#Mendocino Project

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Walk Softly And . . . Why Some Solution Providers Are Going To Survive And Thrive Beyond 2025

Finally, a solution provider shows me an actual demo of their platform!

EDITOR’S NOTE: Before reading today’s post, please do so now if you haven’t read the previous post—Finally, No GenAI Hocus Pocus (A new DUET?)—because it will provide the needed context regarding today’s blog entry. I recently asked ChatGPT the following questions, to which I received the following answers: When did Zycus introduce Merlin? Zycus introduced Merlin AI Suite in 2019. Merlin is an…

#@SAP#AI#Duet#genai#Mendocino Project#Merlin#Microsoft#procurement#procuretech#supply chain#technology#Zycus

0 notes

Text

MLT will begin work this month as it coordinates a team of experts to bolster the population of the Behren’s Silverspot butterfly, a federally endangered species. In December, the Wildlife Conservation Board awarded MLT a $1.5 million dollar grant to work with State Parks, the Bureau of Land Management, the Laguna Foundation, the Sequoia Park Zoo, and Wynn Coastal Planning & Biology. This joint, team-effort will oversee a multi-stage, four-year plan to help this butterfly, once a common sight on the Northern California coast.

The restoration will collectively cover 53 acres.

—

The first phase of this project entails habitat restoration. Paid staff and volunteers from these agencies will remove invasive plant species in three different North Coast locations, and then plant more than 35,000 native plants reared in nurseries. These native species will include a mix of native grasses, early blue violets, and other nectar species.

The focus of this effort is in multiple sites. The number of native species to be replanted varies from site-to-site and includes planting seeds at some locations as well as using controlled grazing to eliminate invasive plants in others.

This plant-restoration effort will continue for several years.

In addition to habitat restoration, the grant will fund a two-year program of captive rearing of the butterflies. Experts from the Sequoia Zoo will collect female butterflies from the wild in late summer and the butterflies’ eggs will be hatched in a protected environment. The caterpillars will be raised to the pupae stage.

Then, the following summer, 50-200 butterflies will be released into the improved habitat. Their numbers will be monitored each season for three years thereafter.

#good news#science#environmentalism#nature#environment#conservation#butterflies#endangered species#restoration

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. Ida Louise Jackson (October 12, 1902 – March 8, 1996) was an educator and philanthropist. She graduated from the UC Berkeley. As one of 17 African American students, she prioritized creating safe spaces for African American community members. She was invested in a teaching career, specifically in Oakland. She became the first African American woman to teach high school in the state of California. Her ambitions were rooted in giving back to her community in Mississippi. She returned to her home state in 1935 to develop programs around education and health care for poor, rural African Americans. Her contributions were celebrated by UC Berkeley, which named their first graduate apartment housing unit in her honor.

She was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi. She was the daughter of Pompey Jackson and Nellie Jackson. Her father was a pastor and farmer. Her mother was born in New Orleans. She was one of eight children but was the youngest child and their only girl.

She worked to bring the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority to campus. She co-founded the Rho Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority. She earned a BA in Education, Vocational Guidance, and Counseling. She applied for a teaching position in the Oakland Public Schools, only to be told by the administration that she was still not qualified. She earned an MA from UC Berkeley.

She furthered her studies at Columbia University pursuing an Ed.D. She returned to Berkeley to seek the Administrative Credential to be certified by the State of California as a School Administrator. By 1936, she was certified.

In 1934, She became the national Alpha Kappa Alpha president. She co-founded and became general director of the Mississippi Health Project. She served as the Dean of Women at the Tuskegee Institute (1937-38). She was involved in the NAACP, the YWCA, and the National Council of Negro Women. She returned to McClymonds High School where she taught until her retirement in 1953. She transitioned to running her family’s sheep ranch in Mendocino County. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #alphakappaalpha

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

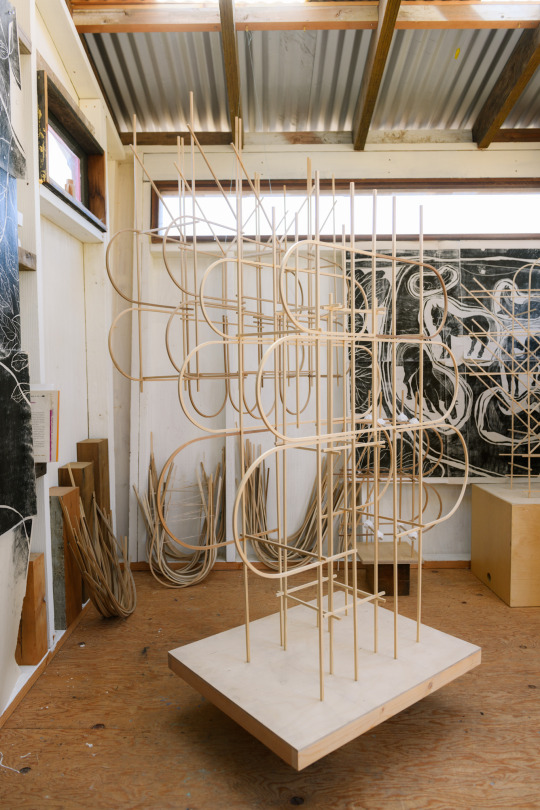

Artist Spotlight: John Gnorski

When we asked John Gnorski what on earth are EARTH BABIES, he took us on a subterranean journey to meet them. Or at least that's how it felt. Hearing John speak about his creative process certainly takes you all over, even into your subconsciousness, about which he has a lot to say. His art is full of strange landscapes, strange portraits, strange figures. Our current fave is one from his Clouds Roll By Like A Train In The Sky series not because of its great title, or because the clouds might actually be birds or blossoms, but because peeking through the print's ink is the grain of the woodblock, reminding us of the materiality that grounds all our work, no matter how wildly dreamt.

Studio AHEAD: John, your bio is mysteriously pithy: “Born in Alexandria, Virginia, living/ working in Point Reyes Station, CA.” What brought you to the other side of the country?

John Gnorski: I moved from the East Coast more or less on a whim in 2007, picking up and leaving the Hudson Valley, which had been my home for 6 years at that point, and ending up in Portland, OR. Luckily it was still a pretty affordable town at the time so I was able to piece together a nice existence doing carpentry for a day job (which would indelibly inform my art practice) and making art and music every other waking hour. I found a great community, fell in love with the truly epic landscape of the West, and at some point the West Coast just became home.

After many happy years up in Oregon, my partner Katie, who is a filmmaker, decided to get a master’s degree and that instigated our (truly auspicious) move to the Bay. One thing led to another, and we were lucky enough to find a house to rent in Pt. Reyes Station. Before long we found a great community out here and we hope to stay for as long as we can.

I do miss the East sometimes, especially the sort of archetypal procession of seasons there with crisp autumn days, deep winters, and summer thunderstorms and lighting bugs. That said, I can’t imagine a more beautiful place to live than here on the Northern California coast. I’m grateful every day to be here and I often think to myself how did I even end up here in this incredible place?

Studio AHEAD: Has Northern California come to influence the materiality of your work?

John Gnorski: Absolutely. In a very literal sense I tend to use native wood in my work whenever I can, but the influence goes beyond the physical material to a particular sensibility that seems to be shared by a lot of Northern California artists across generations and styles. I find that, at least in my experience, there’s less concern out here about the whole (false) binary of art vs. craft than I experienced as a young artist on the East Coast (particularly in the vicinity of New York).

I think that this attitude has, thankfully, changed quite a bit pretty much everywhere in the years since I moved west, but nevertheless California has a long history of breaking down established conventions and categories. Ceramics and wood sculpture, for instance, have been taken seriously out here for generations in a way that hasn’t historically been the case out east.

This anti-hierarchical spirit famously permeates a lot of the culture out here. A nice example is the great DIY building tradition of the “hippies” and other folks who took to the rural areas of the coast, starting in the middle of the last century, and made truly beautiful, strange, and inspired homes out here that flout both architectural convention and often the laws of physics. I’ve had the pleasure of helping to restore some buildings like this up in Mendocino and, to bring this full circle, some of the little scraps and bits I’ve taken with me from those projects have become pieces of my own work, along with the lessons of those often anonymous artist/builders who made, intentionally or not, amazing sculpture-houses.

There’s also a very strong Japanese influence on the aesthetics of so much California art/craft/design that’s found its way into my work. Would I be making these very Japanese/Noguchi-inspired lanterns if I hadn’t ended up here? I don’t know for sure but I’m guessing this place has informed them quite a bit.

Studio AHEAD: Don't get Homan started on Noguchi. He's obsessed. What is your relation to abstraction? Many of your sculptures and drawings almost seem to form recognizable figures, but not quite.

John Gnorski: With very few exceptions everything I make is representational even if it’s hard to decipher the image in the finished piece. I’m looking at a little watercolor painting right now that would almost certainly appear totally abstract to anyone but me, but I know that I made it in the Mojave desert and I can see the particular landscape that I was trying to depict—the horizon, the heat ripples, little constellations of scrubby desert plants—though it’s basically reduced to visual symbols.

It’s not necessarily a formal decision I’ve made to avoid pure abstraction, it’s more of a narrative one. Having concrete subject matter is an important starting point for me, one method of avoiding the potentially paralyzing experience of confronting the blank page. So even if the finished picture or object ends up miles away from where it began, I still start by saying to myself, for instance: I’m going to draw a lizard sunning itself on a stump or, as in one of the pictures I’m working on now, I’m going to draw a bather in Tomales Bay stooping down to look at a bat ray. One might end up a pretty faithful manifestation of the concept while another might go through the ringer of some process and turn out as a loopy line drawing that barely hints at its source material.

I sometimes do the same thing when I write songs, coming up with a title first and then writing into that. The two even intersect as in my continuing series of cloud pictures all of which are titled “Clouds Roll By Like A Train In The Sky” which is also the name of a song I wrote. Without the title those pictures read as geometric abstraction, but with the title they become clouds. Context is so important!

Studio AHEAD: Those cloud pictures, and also your Rorschach-like quarantine notebooks/bird and butterfly prints, give room to the subconscious. How do you get into that mental space when creating that allows for the subconscious to take over?

John Gnorski: Allowing room for the subconscious is really important to me because at the end of the day it’s very often the accidental/unintentional things that really resonate with me. To clarify, when I say subconscious in this context what I’m really talking about is allowing forces outside of my control to work in the picture/object. I try to maintain a decent level of competence when it comes to the basics of art-making, but I also try to use whatever “technique” I’ve developed to allow chance and accident to do their wonderful work. I know that nothing I could map out perfectly from start to finish will be nearly as interesting as something that transforms in ways I never could have anticipated through the process of the making.

This sensibility is very visibly present in the Rorschach-style pieces and a lot of my sketchbooks and works on paper, but it’s there in less obvious ways in all of my work. The lanterns, for instance, might appear as though each little bit of joinery was carefully plotted out, but in reality they are built based on pretty simple line drawings and constructed in an organic manner. I’ll have a basic shape I want to achieve, but the way everything is put together is done on the fly. Sometimes a connection might become redundant structurally as a piece grows, but I’ll keep it in there as a remnant of the process. All the little false steps and unintentional gestures become a part of the piece and give it a complexity I wouldn’t have achieved if I’d set out with a dialed-in plan and done things in the most elegant and minimal way possible.

The same is true of the ink on paper pieces which begin life as charcoal drawings and allow chance to seep in throughout the process. I rub the drawings onto plywood “plates” which transfers them in an imperfect but legible manner. I’m also using multiple plates and pieces of paper to allow for misalignments, and the plates themselves are of a type of plywood that tends to have an active grain that sometimes splinters or “runs”—interrupting the carved line in often surprising ways. I hand print the plates, which produces unexpected textures, and then go back into the image with more ink or sometimes collage or pastel. So in the end what began as a pretty clear and maybe even graceful line drawing becomes, through the welcoming-in of chance, something a bit more nuanced and awkward, full of special little moments on its physical surface that come out of that totally not conscious place of process.

Studio AHEAD: Tell us about EARTH BABIES, your collaboration with Kate Bernstein. We are particularly interested in how collaboration impacts the creative process—we have many ideas about this at Studio AHEAD and those ideas are constantly evolving. Do you find it easier to work alone or with a partner?

John Gnorski: EARTH BABIES is the conceptual tent that shelters all the collaborative work that Katie and I do together. It started as a music/installation performance at an amazing event called Spaceness that friends of ours organized for 5 years on the coast of Washington at a place called the Sou’wester.

Spaceness was a very free-form community art-making event that revolved around the concept of the unknown, and often featured work relating to outer space or unexplored worlds. It was held annually in early spring—the very darkest and dreariest time of the year in the Pacific Northwest—and it featured music, dance, video, radio, you name it. Folks would work for months on their contributions, and it was so beautiful: community coming together to make their own entertainment and help each other through dark days. For me, this is the best case scenario for art-making. I like to think of it as subsistence art—art for fun and joy and also for survival. It honestly makes me tear up thinking about it, and I often cried during the performances there. It just moves me so much to see what people can make with little to no budget out of the simplest materials like cardboard, scrap wood, clip lights, fabric, words: whole worlds that can really put you under a spell, transport you, communicate a message, and make time and space for our imaginations to nourish one another.

Anyway (and forgive me, this is going to get maybe a little esoteric) Katie and I, inspired by a trip to Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, came up with this idea of a whole culture of beings living deep under the surface of our Earth called “Earth Babies.” We first wrote and recorded songs based on this imaginary world, and over the years we made various installations: the “Healing Machine” which was a sound bath in a hand-built A-frame in the woods and the “Hopler Archive,” a fictional natural history museum.

At this point, EARTH BABIES is the name we use whenever we want to make something creative without the burden of our “actual” identities getting in the way. It’s our shared alter ego that allows for maximum creative expression.

As for collaboration generally, as much as I love spending time alone in my studio, my ideal art making ratio would be 25% solitary practice, and 75% collaboration. I love the energy of working with other artists, performers, thinkers, etc., and I think that collaboration leads to amazing things no one ever could have come up with on their own. I also think that community events like DIY music shows, theater, potlucks and ephemeral art exhibits in informal spaces are the most heartfelt and wonderful forms of art —purely collaborative and collectively authored. Again, it’s that idea of “subsistence art”. If none of us had to worry about selling our work I think there would naturally be a lot less emphasis on individual style and a lot less concern about authorship. Maybe collaboration would be the new norm and we could all contribute a verse to the big song we sing to sustain ourselves.

Studio AHEAD: What's your favorite music to listen to while making art? You are also a DJ and musician.

John Gnorski: Katie and I host a radio show on West Marin’s community radio station KWMR every other Sunday morning, which has really made us feel connected to the community out here.

I listen to a huge variety of music in my studio from atmospheric/ambient music like Brian Eno and Hiroshi Yoshimura to soul to Neil Young to Terry Riley to Alice Coltrane to Lucinda Williams. I’ll often just rely on my cassette library to take a break from the digital realm, which features a lot of mixtapes from Mississippi Records, my favorite record store/label. But if I had to choose only one thing to listen to while making art it would be Ornette Coleman. I’ve listened to a collection of his recordings called Beauty Is A Rare Thing many thousands of times over the years in every studio, basement, garage, and shed I’ve worked in. His music has every color and emotion and gesture in it, and it radiates compassion and energy and love. It’s also difficult at times and can go from soothing to jarring pretty quickly, much like life. When I listen to a song like “I Heard It Over The Radio” I hear everything from voices harmonizing singing a folk song to animals making raucous calls to wind in the trees and rattling subway cars.

Studio AHEAD: What can you do in music that you can’t do in the plastic arts? And vice versa?

John Gnorski: For me the boundaries are pretty porous. As I alluded to earlier with the titling of my work, there’s a lot of crossover and dialogue between disciplines in my practice. It’s easier for me to come up with analogies. A skittering, hesitant line in a drawing conveys something similar to a thin, airy flute or a tentative phrase on a piano. Take a lyric like this one by Leonard Cohen:

Nancy was alone

looking at the late, late show

through a semi-precious stone.

It conjures all kinds of atmospheres and emotional states like a Rothko or an Alice Neel portrait. Whenever I hear Alice Coltrane play the harp I think of someone painting with absolutely every color on their palette.

Music, however—live music—does have the wonderful quality of being ephemeral that most plastic arts don’t possess. It allows you to really inhabit the moment if you choose to. As a performer you’re also able to collaborate with an audience in a way that’s much harder to do with visual art. If you can engage an audience, or are part of an engaged audience, it can really make the experience special, with everyone kind of rooting for the performers and contributing their attention and energy to make the whole experience really lovely.

Then I suppose there are some stories that can be more eloquently told in pictures or gestures than in sound. Light can be captured really evocatively in a drawing or a painting and used to make form in the realm of sculpture. There are some feelings you can only get, some ideas that can only be conveyed, when you’re in the presence of a physical thing.

Studio AHEAD: I want to end on the very first photo posted on your Instagram. It’s a poster that says: “Now is the time to do your life’s work.” How do you or how do you try to live this mantra?

John Gnorski: I made this picture as a kind of personal affirmation to hang on my studio wall many years ago. A lot of people who came through commented on it and it seemed like most everyone appreciated the reminder.

My idea of my “life’s work” changes all the time, but the constant is a commitment to making things that I hope will tell a story or convey a feeling clearly and with heart. At times it can seem like art is some kind of luxury or commodity, but then I remember how it has truly illuminated and influenced and given hope and shape to my life and the lives of a lot of other people over the entire course of human existence. I think that being an artist is as noble a vocation as any, and more helpful to humanity than a lot of things I could be doing with my time.

I’m in the fortunate position of being able to primarily make a living by making art and other art-adjacent objects these days, but in the recent past when I would be laboring away at a carpentry gig, I would think of that image and that mantra and remember that I had some kind of calling beyond the job that paid the bills—a “life’s work” that couldn’t be defined by an hourly rate—and that the artist work deserved and demanded my commitment. I still believe that if I show up for the muse or universe or whatever you want to call it everyday, ready and willing to work, that I’ll be able to somehow keep doing this as my life’s work and hopefully make things that help other people see life or hear it or survive and take joy in it.

Studio AHEAD: We love that. We always start with asking our clients how they live. It's so important. Can you give us three creative people/places/cultural forces based in Northern California that we should take note of?

John Gnorski: Cole Pulice is a musician/composer living in the East Bay whose music often keeps me company in the studio. We also listen to a piece of theirs almost every day on the short drive from our house to the trail that we walk to check on the animal neighbors and greet the day.

Bolinas/Pt.Reyes/Inverness DIY art/music scene This is an acknowledgement of the type of creative community vitality that to me is the heart of sustaining art-making—artists, musicians, writers—we can also get specific and talk about it in terms of two spaces where most of this stuff takes place: the Gospel Flat Farm Stand and the hardware store in Bolinas. Both are DIY spaces of the highest caliber that provide the setting and the energy for art to happen.

Ido Yoshimoto. I know that everyone reading this probably already knows Ido’s work [if not, we interviewed him here —SA] but I feel compelled to shout him out because he so generously invited me into the community here when we landed a few years back. He’s also shared knowledge and food and time. The people who make their lives here and share their talents and have profound respect for the land are the soul of this place, and Ido is one of those people.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mendocino National Forest seeks public comment on McIsaac Ranch Land Exchange Project

MENDOCINO NATIONAL FOREST, Calif. — Mendocino National Forest officials are requesting public comment on the draft environmental assessment for the proposed McIsaac Ranch Land Exchange Project.

0 notes

Text

JINEN

JINEN is a traveling exhibition with new work from Dan John Anderson, Ido Yoshimoto, Kazunori Hamana, and Yu Kobayashi. The artists, two living and working in California, and two practicing in Japan, are drawn together here to explore the shared interests of their varying practices which are each inspired at a fundamental level by their own experiences of living with nature. In origin this project emerged organically between the four artists through shared inspirations that blossomed both in a moment and over time. The end product is a proposal in which the artists exhibit works in two very different yet iconic Californian landscapes: A-Z West in the Mojave Desert and Salmon Creek Farm in the coastal redwood forests. For the first iteration of this project the artists will install their works in and around the "A-Z Planar Pavilions" at A-Z West, an artwork and 80 acre compound by artist Andrea Zittel in the Mojave town of Joshua Tree. For the second iteration, the artists will install their works among the shaded depths of the Redwoods at Salmon Creek Farm, a former counterculture commune and now a queered commune-farm-homestead and land-based non profit by Fritz Haeg on the Mendocino coast.

Presented by Curator's Cube, JINEN will take place at A-Z West in Joshua Tree, CA from April 19-22nd, 2024 and then travel to Salmon Creek Farm in Albion, CA from May 3-5th, 2024.

Please reach out to [email protected] with inquiries and requests for private viewings which may reach outside of these posted exhibition dates.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 2: Greñas

I arrived in El Paso for the first time on a morning flight in February, 1981. The weather was brilliantly sunny and unseasonably warm compared to San Francisco, where it was raining and cold. Brian and his wife Melea met me at the small, provincial El Paso airport in a perfectly restored pastel pink 1963 Cadillac convertible with the top down exposing a pristine white leather interior. As I climbed in the back seat, Melea and Brian greeted me with that Texas accent that was at once subtle and disarming. “Ya’ll are from California,” Melea said excitedly, “We love California. We’re out every year to San Diego. Where ya’ll from?”

I told Melea that I lived on the southern coast in Mendocino county, part of the “Emerald Triangle” north of San Francisco where the best cannabis in the world was grown. I explained that I had concealed a small sample that illustrated the quality of the product grown there, eight ounces of a new genetic hybrid from Northern California, transported using new, odor resistant packaging techniques, in my luggage. I explained that Brian had asked me to save four ounces for our project, but that she was welcome to the rest.

“Thank you, Honey, but we’ll smoke that in a week.” “Oh my God,” Melea said, “we love California home grown here in Texas. How soon can you bring me some more?”

After we had driven a short distance from the airport, I passed a pre-rolled joint I had packed separately to her and Brian from the back seat. The samples I brought were long manicured branches with huge flowering tops that looked like small baseball bats. Glistening with trichome resin, and with a pungent skunk aroma, they looked and smelled impressive.

Melea was a striking figure, a statuesque woman with long, waist length blonde hair and light blue eyes. On any day, at any time, she would be wearing at least a quarter million dollars’ worth of traditional and contemporary New Mexican or Native American styled jewelry, necklaces and belts, with precious stones, diamonds, and sky blue turquoise. She had unique custom Rolex models not available to regular clientele, dripping with large diamonds, and, always, one of her Hermes Birkin or Kelly bags. She always mispronounced Hermes, but no one corrected her. “I’ve got to have my Her-meees,” she would say. She combined these affluent decorative accents simply with Wrangler jeans, silk blouses and exotically skinned cowboy boots. The accumulation of Melea’s wearable art created the impression of an African queen from one of the groups that emphasized long necks piled with gold rings as the standard of beauty and as a display of wealth. After taking a hit Melea announced earnestly, “Honey you and I are definitely new best friends.”

The Cadillac was equipped with a technologically advanced sound system and the Bobby Fuller Four ballad, “I Fought the Law and the Law Won,” played at top volume as we smoked and drove to Brian and Melea’s home. I would come to discover that Bobby Fuller was a son of El Paso. The song had just the right combination of country and rock and roll to frame my first trip to Texas. The Cadillac’s audiophile grade sound system was completely invisible. Apparently, Melea had hidden an array of extremely small speakers in every vent and possible hiding place while still preserving the original white leather interior. Part of the trunk was devoted to a couple of large hidden amplifiers that drove the speakers to create a dazzling ambience effect like a concert hall.

As I walked in the front door, I saw that Brian and Melea’s traditional adobe styled home was built around an expansive inner courtyard with a garden of Hibiscus, Bougainvillea, Orchids, Bird of Paradise and palms. Melea had designed the home’s interior to reflect her interest in the Santa Fe architectural style. The rooms had thick adobe walls with the spines of Saguaro cacti along the plastered white ceiling.

Melea excused herself and retired to let us discuss business privately. After we sat down in the living room, Brian explained that we would be going to Ciudad Juarez that afternoon to present our proposal to bring genetics and cultivation techniques that would improve the yields and quality of the fields of the major Mexican cartel and smuggling organizations on the border. We would be meeting with “El Greñas”, Gilberto Ontiveros Lucero. Later, Gilberto told us that the nickname "El Greñas", or “Mophead” was given to him by "an Indian who worked for me cultivating marijuana" in reference to his distinctive Rasta inspired hairstyle. During his impoverished childhood in Mexico, he sold popsicles and worked as a carpenter, but he managed to finish high school and went to the United States, where he lived for several years and studied business administration while selling cars. Brian described Greñas as a young up and coming cartel leader who presently controlled all of the smuggling traffic in the El Paso/Juarez corridor.

Conventional historical accounts of the early years of Juarez cartel organizations identified Amado Carrillo Fuentes, as the leader and founder of the Juarez Cartel, but he had actually acquired his leadership position from Pablo Acosta Villarreal, the “Fox of Ojinaga”, when he was killed during a raid by Mexican Federal Police in the small village of Santa Elena, Chihuahua on the Rio Grande. Villareal was widely credited with instructing all of those in leadership roles in the cartels with the arcane knowledge of how to properly conduct a drug smuggling enterprise. Villareal’s exploits were celebrated in the famous narcocorrido, a traditional ballad celebrating drug traffickers, by Los Tigres Del Norte, called “El Zorro de Ojinaga”.

Although Villareal began as a key founding member of Juarez smuggling, he fell out of favor with Miguel Félix Gallardo, who had formed the Guadalajara cartel, the first major attempt at organizing all of the Mexican regional traffickers into a syndicate. After Villareal, it was Amado Carrillo Fuentes “El Señor de los Cielos”, the “Lord of the Skies”, who acquired his nickname from the fleet of thirty Boeing 727 and Falcon jets he used to smuggle drugs, who took full control of the Juarez organization. By removing passenger seats and baggage compartments in the fuselage, Fuentes was able to outstrip his competitors who only used small private planes that carried five hundred or at most one thousand pounds. Fuentes used his modified planes to transport up to nine tons at a time. Brian explained, however, that it wasn’t only Fuentes but actually a number of other drug traffickers who were also instrumental founders of the Juarez cannabis cartel and plaza in the 80s.

According to Brian, the key, but more covert organizers of the Juarez Cartel were Rafael Aguilar Guallardo, Rafael Muñoz Talavera, and Gilberto Ontiveros, the latter who would later be considered the first cartel supervisor of the Ciudad Juarez plaza. This largely ceremonial position was accorded to the individual who would deal directly with the brokerages who purchased cannabis at the main transit points in Texas. It was occupied by an individual who was expendable if the US government leaned on Mexico. The individual occupying this position provided a sacrificial shield that allowed both Mexican government officials and highly connected families who actually managed the drug trade to remain behind the curtain.

As his wealth and influence increased, "El Greñas" began to collect mansions, ranches, and luxury cars and purchased hotels like the Rodeway Inn in Casa Grandes and had begun construction on the Palacio del César luxury hotel in Juarez. He was always surrounded by bodyguards while traveling in his bullet proof Rolls Royce limousine. Sometime later, during the festival celebration of Saint Buenaventura, when horse racing and cock fights were held, Greñas, who had a passion for horse racing, bet a million dollars on his horse to win a short distance quarter horse race. When the municipal authorities determined that drug traffickers were participating, they tried to stop it, but armed cartel guards allowed the race to proceed. Greñas entered his prize sorrel red horse but shrugged it off when he lost.

Greñas had the backing of the capitalizing principals of the developing Sinaloa cartel, like Rafael Muñoz Talavera and his brother who were just beginning to construct the Colombian cocaine trade. Greñas handled cannabis logistics for Rafael Caro Quintero, known as the originator of industrially produced sin semilla (seedless) cannabis of consistent quality in Michoacan. When Quintero’s cannabis operation at Rancho Bufalo (the Buffalo Ranch) in Chihuahua was finally destroyed by the Mexican army, it contained 540 hectares or approximately 1200 acres of high grade cannabis. A large proportion of it was cannabis from my Indica genetics sourced from Northern California. The ranch was later discovered by Enrique Camerena, the DEA agent who was subsequently killed by Quintero in retribution. The army netted approximately six thousand tons, worth billions, in the raid.

Greñas also worked with Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, “El Padrino”, the “Godfather,” and former official of the Mexican Federal Security Directorate (DFS), who organized the small trafficking organizations into the collective smuggling powerhouse that became the Guadalajara cartel. Gallardo was credited with creating a seamless drug highway from Colombia to Guadalajara to Juarez using a “plaza” system in which each municipal organization would hand off responsibility for a drug shipment to the next geographically in line. He forged a relationship with Juan Matta-Ballesteros, who introduced him to Santiago Ocampo, his connection to the Cali cocaine cartel in Colombia. As time went on, I was to form a close association to all of these progenitors, inviting them to dinner at my home in Tiburon and parties at the best restaurants in San Francisco and Beverly Hills.

Greñas was outspoken about the cannabis that was cultivated under the direction of Quintero in Michoacan, and competed to represent those sources as producing the highest quality to his Texas brokers. Referring to me, Brian had told Greñas that he had a university professor who was an expert in both the genetics and cultivation of cannabis, whose guidance and genetic products Greñas could use for his own or for Quintero’s fields in Chihuahua. Greñas wasted no time bragging about the new technology and expertise he was to acquire, saw an opportunity to use these new agricultural advances to distinguish his cannabis production, and to show Quintero and Gallardo that he could produce a better crop than they could.

After we finished talking, I got the samples from my luggage and met in the garage where I got into the back seat of Brian’s Mercedes. I put the two baseball bat sized branches, still in their plastic packaging to prevent the odor from permeating the entire car, into a paper sack. I had just arrived in El Paso for the first time and we were already going to Mexico. I had some apprehension, but Brian had assured me that everything was safe and we enjoyed the cartel’s protection.

El Paso and Juarez are separated by a bridge over the Rio Grande. In the middle of the bridge is a sign marking the border between the two countries. On the day we approached crossing to the Mexican side, there was a traffic jam of cars on both sides of the border. The line of cars entering Mexico was moving much more quickly, hardly stopping at the customs booth. I began to get nervous with the paper bag of cannabis baseball bats sitting on my lap. As we approached, Brian turned around to the back seat. “I hope ya’ll have that hidden. They might inspect us.” It was later that I learned Brian was always joking. We were the next car in line and my palms were sweating. Then, miraculously, we sailed through without the Mexican customs agent even taking a look at us. Brian turned around and smiled. “You’re as safe as you would be in a pot field in Mendocino,“ he said laughing.

We drove for about an hour into the suburbs of Juarez and finally entered a private street with only three houses on it. We pulled up to the house in the center of the block. It appeared unusual because it had a two story water tower on the lawn in front of it. I began to notice that everyone milling around seemed to have a specific job. The water tower was being guarded by large heavy set individuals in suits and ties wearing sunglasses and carrying AK-47s. We were approached by one of the guards who recognized Brian and used his radio to announce our arrival. We were escorted into the bottom story of the water tower where I saw more armed guards and a group of individuals sitting in a circle in chairs around the periphery. One of the guards protected the stairway while another silently indicated an empty chair for me. Everyone was waiting their turn to see Greñas and he was keeping them waiting at his pleasure. There was a stream of workers entering, steadily carrying U-Haul boxes up the stairs to Greñas’ office. Brian leaned over and whispered, “ Those boxes are filled with money.” We were at Greñas’ counting house.

I sat down next to a small older man with a dark complexion, dressed in the traditional style of Mayan campesinos, in a starched white shirt, white drawstring muslin pants, and wearing a flat brimmed hat with beaded artifacts dangling from the brim. It was an iconic style with which I was familiar from the ethnographic fieldwork I had done among the Mazatec and the Zapotec in central Mexico. It was a common belief that the ritual beads dangling on the brim of his hat would protect him from supernatural harm or avaricious competitors. I silently wondered why he thought he needed that protection.

I began a conversation in Spanish, but I could tell that his native language was Mayan, judging by his accent. He introduced himself as Don Pedro, master agronomist. I introduced myself and told him I was an anthropologist, a professor, and in the vernacular, a maestro or teacher. He nodded and told me that he was also a maestro. He said that he was in charge of all of Greñas’ cultivation projects, that he was the farmer of farmers, as he put it laughing, the Minister of Agriculture for the Ciudad Juarez cartel. He had been trained personally for his job by Rafael Caro Quintero and that he managed all of the seeds and genetics Greñas used as well.

I looked at Don Pedro and thought to myself, I guess now is the time. I told him that I too had an interest in agronomy and that I studied the genetics of “marijuana”. In fact, I told him, I have something with me that you, Don Pedro, would be interested to see. I had used a razor blade to open the sealed odor barrier bags in the car and had been holding them shut to prevent the overpowering terpenes from filling the room. Now I opened them and with one swift move, and pulled the two baseball bats of cannabis out of the paper bag. The skunk smell was overwhelming. Everyone turned around to look. Don Pedro’s eyes got big and he stood up excited.

“Please, pardon me,” he said as he stood up. “If you don’t mind, I’ll just be a moment.” He turned back. “May I?” he asked, indicating the large cannabis stalks I was holding. I offered them to him. He turned abruptly and walked to the stairs. The men with sunglasses and AK-47s respectfully parted and Don Pedro hurried past them. There was a brief commotion, a lot of walking overhead, and then Don Pedro returned, gesturing for us to come upstairs. The guards with sunglasses and AKs were brushed aside and we were taken upstairs to the corporate offices of El Greñas.

Greñas was up and animated behind his huge antique wooden desk. He was wearing a starched white shirt, tooled cactus belt and turquoise belt buckle, exotic boots and jeans in the elegant “Sinoloa” style adopted by narcotrafficantes(drug traffickers). He was pacing, shuffling through bags, talking in staccato machine gun bursts. “Just a minute, you’ll see,” he said, “where are my pinchi (derisively small, inadequate) buds?” One of the guards tried to help him. “Where the fuck are my fucking buds,” he yelled. He had a number of black garbage bags strewn around his desk and he was madly searching through them all for something. He opened one, reached in and stopped. He seemed momentarily satisfied. He pulled out a small cannabis bud. “See,” he said, “See. My buds are every bit as good as your pinchi buds. See, look.” He held up his small thumb size bud and compared it to the baseball bats. “See, every bit as good as your pinchi buds.” As he held the flowers up for comparison, he hesitated, but we remained silent. He seemed to momentarily come out of his drug induced fog and come to his senses. There was a fleeting moment when I believe he suddenly became aware of the sexual connotation that his flower was small and the machismo inuendo that it was inadequate compared to the one I brought.

In that moment, his mania ebbed enough for him to get some clarity. “Ok, let’s talk,” he said sitting down in his office chair and swiveling around to face us. After he sat down, he took a few more verbal swipes at the pinchi buds, “Fucking pinchi buds. Big fucking deal, my buds are just as good.”

As Greñas talked he began an elaborate ritual. He took a single Marlboro filter cigarette out of a new pack, and rolled it so the contents fell out to produce a small pile of tobacco. He took a baggie out of his shirt pocket that appeared to contain cocaine base, its smokable form. He continued talking, making disparaging comments, while he combined the tobacco and the base powder. Then he carefully loaded the mixture back into the flaccid filter cigarette, tamped it in using a toothpick, and then sat back in his chair with his feet up and lit his newly constructed cigarette. Greñas would spend the rest of the meeting lighting cigarette after cigarette. How does he stay even moderately coherent I wondered?

Surprisingly calmer after his smoke, Greñas seemed to relent at this point. “Ok, my gringo friends, I want you to supervise my cultivation. I will offer you five percent of the entire load which you must split with your Texas partners. I will deliver the marijuana to your buyers in New York and California. I will handle all the transportation, all the cost of crossing the border. Just bring me those fucking pinchi semillas.”

Greñas stopped talking and looked at me intently for several seconds. “If you fuck me on this, I will cut your nuts off and feed them to you. I will control all of the seeds and cultivation knowledge that you bring. We will begin by using your knowledge to improve my fields in Chihuahua as proof. Only then will we make this available to Rafael (Quintero). Brian has already explained to me how your plants are completely finished in two months. This will give us a tremendous advantage.”

“I want to show you where you will be growing,” Greñas said and he went to his file cabinet to pull out some Polaroid pictures. “Here,” he said and laid them out on the table. In the photographs, one could see vast fields of bright green cannabis, growing in a white, sandy soil, extending far beyond the limits of the foreground image. The most unusual aspect of the photographs was the appearance of Mexican army vehicles and soldiers in full dress uniforms in every picture. There were Mexican army soldiers guarding Greñas’ fields of cannabis, Mexican army half-tracks driving up dirt roads circumnavigating the fields, and Mexican army helicopters parked next to the growing weed. He noticed my surprise. “Yes,” he said, “we have the army under our control. We have the full protection of the Mexican government, the PRI. They will take down our competitors fields, but mine are always protected.”

Greñas discussed the current transactions he had underway with Brian, but there was certainly an increased sense of respect. Greñas knew that he was the one who had the fucking pinchi marijuana.

On the way out I chatted briefly with Don Pedro. “I assume we will be working together, my friend,” he said and bowed in my direction. “I look forward to that day with great pleasure.” I said and thanked him for his help. We were escorted from the compound by the guards who saw us all the way to the car.

I left the meeting feeling extremely satisfied. I would have all the money I would ever need and would have the opportunity to pick phenotypes from one of the largest cultivation projects in Mexico. Greñas would deliver to my buyers. He would handle crossing the border. I looked at Brian. We both knew we had it made. What could possibly go wrong?

0 notes

Text

Granite bags $23M contract from Caltrans to upgrade Highway 101 in Mendocino (NYSE:GVA)

Granite (NYSE:GVA) has secured a contract from the California Department of Transportation to upgrade Highway 101 in Mendocino. The contract has a value of $23 million. Project funding will come from the Federal Highway Administration and is expected to be included in the company’s second-quarter CAP. The company will upgrade four miles of median barrier and resurface a ten-mile section…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

It is the 10th year anniversary of A Year of Deep Creek, long ago become A Year of Erewhon. Not without its troubles, mostly caused by the platform itself, by Tumblr. But also not without considerable joy and growth through the whole project. Ten years ago today, this was my first post—I wonder who I thought would ever see it? ... When you start a blog and have 0 followers. But things progressed quickly, and the collective love for this place and its spirit spread.

I started things that day ten years ago with a panorama of paradise. It had been taken and posted online by an artist named Fritz Haeg. I think I associated him with an artist collective named Fallen Fruit, that I had encountered over the years at the springs. I may have confused his older project called "Edible Estates." He was trained in architecture and living back then in a geodesic dome in LA. I didn't realize it might be a prophetic post for the blog, but he has gone on to transfer his art practice to the rehabilitation of an old hippie commune in Northern California, in Mendocino Country, that is called Salmon Creek Farm. I recommend you check it out. This is the post that started things for this page, here. Coming full circle.

https://salmoncreekfarm-commune.org

Paradise

http://www.fritzhaeg.com/wikidiary/tag/deep-creek-hot-springs/

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally, No GenAI Hocus Pocus (A new DUET?)

What is the difference between DUET 2007 and DUET 2024?

While most solution providers are using smoke and mirror claims of sentient capability to cash in on the latest dot-com-type buzz that is today’s GenAI craze, the “Real” GenAI providers know that their success today is built on processes and technology that existed in the late 1990s. That’s right; they recognized the power of true connectivity, which leverages technology to empower human…

0 notes

Photo

The Quilted Wall of Change Workshop: Next Class October 5 & 6 at 10:00 AM

As part of the upcoming Phoenix Project, Mendocino College is hosting a free workshop in which participants will create an up-cycled quilted wall led by local quilt legend Laura Fogg. This free hands on workshop is a special opportunity that will allow participants to contribute smaller pieces to a large outdoor artwork installation that will be hung at Mendocino College during the Phoenix Project events. The Phoenix Project is a multi-disciplined series of events that have been designed to recognize the devastation of the 2017 fires and how the community is moving forward in the face of a changing climate and environment. Workshops will be held from 10 am until 4 pm, September 7 and 8 and October 5 and 6 in the CVPA building at the Mendocino College Ukiah Campus. The Mendocino College Ukiah campus is located at 1000 Hensley Creek Rd. For more information and to register for the workshop please email [email protected] or call 707-485-4379.

#art#ukiah#phoenix#quilted#Laura Fogg#mendophoenixproject.com#Mendocino College#Mendo Phoenix Project#Phoenix Project

1 note

·

View note

Text

2022 was an eventful and challenging year in many ways:

-B and I struggled to find our groove as a married couple and committed to breaking our negative cycles and patterns together.

-We celebrated my dad’s 70th birthday (69 but 70 according to the Chinese calendar)

-I went roller skating with my nieces

-We hosted and celebrated LNY with yummy food and roasted marshmallows in the backyard.

-We went to an immersive art exhibit.

-I hung with my sister friends: painted with Lily and Catherine, visited Leslie, Nicole and Maya.

-Brent took me to see Justin Bieber and Jaden Smith for my belated birthday.

-celebrated Lily’s birthday with an escape room and brunch

-took my parents to the Ruth Bancroft Botanical Garden

-hosted my parents for lots of visits and meals

-picnicked by Lake Merritt with coworker friends

-had a board game day with the Lambs

-hosted Megan’s baby shower in SD with Diana

-volunteered to pack meals for Ukraine

-traveled to Cancun to celebrate Michael and Edison’s wedding and love with the UCSD fam

-road-tripped to visit Jordan and Nicole (and Maya and the pets!) in Sac

-celebrated Andrew and Bryce’s wedding in LA

-caught up with LA friends/fam: Andrew and Kyle and Garrett

-had a bbq girls date with my sister and nieces

-went to the AAPI Community Festival with Catherine and met the directors of Turning Red

-hosted the first in-person orientation and social events since the pandemic

-supported Aunt Carole’s garden club plant sale

-saw Mount Westmore (and probably caught covid there!)

-saw Oh Wonder with Lily

-met Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul!

-traveled to Bergen, Norway with Catherine and saw the fjords! (Also learned what a fjord is lol)

-traveled to Stockholm, Sweden to launch a Global Internships program and finally meet Sabrina and faculty I had been working with for years for the first time!

-reconnected with Gerald in Stockholm of all places!

-Brent got in a car accident but got a new suv (bigger for more cargo!)

-We saw and met Earth, Wind, and Fire and Santana.. from the 3rd row!!

-celebrated Jiten and Preeti’s wedding with UCSD residents and friends

-celebrated Fourth of July with Andrew, Kyle, Adrienne, Chris, and Brent - lots of wine and kbbq of course

-traveled to the Middle East for the first time, and explored Jordan and Israel (Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa)

-explored Wadi Rum and Petra

-launched a new program in Haifa, Israel - a project that I started years ago

-celebrated Bobby and Perry’s colorful Toshiba themed wedding in Monterey

-celebrated our one year wedding anniversary!

-celebrated Brent’s birthday in SF with the stranger things experience and a seafood dinner

-danced the night away at the Backstreet Boys concert

-relived my youth at a throwback concert with Nelly, Ja Rule, Ashanti, and Lloyd

-went to a Giants game for Victor’s 70th birthday

-volunteered to host Comedy Night for Cal freshman - for the first time since the pandemic

-caught up with Global Glimpse Brent over Indian food

-hosted Madison and Leah for a sleepover: and played lots of animal crossing and games

-saw Jazz is Dead in SF

-saw Kendrick Lamar!

-spent Labor Day in Mendocino: eating bomb seafood, picnicking at the winery, and walking to see the seals

-celebrated Catherine’s birthday at Rupaul’s Werk the World Tour

-celebrated Maya’s 6th birthday

-drag brunch with coworkers and friends

-family trip to Groveland and Yosemite to hike, eat, and drink

-taught a freshman seminar class - in-person!

-hiked Muir Woods with Alyssa, Clark, and Brent and had bomb Puerto Rican food after

-saw Lupe Fiasco in SF

-presented at the Diversity Abroad Conference in SF

-presented at FORUM CIGL in Milan, Italy

-traveled to Lake Como, Bellagio, and Verona in Italy and Lugano, Switzerland with Lily.

-celebrated Scott and Kristen’s wedding

-celebrated Kenzie’s 3rd birthday

-celebrated my 34th birthday with Jose in Arnold

-finally took my parents to HOPR!

-hosted the fam for thanksgiving hot pot

-celebrated thanksgiving dinner with the Costas

-saw Clue at the Lescher Center for Performance Arts with Brent’s parents

-saw Bow Wow, Lloyd, and other throw back artists

-went to Disneyland and California Adventure, and got to stay at the Grand Californian Hotel!

-took a day trip to Petaluma to reset and reinvest in our relationship

-ate and drank our way through a cheese advent calendar with Adrienne and Josephine

-watched my nieces perform in their annual Hoike

-celebrated a quiet Christmas with our little family

-visited my parents in LA for a couple days, managed cancelled flights and rented a car to get home

-celebrated a belated Christmas with Brent’s parents, Sharon, and aunt Carole

-and ended the year with a flood garage!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In recent years, purple sea urchins have proliferated along California’s Mendocino Coast, as a result of a combination of factors, including climate change. Photograph By Mark Conlin, Alamy Stock Photo

Want To Help California’s Kelp Forests? Eat Sea Urchins.

Purple sea urchins have eaten 95 percent of the underwater forests along California’s Mendocino Coast. Here's how you can help.

— By Kristen Pope | July 20, 2022

Looking out over the Pacific Ocean, diners at the Harbor House Inn’s bluff-top restaurant in Elk, California, are accustomed to finding locally harvested seafood on their plates. But one ingredient plucked from the waters below makes more than a delicious meal. Eating purple sea urchins when they’re available is part of a local conservation effort.

Purple sea urchins are contributing to the destruction of kelp forests, a key component of the region’s coastal ecosystem that sustains a wide variety of sea life. In recent years, these life-giving underwater forests have been disappearing at an alarming rate—about 95 percent of the area’s bull kelp vanished between 2014 and 2019.

Mendocino County, California, includes 90 miles of pristine rugged coastline, drawing nearly two million tourists annually. Photograph By Gary Crabbe, Enlightened Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Sea stars keep urchin populations in check, but sea star wasting syndrome has decimated their numbers. This, plus marine heatwaves, climate change, and El Niño have contributed to a “perfect storm” of conditions, rapidly degrading Mendocino County’s once thriving coastal ecosystem. In recent years, scientists have found 60 times more kelp-munching purple sea urchins than normal.

Giant kelp normally thrive in the waters along California’s coast. In recent years, rising populations of purple sea urchins have eaten through 95 percent of the underwater forests. Photograph By David Fleetham, VWPICS/Redux

Left: Purple sea urchins, growing unchecked, creep toward bull kelp in Mendocino Headlands State Park, in California. Right: Purple sea urchins are prevalent all along California’s coast. Here, a few cling to a stalk of palm kelp in Monterey, a popular tourist town south of San Francisco. Photographs By Brent Durand, Getty Images

“In a lot of places it looks like someone clear-cut the forest and then rolled out a purple carpet all over the sea floor,” says Morgan Murphy-Cannella, kelp restoration coordinator for Reef Check Worldwide, a nonprofit focused on volunteer science to conserve reefs and kelp forests.

Despite a slight increase in kelp since 2020, in correlation with upwelling (when wind brings nutrient-rich cold water), scientists say the problem is far from over. “The ocean … is nowhere close to being back to a completely healthy and restored ecosystem,” says Tristin McHugh, kelp project director for the Nature Conservancy.

How can travelers help? While scientists keep an eye on the data, visitors can learn about the coastal environment, volunteer with local beach cleanup efforts—and dine on the urchins wherever they’re available.

Eating Sea Urchins For Conservation

At the Harbor House Inn, executive chef Matthew Kammerer turns the echinoderm into the Michelin-starred fare his restaurant is known for. After carefully cracking open their outer shells, he removes and cleans the edible inner lobes before adding them to a savory Japanese-style egg custard called chawanmushi and a porridge made of local grains. He also serves them in a dashi sauce drizzled on strips of celeriac that mimic pasta. Pieces of urchin are even whipped into butter and candied, with each preparation showcasing the myriad of ways to chow down for a good cause.

Top: A diver brings up net bags full of purple sea urchins. Restaurants rely on local divers to handpick the urchins because there is no viable way to harvest them commercially. Bottom: After cracking the outer shell, a worker scoops out the edible gonads from a sea urchin. Photographs By Meg Roussos, Bloomberg/Getty Images

Kammerer isn’t the only top chef cooking for conservation. Chefs at Little River Inn in Little River and Izakaya Gama in Point Arena have joined the culinary cause, too. These cooks try to use purple sea urchins whenever they can, but despite their abundance in the ocean, they’re difficult to source. Currently, there is no established method of harvesting them for restaurants, so the chefs rely on local divers or harvest them on their own. When they can’t get purple urchins, many use larger, commercially available red urchins.

No matter which kind of urchin appears on the plate, locals hope that seeing them on menus more often will help break down the barrier to eating the spiny invertebrate, which can seem intimidating.

Kammerer began serving them four years ago, and so far, diners have been positive. “We ask our guests to trust us, and they end up usually really, really enjoying it and getting their minds changed,” he says.

In addition to serving purple urchin, chefs and locals hope a new annual festival will help spread the word. Held in June, the first Mendocino Coast Purple Urchin Festival hosted cooking demonstrations, educational events, and urchin-focused restaurant specials, plus a preview of the upcoming Sequoias of the Sea documentary telling the story of California’s kelp forests.

Sea urchin can be prepared in a variety of ways. At Sierra Mar at Post Ranch Inn, in Big Sur, California, a lobe of urchin tops ahi tuna raviolo with sea urchin mousse, red shiso, ponzu, and wasabi oil. Photograph By Lucyd Photo, Getty Images

“For me, the urchin festival is really about teaching people what’s going on underneath the waves,” says Cally Dym, owner of Little River Inn, one of the festival’s hosts. “Eating the purple urchin is our way of helping the whole ecosystem down there.”

Sheila Semans, executive director of the nonprofit Noyo Center for Marine Science, which received a share of proceeds from the event, says her goal is to get everyone in town to give urchin a try for the environment. “We’re trying to elevate the conversation beyond not doing as much harm to actually improving the environment by eating this seafood,” she says.

More Ways To Help Save Kelp Forests

Beyond patronizing local restaurants, Mendocino County visitors can explore the Noyo Center for Marine Science in Fort Bragg. Inside the center’s geodesic dome, video of a kelp forest and an urchin barren helps place visitors at the heart of the problem, while a walk-through art installation of a kelp forest provides in-depth detail. Soon, an interactive component will teach kids how to build a coastal ecosystem model using magnets shaped like urchins, sea stars, and abalone.

A diver inspects a stalk of giant brown kelp reduced to a holdfast by purple sea urchins that continue to attack the bare stalk. Photograph By Waterframe, Alamy Stock Photo

The center’s volunteer science program lets trained community members wade into the problem through beach surveys that track what washes up on shore, such as segments of bull kelp and abalone, in addition to urchins. Another program gathers volunteers in search of juvenile sunflower sea stars. One outing logged the first sea star spotted in Mendocino in five years, Semans reports. Visitors can join occasional beach cleanups, too.

Since 1984, scientists have been tracking changes in the kelp canopy all along California’s coast. Now the Nature Conservancy, UCLA, UC Santa Barbara, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution have partnered to make that data available to scientists and volunteers through a newly launched site, called Kelpwatch.

Coordinated groups of divers have contributed to restoration efforts, too. Nearly 50,000 pounds of purple urchins have been collected through a partnership involving California government entities, communities, and nonprofit organizations, including Reef Check Worldwide, Watermen’s Alliance, the Nature Conservancy, and the Noyo Center for Marine Science.

Together with these conservation efforts, Kammerer hopes that every bite of purple urchin he and others serve is a step toward restoring the kelp ecoystem.

“The more information people know, the more sea urchin they’ll eat, and hopefully,” he says, “we can help make a difference.”

— Kristen Pope is a freelance writer covering science, conservation, wildlife, and climate change.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good news about news co-ops

Today, the Global Investigative Journalism Network reprints The Nonprofit Quarterly's exciting story "A New Business Model Emerges: Meet the Digital News Co-op," by Tom Stites.

https://gijn.org/2021/03/25/a-new-business-model-emerges-meet-the-digital-news-co-op/

https://nonprofitquarterly.org/a-new-business-model-emerges-meet-the-digital-news-co-op/

Stites documents the rise-and-rise of national news co-ops in Germany, Italy, Switzerland and Mexico, and the rapidly proliferating local co-ops in Canada, Uruguay and the UK.

A news co-op is a news organization owned by its readers, whose membership fees pay for open access journalism - no paywall - usually organized as nonprofits (an IRS rule-change lets for-profit newspaper convert to nonprofits).

The reader-owners of the co-op get to read the news, vote on the co-op's policies, elect its board, ensure their communities are being reported on, and get members' access to private forums where the co-op's business is discussed.

Co-ops court advertisers for inclusion in a supporter's business directory, and ads in a news co-op's publications demonstrate a business's connection to its community to both the co-op's members and the community-wide readership.

Stites draws a comparison to the credit union movement, which is larger - in aggregate - than Wells Fargo, but whose control is decentralized among 5,133 community-oriented financial institutions (I love my credit union).

US news co-ops are on the rise, including The Devil Strip and The Mendocino Voice. Stites describes how his nonprofit Banyan Project serves as an incubator for news co-ops:

https://banyanproject.coop/

The much-lamented local newspaper industry was an historic accident: newspaper families connected sports-score-hungry readers with local appliance store ads, and spent some of the profits that generated to cover city hall and the state-house out of a sense of patrician duty.

Long before Craigslist, long before the Googbook ad duopoly, these weird, contingent structures were crumbling, as newspaper families sold out to vulture capitalist raiders who gutted the papers and looted their rainy-day funds.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/03/18/news-worthy/#big-news

The news part of newspapers was never a standalone business, irrespective of whether readers paid for the news or got it free - for general news, there's always been a cross-subsidy that was a mix of market forces (appliance ads) and civic duty (patrician news families).

The news co-op model acknowledges that news is, in part, a public good - news that isn't widely available is not "news," it's a "secret." The premise that paywalls and ads will give us back the local news that covers readers' liveaday issues has not been borne out.

Paywall success stories are a mix of specialized news, often catering to the ultrawealthy (WSJ), superstar news orgs focused on specific national and international news (NYT) or news with billionaire backstops (WP).

The civic function of news is not met by any of these models. But reader-supported, open access news, like Canadaland and The Halifax Examiner are filling in the gaps. The co-op model is a most welcome adjunct to these success stories.

Image: Co-Op (modified): https://www.flickr.com/photos/theco-operative/12541909913/

Paul Williamson (modified): https://www.flickr.com/photos/mustbeart/6322535993/

CC BY: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mendocino National Forest initiates trail segment reroute project

MENDOCINO NATIONAL FOREST, Calif. — The Mendocino National Forest’s Upper Lake Ranger District has initiated a project to reroute and restore a segment of off-road highway Trail 35.

0 notes

Text

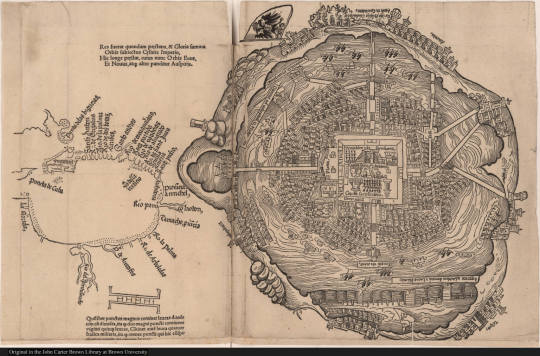

From Oaxaca to Mendocino to Abruzzo.... a new embroidery underway.

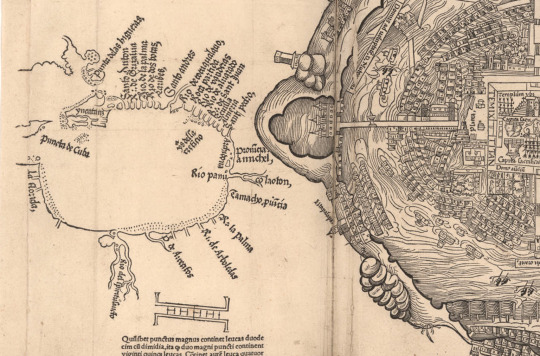

Through researching Durer and his Rhinoceros, we learned that he printed a woodcut map of Tenochtitlan (pre-hispanic Mexico City) that was published in a 1524 edition of Hernan Cortes’ letters to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, celebrating his conquest of the Aztec Empire.

Nuremberg, where Durer resided, was a center for printing, cartography, weaponry, and finance during this time of Empire building. Nuremberg investors financed a great deal of Spanish colonial exploration of the New World. Spanish firsthand accounts of the New World were published in Nuremberg and disseminated throughout Europe.

The map is a European interpretation, based on Cortes’ accounts, of an American indigenous cosmology. The image itself is oriented with south at the top, the left hand side of the map represents, at a very different scale than that of the city, the Gulf of Mexico and Southeastern United States, including Florida. On the right is the city of Tenochtitlan, under the Hapsburg flag, surrounded by Lake Texcoco, with the raised causeways that linked the island city to the mainland. At the center of the city is the temple precinct, and at its center are the twin temples that were dedicated to the deities Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli, gods of water and war, respectively.

Like the rhinoceros, Durer never saw Tenochtitlan. And, like the rhinoceros, the Aztec city and the lake that surrounded it, were displaced by colonialism. This map of Tenochtitlan is now the foundation for another monumental, collective embroidery and eventual work in paper.

In 2018, we were invited to the TEXTIM III conference hosted by the Museo Textil de Oaxaca, in Oaxaca, Mexico, to launch this new embroidery.

In 2019, We held our first US sewing circles on the map in conjunction with our exhibition at the Mendocino Art Center.

After the exhibition came down, we were taking a break to assess the whirlwind of the past few years, and our future plans for Rhinoceros Paper Pours and Map Sewing Circles, when all came to a stand still with Covid.

Like for many of you, we’re sure, 2020 was a year of quarantine and social distancing. During that time, we began to embrace ideas of slowing down, intentionality, and the importance of stillness.

This past summer, though, as things seemed to be opening up, we were invited by LAB-8 to bring the Map project to Abruzzo, Italy, as part of a new artist residency program: Riabitare con l’Arte.

We stayed in the Comune di Barisciano, in Abruzzo, and held sewing circles there, as well as in Fontecchio, Panfilo di Ocre, Acciano, and PIcenze.

Like the Rhinoceros, the map will become a document and a story, evidence of the many hands that contributed stitches, and now also a material record of the places to which we travel.

While we are still grappling with exactly where to go and what to do to move this project forward in its best form, what is very clear to us is the importance of using these historical images that speak to intersecting histories as jumping off points for conversations from many different contexts and perspectives.

Over the course of gathering, sewing, research and writing, we’ve honed in on some key ideas that we want to continue to investigate moving forward:

1. From a contemplative perspective: That perhaps change can come from stillness as well as from action. That stillness is substantially different from stagnancy, and that creating a still, meditative, communal listening space is a powerful age-old tool that we want to continue to engage. That creating this space around a communal material project, can aid in reconnecting us to our bodies and our material realities - our environments and the land beyond.

2. From a political/social action perspective: That in order to best engage social and environmental issues of today, we must dig deep into our personal and collective histories – going back to the beginnings of globalization - to tease out our common origins, interstices and divergences, and altogether how we arrived here at the present moment. That our primary goal might be to find commonalities, community, connection and healings in this time of insistent polarization.

#map#tenochtitlan#lagrantenochtitlan#albrecht durer#nuremberg map#embroidery#sewingcircle#rhinocerosproject#abruzzo#oaxaca#museotextil#italy#barisciano#fontecchio#ocre#mendocinoartcenter#acciano

5 notes

·

View notes