#Monumenta Germaniae

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alessandria cambia data di nascita: ora è ufficiale, fondata il 23 aprile 1168

La storia di Alessandria si arricchisce di un nuovo capitolo: la data della sua fondazione cambia ufficialmente e viene fissata al 23 aprile 1168, giorno di San Giorgio.

La storia di Alessandria si arricchisce di un nuovo capitolo: la data della sua fondazione cambia ufficialmente e viene fissata al 23 aprile 1168, giorno di San Giorgio. L’annuncio è stato dato ieri dal professor Paolo Grillo, ordinario dell’Università di Milano, durante il convegno “Fondare una Città, fondare una Chiesa. Alle origini di Alessandria”, organizzato nell’ambito delle celebrazioni…

#850 anni Diocesi Alessandria#Alessandria 23 aprile 1168#Alessandria e la sua identità storica.#Alessandria nel Medioevo#Alessandria today#analisi fonti storiche#Annales Cremonenses#Barbarossa e Lega Lombarda#cambiamenti celebrazioni Alessandria#cambio data storica Alessandria#città storiche del Piemonte#Civitas Nova#consoli di Alessandria#convegno fondazione Alessandria#Cremona e Lega Lombarda#cultura e tradizione storica Alessandria#documenti medievali#eventi storici in Piemonte#Google News#italianewsmedia.com#medioevo italiano#Monumenta Germaniae#Monumenta Germaniae Historica#municipi medievali#nascita di Alessandria#nuova data fondazione Alessandria#nuove interpretazioni storiche#nuove scoperte storiche#Papa Alessandro III#Pier Carlo Lava

0 notes

Text

Seventy-five years ago, in February 1945, during the Second World War, Allied forces bombed the magnificent baroque city of Dresden, Germany, destroying most of it and killing thousands of civilians.

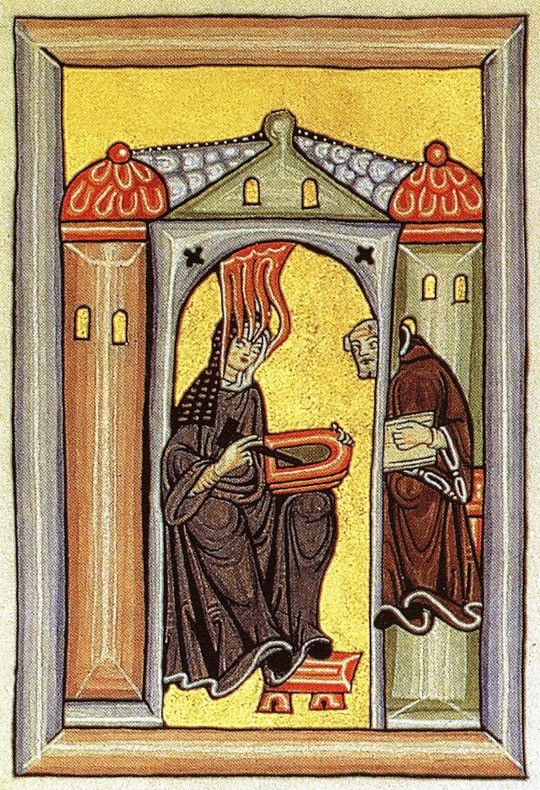

In central Dresden, however, a bank vault holding two precious medieval manuscripts survived the resulting inferno unscathed. The manuscripts were the works of the prolific 12th-century composer, writer and visionary, St. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), who had established a convent on the Rhine River, near Wiesbaden and 500 kilometres west of Dresden.Hildegard Abbey, near Wiesbaden, Germany. (Kate Helsen), Author provided

Hildegard, whose writings documented her religious visions, including a theology of the feminine and an ecological consciousness, and who practised medicinal herbology, was venerated locally as a saint for centuries. The Catholic Church only recently recognized her as one, and also designated her a Doctor of the Church.

After the Dresden bombings, the Soviet Army seized and inspected the surviving vault. The first bank official to enter the vault afterwards found it pillaged, with only one manuscript remaining. The bank could never confirm if the vault was emptied in an official capacity or if it was plundered.

The missing manuscript has not been seen in the West since. The other made its way back to its original home of Wiesbaden, on the other side of Germany, through the extraordinary efforts of two women.

This is the story of how those women conspired to return the manuscript home.

The librarian

In 1942, Gustav Struck, the director of the state library in Wiesbaden, became worried about local air raids. Following many European institutions, he decided that his library’s manuscripts needed to be sent elsewhere for safe keeping.

Two of the library’s most valuable possessions were manuscripts of Hildegard’s works. One was a beautifully illuminated copy of Scivias, a collection of 26 religious visions. The other manuscript, known as the Riesencodex, is the most complete compilation of her works, including the visionary writings, letters and the largest known collection of her music.

Why Struck chose to store the manuscripts in a bank vault in Dresden is still a mystery, but their journey there by train and streetcar mid-war is thoroughly documented.

The manuscripts sat in the bank vault for three years until the attack on Dresden.

After the war

Immediately after the war, the Americans sacked Struck in their denazification efforts. Librarian Franz Götting took over his job.

Götting inquired about the manuscripts as soon as mail service to Dresden resumed, and learned that the Scivias manuscript was missing, either seized or plundered, but that the bank still had the Riesencodex.

Götting asked repeatedly for the Riesencodex to be returned from Dresden to Wiesbaden. The difficulty was that Dresden was in the newly formed Soviet zone, while Wiesbaden was in the American zone. (The Allies had divided Germany into four occupation zones, and similarly divided Germany’s capital city, Berlin, into four sectors.) The Soviets had issued a decree stating that all property found in German territory occupied by the Red Army now belonged to them.Hildegard’s composition ‘O Most Noble Greenness.’

The plan

A scholar and medievalist in Berlin, however, came up with a scheme to retrieve the manuscript. Margarethe Kühn, a devout Catholic who expressed a great love for Hildegard, held a position as a researcher and editor with the Monumenta Germaniae Historica project. After the war she found herself living in the American sector of Berlin and working in the Soviet sector.Photograph of the 12th-century ‘Risencodex’ manuscript. (Wikimedia/Landesbibliothek Wiesbaden), CC BY

Kühn had stayed at the Hildegard Abbey for several days in March 1947 and had even explored joining the Abbey as a nun herself. She must have heard while she was there that the Riesencodex was being held in Dresden without any promise of return. She devised a plan to help.

Kühn asked Götting for permission to borrow the manuscript for study purposes. Götting asked the Soviet-run Ministry for Education, University and Science in Dresden on Kühn’s behalf. Much to the librarian’s surprise, ministry officials agreed to send the manuscript for Kühn to examine at the German Academy, a national research institute established in 1946 in Berlin by the Soviet administration.

Kühn was convinced that the bureaucrats in Dresden would not recognize the Riesencodex. She decided that when returning the manuscript, with help from the Wiesbaden librarian, Götting, she would send a substitute manuscript to Dresden, and the original to Wiesbaden.

The crossing

Kühn enacted the plan with the help of an American woman, Caroline Walsh.

How exactly Kühn and Walsh met is not known, but Caroline’s husband Robert Walsh was in the American air force and was stationed in Berlin as the director of intelligence for the European command from 1947-48.

In an interview in 1984, Robert explained that when he and Caroline were in Berlin she had “worked a great deal with the Germans and with the religious outfits over there, too.” Since the Walshes were also Catholic, it is likely that they and Kühn met through Catholic circles in the city.

Caroline’s position as the wife of a high-ranking military officer may have made it easier for her to travel across military occupation zones and sectors.

In any case, we know that Caroline travelled by train and car and delivered the manuscript in person to the Hildegard Abbey in Eibingen on March 11, 1948. The nuns notified Götting at the Wiesbaden library and returned the manuscript.

The swap

A Scivias illumination on an edition of Hildegard’s medical works. Beuroner Kunstverlag

Götting, meanwhile, had not found a suitably sized manuscript to stand in for the large Riesencodex to trick the Soviets. He instead selected a 15th-century printed book of a similar size and had sent this to Kühn in Berlin.

It took some time for Kühn to deliver it to the Ministry for Education, University and Science in Dresden, and two further months before anyone there opened the package in January 1950. By that time, Hildegard’s manuscript was safely in Wiesbaden. But officials spotted the deception and Kühn was in trouble.

An official in Dresden wrote to the German Academy in Berlin demanding to know why they had been sent a printed book rather than the Riesencodex manuscript.

Kühn’s boss, Fritz Rörig, who received the letter was furious with her. Rörig and Götting smoothed things over with Dresden by offering another manuscript in exchange. But Rörig told Kühn that the East German police were inquiring about her, the implication being that he had reported her.

One still missing

Although she remained deeply worried for some time afterwards, Kühn never lost her job at the Monumenta nor was she arrested, despite Rörig’s threats. For the rest of her life she maintained a rare cross-border existence, living on Soviet wages in the American sector while continuing at the same job until her death in 1986, at the age of 92.

As one of many scholars who regularly consults the Riesencodex, now available online, I am enormously grateful to Caroline Walsh, and particularly to Kühn who risked her livelihood for the sake of a book.

I am not alone, however, in hoping that during my lifetime someone, somewhere will find the pilfered Scivias manuscript and return it as well.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to Vita S. Bathildis, Balthild was born circa 626–627. She was beautiful, intelligent, modest and attentive to the needs of others. Balthild was sold into slavery as a young girl and served in the household of Erchinoald, the mayor of the palace of Neustria to Clovis. Erchinoald, whose wife had died, was attracted to Balthild and wanted to marry her, but she did not want to marry him. She hid herself away and waited until Erchinoald had remarried. Later, possibly because of Erchinoald, Clovis noticed her and asked for her hand in marriage.

Even as queen, Balthild remained humble and modest. She is famous for her charitable service and generous donations. From her donations, the abbeys of Corbie and Chelleswere founded; it is likely that others such as Jumièges, Jouarre and Luxeuil were also founded by the queen. She provided support for Saint Claudius of Besançon and his abbey in the Jura Mountains.

Balthild bore Clovis three children, all of whom became kings: Clotaire, Childeric and Theuderic.

When Clovis died (between 655 and 658), his eldest son Clotaire succeeded to the throne. His mother Balthild acted as the queen regent. As queen, she was a capable stateswoman. She abolished the practice of trading Christian slaves and strove to free children who had been sold into slavery. This claim is corroborated by Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg, who mentions that Balthild and Saint Eloi “worked together on their favorite charity, the buying and freeing of slaves”. After her three sons reached adulthood and had become established in their respective territories (Clotaire in Neustria, Childeric in Austrasia, and Theuderic in Burgundy), Balthild withdrew to her favourite Abbey of Chelles near Paris.

Balthild died on 30 January 680 and was buried at the Abbey of Chelles, east of Paris. Her Vita was written soon after her death, probably by one of the community of Chelles. The Vita Baldechildis/Vita Bathildis reginae Francorum in Monumenta Germania Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovincarum, as with most of the vitae of royal Merovingian-era saints, provides some useful details for the historian.

#saint balthild#balthilda#balthild of ascany#balthild of ascania#merovingian#french history#frankish#clovis ii#historical#history#history edit#history edits#edit#emma booth

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Quest for Fredegund [1]

So folks, welcome to a long post that I would dedicate to the wonderfull regina Fredegund. I’m aware that there is already a large part of fiction and biographies which have been made on her (at least in french, not sure for the english part), but all of that is actually quite of lame and/or false on many assumptions. Truth is that Fredegund is a member of a large group of misogynistic historical characters and that she is often made used for depicting some weird fantasies for historians.

She is the evil pagan witch, the murderous, the bloodthirsty woman who wraps men around her finger and made use of violence to reach her goals. She is also a voracious sexual monster, using lovers again and again. She kills, she burns, she steals, and even makes her stepdaughter gang-raped for her own revenge.

She is the DEVIL!

Drawing by Alessia de Vincenzi for the comics Fredegund, the Bloodthirsty

But, you know what, folks? I came to become very cautious with years: when a man tells me “here, this is a vicious woman” and when an mid-50yo lady takes the man’s statement litteraly and explains to me why that same woman was vicious, gives her reasons to do that and finally claims that she was right to do all these things (you know, the murders, the gang-rape...), I kinda want to search on my own and see by my eyes only.

So, let’s go on a quest, the Quest for Fredegund. All my sources will be referenced, with links when I can (for example, I have the Fredegar’s Chronica only in scans on my PC). Most of the original texts are also on the MGH, the Monumenta Germaniae Historica.

Here are some of the sources where you can find informations on her:

Gregorius Turonensis, Decem Libri Historiarum

Fredegar, Chronica

Venantius Fortunatus, Carmina

So... let’s begin!

What do we really know about Fredegund?

Truth is, not so much after all. At least, not so much about her personal background. For people who are not yet accustomed with her:

She is the third chief wife of King (but I prefer using the word “rex”) Chilperich I, one of the three leaders of the Gauls in the second half of the 6th century.

Her birth is unknown, and she died in 597 as the mother of Chilperich’s successor, Chlothacar II.

She gave birth to 6 children in total, including 5 sons, which means she’s actually one of the reginae who had the most children known during the period. Their names are:

Chlodobert († 580)

Rigund († ?)

Samson († 577)

Dagobert († 580)

Theodorich († 583)

Chlothacar II († 629)

There is actually no representation of her and no description of her looks, but people assume very often that she was a beauty and made her a bloody sex-symbol of the Early Middle Ages (yikes...)

When does Fredegund appear for the first time?

The first mention of Fredegund that we have is actually a short mention in Gregorius of Tours’ chronicle, Decem Libri Historiarum (aka History of the Franks).

In DLH, IV, 28 (x), Gregorius described how in 567 Chilperich got engaged to Galswintha, daughter of Athanagild and, in order to gain her hand, had to dismiss all his “ uxores / wives”.

King Chilperic sent to ask for the hand of Galswinth, the sister of Brunhild, although he already had a number of wives. He told the messengers to say that he promised to dismiss all the others, if only he were considered worthy of marrying a King’s daughter of a rank equal to his own.

Still no mention of Fredegund at that moment, just that Chilperich had a certain amont of unnamed women around him. The only who appeared of the whole is Audovera, mother of 4 children, including 3 sons, Theodebert, Merovech and Chlodovech.

Chilperic had three sons by one of his earlier consorts, Audovera: these were Theudebert, about whom I have told you already, Merovech and Clovis.

The first time she is named is later on the text: at that moment, Chilperich got married with Galswintha, but their relationship tend to became difficult months passing, and Gregorius implied that it was because of the presence of Fredegund.

A great quarrel soon ensued between the two of them, however, because he also loved Fredegund, whom he had married before he married Galswinth.

Fredegund is so introduced as a precedent concubine/wife of the rex (depend of the people and how they see her actually). None is said about her life before that year 567/568, apart that Chilperich seems really infatuated to her.

So, was Fredegund really a slave?

Technically, yes and no. Yes, because we have some hints that could lead us to think of it, and no because finally it’s just hints and not reals informations.

First mention is: in DLH, IX, 34 (x), Fredegund had according to Gregorius of Tours a big quarrel with her daughter Rigund and as they were arguing against each other, Rigund threathened her mother to “servitio redeberit / revert to her original rank of serving-woman”

Rigunth, Chilperic’s daughter, was always attacking her mother (Fredegund), and saying that she herself was the real mistress, whereas her mother ought to revert to her original rank of serving-woman. She would often insult her mother to her face, and they frequently exchanged slaps and punches.

Second mention is actually a mention in a later-one abbey’s chronicle, called The Chronicle of Saint-Vaast of Arras (x), in which the author says that Fredegund was born in this place (Angicourt, in the Oise department) and that her parents belong to the villa, and so were perhaps slaves.

Haec ex territorio Belvacensi nata est de familia atque sancti Vedasti villa Vunguscurht, quam, ut praetulimus, Lotharius rex dederat nostro patrono.

But that mention should be taken with precaution as the chronicle was written during the 11th century and as religious chronicles are often full of false stories and approximations: the meaning behind the redaction is not to write facts, but to justify of the longevity of a foundation and of its links with well-known protectors, and the most ancient, the better for that!

Third mention: in the Liber Historiae Francorum, a major compilation of the Decem Libri Historiae, the Fredegar’s Chronica and some made-up characters and facts, Fredegund is introduced as “ex familia infima” (LHF, 31), and, most important, as the maid of Audovera, first chief wife of Chilperich.

That’s in fact all of we know. It is also true that Fredegund did not seem to have any significant relatives, father, brother, even uncle... but it was also the same for several others reginae, so I’m not convinced that it could means something about her social background.

Now, if we talk about fiction and theories, I really like the possibility that she may have been a slave, and if you ask me to write a fictional story about her, my favorite theory would be that she was a weaver slave, some kind of skilled embroiderer girl before becoming a concubine of the rex, but it��s just FICTION, not FACTS.

Last thing about that matter, scholars often think down of her background because of her name:

“Fredegund” is composed of the terms Fried / “peace” | Gund / “war”, meaning litteraly “war and peace”, which sounds funny to scholars.

Still during the 6th century, Franks had the habit to create names for children by mixing parts of the parents’ names (e.g. in Rigund : Rich from ChilpeRICH and Gund from FredeGUND), so the theory is that she was born from low-rank, perhaps slaves, parents who were not aware of the subtility of such creation and so created a strange name for their daughter... (I guess these scholars never heard of a name like “North West”, that must be it...)

But, was not Fredegund Audovera’s maid/servant?

Most historians and writers indeed say that Fredegund was actually Audovera’s maid before her own elevation as mother of Chilperich’s children and chief wife. But as we had seen it before (DLH, IV, 28), none of the sources say that: Fredegund is only said to be "married [to Chilperich] before he married Galswinth” and Audovera is designated as “one of his earlier consorts” even not the only one.

So where does that story come from? Once again, from the Liber Historiae Francorum... In LHF, 31, the unnamed author tells a story about how Audovera have been evicted from the royal palace, based only on Fredegund’s trickery. Alone and pregnant while her husband was away at war, Audovera just had given birth to a little girl that she named Childesinda, or for some autors Basina.

On Fredegund’s suggestion, a baptism was prepared before the return of the father, but at the beginning of the ceremony, the lady who would have been the godmother of the princess was still missing. She so persuaded her mistress Audovera to hold herself her infant daughter, whithout saying to her that by doing that, she would become de facto the godmother of her own daughter. However, a canon law strictly forbidding marriage between parents and godparents, Audovera was convicted of incest and kicked from the palace.

The problem with this whole story is not only that it is a complete invention, written long time after the real events, but most importantly, that the taboo forbidding marriages with godparents was in fact officially voted in the Council in Trullo, held in 692, which means 130 years after Fredegund and Audovera possible hostility! But because this is an undeniable dramatic storyline, writers and historians are really unwilling to abandon it and continue to spread it...

[Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3]

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studying made me realise how much I’d like to live in an English-speaking country.

No gendering.

No Monumenta Germaniae Historica.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Sanctus amor patriae dat animum

Wahlspruch der Monumenta Germaniae Historica

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Albert Theodor Johann Karl Ferdinand Brackmann (24 June 1871, Hanover – 17 March 1952, Berlin-Dahlem)[1] was a leading nationalist German historian associated with the Ostforschung, a multi-disciplined organisation set up to co-ordinate German propaganda on Eastern Europe. After Nazis were elected to power, he became one of the chief propagandists in service of the regime. In this position he supported Nazi genocidal policies, ethnic cleansing and anti-semitism.

At the conclusion of his university education in Tübingen, Leipzig, and Göttingen, Brackmann joined, at the age of twenty-seven, the staff of MGH (Monumenta Germaniae Historica),[2] the leading German source publication for medieval documents. He was appointed professor of history at Königsberg in 1913, Marburg in 1920, and Berlin in 1922.[1] In 1929 he became the director general of the Prussian Privy State Archives, in Berlin-Dahlem.[3] In connection with accepting the position he advocated for the establishment of a special Institute for Archival Sciences and Historical Training (Preußisches Institut für Archivwissenschaft), to provide for the professional training of archivists; the institute, which came under the administration of the state archives, opened in Berlin-Dahlem in May 1930.[3][4] Brackmann, in his capacity as director general of the archives, simultaneously served as the archival institute's first director, until his retirement in 1936.[5] During his term at the archives he retained an honorary professorship at the University of Berlin.[2]

Originally a specialist in relations between the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy, he turned towards the history of the Germans in Eastern Europe as a result of his experiences of the First World War.[2] Politically right-wing, he was a member first of the DVP (German People's Party) and then of the DNVP (German National People's Party) during the Weimar Republic,[6] and was joint editor of the prestigious and influential Historische Zeitschrift from 1928 to 1935.[2]

Favoured by leading Nazis, including Adolf Hitler himself, Brackmann steadily turned the Ostforschung away from detached academic work towards projects that fed directly into the wider foreign policy and expansionist aims being pursued by the Nazi government. In September 1939, he congratulated himself on heading a research organisation that had become the central agency "for scholarly advice for the Foreign, Interior and Propaganda ministries, the army high command and a number of SS departments."[7][8] He was also an author for the Ahnenerbe, a research body set up under the auspices of Heinrich Himmler, publishing a booklet entitled "Crisis and Construction in Eastern Europe"[9] that questioned the historical validity of Poland as a nation by arguing that Mitteleuropa (Central Europe) was the original Lebensraum of the German nation.[10]

After the outbreak of World War II, Brackmann's work also extended to issues of Germanisation, and the removal of "undesired ethnic elements" from German domains. In this particular context he did much to promote the work of Otto Reche, professor of racial studies at the University of Leipzig, and a noted anti-Semite. Responding to Reche's appeal that Germany needed Raum (room), and not "Polish lice in the fur", Brackmann brought his argument for a strict definition of ethnicity to the attention of a number of different ministries. In essence, Reche argued that the Poles should be pushed eastwards further into Ukraine, whose population, in turn, would be pushed even further east.

Defeat in the war produced only a temporary halt in Brackmann's academic work. In 1946 he was actively involved in the reconstruction of Ostforschung, and many of his pupils went on to occupy important academic positions in the German Federal Republic, with anti-communism replacing the former fashion for expansionism. Brackmann died in 1952, but the Zeitschrift für Ostforschung went on, amongst other things, to re-publish some of the work of the notoriously anti-Polish Dr Kurt Lück, who served as an SS-Sonderführer, before he was killed by Soviet partisans in 1942.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Brackmann

0 notes

Quote

Pectus amor nostrum penetravit flamma... Atque calore novo semper inardet amor. Nec mare, nec tellus, montes nec silva vel alpes Huic obstare queunt aut inhibere viam, Quo minus, alme pater, semper tua viscera lingat, Vel lacrimis lavet pectus, amate, tuum. ... Omnia tristifico mutantur gaudia luctu, Nil est perpetuum, cuncta perire queunt. Te modo quapropter fugiamus pectore toto, Tuque et nos, mundus iam periture, fugis...

Alcuin (~782-800 AD), in John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality, University of Chicago Press, 1980 (Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Poetae, I, p. 236)

0 notes

Text

The American Archivist, 1946

There is, furthermore, the important consideration that scholarly institutions such as the Institute for Archival Science, the Monumenta Germaniae, the Emperor William Institute for German History, the Hanseatic Historical Society, the Central Research Center for Post War History, and the University Seminar for Regional History have stored their collections of material, their working papers, and other manuscripts in the mines together with the archival holdings. Now that the war is over they would like to have them back in order to continue their work, particularly since getting this material back is also a matter of existence for them. You know that a part of the materials has been collected over many decades and that they constitute an intellectual product that belongs not to Germany alone but to Western civilization in its entirety. Its destruction or even its eventual removal by the Russians would mean an inconceivable loss for our Western intellectual life.

0 notes

Text

Monastische Gelehrsamkeit

... Tremp widmet sich den historischen Forschungen der St. Galler Konventualen, für die Jean Mabillon als Motivator wirkte, in denen er aber zugleich auch Geistverwandte fand, die ihr Kloster in ein Forschungszentrum verwandelten, aus denen später die Monumenta Germaniae Historica hervorgingen. from Google Alert – Kloster http://ift.tt/2jbUuhD via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Milyen volt Attila?

Maga Attila Mundzuc nevű atyától született, testvérei voltak Octar és Roas, kikről azt beszélik, hogy már Attila előtt övék volt az ország. De mégsem annyi, mint amennyi később az övé lett. Haláluk után Bleda (Buda) nevű testvérével együtt követte őket a hunok királyságában. Hogy pedig jó reménnyel induljon ama hadjáratra, melyre készülődött, erejének fokozását rokongyilkossággal igyekezett elérni, valamennyi hozzátartozójának megöletésével törekedvén a döntésre. Ugyanis testvérének, Bledának csalárd meggyilkolása után, ki a hunok nagy része fölött uralkodott, az egész népet egyesítette, és más, akkor uralma alá tartozó népeknek is nagyszámú seregét egybegyűjtve, a világ első népeinek, a rómaiaknak és a vízigótoknak leigázására indult. Azt beszélik, hogy serege ötszázezer emberből állt. Ez a férfiú azért született e világra, hogy a népek megremegjenek. Minden földeknek félelme volt, ki, nem tudom, mi módon, mindeneket rémületbe ejtett, szárnyra kelt félelmetes hírével. Mert büszke megjelenésű volt, ide-oda jártatta szemeit, úgy, hogy e fennhéjázó embernek már teste mozdulatai is kitüntették hatalmát. Szerette ugyan a hadakozást, de mégis mérsékelte magát; megfontoltsága hatalmas, a könyörgésre hallgatott és kegyesen bánt azokkal, kiket egyszer már bizalmába fogadott. Kis termetű volt, széles mellű, feje nagy formájú. Ritkás szakállával, apró szemével, lapos orrával, barna bőrével származásának jegyeit viselte magán. És ámbár olyan természete volt, hogy mindig is elbizakodott, önbizalmát még növelte Mars kardjának megtalálása, melyet a szkíta királyok mindig szent dolognak tartottak. Priscus történetíró elmondja, hogy mily alkalommal találták meg. Midőn egy pásztor - úgymond - észrevette, hogy nyájának egyik tinója sántít, de a sebnek okát nem lelte, a vérnyomokat gondosan követte, és így jutott el a kardhoz, melybe a füveket legelő állat vigyázatlanul belelépett. Kiásta, és azonnal Attilához vitte. Ez, minthogy bőkezű volt, ajándékokkal örvendeztette meg, mert úgy vélte, hogy az egész világ fejedelme lett, és Mars kardjával hatalmat nyert a hadak felett

Iordanes: De origine actibusque Getarum. Kiadása: Monumenta Germaniae. Historica, Auctores Antiquissimi, V. kötet In. Mezey László - Róma utódai. Budapest 1986. pp. 30-31.

0 notes