-Islamic women did quite well for themselves, but this doesn’t mean that the society wasn’t completely horrific for women, it’s just a rare occurrence.

Asma Barlas, in response to her earlier question asking if the text is ‘sexist and misogynistic’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 1), presents evidence to support this view. For example, she references the Qur’an’s different treatment of women and men in regard to issues such as marriage, divorce and inheritance. Barlas places the blame for misogynistic readings of Islam on exegetes and commentators rather than the Qur’an’s teachings. In particular, Barlas points to the ‘Golden Age of Islam, which coincided with the Western Middle Ages’ as being a particularly ‘well known’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 9) time of misogyny, during this time many secondary texts were produced, these texts were influenced by men’s ‘own needs and experiences while either excluding or interpreting . . . women’s experiences.’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 9). The erasure of women’s experiences and voices in the secondary texts are often mistaken for a lack of representation in the text itself, and allows for a ‘striking consensus’ amongst Muslims when it comes to women’s issues.

Fatima Mernissi provides a similar approach, she focuses mainly on secondary texts, and claims that the misogynistic traditions sprout from either fabrications or a misunderstanding regarding the context of the Qur’anic verse. In particular, she singles out Abu Hurayra as being especially bad for fabricating, and claims that many intellectuals ‘sold themselves . . . to politicians who were trying to pressurise the collectors of religious knowledge to fabricate traditions that benefited them.’ (Mernissi, 1992, p. 45). She gives an example, the Qur’anic verse 33:53 which is often used to support the seclusion of women, ‘When you ask [his wives] for something, ask them from behind a partition.’ (Qur’an, 33:53), according to Mernissi the context for this is that the Prophet had just married, and needed personal space, and talking from behind a partition is likely a matter of respect. Mernissi rejects traditions which are contrary to her view under the belief that the Prophet had such a positive record in his treatment of women that any evidence to the contrary is not evidence at all. Daniel Brown criticises Mernissi for ignoring more problematic Quranic verses which contain clear patriarchal statements and instead focuses on Hadith. Mernissi’s thesis also implies that ‘Muslim community was able to completely depart from the spirit of the Prophet’s teaching remarkably short order’ (Daniel Brown 295), but this isn’t hard to believe considering that pre-Islamic Arabia was likely even more misogynistic than the misogynistic traditions Mernissi rejects.

Brown also looks at the approach of another Islamic feminist, Amina Wadud. Wadud takes the opposite approach to Mernissi, choosing to focus more on the Qur’an than on secondary texts like Hadith. Wadud takes on passages that seem to establish the superiority of men over women, like Quran 4:34, which states that ‘Men are the managers of the affairs of women for that God has preferred one of them over another.’ (Quran, 4:34) The interpretation Wadud takes from passages like these are that they represent a responsibility between men and women in society, and that they don’t represent men’s superiority over women. Further in the verse it gives instructions on how to punish a rebellious wife, ‘banish them to their couches and beat them.’ Wadud interprets this as ‘prohibiting unchecked violence’ (Wadud 76) against females, as it presents other punishments that are meant to be used before physical violence. This interpretation still permits physical violence against women, even if as a last resort, which a majority of modern views, especially western ones, would find inappropriate. Brown explains Wadud’s approach as restricting the meaning of passages with negative implications for women by saying they refer to specific contexts, and shouldn’t be universalised, however the Qur’an is the words of God, and ‘one cannot get much more universal than that’. (Brown 296)

One view that is pushed by Islamic feminists, is that the Qur’an may actually ‘permit and encourage liberation for women’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 1), as mentioned previously various commentators believe that the Qur’an has been misinterpreted to enforce patriarchal beliefs, but the Qur’an ‘can be read in multiple modes’. Muslim theology makes a distinction between divine speech and the earthly realisation, to avoid ‘collapsing God’s Words with our interpretations of those Words’ (Barlas, 2002, p. 10), this view can be supported with a verse in the Qur’an which warns against confusing the words of the Qur’an with those of readings of it. There are some parts of the Qur’an which can be hard to blame on readings or certain interpretations, for example the verse mentioned earlier clearly permits beating someone’s wife.