#Max Boisot

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tacit knowledge and high value work

Tacit knowledge is at the heart of high value work. Why? Because it’s complex. New post.

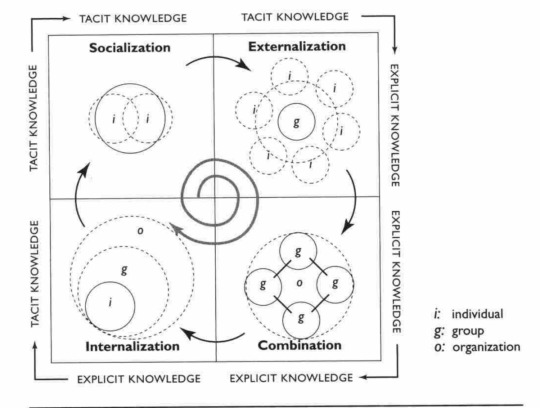

There was a lively discussion about the role of tacit knowledge over a couple of days at John Naughton’s daily blog recently. I’ll come back to the reason why the subject came up in a moment or so. I came quite late in life to questions of knowledge management, and my first exposure was to the work of the Japanese professors Nonaka and Takeuchi, and their ‘SECI’ model, which argues explicitly…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In future, the challenge will be to absorb uncertainty rather than reduce it

Uncertain times. Max Boisot (1998), Knowledge Assets.

0 notes

Text

Five things I’ve learnt about horizon scanning

Five things I’ve learnt about horizon scanning

I’ve been doing some project work and some training recently on horizon scanning, and this reminded me that I’ve been meaning to write up a talk I gave to a British government department called “Five things I’ve learned about scanning.” One of the underlying principles of futures work is that change comes from the outside. First, it happens in the contextual environment, then it starts to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Tweeted

In the chaotic regime, go with the headless chicken strategy. 🤣 Max Boisot and Bill McKelvey: Connectivity, Extremes, and Adaptation: A Power-Law Perspective of Organizational Effectivenesshttps://t.co/jss6HPvkzi pic.twitter.com/Ln1whOYyDI

— Mikael Seppälä (@mikaelseppala) February 19, 2020

0 notes

Text

story practice note, third and final part

In which we explore the 'felts' of stakeholder points of view, Who am I stories, metaphorical equipment, small stories that make a big difference, story listening, finding practice partner, and a few useful references to go exploring in. We end with collectors template.

stakeholders

The word stakeholder is dangerously abstract, and there’s a tendency to see stakeholders as an amorphous blob, or as an abstract, or even menacing concept. But unless you know, quite precisely, who you are talking to, how do you know the best ways of getting them to hear what you’d like them to hear?

As well as having listened well, you need to hold your audience in mind, and have them know that you can see and hear them.

In one piece of work we did recently, we invited people to get right under the skin of a frontline member of staff – imagine their name, age, country of origin, where they lived, what they looked liked, weighed, what they wore, what football team they supported, their family circumstances, how they felt about where they worked and their job today, how it had changed, what kept them awake at night, what their dreams were.

We invited people, in pairs, to step into, and inhabit, the bodies and shoes of their ‘factional’ characters (we called them factional because people pieced together their characters from actual personalities at work). What started as a bit of joke, even a bit of a caricature, surprised and moved people, sometimes almost shockingly so, as they came to understand, and feel for themselves, the circumstances people were facing and the threat that certain changes posed to their stability and wellbeing.

This is pretty much like most user profiling work, especially that done in agile technology design and development, or like the characters the BBC uses to check its radio station brand tunings, but it seems to surprise people and is worth remembering. The ‘what would Wolf say’ technique I blogged about recently is another way to use narrative techniques to bring stakeholders into the room. The different here is that we are taking it right into what David Bohm calls ‘felts’: the imaginary felt experience. The ‘felts’ are very powerful indeed. Another imagined ‘felt’ that can help change angles and perspectives comes from techniques like those used to work with museum objects: imagine your point of view as the chair on which this spy was assassinated.

A really felt sense of what it feels like to stand in the shoes of your listener will allow the story to shape itself so that the nature of the telling fits the circumstances.

Annette Simmons, in her book ‘Who Tells the Best Story Wins’ calls this the ‘I know what you are thinking’ story, which sounds quite confrontational but really means that you have a vivid internal sense of your audience, and hold that sense very present in your mind’s eye as you tell the story.

A white back I attended a graduation ceremony dressed in the kind of mediaeval pomp and circumstance which the newest, as much as the oldest, universities prize so greatly. Most of the speeches washed right over me and I spent a couple of hours listening to the names, sizing up the shoes and walks of the graduates as they walked the red carpet to and away from the handshake, and figuring out what degree most appealed to me (Arabic and English, closely followed by War and Conflict Studies). Then I sat up and listened, as the final speech started like this:

‘I’ve been sitting here watching the looks on your faces, and they tell a range of stories – joy, wonder, pride and, in at least one case, astonishment’

He saw them. You knew he’d seen them (whether he’d planned the speech or not) and you could tell by the shift in the sense and temperature of the hall that they relaxed a little, secure in the knowledge that he’d seen them. He had their listening ears. Recently I heard a bravura performance of the same kind from Greg Dyke at my daughter’s graduation. He managed, somehow, to acknowledge everyone in the room, as if personally.

The advantage of having shifted the balance of your time and effort towards listening is that you’ll already have done a lot of the work to find the shape and size of feelings of the people you are encountering. It will also help you find ways to step into their shoes without needing to accept their point of view.

a note on ‘story in a word’ (with thanks to Madelyn Blair

One good way into showing people you’ve seen them can be to acknowledge the mountain of rusting jargon lying between you. It stops you really approaching each other and getting close. Outcomes and outputs and deliverables and milestones and silos and blue sky and out-of-the-box thinking and plates needing to be stepped up to and high horses that need to be stepped down off.

Values like integrity, accountability, transparency, community spirit, innovation, perhaps spiced with courage (Standard Chartered) and heart (BT) or neighbourliness (UN charter). All of this clutters the conversation space and at the same time provides people with tactical defenses, places to hide or something handy to lob into the conversation as a diversionary tactic.

Story in a word can help (and also pre-empts a little the next section on Who Am I stories). It’s a way of reclaiming words and infusing them with the collective sense of the stories of people as the examples in the margin illustrate.

Here are some ways of using that technique, whether it’s in, say, an anecdote circle, starting with a blandk sheet of paper or a trigger story, or as a research question, even on postcards:

‘I know we throw the word transparency about and I’m not always sure we mean the same things or even think we know what it means. Tell me a little bit about a time when you’ve seen transparency at work in this partnership or another partnership and it’s felt like a good thing to you – so I can get a bit of a handle on how you’re thinking about the word in this context too.’

Or

‘Yes, it’s a bit hackneyed to talk about innovation in this context, I have to agree. But maybe if I tell you about something that’s happening in another project that feels innovative to us, that might help a bit?’

Or

‘It’s the word ‘authority’ that clouds the issue about what we do. Let me tell you a small story about that word in action so that you can get more of a feel for what I have in mind and see what stories it calls to mind.’

If you want to find out more about it, you’ll find a version of it in the SDC story guide in the publications here.

…and a note on metaphorical equipment

Good strong metaphors can do a lot of the heavy lifting for you too. They can find you a space between you and your audience in which to start a fresh conversation. So having energetically de-cluttered, you’ll have room to start using a new vocabulary, more precisely chosen to build a shared meaning between you and others. It’s worth remembering, too, that metaphors can do a lot more work than dressing things up. On occasion they change the course of innovation.

A small recent example of analogy and metaphor leading directly to invention is something I picked up out of the free evening newspaper, the Metro: the nozzles used inside Hewlett-Packard printer cartridges.

The idea of these is being redeveloped to help drug delivery and pain management.

One of my favourite examples comes from Jonathan Miller in his wonderful book of essays about organs of the body.

The heart was only seen as a pump when the combustion engine had been invented and was being used in sixteenth century mining, fire fighting and civil engineering.

Scientific progress in both cases, and many others, comes as a direct consequence of what Jonathan Miller calls in ‘The Body in Question ‘metaphorical equipment’. It took about 1500 years from first investigations into the heart until the analogies moved from lamps and smelter’s furnaces, through technological invention in an entirely different place, that a plausible analogy for the operation of the heart gave scientists a new take on things.

Max Boisot has written some good books on knowledge and information management. He comes from a background in architectural practice that he applies to the space he calls the information space. He talks about the continuum between conversation and commodity (i.e. between informal encounters and formalized exchange). But, says Max, the real moment of invention and insight is when you take something from one setting and put it into a new setting as a trigger to new thought. He calls this abstraction, and I don’t need to bother with it much more here, as this isn’t a knowledge management paper, but it may be useful background.

This isn’t to say that every metaphor or analogy will lead to transformation and invention, but it is to say that a well-chosen metaphor or analogy (or story) has a great deal more power than you may appreciate. Equally, a poorly chosen, or clichéd metaphor can close minds and end fruitful conversations. The balance is delicate.

who am I stories - Stripping off your organisational mask.

Annette Simmons also talks about the ‘Who Am I Story’, which is just as important. Look at any inspirational leader – Obama, Clinton, Mandela, or many people close to home who inspire you daily in quieter ways – and look at the pattern of their storytelling. You may get a polished version of the person, but with great leaders you’ll get a sense of them standing there, willing to be themselves, to see you and to accept the consequences.

A little while ago I had to step in at short notice for a colleague to run a workshop at a European investment bank, re-assessing their internal communication strategy in the light of the financial crisis. I was a stranger with no particular background in internal communications. Somehow I had to find a way to get them to give me permission to run the day. So I said

‘I was thinking on the plane over how much of a sense of déjà vu I had coming here. 20 years ago, I was sitting in front of the US and UK regulators trying to persuade them that index futures and portfolio insurance hadn’t caused the crash; 10 years ago I was part of an investment bank that was imploding because of poor governance systems. Here I am now, and I feel as if I’m in the same story that’s been going on for 20 years.’

86 words. So let’s say one minute of talking time. Maybe two.

What did I say? I said, in essence, you can trust me. I might not be a communications expert, but I really am familiar with the territory you are in and the challenges you face, because I’ve been there. So I can be helpful to you. I’d say it took me the best part of three hours to arrive at those 86 words!

Sometimes the Who Am I story might be offered to reassure. For example in a recent piece of research about transformation programmes, one interviewee spoke of the need to restructure the business and the importance, in delivering this message, of being able to stand there and say

‘We, the leadership team, are experienced. I’ve done this before. It ain’t easy, but I know what I’m doing, and you’re in safe hands, even if we have to make tough decisions.’

That’s a Who Am I story. Small, delicate, carefully judged reassurance that allows the listener to see and relate to the teller.

This is the kind of thing that Doug Lipman is so good at coaching people at. Try his story in a box, if personal storytelling skills is something you want to develop.

*small stories that say a lot*

Finally we have arrived at the telling part and are back to Svend-Erik’s pebbles.

What kind of stories are you telling?

I’d suggest you aim mostly for small, serviceable moments that you can collect swiftly and easily, share lightly that will go quite deep and open up new spaces for the listener and between you and the listener.

a gate in the fence

I’m reminded of a small firm of female architects I met years ago who’d describe the distinctive qualities of their firm along these lines:

‘We were doing a project for a primary school recently, who wanted to create a closer link between the building they had and the building next door that they’d just bought to enlarge their reception intake. We looked at all kinds of structural solutions, and in the end we recommended a gate in the fence that ran between the two gardens.’

In the smallest, most miniature sketch, a whole picture is painted of the values of the firm and what they stand for.

It’s these kind of miniatures that you’re equipping yourself with. Perhaps it helps to imagine these as small pebbles that you can throw into a conversation, whose effect can ripple outwards.

Who can tell the shortest story? Stuck in a pub, this story won a bet for Ernest Hemingway:

‘For sale. Baby shoes. Never worn.’

It’s become a kind of cult with competitions happening quite regularly to find a story in six words.

from bat droppings to getting bums on seats

Natural England found just this when they recently created a management and staff briefing session about the story of knowledge at Natural England. They wanted to find conversation-starting anecdotes that would illustrate different aspects of knowledge Natural England people use to get the job done. A handful of people kept ‘decision journals’ for a week, then picked one decision that had been particularly tricky, to describe in a bit more detail.

Nine or so typical circumstances were turned into tiny tales – one- or two minute conversation starters. They ranged from detailed knowledge about bat dropping which affected the timing on plans for disabled parking at a local wildlife trust to figuring out how to get the right-sized chairs into a parish hall just ahead of a meeting about a parish plan (and in so doing drawing on a previous life as a roadie).

The bigger story that these nine tales tell is that the knowledge it takes to put Natural England into a role of active advocacy ranges from individual, professional expertise and operational experience to personal confidence in handling networks, to being able to hold a line in a tricky and emotional situation. That’s an easier story to hear, and see your part in as a member of staff, if you can see it through the kaleidoscope lens of a series of small vignettes.

decisions & dilemmas

A footnote on method here. We used a tool we call decision journals to prompt people to recall decisions they made, and reflect on them. We thought that tricky decisions would, naturally, lead to an interesting range of knowledge and expertise that told a good story, where asking questions about knowledge would have been a bit more obscure.

This is a pretty good test of where a good story might lie too – where’ve you been stuck a bit, and what you did to get unstuck is normally a good starting point for digging about for the story behind the stuckness`.

Both these ways of asking questions also provide a human scale of telling which helps with retelling. In more elaborate settings, Gary Klein’s critical decision method probes the same kind of territory, but do you also need to balance your collecting with what you plan to do with the collection, and try and size things so that you are neither stretching thin material too far or squashing intricate stories into forms that they burst out of.

an old tea caddy

A small object is another way to tell a big story too, sometimes a very moving one. At a workshop a few years back we were exploring the role of archives in today’s business innovation and knowledge transfer, the John Lewis archivist bought a series of objects from their archive. One in particular is a battered old metal tea caddy with coins fused to the base. It was the staff tea money collection box and was retrieved from the bombed ruins of the store in the 1940s.

It’s used today to convey to staff the message

‘Look, we were bombed to rubble only 60 years ago. And look at John Lewis today. If we can survive that, we can survive this credit crunch.’

To help you start this process, and order your thoughts and noticings, we’ve attached a story sheet at thee end which can help you catalogue some of the more essential small stories that you find yourself collecting and wanting to use.

surprise and insignificant details

A couple of things can really help with organisational stories that tend towards the dull and predictable:

Something people didn’t see coming – this could be in the way you reveal the story, or parts of it, including your own reactions, or it could be in the unintended consequences.

Insignificant details (a striking image, colour, texture, a smell, a small object that plays a role), give the listener something to hook onto that help them carry the story with them. (Appreciative Enquiry is big on insignificant details, and they’re a great social connector too, if the question is posed in groups in a workshop as the details become, in turn, a kind of mnemonic for remembering stories and the people who told them.)

‘We were helping the islands build new roads, and of course they helped speed up vegetables to market and so on. What we didn’t expect when we started was to be providing young ex-offenders with a way back into the workplace through highway maintenance.’

(There’s a danger here to watch out for: what might seem surprising to you is something I’m already very familiar with. So, from the same sector. I might think that the leapfrogging of telephony over other technologies in Afghanistan and the power it gives to women, or to children to learn, or to people do to their banking, is interesting, but to everyone in the developing world, it’s normal and I look silly making too much of it.)

finding a practice partner

You’ll need to be vigilant at this point and most probably you’ll need to cast around for help from someone who can help you surgically remove all reportwriting and organisational jargon. As you’re acclimatized to it, it’s a lot harder than you think for you to do this alone. Find someone to sit down with and fumble your way through the first couple of tellings.

Here’s a set of instructions you can give them, adapted again from Svend-Erik Engh that the invited listener can use to provide feedback.

Thank the teller for telling the story.

Say something nice about the way it was told.

Tell the teller of the clearest picture in the story: your strongest image or memory left after listening to the story.

Comment on what have you’ve heard and understood from the story.

Ask if the response was useful and so invite the teller’s feedback on your feedback.

Appreciation of a story can be global: ‘I love the way you tell the story.’

Or it can be specific: ‘I really liked the moment when she opened the restaurant.’ ‘I could smell the mangos at the roadside.’

BRIO

Doug Lipman, who has great tips and hints to offer for becoming a confident and easy teller, also has a very neat trick for helping remember stories and having them readily to hand. He calls this BRIO: Brief Recollection of Image Order. Of course it’s nothing more than sequencing the order in which you want to retell a story with a mnemonic series of images, but it’s a neat trick and one worth remembering for more formal occasions.

sliding anecdotes into place

At this point you need to throw away every last scrap of the residue of that last communications training day (tell them what you’re going to tell them, tell them, then tell them what you’ve told them). No. Just don’t.

Firstly you need to even think about whether to signal to people that you know you’re telling a story. It might be right.

‘Let me give you an example so that you can get a feel for it’.

But how much more interesting to creep up on them and surprise them:

‘You know, coming here, I ran over a fox, and that suddenly got me thinking about how vulnerable we all are to being hit by something we didn’t see coming…’

‘I wonder if you all remember that time a few years back when x did y…’

‘That brings to mind a meeting we were having the other day. Maybe it’s worth me taking a few minutes to tell you what happened there.’

I do find that being studiedly inconsequential is very useful on most occasions.

It appears not to place too heavy a demand on your listener, inviting them to come to what you’re offering in their own time and way.

Above all, you need to be yourself and you need to tell stories that have meaning for you. If it doesn’t mean anything to you, why are you telling it?

And why should it matter to the person you are telling it to?

the traces of the storyteller

Of course, there are situations in which you need to craft something a bit sturdier, longer, more studied, that will command attention. These are the kinds of stories you can craft over time as your distinctive practice takes shape.

And for this, it’s useful to end by going back to Walter Benjamin: ‘The storytelling that thrives for a long time in the milieu of work – the rural, the maritime, and the urban – is itself an artisan form of communication, as it were. It does not aim to convey the pure essence of the thing, like information, or a report. It sinks the thing into the life of the storyteller, in order to bring it out of him again. Thus traces of the storyteller cling to the story the way the handprints of the potter cling to the clay vessel.’

You don’t need to wear the hard work on the outside. The more the story appears to have arrived, as if by chance, in an unsignalled way, the less you’re instructing people to react in a particular way and inviting them to choose to see and hear you and encounter you differently.

‘Why,’ said the Dodo, ‘the best way to explain it is to do it.’ Lewis Carroll.

further reading, listening and watching

Shawn Callahan and Mark Schenk at Anecdote in Australia have a very practical and engaging website, bursting with useful resources.

Annette Simmons who founded Group Process Consulting in the 1980’s as written two handy books and her website has useful resources on it too.

‘Building bridge using narrative techniques’ has lots of useful techniques and can be downloaded from the publications in the story section here

‘Using story to carve out spaces in which the organisation can start to breathe’ by Victoria Ward, from an edition of AI practitioner edited by Natalie Shell in February 2008. is also available here

Smart Meme has some useful resources and worksheets for campaigning and activist organisations, of which ‘The Battle of the Stories’ is a particularly useful one.

Doug Lipman is an experienced storyteller and teacher who has plenty o

pragmatic tips and ideas to offer.

Sharing the stories of the Cairngorms National Park – a guide to interpreting the area’s distinct character and coherent identity. This is a great guide, whose principles can be applied in other settings

‘The Storyteller’ by Walter Benjamin was written between the wars. It’s the best single thing I’ve ever read about storytelling.

And three useful books of theoretical context:

Ken Gergen ‘An invitation to social construction’ (Sage Publications 1999)

Lewis Hyde ‘The Gift’ (Vintage Books, 1983)

Karl Weick, ‘Sense making in Organisations’ (Sage Publications 1992)

Four places to go to spring the imagination:

David Lynch’s Interview project is good fuel for the imagination about how to make room for the ordinary to become extraordinary.

‘Geldof in Africa’ 8 Audio CD boxset published by the BBC, reference, BBC71850, is a tour de forceof storytelling (whether you care for Geldof or not, which I don’t)

‘Stuart: a life backwards’ by Alexander Masters, is structurally interesting for the way it weaves the forward journey of the author with the reverse journey of his subject, makes a predictable story surprising and demanding and carries the reader through a complex large story too.

The incidental is a multi-disciplinary network founded by sound artist David Gunn which plays with soundscapes and storytelling in challenging new ways.

story sheet

catchy name

main time and place of events

this is about a time when…(one sentence)

themes and keywords

main emotion

notes about how you could use

this story

what happened

texture and detail that will help you craft the story

for the record: any other people, materials, evidence or stories that could tell you more

fieldnotes on what has happened when you’ve tried to retell the story in different settings

#Bob Geldof#Doug Lipman#Max Boisot#Annette Simmons#Madelyn Blair#Shawn Callahan#Mark Shenk#Alexander Masters#Ken Gergen#David Lunch#Lewis Hyde#Karl Weick#Cairngorms National Park Authoraity#John Lewis#Appreciative Inquiry#Natalie Shell#Svend-Erick Engh#Walter Benjamin#Lewis Carroll#Natural England#Ernest Hemingway#Jonathan Miller#Hewlitt-Packard#Greg Dykes#York University#David Bohm

0 notes

Text

ESADE commemoration of Max BOISOT on Dec 1st

Just flying back from Asia, I was in Barcelona last Thursday to attend to the commemoration of Max BOISOT organized by ESADE.

I repost here the message posted by Dave Snowdon on his blog Cognitive Edge.

I flew into Barcelona yesterday on the final leg of an overlong trip. The reason was to attend a gathering in memory of Max Boisot organised by ESADE at the Universidad Ramon Llull where Max taught for many years. Eugenia Bieto, Jonathan Wareham and Conxita Folguera deserve much praise for organising it, and for their words at the event. Otherwise we had the three old me of myself, J C Spender and Bill McKelvey talking of his contribution to the field of knowledge and our personal experiences of working with him. Agustí Canals and Sabrina Moreira who had been his PhD students gave particularly moving tributes.

I focused on using the words from Max's blog as a focusing device and thanks to Les Hales (in the picture with Max and myself) prompt response to an email was able to share some pictures of Max at the Hong Kong Sevens last year. We only got him to come by arguing that it would provide a source of anthropological study. Once there he threw himself into the spirit of the thing as can be seen from the picture below. The requiem mass had been a solemn affair and I broke down when speaking. This was more of a celebration, a memory of happy times; but the sense of loss is still there.

Dave's words perfectly picture the celebration of Max.

It was nice meeting with Max's family and with colleagues whom we most often only "meet" via email.

Together we remembered happy times with Max, either at conferences or when discussing research papers together. We also discussed with Bill and Agusti how difficult it is to now carry on the projects started with Max over the last years. We all have now to complete research papers coauthored with Max, and we face the same tremendous difficulty: we used to have challenging interactions about all these topics and we progressed during exhausting discussions with Max. And we enjoyed it as much as Max did himself.

0 notes

Text

Tweeted

Max Boisot has argued that there are two different strategies in #complexity #governance: complexity reduction & absorption. ”Funelling” seems to represent the first strategy and ”Layering” the second. We may need to combine them with wicked problems. #sitralab pic.twitter.com/gE6bKuSdkb

— Timo Hämäläinen (@HmlinenTimo) January 27, 2020

0 notes

Text

A gathering in memory of Max Boisot, at ESADE on DEC 01, 2011

My friend and colleague Max Boisot passed away last September. One of his last positions was a visiting professorship with ESADE in Barcelona (Spain). ESADE is organizing tomorrow a gathering in his memory.

Gathering in Memory of Max Boisot

Speakers:

Eugenia Bieto, Director General, ESADE

Alfons Sauquet, Dean, ESADE Business School

Jonathan Wareham, Vice-Dean for Research, ESADE Business School

Conxita Folguera, Professor and Director, Department of People Management and Organisation, ESADE

JC Spender, Visiting Professor, Department of People Management and Organisation, ESADE

Bill McKelvey, University of California, Los Angeles

Dave Snowden, Cognitive Edge Pte, Ltd

Sabrina Moreira, PhD candidate, studied under Max Boisot

Agustí Canals, the UOC professor and former student of Max Boisot

The event will be held in English.

Further information and registration here

Venue ESADEFORUM Av. Pedralbes, 60-62 Barcelona

For further information: Public Relations · Fina Planas · 934 952 064 · 932 806 162, ext. 2410 email: [email protected]

2 notes

·

View notes